Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vindolanda and The Dating of Roman Footwear

Vindolanda and The Dating of Roman Footwear

Uploaded by

elea2005Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vindolanda and The Dating of Roman Footwear

Vindolanda and The Dating of Roman Footwear

Uploaded by

elea2005Copyright:

Available Formats

Vindolanda and the Dating of Roman Footwear

Author(s): Carol van Driel-Murray

Source: Britannia, Vol. 32 (2001), pp. 185-197

Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/526955 .

Accessed: 28/07/2013 06:51

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Britannia.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vindolanda and the Dating of Roman

Footwear

By CAROL VAN DRIEL-MURRAY

t is not widely appreciatedthat the Romanpresencein North-WestEuroperadicallytrans-

formed a number of basic technological processes, marking a fundamental break in native

traditions at a mundane level which must have profoundly affected people's everyday exper-

ience.' Archaeologically, amongst the more eye-catching innovations are the changes in the

methods of skin processing and the manufactureof footwear. It is becoming increasingly evident

that, prior to the Roman conquest, the native peoples of North-West Europe were unfamiliar with

the techniques of vegetable tanning.2 Skins were treated with oils and fats or by methods such as

smoking, and they continued to be processed in these ways in regions beyond the Roman frontiers.

Since none of these curing methods results in permanent and water-resistant leather,3 artefacts

made of animal skin will only survive under exceptional environmental conditions, such as

extreme dryness (e.g. in Egypt), salinity (e.g. in the salt mines of Hallstatt), or in peat bogs, where

a sort of secondary, natural tanning process has taken place.4 In contrast, true tanning using

vegetable extracts gives a chemically stable product, resistant to bacterial decay, which survives

well in damp, anaerobic conditions. The Classical world appears to have been conversant with

vegetable tanning from about the fourth century B.C.,5but where this knowledge originated and

how it spread is as yet unclear. As a direct result of this technological innovation, leather goods

first become fully visible in the archaeological record of North-West Europe from the start of the

Roman occupation. Shoemaking is equally affected by Roman practices, with the appearanceof a

variety of distinctive footwear styles which are technologically and stylistically unrelated to

earlier, native types. The most obvious introductions are hobnailed shoes and sandals, but even the

single-piece shoes (carbatinae) which are technologically similar to pre-Roman native footwear

are totally different in concept (FIG. 1, No. 10).6 The emergence of leatherwork as a major

component of waterlogged archaeological assemblages thus reflects the introduction of a techno-

logical package encompassing both the raw material and the products made from it. Here, there is

no question of continuity of old traditions expressed in a new medium: it is radical change which,

particularlyin the first generation following the conquest, undoubtedly carried both political and

cultural connotations.

In contrast to prehistoric and, indeed, medieval footwear, Roman shoemakers employed a

number of distinct technologies to manufacture a variety of shoe styles, some, apparently, with

quite specific functions. Thus the crew of a grain-ship sunk in the Rhine around A.D. 210 each had

at least one pair of closed shoes and one pair of sandals.7 This awareness of appropriate use

1 Such as leatherworking,basketry,woodworking andpottery:van Driel-Murray2000; Earwood 1993, 181, 193-5, 235;

Goodburn 1991; van Rijn 1993, 152; Wendrich 2000, 261.

2 Groenman-vanWaateringe et al. 1999; van

Driel-Murray2000, 302-6; van Driel-Murrayforthcoming.

3 Calnan and Haines 1991, 11.

4 Painter 1995.

5 van Driel-Murray2000.

6 Compare Hald 1972 and, for example, Rhodes 1980, figs 68-70; Goldman 1994,

116; van Driel-Murray 1987, 34.

7 van Driel-Murray 1998c, 493-8.

0 Worldcopyright:TheSocietyfor the Promotionof RomanStudies2001

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

186 CAROL VAN DRIEL-MURRAY

requires a change in attitude to clothing, and is not simply the adoption of something novel to fulfil

old functions. The adoption of Roman footwear represents an entirely new way of using clothing in

social communication, drawing on concept and symbolism which were widely understood at all

levels of society.

The introduction of vegetable tanning and Roman shoemaking technology is linked to the army

and its supply requirements:both first appearin the earliest military establishments in Europe and

indeed Egypt,8 and military settlements continue to be a prolific source of leatherwork throughout

the period, closely followed by the urban centres. In general, the riverside refuse deposits, ditch-

and well-fills which provide good conditions for the preservation of leather artefacts are impre-

cisely dated, obscuring change and development, particularly within the organic find categories

which still lack intrinsic dating methods. In certain military sites however, periodic site levelling

and restructuring,coupled with either subsidence or the need to raise the floor level, have con-

tributed to the preservation of leatherwork in excellent condition in a more closely dated strati-

graphic sequence. At Valkenburg (Netherlands) restructuringsealed in situ material dating to the

first phase (A.D. 40-50) but, as this operation raised the occupation level, much less organic

material is preserved from subsequent phases.9 At Vindolanda, however, a combination of natural

topographical features and a whole series of major structuralchanges have resulted in the preserv-

ation of exceptional quantities of leather artefacts in a stratified, relatively well dated sequence

extending over the full period of Roman occupation of the site. 10

STRATIFIED FOOTWEAR FROM VINDOLANDA

Between 1985 and 1988, over 2,600 find numbers were allocated to leather from the excavations

between the fort wall and the foundations of the stone vicus buildings." The leather was conserved

in the Chesterholm site laboratoryunder direction of Mrs P. Birley, using a method developed by

the late Mr J. Jackman (Northampton).12Over a period of several years, batches of leather were

sent to the Institute of Pre- and Protohistory, University of Amsterdam, for cataloguing and re-

search.13Of the 1,447 recognisable items of footwear, the majority is formed by shoe soles but

with an unusually high proportion of upper leather surviving, probably because cow-hide was the

favoured material. On the basis of the technology used in manufacture,the footwear can be divided

into six main categories: single piece (carbatinae), nailed shoes, sewn shoes, sandals, slippers, and

wooden clogs (Table 1).14In most cases, the surviving uppers belong to nailed soles, though sewn

constructions were also used.

The appearance of the original shoe is determined by the upper and the uppers can be grouped

into distinct styles on visual criteria, primarily the method of fastening, but also taking account of

the cutting pattern and features such as the height of shoe (below or above the ankle). Thirteen

individual styles can be distinguished, each with four or more occurrences in the assemblage as a

whole.15 From the late second century, there is, in addition, a considerable increase in styles

8 Sites such as Alesia (52 B.C.) and Qasr Ibrim (c. 23 B.C.), the leather from which is under study; Mainz (Augustan),

G6pfrich 1986, 6; Velsen (Tiberian), van Driel-Murray 1999b.

9 Groenman-vanWaateringe 1967, fig. 75a.

10 Birley 1994, 12-14; van Driel-Murray 1993.

11 Birley 1994; Bidwell 1999, 130-6. In content, inventory numbersrange from a single off-cut to substantialportions of

tents, but shoes were generally accessed as individuals, with associated pieces kept together.

12 Jackman 1990.

13 Since July 2000, Amsterdam Archaeological Centre.

14 Busch 1965, 166; van Driel-Murray 1999a, 14-18.

15 Four of the least common are omitted from FIG.2.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VINDOLANDA AND THE DATING OF ROMAN FOOTWEAR 187

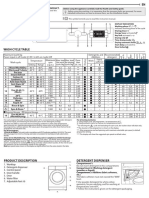

TABLE1. VINDOLANDA,

FOOTWEAR BY PERIOD(INVENTORY

CATEGORIES NUMBERS1-2599)

Period I HI I IV V VI ViI/VII

approx.date 85 90 100 105 IIb/c IIB III-IV

nailed 8 89 126 97 64 278 264

sewn 3 8 2 2 17 19

upper 2 37 48 38 18 76 44

sandal 8 6 5 4 17 43

carbatina 6 21 13 8 15 29

clog leathers 1 3 10 4

slipper 2 6 10

redeposited 2 3 much 3 2

occurring only once or twice (such as FIG.1, Nos 21, 26, 27), and though these are of importance in

comparative studies - since almost all can be paralleled elsewhere in Britain and the Continent -

they will not feature in this present discussion. A selection of popular Roman shoe styles, taken

from a variety of sites in North-West Europe, is shown on FIG.1, arrangedroughly from the early

first century A.D. (top left), to the mid-fourth century (bottom right), with cork slippers and

wooden clogs in the inset top right.

SERIATION OF FOOTWEAR (FIG. 2)

Seriated by period, on the information on dating and location provided at the time by the excav-

ator, R. Birley,16 the different shoe styles can be seen to cluster within remarkablywell defined

chronological limits. At first, with relatively few uppers involved, this effect was considered to be

coincidental, but, as the material accumulated, the clustering became more pronounced, with the

classic 'battleship' curves of frequency seriations.17FIG.2 is composed on the basis of the most

frequent styles from Vindolanda to give an outline of dated Roman footwear. Each style begins in

a small way, increases in popularity till a maximum is reached, and then declines, sometimes

slowly, but more often quite rapidly, so that the life-span of a particular shoe style falls within

clearly demarcated limits. Such close clustering confirms the essential accuracy of the dating

supplied and enables obvious outliers to be identified as re-deposited material. The two later

ditches (the so-called Antonine Ditch, Period VI, and the Inner Ditch, Period VII/VIII), which cut

a great swathe through the buildings of Period IV and V, even cutting into Period III, are an ob-

vious source of disturbance and virtually all re-deposited fragments can be attributedto the effects

of cutting and cleaning these ditches. Small fragments of Styles 5 and 7, for instance, were incorp-

orated in the muddy and indistinct zone at the bottom of the ditches, while recutting has occasion-

ally introduced fragments of later footwear into the earlier levels (e.g. two fragments of Style 23 in

Period IV).

The first three periods are the most securely dated, starting in the mid-80s (Period I, Period II c.

90, Period III c. 100), with dendro-dates indicating the beginning of the construction of the Period

IV barrack-block in autumn/winter A.D. 105.18This period may have lasted till 115 or even 120,

when the buildings were replaced by the structures of Period V, the least well-defined of the five

16 Now presented in

Birley 1994.

17 Dethlefsen and Deetz 1966.

18 Bidwell 1999, 131.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188 CAROL VAN DRIEL-MURRAY

............. ............

• .• ..'.............

. • . .

.,..,... .....-.

.....o "-...

•r.•.•. 6%

4se

al

. 'A, V 1?

..

/4'

.. ............

............. r

'iTc

2117

~?:";

?

'r~~i L"

g3"•• i •

:,•-gI~L.*

. E? a :,....... ,- ,. ...,- ,. ,.

...-<:, ....

,

•

,,,

";

......"', .?

.:,1•".~<tL .' . ..,

?

, ,: .• ,: ,0

... .oO....

") .

q- " .-:

. .

"'

\" .. .. . • '"t".r•b*l ,,s ...

o~.. . /

23,r

( r

•, (t_ •._

ss~l~;1B/ 9 o :

9

a

~r?

27

Nik

4N2A>28

FIG. 1. Selected footwear styles arrangedfrom early first century A.D. (top left) to mid-fourth century (bottom

right). Numbers correspondto FIG.2 and the text.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vindolarnda Bar Hil Numberof type at Welzheim

AN

--w-" -..-

FIG. 2. Seriation diagram of nailed footwear from Vindolanda by period, with characteristic styles from Bar Hill inserted and the number

from Welzheim superimposed for comparison. Numbers correspond to FIG.1.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

190 CAROL VAN DRIEL-MURRAY

stratified levels since it is heavily disturbed and shows a higher proportion of redeposited and

residual material. Furthermore,the structures seem to have lain open for some time and this is

reflected in the poorer preservation of the leather from this period.19

Styles 7 and 9 are present at Newstead, with one example definitely from an early pit.20But there

are none from Antonine Wall sites, nor from Hardknott, suggesting that these early styles had

already gone out of fashion by the mid-Hadrianicperiod. The styles seem to have developed in the

80s, since none are present amongst the small, though precisely dated assemblage from Castleford

(pre-A.D.86).21With the presence of the classic military boot (caliga, FIG.1, No. 4), Castleford lies

firmly in the first-century military tradition, better illustrated by sites such as Valkenburg and

Vindonissa.22No caligae have, however, been recovered at either Vindolanda or Carlisle, and this

type of footwear was evidently going out of commission during the 80s. Climate alone was not a

factor in the decline of the caliga for one of its successors was a boot with even finer and more

decorative openwork (FIG.1, No. 9). Remarkably,both the original iron hobnails and the thick cow-

hide sole layers of many of these boots had worn entirely through, while the supposedly fragile

strapworkremained intact - an indication of the skill of the shoemaker in distributing the stresses

in the upper so that no one point was over-burdened.

Despite the diminished quality of evidence from Period V, the hiatus in deposition at Vindo-

landa prior to the late second-century fill of the Period VI ditch is marked,with few footwear styles

surviving from the earlier to the later part of the second century. Fitting into this gap in the Vindo-

landa sequence is the remarkablyhomogeneous association of three main styles of footwear which

dominate the Antonine Wall complexes (FIG.1, Nos 12-13; FIG.2, line centred on A.D. 160, AW =

Antonine Wall).23 Except for two examples (both from the Period VI ditch), these are lacking at

Vindolanda, indicative of a much reduced occupation at the site throughout the period between

A.D. 140 and the mid-160s. Several of these shoes are, however, present in the earlierditches at Bird-

oswald, as well as at Carlisle, suggesting thatnot all garrisonsalong Hadrian'sWall were rundown.24

Large-scale activity resumes with the construction of a new fort (Period VI), the surrounding

ditches of which filled with rubbish during the period between about A.D. 170 and the final years of

the century. There is some evidence for progressive dumping, with earlier material in the southern

section of the ditch, while other sectors may have been levelled up at an even later date (see below,

'Sandals', p. 92). Separation of the fill into upper, middle, and bottom would have been useful

here. As in the earlier part of the century, there are three main styles, but these now differ con-

siderably in form and method of fastening. The three most popular styles are again relatively short-

lived (FIG.2, Nos 15-17), reaching their peak just after A.D. 200. On the evidence of a small frag-

ment from Bar Hill,25 No. 15 with its characteristic decoration and cross-lacing must begin in the

later second century, rapidly gaining a peak of popularity around200 and then going out of fashion

quite abruptly. Both Nos 16 and 17 appear rather later and continue for longer into the third

century. At the same time, the boot which is to dominate the later period, No. 23, is just beginning

to come into fashion.

The so-called Inner Ditch (Period VII/VIII) is associated with the Second Stone Fort, and Birley

suggests it was cut c. A.D.212,26 remaining open till the abandonmentof the site. Material seems to

19 Birley 1994, 124.

20 Curle 1911, pl. XX no. 6 and research in progress.

21 van Driel-Murray 1998b, 285-334.

22 Groenman-vanWaateringe 1967; Gansser-Burckhardt1942.

23 Robertson et al. 1975, 68-75, types A, B, C; cf. also Charlesworthand Thornton 1973; Curle 1911, pl. XX; MacIvor et

al. 1978/80, figs 16-17.

24 Padley and Winterbottom 1991, fig. 209, no. 895; Mould 1997, fig. 238.5, fig. 239.8.

25 Robertson et al. 1975, fig. 24, nos 47-8.

26 Birley 1994, 136.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VINDOLANDA AND THE DATING OF ROMAN FOOTWEAR 191

have been dumped here throughout the third and fourth centuries, but re-cutting has disturbed the

fill, and furtherdifferentiation is impossible. The quality of the contexts is not, therefore, entirely

consistent throughout the site's occupation: the first four periods span less than forty years,

allowing the construction of a detailed picture of changing footwear fashions. The hiatus in

mid-century can be filled with material from the historically defined Antonine Wall sites, with the

Period VI ditch at Vindolanda forming the end of this continuous sequence. For the purposes of the

seriation, the material is centred on A.D. 200 (dotted line), though deposition obviously extended

over a longer period, perhaps twenty to thirty years. Centring Periods VII/VIII(InnerDitch) at A.D.

230 is entirely arbitrary, though the presence of Styles 16 and 17 together with certain other

indicators (some of the rare shoe styles and the sandals, see below) does suggest that dumping

began quite soon after its construction, even if most material was regularly cleared out. For less

chronologically sensitive research Vindolanda thus provides three distinct phases for internal

comparison and for the investigation of long-term trends: Early (Periods I-IV, c. 90-120), Middle

(VI = c. 200), and Late (VII/VIII, third to fourth century).

APPLICATIONS

One of the most remarkablefeatures of Roman nailed footwear is its international character. Not

only do styles change rapidly, but the process of change is contemporaneous throughoutthe North-

West provinces, and indeed, where appropriateevidence survives, in the Mediterraneanprovinces

as well.27 In this context, it may not be entirely incongruous to utilise the concept of 'fashion' to

describe the rapid succession of new styles. One consequence of this international dimension is

that the framework established by means of the dated sequence from Vindolanda can be applied to

other situations.

At a simple level, footwear can be utilised as a dating tool in its own right. Thus an undated

group of shoes from Old Penrith28can be identified as Style 17, with its characteristic horizontal

lacing leaving an upstanding comb along the length of the foot. Reference to the Vindolanda

seriation diagram suggests a date in the late second/early third century for this group and, hence,

the associated finds. Similarly, the two periods of occupation at Newstead are evident in the foot-

wear spectrum, with a group of late first-/early second-century styles comparable to Vindolanda

Periods II-III and a later group consistent with Antonine Wall assemblages.29 At Welzheim

(Baden-Wiirttemberg,Germany), a timber well with a dendrochronological construction date of

A.D. 190+10 was backfilled a couple of decades later in a single operation with rubbish which

included about 100 shoes of different types.30 When numbers are set against the Vindolanda

sequence (FIG.2, lines centred on c. 210) both similarities and differences become apparent.As at

Vindolanda, cork slippers form about 5 per cent of the assemblage (FIG.1, No. 2), and the most

popular styles are Nos 15 and 16, the latter at Welzheim also being copied as single-piece

carbatinae.31The fact that the boot No. 23 is represented by only five small cut-up fragments may

indicate that it was only just coming into fashion, but the absence of the shoe No. 17, together with

the high percentage of carbatinae (Welzheim 26 per cent, Vindolanda Period VI 5 per cent) may

highlight shifts of emphasis and consumer choices as yet unsuspected and only revealed when

entire assemblages can be compared in this manner.

The Vindolanda sequence can also be used to establish dating ranges in poorly defined riverside

27 van Driel-Murray 1987.

28 Thornton 1991, 220, fig. 114.

29 Curle 1911,

pl. XX nos 2, 4 and 6 (early), nos 5 and 7 (Antonine); also unpublished research in progress.

30 van

Driel-Murray 1999a, 11-12.

31 Not included in FIG.2 and raising the total number from ten to fifteen.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

192 CAROLVAN DRIEL-MURRAY

dumps containing material of mixed origin in complex stratigraphies which have not been

recognised in excavation. The well-published, but largely undated, footwear from the vicus at

Valkenburg (Netherlands) may serve as an example. Beginning with a small number of mid-

second-century styles (Style 11), the majority of the identifiable shoes cluster around the later

second-/earlier third-century transition (Styles 15, 17), with just a few obviously rather later.32

Some of the sandals may even extend to the mid-third century. This pattern is repeated in the

unpublished assemblage of footwear from the fort at Vechten (Netherlands), and in both cases

suggests that occupation in the vici aroundthese forts continued well into the third century.

SANDALS (FIG. 3)

Sandals are the most obviously Mediterranean contribution to the footwear fashions of the

northernprovinces. Although the sole layers are thonged together, sandals are also usually hob-

nailed, leaving little doubt but that they were used outdoors. In general, sandals are rare on early

military sites and those from Vindolanda Periods I-IV occur mainly in smaller sizes, where they

are obviously related to the presence of families.33 Sandals form a much higher proportion of the

footwear in the early civilian settlements (23 per cent at Billingsgate, London34), although still

predominantlyin smaller sizes.

Unlike the radical changes in the appearanceof closed shoes, sandals undergo a continuous and

logical development in form throughout a period of 400 years, and once more this development is

regardless of provincial boundaries (FIG.3).

Up to Vindolanda Period V sandals possess a naturalshape often with two to three indents mark-

ing the toes. These are occasionally oddly arrangedto emphasise the second toe,35 clearly a res-

ponse to the Classical admiration of the elongated second toe which is so noticeable in sculpture

from the Hellenistic period onwards.36Classical ideals concerning the body appear, therefore, to

be accompanying the introduction and use of sandals in the northernprovinces: here it is signific-

ant to note that on the basis of shoe sizes37it is specifically women who arethe first to take up the full

range of Roman footwear styles in civilian settlements such as London and K61n.38At Vindolanda,

however, two of the sandals from the Period IV barrack-blockare adult male in size: one is decor-

ated with a rather official-looking stamp, depicting an eagle, which also occurs on an identical

sandal from London,39making it likely that there was a status as well as a gender component in the

take-up of the new fashions. Decorative stamping is common on sandal soles at this period, with

urns, concentric circles, and florets being general favourites, but occasionally more elaborate

designs appearwhich seem to have been impressed with metal dies.40The sandal soles from Period

V at Vindolanda reveal the transitional nature of the deposit, with a few of the earlier types and a

more numerous group resembling the more developed shapes of the Period IV ditch which are

probably to be associated with activities immediately preceding its construction.

32 Hoevenberg 1993, fig. 33, fig. 54 no. 656 (early); figs 26, 35 (mid); fig. 23 no. 596 and fig. 56 no. 588B (late).

33 van Driel-Murray 1998a, 348-50.

34 Rhodes 1980, 120.

35 This also appearsin London, e.g. Rhodes 1980, fig. 66 no. 628.

36 Exemplified in the colossal marble foot in the Devonshire collection at ChatsworthHouse (Morrow 1985, pl. 74) and

also Roman sculpture, cf. Goldman 1994, figs 6.5, 6.9, 6.10, for feet with indented sandals.

37 van Driel-Murray 1998a, 344, fig. 1.

38 Sandals, slippers, closed shoes, carbatinae, cf. Rhodes 1980 and Schleiermacher 1982.

39 van Driel-Murray 1993, fig. 27.5 and London MOL archive, unpublished.

40 van Driel-Murray 1993, fig. 27.5 and fig. 28; van Driel-Murray 1977; again, an international phenomenon

(Schleiermacher 1982, figs 17-19; Hoevenberg 1993, 226-7; and from Egypt, Montembault 2000, 113). All-over stamping

again becomes common in Egypt from the later third century onwards.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VINDOLANDA AND THE DATING OF ROMAN FOOTWEAR 193

period date VINDOLANDA DATA

COMPARATIVE

AD

17

14

Vill

1 250

IV

n2

fit 10

3. The changing shape of sandal soles: Vindolanda by period with dated comparisons: 1-7. Vindolanda; 8.

FIG.

London Id/IIa (in prep.); 9. Woerden (van Driel-Murray 1998c); 10-11. Welzheim (van Driel-Murray 1999a); 12.

Zugmantel Well 274, post A.D. 210 (Busch 1965); 13-15. Saalburg Well 14 (Busch 1965); 16. London Dowgate

IIId/IVa(in prep.); 17. London (MacConnoran1986); 18. Birdoswald (Mould 1987).

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

194 CAROL VAN DRIEL-MURRAY

Sandals only become common at Vindolanda in the Period VI ditch (Table 1), where the ex-

tended period of dumping is evident in the range of forms; again, separationof the fill into approx-

imate levels would have been useful. In common with other late second-/ early third-century

assemblages,41 there are two parallel trends in sandal shapes: on the one hand narrow, sinuous

shapes and on the other an increasing widening of the front. To judge from the size distribution this

appears to reflect separate male and female fashions, although the occurrence of small-sized wide

sandals with cusped edges hints at a more complex relationship, where it may be the presence or

absence of toe indents which distinguishes masculine and feminine styles. If this surmise is

correct, it would provide one of the few instances where it is possible to distinguish the sex of

children in material culture. Wide sandals, without toe indents, in small sizes, would in this case

point to a well-developed masculine identity in clothing by at least the age of four or five.42 This

trend is remarkable,for, on the whole, Roman shoe styles were worn by men, women, and children

indiscriminately. An interesting case is Style 15, which is depicted on tombstones from Trier as

being worn by a schoolmaster and his boy pupils,43was worn (with socks) by a fully clothed young

woman buried at Les Martres-de-Veyre (France),44and was made in a range of sizes at Vindo-

landa, Welzheim, and numerous other sites. A variant of the closed boot used by the soldiers at

Vindolanda (Style 5) was also being worn by the female occupants of the pre-Hadrianicpraetor-

ium. Gender differentiation in footwear does not appear to be an issue until the later second

century, and even then the most popular styles in closed footwear (Styles 23, 27) are used by men,

women, and children alike.

The process through which women's sandals evolved from the natural shapes of the first and

earlier second century to the narrow, sinuous form current later is unclear, as sandals are

conspicuously absent from the Antonine Wall complexes. There are just three examples, all from

Bar Hill: two soles with indents and one sinuous shape, perhaps indicating that this form was

emerging in the 160s.45Judging from the position of the toe strap, the single indent still reflects the

ideal of the projecting second toe, since it bears little relation to the actual position of the toes.

These rather exaggerated forms are not confined to urban centres: women in isolated and rather

poor frontier settlements such as Welzhiem, in the civilian vici such as Pommeroeul in Gallia

Belgica, and even rural settlements in the Rhine delta area also sported these fashionable, elegant

sandals.

Men's sandals develop in the opposite direction: the toe indents disappearand the front becomes

increasingly broad and blunt. Nailing is frequently arrangedin decorative patterns and the thonged

construction is invisible from the outside until wear exposes the thong slits.46 The toe straps are

sometimes decorated with tiny metal studs (FIG.1, No. 22). There is some degree of overlap in the

sandal forms from the two Vindolanda ditches, suggesting that dumping in the Period VI ditch

continued well into the third century, while that in the Period VII/VIIIditch must have begun quite

soon after its construction. Third-centuryassemblages elsewhere (London, Mainz, the Saalburg)

reveal a continuing process of widening, often accompanied by an indent at the base of the big toe

and, increasingly, a depression at the centre front, which shows a marked tendency to flatten out,

leaving the sole almost triangularin shape. The more exaggerated shapes of the second half of the

third century, which appearto continue into the early fourth century, are absent from Vindolanda,

supporting Birley' s view that the vicus was largely abandoned by the end of the century, although

41 van Driel-Murray 1999a, Abb. 41.

42 Not only at Vindolanda, but also at Valkenburg (Hoevenburg 1993, fig. 57), and London (MacConnoran 1986, figs

8.16, 8.18, 8.24). Correlation of children's foot sizes and ages, cf. van Driel-Murray 1999a, 35, Abb. 12.

43 Esp6randieu 1922, no. 5149; van Driel-Murray 1999a, 72, Abb. 52.

44 van Driel-Murray 1999c.

45 Robertson et al. 1975, fig. 21 no. 2; from Egypt, see Montembault 2000, 107.

46 Gbpfrich 1986, Abb. 25.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VINDOLANDAAND THEDATINGOFROMANFOOTWEAR 195

this may also be due to natural processes, since the upper levels of the ditch fill appear to have

suffered from periodic drying out. Late sandals are well represented at Birdoswald,47at many other

sites in Britain, and on the Continent; in Egypt the shape is even imitated in sandals made of

vegetable fibre.48Such very wide soles will have affected the carriage of the wearer - and hence

the drape of the clothing - to a marked degree, as they impose a struttinggait with the shoulders

thrown back. This effect has previously been associated with the militarisation of society in

general.49At the same time, more restrained,possibly - judging from the sizes - female, sandals

with a deep, scroll-like side indent occur in late third-/early fourth-century assemblages from

London and Gaul.50The impression gained from the sandals is that the bulk of the leather from the

late ditch at Vindolanda belongs to the mid-third century, though fourth-century footwear, in the

form of sewn shoes and carbatinae, is certainly also represented in some quantity.

DISCUSSION

Due to its high turnover,footwear is particularlyresponsive to changing consumer demand and the

seriation of styles from Vindolanda provides a framework for the evaluation of these preferences

in their social and historical context. Successful fashions achieve a dominant position within a

decade or so of their first appearance,implying rapid acceptance by a large sector of the provincial

population. It is noticeable that change is not only rapid, but also radical, for only rarely do popular

styles evolve from earlier fashions, and the suspicion that a conscious search for novelty lies

behind these changes is unavoidable. In a very real sense earlier styles would be seen as old-

fashioned and inappropriate (compare Style 6 with 12, for instance); consequently, the term

'fashion' may not be entirely incongruous to describe these changes. At any one time consumers

expressed a preference for just a small selection of the many styles available. Thus, at Welzheim

80 per cent of the total is formed by just three styles, with five completely different styles

represented in the remaining 20 per cent. In the contemporaryphase at Vindolanda 73 per cent of

the footwear belongs to four styles, with eight exceedingly diverse styles making up the rest. Given

the range available, footwear always allowed individuals ample opportunity for choice, but

nevertheless taste gravitated towards common notions concerning appropriatedress ratherthan to

regional, gender, or professional differentiation. That something as mundane as footwear responds

to conscious choice exercised by individuals aspiring to participate in an international and

recognisable Roman identity by means of fashions in clothing must seriously call into question the

recent tendency to regardthe Roman occupation - in the North-West provinces in particular- as

a thin veneer which left the majority of the population unaffected.

CONCLUSION

Leaving aside the nailed soles and all material from Period V, on account of the problems of

disturbance (Table 1), less than 4 per cent of the total of 488 pieces of footwear from Vindolanda is

recognisably re-deposited. Despite doubts expressed concerning the validity of dating, the

seriation of the footwear and the remarkablytight, logical patterns obtained confirm the potential

47 Mould 1997, fig. 240.

48 Some examples: London (MacConnoran 1986, 222-3 and

unpublished material in the Museum of London Archive);

Mainz (GOpfrich1986, nos 33, 48; Mould 1990, fig. 143); Univeristy College London, Petrie Museum, from Hawara (UC

28309); and unpublished material from France and Belgium.

49 van Driel-Murray 1987, 35.

50 Unpublished material.

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

196 CAROL VAN DRIEL-MURRAY

of the site for in-depth studies on long-term developments in material culture and environment.

Though the detail of the first four periods cannot be matched, the quantity of material from the two

later ditches forms important control groups, particularly as the Period VI ditch can be regarded as

centring on A.D. 200 ? 20. The organic material in the fill of the Period VII/VIII ditch appears to

date predominantly from the mid-third century, but with a substantial component of later footwear,

which suggests that dumping went on for much longer and other, more resistant material categor-

ies would show a much longer sequence. As far as the leather is concerned, the sheer size of the

Vindolanda assemblages smoothes out the effects of irregularities and disturbances, highlighting

the general trends over a long period of time. With the possibilities for independent cross-checking

by means of other dated assemblages, and the rapid changes in fashion, footwear is particularly

well suited for seriation, with the result that research on other less easily dated categories can be

structured within this general framework.

Amsterdam Archaeological Centre, University of Amsterdam

c.v.driel @frw.uva.nl

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bidwell, P. (ed.) 1999: Hadrian's Wall 1989-1999, Newcastle upon Tyne

Birley, R. 1994: The Early Wooden Forts. Vindolanda Research Reports, vol. I, Hexham

Busch, A.L. 1965: 'Die rbimerzeitlichen Schuh- und Lederfunde der Kastelle Saalburg, Zugmantel und

Kleiner Feldberg', Saalburg-Jahrbuch 22, 158-210

Calnan, C., and Haines, B. 1991: Leather: its Composition and Changes with Time, Northampton

Charlesworth, D., and Thornton, J.H. 1973: 'Leather found in Mediobogdum, the Roman fort of

Hardknott', Britannia 4, 141-52

Curle, J. 1911: A Roman Frontier Post and its People. The Fort of Newstead in the Parish of Melrose,

Glasgow

Dethlefsen, E., and Deetz, J. 1966: 'Death's heads, cherubs, and willow trees: experimental archaeology in

colonial cemeteries', American Antiquity 31, 502-10

Driel-Murray, C. van 1977: 'Stamped leatherwork from Zwammerdam', in B.L. van Beek (ed.), Ex Horreo,

Amsterdam, 151-64

Driel-Murray, C. van 1987: 'Roman footwear: a mirror of fashion and society', in D.E. Friendship-Taylor,

J.M. Swann and S. Thomas (eds), Recent Research in Archaeological Footwear, Association of

Archaeological Illustrators and Surveyors Technical Paper 8, 32-42

Driel-Murray, C. van 1993: 'Preliminary report on the leather', Vindolanda Research Reports, vol. III,

Hexham, 1-75

Driel-Murray, C. van 1998a: 'A question of gender in a military context', Helinium 34, 342-62

Driel-Murray, C. van 1998b: 'The leatherwork from the fort', in H.E.M. Cool and C. Philo (eds), Roman

Castleford Vol. I. The Small Finds, Yorkshire Archaeology 4, Wakefield, 285-334

Driel-Murray, C. van 1998c: 'Die Schuhe aus Schiff I und ein lederner Schildiiberzug', in J.K. Haalebos,

'Ein r6misches Getreideschiff in Woerden', Jahrbuch des R5misch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums

Mainz 43, 493-8

Driel-Murray, C. van 1999a: Das Ostkastell von Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis: die r6mischen Lederfunde,

Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor-und Fruihgeschichtein Baden-Wtirttemberg47, Stuttgart

Driel-Murray, C. van 1999b: 'Dead men's shoes', in W. Schluiterand R. Wiegels (eds), Rom, Germanien

und die Ausgrabungen von Kalkriese, Osnabriick, 169-89

Driel-Murray, C. van 1999c: 'A set of Roman clothing from Les Martres-de-Veyre, France',

Archaeological Textiles Newsletter 28, 11-15

Driel-Murray, C. van 2000: 'Leatherwork and skin products', in P.T. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds), Ancient

Egyptian Materials and Technology, Cambridge, 299-319

Driel-Murray, C. van forthcoming: 'Practical evaluation of a field test for the identification of ancient

vegetable tanned leathers', Journal of Archaeological Science

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VINDOLANDAAND THEDATINGOFROMANFOOTWEAR 197

Earwood, C. 1993: Domestic WoodenArtefacts in Britain and Irelandfrom Neolithic to Viking Times, Exeter

Esperandieu, E. 1922: Recueil general des bas-reliefs, statues et bustes de la Gaule, Paris

Gansser-Burckhardt,A. 1942: Das Leder und seine Verarbeitung im romischen Legionslager Vindonissa,

Basle

Goldman, N. 1994: 'Roman footwear', in J.L. Sebesta and L. Bonfante (eds), The World of Roman

Costume, Wisconsin, 101-29

Goodburn, D. 1991: 'A Roman timber framed building tradition', Archaeological Journ. 148, 182-204

Gdpfrich, J. 1986: 'R6mische Lederfunde aus Mainz', Saalburg Jahrbuch 42, 5-65

Groenman-van Waateringe, W. 1967: Romeins lederwerk uit ValkenburgZ.H., Groningen

Groenman-van Waateringe, W., Kilian, M., and London, H. van 1999: 'The curing of hides and skins in

European prehistory', Antiquity 73, 884-90

Hald, M. 1972: Primitive Shoes, Copenhagen

Hoevenberg, J. 1993: 'Leather artefacts', in R.M. Dierendonck, D.P. Hallewas and K.E. Waugh, The

Valkenburg Excavations 1985-1988, Amersfoort, 217-340

Jackman, J. 1990: 'Conservation of Roman leather from Vindolanda', WorldLeather 1990, 62-4

MacConnoran, P. 1986: 'Footwear', in L. Millar, J. Schofield and M. Rhodes (eds), The Roman Quay at St

Magnus House, London. Excavations at New Fresh Wharf, Lower Thames Street, London 1974-78,

London & Middlesex Arch. Soc. Special Paper 8, London, 218-26

MacIvor, I., Thomas, M.C., Breeze, D. 1978/80: 'Excavations in the Antonine Wall fort of Rough Castle,

Stirlingshire 1957-61', Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scotland 110, 230-85

Montembault, V. 2000: Musde du Louvre: Catalogue des chaussures de l'antiquit egyptienne, Paris

Morrow, K.D. 1985: Greek Footwear and the Dating of Sculpture, Wisconsin

Mould, Q. 1997: 'Leather', in T. Wilmott, Birdoswald. Excavation of a Roman Fort on Hadrian's Wall and

its Successor Settlements: 1987-92, English Heritage Archaeological Reports 14, London, 326-41

Mould, Q. 1990: 'The leather objects', in S. Wrathmell and A. Nicholson (eds), Dalton Parlours. Iron Age

Settlement and Roman Villa, Yorkshire Archaeology Monograph 3, Wakefield, 231-5

Padley, T.G., and Winterbottom, S. 1991: The Wooden, Leather and Bone Objects from Castle Street,

Carlisle, Excavations 1981-2, Cumberland & Westmorland Antiq. & Arch. Soc. Res. Ser. 5, fasc. 3,

Kendal

Painter, T.J. 1995: 'Chemical and microbiological aspects of the preservation process in Sphagnum peat',

in R.C. Turnerand R.G. Scaife (eds), Bog Bodies. New Discoveries and New Perspectives, London, 88-99

Rhodes, M. 1980: 'Leather footwear', in D.M. Jones and M. Rhodes (eds), Excavations at Billingsgate

Buildings, Lower Thames Street, London, 1974, London & Middlesex Arch. Soc. Special Paper 4,

London, 99-128

Rijn, P. van 1993: 'Wooden artefacts', in R.M. Dierendonck, D.P. Hallewas and K.E. Waugh (eds), The

Valkenburg Excavations 1985-1988, Amersfoort, 146-216

Robertson, A., Scott, M., and Keppie, L. 1975: Bar Hill: a Roman Fort and its Finds, BAR 16, Oxford

Schleiermacher, M., 1982: 'R6mische Leder- und Textilfunde aus K6ln', Archiiologischer

Korrespondenzblatt 12, 205-14

Thornton, J. 1991: 'Shoe leather', in P.S. Austen, Bewcastle and Old Penrith, Cumberland & Westmorland

Antiq. & Arch. Soc. Res. Ser. 6, Kendal, 219-24

Wendrich,W. 2000: 'Basketry', in P.T. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds), Ancient Egyptian Materials and

Technology, Cambridge, 254-67

This content downloaded from 128.151.244.46 on Sun, 28 Jul 2013 06:51:47 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Ancient Egypt, Grade 4 To 6 - 3706iDocument102 pagesAncient Egypt, Grade 4 To 6 - 3706iLisa100% (13)

- The House of Correction For Wayward Girls Edited by Miss Helena FrostDocument115 pagesThe House of Correction For Wayward Girls Edited by Miss Helena FrostMarianne Martindale100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Holw NightDocument9 pagesHolw NightdenisemariaferreiraNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- TAM-Global Apparel Business Trends - OverviewDocument7 pagesTAM-Global Apparel Business Trends - OverviewMonjurul Islam NafisNo ratings yet

- Crochet Pattern Bing BongDocument9 pagesCrochet Pattern Bing BongMonserrat Alejandra Olivares Cabrera100% (1)

- Verb To Be Exercises 2Document2 pagesVerb To Be Exercises 2Oksana DerechaNo ratings yet

- TLE 7 Dressmaking Week 1Document22 pagesTLE 7 Dressmaking Week 1Judith AlmendralNo ratings yet

- Fashion Media: Past and PresentDocument6 pagesFashion Media: Past and PresentnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Industrial Laundry and Dry CleaningDocument5 pagesProject Report On Industrial Laundry and Dry CleaningEIRI Board of Consultants and PublishersNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 2022-04-28 at 10.36.07Document1 pageScreenshot 2022-04-28 at 10.36.07Vivian AnumiriNo ratings yet

- Company: Company Sporting Goods Co. LTDDocument19 pagesCompany: Company Sporting Goods Co. LTDFelipe MoreiraNo ratings yet

- TDT 151 Lecture Notes 2022Document44 pagesTDT 151 Lecture Notes 2022Ollè WorldwideNo ratings yet

- Whirlpool BIWDWG861484uk enDocument4 pagesWhirlpool BIWDWG861484uk ennadaljoachim77No ratings yet

- Print - Udyam Registration CertificateTANISHA ARORADocument2 pagesPrint - Udyam Registration CertificateTANISHA ARORAukprsharma4No ratings yet

- TXE-407 (Garments Manufacturing Technology - III) : Lecture-4 Topics-Normal Wash Recipe For Denim GarmentsDocument11 pagesTXE-407 (Garments Manufacturing Technology - III) : Lecture-4 Topics-Normal Wash Recipe For Denim GarmentsZisan AhmedNo ratings yet

- MR14 Project Report American Eagle OutfittersDocument22 pagesMR14 Project Report American Eagle Outfittersnikhilsp7No ratings yet

- Advanced Spoken: How To Extend AnswerDocument6 pagesAdvanced Spoken: How To Extend AnswerCosmo SchoolNo ratings yet

- Elomi - Lingerie Spring Summer Collection Catalog 2020 PDFDocument52 pagesElomi - Lingerie Spring Summer Collection Catalog 2020 PDFBabyfat FataldoNo ratings yet

- Monkey MoneyDocument3 pagesMonkey Moneywilberespinosa773No ratings yet

- Janome G1206 Sewing Machine Instruction ManualDocument52 pagesJanome G1206 Sewing Machine Instruction ManualiliiexpugnansNo ratings yet

- Visigoths Vs Mall Goths Character SheetsDocument10 pagesVisigoths Vs Mall Goths Character SheetsGianluca ValliNo ratings yet

- More Magic City Murders ExcerptDocument10 pagesMore Magic City Murders Excerptapi-357221863No ratings yet

- Indi Wife 1Document28 pagesIndi Wife 1mahima patelNo ratings yet

- Wanted: Wellington. 12Document12 pagesWanted: Wellington. 12Alex IgnatNo ratings yet

- Weekly GP Assg NikeDocument20 pagesWeekly GP Assg NikeCohort 20No ratings yet

- Four H Dyeing & Printing Ltd. (Yarn Dyeing Unit)Document82 pagesFour H Dyeing & Printing Ltd. (Yarn Dyeing Unit)gohoji4169No ratings yet

- I Am Not Twenty Four by Sachin GargDocument179 pagesI Am Not Twenty Four by Sachin GargShraddha JadhavNo ratings yet

- Where Is Tao.Document12 pagesWhere Is Tao.Guillermo LeónNo ratings yet

- 91 MesurmentsDocument25 pages91 MesurmentsKazi Abdullah All MamunNo ratings yet

- IELTS Vocabulary ClothesDocument2 pagesIELTS Vocabulary Clothesbalnur.beysengali.08No ratings yet