Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chambliss 1995

Uploaded by

María José ValenzuelaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chambliss 1995

Uploaded by

María José ValenzuelaCopyright:

Available Formats

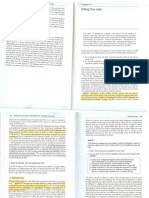

Text Cues and Strategies Successful Readers Use to Construct the Gist of Lengthy

Written Arguments

Author(s): Marilyn J. Chambliss

Source: Reading Research Quarterly , Oct. - Nov. - Dec., 1995, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Oct. - Nov.

- Dec., 1995), pp. 778-807

Published by: International Literacy Association and Wiley

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/748198

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/748198?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wiley and International Literacy Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Reading Research Quarterly

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Reading Research Quarterly

Vol. 30, No. 4

October/November/December 1995

Marilyn J. Chambliss ?1995 International Reading Association

(pp. 778-807)

University of California, Berkeley, California, USA

Text cues and strategies successful

readers use to construct the gist of

lengthy written arguments

Lengthy written argument is an important form of had few encounters with lengthy written argument may

communication. In newspaper editorials, maga- not know how authors cue claims and evidence in

zine articles, and books, authors offer evidence for lengthy text nor have the necessary strategies to make

claims, their arguments spanning several para- use of the cues to reconstruct a mental representation of

graphs, a number of sections, or even many chapters. the argument.

Work by Gilbert (1991) suggests that readers who suc- Although it is risky to infer possible instructional

cessfully comprehend a lengthy argument must mentally approaches based on what successful readers do, identi-

represent the author's claim and evidence as it is re- fying the text cues and strategies they use is a plausible

vealed across at least several paragraphs of text. Only first step. This work relied on Toulmin's three-part mod-

those readers who have successfully comprehended the el of argument (Toulmin, 1958), Meyer's text compre-

argument will be prepared to weigh the evidence and hension model (Meyer, 1985; Meyer, Brandt, & Bluth,

accept or reject the claim (Kuhn, 1992). 1980), and a framework of text structures (Calfee &

Unfortunately, a sizeable proportion of readers Chambliss, 1987; Chambliss, 1994a; Chambliss & Calfee,

may reach adulthood never learning how to represent 1989, in press) to suggest the text cues and strategies

the claim and evidence in a lengthy written argument. used by competent readers to construct the gist of a

Test results from the National Assessment of Educational lengthy argument. Comprehension of written argument

Progress (NAEP) suggest that the majority of adults in has not been as thoroughly examined as comprehension

the U.S. do not competently comprehend written argu- of other text types (e.g., Meyer & Freedle, 1984). Though

ments longer than a few paragraphs (Kirsch, Jungeblut, it is true that researchers have developed models for

Jenkins, & Kolstad, 1993). Part of the problem may be how people of various ages weigh evidence and accept

lack of practice. Textbook writing, the genre with which or reject claims (e.g., Kuhn, Schauble, & Garcia-Mila,

school-aged readers have the most contact, rarely incor- 1992), they have typically not used reading tasks nor fo-

porates well-written argument of any length. In a survey cused on how people comprehend an argument in the

of nine social studies textbooks (Calfee & Chambliss, first place. Furthermore, comprehension work, customar-

1988) and 12 science textbooks (Chambliss, Calfee, & ily employing texts of one or two short paragraphs (e.g.,

Wong, 1990) for Grades 4-12, Calfee and his colleagues Hare, Rabinowitz, & Schieble, 1989), has neglected to fo-

found only a handful of arguments, each of which was cus on how readers comprehend lengthy text. Neither

no more than a few paragraphs long. Readers who have comprehension research nor work on argument reason-

778

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I ABTRATS

Text cues and strategies successful readers use to construct the gist of lengthy written arguments

COMPREHENSION OF written argument has been less thoroughly grade advanced placement English students read arguments varying

examined than comprehension of other text types, even though, ac- in argument structure, content familiarity, and argument signaling

cording to National Assessment of Educational Progress results, and completed either written survey or think-aloud protocol com-

many adults cannot competently comprehend lengthy written argu- prehension tasks. Both text structure and signaling in introductions

ments (Kirsch, Jungeblut, Jenkins, & Kolstad, 1993). Three experi- and conclusions consistently influenced their responses. They used

ments based on Toulmin's (1958) argument model, Meyer's (1985) these cues to (a) recognize the argument structure in a lengthy text,

comprehension model, and Calfee and Chambliss' (1987) text design (b) identify the claim and evidence, and (c) construct a gist repre-

model identified text cues and comprehension strategies used by sentation. Outcomes have both general theoretical value and practi-

competent readers comprehending lengthy arguments. Eighty 12th cal implications for designing instructional materials.

Pistas textuales y estrategias usadas por los buenos lectores para construir el tema de argumenta-

ciones escritas extensas

LA COMPRENSION de la argumentaci6n escrita no ha sido exami-

zados de ingles de 12Q grado leyeron argumentaciones que varia-

ban en estructura argumentativa, familiaridad de los contenidos y

nada tan profundamente como la comprensi6n de otros tipos de tex-

to, si bien seguin los resultados de NAEP (Evaluaci6n Nacionalsefialamiento

de de argumentaci6n y completaron tareas de compren-

Programas Educativos), muchos adultos no pueden comprender si6n por medio de informes escritos o protocolos de 'pensar en voz

competentemente argumentaciones escritas extensas (Kirsch,

alta'. Tanto la estructura del texto como los sefialamientos en las in-

Jungeblut, Jenkins & Kolstad, 1993). En tres experimentos basados

troducciones y conclusiones influenciaron consistentemente sus res-

en el modelo de argumentaci6n de Toulmin (1958), el modelo puestas.

de Usaron estas pistas para a) reconocer la estructura argu-

comprensi6n de Meyer (1985) y el modelo de disefio textualmentativa

de en un texto extenso, b) identificar la afirmaci6n y la

Chambliss y Calfee (Chambliss, 1987), se identificaron pistas tex-

evidencia y c) construir la representaci6n del tema. Los resultados

tuales y estrategias de comprensi6n usadas por lectores competentes

tienen valor te6rico general e implicancias pricticas para el diseio

de materiales didacticos.

al comprender argumentaciones extensas. Ochenta estudiantes avan-

Texthinweise und Strategien von Lesern, die erfolgreich den Kernpunkt langatmiger Argumentationen

erfassen wollen

DAS TEXTVERSTEHEN geschriebener Erirterungen ist vergleichs-

die sich hinsichtlich ihrer Argumentationsstruktur, inhaltlicher

weise weniger untersucht als das Verstehen anderer Textsorten, Verwandtheit

ob- und Argumentmarkierung unterschieden und legten

wohl laut NAEP-Ergebnissen viele Erwachsene das kompetente entweder einen schriftlichen Bericht vor oder bekamen mondliche

Aufgaben zum Textverstehen. Sowohl die Textstruktur und Hinweise

Lesen lingerer Er6rterungen nicht beherrschen (Kirsch, Jungblut,

Jenkins, Kolstad 1993). Drei Untersuchungen, die auf Toulmins

in den Einleitungen als auch Schlugfolgerungen beeinfluSten ihre

Argumentenmodell (1958) und auf dem Textmodell von Caffee und

Antworten. Sie benutzten die Schlisselstellen, um a) die

Chambliss (1987) beruhen, sollten nun Textschlissel und

Argumentationsstruktur im Langtext zu erkennen, b) Absicht und

Selbstverstdndnis des Textes zu erfassen, und c) das Wesentliche

Verstehensstrategien aufkldren, die von kompetenten Lesem zum

wiederzugeben. Die Ergebnisse haben generellen theoretischen Wert

Verstehen lingerer Abhandlungen eingesetzt werden. 80 fort-

und praktische Implikationen, um Lehrmaterial zu konzipieren.

geschrittene Englischschiiler der 12. Klasse lasen die Er6rterungen,

779

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ABSTRAC,

_tS- 5-Ef AL~~t\d c~E a~~~~~;~`:Qae-5 ; ~ \a

NAEP(National Assessment

?( ?/ of

7"-? Edu-

s T-A ? N 4.%?1f -W -Dk r

cational Progress) Oa*S2 If48 0 AfiAMOA AViON )

t LG4:4

StvC 74!- t7 (Kirsch, rt 0)A W kT 60

Jungeblut,

Jenkins, & Kolstad, 1993). Toulmin

7) A3 M)L jmo)) ? T i , -j U -Ct

(1958) a6Di ( -F- a --E ?f:)L,

Meyer(1985) 0a Y)?f:

"Jz) a>-,

tz &) / 0)c~

I~ tJ~tf~5 ~5f

70) 'U *fA t-a-:

AM I

"=E )t5 , LZUT Chambliss YN tr) 01 L m *a

Calfee

(1987)6D "' x K f+ EMC.

0) -C & 7cD 0

t tz 5_- o YI,,, OD U L OD -A, !,

Indices textuels et stratggies des bons lecteurs pour saisir l'essentiel d'arguments dcrits d'un texte long

ON S'EST moins interesse ' la comprehension de l'argumentation structure argumentative, la familiarite du contenu, le signalement

&crite qu'a celle d'autres types de textes, meme si, suivant la argumentatif,

NAEP et ont effectue des tiches de comprehension utilisant

(Programme National d'Evaluation de l'Education), de nombreux

un questionnaire &crit ou un protocole de verbalisation de la pensee.

adultes ne comprennent pas bien les arguments ecrits d'un texte

Leurs reponses ont et? fortement influences par la structure du texte

long (Kirsch, Jungblut, Jenkins, & Kolstad, 1993). Trois experiences

et par les signalements de l'introduction ou de la conclusion. Ils ont

basees sur le modele argumentatif de Toulin (1958), le modele de

utiliseces indices pour a) reconnaitre la structure argumentative dans

la comprehension de Meyer (1985), et le module de planification un texte

de &tendu, b) identifier le propos et les preuves, et c) construi-

texte de Calfee & Chambliss (1987), ont identifie les indices textuels

re une representation de ce qui est essentiel. Les retombtes ont une

et les strategies de comprehension qu'utilisent des lecteurs experts

valeur theorique genmrale et des implications pratiques pour la fab-

pour comprendre des arguments 6tendus. Quatre vingts 6tudiants rication du material didactique.

d'anglais de 120 annie ont lu des arguments qui variaient suivant la

780

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 781

Figure 1 An argument text diagra

Evidence Warrant Claimhn

Tiny mouse bites snake)

on back repeatedly

until it drops the mouse

that it is holding in its

mouth.

Animals that attack a

much larger predator

show amazing courage.

Birds that attack a

Two geese fight off a Animals can show

predator show amazing

fox. amazing courage.

courage.

Mother animals that risk

their lives to save their

babies show amazing

courage.

A mother skunk

battles a flooded

river to rescue her

trapped babies.

ing has demonstrated the text cues and strategies that ventional structure in written arguments as specified in

successful readers use to comprehend lengthy argument. the rhetoric and a rhetorical schema used by readers to

comprehend argument text. Indeed, at least some current

The Toulmin argument model textbooks in rhetoric and composition explain argument

The study of argument has a long, prestigious histo-structure according to the Toulmin model (e.g., Hairston,

ry. Beginning in antiquity, rhetoricians have analyzed the1992; Ramage & Bean, 1995).

features of effective spoken and written argument (e.g., Figure 1 depicts the structure in a written argument

Aristotle in Cooper, 1932; Bain, 1867; Brooks & Warren, according to the model. Based on the discipline of ju-

1972; Ramage & Bean, 1995). The rhetoric is typically en- risprudence as more representative of real-world argu-

countered today in composition books (e.g., Barnet & ments than syllogistic structures, Toulmin's model has

Stubbs, 1990; Crews, 1992; Hairston, 1992), which uni- three parts: a claim (an assertion analogous to a plea of

formly include chapters on how to craft an argument ac- guilt or innocence), evidence (facts and examples), and a

cording to these rhetorical features (Calfee & Chambliss, warrant (a law-like generalization that links the two). In

1987). Focusing on reasoning instead of writing, logicianssome respects the warrant is the most innovative feature

have developed the logical calculus to represent formalof the model, but also the most elusive and inexplicit.

relations among argument parts (Alexander, 1969; Mates,Toulmin conceived it as analogous to the major premise

1972). The philosopher, Stephen Toulmin (1958), ex- in a classical syllogism and proposed that the warrant is

plained that as logic has become more mathematical, itthe underlying reason offered for accepting or rejecting

has moved away from real-world arguments. Van Dijk the evidence as support for the claim. As such, it often

and Kintsch (1983) suggested that Toulmin's (1958) argu- makes or breaks the argument. Consider the warrant in

ment model could effectively characterize both the con- Figure 1, "Animals that attack a much larger predator

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

782 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

general

show amazing courage." The reader who is reluctant to background knowledge, text knowledge, a

attribute human traits, such as courage, to animals repertoire

may of comprehension strategies assuming a sta

reject this warrant and the claim that it underlies.toward a text with particular features within a social

Toulmin (1958) proposed that the claim-evidence-

text (Ruddell, 1994). This study highlighted certain fe

tures of these models and downplayed others. I hav

warrant structure characterizes an argument independent

of content. Brooks and Warren (1972), echoed by

already hypothesized that competent readers have

ground

Nickerson (1991), point to an interesting ambiguity in knowledge about argument specified by th

Toulmin

the word "argument" itself. As used by the logician or (1958) model as qualified by Pollard (1982

Becauseofthe purpose of argument is to communicat

rhetorician, argument refers to a reasoned justification

some claim. It can be used for any content, as the exam-

author's thinking, I expected readers to take an effer

stance as proposed by Rosenblatt (1978, 1994), whe

ple in Figure 1 would suggest. In common parlance,

they would search for text cues so that they could ab

however, argument is a verbal fight between disputants

(Brooks & Warren, 1972; Nickerson, 1991) where the structure, and remember the claim and its evi

stract,

dence as a mental representation of the text's gist

content is necessarily contentious. The goal for both

(Meyer,

combatants, whether face to face or linked as author and 1985; Spivey, 1987). How well and in what

the text

reader by a text, is to win the argument rather than to cued the argument would also be important.

Readers can be strongly affected by text characterist

accept or reject a claim through reasoning (Nickerson,

(Dole,on

1991). Nickerson's notions suggest that readers intent Duffy, Roehler, & Pearson, 1991), an effect tha

winning an argument have no need to represent the au-

should be particularly potent for readers who have as

thor's argument accurately-to comprehend it-in order

sumed an efferent stance. In order to highlight reade

to weigh evidence and accept or reject a claim. gument

Their knowledge, comprehension processes, and

influence of text features, the study did not focus on

goal, instead, is to build a case for their own "side,"

picking and choosing from the argument the evidence reader general knowledge or the social context f

ther

and claims that match whatever they hold to be true reading.

and

ignoring the rest. According to this second conceptual- Although it does not address written argument per

ization of argument, the text depicted in Figure 1 se,would

a comprehension model proposed and tested by

Meyer and her colleagues (Meyer et al., 1980; Meyer &

not be considered contentious enough to be character-

ized as an argument. Freedle, 1984; Meyer & Rice, 1982) suggests specific

Even reasoned arguments may have important con-

strategies that successful readers may apply when they

tent characteristics, although not of a contentiousassume an efferent stance. According to the model, com-

nature.

In a review of research on reasoning, Pollard (1982) con- know a set of rhetorical structures, or

petent readers

cluded that people typically recognize as claimsschemata

asser-(van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983; Meyer, 1985), that

tions for which they cannot readily remember eitherauthors use to organize text (Meyer & Freedle, 1984). If a

confirming or disconfirming examples or scenarios reader can identify one of these structures in a text, he or

(Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). They can comprehend an for its parts and link them together into a

she can search

text representation. Readers who have used this structure

argument when the warrants and evidence are familiar.

strategy recall the text as a gist, a summary of the impor-

Pollard explained that if the claim is familiar, people

may fail to recognize the presence of an argument. tantIf

content organized comparably to the organization in

warrants and evidence are unfamiliar, they may relythe texton (Kintsch & van Dijk, 1978; Meyer et al., 1980).

what they already know rather than construct a Teaching

repre- less competent readers to find the author's

sentation of the argument presented to them. structure improves their comprehension (Armbruster,

According to Toulmin's model and Pollard'sAnderson,

qualifi- & Meyer, 1991), lending support to the model.

cation, I hypothesized that an unfamiliar claim-familiar Figure 2 displays a three-stage model based on a

synthesis

evidence-familiar warrant pattern appears in written text of Toulmin's (1958) and Meyer's (1985) no-

as a set of argument cues. I also proposed that thetions. pat-

The model portrays the strategies used by compe-

tern characterizes an argument schema known bytent readers to construct the gist of a lengthy written

suc-

cessful readers. I avoided contentious content thatargument.

mightIn this study I hypothesized that competent

cue readers to case build rather than comprehend the

readers use strategies specified by the model.

author's claim and support. In the first stage, as soon as the reader notices an

unfamiliar claim-familiar evidence-familiar warrant in a

Reader strategies: A comprehension model text, he or she uses an argument schema to identify the

Current models of reading comprehension text (see as an argument. Meyer and Rice (1982) discovered

Ruddell, Ruddell, & Singer, 1994) depict a reader with

that readers rely heavily on structure cues, such as the

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 783

Figure 2 A comprehension model

according to three stages

Recognizing the Read text

argument stage

no?

yes?

Argument recognized.

Identifying the claim Identify as a H Ignore

and evidence stage

not match ?

Evaluate facts and examples.

match ?

Identify as E

( Claim and evidence identified.

Constructing an argument Use warrants to relate and

representation stage to relate

Evidence supports entire claim? Evidence supports different

Sparts of claim?

Argument representation constructed.

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

784 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

passage of time, and signal words, such as "in compari-

structure in the text (e.g., Meyer et al., 1980; Meyer &

son," to recognize the structure in a short text. They

Freedle,at-1984). The structure of the recall is affected by

tend particularly closely to text openings, such asthe

titles

structure of the text (Meyer & Freedle, 1984). Lorch

(Meyer & Rice, 1982). Current research in argument and Lorch (1985) also demonstrated that accurately sig-

suggests that successful readers may be able tonaling

use a text's structure in an introductory paragraph im-

Toulmin's argument structure in the same way. Kuhn proves the accuracy of the recall. Signaling in a conclud-

(1992) focused on whether people could provide ingevi-

paragraph should have an even stronger effect since

dence for their beliefs (or claims). The majority of her could use it to repair any "mistakes" in their rep-

readers

resentation. I hypothesized that competent readers use

160 participants offered plausible scenarios to support

their claims rather than actual examples or facts,warrants

appar- to link the claim and evidence they have identi-

ently unable to distinguish between claims andfied evidence.

into a coherent representation of the argument; that

However, participants in her study who had a college

their recall matches the argument's structure; and that

education typically did offer genuine evidence for their

their accuracy is affected by signaling in the concluding

claims. Readers who can distinguish these two argument

text paragraph.

parts may be able to recognize them as argument cues

in text, particularly if the claim and evidence areExtending

sig- research results to lengthy text

naled by phrases such as "I claim that..." and "EvidenceResearch thus far has used short texts, focusing on

that...." what readers do with sentences within paragraphs for

During the second stage, the reader searches thefor

most part (e.g., Hare et al., 1989). The reader who

and identifies the claim and evidence in the text. Two would comprehend a lengthy argument must be able to

types of text cues may influence this search: whether the look for text cues and perform strategies on amounts of

claim is present in the text and whether certain facts and text larger than sentences. I hypothesized that competent

examples support the claim. The claim in an argument readers notice the same cues and use the same strategies

may be analogous to the topic sentence in a paragraph. for lengthy texts of at least seven paragraphs as they

Consistently, readers are more accurate at identifying the have been found to use for paragraphs of several sen-

main idea in a short text when the topic sentence is tences.

present than when it has been omitted (Bridge, Belmore, Calfee and Chambliss (1987; Chambliss, 1994a;

Moskow, Cohen, & Mathews, 1984; Hare et al., 1989). Chambliss & Calfee, 1989, in press) have proposed a

Apparently, when no topic sentence is present, readers taxonomy to be used with texts of any length. The tax

often try to "add up" the subjects and predicates in the onomy has three wellsprings. The first comes from th

paragraph, and construct a superordinate that subsumesrhetoric. By surveying college composition books, C

everything (Kieras, 1980; Williams, 1984). Not surprising- and Chambliss (1987) identified several common pat

ly, their accuracy suffers. In this study I hypothesized terns, which they distinguished by the author's presu

that competent readers identify claim statements present purpose: to inform, to argue, or to explain (Chambliss

in written arguments. They infer absent claims. 1994a, 1994b; Chambliss & Calfee, 1989, in press). T

The search for evidence should be affected by second wellspring comes from Simon's (1981) sugge

whether particular facts and examples match the claim- that all human artifacts (including written text) can b

evidence-warrant relationship in the overall argument. characterized according to separate elements, linkag

Successful readers should be able to distinguish betweenamong the elements, and a theme to hold the design

evidence and nonevidence. Again, research on para- gether. Extending these notions to written text, Calfe

graphs is suggestive. Readers as young as sixth grade and Chambliss (1987; Chambliss, 1994a) characterize

can accurately distinguish between detail sentences that texts of any length to have elements (sentences, para-

either match or mismatch the rhetorical structure in a graphs, sections, chapters) linked (the text's structure

paragraph (Englert & Hiebert, 1984). I hypothesized that according to a theme (the author's purpose). The thi

competent readers identify evidence and distinguish it exploits the usefulness of graphics to represent compl

from nonevidence, justifying their answer by referring to relationships (Tufte, 1990). The taxonomy specifies

the structure of the argument. graphics such as topical nets, matrices, hierarchies, an

In the third stage, the reader constructs a mental Toulmin's model to depict the elements, linkages, a

representation of the author's argument whereby the theme in a text's design (Chambliss, 1994a, 1994b;

warrant links the claim to the evidence. One of the most Chambliss & Calfee, 1989).

consistent research findings to support the Meyer model Figure 1 demonstrates the approach. Each insta

is that successful readers asked to recall a text produce a of evidence in the figure represents an entire paragra

summary of important content organized to match the of details, which concludes with a sentence that exp

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 785

es the warrant. An ed theintroductory

hypothesis that successful readers construct the parag

claim. If the modelgist ofin Figure

an argument 2 familiar

by using an explicitly stated is corre

warrant to link the claim and evidence

successfully comprehends the together accord-

argumen

ognizes it as an argument,

ing to the particular configurationfinds

in the text. It varied the cl

duction, realizes that each

whether the text adhered paragraph

to a simple argument structure

instance of evidence,

or a more complex and uses

variant, whether explicit warrantthe wa

each paragraph to statements

link connected

thethe claim toparts

the evidence, whetherinto a

sentation. warrants were familiar or unfamiliar, and whether the text

conclusion summarized the argument. Readers produced

a summary recall of the argument as a measure of the

Overview of study methods mental representation they had constructed.

This study included three experiments, one for

Participants

each stage in the argument comprehension model: rec-

ognizing the argument pattern, identifying the claim and The 80 participants in the study were members of

evidence, and constructing a gist representation. Two three advanced placement English classes, one class

general types of text cues suggested by research re- from School 1 and two classes taught by the same

viewed above varied across these experiments: patternteacher from School 2. Both schools were in the same

characteristics and signaling. Measures varied by experi- middle-class suburban community of 175,000 in the San

ment depending on the particular strategies being stud- Francisco Bay area, California, USA. The classes tended

ied. The same students from three 12th-grade advanced to reflect the ethnic makeup of the schools, with approx-

placement English classes completed the comprehension imately 50% of the students belonging to minority

tasks for all three experiments. groups with Latino, Asian, or Indian surnames. School 2

Eperiment 1: Recognizing the Argument Pattern drew from a slightly higher socioeconomic area than

tested the hypothesis that competent readers would rec- School 1 and typically had higher means on the

ognize as an argument a text that followed the unfamiliar

California Assessment Program test. In the year of this

claim-familiar evidence-familiar warrant pattern and notstudy, the mean of School 1 in reading was 278, with a

otherwise. Texts were structured either as arguments or percentile ranking of 72. The mean of School 2 was 322

informational topical nets (Chambliss, 1994a; Chambliss with

& a rank of 93. Scores were on a scale of 100-400.

Calfee, in press), claims were unfamiliar or familiar, The 12 females and 14 males from School 1 had

claims came early in the text or in the conclusion, and applied for the class. Their selection was based on their

the pattern was signaled with individual signal words or standardized vocabulary and comprehension test scores,

not. Readers indicated whether they could recognize an prior grades in English, and teacher recommendations.

argument by choosing the author's purpose in writing the These separate indices were combined into a single

text (to argue or to inform), predicting the pattern they score, and the top 26 scorers in the school were chosen.

expected throughout the text (to provide evidence for the The 26 females and 28 males from School 2 had been

claim or information about the topic), and completing selected by a screening process that began in the fresh-

several measures that demonstrated whether their mental man year according to standardized vocabulary and

representation matched the argument or the information- comprehension test scores, which determined their eligi-

al pattern. bility for the freshman honors English class. Each subse-

Experiment 2: Identifying the Argument Parts tested quent year, their English teacher had decided that they

the hypothesis that successful readers would identify a should continue in the honors program, culminating in

claim explicitly stated in the text, infer a missing claim, their placement in advanced placement English for their

and identify as evidence all examples and facts that senior year. I chose these students as representative of

matched the argument pattern. This experiment em- the most successful readers produced by the public

ployed arguments exclusively and varied whether the school system.

claim was explicitly expressed in a text, whether individ- The high school English program was similar for

ual paragraphs within the text matched the argument both schools. During the 4 years, composition and litera-

pattern, and whether introductions and conclusions sig- ture instruction were typically integrated. However, in

naled the evidence accurately. Students listed the claim the 10th grade, students studied composition as an iso-

and evidence to show whether they had identified them lated discipline. During a presession, the majority of the

and explained why the author had included particular students from both schools reported to believe that they

facts and examples in the text (as evidence or not). had learned about text patterns, including argument, in

Experiment 3: Constructing the Argument's Gist test- this composition class.

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

786 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

Across the three experiments, readers were ran- EXPERIMENT 1:

domly assigned to one of two groups. Most readers

Recognizing the Argument Patter

were in a survey group where they completed paper/

Experiment 1 focused on the first stage of the

pencil tasks for the entire study. I expected survey re-

sults to provide an estimate, albeit somewhat prehension model. I designed passages and compr

superficial, of text cues and strategies used by the sion measures to identify the text cues and strategi

group

as a whole. The two teachers administered theused by competent readers recognizing the argum

survey

tasks to these students in their classrooms. A smaller pattern in a lengthy written text.

group of students met individually with either me or

one of my colleagues in another room to complete Method

think-aloud protocols, 8 students for the first two exper-

iments and 6 students for the third experiment. The

think-aloud technique has been successfully used to Participants

identify specific text cues and strategies unknowable Seventy-one students participated in this experi-

from survey data (Afflerbach & Johnston, 1986; Wade, ment, 23 from School 1 and 48 from School 2. Sixty-

Trathen, & Schraw, 1990). I expected protocol results three

to completed paper/pencil comprehension tasks.

provide an in-depth view of the cues and strategies Eight students completed think-aloud protocols.

used by students.

Design

Materials The design was a 2 (Claim Familiarity) X 2 (Clai

The passages for all three experiments came from Position) X 2 (Text Signaling) x 2 (Text Replicate) x

(Order)

an initial pool of 20 written arguments about different X 2 (Text Structure) mixed design. Text

Structure was a within subjects factor, all other factor

types of animals from natural history books and maga-

zines. As suggested by the Toulmin (1958) model, claims were between subjects, and Replicates was nested un

were superordinate statements subsuming a substantial Claim Familiarity. For the protocol group, Order was

amount of the content in the passage (e.g., Geese are counterbalanced but not a factor, and the design wa

fractionalized in half with one reader per cell.

surprisingly useful.) Evidence was at a basic level that

could be readily verified (e.g., Farmers use geese to

weed large fields.) Passages were several paragraphsMaterials

long, typically exceeding 1,200 words. Texts. The Claim Familiarity and Text Replicate fac-

In a presession, participants provided examplestors required four base texts with familiar evidence and

for claims and rated the truth of claims, evidence, andwarrants, two with unfamiliar and two with familiar

warrants from the text pool. Since warrants are the un-claims. The Text Structure factor required that each base

derlying premise, they often are not explicitly statedtext

in be rewritten to have two versions differing accord-

written arguments. Therefore, I inferred them by con- ing to structural pattern: an argument with a claim, evi-

structing generalizations that subsumed both the claim dence, and warrants (Figure 3) and a topical net (Figure

and evidence analogous to major premises in syllogisms 4). The four argument versions included only content

(e.g., Birds that farmers can use to weed large fields consistent

are with the argument diagram. The four topical

net versions included all other information from the orig-

surprisingly useful.) If the majority of participants pre-

dicted that they could give no examples for a claiminal selection. Since passages differed in the amount of

and

had no idea whether it was true, I judged the claim to this ancillary information, I added content from other

be unfamiliar (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). I judged ev- sources to control for length.

idence and warrants to be familiar if the majority of par- Claim Placement and Signaling were the last two

ticipants rated them as true or probably true. Results text factors. The claim appeared in either the introduc-

tion

from the pretest allowed me to manipulate the familiari- or conclusion of the text. Versions either did or did

ty of claims, evidence, and warrants across the three not signal the overall text structure and its parts. Phrases

experiments. such as, "This evidence points to an important truth

The study required 14 base texts. I rewrote the about topic," and "I will share information about topic",

original passages to match the experimental designs.signaled

In the text pattern. Other phrases, "For example,

we have evidence that ," "I propose that claim," and

addition, rewrites shared two features: introductory and

concluding paragraphs that signaled the structure, and"Biologists inform us that " signaled pattern parts

paragraph topic sentences. (Shopen & Williams, 1981; Vande Kopple, 1985).

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 787

Figure 3 The introductory paragraph

The introductory paragraph tha

In many obvious respects elephants are not one

whether we compare body shape and size, nose

care for both very young and very old membe

elephants frequently behave like people do.

The argument diagram that or

Evidence Warrant Claim

Elephants figure out how to

avoid being shocked by an

electric fence.

Figuring out solutions to new

situations is a human behavior.

Two elephants court and "go

steady."

Courting and going steady are

human behaviors.

A mother elephant disciplines her

baby for going in deep water.

Disciplining the young for

misbehaving is a human behavior.

Elephants frequently

behave like people.

A mother elephant mourns her

Mourning the dead is a human

dead baby and buries it. behavior.

Taking care of the old is a human

Young elephants take care of an behavior.

old elephant until he dies.

Remembering kindness is a

human behavior.

A young elephant remembers the

kindness of a human helper for a

long time.

Rewrites based on these two factors resulted in 32 text ments relating the instance of evidence to the claim (see

versions. Figure 3). For topical net versions, one of the instances

All versions were approximately three pages of sin-of evidence was included as a subtopic to provide the

gle-spaced typing. Each instance of evidence or subtopic

same amount of elaboration for the claim as paragraph

in the diagram was a paragraph long. Paragraphs in ar-

topic sentences had. Both argument and topical net ver-

gument versions concluded with explicit warrant state- sions included two superordinate statements: the claim -

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

788 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

Figure 4 The introductory paragraph and topical net diagram for the informational top

version about elephants

The introductory paragraph that summarizes the entire text

In many obvious respects elephants are not one whit like people. The elephant trunk is their most distinctive fe

course. There are actually two types of elephants, Asian and African, which, while different in important respec

acteristics, such as eating and sleeping habits, skin care needs, and swimming ability. Both types are also surpris

their feet. Furthermore, despite the obvious physical differences, elephants of both types frequently behave lik

The topical net diagram that organizes the entire text

Trunk Two types

characteristics of elephants

Eating

Swimming habits

Elephants

ability

Reasoning Skin

ability care

Dexterity

and an "innocuous" generalization that waspurpose not elaborat-

(to present information about the topic or to

ed in the body of the text. For the two elephant support a point). The second and third items assessed

texts,

this generalization was, "In many obvious respects, ele- of the representations that readers had

the configuration

phants are not one whit like people." The generalization constructed for the two types of patterns. Item 2 instruct-

was included as a distractor for the measurement instru- ed participants to summarize the text in a single sen-

ment described below. tence. Item 3 presented participants with 10 sentences

To prompt protocol readers to think aloud, I from the text: the innocuous generalization, the claim, 4

placed small red dots at the end of each paragraph of paragraph topic sentences, and 4 detail sentences. In-

their text copies. Otherwise, their versions were identicalstructions told readers to distribute 100 points among the

to those used for the survey task. 10 sentences according to how important each sentence

The pattern recognition (PR) measure. The PR mea- would be in summarizing the text.

sure assessed the effect of text pattern type and signaling Because of the claim-evidence-warrant structure in

on the pattern that readers recognized. The paper/pencil an argument, readers should be able to use the claim as

version contained four items. The first item measured a single sentence to summarize the text if they have rep-

whether readers could distinguish the argument and top- resented it as an argument. Likewise, they should assign

ical net patterns, asking them to identify the author's a much larger share of the 100 points to the claim than

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 789

Table 1 A sample of one-sentence sum

how closely summaries matched the

Rating

One-sentence summary (2-0)

Claim: Elephants frequently behav

"* Elephants behave in a manner similar to humans. 2

"* Elephants are similar to people in many aspects because of the way

yet they're very different in their physical needs and features.

"* Elephants have many interesting and unusual characteristics. 0

Claim: Geese are surprisingly useful animals.

"* Geese are useful animals in a very broad variety of respects. 2

"* Geese can be useful to humans in many ways. 2

"* (No summary of the argument or topical net versions of "Ge

"* Geese are not ducks: they are intelligent and clever, have

by domestication, and are excellent guard animals.

Claim: Birds build an astonishing variety of nests.

"* Despite the fact that bird nests are all used for the same

"* This tells the purpose, construction, and variety of bird nests. 1

"* This passage gives us facts about birds and their nests. 0

Claim: Leopards are very dangerous predators.

"* Leopards, because of their many impressive characteristics, are truly dangerous predators. 2

"* The leopard is a beautiful, but dangerous animal which rarely attacks man. 1

"* The author gives information about leopards. 0

to the other sentences from the

measures. text,

Because including

of the Order factor, half of thethe

pack- in-

nocuous generalization. A etstopical net

presented the text has

with an a structure

argument differentfirst.

tern, represented by a topic that

Instructions subsumes

at the top of each passage a series

instructed readersof

subtopics. If readers have accurately

to read for the author'srepresented

message without worryingthe about in

details. The

formational text, they should useend of each passage directedother

something readers to than

the claim to summarize it and should distribute the 100 complete the PR measure without looking back at the

points approximately equally across the topic sentences text. Packets for the protocols omitted the PR measures

in the text, one of which is the claim in the argument since the index cards served the same purpose.

version. Item 4 asked participants to explain their ratio-

nale for assigning points. If their representation matched Procedure

the text pattern, I expected their rationale to refer to the Survey packets were stacked in random order for

claim and its evidence for the argument and subtopics each class. The classroom teachers followed the same

for the informational text. written instructions, distributing the packets face down

To measure pattern recognition for the protocol and giving readers 15 minutes to read and complete the

group, large 5" x 8" index cards directed readers to PR measure for each text. Both teachers were unaware

choose the author's purpose, predict what they expected of the purpose of the experiment and the experimental

would come next in the passage, and justify their an- conditions.

swers. Readers who had recognized an argument should Simultaneously, the protocol participants met indi-

choose the "argue" purpose, predict that they would vidually with me or one of my colleagues in an adjoin-

read about evidence, and point to the claim-evidence- ing classroom. We instructed each participant to read for

warrant structure in the text as justification. Those who the author's message rather than details and to pause at

had recognized an informational pattern should choose red dots to answer the questions on the index card. After

an "inform" purpose, predict that they would be reading completing each text, readers wrote a free recall to

information about the topic, and point to the subtopics demonstrate whether their representation of the text

to justify their responses. matched either an argument or an informational pattern.

Text packets. Packets for survey tasks combined Participants were given unlimited time to complete all

two passages differing only in text structure with two PR tasks within the constraints of a 50-minute period.

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

790 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

Table 2 Means for Claim Position, Text Structure, and Text Replicate for three dependent mea

recognizing the argument pattern

Author's purpose Summary Claim rating

(1-2) (0-2) (0-100)

Between-subjects facto

Claim Position

First (N= 32) 1.56 (.50) .89 (.89) 22.17 (13.39)

Last (N= 31) 1.48 (.50) 1.26 (.92) 23.34 (17.25)

Text Replicate"

Unfamiliar Claim

Elephants/geese (N= 17) 1.56 (.50) 1.00 (.89) 23.94 (14.94)

Geese/elephants (N= 18) 1.53 (.51) 1.08 (.97) 20.05 (8.92)

Familiar Claim

Nests/leopards (N= 14) 1.41 (.50) 1.04 (.94) 23.48 (18.45)

Leopards/nests (N= 14) 1.59 (.50) 1.11 (.93) 24.15 (19.14)

Within-subjects factor

Text Structure

Argument (N= 63) 1.92 (.27) 1.76 (.53) 28.29 (17.33)

Informational (N= 63) 1.11 (.32) .33 (.62) 17.05 (10.31)

Note. Italics denotes p<.05; both italic and boldfaced p<.001.

a The first text in each pairing was structured as an argument; the second w

Assigning survey scores cause its subject and predicate subordinated the prepon-

Higher scores for three derance

of of thecontentmeasures

in the recall. If the recall had such a

collected

from the surveys indicated claim,

that

it was diagrammed

participants as having an argument

hadstruc- recog

nized the argument pattern. ture.For

Because the

text structure

first was item,

expected to "Suppor

have a

powerful influence

ing a point" received a 2; "Giving on pattern recognition and

information" a because

1. A

one-sentence summary received

the analysis procedure

a 2 had

for

been developed

a close for this

para-

study,

phrase of the claim, a 1 for antwo analysts

imperfectcompleted diagrams for all recalls.

paraphrase th

included information from Judgments

the matched

claim's for 93% subject

of the analyses (15

and recalls),

pred

with consensus

cate, but (a) used terms that were reachedeitheron the remaining

more recall. general

specific than the terms in the claim or (b) embedded th

claim as either a dependent clause Results or as one of a ser

of equally important clauses. All other answers recei

a 0. Scoring for this second item Regardlessrequired

of task or measure,

a high

Text Structure

degre

of inference. Two raters independently strongly and consistently affected

scored readers'

allresponses.

re- N

sponses. Their judgments matched other factor had for

either strong

92% or of

consistent

the effects.

score Res

with consensus easily reached for the two on

typesthe remaining

of tasks scor

are reported separately.

Table 1 presents a sample of 12 responses and their r

ings. The third item was Written survey tasks

quantitative and needed no

scoring. Responses to the fourth Table 2 displays

item large main effect

were means for the

categorical,

and I analyzed them separately. three measures.

TheRow headings in consistent

results, Table 2 show the fa

with the other three measures, tors; column are not

headings detailed

show the measures.in this

The table

report. also indicates significance levels resulting from ANOVA

tests conducted for each measure. Consistently low to

modest correlations among measures indicated the ap

Analyzing protocols propriateness of using univariate rather than multivari

Analyses for protocol responses focused on an- analyses. The cells in the experimental design had un

swers consistent with recognizing an argument pattern. equal sizes because of a mixup in distributing the pac

The analysis of the free recalls began with a search for a ets and failure of some students to return completed

superordinate statement that could serve as a claim be packets.

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 791

Means for texts with general information

an about birds' nests. Next I expect to

argument st

consistently higher read about how birds

than make adaptations.

means for tex

tional structure regardless of measure.

Throughout both types of texts, participants tended

tured as arguments rather than topical

to reaffirm their initial decision. While reading an argu-

tended to choose an argument purpo

ment text, another reader explained,

379.17, p<.001, MSE = .06, use the cla

the text, F(1,42) = The purpose is to provide support

235.66, for a point, and I canMS

p<.001,

the claim as more tell because the paragraph supports

important the author's point

than topiof

view by giving an example. I think this is good support;

tails, F(1,42) = 28.47, p<.001, MSE =

Other differences were either small or inconsistent because the reasoning example shows elephants acting

similarly to people [the argument's claim].

across measures. Claim Position affected the summary

score. This result may reflect a recency rather than a Participants responded differently when they could

comprehension effect. Students who had just read the not locate the claim/evidence relationship. As they read

claim in the concluding paragraph were more likely to texts structured as topical nets, readers would explain,

use it to summarize the text than those who had read it

The purpose is to provide information. The text doesn't

in the introduction, F(1,42) = 15.76, p<.001, MSE = .31. state a point that it's supporting.... This text is not arguing

Both Text Replicates, F(2,42) = 3.22, p<.05, MSE = .09 a point. It's just giving you stuff.

and an interaction between Text Structure and Text

Signaling, F(1,42) = 8.18, p<.01, MSE = .06, affected the Readers' responses differed depending on the pat-

author's purpose score. In the first case, readers tended tern in the text. For texts structured as arguments they

to choose an informational purpose for a text about bird identified the "support" purpose, pointed to the claim/

nests regardless of text structure. Consequently, the pair evidence relationship as justification, and predicted addi-

of replicates where nests had an argument structure re- tional evidence, the precise pattern I expected. For the

ceived a lower score than the other pairings. The inter- topical net they chose an "inform" purpose, pointed to

action resulted from signaling increasing the difference signaling, facts, or the absence of argument parts as justi-

in scores for the two text structures. All students chose fication, and predicted they would read more informa-

tion

an argument purpose when a text was both structured

and signaled as an argument (M = 2.00) while they tend- As for the written comprehension tasks, signaling

ed to choose an informational purpose for a text both and claim placement had no consistent effects. Although

structured and signaled accordingly (M = 1.06). These readers responded no differently when signaling was ab-

differences were not as great for texts without signaling sent, they sometimes referred to its presence. Placing the

(M = 1.82 and M = 1.13). Neither of these effects oc- claim at the end of the text also had no effect. Readers

curred for the other two measures, however. had inferred it by the close of the second paragraph:

Protocols. The protocol data corroborated and ex- The author is starting to make a point about the fact that

tended the data from the surveys. Text Structure was the the leopard is a dangerous predator. Next I will be read-

one text characteristic consistently influencing how read- ing more support about the thesis, the point.

ers responded. Immediately upon recognizing the

This reader had correctly induced the claim from the

claim/evidence structure in a text, they would identify it

summary of all the evidence she read in the introduc-

as an argument. Failing to find that structure, readers

tion, the elaboration of the first instance of evidence,

would identify the text as informational. The following

and the warrant, which linked this evidence to the miss-

examples illustrate the types of responses made by par-

ing claim and occurred as the concluding sentence of

ticipants. Following the first paragraph of a text with an

the paragraph ("Surely any animal that can so cleverly

argument structure, one reader explained,

trick its prey is a dangerous predator.").

The author's purpose is to present support for a point. I

Free recalls supported the protocol results. Figure 5

can see evidence for the point in this introductory para-

depicts recalls of the argument and topical net versions

graph. I expect that next the author will give examples of

about elephants. The top panel shows the argument pat-

how geese help [the text's claim]. The thesis makes you

tern and the recall on which it was based. The reader

expect you'll get more reasons.

had accurately recalled both claim and evidence. He also

After reading the introductory paragraph for the included appropriate metadiscourse (talk about talk) in

topical net, the same reader answered, his introduction.

The author's purpose is to give information about birds' Hugh O'Brien [sic], the author of the essay, proposes that

nests. This paragraph was an introduction with lots of elephants are similar to humans in the way in which they

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

792 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

Figure 5 Verbatim recalls and text diagrams of two readers after reading either the argument

about elephants

Argument text

Evidence Warrant Claim

Hugh O'Brien (sic), the author of the essay, proposes

that elephants are similar to humans in the way

Twoin whichelephants showed

affection.

they behave. In the introductory paragraph, he stated

that elephants do not appear to be like humans; Elephants

however, they do act like humans. showed definite

human behavior.

His examples to support his thesis included specific

instances in which elephants showed definite Elephant

human be- mother

havior. One of the examples included two elephants

punished naughty cub.

showing affection to one another.

Also, elephants care for each other the way humans Elephants care Elephants are

do. The author stated several examples in which ele- similar to hu-

for each other

phants demonstrated human traits. A mother elephant, like humans do. mans in the way

Young elephants in which they

after saving her cub from drowning, waited to see if it Elephants

protect old. behave.

was all right before she punished him. Young elephants demonstrated

have been seen protecting the old and weak elephants human traits.

of the herd. Another example was when a mother ele-

phant was mourning after her dead newborn cub. She

walked around without eating and very temperamental

and eventually buried it. Mother elephant

mourned dead cub.

Elephants not only act like humans but they can rea- Elephants

son like humans as well. The author stated an occurance reason like

humans.

in the jungle where an expedition put up electric fences

to prevent the elephants from entering. The elephants "Elephants figured out

found out that when the lights were on, the fence was that their tusks did not

not electrified and that their tusks did not conduct elec- conduct electricity.

tricity.

Informational text

Body hair

Skin care Trunk Tusks Uses

What I remember from this article was that there are

two types of elephants, the African and the Asian. The

elephants are different, but have a few things in com-

mon, such as skin care, and of course, a trunk. The ele-

phant's trunk is used for eating, drinking, breathing,

Similarities Differences

smelling, and self defense. Elephants also take very

good care of their skin, since it is tough and leathery.

The differences between the Asian and African ele-

phants are the tusk size, amount of hair growth, and

also the Asian elephant is usually the one seen in circus

Two types

shows, etc. The elephants have a big appetite and eat a

lot also. Elephants are also very good swimmers. They

are also very smart, and can reason well. Elephants are

also light on their feet, and cannot (will not) really

crush anything.

Elephants

Light on

Appetite feet

Good swimmers

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 793

Figure 6 A diagram of the argument st

Evidence Warrant Claim Ancillary content

Ant species tend aphids to be

able to collect and drink the

Different ant-castes are partly

liquid they produce.

determined by the amount of

kohlrabies fed to the larvae and

partly determined by whether the

larvae develop from fertilized

Fierce army ants move about in eggs.

a compact herd, attacking all

animals in their path.

Any animal that maintains

herds, invades and conquers

Farmer ants cultivate crops. new lands, cultivates crops,

weaves "fabric," and captures Ant tribes pursue occupations

slaves is pursuing occupations startlingly like humankind's.

startlingly like humankind's.

Weaver ants construct cradles

for their larvae.

Slave-making ants capture oth-

er ants to do their work for

them.

behave...His examples to support his thesis included spe- EXPERIMENT 2:

cific instances in which elephants showed definite human

behavior. Identifying the argument parts

The bottom panel of Figure 5 displays the recall The second experiment focused on the secon

and diagram from another participant who read the topi-

stage of the comprehension model. Both texts an

cal net version about elephants. She recounted what she

sures were designed to identify the text cues and s

remembered from the text she had read as topics and

gies used by competent readers to find the claim

subtopics rather than as a claim and evidence. These dif-

ferences in recalls were typical. evidence in a lengthy written argument.

Conclusion

Method

Results suggest that good readers use the presence

Participants

or absence of a claim-evidence-warrant relationship to

recognize a written argument and distinguish it from Sixty

an participants completed written tasks; eight

informational topical net. Whether a text had signaling,

completed protocols.

claims were unfamiliar, or claims were placed in intro-

ductions had virtually no effect on reader performance.

Design

For texts with an argument structure, readers chose an

The design was a 2 (Order) X 2 (Signaling) x 2

"argue" purpose, expected to find argument parts in the

(Text

text, summarized it with the claim, and structured their Replicate) x 2 (Claim Presence) X 6 (Paragrap

recalls as arguments. Their answers followed quitemixed design with Order, Signaling, and Text Replic

a dif-

the between-subjects factors, Claim Presence a within-

ferent pattern for informational texts where the claim-

evidence-warrant relationship was missing. subjects factor, and Paragraphs a within-text factor.

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

794 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

Table 3 A sample of claim statements that readers constructed after reading arguments with explicit a

claims and the ratings assigned to the statements according to how closely they matched the a

claim

Rating

Claim statement (3-0)

Claim: The coyote is par

"* Coyotes take the best advantage of their environment. 3

"* Coyotes are very adept and can adapt to almost any environment well. 2

"* Coyotes, contrary to the saying that they are inferior members of the wolf family, ar

they have a better chance to survive.

"* Many people tend to overlook the remarkable qualitites and habits that coyotes possess. O

Claim: Ant tribes pursue occupations startlingly like humankind's.

"* Ants have occupations amazingly similar to mans [sic], (both past and present). 3

"* Ants, in their duties and roles, are much like humans in their respective roles. 2

"* Ants act very much like "civilized" humans do. 1

"* Ants are industrious and society oriented. 0

Materials Procedure

Texts. Two passages from the original pool of 20 Participants completed the two types of tasks as in

texts were used for this experiment, both with unfamiliarthe first experiment with one exception. They were told

claims, familiar evidence, and familiar warrants. Repli- that both passages had been written to support a point.

cates were prepared comparably to the first experiment,

with three exceptions. All versions had an argument

Assigning survey scores

structure. According to the Paragraphs factor, one para-

The author's claim scores distinguished among dif-

graph in each text was ancillary to the relationship in the

claim, related to it topically only. A summary warrant inferent degrees of accuracy. For each claim, I identified

the concluding paragraph related the evidence to the two concepts that each instance of evidence in the argu

claim instead of individual warrants at the end of each ment exemplified ("taking advantage" and "environment"

paragraph. Figure 6 depicts the resulting structure for for the argument about coyotes; "occupations" and "lik

one of the texts. humankind's" for the argument about ants). A claim

These structures formed the basis for the four repli- statement that related both concepts received a 3. If both

cates. Because of the Claim Presence factor, introduc- concepts were present, but the meaning of one or both

tions either did or did not contain the argument's claim. was slightly different, the statement received a 2 (e.g.,

The Signaling factor required that introductions and con- "situation" for "environment"; "roles" for "occupations").

clusions either summarized the argument accurately by A statement with only one of the concepts received a 1.

including only content from the evidence paragraphs or Anything else received a 0. Because scoring of claim

summarized the entire passage by including content statements involved a high degree of inference, three

from the ancillary paragraph as well. raters scored the responses independently. On 98% of

School 1 participants, completing the tasks first, the responses, two of the three raters assigned identical

seemed consistently to misinterpret the meaning of the scores. Raters reached consensus on the remaining rat-

claim slightly for one of the passages. Consequently, I ings. Table 3 lists a sample of claim statements and their

reworded the title and rewrote several paragraph topic accompanying scores. Evidence list responses received

sentences for students from School 2.

one point for each of the six text paragraphs from which

The Identification Measure (IM). The IM asked students included at least one piece of information.

readers completing written surveys to (a) write the au-

thor's point and (b) summarize in a single sentence each

of the five pieces of support in the argument. Prompts Analyzing protocols

asked students completing protocols to explain why they Protocol analyses focused on how the presence or

thought the author had included the paragraph they had absence of the claim affected readers' identification of

just read, share any thoughts they had while reading, the author's claim throughout the text, particular text

state the author's point for the entire passage, and justify characteristics that they gave as rationale for their an-

their answer. swers, and how they handled the ancillary paragraph.

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Constructing argument gist 795

Table 4 Means for Signaling, Claim P

Experiment 2: identifying the argu

Author's claim Support list

(0-3) (0-1)

Between-subje

Signaling

Exact (N = 29) 1.93 (.87) (N = 348) .77 (.42)

Ancillary (N= 31) 1.22 (.89) (N = 372) .70 (.46)

Within-subjects factor

Claim Presence

Present (N = 60) 1.80 (.92) (N= 720) .75 (.43)

Absent (N= 60) 1.33 (.93) (N= 720) .72 (.45)

Within-text factor

Paragraphs

Evidenceb (N= 600) .79 (.41)

Ancillary (N= 120) .47 (.50)

Note. Italics denotes p<.05; boldfaced, p<.01; bo

a Within-text factors were measured only by the

b The mean for evidence has been computed a

Results paragraphs was significant, F(1,31) = 11.67, p<.001, MSE

= .24. As hypothesized, participants were more likely to

Whether introductions and conclusions signaled

list evidence as support and leave ancillary content off

the argument accurately, claim statements were present

the list when the argument was summarized accurately in

or absent, and content in paragraphs was relevant or an-

the introduction and conclusion than otherwise.

cillary influenced the claim and evidence that readers Claim Presence affected the author's claim score, as

identified in the argument. expected, F(1,31) = 7.71, p<.01, MSE = .54. Readers re-

sponded more accurately when the claim was present

Written survey tasks than absent. An interaction with school indicated that the

Table 4 displays the means for large main effects

effect was more evident for School 1 than School 2 par-

for each of the two measures and the significance levelsF(1,31) = 7.71, p<.01, MSE = .54. School 2

ticipants,

from analyses of variance. Consistently modest toreaders

low were equally accurate at stating the claim regard-

correlations among the two measures indicated lesstheof ap-

claim presence.

propriateness of univariate rather than multivariate analy-

The contrast between evidence and ancillary con-

ses. An ANOVA for each measure was conducted on a

tent had an effect on the evidence list, [(1,31) = 34.16,

subset of the data. To test the effect of slightly different

p<.001, MSE = .24. Readers were almost twice as likely

text versions for each of the schools, I added School to as list

a evidence as they were to list ancillary content. A

factor. Since almost twice as many students came from quadratic contrast conducted on the five evidence para-

School 2, I eliminated School 2 data until the design graphs

was suggested that readers were somewhat more like-

complete with three students per cell and ran the ly to list evidence from the beginning and end of the

ANOVA tests on a subset of the data.

text than the middle, perhaps reflecting primacy and re-

Signaling in introductions and conclusions affectedcency memory effects, F(1,31) = 6.13, P<.05, MSE = .11.

both measures. Participants were more likely to produceSince ancillary content appeared as the fifth paragraph

an accurate statement of the author's claim when the in-

out of eight in both texts, some readers may have left

troductory and concluding paragraphs summarized only ancillary content off the list because they forgot it rather

the argument, F(1,31) = 19.08, p<.001, MSE = .83, an out-than rejected it as support.

come I had not anticipated. They also listed more items

overall on the evidence list when introductions and con- Protocol tasks

clusions summarized the argument accurately, F(1,31) = Protocols matched results from the written surveys.

4.40, p<.05, MSE = .13. The interaction between Signaling

Most participants recognized the claim in the argument

and an orthogonal contrast of evidence with ancillary and identified as evidence paragraphs that supported the

This content downloaded from

200.75.19.153 on Sun, 22 Aug 2021 21:55:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

796 READING RESEARCH QUARTERLY October/November/December 1995 30/4

claim while rejecting as evidence paragraphs only topi- realized how all those examples fit in. [The

cally related. When the claim was missing, some readers author] compared humans and ants."

quickly inferred it, apparently from patterns they recog-

Other participants were willing to accept that texts

nized in the evidence. Others frequently changed their

with missing claims were arguments. They readily in-

minds about the claim as they successively read the

duced claims, which changed after each paragraph. In

paragraphs in the text. They seemed particularly influ-

addition, they tended to accept ancillary content as evi-

enced by the ancillary paragraph, broadening the claim

dence. The accuracy of their answers was affected by

to incorporate it rather than realizing that it did not fit

both the absence of the claim and the presence of

the rest of the argument. Two readers seemed unable to

nonevidentiary information.

infer a missing claim.

In the first example, the reader found the claim in Introduction: "I can't tell the point yet."

Paragraph 2: "No matter what the environment, the coy-

the introduction, stated it as the author's point through-

out the text, and accurately distinguished evidence from ote tries to solve problems. It will find a

ancillary content. way to live."

Paragraph 3: "The coyote will eat no matter what the

Introduction: "The point is that ants' occupations are go- cost; it will take advantage of every oppor-

ing to be like humans. It says it right here." tunity."

Paragraph 2: "It's still the same. Ants are like humans." Paragraph 4: "The coyote is smart. He will make the best

(Note that "occupations" dropped out, a

of any situation where he can get a free

change that occurred frequently among

meal. He always thinks before he acts."

readers.)

Ancillary: "The same point. Coyotes make do with

Paragraph 3: "The same point. Ants have human-like

what they have. Also, that they are smart....

qualities."

The author could be comparing them to hu-

Paragraph 4: "Same [point]. Ants are like humans."

mans. I'm not really sure. But their children

Ancillary: "Same [point]. This paragraph is not good

are important to them-a lot like humans.

support. Humans don't do this."

They make do with what they have, just

Paragraph 6: "Same [point]. Ants are human-like. Now

like humans. Anyone will take a good deal.

he's back on track to support the point."

Humans do that too."

Paragraph 7: "Ants are human-like."

This reader's statement of the author's claim changed

Readers intent on looking for a claim in the text

throughout the passage. Note particularly her last re-

were thrown by versions that did not explicitly state it.

sponse. Upon reading the ancillary paragraph, she re-

After reading the introduction, one reader explained,

viewed what she had read about the coyote thus far and

Introduction: "This passage will just give information.

seemed to be searching for one generalization to subsume

There is no opinion in the first paragraph."

even the ancillary information about how coyotes parent.

He was unable to identify a claim until after reading the Other readers were more accurate at inducing the

warrant at the end of the passage, which specifically re- claim from the evidence, and consequently less strongly

lated the evidence to the claim. influenced by the ancillary paragraph.

Paragraph 2: "No opinion yet." Introduction: "The coyote can survive the environment. It

Paragraph 3: "Not that I can tell." is a fighter. It does a lot of adaptive stuff. I

Paragraph 4: "Just an essay on ants." can tell [that this is the point] because this

Ancillary: "It's an informative research paper on ants." introductory paragraph kept saying how

Paragraph 6: "No opinion. Just about how ants make they got food, and examples of how it