Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effects of COVID-19 On Parkinson 'S Disease Clinical Features: A Community-Based Case-Control Study

Effects of COVID-19 On Parkinson 'S Disease Clinical Features: A Community-Based Case-Control Study

Uploaded by

JosmiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effects of COVID-19 On Parkinson 'S Disease Clinical Features: A Community-Based Case-Control Study

Effects of COVID-19 On Parkinson 'S Disease Clinical Features: A Community-Based Case-Control Study

Uploaded by

JosmiCopyright:

Available Formats

BRIEF REPORT

Effects of COVID-19 on

Parkinson’s Disease Clinical

Features: A Community-Based Since the first patient was diagnosed with coronavirus

Case-Control Study disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Lombardy, on February

20, 2020, Italy has become the third most affected coun-

try (>215,000 cases and 30,000 deaths) in the world.1

Roberto Cilia, MD,1* Salvatore Bonvegna, MD,1 COVID-19 neurotropic properties may underlie a wors-

Giulia Straccia, MD,1,2 Nico Golfrè Andreasi, MD,1 ening of chronic neurological diseases, such as

Antonio E. Elia, MD, PhD,1 Luigi M. Romito, MD, PhD,1

Parkinson’s disease (PD). COVID-19 may worsen PD by

Grazia Devigili, MD, PhD,1 Emanuele Cereda, MD, PhD,3

a number of mechanisms,2-4 including pharmacodynam-

and Roberto Eleopra, MD1

ics changes (eg, reciprocal interactions between the dopa-

minergic and renin-angiotensin systems in the substantia

1

Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Department

nigra and striatum5) as well as systemic inflammatory

of Clinical Neurosciences, Parkinson and Movement Disorders Unit, responses.6-9 Patients with PD are frailer than the general

Milan, Italy 2Department of Medical Sciences and Advanced population because of disease-related factors and age-

Surgery, University of Campania, Naples, Italy 3Clinical Nutrition related comorbidities.2-4,10,11 A higher COVID-19 mor-

and Dietetics Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, tality rate has been described in advanced PD patients in

Pavia, Italy

association with older age and longer disease duration.12

Our primary objective was to investigate the effects of

COVID-19 on motor and nonmotor symptoms in a

A B S T R A C T : The impact of coronavirus disease community-based PD cohort. In addition, we explored

2019 (COVID-19) on clinical features of Parkinson’s whether older age and longer disease duration represen-

disease (PD) has been poorly characterized so far. Of ted risk factors for developing symptomatic COVID-19.

141 PD patients resident in Lombardy, we found

12 COVID-19 cases (8.5%), whose mean age and dis-

ease duration (65.5 and 6.3 years, respectively) were Materials and Methods

similar to controls. Changes in clinical features in the

period January 2020 to April 2020 were compared with In the present observational, community-based, case-

those of 36 PD controls matched for sex, age, and dis- control study, we investigated the demographic and

ease duration using the clinical impression of severity clinical features in a cohort of patients with idiopathic

index for PD, the Movement Disorders Society Unified PD13 and COVID-19 when compared with controls

PD Rating Scale Parts II and IV, and the nonmotor

with PD between the preoutbreak period in Italy

symptoms scale. Motor and nonmotor symptoms sig-

(January 1, 2020) and the end of lockdown restrictions

nificantly worsened in the COVID-19 group, requiring

therapy adjustment in one third of cases. Clinical (May 4, 2020). A 3-month period was chosen to mini-

deterioration was explained by both infection-related mize the effect of PD progression on the change in clini-

mechanisms and impaired pharmacokinetics of dopa- cal features and the recall bias. The diagnosis of

minergic therapy. Urinary issues and fatigue were the COVID-19 was performed according to the clinical and

most prominent nonmotor issues. Cognitive functions laboratory criteria for probable and confirmed cases

were marginally involved, whereas none experienced released by the World Health Organization criteria on

autonomic failure. © 2020 International Parkinson and March 20, 2020.14 In symptomatic cases fulfilling

Movement Disorder Society criteria for “probable case,”14,15 we included only

patients with close and protracted contacts (ie, care-

-*Correspondence

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -to:- - Dr.

- - - Roberto

- - - - - - -Cilia,

- - - - Fondazione

- - - - - - - - - -IRCCS

- - - - - -Istituto

--------- givers) with laboratory-confirmed cases.

Neurologico Carlo Besta, Parkinson and Movement Disorders Unit, via Out of the 1092 records obtained by searching the Besta

Celoria 11, 20133, Milan, Italy; E-mail: roberto.cilia@istituto-besta.it Institute clinical software for patients fulfilling the follow-

Salvatore Bonvegna, Giulia Straccia, and Nico Golfrè Andreasi contrib- ing criteria: (1) International Classification of Diseases,

uted equally to this article. Ninth Revision, clinical modification code for parkinson-

Relevant conflicts of interests/financial disclosures: Nothing to ism 332.0; (2) resident in the Lombardy region, northern

report.

Italy (which is by far the most affected area [>80.000

Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 21 May 2020 cases] with the highest case fatality [>15.000 deaths] in

Published online 11 June 2020 in Wiley Online Library Italy as of May 11, 2020)16; and (3) visited at least once

(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/mds.28170 by a neurologist from January 1, 2019 to December

Movement Disorders, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2020 1287

C I L I A E T A L

31, 2019, we performed a random selection of 150 PD for to the remote assessment and collection of clinical data, as

subsequent remote interview by a neurologist experienced approved by the local ethics committee.

in movement disorders (by video consultation or tele- Of a total of 141 patients who agreed to be inter-

phone),2,17,18 which was performed between April 15 and viewed, 12 (8.5%) were affected by COVID-19.14

May 4, 2020. Signed informed consent was obtained prior Compared with the overall cohort of 129 control

TABLE 1. Characteristics of the study population

Variable Cases, N = 12 Controls, N = 36 P Value*

General features

Male sex, N (%) 5 (41.7) 15 (41.7) 1.00

Age, y, mean (SD) 65.5 (8.9) 66.3 (8.1) 0.78

Current smoking, N (%) 0 (0.0) 3 (8.3) 0.56

Past smoking, N (%) 5 (41.7) 10 (27.8) 0.48

Frequency of smoking, cigarettes/day, N (%) 10.0 (8.7) 9.1 (7.3) 0.82

Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) 25.1 (3.8) 25.5 (3.8) 0.77

Body weight, kg, mean (SD) 67.0 (11.5) 71.3 (14.5) 0.36

Seasonal vaccinations in 2019, total N (%) 3 (25.0) 9 (25.0) 1.00

Anti-H1N1, N (%) 3 (25.0) 9 (25.0) 1.00

Antipneumococcus, N (%) 1 (8.3) 2 (5.5) 1.00

PD-related featuresa

Age at PD onset, y, mean (SD) 59.0 (8.1) 60.4 (7.8) 0.58

Tremor-dominant phenotype, N (%) 6 (50) 18 (50) 1.00

Disease duration, y, mean (SD) 6.3 (3.6) 6.1 (2.9) 0.79

Hoehn and Yahr stage, mean (SD) 1.8 (0.7) 1.8 (0.6) 0.95

Dementia, N (%) 0 (0.0) 3 (8.3) 0.56

Therapy

Levodopa, N (%) 10 (83.3) 28 (77.8) 1.00

Levodopa dose, mg/day, mean (SD) 400.0 (119.3) 433.6 (227.1) 0.09

DA, N (%) 9 (75.0) 23 (63.9) 0.73

iMAO-B, N (%) 6 (50.0) 16 (44.4) 0.75

iCOMT, N (%) 0 (0.0) 4 (11.1) 0.56

Amantadine, N (%) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1.00

Advanced-stage invasive therapies, N (%)b 1 (8.3) 1 (2.8) 0.44

Total LEDD, mg/day, mean (SD) 571 (517) 487 (327) 0.52

Therapy adjustment during the study period, N (%) 4 (33.3) 2 (5.5) 0.028

Risk factors for COVID-19

Contact with confirmed or suspect COVID-19, total N (%)c 8 (66.7) 4 (11.1) <0.001

Confirmed COVID-19, N (%) 6 (50.0) 0 (0.0) <0.001

Suspect COVID-19, N (%) 2 (16.7) 4 (11.1) 0.63

Comorbidities

Any 9 (75) 24 (66.7) 0.73

COPD 1 (8.3) 4 (11.1) 1.00

Hypertension, N (%) 4 (33.3) 16 (44.4) 0.74

Obesity, N (%) 1 (8.3) 2 (5.5) 1.00

Diabetes mellitus, N (%) 0 (0.0) 2 (5.5) 1.00

Cardiopathy, N (%) 1 (8.3) 5 (13.9) 1.00

Malignancies, N (%) 2 (16.7) 3 (8.3) 0.59

Immune system diseases, N (%) 1 (8.3) 1 (2.8) 1.00

Immune-modulating therapies, N (%)d 2 (16.7) 2 (5.5) 0.26

Renal or hepatic dysfunction, N (%) 1 (8.3) 5 (13.9) 1.00

Other neurological diseases, N (%)e 1 (8.3) 4 (11.1) 1.00

COVID-19 symptoms

Fever, N (%) 10 (83.3) 2 (5.5) <0.001

Cough, N (%) 9 (75%) 3 (8.3) <0.001

Dyspnea, N (%) 4 (33.3) 0 (0.0) 0.003

Dizziness, N (%) 2 (16.6) 1 (2.8) 0.15

Headache, N (%) 4 (33.3) 3 (8.3) 0.055

Anorexia, N (%) 5 (41.6) 1 (2.8) 0.002

Diarrhea, N (%) 6 (50) 2 (5.5) 0.002

Fatigue, N (%) 7 (58.4) 3 (8.3) <0.001

(Continues)

1288 Movement Disorders, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2020

C O V I D - 1 9 E F F E C T S O N P D S Y M P T O M S

TABLE 1. Continued

Variable Cases, N = 12 Controls, N = 36 P Value*

Skeletal muscle pain, N (%) 7 (58.4) 2 (5.5) <0.001

Nausea/vomiting, N (%) 2 (16.6) 1 (2.8) 0.15

Smell loss, N (%) 4 (33.3) 1 (2.8) 0.011

Taste loss, N (%) 2 (16.6) 1 (2.8) 0.15

Hypotension, N (%) 2 (16.6) 1 (2.8) 0.15

a

These data refer to the baseline state (January 2020) before the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy.

b

One case was on levodopa/carbidopa gel infusion; 1 control was on subthalamic nucleus stimulation.

c

Defined according to the World Health Organization criteria.14

d

Including daily intake of drugs targeting rheumatic diseases or malignancies (eg, steroids, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, etc.) prior to the baseline assessment.

e

One patient with meningioma among cases, 4 patients with chronic cerebrovascular disease among controls.

*Between-group comparisons of continuous variables were performed using the unpaired Student’s t test, whereas categorical variables were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test.

Significant values (P < 0.05) are in bold.

H1N1, haemagglutinin type 1 and neuraminidase type 1; PD, Parkinson’s disease; DA, dopamine agonists; iMAO-B, monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors; iCOMT, catechol-O-

methyltransferase inhibitors; LEDD, levodopa equivalent daily dose; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, including asthma.

patients with PD (men, 56.6%; age, 69.1 ± 10.1 years; for the greater need to increase dopaminergic therapy

PD duration, 8.2 ± 5.0 years; any comorbidity, 62.8%), dosing and higher rate of contacts with confirmed

the cases has similar sex distribution (P = 0.37), age COVID-19 among cases (Table 1). COVID-19 symp-

(P = 0.24), PD duration (P = 0.20), and comorbidities toms were mild, managed at home without symptom-

(P = 0.54). Among the 129 patients screening negative atic therapy in 3 cases (25%); 8 cases (66.7%) had

for COVID-19, a group of 36 control patients with PD moderate illness, pharmacologically managed at home

matched for sex, age, and disease duration (±1 year) by the general practitioner; only 1 patient was hospital-

was used for subsequent statistical analysis. A 1:3 ratio ized (8.3%) as a result of pneumonia. COVID symp-

was chosen to minimize the effects related to biological toms remitted in 10 of 12 (83.3%) cases and were still

variability and the potential presence of asymptomatic ongoing in 2 patients (16.7%; both remitted at subse-

COVID-19 among controls.19 Cases and matched con- quent follow-up on May 15); nobody died.

trols underwent in-depth assessment using internation- In the within-group comparisons, cases evidenced a

ally validated scales. Motor aspects of experiences of significant worsening of the CISI-PD total and motor-

daily living and the severity of treatment-related motor signs scores, MDS-UPDRS Part II score, the NMSS

complications were assessed using the Movement Dis- total score, and the urinary domain subscore (Table 2,

orders Society Unified PD Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) footnote c). Between-group case-control analysis addi-

Parts II and IV, respectively20; nonmotor symptoms tionally revealed greater motor disability (at CISI-PD),

were assessed using of the Italian version of the Non- motor fluctuations (at MDS-UPDRS Part IV), and

Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS)21; and overall changes nonmotor complaints. The involvement of cognitive

of motor and nonmotor features were additionally functions was marginal (no change at CISI-PD), and

rated using the Clinical Impression of Severity Index for autonomic cardiovascular and sexual functions remained

Parkinson’s Disease (CISI-PD).22 unaffected (Table 2).

Descriptive statistics were provided for continuous Finally, considering the greater rate of diarrhea among

(mean and standard deviation) and categorical (count COVID-19 cases (Table 1) and its detrimental effect on

and percentage) variables, which were compared the pharmacokinetics of dopaminergic medications (par-

between groups using Student’s t test and Fisher’s exact ticularly levodopa), we adjusted a selected subset of

test. Between-visit changes in study parameters (January models for this symptom and found that worsening of

to April 2020) were compared between COVID-19 cases the CISI-PD total and motor signs scores was partially

and controls using repeated-measure linear regression mediated by diarrhea (P = 0.002 for both), although

models. The role of potential confounders was addressed COVID-19 status was still a significant contributor

by Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). All (P = 0.025 and 0.026, respectively). Worsening of MDS-

statistical analyses were performed using STATA statisti- UPDRS Part II and the Part IV total scores and the

cal software release 15.1 (Stata Corporation, College NMSS total score were explained by COVID-19 alone

Station, TX) setting the level of significance at a (P = 0.008, P = 0.034, P = 0.008, respectively); interest-

2-tailed P < 0.05. ingly, an increase in daily off time was fully explained

by diarrhea (P = 0.019). We additionally explored

Results whether urinary dysfunction and fatigue were attributed

to COVID-19 or to diminished dopaminergic drive

Demographic and clinical features at baseline were (Table 2) and found that urinary problems worsening

similar between PD cases and matched controls except was the result of both motor fluctuations (P < 0.001)

Movement Disorders, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2020 1289

C I L I A E T A L

TABLE 2. Analysis of study end points (CISI-PD, MDS-UPDRS, NMSS)

Cases, N = 12 Controls, N = 36 Statistics

End of End of Between-Group Difference in P

Variable Baseline* Study* Change** Baseline* Study* Change** Change**,*** Value***

CISI-PD

Total score 6.2 (4.1) 7.4 (4.1) 1.3 (0.3–2.2)d 7.5 (4.7) 7.6 (4.8) 0.1 (0.0–0.2) 1.2 (0.6–1.7) <0.001

Motor signs 2.3 (1.4) 3.0 (1.3) 0.7 (0.2–1.2)d 2.7 (1.4) 2.7 (1.4) 0.0 (−0.0 to 0.1) 0.6 (0.3–0.9) <0.001

Disability 2.1 (1.1) 2.4 (1.4) 0.3 (−0.1 to 0.7) 2.4 (1.4) 2.4 (1.4) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 0.3 (0.1–0.5) 0.003

Motor 0.6 (1.2) 0.7 (1.4) 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.3) 1.0 (1.4) 1.0 (1.4) 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.2) 0.42

complications

Cognitive status 1.2 (1.2) 1.3 (1.2) 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.4) 1.5 (1.5) 1.5 (1.5) 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) 0.1 (−0.0 to 0.3) 0.089

MDS-UPDRS

UPDRS Part II 11.9 (7.6) 13.7 (9.4) 1.8 (0.4–3.1)c 12.0 (8.3) 12.2 (8.3) 0.2 (0.0–0.4)c 1.6 (0.8–2.3) <0.001

UPDRS Part IV 3.0 (6.2) 4.2 (8.1) 1.2 (−0.2 to 2.5) 4.8 (6.6) 4.8 (6.6) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 1.2 (0.5–2.9) 0.002

UPDRS Part IV, 1.1 (2.0) 1.5 (2.8) 0.4 (−0.2 to 1.0) 1.7 (2.5) 1.7 (2.5) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 0.4 (0.1–0.7) 0.014

offa

UPDRS Part 0.3 (1.2) 0.5 (1.7) 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.5) 0.6 (1.2) 0.6 (1.2) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 0.2 (−0.0 to 0.4) 0.083

IV–DYSKa

NMSS

Total score 39.3 (28.1) 49.7 (43.1) 10.4 (0.2–20.6)c 41.9 (40.8) 41.8 (41.1) −0.1 (−0.7 to 0.5) 10.5 (5.2–15.9) <0.001

Cardiovascular 1.5 (1.3) 1.8 (3.3) 0.3 (−1.1 to 1.6) 1.3 (2.3) 0.9 (1.9) −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2)c 0.6 (−0.2 to 1.4) 0.13

Sleep/fatigue 8.3 (6.4) 10.5 (7.1) 2.2 (−0.2 to 4.6) 10.0 (9.7) 9.8 (9.7) −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.1) 2.3 (1.0–3.6) 0.001

Mood/apathy 8.6 (14.3) 11.8 (17.9) 3.2 (−1.2 to 7.5) 7.6 (11.0) 7.6 (11.3) 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.4) 3.1 (0.8–5.5) 0.010

Perceptual 0.9 (1.6) 0.9 (1.6) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 0.7 (1.6) 0.7 (1.6) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 1.00

problems

Attention/ 3.2 (4.1) 4.7 (7.8) 1.5 (−1.1 to 4.1) 4.9 (7.1) 4.9 (7.1) 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) 1.4 (0.1–2.8) 0.038

memory

Gastrointestinalb 3.3 (5.1) 3.2 (5.2) −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.5) 3.0 (3.8) 3.2 (3.9) 0.2 (−0.0 to 0.4) −0.4 (−0.9 to 0.2) 0.17

Urinary 8.6 (7.5) 10.8 (9.3) 2.2 (0.1–4.4)c 8.3 (9.0) 8.3 (9.0) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 2.3 (1.1–3.4) <0.001

Sexual function 1.3 (2.0) 1.3 (2.0) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 2.1 (4.5) 2.1 (4.5) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 0.0 (0.0–0.0) 1.00

Miscellaneous 3.5 (3.3) 4.8 (3.7) 1.3 (−0.5 to 3.0) 4.2 (5.9) 4.3 (5.9) 0.1 (−0.0 to 0.2) 1.2 (0.2–2.1) 0.014

*Data are provided as mean (standard deviation).

**Data are provided as mean (95% confidence interval).

***According to repeated-measures linear regression model.

a

Off-related subscore was calculated as the sum of items 4.3, 4.4, and 4.5. Dyskinesia subscore was calculated as the sum of items 4.1 and 4.2.

b

Note that the gastrointestinal domain of the NMSS does not include an assessment of diarrhea.

c

Significantly different compared with baseline (test for within-group comparison).

CISI-PD, Clinical Impression of Severity Index for Parkinson’s Disease; MDS-UPDRS, Movement Disorders Society Unified PD Rating Scale; NMSS, Non-Motor

Symptoms Scale; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; DYSK, dyskinesia.

and COVID-19 (P = 0.005), whereas fatigue was attrib- that mild to moderate COVID-19 may be contracted

uted to COVID-19 alone (P < 0.001). independently of age and PD duration and that patients

with PD with mid-stage PD do not seem to have an

overall worse outcome than the non-PD population.15

Discussion Concerning the primary objective of the study, we

To our knowledge, this is the first community-based found a worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms

case-control study describing the effects of symptomatic of PD during the study period in the COVID-19 group

COVID-19 on PD motor and nonmotor symptoms. when compared with the matched controls.

First, patients with PD who developed symptomatic

COVID-19 were neither older age nor had longer dis- Motor Symptoms

ease duration than those who screened negative, but COVID-19 induced a significant worsening of motor

had nonsignificant 3.5-year younger age and 2.0-year performance, motor-related disability, and experiences of

shorter disease durations. The lack of case fatalities is daily living. Worsening of levodopa-responsive motor

consistent with the Italian case fatality rate of 3.5% at symptoms and increased daily off time, caused either by

60 to 69 years of age.15 Similarly, only 1 patient the effects of acute systemic inflammatory response6-9 or

(8.3%) needed to be admitted to the hospital for severe by changes in pharmacokinetics, was so pronounced in

COVID-19 illness, which is consistent with the fre- one third of cases to prompt neurologists to increase

quency of hospitalization previously reported in the dopaminergic therapy. We explored the relative contri-

general population of the Lombardy region.23 We bution of suboptimal absorption of oral therapy by

expand previous report in advanced PD12 and show adjusting motor end points for diarrhea, which was

1290 Movement Disorders, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2020

C O V I D - 1 9 E F F E C T S O N P D S Y M P T O M S

present in 50% of cases. According to multivariate anal- Conclusions

ysis, concomitant diarrhea explained the increase in

motor fluctuations, but could not entirely explain the Patients with PD may experience substantial worsen-

worsening of motor disability and motor aspects of expe- ing of motor and nonmotor symptoms during mild to

riences of daily living. moderate COVID-19 illness, independent of age and

disease duration. Clinicians should take pharmacoki-

netic changes into consideration before adjusting ther-

Nonmotor Symptoms apy regimens (eg, management of dehydration

secondary to fever, diarrhea, anorexia with reduced

COVID-19 significant aggravated a number of non-

water intake). Although we speculate that subacute

motor symptoms. Increased fatigue in our cohort was

clinical changes in PD associated with nonsevere

fully explained by COVID-19, confirming that it is a

COVID-19 illness are likely caused by systemic inflam-

common COVID-19 symptom,24 as described in PD

matory response8,9 rather than a direct invasion of the

following systemic inflammation.25 Urinary urge/incon-

central nervous system,27,28 further studies in larger PD

tinence and nicturia were explained by the infection as

populations are warranted to clarify the cause–effect

well as increased motor fluctuations, which were partly

relationship among clinical changes and the severity of

a result of pharmacokinetic issues. COVID-19 was nei-

COVID-19 illness, cytokine levels, and virus detection

ther a major cause of cognitive dysfunction nor auto-

in the cerebrospinal fluid.

nomic failure in our cohort of mid-stage PD. Although

there was an effect of COVID-19 on attention, it was

not severe enough to be detected by CISI-PD. We did Acknowledgments: We are thankful to Francesca De Giorgi for pro-

viding the dataset of patients with parkinsonism resident visited at the

not find changes in cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or Besta Institute.

sexual function domains in the NMSS or differences in

hypotension between the groups.

References

1. Coronavirus COVID-19 global cases by the Center for Systems Sci-

Strengths and Limitations ence and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins. https://gisanddata.

maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd402

The main limitation of this study is the small cohort 99423467b48e9ecf6. Accessed May 7, 2020.

of COVID-19 patients, albeit statistical analysis could 2. Stoessl AJ, Bhatia KP, Merello M. Editorial: movement disorders in

detect several significant changes. There are a number the world of COVID-19. Mov Disord 2020;35(5):709–710.

of strengths worth mentioning. First, our case-control 3. Papa SM, Brundin P, Fung VSC, et al. Impact of the COVID-19

study protocol excluded the detrimental effects that pandemic on Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Mov Dis-

ord 2020;35(5):711–715.

quarantine and lockdown restrictions might have

4. Helmich RC, Bloem BR. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on

played on a number of confounders that influence PD Parkinson’s disease: hidden sorrows and emerging opportunities.

motor and nonmotor symptoms, such as reduced physi- J Parkinsons Dis 2020;10(2):351–354.

cal activity, enhanced stress, confusion, anxiety, and 5. Labandeira-Garcia JL, Rodriguez-Pallares J, Dominguez-Meijide A,

Valenzuela R, Villar-Cheda B, Rodríguez-Perez AI. Dopamine-

sleep disturbances.26 Second, a community-based sur- angiotensin interactions in the basal ganglia and their relevance for

vey minimized selection bias related to the inclusion of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2013;28(10):1337–1342.

hospitalized patients with severe illness or institutional- 6. Lindqvist D, Kaufman E, Brundin L, Hall S, Surova Y, Hansson O.

ized patients with advanced PD and comorbidities who Non-motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease - correla-

tions with inflammatory cytokines in serum. PLoS ONE 2012;7(10):

are more susceptible to a worst outcomes of neurologi- e47387.

cal manifestations.27,28 Our cohort with mild to moder- 7. Green HF, Khosousi S, Svenningsson P. Plasma IL-6 and IL-17A

ate illness is likely representative of the majority of correlate with severity of motor and non-motor symptoms in

patients with PD affected by COVID-19, considering Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2019;9(4):705–709.

that only a minority of cases required hospitaliza- 8. Brugger F, Erro R, Balint B, Kägi G, Barone P, Bhatia KP. Why is

there motor deterioration in Parkinson’s disease during systemic

tion.29-31 Third, we excluded secondary and atypical infections-a hypothetical view. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2015;1:15014.

parkinsonisms (including dementia with Lewy bodies), 9. Umemura A, Oeda T, Tomita S, Hayashi R, Kohsaka M, Park K,

minimizing the risk of overestimating either fluctuating Sugiyama H, Sawada H. Delirium and high fever are associated with

subacute motor deterioration in Parkinson disease: a nested case-

or drug-induced worsening of cognitive dysfunction, control study. PLoS ONE 2014;9(6):e94944.

visual hallucinations, and autonomic failure. Finally, 10. Vijayan S, Singh B, Ghosh S, Stell R, Mastaglia FL. Brainstem venti-

our comprehensive assessment performed by experi- lator dysfunction: a plausible mechanism for dyspnea in Parkinson’s

enced neurologists in a single tertiary referral clinic disease? Mov Disord 2020;35(3):379–388.

ensured a homogeneous and standardized approach. 11. Titova N, Qamar MA, Chaudhuri KR. The nonmotor features of

Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 2017;132:33–54.

Larger multicenter studies would have requested longer

12. Antonini A, Leta V, Teo J, Chaudhuri KR. Outcome of Parkinson’s

time for data collection, increasing patient/caregiver disease patients affected by COVID-19. Mov Disord 2020;35(6):

recall bias. 905–908.

Movement Disorders, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2020 1291

C I L I A E T A L

13. Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria 22. Martínez-Martín P, Forjaz MJ, Cubo E, Frades B, de Pedro

for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2015;30:1591–1600. Cuesta J, ELEP Project Members. Global versus factor-related

impression of severity in Parkinson’s disease: a new clinimetric index

14. World Health Organization. Global surveillance for COVID-19 cau- (CISI-PD). Mov Disord 2006;21(2):208–214.

sed by human infection with COVID-19 virus: interim guidance,

20 March 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331506. 23. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics

Accessed May 8, 2020. and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted

to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):

15. Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteris- 1574–1581.

tics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA Neu-

rology 2020;323(18):1775–1776. 24. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected

with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395

16. Dipartimento della Protezione Civile. COVID-19 Italia— (10223):497–506.

Monitoraggio della situazione. http://opendatadpc.maps.arcgis.com/

25. Felger JC, Miller AH. Cytokine effects on the basal ganglia and

apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/b0c68bce2cce478eaac82fe38d4138

dopamine function: the subcortical source of inflammatory malaise.

b1. Accessed May 12, 2020.

Front Neuroendocrinol 2012;33(3):315–327.

17. Gabbrielli F, Bertinato L, De Filippis G, Bonomini M, Cipolla M. 26. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact

Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Interim provisions on telemedicine of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence.

healthcare services during COVID-19 health emergency. Version of Lancet 2020;395(10227):912–920.

April 13, 2020. Rapporti ISS COVID-19 n. 12/2020. https://www.

iss.it/documents/20126/0/Rapporto+ISS+COVID-19+n.+12_2020 27. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospi-

+telemedicina.pdf/387420ca-0b5d-ab65-b60d-9fa426d2b2c7?t= talized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China

1587114370414 [published online ahead of print April 10, 2020]. JAMA Neurol.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127

18. Bloem BR, Dorsey ER, Okun MS. The coronavirus disease 2019 cri-

28. Asadi-Pooya AA, Simani L. Central nervous system manifestations

sis as catalyst for telemedicine for chronic neurological disorders

of COVID-19: a systematic review. J Neurol Sci 2020;413:116832.

[published online ahead of print April 24, 2020]. JAMA Neurol.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1452 29. Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of

COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in

19. Nishiura H, Kobayashi T, Miyama T, et al. Estimation of the Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study [published online

asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19). Int ahead of print April 27, 2020]. Lancet Infect Dis. https://doi.

J Infect Dis. 2020;94:154–155. org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5

20. Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman S, et al. Movement Disorder Society 30. Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Place S, et al. Clinical and epide-

UPDRS Revision Task Force. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored miological characteristics of 1,420 European patients with mild-to-

revision of the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (MDS- moderate coronavirus disease 2019 [published online ahead of print

UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Dis- April 30, 2020]. J Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13089

ord 2008;23:2129–2170.

31. Kim GU, Kim MJ, Ra SH, et al. Clinical characteristics of asymp-

21. Cova I, Di Battista ME, Vanacore N, et al. Validation of the Italian tomatic and symptomatic patients with mild COVID-19 [published

version of the non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson’s disease. online ahead of print April 30, 2020]. Clin Microbiol Infect. https://

Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;34:38–42. doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.040

1292 Movement Disorders, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2020

You might also like

- MCPS Form For Annual Sports Physical Exam - (PPE) 2010 Edition Prepared by Am Academy of Ped, Am. Academy of Family Phys Et Al.Document5 pagesMCPS Form For Annual Sports Physical Exam - (PPE) 2010 Edition Prepared by Am Academy of Ped, Am. Academy of Family Phys Et Al.Concussion_MCPS_MdNo ratings yet

- Psychiatrics McqsDocument20 pagesPsychiatrics McqsHirwaNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Review Cardiovascular QuizDocument17 pagesNCLEX Review Cardiovascular QuizApple Mesina100% (2)

- Emergency Nursing: By: Keverne Jhay P. ColasDocument61 pagesEmergency Nursing: By: Keverne Jhay P. ColasGaras AnnaBerniceNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Mortality Review in Malaysia & Updates on Clinical Management of COVID-19From EverandCOVID-19 Mortality Review in Malaysia & Updates on Clinical Management of COVID-19No ratings yet

- Effects of COVID-19 On Parkinson Disease Clinical Features - A CMDocument12 pagesEffects of COVID-19 On Parkinson Disease Clinical Features - A CMAntonyNo ratings yet

- Retinal Findings in Patients COVID19Document1 pageRetinal Findings in Patients COVID19María de Lourdes EspejelNo ratings yet

- Movement Disorders in COVID 19 Times Impact On.9Document8 pagesMovement Disorders in COVID 19 Times Impact On.9Putu AfruriNo ratings yet

- Impact of Diabetes On COVID-19-Releated in Hospital MortalityDocument8 pagesImpact of Diabetes On COVID-19-Releated in Hospital MortalityDaniela VelascoNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Medicine and GerontologyDocument7 pagesGeriatric Medicine and GerontologyNoor FadlanNo ratings yet

- Scab 066Document12 pagesScab 066Djfiory YonutzNo ratings yet

- Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, ChinaDocument7 pagesDysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, Chinacika daraNo ratings yet

- Biomarkers of Ageing and Frailty May Predict COVID-19 SeverityDocument13 pagesBiomarkers of Ageing and Frailty May Predict COVID-19 SeverityPPDS Rehab Medik UnhasNo ratings yet

- Bianchetti 2020Document6 pagesBianchetti 2020GembongSatriaMahardhikaNo ratings yet

- JAPI0200 p19-24 CompressedDocument6 pagesJAPI0200 p19-24 Compressedsachin kulkarniNo ratings yet

- FM, Nueva Faceta Post CovidDocument10 pagesFM, Nueva Faceta Post Covidtavo570No ratings yet

- 2020 - Ajslp 20 00147Document12 pages2020 - Ajslp 20 00147Luis.fernando. GarciaNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Characterisation of post-COVID-19 ManifestationsDocument5 pagesAssessment and Characterisation of post-COVID-19 ManifestationsAlexandra IonițăNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Efficacy of Ivermectin As An Adjuvant in The Treatment of Patients With COVID-19Document5 pagesTherapeutic Efficacy of Ivermectin As An Adjuvant in The Treatment of Patients With COVID-19International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Funciones y Actividades Plaquetarias Como Posibles Parámetros Hematológicos Relacionados Con La Enfermedad Por CoronavirusDocument7 pagesFunciones y Actividades Plaquetarias Como Posibles Parámetros Hematológicos Relacionados Con La Enfermedad Por CoronavirusEdinson Cortez VasquezNo ratings yet

- Impact of COVID-19 On Primary Care Visits: Lesson Learnt From The Early Pandemic PeriodDocument10 pagesImpact of COVID-19 On Primary Care Visits: Lesson Learnt From The Early Pandemic PeriodRino RinzNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Interleukin-6 Level Changes As A Prognostic Indicator in Patients With COVID-19Document11 pagesDynamic Interleukin-6 Level Changes As A Prognostic Indicator in Patients With COVID-19dariusNo ratings yet

- Conjunctivitis and COVID 19: A Meta Analysis: LettertotheeditorDocument2 pagesConjunctivitis and COVID 19: A Meta Analysis: LettertotheeditorAngel LimNo ratings yet

- Long COVID Guidelines Need To Reflect Lived Experience: CommentDocument3 pagesLong COVID Guidelines Need To Reflect Lived Experience: CommentAlexandra PimentaNo ratings yet

- Kidney Disease Is Associated With In-Hospital Death of Patients With COVID-19Document10 pagesKidney Disease Is Associated With In-Hospital Death of Patients With COVID-19Kevin OwenNo ratings yet

- Fisiopatologia, Presentación y Abordaje Del Delirium en Covid 19Document16 pagesFisiopatologia, Presentación y Abordaje Del Delirium en Covid 19paola coralNo ratings yet

- Contactless In-Home Monitoring of The Long-Term Respiratory and Behavioral Phenotypes in Older Adults With COVID-19Document8 pagesContactless In-Home Monitoring of The Long-Term Respiratory and Behavioral Phenotypes in Older Adults With COVID-19Sarah Nauman GhaziNo ratings yet

- ECI 9999 E13314Document6 pagesECI 9999 E13314WilsonR.CorzoNiñoNo ratings yet

- Modeling The Onset Syntoms of CovidDocument14 pagesModeling The Onset Syntoms of CovidMiguel R MoNo ratings yet

- Montelukast in COVID-4Document6 pagesMontelukast in COVID-4Golam JILANI Mahbubay AlamNo ratings yet

- Presidential Memorandum On Long-Term Effects of COVID-19Document2 pagesPresidential Memorandum On Long-Term Effects of COVID-19rodriguezdiazNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Infection and Seropositivity in Multiple Sclerosis Patients in Guilan in 2021Document11 pagesCOVID-19 Infection and Seropositivity in Multiple Sclerosis Patients in Guilan in 2021samaneh shirkouhiNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease PatientsDocument11 pagesCOVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Patientsblume diaNo ratings yet

- Covid-19-Linked Loss of Smell and Taste - Case Study and DiscussionDocument5 pagesCovid-19-Linked Loss of Smell and Taste - Case Study and DiscussionGalletNo ratings yet

- Jennings Et Al (Dic-2021)Document15 pagesJennings Et Al (Dic-2021)Sergio GarcíaNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and Smoking: What Evidence Needs Our Attention?Document9 pagesCOVID-19 and Smoking: What Evidence Needs Our Attention?elguyoNo ratings yet

- Fimmu 13 857573Document11 pagesFimmu 13 857573Bruno QueirozNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and Guillain-Barré Syndrome, A Single-Center Prospective Case Series With A 1-Year Follow-UpDocument8 pagesCOVID-19 and Guillain-Barré Syndrome, A Single-Center Prospective Case Series With A 1-Year Follow-UpLuciano RuizNo ratings yet

- Long Term Neuropsychiatric Consequences in COVID-19 Survivors Cognitive Impairment and Inflammatory Underpinnings Fifteen Months After DischargeDocument8 pagesLong Term Neuropsychiatric Consequences in COVID-19 Survivors Cognitive Impairment and Inflammatory Underpinnings Fifteen Months After DischargeLaura PulidoNo ratings yet

- 2299-Article Text-26374-3-10-20220428Document6 pages2299-Article Text-26374-3-10-20220428anne claire feudoNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Practice On Covid-19 Among General PublicDocument4 pagesKnowledge and Practice On Covid-19 Among General PublicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Quadmester-Wise Comparison of Disease Transmission Dynamics of COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers in Kannur District, KeralaDocument7 pagesQuadmester-Wise Comparison of Disease Transmission Dynamics of COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers in Kannur District, KeraladrdeepudentNo ratings yet

- Association of COVID 19 With Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisDocument8 pagesAssociation of COVID 19 With Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisAgatha GeraldyneNo ratings yet

- Association of Procalcitonin Levels With The Progression and Prognosis of Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19Document9 pagesAssociation of Procalcitonin Levels With The Progression and Prognosis of Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19Dian Putri NingsihNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) : A Perspective From ChinaDocument11 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) : A Perspective From Chinasri karuniaNo ratings yet

- E696 FullDocument10 pagesE696 FullotakualafugaNo ratings yet

- Does Amantadine Have A Protective Effect Against CDocument3 pagesDoes Amantadine Have A Protective Effect Against CAleksandra MarciniakNo ratings yet

- Diabetes and COVID-19 Testing, Positivity, and MortalityDocument6 pagesDiabetes and COVID-19 Testing, Positivity, and MortalityDiana MontoyaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectAntonio Barrios PerezNo ratings yet

- Review: Li Jiang, Kun Tang, Mike Levin, Omar Irfan, Shaun K Morris, Karen Wilson, Jonathan D Klein, Zulfiqar A BhuttaDocument13 pagesReview: Li Jiang, Kun Tang, Mike Levin, Omar Irfan, Shaun K Morris, Karen Wilson, Jonathan D Klein, Zulfiqar A BhuttaMaria Carolina FallaNo ratings yet

- IJGMP - Format-Association Thyroid Function To Prognosis of COVID 19Document8 pagesIJGMP - Format-Association Thyroid Function To Prognosis of COVID 19iaset123No ratings yet

- Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Inelderly With Dementia DuringCOVID-19 PandemicDocument9 pagesNeuropsychiatric Symptoms Inelderly With Dementia DuringCOVID-19 Pandemicmadalena limaNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin and Secondary Bacterial InfectionsDocument6 pagesProcalcitonin and Secondary Bacterial Infectionsadrifen adriNo ratings yet

- Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsDocument5 pagesDiabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsRea AuliaNo ratings yet

- Bencivenga 2020Document4 pagesBencivenga 2020GembongSatriaMahardhikaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022510X22003495 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0022510X22003495 MainoscarNo ratings yet

- Predictors of COVID-19 Severity: A Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesPredictors of COVID-19 Severity: A Literature ReviewRafiqua Sifat JahanNo ratings yet

- 2020 - Ajslp 20 00147Document12 pages2020 - Ajslp 20 00147Maha KhanNo ratings yet

- Pengumuman THT-KL 2022Document10 pagesPengumuman THT-KL 2022Citra LyadhaNo ratings yet

- Covid 19 Review PaperDocument25 pagesCovid 19 Review PaperLeena MuniandyNo ratings yet

- The Study of Clinical Profile of Acute Kidney Injury in COVID-19 PatientsDocument6 pagesThe Study of Clinical Profile of Acute Kidney Injury in COVID-19 PatientsbijgimNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1473309921007039 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1473309921007039 MainCamilo Andrés CastroNo ratings yet

- METHAMEDICINDocument21 pagesMETHAMEDICINRobert ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Current Prevalence, Characteristics, and Comorbidities of Patients With COVID-19 in IndonesiaDocument8 pagesCurrent Prevalence, Characteristics, and Comorbidities of Patients With COVID-19 in IndonesiaAkreditasi InternaNo ratings yet

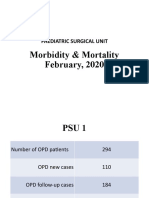

- Morbidity & Mortality (February, 2020)Document14 pagesMorbidity & Mortality (February, 2020)Wai GyiNo ratings yet

- Jake Yvan Dizon Case Study, Chapter 49, Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic DisordersDocument8 pagesJake Yvan Dizon Case Study, Chapter 49, Assessment and Management of Patients With Hepatic DisordersJake Yvan DizonNo ratings yet

- Viral Skin InfectionsDocument28 pagesViral Skin Infectionstolesadereje73No ratings yet

- Case Files® EnterococcusDocument4 pagesCase Files® EnterococcusAHMAD ADE SAPUTRANo ratings yet

- Bugnao v. Ubag, GR No. 4445, 18 September 1909Document2 pagesBugnao v. Ubag, GR No. 4445, 18 September 1909Judel MatiasNo ratings yet

- Diseases: July 2021Document246 pagesDiseases: July 2021Mkaruka BrellaNo ratings yet

- Keamanan Pangan Hasil PerikananDocument42 pagesKeamanan Pangan Hasil PerikananBhatara Ayi MeataNo ratings yet

- I. Nursing Care Plan Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention EvaluationDocument3 pagesI. Nursing Care Plan Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention EvaluationCherubim Lei DC FloresNo ratings yet

- Legalizing Marijuana FinalDocument18 pagesLegalizing Marijuana FinalTeresa EvripidouNo ratings yet

- Ann-Charlotte Granholm, David Bachman, Jacobo Mintzer, Kumar SambamurtiDocument2 pagesAnn-Charlotte Granholm, David Bachman, Jacobo Mintzer, Kumar SambamurtiAlexandru TanaseNo ratings yet

- Edu 259 p1 Prof Ed Edu 259 p1 Prof EdDocument92 pagesEdu 259 p1 Prof Ed Edu 259 p1 Prof EdkriztheiaaveriennenievesNo ratings yet

- Medical Emergencies in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery KHADIJA-5Document81 pagesMedical Emergencies in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery KHADIJA-5Khadija VasiNo ratings yet

- Bayes' Theorem in Paleopathological Diagnosis PDFDocument9 pagesBayes' Theorem in Paleopathological Diagnosis PDFjessyramirez07No ratings yet

- Lab Final Exam ReviewDocument59 pagesLab Final Exam ReviewManju ShreeNo ratings yet

- Health Facts 2020Document19 pagesHealth Facts 2020haikal11No ratings yet

- J. Dizon vs. Naess Shipping Phils., Inc. G.R. No. 201834 DawisanDocument2 pagesJ. Dizon vs. Naess Shipping Phils., Inc. G.R. No. 201834 DawisanMae Clare BendoNo ratings yet

- Notes On UtiDocument15 pagesNotes On UtiSaleh Mohammad ShoaibNo ratings yet

- Volume 23 Chapter 4 - Supard Race's VillageDocument21 pagesVolume 23 Chapter 4 - Supard Race's VillageCastro CarlosNo ratings yet

- Current Application of Cannabidiol (CBD) in The Management and Treatment of Neurological DisordersDocument14 pagesCurrent Application of Cannabidiol (CBD) in The Management and Treatment of Neurological Disorderssara laadamiNo ratings yet

- Soy2020 Article CytokineStormInCOVID-19PathogeDocument10 pagesSoy2020 Article CytokineStormInCOVID-19PathogeGumoNo ratings yet

- UlcerDocument3 pagesUlcerMd Ahsanuzzaman PinkuNo ratings yet

- Final Project IdeaDocument2 pagesFinal Project IdeaAniqa waheedNo ratings yet

- EDITED 02chapter 1 Aratiles OintmentDocument9 pagesEDITED 02chapter 1 Aratiles OintmentMikhaela Andree MarianoNo ratings yet

- 13463-Article Text-25834-1-10-20210103Document3 pages13463-Article Text-25834-1-10-20210103Melly SyafridaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of MicrobiologyDocument48 pagesEvolution of MicrobiologyArielleNo ratings yet

- Radiological Anatomy of Stomach and Duodenum With Clinical SignificanceDocument9 pagesRadiological Anatomy of Stomach and Duodenum With Clinical SignificancepouchkineNo ratings yet