Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Humor 2019 0081

Uploaded by

Ariq RamadhanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Humor 2019 0081

Uploaded by

Ariq RamadhanCopyright:

Available Formats

Humor 2020; 20190081

Book Review

A unified theory of irony? As if ! Irony, by Joana Garmendia

Reviewed by Tony Veale, Computer Science, UCD, Belfield, Dublin D4 D4, Dublin, Ireland,

E-mail: Tony.veale@UCD.ie

https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2019-0081

Goethe’s observation that “words come in handy when ideas fail us” has

rarely found a more apt target than our understanding of irony. Modern

discourse is steeped in it, to the extent that we often feel the need to break

its cardinal rule when speaking ironically on social media: we actually

announce our ironic intent with the hashtag #irony, both to make our ironies

stand out above others and to avoid the backlash of internet shaming when

our intent is misunderstood. When we look at the observations that merit this

tag, we find as many views on what it means to be ironic as we find speakers

declaring themselves to be ironic. That the tag is equally at home in tweets

that exhibit verbal, situational, dramatic and poetic irony at least suggests

that there is something shared by these various forms that is deserving of a

common label. Yet what seems to unite these uses is the belief that irony can

be anything one wants it to be, provided we can discern both humour and

aptness in an act, an utterance or a situation. Thus, a guide to Mumbai thinks

it ironic that a nightclub that was one frequented by gangsters is now an

Italian restaurant named “Corleone”, while a famous singer has built her

career on a song that sees irony lurking behind life’s unwanted coincidences,

just as at least one comedian has built his on a witty analysis of what she gets

wrong. Our folk notions of irony are so remarkably elastic that they are

stretchy enough to accommodate everything from comic coincidence to logi-

cal contradiction and self-serving hypocrisy. Our formal accounts may do a

better job of identifying the most diagnostic features of irony, but they are no

less stretchy for being formal.

This crowded Venn diagram of scholarly perspectives is excellently sur-

veyed in a new book from Joana Garmendia, simply titled Irony, as part of the

series Key Topics in Semantics and Pragmatics from Cambridge University

Press. Her book is concise but satisfyingly comprehensive, and shines its

spotlight fairly on the many arguments and counter-arguments that compete

for our attention in the literature. Having placed irony in its proper rhetorical

context, and teased apart the various strands that the word weaves together as

one, Garmendia settles on verbal irony, and considers the relative strengths

and weaknesses of the three major families of formal accounts: those grounded

Brought to you by | Utrecht University Library

Authenticated

Download Date | 3/9/20 7:10 AM

2 Book Review

in opposition, those grounded in echoes, and those grounded in pretence.

Although Garmendia is a neo-Gricean who finds much that is worth preserving

in the views of the éminence Grice, she does not shy away from their short-

comings. That the grand old cheese is full of holes and melts easily under the

heat of scrutiny will surprise no-one – hence the diversity of contemporary

scholarly views on irony – but the holes at least allow his implicature account

to be enriched with additional nuances and perspectives. So among the qual-

ities worth salvaging we find: ironic utterances must do more than simply

imply the opposite of what they say – there must be communicative value in

the opposition too; irony always carries a tinge of criticism, even when it seems

to be used for positive ends; irony involves a pretence that asks listeners to

collude in the construction of meaning; and though ironic statements are often

said in a seemingly arch manner, there is no distinctively ironic tone of voice.

In her own revision of, and departure from Grice, Garmendia offers an “as-if”

theory of irony that retains its reliance on implicature as well as its critical

bent. Since Grice himself noted (but left under-developed) the role of pretence,

her view that ironic speakers communicate one stance as if communicating

another allows her to naturally integrate important elements of the pretence

and echoic views too.

These echoic and pretence views are explored with equal depth in chapters

of their own, showing where these stances differ and agree, either with them-

selves or with Grice. Sperber and Wilson’s theory of the ironic echo is perhaps

the more formidable and specific of the two, although their notion of what

constitutes an echo has necessarily been stretched and reshaped over the

years to account for ever more nuanced challenges from rival theories. At its

simplest, the ironic echo is a means of mocking an assertion or a prediction by

repeating it in a falsifying context, as when we utter “lovely day for a picnic” on

a rain-sodden afternoon. But echoes don’t have to literally echo, or even para-

phrase, a past utterance; they can capture the naïveté of a prediction that has

failed to materialize, such as the act of scheduling a get-together as a picnic in

the first place, or merely echo the presumed state of mind or world view of the

addressee. We can even stretch the notion of an echo to explain the naming of

that Mumbai restaurant as an ironic speech act; by calling the establishment

“Corleone,” the new owners seem to be echoing its former status as a hive of

villainy, and winking at those in the know.

The echoic account hinges on the distinction between use and mention, for

to ironically echo a proposition is not to use it as is but as if. To knowingly

echo but not actually use another’s propositions (real or attributed) requires a

suspension of disbelief, perhaps marked by a wink, a nod, an arch tone or a

pair of air quotes. Just as a good lie contains more than a grain of truth, an

Brought to you by | Utrecht University Library

Authenticated

Download Date | 3/9/20 7:10 AM

Book Review 3

effective pretence will borrow from, or echo, that which it seeks to ridicule. So

disentangling the echoic account of Sperber & Wilson from the pretence

theories of Clark & Gerrig and of others requires some close reading, but

Garmendia is equal to the task. Whether echo is seen as a tool of pretence,

or whether pretence is a prerequisite for echo, it is clear that each view has

amassed its own stronghold of supporting examples. The discussion leads,

inexorably, not to a victory of one account over another but to the realization

that irony is a polythetic concept whose many forms are linked by a series of

family resemblances rather than by any clearly defined essence. In the context

of utterances that wink at an audience, irony looks just like pretence, but in the

context of utterances that remind us of failed predictions, it looks just like an

echoic allusion. In between these poles we find a world of examples that can

be made, with just a little ingenuity, to look like one or the other. Garmendia

doesn’t pick sides or pick fights, but shows us that – like the users of #irony on

Twitter – we can treat these alternate views as a buffet rather than a set meal.

Irony’s history of scholarly disputes is the stuff of propulsive narrative,

and in Garmendia’s concise telling this history often feels like a blow-by-blow

report of a boxing match on the radio: as each punch from one corner invites a

counter-punch from another, the effect is almost just as thrilling. She develops

her talking points logically, prompting readers to think loud “buts” at key

junctures before then voicing many of the same objections. But a compact

volume such as this can only cover so much, and it is worth mentioning some

of the topics that get less than a full treatment. For instance, just what is the

exact relationship of sarcasm to irony? Despite their evident family resem-

blance, scholars often feel the need to stipulate a certain relation from the

outset. Is sarcasm just a more savage form of irony, one that sacrifices plau-

sible deniability for a biting, unambiguous scorn, or is irony a more subtle and

emotionally-muted form of sarcasm? Twitter users disprove (or at least chal-

lenge) Grice’s claim that irony is a pretence that cannot be overtly marked as

such without ceasing to be irony, but what other, less overt markers of play-

fulness do speakers use to facilitate ironic communication? Are there linguistic

constructions for irony and sarcasm, or are some instances more formulaic

than others, or indeed, is sarcasm more formulaic than irony? What is the link

between irony and humour? Does irony always strive for humour, or does it

simply share the latter’s use for incongruities that paint a bigger picture? To

her credit, these questions and more are addressed in Garmendia’s book, if not

in the same depth or breadth as more central concerns. For all that, she does

not stint on her approach to evergreen questions in the irony literature, such as

whether irony always criticizes, even in its positive form when it seems

intended to praise, or whether the notion of an ironic tone of voice is at all

Brought to you by | Utrecht University Library

Authenticated

Download Date | 3/9/20 7:10 AM

4 Book Review

credible. These are questions to which Garmendia returns throughout her

book, and to which she offers credible answers. As a compact guide to a

complex and contentious topic, readers will find little to quibble about in

Garmendia’s engaging treatment. This is a book that will earn its keep on

your shelf, to come in handy when words and ideas fail you. Perhaps you’ll

keep it for a rainy day. Picnics are so overrated.

Brought to you by | Utrecht University Library

Authenticated

Download Date | 3/9/20 7:10 AM

You might also like

- An Essay on Laughter: Its Forms, Its Causes, Its Development and Its ValueFrom EverandAn Essay on Laughter: Its Forms, Its Causes, Its Development and Its ValueNo ratings yet

- Brondino-Irony, Relevance, and Eco (2023)Document18 pagesBrondino-Irony, Relevance, and Eco (2023)jbpicadoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 152.37.94.109 On Wed, 11 May 2022 20:20:24 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 152.37.94.109 On Wed, 11 May 2022 20:20:24 UTC陈义No ratings yet

- New Realist ReadingsDocument29 pagesNew Realist ReadingsJames HerringNo ratings yet

- NYONGO - Opacity, Narration, and "The Fathomless Word"Document12 pagesNYONGO - Opacity, Narration, and "The Fathomless Word"Bruno De Orleans Bragança ReisNo ratings yet

- Rita Felski: After SuspicionDocument8 pagesRita Felski: After SuspicionChiara Zwicky SarkozyNo ratings yet

- 21 Brief ResponseDocument6 pages21 Brief ResponseweareyedNo ratings yet

- Straight and Crooked ThinkingDocument127 pagesStraight and Crooked ThinkingWajiha KhanNo ratings yet

- Henri Bergson: Collected Works: Laughter, Time and Free Will, Creative Evolution, Matter and Memory, Meaning of the War & DreamsFrom EverandHenri Bergson: Collected Works: Laughter, Time and Free Will, Creative Evolution, Matter and Memory, Meaning of the War & DreamsNo ratings yet

- With Continual Reference To Rodney Graham: Towards An Art of IronyDocument38 pagesWith Continual Reference To Rodney Graham: Towards An Art of IronyMaxwell G GrahamNo ratings yet

- Felski Suspicion 2009Document9 pagesFelski Suspicion 2009Jason KingNo ratings yet

- Intratextual Irony in AristophanesDocument26 pagesIntratextual Irony in AristophanesAnonymous OpjcJ3No ratings yet

- Isntitironic PDFDocument22 pagesIsntitironic PDFKarin RebazaNo ratings yet

- Isntitironic PDFDocument22 pagesIsntitironic PDFKarin RebazaNo ratings yet

- Straight and Crooked ThinkingDocument127 pagesStraight and Crooked Thinkingy9835679100% (2)

- Zumthor ParadoxesDocument13 pagesZumthor ParadoxesSarah MassoniNo ratings yet

- Ambiguous Storytelling in Three Texts: Unsettling The Perception of RealityDocument22 pagesAmbiguous Storytelling in Three Texts: Unsettling The Perception of RealityLUZAR Santiago-NicolasNo ratings yet

- Copy Left DI Gest: Vol. O0IDocument27 pagesCopy Left DI Gest: Vol. O0IChristian GreerNo ratings yet

- Two Comments On Textual Harassment of Marvell's Coy Mistress The InstitutionalizationDocument7 pagesTwo Comments On Textual Harassment of Marvell's Coy Mistress The InstitutionalizationVilian MangueiraNo ratings yet

- Fine Comedy in The 'Iliad'Document23 pagesFine Comedy in The 'Iliad'HollyNo ratings yet

- Rice UniversityDocument13 pagesRice UniversityJARJARIANo ratings yet

- GENRE GAMES: EDWARD GOREY'S PLAY WITH FORMDocument216 pagesGENRE GAMES: EDWARD GOREY'S PLAY WITH FORMAngelica Micoanski ThomazineNo ratings yet

- AnatomyDocument314 pagesAnatomyGiannis Diego Kalogiannis100% (5)

- What Is Close ReadingDocument5 pagesWhat Is Close ReadingGia Huong HoangNo ratings yet

- Giorgio Agamben Friendship 1 PDFDocument6 pagesGiorgio Agamben Friendship 1 PDFcamilobeNo ratings yet

- Download Weird Fiction A Genre Study Michael Cisco all chapterDocument67 pagesDownload Weird Fiction A Genre Study Michael Cisco all chapterjanice.faupel319100% (12)

- On The Classification of IroniesDocument11 pagesOn The Classification of IroniesGeronto SpoërriNo ratings yet

- The Progress of The Intellect, As Ememplified in The Religious Development of The Greeks and Hebrews, Vol. 1, Robert Mackay. (1850)Document512 pagesThe Progress of The Intellect, As Ememplified in The Religious Development of The Greeks and Hebrews, Vol. 1, Robert Mackay. (1850)David BaileyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Irony in FilmDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Irony in FilmJames MacDowellNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric and Bullshit PDFDocument17 pagesRhetoric and Bullshit PDFEricPezoa100% (1)

- Middling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyFrom EverandMiddling Romanticism: Reading in the Gaps, from Kant to AshberyNo ratings yet

- Multiverse Role Playing Games As An EducDocument4 pagesMultiverse Role Playing Games As An EducCarlo Robles MelgarejoNo ratings yet

- Types of IronyDocument7 pagesTypes of IronyЕкатерина МитюковаNo ratings yet

- Steve Helmling - 'Immanent Critique' and 'Dialetical Mimesis' in Adorno & Horkheimer's Dialectic of EnlightenmentDocument21 pagesSteve Helmling - 'Immanent Critique' and 'Dialetical Mimesis' in Adorno & Horkheimer's Dialectic of EnlightenmentBenito Eduardo MaesoNo ratings yet

- Literary Essays on Convergence and DivergenceDocument34 pagesLiterary Essays on Convergence and DivergenceReina Krizel AdrianoNo ratings yet

- Can a Robot be Human?: 33 Perplexing Philosophy PuzzlesFrom EverandCan a Robot be Human?: 33 Perplexing Philosophy PuzzlesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (17)

- The Irony of SocratesDocument13 pagesThe Irony of SocratesAngela Marcela López RendónNo ratings yet

- Scan 0003Document1 pageScan 0003api-244172059No ratings yet

- Agamben FriendshipDocument6 pagesAgamben FriendshippomahskyNo ratings yet

- Forensic, Political and Epideictic Discourse TypesDocument31 pagesForensic, Political and Epideictic Discourse TypesXin ZhaoNo ratings yet

- Coke Vs Pepsi EssayDocument4 pagesCoke Vs Pepsi Essayidmcgzbaf100% (2)

- David Ives Time Flies and As ParodyDocument8 pagesDavid Ives Time Flies and As Parodyaynaz shNo ratings yet

- Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic: An Essay on the Meaning of the ComicFrom EverandLaughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic: An Essay on the Meaning of the ComicNo ratings yet

- Unit8 Narration in Fiction and Third World Preferences: StuctureDocument9 pagesUnit8 Narration in Fiction and Third World Preferences: StuctureIyengar SSNo ratings yet

- Essay About New York CityDocument7 pagesEssay About New York Cityafabittrf100% (2)

- Ronna Burger Platos Phaedrus A Defense of A Philosophic Art of Writing 1980 PDFDocument168 pagesRonna Burger Platos Phaedrus A Defense of A Philosophic Art of Writing 1980 PDFolvidosinopuestoNo ratings yet

- Irony as a Principle of Structure in PoetryDocument4 pagesIrony as a Principle of Structure in Poetryruttiger57No ratings yet

- Perfidious Fidelity. The Untranslatability of The OtherDocument11 pagesPerfidious Fidelity. The Untranslatability of The OtherSanjukta SunderasonNo ratings yet

- Plato and The Spectacle of LaughterDocument15 pagesPlato and The Spectacle of LaughterSan José Río HondoNo ratings yet

- Laughter (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): An Essay on the Meaning of the ComicFrom EverandLaughter (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): An Essay on the Meaning of the ComicNo ratings yet

- Language and Social ClassDocument9 pagesLanguage and Social ClassFady Ezzat 1No ratings yet

- Bal Bhavan Public Syllabus Class XI EnglishDocument5 pagesBal Bhavan Public Syllabus Class XI EnglishSumit UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Prepositions Explained: Important Notes on UsageDocument7 pagesPrepositions Explained: Important Notes on UsageMilanNo ratings yet

- Summary WritingDocument2 pagesSummary WritingNuhaaNo ratings yet

- 19497-Article Text-37985-1-10-20171129Document5 pages19497-Article Text-37985-1-10-20171129Muhammad RamadhanNo ratings yet

- UbikeDocument10 pagesUbikepeipei20230129No ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument2 pagesAssignmentSyeda AleenaNo ratings yet

- 45th Super Exam BatchDocument8 pages45th Super Exam Batchmd polash hossainNo ratings yet

- Sf1 - 2022 - Grade 7 (Year I) - SunflowerDocument8 pagesSf1 - 2022 - Grade 7 (Year I) - SunflowerDaiseree SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Speech For Basic Level JapaneseDocument168 pagesSpeech For Basic Level JapaneseRiset-chan100% (2)

- Lecture-2 Language Across Curriculum 4-A PDFDocument5 pagesLecture-2 Language Across Curriculum 4-A PDFVanishaNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint PresentationDocument10 pagesPowerpoint PresentationJamilNo ratings yet

- Theory of TranslationDocument33 pagesTheory of TranslationmirzasoeNo ratings yet

- Colloquial TurkishDocument382 pagesColloquial TurkishDoina Pdp94% (18)

- Interpersonal Communication and You An Introduction (Steven McCornack)Document340 pagesInterpersonal Communication and You An Introduction (Steven McCornack)mohammed Maktoum100% (2)

- How To Learn ArabicDocument4 pagesHow To Learn ArabicTomNo ratings yet

- Pulse2 Teachersbook U6Document26 pagesPulse2 Teachersbook U6Fräulein Faridah50% (2)

- Lesson 1Document23 pagesLesson 1Cherry LimNo ratings yet

- Redesign and Redo of LinkedinDocument6 pagesRedesign and Redo of Linkedinprabhjot2k23No ratings yet

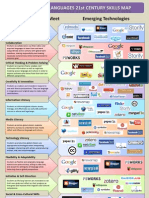

- ACTFL 21St Century Skills Meet Technology InfographicDocument1 pageACTFL 21St Century Skills Meet Technology InfographicSusan Murray-CarricoNo ratings yet

- Week 4-Mood of The VerbsDocument16 pagesWeek 4-Mood of The VerbsjustKThingsNo ratings yet

- Where's Mum ES1Document23 pagesWhere's Mum ES1S TANCREDNo ratings yet

- Snot Stew Literature CircleDocument2 pagesSnot Stew Literature Circleapi-338531822No ratings yet

- Rules and Guidelines: FOR Primary and Secondary SchoolsDocument12 pagesRules and Guidelines: FOR Primary and Secondary Schoolskhairul izzuddinNo ratings yet

- Connotative vs Denotative Meanings GuideDocument2 pagesConnotative vs Denotative Meanings GuideTivar VictorNo ratings yet

- New Sky 2 - TEACHERS Book OCR PDFDocument146 pagesNew Sky 2 - TEACHERS Book OCR PDFJasminka Trajkovska75% (8)

- Geriatric Unit MMSE Administration GuideDocument2 pagesGeriatric Unit MMSE Administration GuidelilydariniNo ratings yet

- Assessing Intercultural Capability in Learning LanguagesDocument7 pagesAssessing Intercultural Capability in Learning Languagesgülay doğruNo ratings yet

- ALS Writing RubricDocument2 pagesALS Writing RubricJAYPEE ATURONo ratings yet

- Module #6 Javeria Khatoon D14785: Concept of The Sky LettersDocument16 pagesModule #6 Javeria Khatoon D14785: Concept of The Sky Lettersjaveria khatoonNo ratings yet