Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kellogg 6 Hours

Uploaded by

Yanisa RongkasiriphanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kellogg 6 Hours

Uploaded by

Yanisa RongkasiriphanCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Reviewed Work(s): Kellogg's Six-Hour Day by Benjamin Kline Hunnicutt

Review by: Ellen Mutari

Source: Review of Social Economy , WINTER 1998, Vol. 56, No. 4, SPECIAL ISSUE ON THE

SOCIAL ECONOMICS OF WORK TIME (WINTER 1998), pp. 543-546

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/29769980

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Review of Social Economy

This content downloaded from

131.173.88.37 on Sat, 06 Nov 2021 13:26:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REVIEW OF SOCIAL ECONOMY

Book Reviews

Kellogg's Six-Hour Day. By Benjamin Kline Hunnicutt. Philadelphia:

Temple University Press, 1996,261 pp., $24.96 paperback.

"Only an idiot would think you can get as much working less instead of more

hours a week," declared a Kellogg worker interviewed for this study in 1989 (53).

During the postwar period, U.S. workers have perceived themselves as facing a

choice between wages and shorter hours ? and most have chosen wages. In this

insightful book, Hunnicutt argues forcefully against the way that this choice has

been constructed. He uses a case study of 6-hour shifts at the Kellogg's company

in Battle Creek, Michigan, to illustrate the trend away from shorter hours in the

twentieth century. Four 6-hour shifts replaced three 8-hour shifts for nearly all of

the plant's departments in 1930, specifically as a work-sharing measure in

response to the onset of the Great Depression. Hourly wages were increased so

that workers would not bear the cost of work sharing. The policy was gradually

repealed during the postwar period, though some workers continued to cherish

shorter shifts until 1985.

W.K. Kellogg, the creator (along with older brother John Harvey Kellogg) of

the corn flake, did not accept the conventional wisdom expressed by the

contemporary worker quoted above. In 1935, he asserted:

We have found that, with the shorter working day, the efficiency and morale of our

employees is [sic] so increased, the accident and insurance rates are so improved,

and the unit cost of production is so lowered that we can afford to pay as much for

six hours as we formerly paid for eight (35).

Hunnicutt is less concerned with empirical evidence substantiating or

contradicting Kellogg's claim than with the changing consciousness of workers

themselves.

Review of Social Economy Vol LVI No. 4 Winter 1998 ISSN 0034 6764

? 1998 The Association for Social Economics

This content downloaded from

131.173.88.37 on Sat, 06 Nov 2021 13:26:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REVIEW OF SOCIAL ECONOMY

Kellogg's philosophy exemplifies "Liberation Capitalism," according to the

author. He defines Liberation Capitalism as a belief that economic progress and

productivity increases would result in the satisfaction of human necessities. This

would enable humans to spend less time at paid employment and to have the

freedom to engage in more fulfilling forms of activity. Thus, proponents of this

philosophy believed that the U.S. was entering an "Age of Leisure."

This vision was undermined by a "New Economic Gospel of Consumption"

during the post-war period. The political and economic coalition that emerged

during the New Deal emphasized the goal of continuous economic expansion and

work creation. As noted by Hunnicutt, "Jobs, Jobs, Jobs" became the watchword

of political campaigns. Economic growth was predicated upon "perpetual

consumerism and ever-expanding needs" (120). Hunnicutt argues that this

resulted from a cultural shift as much as from political and economic forces.

Chapters 1 and 2 provide an overview of these theoretical issues, drawing upon

the themes developed in Hunnicutt's previous book, Work Without End:

Abandoning Shorter Hours for the Right to Work (Temple University Press,

1988). Chapter 1 also provides insight into the key actors who instituted the work

sharing policy at Kellogg's. At first, a majority of workers embraced the policy, as

demonstrated by archival sources and retrospective interviews described in

Chapter 3. While this support was in part motivated by an ethical commitment to

job sharing during the economic crisis, workers also appreciated the freedom and

opportunity to pursue family and community activities. Kellogg himself

encouraged and sponsored leisure activities such as gardening, community sports,

libraries, and culture. The interviews reveal that the workers themselves disputed

Kellogg's claim that weekly wages did not fall, although most were satisfied with

the trade-off.

The heart of the book (chapters 4 through 7) describes the unraveling of the

shorter-hours policy. After the plant unionized in late 1936, W.K. Kellogg

withdrew from the daily management of the company. The new managers lacked

his paternalistic vision. After World War II, a labor-management coalition

increasingly supported a return to 8-hour shifts and cuts in the work force, coupled

with higher hourly wages. Male-dominated departments were at the forefront of

this coalition. The union, led by male workers in relatively high-paid jobs,

pursued bread-and-butter wage increases and the expansion of "full-time work."

Hunnicutt eloquently describes how the shorter work shifts were gradually

"feminized," that is, viewed as the province of women, the infirm, and older

workers. The hours discrepancy was used to justify gender-based wage

disparities. In the mid-1970s, some of the women workers, with the support of

local feminist organizations, brought a lawsuit protesting hours distinctions as a

form of gender discrimination. The company opened up jobs in the 8-hour

544

This content downloaded from

131.173.88.37 on Sat, 06 Nov 2021 13:26:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BOOK REVIEWS

departments to women applicants but deflected the issue of comparable hourly

wages. However, the departments with six-hour shifts remained female

dominated enclaves.

Eventually, according to Hunnicutt, leisure itself became feminized. The

cultural value of work increased, while leisure became synonymous with passive

consumption. Paid work was central to the identity of the male workers

interviewed. Only a minority of workers, mostly female, continued to defy efforts

to institute 8-hour shifts plant-wide. Hunnicutt labels them the "Six-Hour

Mavericks" (Chapter 8). Ironically, it was another major economic dislocation?

the wave of downsizing and capital flight of the early 1980s?that finally ended

the last of the 6-hour shifts. In Chapter 9, Hunnicutt (too briefly) describes how

Kellogg management used competitive pressures and the threat of relocation to

achieve this.

Part of the outstanding Temple University Press series on "Labor and Social

Change," Kellogg 's Six-Hour Day documents an important story in labor history.

The Kellogg case study is used to raise significant issues about the meaning of

work and other activities in peoples' lives. Hunnicutt uses both his own interviews

and others conducted by the U.S. Women's Bureau in 1932 to vividly illustrate

how the discourse about work has changed. In so doing, he challenges the primacy

of "economic man and woman" at the heart of labor economics, that is, economic

actors motivated by their desire for consumption goods. Further, he maintains that

the primacy of work as a source of identity is recent and problematic. Instead,

Hunnicutt calls for a return to valuing "leisure," distinguished from work by being

"free time" under the control of the individual. This time is actively lived, not

passively spent, as in joining a softball league rather than watching sports on

television.

Hunnicutt is a professor of leisure studies and thus views leisure as a "cultural

asset" (55). Part of his project is to contrast work as a realm of necessity and

leisure as a realm of freedom. Much of his discourse analysis focuses on this

contrast between freedom and necessity. However, his concept of work and

leisure could benefit from greater attention to the feminist literature on social

reproduction, especially the work of Nancy Folbre and Susan Himmelweit on

caring labor. Although he is careful to distinguish between men's and women's

major activities outside paid employment and extensively discusses the

importance of home duties and caregiving in women's lives, he is too facile in

constituting a clear divide between "work" and "leisure." Women do not

necessarily experience the household as a realm of freedom and control.

The story of the 6-hour day at Kelloggs ends in 1985, amid profound changes

in the Michigan industrial-based economy. Hunnicutt therefore misses the

opportunity to reflect upon the prospects for a revival of a shorter hours

545

This content downloaded from

131.173.88.37 on Sat, 06 Nov 2021 13:26:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REVIEW OF SOCIAL ECONOMY

movement. The shift in the labor movement and worker consciousness away from

shorter hours and towards high-wages and "full-time" employment was part of the

New Deal order that is now unraveling. Keynesian demand management, the

welfare state, and stable, unionized jobs (in some sectors, for some workers) were

all part and parcel of the Age of Consumption. To the extent these good, high

wage jobs are being replaced by poorer quality jobs, will workers reprioritize

toward seeking shorter work hours? Or has the commodification of leisure made

this unlikely? These questions might have strengthened the lesson of the book,

making it more than the recording of something now passed.

Nevertheless, this book is an important contribution to the interdisciplinary

literature on working time. Further, because it addresses fundamental issues about

the scope and purpose of economic activity, the nature of economic growth, and

the premises of conventional models of the labor market, this book should be of

interest to economists in a number of fields. Social economists will especially

appreciate the author's attention to the interaction between cultural values and

economic institutions.

Ellen Mutari

Monmouth University

Work and Idleness: The Political Economy of Full Employment. Series on

Recent Economic Thought. Edited by Jane Wheelock and John Vail. Boston/

Dordrecht/London: Kluwer, 1998, $99.95 hardcover.

This book is an ambitious attempt to survey thinking about work and idleness. The

contributions are equally split between economists and social policy analysts.

Following an introduction by the editors, the book is organized into respective

sections of different theoretical perspectives, evaluations of work among

demographic groups, and alternative blueprints for policy.

Chapter 2 by John Wells examines the determination of employment from a

Keynesian perspective. The chapter begins with an account of the neoclassical

(i.e. non-Keynesian) approach to labor markets which emphasizes their automatic

and rapid self-equilibrating properties. It then presents some recent developments

in this tradition that explain why labor markets may adjust slowly and exhibit

permanent involuntary unemployment. The cause of such unemployment lies not

with the individual worker but with structural features of the labor market. These

features include excessive trade union power which prevents wages from falling.

The policy focus of this new approach is labor market reform that aims to remove

structural impediments: this includes weakening unions and employment

546

This content downloaded from

131.173.88.37 on Sat, 06 Nov 2021 13:26:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Human Capital TheoryDocument14 pagesHuman Capital TheoryParameshwara AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Msod619 LunettesbookclubDocument8 pagesMsod619 Lunettesbookclubapi-352281578No ratings yet

- Corporate SR For Work Family BalanceDocument29 pagesCorporate SR For Work Family BalanceVitto CorleoneNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism, Governance and Development at The Land-Grant Complex in The Contemporary Era of Higher EducationDocument13 pagesNeoliberalism, Governance and Development at The Land-Grant Complex in The Contemporary Era of Higher EducationJohn GunnNo ratings yet

- Keynesian RevolutionDocument4 pagesKeynesian RevolutionRakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- From Manual Workers To Wage Laborers - Transformation of The SociDocument5 pagesFrom Manual Workers To Wage Laborers - Transformation of The Socistyvasio2055No ratings yet

- The Anthropology of Work and Labour: Editorial Note: January 2018Document12 pagesThe Anthropology of Work and Labour: Editorial Note: January 2018Marko StojanovićNo ratings yet

- Ted Talk SpeechDocument8 pagesTed Talk Speechapi-665595119No ratings yet

- The Paradigmatic Crisis in Chinese Studies: Paradoxes in Social and Economic HistoryDocument44 pagesThe Paradigmatic Crisis in Chinese Studies: Paradoxes in Social and Economic HistoryYadanarHninNo ratings yet

- Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and CareersFrom EverandGetting a Job: A Study of Contacts and CareersRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Temp Economy: From Kelly Girls to Permatemps in Postwar AmericaFrom EverandThe Temp Economy: From Kelly Girls to Permatemps in Postwar AmericaNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Work EthicsDocument4 pagesRethinking Work EthicsRizki TrisnasariNo ratings yet

- Ellen Meiksins Wood - Labor - The - State - and - Class - Struggle - Monthly - Review PDFDocument9 pagesEllen Meiksins Wood - Labor - The - State - and - Class - Struggle - Monthly - Review PDFOdraudeIttereipNo ratings yet

- The Working Class Majority: America's Best Kept SecretFrom EverandThe Working Class Majority: America's Best Kept SecretRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Stuff the Accord! Pay Up!: Workers' Resistance to the ALP-ACTU AccordFrom EverandStuff the Accord! Pay Up!: Workers' Resistance to the ALP-ACTU AccordNo ratings yet

- Multilateralism and Multipolarity: Structures of the Emerging World OrderFrom EverandMultilateralism and Multipolarity: Structures of the Emerging World OrderNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Handbook On Diverse Economies: Inventory As Ethical Intervention by J.K. Gibson-Graham and Kelly DombroskiDocument25 pagesIntroduction To The Handbook On Diverse Economies: Inventory As Ethical Intervention by J.K. Gibson-Graham and Kelly DombroskiPlábio Marcos Martins DesidérioNo ratings yet

- Consequences of Capitalism: Manufacturing Discontent and ResistanceFrom EverandConsequences of Capitalism: Manufacturing Discontent and ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Positive Consitutional Economics !Document44 pagesPositive Consitutional Economics !fgdNo ratings yet

- Brody 1985Document5 pagesBrody 1985Pedro RoqueteNo ratings yet

- A Critique of Approaches To 'Domesticwork' WomenDocument36 pagesA Critique of Approaches To 'Domesticwork' WomenElizabeth PinoNo ratings yet

- Resistance To Change - A Social Psychological PerspectiveDocument31 pagesResistance To Change - A Social Psychological PerspectiveHonda SevrajNo ratings yet

- Industrial Labor on the Margins of Capitalism: Precarity, Class, and the Neoliberal SubjectFrom EverandIndustrial Labor on the Margins of Capitalism: Precarity, Class, and the Neoliberal SubjectNo ratings yet

- Organizing at the Margins: The Symbolic Politics of Labor in South Korea and the United StatesFrom EverandOrganizing at the Margins: The Symbolic Politics of Labor in South Korea and the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Thesis LseDocument5 pagesThesis Lsegjggsf72100% (2)

- The Long Swings in Economic Understanding: Axel LeijonhufvudDocument32 pagesThe Long Swings in Economic Understanding: Axel LeijonhufvudArtur CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Wolfe 1955Document20 pagesWolfe 1955Shashank KumarNo ratings yet

- Shiller 2017Document58 pagesShiller 2017PeteNo ratings yet

- Leisure in The UK Across The 20th Century: January 2001Document38 pagesLeisure in The UK Across The 20th Century: January 2001AleeexNo ratings yet

- Eng Research 12Document4 pagesEng Research 12api-343594787No ratings yet

- The Rent-Seeking Society (V. 5) by Gordon TullockDocument346 pagesThe Rent-Seeking Society (V. 5) by Gordon TullockgezzNo ratings yet

- From The Entrepreneurial UniveDocument10 pagesFrom The Entrepreneurial UniveAnkita Vardhan JoshiNo ratings yet

- Development and Social Change A Global Perspective Book ReviewDocument2 pagesDevelopment and Social Change A Global Perspective Book ReviewEdenHeavNo ratings yet

- Working through the Past: Labor and Authoritarian Legacies in Comparative PerspectiveFrom EverandWorking through the Past: Labor and Authoritarian Legacies in Comparative PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- Revew of Great Powers and Geopolitical Change by JDocument6 pagesRevew of Great Powers and Geopolitical Change by JJau HameedNo ratings yet

- Globalization and The Labour Movement Challenges ADocument18 pagesGlobalization and The Labour Movement Challenges AMufthas RasikimNo ratings yet

- Creating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social ProgressFrom EverandCreating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social ProgressRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Economic Heresies Some Old Fashioned Questions in Economic Theory PDFDocument167 pagesEconomic Heresies Some Old Fashioned Questions in Economic Theory PDFWashington Quintero100% (1)

- Osiris, Volume 33: Science and Capitalism: Entangled HistoriesFrom EverandOsiris, Volume 33: Science and Capitalism: Entangled HistoriesNo ratings yet

- Buchwalter (Ed.) - Hegel and Capitalism (2015) PDFDocument234 pagesBuchwalter (Ed.) - Hegel and Capitalism (2015) PDFwolfgang.villarreal2984No ratings yet

- ConActually Existing Globalisation, Deglobalisation, and The Political Economy of Anticapitalist Protest Byray KielyDocument30 pagesConActually Existing Globalisation, Deglobalisation, and The Political Economy of Anticapitalist Protest Byray Kiely5705robinNo ratings yet

- Dominance and Leadership in The International EconomyDocument14 pagesDominance and Leadership in The International EconomyADuckNo ratings yet

- The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money After 75 YearsDocument24 pagesThe General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money After 75 YearsYadira AceroNo ratings yet

- In The Hu Jintao Era - Lam 2006Document376 pagesIn The Hu Jintao Era - Lam 2006Nikola HoškováNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Its Discontents: Possible Ways Forward For Labour MovementsDocument16 pagesGlobalization and Its Discontents: Possible Ways Forward For Labour Movementshadi ameerNo ratings yet

- Marc R. Tool (Auth.) - Value Theory and Economic Progress - The InstDocument233 pagesMarc R. Tool (Auth.) - Value Theory and Economic Progress - The InstRodrigoNo ratings yet

- Distrib y CrecimientoDocument16 pagesDistrib y CrecimientopolianobcNo ratings yet

- Duke University PressDocument21 pagesDuke University Presskay_elle_beeNo ratings yet

- Just Around The Corner: The Paradox Of The Jobless RecoveryFrom EverandJust Around The Corner: The Paradox Of The Jobless RecoveryNo ratings yet

- Economics for Democracy in the 21st Century: A Critical Review of Definition and ScopeFrom EverandEconomics for Democracy in the 21st Century: A Critical Review of Definition and ScopeNo ratings yet

- Retrieve 2Document33 pagesRetrieve 2p8hwvb52d7No ratings yet

- The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. IllustratedFrom EverandThe General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. IllustratedRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (18)

- Work, Workfare, Work/Life Balance and An Ethic of Care: Linda McdowellDocument19 pagesWork, Workfare, Work/Life Balance and An Ethic of Care: Linda McdowellHas StepanyanNo ratings yet

- DLL CW 7Document2 pagesDLL CW 7Bea67% (3)

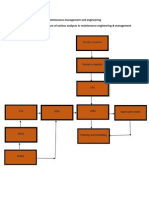

- Overview of MEMDocument5 pagesOverview of MEMTudor Costin100% (1)

- High Performance Vector Control SE2 Series InverterDocument9 pagesHigh Performance Vector Control SE2 Series InverterhanazahrNo ratings yet

- Bearing TypesDocument5 pagesBearing TypesWayuNo ratings yet

- OOPS KnowledgeDocument47 pagesOOPS KnowledgeLakshmanNo ratings yet

- Company Profile PT. Geo Sriwijaya NusantaraDocument10 pagesCompany Profile PT. Geo Sriwijaya NusantaraHazred Umar FathanNo ratings yet

- 13 SK Kader Pendamping PGSDocument61 pages13 SK Kader Pendamping PGSrachman ramadhanaNo ratings yet

- Tools of Persuasion StudentsDocument4 pagesTools of Persuasion StudentsBelén Revilla GonzálesNo ratings yet

- 3.1 MuazuDocument8 pages3.1 MuazuMon CastrNo ratings yet

- Data Sheet: Item N°: Curve Tolerance According To ISO 9906Document3 pagesData Sheet: Item N°: Curve Tolerance According To ISO 9906Aan AndianaNo ratings yet

- Business Statistics: Fourth Canadian EditionDocument41 pagesBusiness Statistics: Fourth Canadian EditionTaron AhsanNo ratings yet

- Excel Crash Course PDFDocument2 pagesExcel Crash Course PDFmanoj_yadav735No ratings yet

- Risk Assessment For Harmonic Measurement Study ProcedureDocument13 pagesRisk Assessment For Harmonic Measurement Study ProcedureAnandu AshokanNo ratings yet

- Catálogo StaubliDocument8 pagesCatálogo StaubliJackson BravosNo ratings yet

- Jarir IT Flyer Qatar1Document4 pagesJarir IT Flyer Qatar1sebincherianNo ratings yet

- An Overview and Framework For PD Backtesting and BenchmarkingDocument16 pagesAn Overview and Framework For PD Backtesting and BenchmarkingCISSE SerigneNo ratings yet

- Watershed Conservation of Benguet VisDocument2 pagesWatershed Conservation of Benguet VisInnah Agito-RamosNo ratings yet

- AE HM6L-72 Series 430W-450W: Half Large CellDocument2 pagesAE HM6L-72 Series 430W-450W: Half Large CellTaso GegiaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Debate Rubric Criteria 5 Points 4 Points 3 Points 2 Points 1 Point Total PointsDocument1 pageClassroom Debate Rubric Criteria 5 Points 4 Points 3 Points 2 Points 1 Point Total PointsKael PenalesNo ratings yet

- 09-11-2016 University Exam PaperDocument34 pages09-11-2016 University Exam PaperSirisha AsadiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Axial and Torsional ElementsDocument57 pagesChapter 2 Axial and Torsional ElementsAhmad FaidhiNo ratings yet

- Answer:: Exercise-IDocument15 pagesAnswer:: Exercise-IAishika NagNo ratings yet

- Information Brochure: (Special Rounds)Document35 pagesInformation Brochure: (Special Rounds)Praveen KumarNo ratings yet

- Tensile Strength of Ferro Cement With Respect To Specific SurfaceDocument3 pagesTensile Strength of Ferro Cement With Respect To Specific SurfaceheminNo ratings yet

- In Search of Begum Akhtar PDFDocument42 pagesIn Search of Begum Akhtar PDFsreyas1273No ratings yet

- IFN 554 Week 3 Tutorial v.1Document19 pagesIFN 554 Week 3 Tutorial v.1kitkataus0711No ratings yet

- Help SIMARIS Project 3.1 enDocument61 pagesHelp SIMARIS Project 3.1 enVictor VignolaNo ratings yet

- U2 LO An Invitation To A Job Interview Reading - Pre-Intermediate A2 British CounciDocument6 pagesU2 LO An Invitation To A Job Interview Reading - Pre-Intermediate A2 British CounciELVIN MANUEL CONDOR CERVANTESNo ratings yet

- SKF CMSS2200 PDFDocument2 pagesSKF CMSS2200 PDFSANTIAGONo ratings yet

- Demonstration of Preprocessing On Dataset Student - Arff Aim: This Experiment Illustrates Some of The Basic Data Preprocessing Operations That Can BeDocument4 pagesDemonstration of Preprocessing On Dataset Student - Arff Aim: This Experiment Illustrates Some of The Basic Data Preprocessing Operations That Can BePavan Sankar KNo ratings yet