Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Mad Russian

Uploaded by

Bob Ross0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

67 views7 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

67 views7 pagesThe Mad Russian

Uploaded by

Bob RossCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

mvmagazine.

com

The Mad Russian

Kib Bramhall

10-12 minutes

8.31.11

Sergei de Somov was legendary in Island

fishing circles. Artist and fellow angler Kib

Bramhall writes about the three-time Derby

winner in his new book, Bright Waters, Shining

Tides: Reflections on a Lifetime of Fishing.

A night for bass.

The rising tide laps softly against a rock-strewn beach,

while beyond the swelling breakers the ocean is rippled

by a gentle onshore breeze. The pale glow of a waning

moon filters through the misty dark, punctuated by

mysterious cloud shapes that drift across the sky like

apparitions. Bait fish rustle nervously in the wash of a

deep hole formed by the movement of tides and waves

through a break in the offshore sandbar.

A mile to the west and a half mile off the beach, a pod of

large stripers moves out of a dying tide rip, slowly

following the current, heading toward the surf.

At the same moment, four miles inland, a wraith-like

figure emerges from the doorway of a shingled cottage

and ghosts through the darkness to a Jeep concealed

behind nearby foliage. It has already been loaded with

heavy-duty surf tackle, an assortment of customized

lures with hooks filed to pinpoint sharpness, waders,

gaff, billy, a container of live eels, and perhaps some

lobster meat for gourmet bass bait. The engine coughs,

shattering the night’s stillness.

Sergei de Somov, the famed Mad Russian of the

Northeast striper coast, moves toward another

rendezvous with his prey.

It is the hour before dawn, and the pod of bass is

moving faster now, almost with a sense of urgency. As

they reach the break in the offshore bar, several of the

fish swim through into the deep hole, warily at first and

then with a surge. These forerunners move into the

wash of the surf, and the rest follow. Thousands of bait

fish panic as big stripers move in for the kill.

Minutes earlier a blacked-out Jeep had coasted to a

stop behind a dune overlooking this hole. The beach is

deserted except for the figure moving from the vehicle

toward the surf.

It is no accident or stroke of luck that Sergei has come

to this particular stretch of beach at a magic hour when

trophy bass have arrived for a predawn breakfast. His

trip had been planned with scientific precision that took

into account many factors: wind direction on that day

and several days previous; tidal stage and direction of

flow; the amount of bait along this beach and in

adjacent waters; recent and past patterns of striper

movement and behavior in this area; water conditions,

including clarity, temperature, and roughness; the hour

itself.

All these things had been observed and weighed with

penetrating Russian logic and an answer arrived at.

Sergei’s eyes sparkle, and a wide grin creases his face.

He knows his decision was right. Bait fish are being

driven high onto the beach by the marauding bass, and

the swirls of big fish can be seen in the eerie moon mist.

The long surf rod is swept back to make the first cast

– but wait!

Headlights bob over the horizon half a mile down the

beach. A vehicle has turned off the access road onto the

sand and is driving toward him. Sergei swiftly retraces

his steps to the concealment of the dune and watches

as it stops a couple of hundred yards away. Dim figures

emerge, spread out, and start probing the surf. False

dawn has nearly arrived, and Sergei might be seen if he

goes back to those bass. He has only one alternative,

and he takes it without hesitation. The rod is racked, the

engine coughs, and with lights still extinguished he

vanishes down the beach.

Has this expedition been a maddening failure? Not

completely. Not to the Mad Russian. It was galling, of

course, that such careful plans had to be abandoned at

the very moment of consummation, but this was

balanced by his success at having avoided detection. It

had been a close call, but in the end no one had caught

so much as a glimpse of him. Those other anglers had

been unaware of his nearby presence. He had remained

a virtual phantom of the surf.

Well, it might have happened that way, and then again

maybe it didn’t. There is no way of knowing, because it

was im-possible to penetrate the closely guarded

secrecy that cloaked the Mad Russian’s surf-fishing

trips – secrecy that helped make this eccentric, brilliant

fisherman a legend in his own time.

Although Sergei’s methods, his nocturnal wanderings on

the striper coast, and his battles with outsized stripers

were shrouded in mystery, his exploits were not. For the

past two decades he had racked up eye-popping

catches on the beaches of Long Island and New Jersey,

as well as on the Vineyard. And that is what made him

such a compelling subject of speculation among the

hard-core fraternity of surf men. The courtly gentleman

with the foreign accent kept showing up with big

stripers, and no one knew exactly how, when, or where

he caught them.

Perhaps his most astounding accomplishments

occurred on Martha’s Vineyard during the Island’s

annual striped bass and bluefish derbies. These month-

long autumn contests attract thousands of participants,

including many of the most skilled surf fishermen on the

Northeast coast. For three consecutive years – in 1963,

1964, and 1965 – Sergei took on all competitors and

won top honors for the largest striper (with fish of fifty-

two pounds, thir-teen ounces; fifty-four pounds, fourteen

ounces; and forty-nine pounds, ten ounces). No one else

has matched that achievement in the contest’s

venerable history.

Sergei de Somov was born on Christmas morning 1896

in St. Petersburg, Russia. His father was in the

diplomatic service, and Sergei gained working

knowledge of eight languages during his cosmopolitan

upbringing. After graduating from college he became a

member of Her Majesty’s Imperial Lancers and rose to

the rank of major. He immigrated to the United States in

1923 and settled in New York City, where he taught

school, then worked on Wall Street, moved to the Edison

Company, and finally joined the National Broadcasting

Company in 1929, where he worked for the next

nineteen years.

The salt air and sea beckoned, and in the early 1930s

Sergei moved to Long Island, where he joined the East

End Surf Fishing Club. From that time forward, the

angling world began hearing colorful tales of piscatorial

prowess, of strange homemade lures, of occult

nocturnal fishing trips, of an elusive foreign gentleman

who consistently beached big striped bass – always

while fishing alone.

The beginnings of Sergei’s fishing career were as exotic

as his methods were bizarre. In 1911, when he was

fifteen years old, his father introduced him to the fine art

of angling on the Hangang River in Korea, where the

elder de Somov was stationed as a representative of his

country’s government. The quarry? Korean fahak, or

blowfish. The tackle? Spinning, decades before it made

its appearance in this country.

In spite of having been weaned on spinning tackle,

Sergei had no love for it when I knew him in the 1950s

and ’60s on the Vineyard. A surf spinning outfit was a

“yo-yo” rig as far as he was concerned, perfectly okay

for small fish, but not adequate for the trophy bass that

were his quarry. For these he used heavy-duty

conventional tackle: rods with stiff backbone and

revolving spool reels filled with a minimum forty-five-

pound-test Dacron braid tied directly to his lures. When

he thought there was a chance for a record striper, he

upgraded to his “man-killer” rig – a Herculean rod

mounting an oversized reel spooled with eighty-pound

test. He was only interested in catching big bass.

Schoolies were “nuisance fish.”

He made many of his own lures, but he caught one of

his Vineyard Derby winners on a plug that he had

borrowed from me. It was a big swimming plug called

the Sea Serpent, which was armed with two large, extra-

strong single hooks. It was made in Germany and

designed to catch tuna on the North African coast. I saw

it in a tackle store in Paris and brought it back to the

Vineyard to use on striped bass. I showed it to Sergei,

who said, “Ah, Kib, that is a very serious plug. May I

borrow it?” Of course I loaned it to him, and he gave me

a photo of his winning bass with it in its mouth. The plug

itself, however, I never saw again.

Sergei was seventy years old when I got to know him in

1963. He was of medium height and appeared slight in

physique, and I wondered how he could wield such

heavy tackle until we shook hands. He had a grip like a

professional football player. He kept himself in superb

physical condition, walking countless miles along the

beach, observing water and topographical conditions

every step of the way. He tested water temperatures and

took note of holes and hidden bars, of water clarity, of

bait fish, of gull behavior, and then sifted and stored the

data with scientific thoroughness. When he decided

– and the decision was nevercasual – that all

indications pointed favorably to the likelihood of big

stripers visiting a certain stretch of surf, only then did he

make plans to be there too. And, of course, such plans

were always contingent upon his being able to fish

alone and unobserved, except for his wife, Louise, who

was an excellent angler in her own right, and with whom

he conversed in French, Russian, and English – all in the

same sentence.

The Mad Russian was a topic of conversation wherever

surf men gathered on the Northeast striper coast. His

skill at beaching big bass would, by itself, have been

enough to ensure his fame. The added elements of

secrecy and continental politesse enhanced it tenfold.

Many regarded him with awe akin to that commanded

by the ancient deities. Others simply respected him. A

jealous few protested that his skills were no more than

ordinary, and that his elusive tactics were merely

designed to mask the fact. But there is no disputing that

he was and remains a legend. He added an aura of

mystique to a sport that too many of us allow to enter

the realm of the prosaic, and he brought a touch of

poetry to the world of the high surf. It was a better place

because of it. Sergei was inducted into the Derby Hall of

Fame in 1999.

This is an excerpt from Bright Waters, Shining Tides:

Reflections on a Lifetime of Fishing (Vineyard Stories,

2011). One of eleven essays in the book, this is an

amended version of “Phantom in the Surf,” published in

Salt Water Sportsman (March 1967).

You might also like

- The Best of Jules Verne: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and The Mysterious IslandFrom EverandThe Best of Jules Verne: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and The Mysterious IslandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Pnaas 277Document375 pagesPnaas 277Bob RossNo ratings yet

- Storm Tide: A Novel of the American Revolution (Courtney, Book 20)From EverandStorm Tide: A Novel of the American Revolution (Courtney, Book 20)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Among The Mermaids Excerpt 9781578635450Document46 pagesAmong The Mermaids Excerpt 9781578635450VarlaVenturaNo ratings yet

- Flaws in India's Coal Allocation ProcessDocument12 pagesFlaws in India's Coal Allocation ProcessBhaveen JoshiNo ratings yet

- The Girl in Room 105 Is The Eighth Novel and The Tenth Book Overall Written by The Indian Author Chetan BhagatDocument3 pagesThe Girl in Room 105 Is The Eighth Novel and The Tenth Book Overall Written by The Indian Author Chetan BhagatSiddharrth Prem100% (1)

- Gloucester on the Wind: America's Greatest Fishing Port in the Days of SailFrom EverandGloucester on the Wind: America's Greatest Fishing Port in the Days of SailNo ratings yet

- Example - Summons Automatic Rent Interdict High CourtDocument8 pagesExample - Summons Automatic Rent Interdict High Courtkj5vb29ncqNo ratings yet

- Bermuda TriangleDocument13 pagesBermuda TrianglepradeepsatpathyNo ratings yet

- Cold Grave: An unsolved crime; a tide of secrets suddenly and shockingly unleashed ...From EverandCold Grave: An unsolved crime; a tide of secrets suddenly and shockingly unleashed ...Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- A Disaster Recovery Plan PDFDocument12 pagesA Disaster Recovery Plan PDFtekebaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Equity Analysis of Selected Banking StocksDocument109 pagesA Study On Equity Analysis of Selected Banking Stocksanil0% (1)

- The Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanFrom EverandThe Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanNo ratings yet

- The Story of Sitka: The Historic Outpost of the Northwest Coast; The Chief Factory of the Russian American CompanyFrom EverandThe Story of Sitka: The Historic Outpost of the Northwest Coast; The Chief Factory of the Russian American CompanyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Mysterious Disappearance of the Mary CelesteDocument25 pagesThe Mysterious Disappearance of the Mary Celesteinge92No ratings yet

- Landfall: Islands in the Aftermath: The Pulse Series, #4From EverandLandfall: Islands in the Aftermath: The Pulse Series, #4Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Letter of Motivation (Financial Services Management)Document1 pageLetter of Motivation (Financial Services Management)Tanzeel Ur Rahman100% (5)

- Fire on the Beach: Recovering the Lost Story of Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island LifesaversFrom EverandFire on the Beach: Recovering the Lost Story of Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island LifesaversRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Fm-Omcc-Psc-021 Terminal and Routine Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection Checklist.Document2 pagesFm-Omcc-Psc-021 Terminal and Routine Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection Checklist.Sheick MunkNo ratings yet

- Going Fishing: Travel and Adventure with a Fishing RodFrom EverandGoing Fishing: Travel and Adventure with a Fishing RodRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Tales of Fishes: "The sun lost its heat, slowly slanted to the horizon of mangroves, and turned red."From EverandTales of Fishes: "The sun lost its heat, slowly slanted to the horizon of mangroves, and turned red."No ratings yet

- Surf PlugologyDocument63 pagesSurf Plugologyez2cdaveNo ratings yet

- Through the South Seas with Jack London With an introduction and a postscript by Ralph D. Harrison. Numerous illustrations.From EverandThrough the South Seas with Jack London With an introduction and a postscript by Ralph D. Harrison. Numerous illustrations.No ratings yet

- Piebald Dog Running Along The Shore by Chingiz AitmatovDocument38 pagesPiebald Dog Running Along The Shore by Chingiz Aitmatovsursri2002No ratings yet

- Hard Rivers: The Untold Saga of La Salle: Expedition IIFrom EverandHard Rivers: The Untold Saga of La Salle: Expedition IIRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Surfmen and Shipwrecks: Spirits of Cape Hatteras IslandFrom EverandSurfmen and Shipwrecks: Spirits of Cape Hatteras IslandNo ratings yet

- Bram Stoker - The Mystery Of The Sea: “No one but a woman can help a man when he is in trouble of the heart.”From EverandBram Stoker - The Mystery Of The Sea: “No one but a woman can help a man when he is in trouble of the heart.”No ratings yet

- Riverfront Marine Sports: Tis The Season For ShrinkageDocument7 pagesRiverfront Marine Sports: Tis The Season For ShrinkageKFMediaNo ratings yet

- Wells HG - The Sea Raiders - GEDocument8 pagesWells HG - The Sea Raiders - GEVKNo ratings yet

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (World Classics, Unabridged)From EverandTwenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (World Classics, Unabridged)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (62)

- Stories of Ships and The Sea Little Blue Book # 1169 by London, Jack, 1876-1916Document32 pagesStories of Ships and The Sea Little Blue Book # 1169 by London, Jack, 1876-1916Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Bomag bpr65 70Document22 pagesBomag bpr65 70jeremyduncan090185iqk100% (126)

- ExtractedDocument148 pagesExtractedtendoesch1994No ratings yet

- Abandoned Ship MysteryDocument2 pagesAbandoned Ship MysteryAnju AnitaNo ratings yet

- Swados RobinsonCrusoeMan 1958Document17 pagesSwados RobinsonCrusoeMan 1958arifulislam373197No ratings yet

- W. H. Elliot,: RevolverDocument3 pagesW. H. Elliot,: RevolverBob RossNo ratings yet

- Frame repair splicing methodsDocument9 pagesFrame repair splicing methodsBob RossNo ratings yet

- Rust Removal ElecDocument2 pagesRust Removal ElecJinjinkas100% (1)

- Cement MixerDocument3 pagesCement MixerGreg Phillpotts100% (5)

- Tides 2022Document4 pagesTides 2022Bob RossNo ratings yet

- Rear body flat bed diagramsDocument11 pagesRear body flat bed diagramsBob RossNo ratings yet

- 8 71 Compressor Air CondiDocument3 pages8 71 Compressor Air CondiBob RossNo ratings yet

- Novices'Corner: Using The D-BitDocument3 pagesNovices'Corner: Using The D-BitBob RossNo ratings yet

- 8 65 Control Lever HeaterDocument3 pages8 65 Control Lever HeaterBob RossNo ratings yet

- 03 Plastic-PoppersDocument3 pages03 Plastic-PoppersBob RossNo ratings yet

- Owner Builder Study Guide PDFDocument60 pagesOwner Builder Study Guide PDFDarigan194No ratings yet

- Lightweight PoppersDocument2 pagesLightweight PoppersBob RossNo ratings yet

- 15 Plug - Building - ConclusionDocument2 pages15 Plug - Building - ConclusionBob RossNo ratings yet

- Darter Banana Eel DiverDocument14 pagesDarter Banana Eel DiverBob RossNo ratings yet

- Automotive Test Probe ConstructionDocument4 pagesAutomotive Test Probe ConstructionLy Fotoestudio DigitalcaNo ratings yet

- Coral SEA: Ally SM Ooth and SM Ooth WatersDocument1 pageCoral SEA: Ally SM Ooth and SM Ooth WatersBob RossNo ratings yet

- Slider SkipperDocument2 pagesSlider SkipperBob RossNo ratings yet

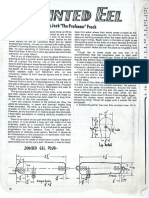

- Jointed EelDocument2 pagesJointed EelBob RossNo ratings yet

- Storage System For Nuts and BoltsDocument2 pagesStorage System For Nuts and BoltsBob RossNo ratings yet

- Micrometer Torque Wrench: Case 3wayDocument4 pagesMicrometer Torque Wrench: Case 3wayBob RossNo ratings yet

- IndexDocument2 pagesIndexAlexendra100% (1)

- Manual Transmission (MSG Models) PDFDocument46 pagesManual Transmission (MSG Models) PDFHartok100% (1)

- Act 4103 - The Indeterminate Sentence LawDocument3 pagesAct 4103 - The Indeterminate Sentence LawRocky MarcianoNo ratings yet

- Water Resources in TamilnaduDocument4 pagesWater Resources in TamilnaduVignesh AngelNo ratings yet

- Yongqiang - Dealing With Non-Market Stakeholders in The International MarketDocument15 pagesYongqiang - Dealing With Non-Market Stakeholders in The International Marketisabelle100% (1)

- ENGLISH - Radio Rebel Script - DubbingDocument14 pagesENGLISH - Radio Rebel Script - DubbingRegz Acupanda100% (1)

- Herb Fitch 1993 Chicago SeminarDocument131 pagesHerb Fitch 1993 Chicago SeminarLeslie BonnerNo ratings yet

- PIMENTELDocument5 pagesPIMENTELChingNo ratings yet

- Final ProposalDocument3 pagesFinal ProposalMadhurima GuhaNo ratings yet

- BankingDocument19 pagesBankingPooja ChandakNo ratings yet

- Acca Timetable June 2024Document13 pagesAcca Timetable June 2024Anish SinghNo ratings yet

- Tatmeen - WKI-0064 - Technical Guide For Logistics - v3.0Document88 pagesTatmeen - WKI-0064 - Technical Guide For Logistics - v3.0Jaweed SheikhNo ratings yet

- 8 Critical Change Management Models To Evolve and Survive - Process StreetDocument52 pages8 Critical Change Management Models To Evolve and Survive - Process StreetUJJWALNo ratings yet

- McDonald's Corporation Future in a Changing Fast Food IndustryDocument29 pagesMcDonald's Corporation Future in a Changing Fast Food IndustryKhor Lee KeanNo ratings yet

- Ôn tập ngữ pháp Tiếng Anh cơ bản với bài tập To V VingDocument10 pagesÔn tập ngữ pháp Tiếng Anh cơ bản với bài tập To V Vingoanh siuNo ratings yet

- Irb Ar 2012-13Document148 pagesIrb Ar 2012-13Shikhin GargNo ratings yet

- General TermsDocument8 pagesGeneral TermsSyahmi GhazaliNo ratings yet

- Los Del Camino #5 (Inglés)Document8 pagesLos Del Camino #5 (Inglés)benjaminNo ratings yet

- Punjab National Bank Punjab National Bank Punjab National BankDocument1 pagePunjab National Bank Punjab National Bank Punjab National BankHarsh ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence: by Mary Jane L. Molina RPH, MspharmDocument17 pagesJurisprudence: by Mary Jane L. Molina RPH, MspharmRofer ArchesNo ratings yet

- Qualys Gav Csam Quick Start GuideDocument23 pagesQualys Gav Csam Quick Start GuideNurudeen MomoduNo ratings yet

- The Impact of COVID-19 On Toyota Group Automotive Division and CountermeasuresDocument8 pagesThe Impact of COVID-19 On Toyota Group Automotive Division and CountermeasuresDâu TâyNo ratings yet

- Lecture Taxation of PartnershipDocument10 pagesLecture Taxation of PartnershipaliaNo ratings yet

- Procedures For Connection of PV Plants To MEPSO Grid in North MacedoniaDocument17 pagesProcedures For Connection of PV Plants To MEPSO Grid in North MacedoniaAleksandar JordanovNo ratings yet

- G47.591 Musical Instrument Retailers in The UK Industry Report PDFDocument32 pagesG47.591 Musical Instrument Retailers in The UK Industry Report PDFSam AikNo ratings yet