Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Society For Unaided Private Schools V India: Case-Law Summary

Uploaded by

Trinity NagpalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Society For Unaided Private Schools V India: Case-Law Summary

Uploaded by

Trinity NagpalCopyright:

Available Formats

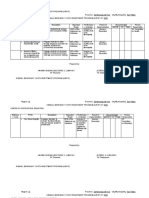

Case-law summary

Decisions by judicial and quasi-judicial

bodies on the right to education

Society for Unaided Private Schools v India

(Supreme Court of India; 2012)

Case at a glance

Full citation

Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan v Union of India & Another (2012) 6

SCC; Writ Petition (C) No. 95 of 2010

Forum

Supreme Court of India

Date of decision

12 April 2012

Summary of decision

In this decision, the Supreme Court of India upheld the constitutionality of section 12 of

the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (RTE Act), which requires all

schools, both state-funded and private, to accept 25% intake of children from

disadvantaged groups. However, the Court held that the RTE Act could not require

private, minority schools to satisfy a 25% quota, as this would constitute a violation of

the right of minority groups to establish private schools under the Indian Constitution.

Significance to the right to education

This case affirms that the authority of the State to fulfil its obligations under the right to

education can be extended to private, non-State actors. Because the State has the

authority to determine the manner in which it discharge this obligation, it can elect to

impose statutory obligations on private schools so long as the requirements are in the

public interest.

Issues and keywords

Regulation of private schools; Public interest; Privatisation; Duties of non-State actors;

Minorities; Equality and non-discrimination

This case-law summary is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice.

© Right to Education Project; July 2015 www.right-to-education.org 1

Context Article 21-A of the

In 2009, the Indian Parliament enacted the Right of Children to Free Indian Constitution

and Compulsory Education Act (RTE Act), pursuant to Article 21-A of

the Indian Constitution which requires the government to provide

“The State shall provide free

free and compulsory education to all children aged 6-14.

and compulsory education to

Section 12 of the RTE Act requires that all aided (state-run) and all children of the age of six

unaided (private) schools reserve 25% of their admissions for students to fourteen years in such

from economically weaker and socially disadvantaged backgrounds. manner as the State may, by

law, determine. “

Facts

The Society for Unaided Private Schools – an association of privately run schools – challenged the

constitutionality of section 12 of the RTE Act on the basis that imposing regulatory requirements on private

schools violated the right to practice any profession or occupation free from government interference under

Article 19 of the Constitution, and the right of minority groups to establish and administer schools under

Article 30 of the Constitution.

Issue

The main issue before the Court was the constitutionality of the RTE Act, with two primary questions:

1. Whether requiring private schools to satisfy mandatory quotas violated Article 19 of the Constitution,

which guarantees the right to practise any profession or occupation.

2. Whether requiring minority private schools to satisfy quotas violates Article 30 of the Constitution,

which protects the right of minority groups to establish and administer private schools.

Decision

In its majority decision, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the mandatory quota as it applies to private

and state-run schools. Therefore, the Court decided that the government may constitutionally require private

schools to reserve 25% of its admission places for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The Court reasoned that the RTE Act is “child centric and not institution centric”, meaning that the provision

of education to all children is a priority, irrespective of the fact that it might burden private schools. The court

reiterated the importance of Article 21-A, and

found that the burden on private schools to satisfy

“… the obligation is on the State to provide

the quota was irrelevant in light of the importance

free and compulsory education to all children of the right to education.

of a specified age. However, ... the manner in

which the said obligation will be discharged The Court reiterated that the State’s primary

by the State has been left to the State to obligation is to provide for free and compulsory

determine by law. Thus, the State may decide education to all children, particularly those who

cannot afford primary education. Although there is

to provide free and compulsory education to

a right to establish private schools under Article 19,

all children of the specified age through its which guarantees the right to practise any trade or

own schools or through government aided profession, the Court held that this right only exists

schools or through unaided private schools.” where the school remains charitable and not for-

profit.

© Right to Education Project; July 2015 www.right-to-education.org 2

Because establishing a private school under

Article 19 supplements the primary obligation

Relevant Legal Provisions

of the State, the Court held that the State can

regulate private schools by imposing

National

reasonable restrictions in the public interest Article 21A, Constitution of India

under Article 19(6). The Court further Section 12, Right of Children to Free and

concluded that the 25% quota imposed on Compulsory Education Act 2009

private schools is in the public interest and is a

reasonable restriction for the purposes of International

Article 19(6). Therefore, the 2009 Act was Article 26, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

deemed to be constitutional and enforceable Article 28, Convention on the Rights of the Child

against private schools. Articles 13 and 14, International Covenant on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

However, the Court made a distinction

between private schools and private minority

schools, established under Article 30 of the Constitution, and held that the government cannot require

private minority schools to satisfy a 25% quota. To do so would constitute a violation of the right of minority

groups to establish private schools under Article 30. The court reasoned that Article 29(1) of the Constitution

protects the right of minorities to conserve their language, script or culture, and Article 30(1) protects their

right to establish and administer schools of their choice. Therefore, imposing a quota on such schools would

result in changing their character and would therefore violate these rights.

Commentary

This case affirms that the authority of the State to fulfil its obligations under the right to education can be

extended to private, non-State actors. According to the majority opinion, the State has an obligation to

provide free and compulsory primary education, and to ensure educational equality. Because the State has

the authority to determine the manner in which it discharge this obligation, it can elect to impose statutory

obligations on private schools so long as the requirements are in the public interest.

The broad nature of the State’s authority in this regard is demonstrated in the dissenting opinion of Judge

Radhakrishnan, which found that the RTE Act should not apply to unaided private schools. The State has

primary obligation to protect and fulfil the right to education and, according to the dissenting opinion, non-

State actors merely have a negative duty not to violate the right to education.

Related Cases

Miss Mohini Jain v State of Karnataka & Others [1992] AIR 1858

In this decision, the India Supreme Court the Court held charging of a capitation fee by the private

educational institutions violated the right to education, as implied from the right to life and human dignity,

and the right to equal protection of the laws. The Court also held that private institutions, acting as agents of

the State, have a duty to ensure equal access to, and non-discrimination the delivery of, higher education.

Environmental & Consumer Protection Foundation v Delhi Administration & Others [2012]

INSC 584

In this case, the India Supreme Court held that, under the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory

Education Act of 2009 and the Indian , central, state and local governments have an obligation to ensure that

all schools, both public and private, have adequate infrastructure.

© Right to Education Project; July 2015 www.right-to-education.org 3

Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust & Others v Additional Resources

Union of India & Others [Writ Petition No. 416 of

2012] Prashant Narange with inputs from

In this case, the India Supreme Court upheld the Minansa Ambastha. 25 per cent

constitutionality of Articles 15(5) and 21-A of the

Reservation in Private Unaided

Constitution of India, so far as they require unaided private

schools to provide compulsory education for children aged Schools: Social Justice or

6-14. However, the Court further held that private schools, Expropriation?

particularly private minority schools, could not be

compelled to provide free, compulsory education to Khagesh Gautam, Comparative

children belonging to disadvantaged groups, as this would Constitutional Law and Administrative

constitute a violation of the right of minority groups to

Law Quarterly (2014). Fundamental

establish private schools under Article 30 of the

Constitution Right to Free Primary Education in

India: A Critical Examination of

Governing Body of the Juma Musjid Primary Society for Unaided Private Schools of

School & Others v Ahmed Asruff Essay N.O. & Rajasthan v. Union of India.

Others (CCT 29/10) [2011] ZACC 13; 2011 (8) BCLR

761 (CC) The Hindu (9 May 2014). Right to

In this case, the South African Constitutional Court held Education: neither free nor

that where a public school is located on private land, the compulsory.

private landowner has a negative constitutional obligation

not to impair the right to basic education under the South

African Constitution.

About the Right to Education Project

The Right to Education Project (RTE) works collaboratively with a wide range of education actors and

partners with civil society at the national, regional and international level. Our primary activities include

conducting research, sharing information, developing policy and monitoring tools, promoting online

discussion, and building capacities on the right to education.

For more information and case-law summaries

visit www.right-to-education.org

© Right to Education Project; July 2015 www.right-to-education.org 4

You might also like

- Case Analysis - RashmiDocument6 pagesCase Analysis - Rashmirashmi gargNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis AssignmentDocument13 pagesCase Analysis AssignmentTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Summary of Society For Unaided Private Scholls of Rajasthan VS Uoi (2012) SCDocument3 pagesSummary of Society For Unaided Private Scholls of Rajasthan VS Uoi (2012) SCRadheyNo ratings yet

- India Supreme Court, Jain V Karnataka, 1992Document4 pagesIndia Supreme Court, Jain V Karnataka, 1992VivekKumarNo ratings yet

- Introduction - : Organisations Around The World Striving For Promotion of Right To Education AreDocument7 pagesIntroduction - : Organisations Around The World Striving For Promotion of Right To Education ArePriyanshu RanjanNo ratings yet

- Human Rights AssignmentDocument5 pagesHuman Rights AssignmentmanikaNo ratings yet

- Education in Mother Tongue Balancing Fundamental Rights and Reasonable RestrictionsDocument23 pagesEducation in Mother Tongue Balancing Fundamental Rights and Reasonable Restrictionssiri.srini25No ratings yet

- Salient Features of Right to Education Act 2009Document7 pagesSalient Features of Right to Education Act 2009Sanya RastogiNo ratings yet

- Case CommentDocument12 pagesCase CommentSaharsh ChitranshNo ratings yet

- Vol. LI Education Law: Supreme Court and High Courts on Right to EducationDocument46 pagesVol. LI Education Law: Supreme Court and High Courts on Right to EducationishikaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2b Article 21A Constitutional Law IIDocument6 pagesUnit 2b Article 21A Constitutional Law IIArjun SanthoshNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of The Right of Children To Free andDocument8 pagesA Critical Analysis of The Right of Children To Free andrajendra kumarNo ratings yet

- Right to Education Act ExplainedDocument14 pagesRight to Education Act Explainedayush singhNo ratings yet

- Strategy for Girl Child Education in Andhra PradeshDocument107 pagesStrategy for Girl Child Education in Andhra PradeshAlfiyani WulandariNo ratings yet

- Right to Education in India: Key Constitutional Provisions and Supreme Court JudgmentsDocument7 pagesRight to Education in India: Key Constitutional Provisions and Supreme Court JudgmentsB. Vijaya BhanuNo ratings yet

- Elementary DR IndianDocument50 pagesElementary DR IndianShobha J PrabhuNo ratings yet

- CoTesCUP v Sec. of Education: K-12 Program UpheldDocument3 pagesCoTesCUP v Sec. of Education: K-12 Program UpheldNico Deocampo100% (5)

- Commercialisation of EducationDocument20 pagesCommercialisation of EducationPramod Panwar100% (1)

- 3rd unitDocument41 pages3rd unitVibha VargheesNo ratings yet

- Law and Education MaterialDocument7 pagesLaw and Education MaterialAditya rathoreNo ratings yet

- Right Ho Elementary EducationDocument60 pagesRight Ho Elementary EducationShobha J PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Education For Social Change With Reference To Right To Education Act 2009 in IndiaDocument4 pagesEducation For Social Change With Reference To Right To Education Act 2009 in Indiasrik1011No ratings yet

- RTE Avinash Mehrotra V Union of India & Other 2017 en 0Document3 pagesRTE Avinash Mehrotra V Union of India & Other 2017 en 0Jayant100% (1)

- Is Setting Up and Running A Private Educational Institution Protected Under Articles 19Document16 pagesIs Setting Up and Running A Private Educational Institution Protected Under Articles 19Indulekha SreekumarNo ratings yet

- Seminar Right To Education.Document4 pagesSeminar Right To Education.Trupti DabkeNo ratings yet

- Right To Free and Compulsory EducationDocument8 pagesRight To Free and Compulsory EducationkunishkaNo ratings yet

- Dream Universal Elementary EducationDocument88 pagesDream Universal Elementary EducationShobha J PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Judiciary's Role in Developing India's Education SystemDocument2 pagesJudiciary's Role in Developing India's Education SystemKumar SpandanNo ratings yet

- RTE ACTDocument19 pagesRTE ACTsandeepNo ratings yet

- Universal Elementary EducationDocument100 pagesUniversal Elementary EducationH.J.PrabhuNo ratings yet

- FactsDocument4 pagesFactsnikhil singhNo ratings yet

- 4as Framework in Right To Education: A Critical AnalysisDocument8 pages4as Framework in Right To Education: A Critical AnalysisAnonymous CwJeBCAXp50% (2)

- Society For Unaided Private Schools of RDocument12 pagesSociety For Unaided Private Schools of RAkAsh prAkhAr vErmANo ratings yet

- Ihrc School Enrolment Policy Submission October 2011Document19 pagesIhrc School Enrolment Policy Submission October 2011mrgallagher.deanNo ratings yet

- M.M. Public School Discusses India's Right to Education ActDocument12 pagesM.M. Public School Discusses India's Right to Education ActSanchit RajaNo ratings yet

- Right To Education Act 2009Document10 pagesRight To Education Act 2009Pale LuckyNo ratings yet

- Education Law AssignmentDocument4 pagesEducation Law AssignmentCrampy GamingNo ratings yet

- Academic Freedom: XIV. EducationDocument18 pagesAcademic Freedom: XIV. EducationDevilleres Eliza DenNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2308296Document6 pagesIJCRT2308296Jonus D’souzaNo ratings yet

- Right To EducationDocument26 pagesRight To Educationjyoti_drall08No ratings yet

- Right To EducationDocument7 pagesRight To EducationMehvash ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Right To Education ActDocument28 pagesRight To Education ActMugdha Tomar100% (1)

- Right To Education: Presented by - Akriti PradhanDocument59 pagesRight To Education: Presented by - Akriti PradhanArpita PradhanNo ratings yet

- Article 21A - Constitutional LawDocument3 pagesArticle 21A - Constitutional LawAamir harunNo ratings yet

- Education Law by Malik Aamir SLC 2023Document28 pagesEducation Law by Malik Aamir SLC 2023coldheatkingNo ratings yet

- Constitution Law - Article 21 - ADocument19 pagesConstitution Law - Article 21 - AShelly AroraNo ratings yet

- CONSTI POLICY REVIEWDocument8 pagesCONSTI POLICY REVIEWTanya YadavNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Right of Childen To Free and Compulsory Education ActDocument7 pagesA Comparative Study of Right of Childen To Free and Compulsory Education ActShivam JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Right to Education Fundamental in IndiaDocument26 pagesRight to Education Fundamental in IndiaAnutosh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Right To EducationDocument7 pagesRight To Educationruman ahmadNo ratings yet

- Education as a Fundamental Right in IndiaDocument2 pagesEducation as a Fundamental Right in IndiaBhakti AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Education Tribunal Bill, 2010 - CommentDocument3 pagesEducation Tribunal Bill, 2010 - CommentShradha BaranwalNo ratings yet

- Edu Law U1 by Fakhrul XamaaanDocument11 pagesEdu Law U1 by Fakhrul Xamaaanfxmn001No ratings yet

- Right To Education Act 2009Document11 pagesRight To Education Act 2009Rda ChhangteNo ratings yet

- Right To Education Bill 2005Document44 pagesRight To Education Bill 2005raveenkumarNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, LucknowDocument14 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, LucknowStuti SinhaNo ratings yet

- AVINASH MEHROTRA Vs UNION OF INDIADocument2 pagesAVINASH MEHROTRA Vs UNION OF INDIACrampy GamingNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document3 pagesCase Study 2Stuti BaradiaNo ratings yet

- Unit 7: UGC and Bodies Under UGC: by Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument6 pagesUnit 7: UGC and Bodies Under UGC: by Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Unit 1.4 UNO SPECIALISED AGENCYDocument9 pagesUnit 1.4 UNO SPECIALISED AGENCYTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Right of Children To Free AND Compulsor Y Education A C T, 2 0 0 9Document9 pagesRight of Children To Free AND Compulsor Y Education A C T, 2 0 0 9Trinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Women and Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument8 pagesWomen and Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Right to Education in 40 CharactersDocument11 pagesRight to Education in 40 CharactersTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Privatization of Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument5 pagesPrivatization of Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- National Education Policy, 1986: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument14 pagesNational Education Policy, 1986: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Secondary Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument10 pagesSecondary Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Problem of Higher Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument4 pagesProblem of Higher Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- NEP2020GoalsQualityEducationDocument6 pagesNEP2020GoalsQualityEducationTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- ADULT Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument9 pagesADULT Education: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- NEP2020GoalsQualityEducationDocument6 pagesNEP2020GoalsQualityEducationTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- IRAC8897Document2 pagesIRAC8897Navaneeth NeonNo ratings yet

- IRAC8897Document2 pagesIRAC8897Navaneeth NeonNo ratings yet

- MCQ TEST SUBJECT - PROPERTY LAW Date - 09.10.21 DAY - Saturday TIME - 10 - 40 Am - 11 - 30 AmDocument6 pagesMCQ TEST SUBJECT - PROPERTY LAW Date - 09.10.21 DAY - Saturday TIME - 10 - 40 Am - 11 - 30 AmTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- CONSTITUTIONAL LAW GROUP: LAW ON EDUCATIONDocument215 pagesCONSTITUTIONAL LAW GROUP: LAW ON EDUCATIONTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- National Education Policy, 1986: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatDocument14 pagesNational Education Policy, 1986: Rahi Ajabe-AlhatTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law II FederalismDocument7 pagesConstitutional Law II FederalismTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Maternity BenefitsDocument8 pagesMaternity BenefitsTrinity NagpalNo ratings yet

- Sma13 4152 PDFDocument268 pagesSma13 4152 PDFTony TorresNo ratings yet

- Chinmay Kalgaonkar - Reformation, Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Juvenile in Conflict With LawDocument20 pagesChinmay Kalgaonkar - Reformation, Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Juvenile in Conflict With LawChinmay KalgaonkarNo ratings yet

- Child marriage and gender inequality amid COVID-19Document2 pagesChild marriage and gender inequality amid COVID-19Anonymous AnonymousNo ratings yet

- Mrs Mardini refugee status assessmentDocument9 pagesMrs Mardini refugee status assessmentJeff SeaboardsNo ratings yet

- Installation of CCTV Cameras ProposalDocument2 pagesInstallation of CCTV Cameras ProposalJojirose Anne Bernardo Monding100% (1)

- Presumption in Dowry Death Cases Under Section 113BDocument14 pagesPresumption in Dowry Death Cases Under Section 113BChoudhary Shadab phalwanNo ratings yet

- Developmental Social Welfare PP PresDocument13 pagesDevelopmental Social Welfare PP PresDeanne AgduyengNo ratings yet

- Bail and Bond in Zambia: Challenges and Recommendations Considering Legal and Administrative ReformsDocument15 pagesBail and Bond in Zambia: Challenges and Recommendations Considering Legal and Administrative ReformsMinz PatelNo ratings yet

- Child AbuseDocument2 pagesChild AbuseseserNo ratings yet

- R.A. 7192 - Breakdown With QuestionsDocument2 pagesR.A. 7192 - Breakdown With QuestionsCarlou Manzano100% (2)

- Annual Youth Program Promotes Health, Education and EmpowermentDocument9 pagesAnnual Youth Program Promotes Health, Education and EmpowermentRene DelovioNo ratings yet

- Order of Nine Angles NexionDocument28 pagesOrder of Nine Angles NexionGabriel Ferracini DonegáNo ratings yet

- Comparative Policing Chapter 1 - Part 3Document5 pagesComparative Policing Chapter 1 - Part 3Magr EscaNo ratings yet

- Social WorkerDocument36 pagesSocial WorkerDanielah SalubreNo ratings yet

- Grand Chamber: Case of Bouyid V. BelgiumDocument44 pagesGrand Chamber: Case of Bouyid V. BelgiumEseosa EnorenseegheNo ratings yet

- Flores Shinshillas Race and Gender Action Plan Elrc 7600Document4 pagesFlores Shinshillas Race and Gender Action Plan Elrc 7600api-599630228No ratings yet

- Answer Sheet Gegd 2Document15 pagesAnswer Sheet Gegd 2Stephany Joy M. MendezNo ratings yet

- Juvenile DelinquencyDocument3 pagesJuvenile DelinquencyLhena EstoestaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Discrimination Bill 2.0 (HB 3432)Document10 pagesAnti-Discrimination Bill 2.0 (HB 3432)Jonas Bagas0% (1)

- Americans and Cancel CultureDocument21 pagesAmericans and Cancel CultureAro ItoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Human RightsDocument8 pagesUnderstanding Human RightsBandhuka KuruppuNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Sexual Violence and Subhuman Conditions: The Case of Bosnia and RwandaDocument11 pagesThe Politics of Sexual Violence and Subhuman Conditions: The Case of Bosnia and RwandaTraditional Journal of Law and Social SciencesNo ratings yet

- Feminism Still DireDocument34 pagesFeminism Still DireAnju singh0% (1)

- 1619 Project The Idea of America Part 1Document20 pages1619 Project The Idea of America Part 1api-593462252No ratings yet

- The Relationship: Between Businesses and Human RightsDocument8 pagesThe Relationship: Between Businesses and Human RightsAndrew BantiloNo ratings yet

- People who experienced sleep paralysisDocument7 pagesPeople who experienced sleep paralysisAva BarramedaNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Kidnapping From Lawful Guardianship andDocument3 pagesDifference Between Kidnapping From Lawful Guardianship andJanhvi PrakashNo ratings yet

- Group3chapter1 3Document32 pagesGroup3chapter1 3Donita BernardinoNo ratings yet

- Population Control BillDocument3 pagesPopulation Control BillSanketNo ratings yet

- Chapter: 1 Introduction: Context For ResearchDocument20 pagesChapter: 1 Introduction: Context For ResearchSTAR PRINTINGNo ratings yet