Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Reasoning in Manual Therapy

Uploaded by

Khushboo PakhraniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Reasoning in Manual Therapy

Uploaded by

Khushboo PakhraniCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/21700582

Clinical Reasoning in Manual Therapy

Article in Physical Therapy · January 1993

DOI: 10.1093/ptj/72.12.875 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

162 9,029

1 author:

Mark Jones

University of South Australia

63 PUBLICATIONS 2,684 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Textbook Clinical Reasoning in Musculoskeletal Practice View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Mark Jones on 17 February 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Clinical Reasoning in Manual Therapy

Clinical reasoning refers to the cognitive processes or thinking used in the evalua- Mark A Jones

tion and management of a patient. In this article, clinical reasoning research

and expert-novice studies are examined to provide insight into the growing un-

derstanding of clinical reasoning and the nature of expertise. Although

bypothetic~deductivemethod of reasoning are used by clinicians at all leuels of

experience, experts appear to poses a superior otganization of knowledge. Ex-

perts oflen reach a diagnosis based on pure pattern recognition of clinical pat-

terns. With a n atypical problem, however, the expert, like the novice, appears to

rely more on bypotheticedeductive clinical reasoning. Five categories of hypothe-

ses are pmposed for physical therapists wing a bypothetico-deductivemethod of

clinical reasoning. A model of the clinical reasoning proces for physical therapists

is presented to bring attention to the hypothesisgeneration, testing, and modijica-

tion that I feel should take place through all aspects of the patient encounter.

Examples of common errors in clinical reasoning are highlighted, and sugges-

tionsfor facilitating clinical reasoning in our students are made. [JonesMA.

Clinical reasoning in manual therapy. Pbys Ther 1992;72:875-884.]

Key Words: Clinical competence, Decision making, Diagnosis, Manual therapy.

There is an increasing demand for observations and the hypotheses are are increasing,'-5 research in clinical

accountability of physical therapists then tested through subsequent data reasoning within physical therapy is

from within the profession as well as collection and modified as a result of still sparse.- Considerable research,

outside, including funding agencies, the outcome of the test. Similarly, however, has been conducted in the

competing health practitioners, and physical therapists should b e taught to area of thinkingkeasoning and the

the increasingly more health con- use clinical reasoning skills in their nature of expertise in such diverse

scious consumer. This demand is met examination and management of fields as medicine, nursing, psychol-

in part by the profession's ongoing patients. But what reasoning skills ogy, artificial intelligence, program-

efforts to teach and conduct scientific should we teach? And how should ming, law, mathematics, engineering,

inquiry with the aim of improving this be balanced against the teaching and physics.S13This article will

and validating physical therapy prac- of knowledge? Understanding the briefly highlight research findings that

tice. Equally important, physical thera- cognitive components of clinical rea- provide insight into the growing un-

pists must apply the methods of scien- soning and in particular the differenti- derstanding of clinical reasoning and

tific inquiry to the examination and ating features between experts and the nature of expertise relevant to

management of patient problems. novices should enable us to critically physical therapy. Although further

Accountability sufferswhen therapists evaluate our own reasoning and de- research is needed to clarify the na-

unquestioningly follow examination sign educational activities to facilitate ture of clinical reasoning, the majority

and treatment routines without con- improved reasoning. of clinical reasoning literature sug-

sidering and exploring alternatives. gests that expert clinicians have a

Scientific reasoning often includes the Although theoretical discussions and highly developed organization of

hypothetico-deductive method, in educational suggestions on aspects of knowledge and use a hypothetico-

which hypotheses are generated from clinical reasoning in physical therapy deductive method in their clinical

reasoning.14 A model of a clinical

reasoning process for physical thera-

-

pists is presented that emphasizes a

MA Jones, PT, is Cwrdinator, Post Graduate Manipulative Physiotherapy Programmes, School of hypothesis testing approach to clinical

Physiotherapy, University of South Australia, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

5000. reasoning. Clinical reasoning that is

Physical Therapy /Volume 72, Number 12December 1992

hypothetico-deductive will assist clini- In a review of research in medical rected. This finding of the importance

cians in avoiding common errors of clinical reasoning, Feltovich and Bar- of good hypotheses highlights the

reasoning and enhance their recogni- rows15 described hypotheses and data crucial role the clinician's knowledge

tion of clinical patterns and organiza- gathering that were considered in the base has in the clinical reasoning

tion of knowledge. clinical reasoning studies. The vari- process. The importance of knowl-

ables affecting hypothesis generation edge and its organization are also

Cllnkal Reasonlng included the percentage of patient reflected in the seminal work of El-

data items or the time it took to cre- stein and colleagues,16in which clini-

Clinical reasoning can be defined as ation of the first hypothesis. The total cal reasoning performance was shown

the cognitive processes, or thinking number of hypotheses considered to vary greatly across cases. That is,

used in the evaluation and manage- and number of hypotheses actively clinical reasoning is specific to one's

ment of a patient. Other terms includ- considered at any one time were also area of work (eg, orthopedics, neurol-

ing "clinical decision making,"l "clini- studied. There was no difference in ogy, and so forth), dependent on the

cal problem solving,"8 and "clinical any of these variables across different clinician's organization of knowledge

judgrnent"l0 also appear in the litera- specialties or across different levels of in the particular area.

ture and frequently are used inter- experience within the same specialty.

changeably. Clinical decision making Although these hypothesis-related These early medical studies provide

and clinical judgment focus on the variables are common to all clinicians, an overall picture of a clinical reason- ,

diagnostic decision-making aspect of their importance to effective clinical ing process that is hypothetico-

the clinical reasoning process, reasoning was unclear, as none were deductive and universally applied by

whereas problem solving typically consistently predictive of the quality clinicians at all levels of experience.

refers to the steps involved in work- of outcome (eg, correct diagnosis and The process involves collecting and

ing toward a problem solution. Prob- management plan). analyzing information, generating

lem solving also infers the therapist's hypotheses concerning the cause or

aim is to solve the patient's problem. The data-gathering variables centered nature of the patient's condition, in-

Some patient problems, however, are on the general themes of thorough- vestigating or testing these hypotheses

"unsolvable." Our profession's aim is ness, efficiency (ie, important to non- through further data collection, and

to evaluate the patient problem, iden- important information collected), determining the optimal diagnostic

tifylng factors amenable to physical activeness (ie, extent to which data and treatment decisions based on the

therapy to effectively manage the collected are evaluated in relationship data obtained.

problem. The term "clinical reason- to hypotheses being considered to

ing" has broader connotations and is test appropriateness of hypotheses), The Nature of Expertise

used in this article to refer to the and accuracy in interpretation (ie,

cognitive processes used in achieving correctness of interpretations as sup- "Experts" in the early medical educa-

this aim of evaluating and managing porting or not to hypotheses). The tion research were typically those

the patient's problem. value of the data-gathering measures selected by peer nomination, whereas

to reveal important aspects of clinical "novices" were usually students at

Cllnlcal Reasonlng In reasoning were also questionable, as varying levels of their education.lb20

Medlclne: A Unhrersal they did not discriminate among Pate1 and Groen21 have suggested that

Process clinicians from different specialties o r expertise be considered along the

clinicians with different levels of expe- dual continuum of both generic and

A summary of findings from early rience or peer-judged proficiency. specialized knowledge. They define a

medical education research in clinical The importance of these data- novice as an individual who has the

reasoning highlights some universal gathering variables to the products of prerequisite knowledge assumed by

aspects of clinical reasoning and the the rea5oning process was also ques- the domain. A subexpert, according to

significance that the organization of tioned. With the exception of "accura- Pate1 and Groen, is an individual with

one's knowledge has to the differenti- cy in interpretation,"16 no other data- generic knowledge, but inadequate

ation of expert clinicians and novices. gathering variable correlated with specialized knowledge of the domain,

Early medical education studies ana- quality of diagnosis and management and an expert is defined as an individ-

lyzed clinicians' thoughts (eg, percep plan. ual with specialized knowledge of the

tions, interpretations, plans), either domain. These definitions provide

retrospectively as the clinicians The best indicator of the correctness sufficient distinctions for interpreting

thought aloud while being prompted of diagnosis and management plan the expert-novice literature cited in

by a video or audio playback of a was the quality (as judged by expert this article. Although I will not suggest

patient examination just completed or standards) of hypotheses consid- my own expert-novice distinction for

concurrently as the clinicians read a ered.17-20If the appropriate hypothe- physical therapy, I do feel the full

patient's unfolding clinical history. ses were not considered from the range of competencies inherent to

start, the clinician's subsequent inqui- physical therapy including knowledge,

ries would presumably be misdi- interpersonal, manual, and clinical

Physical Therapy /Volume 72, Number 12December 1992

reasoning skills should b e incorpo- radiographs.z8This superior ability to zation of knowledge. Experts make

rated into any expert-novice see meaningful patterns is not the significantly more inferences about

distinction. result of superior perceptual or mem- clinically relevant information and

ory skills; rather it reflects a more chunk information into recognizable

Expert clinicians have a superior highly organized knowledge base.2" patterns.32 Novices make more verba-

organization of knowledge and use a tim recall of the surface features of a

combination of hypothetico-deductive These representations of the problem problem and have less developed and

reasoning and pattern recognition o r will in turn influence the subsequent fewer variations of patterns stored in

forward reasoning.16J1.22 Support for search for a solution. The expert their memory. For example, a novice

the importance of one's organization chess player's conceptualization of the may recall the specific, yet superficial,

of knowledge is available from the game into strengths and vulnerabili- detail that the patient's shoulder hurt

literature of cognitive psychology.23~24 ties lessens the number of appropri- with attempted elevation in early

Experts acquire efficient ways of rep- ate moves to consider. When the activities. Further details such as the

resenting information in their work- physicist characterizes a problem as exact site of pain and position of the

ing memory. Studies of problem an example of a physics law, the law patient's neck, shoulder, and arm may

solving and expert-novice differences itself substantially directs the form not have been sought o r attended to

in fields other than medicine have and application of equations that will if the clinical patterns implicated by

pointed to the importance of an indi- be used. Similarly, the physical thera- this additional information were not

vidual's problem representation for pist's representation of the problem known to the student. The novice

guiding reasoning and determining (as determined by each individual's must rely on black and white text-

successful problem solution. A prob- personal perspective and organization book patterns and lacks information

lem representation is the solver's of knowledge) will influence the on the relationships and shared fea-

internal model of the problem, con- subsequent reasoning and search for tures across dfierent clinical pat-

taining the solver's conception of the a solution. For example, physical terns.3" This creates difficulty for the

problem elements, his or her knowl- therapists who adhere to the concept novice when confronted with irrele-

edge of those elements, and the rela- of "adverse neural tissue tension" as vant and unrelated information or

tionship the different problem ele- described by Elvey29 and Butler 30 will patient presentations containing over-

ments have to each other.25 The conceptually approach the examina- lapping problems and gray, nontext-

depth and organization of knowledge tion and treatment of a patient differ- book variations.

between novices and experts has ently than therapists without this par-

consistently been found to differ. ticular organization of knowledge. An example of the novice's risk of

Recognition of the continuity of the missing overlapping problems is the

Chess experts recognize patterns nervous system29,30will influence patient whose lateral elbow pain is

reflecting areas of strategic strength therapists' attention and weighting of aggravated by resisted extension of

and vulnerability and positions sup- patient clues and their subsequent the wrist. The novice may recognize

porting maneuvers of attack and de- search for supporting and negating this typical feature of injury to the

fense. Although the chess expert can data. common extensor origin yet fail to

replicate a chessboard when viewed exclude (through inquiry and physical

for only 5 seconds, there is a dramatic Using a method of propositional anal- tests) other potentially coexisting

drop-off in this ability below the level ysis to determine a clinician's mental disorders that may share o r predis-

of chess master. N o differences, how- representation of a case, Pate1 and pose to this clinical presentation (eg,

ever, are found when the chess pieces colleagues31-3' have found analogous involvement of C5-6 musculoskeletal

are randomly arranged, demonstrating results when comparing medical structures, adverse neural tissue ten-

the chess master's superior ability to clinicians at various levels of exper- sion, radiohumeral joint and local

perceive patterns in chess posi- tise. Typically, subjects are presented radial nerve entrapment).

ti0ns.26.~7Expert physics problem with a written patient description and

solvers represent problems as in- then asked to recall the facts in writ- Bordage and colleagues39~4~ have

stances of major laws of physics appli- ing, followed by their explanation of demonstrated other more qualitative

cable to the specific situation in the patient's underlying pathophysiol- differences in the organization of

which novices' problem representa- ogy and lastly their diagnosis. Proposi- novice and expert knowledge.

tion are more literal, fragmented, and tional analysis is a system of noting Whereas the novice's knowledge is

tied to overt features of the problem and classifying the clinician's observa- centered purely on disjointed lists of

such as the use of a spring or a pul- tions, findings, interpretations, and signs and symptoms, the stronger

ley.25 Similar results demonstrating inferences derived from the infoma- diagnosticians make use of abstract

experts' recognition of patterns have tion contained in the text. These stud- relationships such as proximal-distal,

been replicated in several other do- ies consistently demonstrated differ- deep-superficial, and gradual-sudden,

mains such as in the game of GO, in ences between experts' and novices' which assist to categorize similar and

reading circuit diagrams, in reading conceptualization of a problem, with opposing bits of information in

architectural plans, and in interpreting experts possessing a superior organi- memory.

Physical Therapy /Volume 72, Number 12Pecember 1992

One's organization of knowledge not lar. That is, in an attempt to under- be directed at the source of the symp-

only appears to determine what labels stand and manage the patient's prob- toms or toward contributing factors. If

are given to recognizable patterns of lem, I contend that therapists obtain passive movement is used, examples

information, but also includes "pro- information regarding the following of considerations include whether

duction rules," which specify what five categories of hypotheses: physiological or accessory movements

actions should be taken in different (1) source of the symptoms o r are used; whether pain should be

situations.23~32.41

Experts are thought dysfunction, (2) contributing factors, provoked o r avoided; and what direc-

to have a large number of such rules (3) precautions and contraindications tion, amplitude, speed, and duration

specific to their area of experience. to physical examination and treat- of movement should be applied.44

ment, (4) management, and

The end result of the expert's supe- (5) prognosis. Whereas epidemiological studies

rior organization of knowledge is the provide insight into the probable

ability to reason inductively in a for- These hypothesis categories are not course of different diseases and inju-

ward manner from the information peculiar to any particular approach or ries,45 physical therapists should be

presented and to achieve superior philosophy of manual therapy. Any able to inform patients to what extent

diagnostic accuracy. That is, when clinician who uses hypothetico- their disorder appears amenable to

confronting a familiar presentation, deductive clinical reasoning should physical therapy and to give an esti-

experts can utilize rules of action be considering hypotheses within mate of the time frame for which

found reliable in their own clinical each of these categories. recovery can be expected. Hypotheses

experience to reach a diagnosis based regarding "prognosis" in this sense

on pure pattern recognition. When "Source of the symptoms o r dysfunc- can only be made on the basis of

faced with an atypical problem o r a tion" refers to the actual structure each patient's individual presentation.

problem out of their area of exper- from which symptoms are emanating.

tise, however, experts, like novices, "Contributing factors" are any predis- Information leading to the different

must rely more on the hypothetico- posing or associated factors involved hypothesis categories is obtained

deductive (ie, hypothesis testing) in the development or maintenance throughout the subjective and physi-

method of reasoning.22.42~~3 of the patient's problem, whether cal examination, with any single piece

environmental, behavioral, emotional, of information often contributing to

The organization of knowledge rele- physical, or biomechanical. For exam- more than one hypothesis category.

vant to clinical manual therapy would ple, a subacromial structure may be A more detailed discussion of what

include the facts (eg, anatomy, patho- the source of the symptoms, whereas information can be considered for the

physiology, and so forth), procedures poor force production by the scapular different categories of hypotheses is

(eg, examination and treatment strate- rotators may b e the contributing fac- available in Jones5 and Jones and

gies), concepts (eg, instability, adverse tor responsible for the development Jones.46

neural tissue tension), and patterns of or maintenance of an "impingement"

presentation. This knowledge is uti- syndrome. Rothstein and Echternachj~~~ have

lized with the assistance of rules or proposed a useful hypothesis-oriented

principles (eg, selection of the grade Hypotheses regarding "precautions algorithm for clinicians. In highlight-

of passive movement and technique) and contraindications to physical ing the all-too-frequent occurrence of

to acquire, interpret, infer, and collate examination and treatment" serve to clinicians carrying out routine treat-

patient information. determine the extent of physical ex- ment plans that are unrelated to the

amination (ie, whether specific move- preceding patient examination, these

Clinlcal Reasoning in ments are performed or taken up to authors make a case for the need for

Physkal Therapy or into ranges of movement in which physical therapists to acquire clinical

pain is provoked and how many reasoning skills. They provide a clear

Whereas research in medical educa- movements are tested), whether phys- set of steps that appropriately high-

tion has emphasized diagnosis, I be- ical treatment is indicated, and, if so, light the importance of utilizing data

lieve that physical therapists must be whether there are constraints to phys- from the patient interview to generate

concerned with additional categories ical treatment (eg, the use of passive a problem statement and establish

of hypotheses in order to deliver movement without provoking any measurable goals. The algorithm

physical therapy effectively and safely. discomfort versus passive movement continues with the physical examina-

Therapists with different training will that provokes the patient's pain). tion and the generation of hypotheses

ask different questions and perform about the cause(s) of the patient's

different tests in accordance with the Hypotheses regarding "management" problem. They note that testing crite-

significance they give to the subjective include consideration of whether ria for each hypothesis should be

and physical information available physical therapy is indicated and, if considered and that all treatments

from the patient. I propose, however, so, what means should be trialed. If should relate to the hypotheses made.

that despite these differences, the manual therapy is warranted, it must The second part of their hypothesis-

aims of therapists' inquiries are simi- be decided whether treatment should oriented algorithm provides an or-

Physical Therapy /Volume 72, Number 12December 1992

patient shows obvious difficulty in

removing his o r her arm from a

jacket, the therapist will already be

forming initial hypotheses or working

INFORMATION

interpretations regarding the source

PERCEPTION

and of the problem and degree of involve-

INTERPRETATION ment. Further information (ie, data

collection) is then sought throughout

DATA the subjective and physical examina-

INITIAL CONCEPT ,or@ COLLECTION tion with these working hypotheses in

and ~nformatlon, ' s ~ b l e c t l v e mind.

MULTIPLE mdrd Interview

HYPOTHESES physlcal Although certain categories of infor-

examlnatlon

mation (eg, site, behavior, and history

of symptoms) are scanned in all pa-

EVOLVING tients, the specific questions pursued

CONCEPT 4

of the PROBLEM Information are tailored to each patient and the

(hypotheses therapist's evolving hypotheses. For

knowledge base modlfled) example, when the patient with d f i -

cognltlve skllls culty removing the jacket describes an

metacognltlve area of ache in the supraspinous fossa

skllls and an area of pain in the anterior

DECISION

dlagnostlc shoulder just lateral to the coracoid

management process, the initial hypothesis of a

"shoulder problem" is already modi-

fied. For me, two different symptoms,

an ache and a pain, are indicated,

PHYSICAL THERAPY each warranting consideration and

INTERVENTION

further inquiry. I would consider both

4 local and spinal structures as potential

REASSESSMENT sources o r contributing factors. The

patient's response to open questions

regarding what aggravates and what

Flgure. Clinical reasoning model for physical therapists. (Adaptedfrom Barrows eases the pain should then be inter-

and T ~ r n b l y n . ~ ~ ) preted with these hypotheses in mind.

dered series of steps for reassessing ing management. I have also Maitland**~~9 uses the phrase "make

the effects of the treatment imple- attempted to depict the cyclical char- the features fit" to encourage thera-

mented. This algorithm is useful in acter of the clinical reasoning process pists to inquire in the mode de-

teaching the hypothetico-deductive and to highlight key factors that influ- scribed here where information is

method of clinical reasoning and ence the various phases of clinical interpreted for its support or "fit"

assisting clinicians in recognizing reasoning. The process begins with with existing information (ie, working

when their actions have not been the therapist's obsavation and inter- hypotheses). When features do not fit,

logically formulated. pretation of initial cues from the or in this terminology your hypothe-

patient. Even in the opening moments sis is not supported by the new infor-

I have adapted a diagram from Bar- of greeting a patient, the therapist will mation, further inquiry is needed. For

rows and Tamblyn48 to depict the observe specific cues such as the example, an impingement of either

clinical reasoning process of physical patient's age, appearance, facial ex- contractile o r noncontractile struc-

therapists (Figure). This is not a sub- pressions, movement patterns, resting tures may be considered in the pa-

stitute for the hypothesis-oriented posture, and any spontaneous com- tient I have described. If further ques-

algorithm of Rothstein and Echter- ments. These initial cues from the tioning revealed that the patient had

nach.3.47 Rather, this model is pre- patient should cause the therapist to no difficulty lifting any weight below

sented to bring attention to the hy- develop an iniiial concept of the 90 degrees while movements across

pothesis generation, testing, and problem that includes prelimina y the body into horizontal flexion were

modification that I feel should take working hypotheses for consideration limited by the anterior pain, this

place through all aspects of the pa- through the rest of the examination would not, in my view, support a

tient encounter including the inter- and throughout ongoing management contractile tissue lesion but would

view, physical examination, and ongo- of the patient. For example, if the implicate an impingement of noncon-

tractile structures or an acromioclavic-

Physical Therapy /Volume 72, Number 12iDecember 1992

ular source to this pain. I would ques- additional examination, reanalysis of Errors of Clinlcal Reasonlng

tion and reason in this manner to data obtained, referral to another

assess the involvement of other struc- health care practitioner). Successful management of a patient's

tures in the anterior pain, such as problem requires a multitude of

cervical structures and neural tissues, Factors lnfluenclng Cllnlcal skills. Working from the patient's

and I would pay equal attention to Reasonlng account of the problem, the therapist

the ache. must be able to efficiently observe

The clinical reasoning process is influ- and extract information, distinguish

Similarly, the physical examination is enced by the therapist's knowledge relevant from irrelevant information,

not simply a routine series of tests. base, cognitive skills (eg, data analysis make correct interpretations, weigh

There may be specific physical tests and ~ynthesis),~6~*~~5~ and metacogni- and collate information, and draw

that are used for different areas, but tive skills (ie, awareness and monitor- correct inferences and deductions.

these should be seen as an extension ing of thinking processes).5l These Errors of reasoning may occur at any

of the data collection and hypothesis factors influence all aspects of the stage of the clinical reasoning process

testing performed through the subjec- clinical reasoning process and can including errors of perception, in-

tive e ~ a m i n a t i o nFor

. ~ ~example, re- themselves be improved when thera- quiry, interpretation, synthesis, plan-

ports of painful "clicking" in the pists consciously reflect on the sup- ning, and reflection. Application of

shoulder and sensations of apprehen- porting and negating information on hypothesis-oriented clinical reasoning

sion indicate the need for instability which their inquiries and clinical as encouraged by the clinical reason-

and labral integrity testing, but these decisions are based. For example, ing model portrayed in the Figure

tests may not be warranted in the consideration of the features of the and the hypothesis-oriented algorithm

next patient who has similar patient's presentation that fit and do described by Rothstein and Echter-

symptoms. not fit existing patterns recognized by nach4' should assist clinicians in

therapists will enable therapists to avoiding errors of reasoning.

This process of data collection contin- learn about different clinical patterns

ues as hypotheses are refined and and their variations and to broaden Examples of reasoning errors extrapo-

reranked and new ones considered in their knowledge base. I contend that lated from Nickerson et alsl are given

the therapist's "evolving concept" of therapists with good clinical reason- below with the physical therapy appli-

the problem. The clinical reasoning ing skills will reflect as they interact cations derived by this author.

through the patient examination con- with the patient, improvising their

tinues until sufficient idormation is actions in accordance with the unfold- 1. Adding pragmatic inferences. Mak-

obtained to make a "diagnostic" and ing patient findings much like a musi- ing assumptions is an error of

management decbion. cian adjusts his o r her performance reasoning. For example, a patient

when participating in an improvisa- with pain in the supraspinous fossa

The clinical reasoning process does tional session with other musicians.52 will often describe this as "pain in

not stop at completion of the patient my shoulder." It is a misrepresen-

examination. Rather, the therapist will As reasoning is only as good as the tation of the facts to assume the

have reached the management deci- information on which it occurs, any patient's "shoulder pain" is actually

sions of whether to treat o r not treat; factor influencing the reliability and within the shoulder itself without

whether to address the source(s) o r validity of information obtained (eg, specific clarification of the site.

contributing factor@),or both, ini- communication/interpersonal and

tially; which mode of treatment to use manual skills) will also influence the 2. Considering too fa0 hypotheses. By

initially; and, if passive movement effectiveness of one's clinical reason- prematurely limiting the hypotheses

treatment is to be used, whether to ing. For example, leading questions in considered, discovery of the correct

provoke symptoms and the direction a patient interview often elicit re- hypothesis may be missed or de-

and grade of movement. Every treat- sponses that support the examiner's layed. This can occur when inqui-

ment, whether it is hands-on o r ad- assertion. Other less tangible factors ries and physical tests are only

vice, should be a form of hypothesis influencing clinical reasoning include directed to the local sources of a

testing. Continual reassessment is environmental contingencies such as patient's symptoms, as with the

essential and provides the evidence group norms and time constraints.*l patient reporting "shoulder pain

on which hypotheses are accepted or That is, working environments of with any lifting." To interpret this

rejected. Reassessmmt should contrib- overextended case loads and peer or automatically as a shoulder problem

ute to the therapist's evolving concept self-imposed pressure to exclusively or, worse yet, a "frozen shoulder"

of the patient's problem. When treat- adopt the latest treatment fad are not without considering other hypothe-

ment has not had the expected effect, conducive to clinical reasoning that is ses is an error of reasoning.

the therapist's concept of the problem hypothesis oriented.

and its management may be altered, 3. Failure to sample enough irzformu-

leading to a change in treatment o r tion. It is an error to make a gen-

further inquiry (eg, reexamination, eralization based o n limited data.

Physical Therapy 'Volume 72, Number 12Pecember 1992

This is seen in judgments regard- time as a central neck pain is insuf- lesions, there will typically be pain

ing the success o r failure of a par- ficient to judge the relationship of on resisted isometric testing; how-

ticular management approach these symptoms. A full understand- ever, this does not mean that all

based on only a few experiences. ing of the relationship between painful resisted isometric tests are

Closely linked to this error is the these two symptoms requires in- necessarily intrinsic rotator cuff

failure to sample information in an quiry of when both occur together, lesions.

unbiased way. Although this is when the neck pain occurs without

typically controlled for in formal the scapular pain, when the scapu- A second form of deductive rea-

research, the practicing therapist lar pain occurs without the neck soning states: If A, then B; not B,

will rely on memory of previous pain, and when neither neck nor therefore not A. For example, if

experiences as the sample on scapular pain are occurring. you have shoulder pain referred

which views are based. The error from the cervical spine, you will

occurs when only those cases are 6. Confusing covariance with causal- have cervical signs; if you do not

recalled that support one view ity. When two factors have been have cervical signs, it is not cervical

while confounding evidence is found to covary, it is an error to referred shoulder pain. It is a de-

forgotten. deduce the factors are necessarily ductive error to reason: If A, then

causally related. For example, if the B; not A, therefore not B. For ex-

4. Confirmution bias. Another error scapular pain in the above example ample, if you have shoulder pain

of reasoning related to a biased only occurs when the cervical pain referred from the cervical spine,

sample of information occurs when is present, this does not prove the you will have cervical signs; if

therapists only attend to those two symptoms are from the same there is no cervical referred shoul-

features that support their favorite source (eg, cervical disk). Although der pain, there will not be cervical

hypotheses while neglecting the this is a reasonable hypothesis, signs.

negating features. This can lead to another possibility is that two dif-

incorrect clinical decisions and ferent structures (eg, cenical and 8. Premise conversion. It is a deduc-

hinder the therapist's opportunity thoracic) are simultaneously tive error of reasoning to reverse a

to learn different variations of clini- stressed by the same activity or statement of categorization. That is,

cal patterns. For example, a pre- posture. all A are B does not mean all B are

sentation of central low back pain A. For example, all shoulder im-

aggravated by slouched sitting may 7 . Conjksion between deductive and pingements are subacromial (or

be quickly interpreted by some inductive logic. Deductive reason- subcoracoid) does not mean

therapists to be a "diskogenic" ing involves logical inference. One all subacromial pains are

disorder. Further clarification that draws conclusions that are a logi- impingements.

the patient's pain provocation was cal, necessary consequence of the

not time dependent and that move- premises without going beyond the These examples represent only a

ment from a sitting to a standing information contained in the prem- sample of the reasoning errors a

position was not hindered, regard- ises. Correct deductive reasoning is therapist can make. Errors in reason-

less of the speed at which it was independent of the truth of the ing are also not confined to the less

performed, could represent negat- premises o r the conclusion. In experienced, as even "experts" have

ing features to the "diskogenic" contrast, inductive reasoning in- been shown to overemphasize posi-

diagnosis. Attention to such varia- volves going beyond the informa- tive findings, ignore or misinterpret

tions in presentation will assist tion given. Every time we make a negative findings, deny findings that

therapists' recognition of clinical generalization based on specific conflict with a favorite hypothesis, and

variations within the same diagno- observations, this is an induction. obtain redundant information.16.52-54

sis, which in turn should lead to A valid form of deductive reason- The As and Bs of logic may appear to

recognition of optimal treatment ing states: If A, then B; A, therefore be nothing more than semantics. If

strategies for the respective B. For example, if you have an the inductive generalizations preva-

presentations. acromioclavicular joint problem, lent in manual therapy are not recog-

horizontal flexion is likely to be nized for what they are, however,

5. E m r s in detecting covariance. To symptomatic. It is a deductive error therapists are prone to accept these

make a judgment about the rela- to reason: If A, then B; B, therefore generalizations as fact and fail to look

tionship of two factors requires A. For example, if you get pain for alternative explanations.

understanding of how the two with horizontal flexion you have an

factors covary with one another. It acromioclavicular joint problem. Bordage and c o l l e a g ~ e s ~ ~suggest

,5~5~

is an error to make this judgment This may be inductively reasonable that most diagnostic errors are not

based solely on one combination based on past experience; how- the result of inadequate medical

of covariance. For example, know- ever, it is deductively wrong, as knowledge as much as an inability to

ing that the patient's medial scapu- other structures may be responsi- retrieve relevant knowledge already

lar pain is experienced at the same ble. Similarly, with rotator cuff stored in memory. That is, the

Physical Therapy /Volume 72, Number

amount of knowledge appears less physical therapy organization of closely linked to the accessibility of

relevant than the organization of that knowledge necessitates further inves- one's knowledge. Knowledge that is

knowledge. When knowledge is not tigation of potential differences in acquired in the context for which it

organized in clinically relevant pat- clinical reasoning and associated will be used becomes more accessi-

terns, it becomes less accessible in factors. ble.72,73Although clinical knowledge

the clinical setting. is typically presented in the context of

Facllltating Cllnlcal Reasoning patient problems, this is less com-

Having given the impression that in Our Students monly the case with the basic sci-

good clinical reasoning will assist ences (eg, pathophysiology). Ap-

therapists in recognizing clinical pat- As physical therapists have taken proaches to physical therapy

terns, a word of caution regarding greater responsibility in patient man- education in which the acquisition of

excessive attention to clinical patterns agement, especially with the increased knowledge is facilitated by teaching

I

is needed. Clinical patterns are at risk autonomy associated with first-contact centered on patient problems pro-

of becoming rigidly established when practice, physical therapy education vide, in my opinion, the ideal envi-

the patterns themselves control our ha. respbnded with efforts to produce ronment for building an accessible I

attention. I believe this leads to errors more "thinking" therapists. Although organization of knowledge and foster- I

of limited hypotheses and insufficient attention to clinical reasoning skills ing clinical reasoning ~kills.67~68,7-1

sampling where anything that has any has presumably always been inherent

resemblance to a standard pattern will in our physical therapy education, Learning the hypothesis testing ap-

be seen as that pattern. For example, there has been a more recent interest proach also enables students to con-

the information that a patient has pain in providing more formal and focused tinue to learn beyond their formal

in the area of the greater trochanter learning experiences specifically education. Rather than relying on a

aggravated by functional movements aimed at facilitating clinical reasoning text or more experienced colleague

involving flexion or adduction of the in physical therapy students.*.5aGS69 to learn new clinical patterns, the

hip may cause some therapists to therapist who actively reasons

hypothesize the existence of a "hip Facilitating students' clinical reasoning through and reflects on patient prob-

joint" disorder. Limiting one's hypoth- requires making them aware of their lems will continually challenge exist-

eses to what may appear to be the own reasoning process and designing ing patterns and in the process ac-

most obvious hypothesis without learning experiences that promote all quire new ones.

pursuing additional supporting o r aspects of the clinical reasoning pro-

negating evidence prevents the thera- cess while exposing the errors in Summary

pist from ever learning the pattern of reasoning that occur. This requires

other disorders that may share fea- access to students' thoughts and feed- Early research in medical education

tures with a disorder of the hip (eg, back on thinking processes. That is, provided a picture of a clinical rea-

lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint, adverse students should be taught to think soning process that was hypothetico-

neural tissue tension) or the full and to think about their thinking.70 deductive and universally applied by

range of presentations a hip joint This can be achieved by promoting clinicians at all levels of experience.

disorder can manifest. students' use of reflection to encour- The differentiating feature of expert

I age awareness and promote integra- diagnosticians and novices appears to

Implkatlons for Physkal tion of existing versus new knowl- lie in their organization of knowl-

Therapists edge. When combined with a better edge. Experts have a superior organi-

awareness of one's own cognitive zation of knowledge that enables

Physlcal Therapy Research in processes (ie, metacognition), the them to reason inductively in a form

Cllnlcal Reasoning students' processing of information is of pattern recognition. When con-

enhanced and clinical reasoning is fronted with unfamiliar problems, the

Consideration of the clinical reason- facilitated. Learning experiences to expert, like the novice, will rely on

ing literature outside of physical ther- facilitate clinical reasoning using both the more basic hypothesis testing

apy assists in developing an under- reflection and metacognition are approach to clinical reasoning.

standing of this topic while providing described else~here.5~71

educational and clinical extrapolations Research to better understand the

to our profession. Debate continues The process of reasoning should not, clinical reasoning and nature of ex-

in the medical literature, however, in my view, be addressed to the ne- pertise in physical therapy can assist

regarding the nature of expertise and glect of knowledge. Rather, facilitating us in designing learning experiences

the appropriate methodology to use the clinical reasoning process will to facilitate clinical reasoning. Clinical

in research.4015-3 Although some assist the students' acquisition of reasoning is now being given specific

evidence does exist suggesting that knowledge. In turn, good organiza- attention in some physical therapy

medical and physical therapy clinical tion of knowledge leads to better education programs. The aims of

reasoning processes are similar,- the clinical reasoning. The importance of these programs should be to increase

potential differences in medical and one's organization of knowledge is students' awareness of their clinical

Physical Therapy,/Volume 72, Number 12December 1992

reasoning and to foster development Therapy, May 17-22, 1987; Sydney, New South 24 Newell A, Simon HA. Human Problem

Wales, Australia. 1987:543-551. Solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall;

of both reasoning and knowledge 1972.

8 Thomas-Edding D. Clinical problem solving

through learning experiences cen- in physical therapy and its implications for 25 Chi MTH, Feltovich PJ, Glaser R. Categori-

tered on patient problems. This re- curriculum development. In: Proceedings of zation and representation of physics problems

quires accessing students' thoughts the Tenth International Congress of the World by experts and novices. Cognitive Science.

Confederation for Physical Therapy; May 17- 1981;5:121-152.

during and after a patient encounter 22, 1987; Sydney, N m South Wales, Australia. 26 DeGrcmt AD. Thought a n d Choice in Chess.

and providing feedback on errors of 1987:10@104. New York, NY Basic Books; 1965.

reasoning that emerge. Teaching 9 Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence 27 Chase WG, Simon HA. Perception in chess.

students skills of reflection and meta- a n d Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Cognitive Psychology 1973;4:5541.

Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley; 1984. 28 Glaser R, Chi MTH. Overview. In: Chi

cognition should improve their clini- 10 Downie J, Elstein AS, eds. Profesn'onal MTH, Glaser R, Farr MJ, eds. The Nature of

cal reasoning now and equip them Judgment: A Reader in Clinical Decision Mak- Expertise. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum As-

with the: means to continue learning ing. New York, W, Cambridge University sociates Inc; 1988:xv-xxxvi.

Press; 1988. 29 Elvey RL. Treatment of arm pain associated

from future patient problems. Thera-

11 Nickerson RS, Perkins DN, Smith EE. The with abnormal brachial plexus tension. Austra-

pists can improve their own clinical Teaching of Thinking. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence lian Journal of ~ b ~ s i o t h k r 1986;32:224

a~~.

reasoning by stopping at various Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1985. 229.

points through a patient examination 12 Chi MTH, Glaser R, Farr MJ, eds. The Nu- 30 Butler DS. Mobilization of the Nervous

and the ongoing management period ture of Expertise. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Ed- System. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Church-

baum Associates Inc; 1988. ill Livingstone: 1991.

to consciously reflect on hypotheses 1 3 Thomas SA, Wearing AJ, Bennett MJ. Clini- 31 Patel VL, Frederiksen CH. Cognitive p r e

being considered, implications of cal Decision Making for Nurses a n d Health cesses in comprehension and knowledge ac-

those hypotheses, and, in hindsight, Professionals. Sydney, New South Wales, Aus- quisition by medical students and physicians.

tralia: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1991. In: Schmidt HG, DeVolder ML, eds. Tutorials

where e:rrors of reasoning occurred. in Problem-Based Learning. Assen, the Nether-

14 Elstein AS. Cognitive processes in clinical

Clinical reasoning that is hypothesis inference and decision making. In: Turk DC, lands: Van Gorcum BV; 1984;14>157.

directed and open-minded can add to Salovey P, eds. Reasoning, Inference, a n d 32 Pate1 VL, Groen GJ. Knowledge-based solu-

our organization of knowledge and Judgment in Clinical Psychology. New York, tion strategies in medical reasoning. Cognitive

NY: The Free Press; 1988:17-50. Science. 1986;10:91-108.

enhance the quality and accountability 15 Feltovich PJ, Barrows HS. Issues of general- 33 Patel VL, Groen GJ, Frederiksen CH. Differ-

of our patient care. ity in medical problem solving. In: Schmidt ences between medical students and doctors

HG, DeVolder ML, eds. Tutorials in Problem- in memory for clinical cases. Med Educ. 1986;

Acknowledgment Based Learning Assen, the Netherlands: Van 20:3-9.

Gorcum BV; 1984:128-141. 34 Coughlan LD, Patel VL. Processing of criti-

1 6 Elstein AS, Shulman IS,Sprafka SS. Medi- cal information by physicians and medical stu-

I would like to thank Dr Joy Higgs, cal Problem Solving: An Analysis of Clinical dents. J Med Educ. 1987;62:81&828.

Head, School of Physiotherapy, Fac- Reasoning. Cambridge, Mass; Harvard Univer- 35 Patel VL, Evans DA, Groen GJ. Biomedical

ulty of Health Sciences, University of sity Press; 1978. knowledge and clinical reasoning. In: Evans

Sydney, for her review and sugges- 17 Barrows HS, Feightner JW, Neufeld VR, DA, Patel VL, eds. Cognitive Science in Medi-

Norman GR. Analysis of the Clinical Methods cine. London, England: The MIT Press Ltd;

tions in the development of this of Medical Students a n d Physicians: Final Re- 1989:53-112.

manuscript. port. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Ontario De- 36 Patel VL, Evans DA, Kaufman DR. A cogni-

partment of Health; 1978. tive framework for doctor-patient interaction.

18 Barrows HS, Norman GR, Neufeld VR, In: Evans DA, Patel VL, eds. Cognitive Science

References Feightner JW. The clinical reasoning of ran- in Medicine. London, England: The MIT Press

domly selected physicians in general medical Ltd; 1989:257-312.

practice. Clin Invest Med. 1982;5:49-55. 37 Patel VL, Groen GJ, Arocha JF. Medical ex-

1 Wolf SL, ed. Clinical Decision Making in

Physical Therapy. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis 19 Neufeld VR, Norman GR, Feightner JW, pertise as a Function of task difficulty. Memory

Barrows HS. Clinical problem-solving by medi- a n d Cognition. 1990;18:394-406,

Co; 1985.

cal students: a cross-sectional and longitudinal 3 8 Feltovich PJ, Johnson PE, Moller JH, Swan-

2 Grant R, Jones MA, Maitland GD. Clinical analysis. Med Educ. 1981;15:315-322.

decision making in upper quadrant dysfunc- son DB. LCS: the role and development of

tion. In: Grant R, ed. Physical Therapy of the 20 Norman GR, Tugwell P, Feightner JW.A medical knowledge in diagnostic expertise. In:

Cervical a n d Thoracic Spine. New York, NY: comparison of resident performance on real Clancey WJ, Shortliffe EH, eds. Readings in

Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1988:51-79. and simulated patients. J Med Educ. 1982;57: Medical Ar12Jicial InleN@ence: The Firsl Dec-

708-715. ade. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley; 1983:275

3 Echternach JL, Rothstein JM. Hypothesis-

21 Patel VL, Groen GJ. The general and spe- 319.

oriented algorithms. Phys Ther 1989;69:559-

564. cific nature of medical expertise: a critical 39 Bordage G, Lemieux MA. Some cognitive

look. In: Ericsson A, Smith J, eds. Toward a characteristics of medical students with and

4 Shepard KF, Jensen GM. Physical therapist General Theory of Expertise: Prospects a n d without diagnostic reasoning difficulties. In:

curricula for the 1990s: educating the reflec- Limits. New York, NY: Cambridge University Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference

tive pracl.itioner.Phys Ther. 1990;70:566-577. Press; 1991:93-125. o n Research in Medical Education; 1986;New

5 Jones MA. Clinical reasoning process in ma- 22 Groen GJ, Pate1 VL. A view from medicine. Orleans, Louisiana. 1986:185-190.

nipdative therapy. In: Boyling JD, Palastanga In: Smith M, ed. Toward a UniJied Theory of 40 Bordage G, Grant J, Marsden P. Quantita-

N, eds. Modern Manual Therapy: The Vertebral Problem Solving: Views from Content Do- tive assessment of diagnostic ability. Med Educ.

Column. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill mains. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associ- 1990;24:413425.

Livingstone. In press. ates Inc; 1990:35-44. 41 Patel VL, Groen GJ. Developmental ac-

6 Payton OD. ClinicaI reasoning process in 23 Greeno JG, Simon HA. Problem solving counts of the transition from medical student

physical therapy. Phys T k . 1985;65:92&928. and reasoning. In: Atkinson RC, Hernstein R, to doctor: some problems and suggestions.

7 Dennis JK, May BJ. Practice in the year 2000: Lindsey G, Luce RD, eds. Steven's Handbook of Med Educ. 1991;25:527-535.

expert decision making in physical therapy. In: Experimental Psychology, Volume 2: Learning 42 Elstein AS. Shulman LS, Sprafka SA. Medi-

Proceedings of the Tenth International Con- a n d Cognition. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John cal problem solving: a ten-year retrospective.

gress of the World Confederation for Physical Wiley & Sons Inc; 1986:589-572.

Physical Therapy /Volume 72, Number 12December 1992

Evaluation and the Health Profes~ions.1990; atory study. In: Proceedings of the 21sr Confer- 69 Terry W, Higgs J. Educational programs to

13:>36. ence on Research in Medical Education; 1982; develop clinical reasoning skills. Australian

43 Barrows HS, Feltovich PJ. The clinical rea- Washington, DC.1982:171-176. Journal of Physiotherapy. In press.

soning pmess. Med Educ. 1987;21:8691. 56 Bordage G, Zacks R. The structure of medi- 7 0 Schon DA. Educating the Refective Practi-

44 Maitland GD. Peripheral Manipulation. 3rd cal knowledge in the memories of medical tioner. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Pub-

ed. London, England: Butterwonh & Co (Pub- students and general practitioners: categories lishers; 1990.

lishers) Ltd; 1991. and prototypes. Med Educ. 1984;18:406416. 7 1 Higgs J. Developing knowledge: a process

45 Jeffreys E. Prognosis in Musculoskeletal 5 7 Bordage G, Lemieux M. Semantic struc- of construction, mapping and review. New

Injury: A Handbook for Doctors and Lawyers. tures and diagnostic thinking of experts and Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy. In press.

London, England: Butterwonh & Co (Publish- novices. Acad Med. 1991;66(suppI):S7&S72. 72 Tulving E, Thomson DM. Encoding speci-

ers) Ltd; 1991. 5 8 Berner ES. Paradigms and problem-solving: ficity and retrieval processes in episodic mem-

46 Jones MA, Jones HM. Principles of the a literature review. J Med Educ. 1984;59:62> ory. Psycho1 Rev. 1973;80:352-373.

physical examination. In: Boyling JD, Pa- 633. 7 3 Rumelhan DE, Onony E. The representa-

lastanga N, eds. Modern Manual Therapy: The 59 McGuire C. Medical problem-solving: a tion of knowledge in memory. In: Anderson

Vertebral Column. 2nd ed. London, England: critique of the literature. In: Proceedings of the RC, Spiro RJ, Montague WE, eds. Schooling

Churchill Livingstone. In press. 23rd Annual Conference on Research in Medi- and the Acquisition of Knowledge. Hillsdale,

47 Rothstein JM, Echternach JL. Hypothesis- cal Education; 1984; Washington, DC 1984:3- NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum A5sociates Inc; 1977':s-

oriented algorithm for clinicians: a method for 12. 135.

evaluation and treatment planning. Phys Ther. 6 0 Groen GJ, Patel VL. Medical problem- 74 Barr JS. A problem-solving curriculum de-

1986;66:138%1394. solving: some questionable assumptions. Med sign in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1977;57:

48 Barrows HS, Tamblyn RM. Problem-Based Edw. 1985;19:95-100. 262-270.

Learning: An Approach to Medical Education. 6 1 Norman GR. Problem-solving skills, solving 75 May BJ. An integrated problem-solving cur-

New York, NY:Springer-Verlag New York Inc; problems and problem-based learning. Med riculum design for physical therapy education.

1980. Educ. 1988;22:279-286. Phys Ther. 1977;57:807-813.

49 Maitland GD. Vertebral Manipulation. 5th 62 Barrows HS. Inquiry: the pedagogical im- 7 6 May BJ. Evaluation in a competency-based

ed. London, England: Butterwonh & Co (Pub- portance of a skill central to clinical practice. educational system. Phys Ther. 1977;57:2%33.

lishers) Ltd; 1986. Med Educ. 1930;24:3-5. 7 7 Olsen SL. Teaching treatment planning. a

50 Gale J. Some cognitive components of the 6 3 Norman GR, Pate1 VL, Schmidt HG. Clinical problem-solving model. Phys Ther 1983;63:

diagnostic thinking process. Br J Educ Psychol. inquiry and scientific inquiry. Med Educ. 1990; 526529.

1982;52:64-76. 24:396399. 7 8 Titchen AC. Design and implementation of

51 Nickerson RS, Perkins DN, Smith EE. The 64 Denton B, Jensen GM. Reflective inquiry: a a problem-based continuing education pro-

Teaching of Thinking. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence suggestion for clinical education. Phys Ther. gramme. Physiotherapy. 1987;73:31%323.

Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1985:10&109. 1989;69:407.Abstract. 79 Titchen AC. Problem-based learning: the

52 Schon DA. The Refective Practitioner: How 65 Jones MA. Clinical reasoning process in rationale for a new approach to physiotherapy

Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: manipulative therapy. In: Proceedings of the continuing education ~hysiotherap~. 1987;73:

Basic Books; 1983. International Federation of Orthopaedic Ma- 324-327.

53 Lesgold A, Rubinson H, Feltovich P, et al. nipulative Therapists Congress;September 4-9, 8 0 Burnett CN, Pierson FM. Developing

Expenise in a complex skill: diagnosing x-ray 1988; Cambridge, England 1988:29-30. problem-solving skills in the classroom. Pbys

pictures. In: Chi MTH, Glaser R, Farr M, eds. 66 Jones MA. Clinical Reasoning in Manipula- Ther. 1988;69:441447.

The Nature of Expertise. Hillsdale, NJ: tive Therapy Education. Adelaide, South Aus- 81 Slaughter DS, Brown DS, Garder DL, Per-

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc: 1981:311- tralia, Australia: South Australian Institute of ritt LJ. Improving physical therapy students'

342. Technology; 1989. Master's thesis. clinical problem-solving skills: an analytical

54 Voytovich AE, Rippey RM, Suffredini A. Pre- 67 Higgs J. Fostering the acquisition of clinical questioning model. Phys Ther 1989;69:441-

mature conclusions in diagnostic reasoning. reasoning skills. New Zealand Journal of Phys- 447.

J Med Educ. 1985;60:302-307. iotherapy. 1990;18:13-17.

55 Bordage G, Allen T.The etiology of diag- 68 Higgs J. Developing clinical reasoning

nostic errors: process or content? An explor- competencies. Physiotherapy. In press.

Physical Therapy/Volume 72, Number 12December 1992

View publication stats

You might also like

- Foundations of Professional Psychology: The End of Theoretical Orientations and the Emergence of the Biopsychosocial ApproachFrom EverandFoundations of Professional Psychology: The End of Theoretical Orientations and the Emergence of the Biopsychosocial ApproachNo ratings yet

- Dimensional PsychopathologyFrom EverandDimensional PsychopathologyMassimo BiondiNo ratings yet

- Clinical reasoning in manual therapyDocument10 pagesClinical reasoning in manual therapyPhooi Yee LauNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning - Jones PDFDocument12 pagesClinical Reasoning - Jones PDFIsabelGuijarroMartinezNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning: Linking Theory To Practice and Practice To TheoryDocument14 pagesClinical Reasoning: Linking Theory To Practice and Practice To Theorylumac1087831No ratings yet

- Original Research: Patterns of Clinical Reasoning in Physical Therapist StudentsDocument13 pagesOriginal Research: Patterns of Clinical Reasoning in Physical Therapist StudentsNishtha singhalNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning Strategies in PTDocument19 pagesClinical Reasoning Strategies in PTamitesh_mpthNo ratings yet

- Single-Case Research Designs in Clinical Child Psychiatry: Journal of The American Academy of Child PsychiatryDocument10 pagesSingle-Case Research Designs in Clinical Child Psychiatry: Journal of The American Academy of Child PsychiatryKarla SuárezNo ratings yet

- He Clinical Integrative Puzzle For Teaching and Assessing Clinical Reasoning Preliminary Feasibility, Reliability, and Validity EvidenceDocument7 pagesHe Clinical Integrative Puzzle For Teaching and Assessing Clinical Reasoning Preliminary Feasibility, Reliability, and Validity EvidenceFrederico PóvoaNo ratings yet

- Pincus 2006Document9 pagesPincus 2006Claudio Andrés Olmos de AguileraNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Assessment of Clinical Reasoning: Omar S. LaynesaDocument20 pagesUnderstanding The Assessment of Clinical Reasoning: Omar S. Laynesaomar laynesaNo ratings yet

- Medscimonit 17 1 Ra12.pdf WT - SummariesDocument2 pagesMedscimonit 17 1 Ra12.pdf WT - SummariesRin VaelinarysNo ratings yet

- Clinical ReasoningDocument23 pagesClinical Reasoningathe_triiaNo ratings yet

- Physical Therapist As Critical InquirerDocument39 pagesPhysical Therapist As Critical InquirerMichels Garments S.H Nawaz HosieryNo ratings yet

- How Physicians Manage Medical Uncertainty: A Qualitative Study and Conceptual TaxonomyDocument17 pagesHow Physicians Manage Medical Uncertainty: A Qualitative Study and Conceptual TaxonomyAlexNo ratings yet

- Clinical reasoning for MSK PTsDocument48 pagesClinical reasoning for MSK PTsCatalina MusteațaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Clinical Reasoning Three EvolutionsDocument6 pagesAssessment of Clinical Reasoning Three EvolutionsFrederico PóvoaNo ratings yet

- A Universal Model of Diagnostic Reasoning.14Document7 pagesA Universal Model of Diagnostic Reasoning.14Emília SantocheNo ratings yet

- Defining and Assessing Professional Competence: ReviewDocument10 pagesDefining and Assessing Professional Competence: ReviewJeaniee Zosa EbiasNo ratings yet

- UGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedDocument3 pagesUGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedAlicia WellmannNo ratings yet

- Context and Clinical ReasoningDocument8 pagesContext and Clinical ReasoningFrederico PóvoaNo ratings yet

- AConciseGuidetoClinicalReasoning PrepublicationDocument23 pagesAConciseGuidetoClinicalReasoning PrepublicationAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Timm Step by StepDocument6 pagesTimm Step by StepPutu WirasatyaNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking in Respiratory Care Practice PDFDocument17 pagesCritical Thinking in Respiratory Care Practice PDFFernando MorenoNo ratings yet

- Evidence based-WPS OfficeDocument6 pagesEvidence based-WPS OfficeSalima HabeebNo ratings yet

- Defining and Assessing Professional Competence: JAMA The Journal of The American Medical Association February 2002Document11 pagesDefining and Assessing Professional Competence: JAMA The Journal of The American Medical Association February 2002NAYITA_LUCERONo ratings yet

- What S in A Case Formulation PDFDocument10 pagesWhat S in A Case Formulation PDFNicole Flores MuñozNo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy: Neil Langridge, Lisa Roberts, Catherine PopeDocument6 pagesManual Therapy: Neil Langridge, Lisa Roberts, Catherine PopeVizaNo ratings yet

- Piramide ClinicaDocument6 pagesPiramide ClinicaJASER MILTON ISMAEL MALDONADO GUERRERONo ratings yet

- Updated Integrated FrameworkDocument17 pagesUpdated Integrated FrameworkE. Jimmy Jimenez TordoyaNo ratings yet

- Updated Integrated Framework For Making Clinical Decisions Across The Lifespan and Health ConditionsDocument13 pagesUpdated Integrated Framework For Making Clinical Decisions Across The Lifespan and Health ConditionsmaryelurdesNo ratings yet

- Transdiagnostic FormulationDocument9 pagesTransdiagnostic FormulationMariela Del Carmen Paucar AlbinoNo ratings yet

- EBP in Adults FinalDocument20 pagesEBP in Adults FinalTony JacobNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Case Studies in Massage Therapy CliniDocument5 pagesFacilitating Case Studies in Massage Therapy ClinijorgenovachrolloNo ratings yet

- PublishedEBParticle JournalofAlliedHealth CardinDocument11 pagesPublishedEBParticle JournalofAlliedHealth Cardinag wahyudiNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Versus Clinical Reasoning Versus Clinical JudgmentDocument3 pagesCritical Thinking Versus Clinical Reasoning Versus Clinical JudgmentWinda ArfinaNo ratings yet

- Clinical ReasoningDocument3 pagesClinical ReasoningIvy VihNo ratings yet

- EBP Nursing ResearchDocument4 pagesEBP Nursing ResearchFrances BañezNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Patient Safety in Mental HealthDocument7 pagesEnhancing Patient Safety in Mental Healthruba azfr-aliNo ratings yet

- Needs Assessment For Holistic Health Providers Using Movement As MedicineDocument10 pagesNeeds Assessment For Holistic Health Providers Using Movement As Medicineapi-399928223No ratings yet

- Kazdin, 2008Document14 pagesKazdin, 2008CoordinacionPsicologiaVizcayaGuaymasNo ratings yet

- Case Formulation in PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesCase Formulation in PsychotherapySimona MoscuNo ratings yet

- Cooke2017 Transforming Medical AssessmentDocument6 pagesCooke2017 Transforming Medical AssessmentbrecheisenNo ratings yet

- 1 Running Head: Research Methods and ApproachesDocument6 pages1 Running Head: Research Methods and ApproachesGeorge MainaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning in Dentistry: A Conceptual Framework For Dental EducationDocument13 pagesClinical Reasoning in Dentistry: A Conceptual Framework For Dental EducationDrSanaa AhmedNo ratings yet

- Physical Therapy Research Paper SampleDocument8 pagesPhysical Therapy Research Paper Sampleaflbqewzh100% (1)

- 10 1111@jhn 12820Document10 pages10 1111@jhn 12820Federico CilloNo ratings yet

- The Use of Clinical Trials in Comparative Effectiv PDFDocument9 pagesThe Use of Clinical Trials in Comparative Effectiv PDFSilverio CasillasNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practice in Pediatric Physical Therapy by BarryDocument14 pagesEvidence-Based Practice in Pediatric Physical Therapy by BarryFe TusNo ratings yet

- ActivityDocument2 pagesActivitysanchezanya34No ratings yet

- Methuselah-An Expert System For Diagnosis in Geriatric PsychiatryDocument12 pagesMethuselah-An Expert System For Diagnosis in Geriatric PsychiatryMilton MurilloNo ratings yet

- Meta Analysis Nursing Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesMeta Analysis Nursing Literature Reviewea46krj6100% (1)

- scholarly capstone paperDocument5 pagesscholarly capstone paperapi-738778945No ratings yet

- The Effect of Reducing The "Jumping To Conclusions"Document10 pagesThe Effect of Reducing The "Jumping To Conclusions"treyhanNo ratings yet

- Richards Et All (2020) Enseñanza ClínicaDocument33 pagesRichards Et All (2020) Enseñanza ClínicaCandela AriasNo ratings yet

- Van Scoyoc, S. (2017) - The Use and Misuse of Psychometrics in Clinical Settings. in B. Cripps (Ed.)Document17 pagesVan Scoyoc, S. (2017) - The Use and Misuse of Psychometrics in Clinical Settings. in B. Cripps (Ed.)susanvanscoyoc9870No ratings yet

- EBPDocument15 pagesEBPGaje SinghNo ratings yet

- ARTG - 2011 - PT Practice in Acute Care SettingDocument14 pagesARTG - 2011 - PT Practice in Acute Care SettingSM199021No ratings yet

- Current Perspectives: Research in Clinical Reasoning: Past History and Current TrendsDocument10 pagesCurrent Perspectives: Research in Clinical Reasoning: Past History and Current TrendsPablo IgnacioNo ratings yet

- 18 Hofmann & Hayes (In Press) The Future of Intervention Science - Process Based TherapyDocument41 pages18 Hofmann & Hayes (In Press) The Future of Intervention Science - Process Based TherapyCharles JacksonNo ratings yet

- Assignment Sheet Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesAssignment Sheet Literature ReviewMegan GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Shubham Gupta CVDocument2 pagesShubham Gupta CVPalash Ravi SrivastavaNo ratings yet

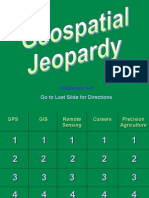

- Geospatial JeopardyDocument54 pagesGeospatial JeopardyrunnealsNo ratings yet

- Heidegger, Martin - On The Way To Language (Harper & Row, 1982) PDFDocument209 pagesHeidegger, Martin - On The Way To Language (Harper & Row, 1982) PDFammar RangoonwalaNo ratings yet

- Kohlbergs Moral DevelopmentDocument31 pagesKohlbergs Moral DevelopmentNiket RaikangorNo ratings yet

- Form - A5 - Student - REVISED PS 09012018 PDFDocument3 pagesForm - A5 - Student - REVISED PS 09012018 PDFLuis Daniel Córdoba AndradeNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development: Process, Models and FoundationsDocument49 pagesCurriculum Development: Process, Models and FoundationsJhay Phee LlorenteNo ratings yet

- The 4 Sections and The 14 Principles of The Toyota WayDocument6 pagesThe 4 Sections and The 14 Principles of The Toyota WayJessica LaguatanNo ratings yet

- Lotf Argument EssayDocument4 pagesLotf Argument Essayapi-332982124No ratings yet

- Law and Poverty - The Legal System and PovertyDocument316 pagesLaw and Poverty - The Legal System and PovertyjitendraNo ratings yet

- Organisational Factors Affecting Employee Satisfaction in The Event IndustryDocument7 pagesOrganisational Factors Affecting Employee Satisfaction in The Event IndustryRitesh shresthaNo ratings yet

- BSA 4C 1 Factors Influenced The Decision of First Year Students of St. Vincent CollegeDocument44 pagesBSA 4C 1 Factors Influenced The Decision of First Year Students of St. Vincent CollegeVensen FuentesNo ratings yet

- Tarlac Agricultural University: Certificate of RegistrationDocument1 pageTarlac Agricultural University: Certificate of RegistrationMarian Kristina SabadoNo ratings yet

- Business Law SyllabusDocument11 pagesBusiness Law SyllabusTriệu Vy DươngNo ratings yet

- When Experience Turns Into NarrativeDocument87 pagesWhen Experience Turns Into NarrativeJudith SudholterNo ratings yet

- 21 Degrees SagittariusDocument11 pages21 Degrees Sagittariusstrength17No ratings yet

- Nexus Network Journal 2Document215 pagesNexus Network Journal 2Jelena MandićNo ratings yet

- EGCE 406 Bridge DesignDocument2 pagesEGCE 406 Bridge DesignNicole CollinsNo ratings yet

- Faculty Profile: 1. Work ExperienceDocument4 pagesFaculty Profile: 1. Work ExperienceMohana UMNo ratings yet

- Math 314 - LessonDocument17 pagesMath 314 - LessonNnahs Varcas-CasasNo ratings yet

- PHD Studentship - Predictive Modelling of Small Crack Formation in Superalloys at Cranfield UniversityDocument2 pagesPHD Studentship - Predictive Modelling of Small Crack Formation in Superalloys at Cranfield UniversityOzden IsbilirNo ratings yet

- 30 S. 2017Document7 pages30 S. 2017MaryroseNo ratings yet

- Apology Letter WorksheetDocument1 pageApology Letter WorksheetViral ShahNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument20 pagesSimone de BeauvoirPrayogi AdiNo ratings yet

- The Ideology of PakistanDocument10 pagesThe Ideology of PakistanRaffay Malik MohsinNo ratings yet

- Celta Lesson Plan TP 3Document5 pagesCelta Lesson Plan TP 3mastro100100% (2)

- 2023 2024 Action Plan in ENGLISHDocument2 pages2023 2024 Action Plan in ENGLISHSa RahNo ratings yet

- SR - No Full Name Standard Seat Number Exam Time Medium SCH Code School NameDocument456 pagesSR - No Full Name Standard Seat Number Exam Time Medium SCH Code School NameBharat VyasNo ratings yet

- Barangay Ambassador: Republic of The Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of TublayDocument3 pagesBarangay Ambassador: Republic of The Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of TublayKathlyn Ablaza100% (1)

- Lesson 3-Cuentos de HadasDocument3 pagesLesson 3-Cuentos de Hadasapi-382813061No ratings yet