Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nurse Protocol Article

Nurse Protocol Article

Uploaded by

Mohamed Abd El MonemCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nurse Protocol Article

Nurse Protocol Article

Uploaded by

Mohamed Abd El MonemCopyright:

Available Formats

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti...

for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke: the development of a

nurse protocol in the United Kingdom

IST-3 Stroke Nurse Collaborative Group (see appendix for list of collaborators and

participating hospitals)

Abstract

This paper describes a nursing protocol for patients treated with thrombolysis for acute

ischaemic stroke developed during the Stroke Association phase of the Third International

Stroke Trial (IST-3), a randomised controlled trial of recombinant tissue plasminogen

activator for acute ischaemic stoke.

The IST-3 Nurse collaborative group met three times over three years. The meetings consisted

of educational updates on stroke thrombolysis, training on trial procedures, presentations by

participating nurses and discussions of good practice, local initiatives and sharing common

problems.

Lack of knowledge, fear of bleeding complications and lack of appropriate NHS beds were

common barriers. Core nursing requirements suggested by this research included:

fast-tracking of patients; access to trained stroke physicians; acute physiological monitoring

and nursing intervention; effective communication and support of patients and carers;

knowledge of complications and actions to be taken; transfer to an appropriately skilled stroke

unit environment and successful discharge planning to home or rehabilitation.

INTRODUCTION

This article summarises the reasons why thrombolytic therapy is a promising treatment for

acute ischaemic stroke and describes the development of the core nursing implications of

introducing thrombolytic therapy in selected United Kingdom hospitals. In 2002, the Committee

for Proprietary Medicinal Products for the European Union, agreed a framework to allow

national drug licensing bodies of individual European Union countries to grant a licence for

alteplase (a recombinant tissue plasminogen activator thrombolytic agent known as rt-PA). This

may lead to a license being granted in the UK for patients treated up to three hours following an

ischaemic stroke (at the time of writing this was still awaited). Consequently, there is an urgent

need to establish and refine appropriate nursing guidelines for NHS hospitals.

Stroke is a major problem in the United Kingdom

In the UK, about 150,000 people have a stroke each year (110,000 being first-ever strokes)

(Bamford et al, 1988). The underlying pathology in 85% of patients with stroke is cerebral

ischaemia (infarction), and therefore treatments directed at this subgroup will have greatest

impact (Bamford et al, 1990). Stroke is an important illness, as 30% of patients are dead within

6 months and a further 30% are dependent in activities of living. (Bamford et al, 1990). In

addition, stroke consumes about 5% of all NHS resources and places a considerable burden on

family and carers. (Isard and Forbes, 1992; Department of Health (DOH), 2001). It remains a

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (1 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

major health problem for Europe, with a stroke rate of about 1 million a year, and globally, with

over 5 million stroke deaths around the world. (Sandercock et al, 1992).

As the population ages, stroke is likely to become more frequent even if stroke incidence rates

remain constant or decline. It is, therefore, likely that stroke will represent a significant health

problem for many decades to come. Important research investment in stroke is needed to

tackle this problem. There needs to be effective stroke prevention and improvement in stroke

management through greater availability of stroke units to provide acute treatment and

rehabilitation and facilitate research. (DOH, 2001; Rothwell 2001)

Better treatments needed for acute stroke

Few treatments are effective for acute stroke. Aspirin treatment (150-300mg daily, orally or

rectally, started immediately after acute ischaemic stroke confirmed) has only modest benefit

(approximately 12 more independent survivors per 1,000 treated).(Chen et al, 2000) In

contrast, thrombolytic therapy, which works by dissolving the thrombus causing the ischaemic

stroke, can potentially re-open the occluded artery and reverse the stroke. Research has

demonstrated that some patients with severely disabling stroke (e.g. aphasia, dense

hemiparesis and hemianopia) recover quickly after emergency with thrombolysis, and are

discharged home within days, with little or no residual disability. (The National Institute of

Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group 1995) Without effective treatment,

such patients usually require months of in-patient rehabilitation, have a high risk of dying and

often need long-term institutional care. (Stroke Unit Trialists' 2001)

Why is thrombolytic therapy the promising treatment to evaluate for acute ischaemic

stroke?

There have now been 18 completed randomised controlled trials involving 5721 patients, of

thrombolytic therapy for acute ischaemic stroke and the results from these trials have been

systematically reviewed in the Cochrane Library. (Wardlaw et al. 2003) This Library provides

high quality systematic reviews of medical treatment (and management strategies) and is

widely available in medical libraries and the Internet (http://www.update-software.com/cochrane).

Table 5 lists references for the trials.

Four different thrombolytic agents have been evaluated but about half of the data come from

trials of alteplase (recombinant tissue plasminogen activator or rt-PA for short). Sixteen trials

used the intravenous route of administration, with only two using the more complex intra-arterial

route. The time window from onset of stroke symptoms to treatment varied between trials but

almost all patients were treated within six hours of the onset of stroke symptoms.

In the following sections the overall results of thrombolytic therapy from the systematic review

are summarised.

RESULTS OF THROMBOLYTIC THERAPY

Reduction in "death or dependency".

Thrombolytic treatment significantly reduced the number of patients dead or dependent from

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (2 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

58% in control patients to 53.3% in treated patients. (Wardlaw et al, 2003) This is equivalent to

an additional 43 independent survivors for every 100 patients treated (95% Confidence Interval

13 to 71). This is a substantial and worthwhile benefit.

Risk of major intracranial haemorrhage.

The main risk of thrombolytic therapy for stroke is fatal intracranial haemorrhage (ICH). The

data in the Cochrane review showed that treatment increased the absolute risk of fatal ICH

from 0.9% in control patients to 5.1% in treated patients (2p<0.00001, a highly significant

result). The risk of symptomatic ICH (including fatal bleeds) increased from about 2.3% to 8.7%

(2p<0.00001).(Wardlaw, de Zoppo, Yamaguchi, & Berge2003)

The risks of alteplase were somewhat less and the benefits somewhat more and thus alteplase

appears to be one of the more promising thrombolytic agents to evaluate in further trials.

(Wardlaw, de Zoppo, Yamaguchi, & Berge2003)

Overall, this evidence suggests that thrombolytic therapy may increase independent survival in

many patients despite causing intracranial haemorrhage in others. Whilst it is already clear that

some highly selected patients with stroke will benefit from thrombolytic therapy there is far less

data on thrombolytic therapy for stroke than, for example, for myocardial infarction (MI).

(Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative Group 1994) By the time thrombolysis for MI

was routine, some 60,000 patients had been included in the major trials. (Fibrinolytic Therapy

Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative Group 1994) The relative lack of stroke data has resulted in very

little use of thrombolytic therapy in the UK. Treatment remains controversial and doctors are

uncertain of the benefits of treatment. It is with this background that a further trial evaluating

thrombolysis has been developed and this trial, the Third International Stroke Trial (IST-3),

started recruitment in May 2000 in the UK.

The Third International Stroke Trial (IST-3)

The third International Stroke Trial is an international collaborative trial funded independently

from the pharmaceutical industry with a trial co-ordinating office based at the University of

Edinburgh. A detailed protocol for the IST-3 is available on the Internet

(http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/ist3), but in brief, this trial is a randomised controlled trial evaluating

alteplase (rt-PA) for patients with acute ischaemic stroke.

The main eligibility criteria for the IST-3 are shown in Table 2

Table 2. Main eligibility criteria for the Third International Stroke Trial (IST-3)

Clinically definite stroke with a known time of onset

Computerised tomography (CT) brain scanning has excluded intracranial haemorrhage and

mimics of acute stroke (e.g. brain tumour)

Appropriate consent has been obtained

Treatment started as early as possible, and no later than 6 hours after stroke onset

Trial treatment consists of alteplase in a dose of 0.9mg/kg up to a maximum of 90mg

given as a 10% intravenous bolus and the rest of the dose as a 1-hour intravenous

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (3 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

infusion. Control patients were given matching placebo in the early phase of the trial

described in this paper (2000 – 2002).

Non-trial thrombolytic treatment

In the absence of a license for alteplase for acute stroke in the United Kingdom, few

patients receive routine thrombolysis treatment. However, there is a licence for stroke,

for patients who can treated within 3 hours of stroke onset, in the United States of

America, Germany and Canada. Treatment has to be administered within 3 hours of

stroke onset and published guidelines from North America are available.(Special Writing

Group of the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association 1996) These guidelines

provide some useful information but are difficult to implement in the United Kingdom

(UK), as the health services, and stroke services differ so much between North America

and the UK. This prompted research to develop core nursing standards appropriate to

the NHS, based on the North American guidelines and the experience of implementing

thrombolysis (mainly in the context of the IST-3) in UK centres.

Nursing requirements are exactly the same whether patients receive trial (e.g. IST-3

treatment), with a 50% chance of receiving alteplase, or routine treatment, with 100%

receiving alteplase.

METHODS

The Stroke Association funded pilot and service development phase of the IST-3 covers

the period from February 2000 to January 2003. Multicentre Research Ethics Approval

was obtained in 1999. During this period centres in the United Kingdom (and abroad)

with local ethics committee approval developed fast-track thrombolysis protocols and

sought appropriate patients for the trial. Centres in the UK were asked to nominate a

member of nursing staff with an interest in stroke. There was some financial aid (from

the Stroke Association grant) to assist NHS staff support this research, which was about

0.1 whole time equivalent funding per centre.

The IST-3 Nurse Collaborative Group consisted of the Principal Investigator, Trial

Manager and Medical Research Fellow for the trial and one or more nurses from each UK

centre. The collaborative group met three times. The meetings were structured with

presentations by each participant, and there was ample time for discussion. The

prespecified aims of the meetings were to share knowledge, disseminate good practice

and to learn from the experiences of others. Core nursing standards, appropriate for

thrombolysis in the UK, were discussed, agreed and redrafted by the collaborative

group.

RESULTS

The Stroke Association start-up phase of the IST-3 commenced in Edinburgh in May

2000 and 11 UK centres obtained full ethics approval. The first two meetings of the

collaborative groups discussed the local barriers to recruiting patients in the IST-3.

Barriers to the introduction of thrombolysis for ischaemic stroke in the NHS

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (4 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

The practical barriers to the introduction of thrombolysis for ischaemic stroke in the UK

included:

● Lack of nursing knowledge about thrombolysis for stroke

● Lack of necessary skill mix in stroke centre

● Lack of fast-track organisation

● Nursing fears of the intracranial haemorrhagic side effects

● Lack of appropriate stroke unit beds

● Consent issues

Lack of knowledge about thrombolysis for stroke:

A lack of knowledge about thrombolysis was a considerable barrier to the introduction

of a thrombolysis service in most UK hospitals. Indeed, many of the group admitted

uncertainties themselves. Stroke unit staff needed to keep up to date with the current

information about thrombolysis. Nursing staff were often unaware of the promising data

to support the use of thrombolysis for some highly selected patients (Wardlaw et al

2003) e.g. younger (< 80 years) patients who can be treated within 3 hours of stroke

onset), and that thrombolysis may be beneficial for many more patients (such as those

suitable for the IST-3 trial). (Wardlaw at al, 2003). The group rapidly realised that stroke

thrombolysis teams had an ongoing responsibility to educate all staff including nursing

staff.

Necessary skill mix on stroke unit:

Thrombolysis for stroke can have serious complications and at present it can only be

recommended for organised stroke services, e.g. hospitals with a stroke unit. The

introduction of thrombolysis is an important service development for acute stroke

services. Thrombolysis services will need to be funded (i.e. with health improvement

plans or research and development funding). Local co-ordinators, in discussion with

nurse managers need to ensure that a suitable skill mix is available to safely deliver a

thrombolysis service. In some centres, this may mean limiting thrombolysis to "office

hours" when more support is immediately available. Acute stroke unit areas will need to

be developed. Each shift should include at least one staff nurse who has been trained in

stroke thrombolysis.

In addition many centres have only one stroke consultant prepared to supervise a

thrombolysis service. This is a major barrier. The National Service Framework for Older

People emphasised the importance of a stroke consultant in every hospital but there are

a lack of suitably trained physicians in the UK (DoH, 2001) .This situation should

improve; in the meantime, stroke physicians should consider involving other physicians

or neurologists to share the caseload. This is especially important for out-of-hours

consultant support for nursing and medical staff.

Lack of fast-track organisation:

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (5 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

The three centres with the best recruitment (Western General Hospital, Edinburgh,

Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge and Arrowe Park Hospital, The Wirral) had

organised fast-track stroke systems. The Western General Hospital had an integrated

care pathway that was developed by a multidisciplinary task force and was very effective

in identifying suitable patients for the acute stroke team. Arrowe Park hospital had an

acute stroke pathway, and its stroke service was awarded an NHS Beacon.

Addenbrookes hospital had an acute stroke pathway. Organisation of stroke admissions

by pathways of care, agreed by multi-disciplinary members is key to successful acute

stroke assessment.

Fear of side effects and medico-legal protection for nursing staff:

Both doctors and nurses fear the haemorrhagic complications of thrombolytic treatment,

especially major extra cranial bleeding (e.g. massive gastrointestinal bleeding) or

intracranial bleeding (e.g. severe or fatal recurrent stroke or deterioration). However, the

frequency of these risks is similar to the frequency of complications in the natural

history of a major ischaemic stroke. (Bamford et al, 1990) In legal terms this is called

"minimal risk". Although the risks of thrombolysis are greater than many typical medical

treatments, the risks of the natural history of stroke are greater than many typical

medical conditions. (Bamford, et al,1990) The risks of thrombolysis can, therefore, be

compared to the risks of cerebral oedema in some patients with untreated ischaemic

stroke. Consumer work has emphasised that older people are comfortable with a risk of

death IF there is a chance of future independence.(Koops & Lindley 2002). A simple

analogy is to compare thrombolysis for stroke to major surgery. There are definite risks,

but potential major advantages. In Koops’s study, older people supported research for

thrombolysis despite these increased risks. If patients are given alteplase treatment, it is

very important that informed consent is obtained from the patient (and relatives if

medically appropriate). The IST-3 has strictly controlled consent procedures with full UK

Multi-Centre Research Ethics approval. NHS Trusts should provide management

approval for non-licensed use of alteplase and management approval is mandatory for

clinical trials such as IST-3. These formal approval mechanisms help provide

medico-legal protection for nursing staff.

Lack of appropriate beds:

Many acute NHS hospitals (and stroke units) have average bed occupancy of greater

than 95%, which predicts regular bed crises. (Bagust, et al, 1999) Stroke thrombolysis

needs to be given the priority afforded to thrombolysis for acute MI. Ideally, acute stroke

units need to keep a bed for the next potential thrombolysis patient, or have a strategy

for clearing a bed within an hour. This has been a recurring problem in the IST-3 hospital

centres. However, liaison with bed management, a written protocol and a dedicated

stroke unit bed are some solutions to this problem. It is vital that a bed is protected for

stroke thrombolysis to ensure that treatment is always given in a safe environment with

trained and experienced staff.

Consent issues:

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (6 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

Consent for thrombolysis creates unique ethical dilemmas and there are considerable

problems to overcome.(Lindley 1998) However, the unique consumer involvement in the

design of the IST-3 has created a streamlined and ethical consent process that has

worked well so far. (Koops & Lindley, 2002)

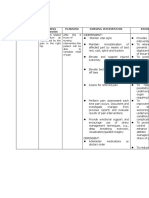

Core Nursing Requirements

There are 10 requirements for the safe delivery of thrombolysis for patients with acute

stroke. These are shown in Table 3 and are discussed below:

Table 3. Core nursing requirements for safe thrombolysis

Triage nursing in the emergency room

Urgent skilled medical assessment in a safe environment

Communication and support

Quick and safe transfer to Computerised tomographic (CT) brain scanning

Monitoring and nursing prior to treatment

Treatment

Monitoring and nursing during and after treatment

Comprehensive assessment in a stroke unit

Preventing and treating complications

Hospital Discharge or transfer to rehabilitation

Triage nursing in the emergency room:

"Time is brain" is a useful phrase to help persuade health professionals identify suitable

patients quickly. Emergency room triage nurses need to follow an appropriate

"fast-track" protocol to activate the acute stroke team. The triage guideline for the

Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. An example of an emergency room triage nurse protocol for thrombolysis

Clinical signs of definite acute stroke Yes/No

Time of onset known Yes/No, if yes state time __: __ (24 hour clock)

Time from stroke onset < 5 hours Yes/No

If Yes to all three questions contact acute stroke team

Initial triage nursing includes functional documentation of airway, breathing and

circulation. Blood pressure, pulse, oxygen saturation and blood glucose estimation

should be performed, and abnormalities treated according to local protocol and medical

advice. An important stroke mimic is hypoglycaemia (Libman et al 1995). The Glasgow

Coma Scale (GCS) should be recorded and vital signs monitored regularly. A peripheral

Intravenous catheter should be inserted. Patients who are in acute urinary retention

should be catheterised. Aspirin and heparin treatment should be avoided during the first

24 hours after treatment with thrombolysis. (The National Institute of Neurological

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (7 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group 1995)

Urgent skilled medical assessment in a safe environment:

Patients who are being considered for thrombolytic treatment need an expert medical

assessment to document the time of stroke onset and to determine the severity of the

stroke. Other mimics of acute stroke include migraine, seizures, metabolic disturbances

and brain tumours. (Libman et al. 1995) An important part of the clinical assessment is

getting a confirmatory history from relatives (or ambulance staff). Relatives should be

advised to remain with the patient until the medical staff have spoken with them and

obtained consent for treatment if appropriate. During this time the nursing priorities

should include monitoring oxygen saturation, documenting blood pressure, pulse and

temperature.

Communication and support:

During this early period it is essential to prepare the patient and relatives for the next

stage of assessment with clear and simple advice. Written information is helpful, for

example, the IST-3 trial information leaflet (available on the British Medical Journal

website at: http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/325/7361/415/DC1). Relatives should be

encouraged to accompany the patient until eventual arrival on the stroke unit, as they

are often required to help with consent issues for those who are drowsy, aphasic or

confused. Nurses have an important role in relieving anxiety in the patients and relatives

by the provision of information (both verbal and written), reassurance and explanation.

Transfer to CT brain scanning:

If the medical staff assess that the patient is potentially eligible for thrombolytic therapy

an urgent computerised tomogram (CT) brain scan must be obtained. Patients should be

transferred on a trolley (not a chair, even if only a mild stroke deficit) to facilitate transfer

onto the CT scanning table. Valuable time is saved if patients can be transferred easily

from trolley to CT scanning table and back onto the trolley at the end of the procedure. A

nurse must accompany the patient to monitor his/her neurological status, vital signs and

to assist in the transfers.

Monitoring and nursing care prior to treatment :

Vital signs need to be rechecked before treatment with thrombolytic therapy. American

guidelines suggest that thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated if blood pressure is

greater than 185/110 mmHg. (Adams Jr. et al, 1996) Some clinicians will initiate

emergency blood pressure lowering in this situation, but this policy is controversial, as

there is some data to suggest that lowering blood pressure in the acute phase of stroke

is harmful. (Brott et al, 1998) Nursing staff have an important role in facilitating

communication at all stages of the fast-tracking process.

Treatment with thrombolysis:

When patients are eligible and have consented to thrombolytic therapy, treatment must

be given without delay. Consideration should be given to where therapy is started. If the

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (8 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

acute stroke unit is a short distance away, patients should be urgently transferred to the

unit. If the acute stroke unit is some distance from the CT scanner, a convenient

treatment room should be identified. The treatment room should provide 24-hour access

to alteplase (or trial treatment packs), giving set equipment and an intravenous infusion

pump. Alteplase is given by an intravenous bolus injection followed by a 1-hour

infusion. The dose is calculated at 0.9mg/kg body weight up to a maximum of 90mg, 10%

is given over 1-2 minutes and the remaining 90% is infused intravenously over 1 hour.

The patients’ weight should be estimated to calculate the correct dose. While the bolus

dose is being administered over 1 - 2 minutes, the 1-hour infusion should be prepared.

The infusion is best given by a syringe driver.

Monitoring and nursing care during and after treatment:

Blood pressure and pulse should be monitored at the start of treatment, at 30 minutes

and at the end of treatment at 1 hour. Our experience has shown blood pressure cuffs

can sometimes cause petechial subcutaneous bleeding; therefore automated blood

pressure machines, that use high-inflation pressures, should be avoided. We, therefore,

recommend that a handheld manual sphygmomanometer be used during thrombolytic

treatment and in the 24 hours following treatment. The patient’s neurological status

should be directly observed during the first 24-48 hours. The GCS should be part of a

minimum nursing assessment and recorded on a bedside chart. The medical staff

should be called if the GCS falls during this period. In our experience patients rarely

deteriorate during the actual alteplase infusion but if the neurological deficit worsens, or

if the patient becomes haemodynamically unstable, the infusion should be halted and

the doctor called. The main risk of thrombolytic treatment is intracranial haemorrhage

and if the patient deteriorates neurologically (Adams et al 1996) (e.g. the GCS falls)

during or after treatment, an urgent CT brain scan should be performed to exclude

haemorrhagic transformation of the cerebral infarct, or other intracranial bleeds.

Thrombolysis with rt-PA is clot specific, i.e. it mainly exerts its effect within the

thrombus (The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke

Study Group (1995) so although the rt-PA has a very short half-life in the circulation

(minutes), the drug will continue to act in a thrombosis for many hours. Therefore the

potential haemorrhagic complications may be delayed for 24-48 hours.

At about 24-48 hours following thrombolysis treatment the excess risks of bleeding start

to diminish and it is common practice to obtain a second CT brain scan to help exclude

any intracranial bleeding complications. If there have been no bleeding complications,

aspirin is usually started (or recommenced) (Chen et al 2000). Heparin is not used

routinely as there is no evidence that early anticoagulation is required after

thrombolysis for stroke, and early anticoagulation is not effective for ischaemic stroke.

(Gubitz et al 2003)

Comprehensive assessment in a stroke unit:

The benefits of stroke unit care are applicable to patients with all types of stroke and it is

important that all patients who are considered for thrombolysis have access to stroke

unit care (or stroke team care). The treatment benefits of being in a stroke unit are

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (9 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

considerable (equivalent to about 60 per 1,000 extra independent survivors compared to

about 20-30 per thousand survivors for early thrombolysis of acute myocardial

infarction). (Stroke Unit Trialists'2001) (Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative

Group 1994) Hospitals without a stroke unit should invest in stroke services prior to

setting up a stroke thrombolysis service. A major feature of the stroke units in the

randomised controlled trials was comprehensive assessment by trained

multi-disciplinary staff.(Stroke Unit Trialists'2001)

Preventing and treating complications:

Nurses have a major role to play in the prevention of complications following

thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Patients need to be carefully observed to

identify any signs of bleeding or bruising. Invasive procedures such as urinary

catheterisation should be avoided if possible, to avoid causing any trauma which might

result in bleeding. Care must be taken when removing indwelling intravenous catheters,

as there may be excessive bleeding. During this risky period nursing care plans or

nursing pathways need to pay particular attention to patient safety. This is especially

important if the patient has sensory inattention or neglect. Consideration should be

given to providing one-to-one nursing for the initial 24 hours of treatment. In general,

there should be no restrictions on usual early rehabilitation strategies for patients.

Hospital Discharge or transfer to rehabilitation:

Patients who continue to need nursing support and rehabilitation should be nursed in a

stroke rehabilitation unit. Hospitals without well-organised stroke services need to

invest in these before even considering introducing thrombolytic therapy. If this unit is

off the main acute hospital site it is very important to ensure a good handover of care.

Patients who regain full independence on the acute stroke unit will need information

about their stroke, counselling regarding modifiable risk factors e.g. smoking and this

can be reinforced using written material and videos from the Stroke Association and

Chest, Heart and Stroke, Scotland.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has outlined the rationale for introducing thrombolysis for acute ischaemic

stroke in the UK and has discussed the nursing issues that need to be considered when

writing a local protocol and developing a thrombolysis service. Education was an

important theme to emerge from our research, and new stroke services should ensure

that resources are allocated for continued professional development for stroke nurses.

The introduction of a thrombolysis service will also need investment in nursing time and

expertise, with appropriate staffing levels to manage the detailed nursing described in

this paper. The continued development of stroke units within the United Kingdom should

facilitate the introduction of a thrombolysis service.

We would welcome comments and contributions from other with similar experience in

the UK.

Acknowledgements

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (10 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

This work was supported by the Stroke Association grant TSA04/99 "Thrombolysis for

acute ischaemic stroke: pilot and service development phase of the Third International

Stroke Trial (IST-3)", University of Edinburgh and the Scottish National Health Service

(Dr Lindley).

We thank the patients and their relatives who agreed to participate in IST-3 and to the

many hundreds of NHS and University staff who have contributed their time and effort to

this project.

Key Points

● Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke is a promising treatment requiring

further development before becoming a routine treatment in UK hospitals.

● In the UK, the Third International Stroke Trial (IST-3) is the major ongoing trial

of alteplase, the most promising thrombolytic agent.

● This study identified many barriers to a routine stroke thrombolysis service in the

UK NHS, including lack of available beds, knowledge and perceived fears of

treatment.

● Solutions to many of the identified barriers were identified and implemented, such

as regular education updates for stroke service staff and the routine use of stroke

pathways or protocols.

● This research has led to the development of core nursing requirements that are

practicable for the UK NHS.

Appendix: IST-3 Stroke Nurse Collaborative Group

Julie Rycarte, Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge

Pamela Beattie, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast

Diane Day, Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge

Sandra Aitcheson, Ulster Hospital, Belfast

Annemarie Hunter, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast

Ruth Plant, Arrowe Park Hospital, Wirral

Diane Rennie, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh

Pat Taylor, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (11 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

Doreen Shaw, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh

Denise Shave, Royal Bournemouth Hospital

Ally Graham, Royal Bournemouth Hospital

Karen Innes, Trial Manager, Edinburgh

Peter Hand, Research Fellow, Edinburgh

Richard Lindley, Principal Investigator, Edinburgh

Steve Duckworth, King’s College Hospital, London

Diane Thompson, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield

Emma Jackson, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds

Karen Coyle, University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool

Tracy McCormick, University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool

Cheryl Utecht, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester

References

Adams HPJr, Brott TG, Furlan A J et al (1996) Guidelines for thrombolytic therapy for

acute stroke: a supplement to the guidelines for the management of patients with acute

ischemic stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a Special Writing Group

of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association Circulation 94:1167-74.

Bagust A, Place M, Posnett J (1999) Dynamics of bed use in accommodating emergency

admissions: stochastic simulation model. Br Med J 319:155-8

Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M et al (1998) A prospective study of acute

cerebrovascular disease in the community: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke

Project1981-6. 1, Methodology, demography and incident cases of first-ever stroke.J

Neurol, Neurosurgery Psychiatry 51: 1373-80.

Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M, Burn J, Warlow C (1990) A prospective study of

acute cerebrovascular disease in the community: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke

Project 1981-1986. 2; Incidence, case fatality and overall outcome at one year of cerebral

infarction, primary intracerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage", Journal

of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, vol. 53, pp. 16-22.

Brott, T. Lu M, Kothari R et al (1998) Hypertension and its treatment in the NINDS rt-PA

Stroke Trial. Stroke 29:1504-9.

Councell, C, Collins, NINDS rt_PA Stroke Study Group (1998) Stroke 29: 1504-9.

Chen ZM, Sandercock P, Pan et al (2000) Indications for early aspirin use in acute

ischemic stroke: a combined analysis of 40 000 randomised patients from the Chinese

acute stroke trial and the international stroke trial. On behalf of the CAST and IST

collaborative groups. Stroke 31:1240-9.

DoH (2001) Standard five: stroke. In: National Service Framework for Older People. DoH,

London.

Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative Group (1994) Indications for

fibrinolytic therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction: collaborative overview of

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (12 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

early mortality of early mortality and major morbidity results from all randomised trials

of more than 1000 patients. Lancet 343: 311-22.

Gubitz G, Counsell C, Sandercock P, Signorini D. (2003) Anticoagulants for acute

ischaemic stroke (Cochrane Review). 1 edn, Update Software, Oxford.

Isard PA, Forbes JF (1992) The Cost of Stroke to the NHS in Scotland. Cerebrovascular

Dis 2: 47-50.

Koops L, Lindley RI (2002) Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke: consumer

involvement in design of new randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 325: 415-17.

Libman RB, Wirkowski E, Alvir J, Rao H (1995) Conditions that mimic stroke in the

emergency department: implications for acute stroke trials Arch Neurol 52: 1119-22.

Lindley RI 1998,Thrombolytic treatment for acute ischaemic stroke: consent can be

ethical. Br Med J 316:1005-7.

Rothwell PM (2001) The high cost of not funding stroke research: a comparison with

heart disease and cancer. Lancet 357:1612-16.

Sandercock PAG, Celani MG, Ricci S (1992) The likely public health impact in Europe of

simple treatments for acute ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovascular Dis 2: 236.

Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association (1996)

Guidelines for thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke: a supplement to the guidelines for

the management of patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Stroke, 27: 711-18.

Stroke Unit Trialists C (2001) Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke, Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews 1: 2001.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group

(1995) Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. New Engl J Med 333:

1581-7.

Wardlaw JM, de Zoppo G, Yamaguchi T, Berge, E (2003) Thrombolysis for Ischaemic

Stroke (Cochrane Review). 1 edn, Update Software, Oxford.

Table 5 Trials of thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke.

Abe 1981 (Abe 1981)

Atarashi 1985 (Atarashi et al. 1985)

Ohtomo (Atarashi, Otomo, Araki, Itoh, Togi, & Matsuda1985)

Mori (Mori et al. 1992)

Haley (Haley et al. 1993)

JTSG (Yamaguchi et al. 1993)

ECASS 1 (European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study Group 1995)

Morris (Morris et al. 1995)

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (13 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

MAST Italy (Multicentre Acute Stroke Trial - Italy (MAST-I) Group 1995)

NINDS (The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group 1995)

ASK 1996 (Donnan et al. 1996)

MAST Europe (The Multicenter Acute Stroke Trial - Europe Study Group 1996)

PROACT (del Zoppo et al. 1998)

ECASS 2 (Hacke et al. 1998)

ATLANTIS B (Clark et al. 1999)

PROACT II (Furlan et al. 1999)

ATLANTIS A (Clark et al. 2000)

Chinese UK Trial (full publication awaited) (Wardlaw et al. 2003)

Detailed summaries of the trials are available in the Cochrane Library review (Wardlaw, de Zoppo,

Yamaguchi, & Berge2003)

References

Abe, T. 1981, "Clinical evaluation for efficacy of tissue cultured urokinase on cerebral

thrombosis by means of multi-centre double blind study", Blood and Vessel, vol. 12, pp.

321-341.

Atarashi, J., Otomo, E., Araki, G., Itoh, E., Togi, H., & Matsuda, T. 1985, "Clinical utility of

urokinase in the treatment of acute stage of cerebral thrombosis (Multicentre

double-blind study in comparison with placebo)", Clinical Evaluation, vol. 13, pp.

659-709.

Clark, W. M., Albers, G. W., Madden, K. P., Hamilton, S., & for the Thrombolytic Therapy

in Acute Ischaemic Stroke Study Investigators 2000, "The rt-PA (Alteplase) 0- to 6- hour

Acute Stroke Trial, Part A (A027g). Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled,

multicentre study.", Stroke, vol. 31, pp. 811-816.

Clark, W. M., Wissman, S., Albers, G. W., Jhamandas, J., Madden, K., & Hamilton, S.

1999, "Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (Alteplase) form ischaemic

stroke 3 to 5 hours after symptom onset. The Atlantis Study: a randomised controlled

trial", JAMA, vol. 282, pp. 2019-2026.

del Zoppo, G., Higashida, R. T., Furlan, A. J., Pessin, M. S., Rowley, H. A., Gent, M., & and

the PROACT Investigators 1998, "A phase II randomised trial of recombinant

pro-urokinase by direct arterial delivery in acute middle cerebral artery stroke", Stroke,

vol. 29, pp. 4-11.

Donnan, G. A., Davis, S. M., Chambers, B. R., Gates, P. C., Hankey, G. J., McNeil, J. J.,

Rosen, D., Stewart-Wynne, E. G., Tuck, R. R., & for the Australian Streptokinase (ASK)

Trial Study Group 1996, "Streptokinase for acute ischemic stroke with relationship to

time of administration", JAMA, vol. 276, pp. 961-966.

European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study Group 1995, "European Cooperative Acute

Stroke Study (ECASS). Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen

activator for acute hemispheric stroke", JAMA, vol. 274, pp. 1017-1025.

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (14 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

Furlan, A. J., Higashida, R. T., Wechsler, L., Gent, M., Rowley, H. A., Kase, C., Pessin, M.,

Ahuja, A., Callahan, F., Clark, W. M., Silver, F., Rivera, F., & for the PROACT Investigators

1999, "Intraarterial Pro-Urokinase for acute ischaemic stroke. The PROACT II Study: A

randomised controlled trial", JAMA, vol. 282, pp. 2003-2011.

Hacke, W., Kaste, M., Fieschi, C., von Kummer, R., Davalos, A., Meier, D., Larrue, V.,

Bluhmki, E., Davis, S., Donnan, G., Schneider, D., Diez-Tejedor, E., Trouillas, P., & for

second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators 1998, "Randomised

double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase

in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II)", The Lancet, vol. 352, pp. 1245-1251.

Haley, E. C., Brott, T. G., Sheppard, G. L., Barsan, W., Broderick, J., Marler, J. R.,

Kongable, G. L., Spilker, J., Massey, S., Hansen, C. A., Torner, J. C., & for the TPA

Bridging Study Group 1993, "Pilot randomised trial of tissue plasminogen activator in

acute ischaemic stroke", Stroke, vol. 24, pp. 1000-1004.

Mori, E., Yoneda, Y., Tabuchi, M., Yoshida, T., Ohkawa, S., Ohsumi, Y., Kitano, K.,

Tsutsumi, A., & Yamadori, A. 1992, "Intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen

activator in acute carotid artery territory stroke", Neurology, vol. 42, pp. 976-982.

Morris, A. D., Ritchie, C., Grosset, D. G., Adams, F. G., & Lees, K. R. 1995, "A pilot study

of streptokinase for acute cerebral infarction", Quarterly Journal of Medicine, vol. 88, pp.

727-731.

Multicentre Acute Stroke Trial - Italy (MAST-I) Group 1995, "Randomised controlled trial

of streptokinase, aspirin, and combination of both in treatment of acute ischaemic

stroke", The Lancet, vol. 346, pp. 1509-1514.

The Multicenter Acute Stroke Trial - Europe Study Group 1996, "Thrombolytic therapy

with streptokinase in acute ischemic stroke", The New England Journal of Medicine, vol.

335, pp. 145-150.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group

1995, "Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke", The New England

Journal of Medicine, vol. 333, pp. 1581-1587.

Wardlaw, J. M., de Zoppo, G., Yamaguchi, T., & Berge, E. 2003, Thrombolysis for

ischaemic stroke (Cochrane Review), 1 edn, Update Software, Oxford.

Yamaguchi, T., Hayakawa, T., Kiuchi, H., & for the Japanese Thrombolysis Study Group

1993, "Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator ameliorates the outcome of hyperactue

embolic stroke", Cerebrovascular Diseases, vol. 3, pp. 269-272.

Organisations

Chest, Heart & Stroke Scotland

65 North Castle Street, Edinburgh EH2 3LT

Advice Line: 0845 077 6000

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (15 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

The development of a stroke nurse protocol for delivering thrombolyti... for patients with acute ischaemic stroke in United Kingdom hospitals

Tel 0131 225 6963 Fax 0131 220 6313

E-mail: admin@chss.org.uk

Web: www.chss.org.uk

Stroke Association

Stroke House, 240 City Road, London, EC1V 2PR

Tel 020 7566 0300 Fax 020 7490 2686

http://www.stroke.org.uk/

info@stroke.org.uk

Correspondence Mrs Karen Innes, Trial Manager, IST-3

Bramwell Dott Building, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital

Edinburgh, EH4 2XU

Tel 0131 5372793 Fax 0131 332 5150

http://www.dcn.ed.ac.uk/newist3/nurse_protocol_article.htm (16 of 16) [13/05/2003 11:59:06]

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Casper Cheat SheetDocument3 pagesCasper Cheat SheetMichael Moore100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Teamwork Skill Communicating Effectively in GroupDocument21 pagesTeamwork Skill Communicating Effectively in Groupsiyalohia8No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Japanese Foods That Heal - Using Traditional Japanese Ingredients To Promote Health, Longevity, & Well-Being (PDFDrive)Document282 pagesJapanese Foods That Heal - Using Traditional Japanese Ingredients To Promote Health, Longevity, & Well-Being (PDFDrive)Stanislava KirilovaNo ratings yet

- Nursing ManagementDocument10 pagesNursing ManagementMohamed Abd El MonemNo ratings yet

- Adult Basic Life Support (BLS)Document50 pagesAdult Basic Life Support (BLS)Mohamed Abd El MonemNo ratings yet

- Nursing and Interdisciplinary of StrokeDocument36 pagesNursing and Interdisciplinary of StrokeMohamed Abd El MonemNo ratings yet

- NA Curriculum 01-16Document37 pagesNA Curriculum 01-16Mohamed Abd El MonemNo ratings yet

- Obat Program Puskesmas Des 2020Document28 pagesObat Program Puskesmas Des 2020WIWIK FADILAH AMIRNo ratings yet

- EPI 3.6 Qualitative ResearchDocument5 pagesEPI 3.6 Qualitative ResearchJoher MendezNo ratings yet

- Legal ComplianceDocument14 pagesLegal ComplianceArun FikdetcNo ratings yet

- NCP (Acute Pain)Document1 pageNCP (Acute Pain)Joan QuebalayanNo ratings yet

- SNEHADocument2 pagesSNEHAanishNo ratings yet

- MSDS X20 PlasterboardsDocument2 pagesMSDS X20 PlasterboardstantanNo ratings yet

- Sacandalfinal31 PDFDocument69 pagesSacandalfinal31 PDFJoshua KumayogNo ratings yet

- IELTS Essay - Public HealthDocument5 pagesIELTS Essay - Public HealthAnonymous j8Ge4cKINo ratings yet

- Elma-T3: Mammography SystemDocument12 pagesElma-T3: Mammography SystemKateNo ratings yet

- Blue and White Modern Creative Business PresentationDocument14 pagesBlue and White Modern Creative Business PresentationDaine GoNo ratings yet

- Module 1 HOME-ECONOMICS-LITERARCYDocument44 pagesModule 1 HOME-ECONOMICS-LITERARCYAaron Miguel Francisco100% (1)

- Safety Data Sheet: Product Name: MOBIL EAL 224HDocument10 pagesSafety Data Sheet: Product Name: MOBIL EAL 224HAnibal RiosNo ratings yet

- 20-Dialysis 2016Document10 pages20-Dialysis 2016duchess juliane mirambelNo ratings yet

- Technology PresentationDocument16 pagesTechnology Presentationabraralnaamani3No ratings yet

- Dr. Fixit Fastflex: High Performance Polymer Modified Cementitious CoatingDocument3 pagesDr. Fixit Fastflex: High Performance Polymer Modified Cementitious CoatingDeep GandhiNo ratings yet

- 09 7 Strategies For Effective TrainingDocument44 pages09 7 Strategies For Effective TrainingJaiDoms100% (1)

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris Ling Ling WeiDocument2 pagesTugas Bahasa Inggris Ling Ling WeiLing Ling Wei IINo ratings yet

- Colorectal Cancer EngDocument11 pagesColorectal Cancer Engrinadi_aNo ratings yet

- Disaster Management Regulatory FrameworkDocument38 pagesDisaster Management Regulatory FrameworkJames LoganNo ratings yet

- Warning: Company Profile Disclaimer of Warranties and Limitation of LiabilityDocument10 pagesWarning: Company Profile Disclaimer of Warranties and Limitation of Liabilitybman0051401No ratings yet

- HTP Technique Lecture Notes 1Document9 pagesHTP Technique Lecture Notes 1Rameen FatimaNo ratings yet

- Ferrous Sulphate - MSDSDocument6 pagesFerrous Sulphate - MSDSDyeing DyeingNo ratings yet

- The Role of Parents in Sex Education: How Can Parents Be Better Equipped To Provide Accurate and Comprehensive Information To Their Children?Document7 pagesThe Role of Parents in Sex Education: How Can Parents Be Better Equipped To Provide Accurate and Comprehensive Information To Their Children?RaashiNo ratings yet

- Assessing Special PopulationsDocument91 pagesAssessing Special PopulationsJAGATHESANNo ratings yet

- JSS Medical College Mysore: Admissions 2023, Courses Offerd, Fees Structure, Cutoff, CounsellingDocument27 pagesJSS Medical College Mysore: Admissions 2023, Courses Offerd, Fees Structure, Cutoff, CounsellingJustGetAdmissionNo ratings yet

- Reason For The Critical Equipment Maintenance (Tick One)Document1 pageReason For The Critical Equipment Maintenance (Tick One)Anil RainaNo ratings yet

- An Overview Storage of Pharmaceutical Products PDFDocument18 pagesAn Overview Storage of Pharmaceutical Products PDFVer OnischNo ratings yet