Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lilly Commission 2022 0110 Post Trial Reply Brief

Uploaded by

Joe CookseyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lilly Commission 2022 0110 Post Trial Reply Brief

Uploaded by

Joe CookseyCopyright:

Available Formats

FILED

SCR 21-0003

1/10/2022 5:12 PM

tex-60682233

SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS

BLAKE A. HAWTHORNE, CLERK

DOCKET NO. SCR 21-0003

IN RE: § BEFORE THE

§

INQUIRY CONCERNING § SPECIAL COURT OF REVIEW

§

HON. PAUL D. LILLY § APPOINTED BY THE

§

CJC Nos. 19-1767 & 19-1878 § SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS

THE COMMISSION’S POST-SUBMISSION REPLY BRIEF

TO THE HONORABLE MEMBERS OF THE SPECIAL COURT OF REVIEW:

The State Commission on Judicial Conduct (“Commission”) files its Post-Submission

Reply Brief in reply to Judge Paul Lilly’s Post-Hearing Submission Brief filed on December

23, 2021, and in support of the Commission’s allegations against the Honorable Paul D. Lilly

as detailed in its Charging Document filed on August 5, 2021. Because the arguments made in

Judge Paul Lilly’s Post-Hearing Submission Brief are without merit, the Commission, once

again, respectfully requests that the Special Court of Review: (1) impose, at a minimum, a

Public Admonition and Order of Additional Education against Judge Lilly for violations

committed in CJC No. 19-1767; and (2) impose, at a minimum, a Public Admonition and

Order of Additional Education against Judge Lilly for violations committed in CJC No. 19-

1878.

Initially, it should be noted that the bulk of what Judge Lilly’s presents as the facts of

the case – largely comprised from Judge Lilly’s testimony at his hearing before the

Commission 1 – is less a matter of undisputable fact and more a matter of credibility,

1

See Judge Paul Lilly’s Post-Hearing Brief, pp. 6-9 (entitled pp. 1-4).

Copy from re:SearchTX

particularly the credibility of Judge Lilly. This is so regardless of whether the Commission

offered any evidence specifically contradicting any or all of Judge Lilly’s testimony at the final

hearing on the merits. The Commission’s decision to not offer evidence attempting to refute

any and every piece of testimony previously provided by Judge Lilly regarding what are

otherwise immaterial facts should not be conflated with the notion that Judge Lilly’s credibility

is therefore somehow enhanced. Judge Lilly’s credibility or lack thereof is a matter for the fact

finder, this Special Court of Review, to determine. That being said, Judge Lilly’s credibility, for

reasons previously established in the Commission’s Post-Submission Brief is, at this point,

highly questionable. 2 Further, the Special Court of Review is free to read into Judge Lilly’s

unwillingness to testify on his own behalf whatever it wishes, including drawing an inference

that Judge Lilly was fully aware he would be unable to resolve the inconsistencies in his

previous statements upon cross-examination and, therefore, would appear less than credible.

I. CJC NO. 19-1767

A. EVIDENCE OF SPECIFIC RELATIONSHIPS OR SPECIFIC INSTANCES OF

BEHAVIOR IS NOT REQUIRED TO PROVE VIOLATIONS OF RELEVANT

ETHICAL STANDARDS

In his argument, Judge Lilly once again attempts to make the standard set by the

relevant ethical provisions a subjective one when he argues that the Commission has failed to

prove specific instances where a relationship of Judge Lilly’s influenced his judicial conduct. 3

Judge Lilly reinforces this notion when he states that “Canon 2B is focused on third parties

2

See The Commission’s Post-Submission Brief, notes 39-42 et. seq. (regarding Judge Lilly having denied multiple

times under oath at his hearing before the Commission that he set the bond on defendant Adam Ben Carter’s motion

to revoke then later acknowledging, at the final hearing on the merits, that he did in fact set the bond and failed to

consider required statutory factors when doing so), note 54 et. seq. (regarding Judge Lilly’s own witness, Carter,

directly contradicting, at the final hearing on the merits, Judge Lilly’s previous testimony at his hearing before the

Commission that he called Carter because Carter did not yet have an attorney at the time).

3

See Judge Paul Lilly’s Post-Hearing Brief, pp. 10-23 (entitled pp. 5-18).

Copy from re:SearchTX

and a judge’s relationship with them.” 4 Per Judge Lilly’s rationale, it is not enough for the

Commission to prove that Judge Lilly maintains the full authority of both a commissioned

peace officer and a presiding Constitutional County Court judge and in fact performs services

as both a peace officer and a judge. 5 According to Judge Lilly, in order to satisfy the standard

set by the relevant ethical standards, the Commission must prove a specific relationship of

influence, a specific act of bias, or that each and every act of service as a peace officer

performed by Judge Lilly proven by the Commission to have taken place must also have been

accompanied by a concomitant showing of bias, influence, or partiality from the Commission. 6

Once again, however, Judge Lilly attempts to misdirect. The focus of Canon 2B is not

about “third parties and a judge’s relationship with them” but, instead, something much

broader. The focus of Canon 2B, like the focus of Canon 4A(1) and Article V, Section 1-a(6)A

of the Texas Constitution, is about the impressions created in the minds of members of the

public – whether in individual cases, as was the case with the complainant in this matter, or in

general – and whether such impressions include perceptions of bias, influence, partiality, or

discredit upon the judge or the judiciary itself. This is further supported by the fact that Canon

2 itself is explicitly titled “Avoiding Impropriety and the Appearance of Impropriety in All of

the Judge's Activities.” Thus, once again, the standard is plainly an objective one and not

focused subjectively on any one instance of biased behavior or any one specific relationship.

Judge Lilly goes on to provide several cases – some focusing on relevant ethical

provisions and others focusing on when recusal of a judge is appropriate – purportedly

4

Id., at 11 (entitled p. 6).

5

Id., at 10-11 (entitled pp. 5-6).

6

Id.

Copy from re:SearchTX

supporting the argument that only specific instances of bias, influence, or partiality may

establish a violation of relevant ethical standards. 7 Judge Lilly states, “A review of recent of

cases where the Commission has found a violation on [sic] of Canon 4A(1) reveals that the

Commission itself generally requires specific actions or statements in a specific context in

order to ‘cast reasonable doubt’ on a judge’s capacity to act impartially.” 8

However, the cases cited by Judge Lilly are of little to no relevance as they either are in

no way factually similar, do not focus on interpretation of the relevant ethical standards,

address appellate issues which invoke an entirely different burden of persuasion, or involve

matters not at issue in the present case, such as the question of when recusal is appropriate.

More importantly, there is no indication within the holding or dicta of these cases nor within

the language of the relevant ethical provisions themselves that specific instances of conduct

or specific relationships must be a source of bias, influence, or partiality from a judge. The

relevant provisions merely prohibit any conduct which might create the impression that a judge

is subject to bias, influence, or partiality, or which might discredit the judiciary itself, whether

such conduct manifests with specific behaviors or generally through affiliations and

appearances. In other words, just because the cases which Judge Lilly cites happen to involve

specific instances of conduct in no way establishes that specific instances of behavior are

required to constitute violations of relevant ethical standards. Rather, under the language of

the relevant ethical provisions, mere affiliations can constitute violations of relevant ethical

standards since certain affiliations can create the impression of bias, influence, or partiality on

7

Id., at 11-14 (entitled pp. 6-9).

8

Id., at 14 (entitled p. 9).

Copy from re:SearchTX

the part of the judge or cast public discredit upon the judiciary itself. Yet, per Judge Lilly’s

rationale, a judge who was, for example, discovered to be a member of the Ku Klux Klan

would be justified in claiming that his membership alone would be insufficient to establish

that his non-judicial conduct created impressions of bias, influence, or partiality or otherwise

cast discredit upon the judiciary itself, and that only specific instances of racist behavior would

be sufficient to prove violations of relevant ethical provisions.

Judge Lilly then closes his argument by stating that the Commission’s position is a

“slippery slope” as the Commission’s rationale could be applied to judges who are former

police officers, prosecutors, or criminal defense attorneys. 9 Judge Lilly’s “slippery slope”

argument would make for an otherwise salient point if it weren’t for the obvious: there is a

stark contrast between former affiliations one has foregone for the sake of some other cause

and current affiliations one refuses to give up despite a prevailing cause. The Commission’s

position – while not enforcing upon but, instead, grounded within underlying principles

comprising the Separation of Powers Doctrine – can largely be summarized by the old adage

that a person cannot serve two masters. It is the Commission’s position that in attempting to

do so, a judge breaches ethical standards. Accordingly, such position is directly contradictory

to any implication by Judge Lilly that the Commission intends to apply its interpretation

towards those who have given up one master for another. This is not a case of Judge Lilly

being sanctioned by the Commission for being a former police officer while presiding as a

judge, this is a case of Judge Lilly being sanctioned for currently serving as a peace officer while

also presiding as a judge. Simply put, the “slippery slope” scenario which Judge Lilly posits

9

Id., at 22 (entitled p. 17).

Copy from re:SearchTX

does not reflect the facts of this case and, therefore, is not relevant.

B. JUDGE LILLY’S FOCUS ON PS-2000-1 IS MISPLACED

Similar to his Pre-Trial Submission Memorandum, Judge Lilly once again focuses

heavily on allegations that the Commission treats and relies upon PS-2000-1 (Commission’s

Ex. 1) as legal authority rather than the Canons and Texas Constitution themselves. 10

However, as the Commission adequately discussed in its Post-Submission Brief, Judge Lilly’s

focus on the legal authority or lack thereof of PS-2000-1 and the Commission’s reliance upon

such public statement is misplaced. 11 PS-2000-1 does not serve nor has the Commission ever

indicated that it served as any basis for its legal authority in this matter. 12 Instead, PS-2000-1

is merely a notice to the public – without citation to or discussion of supporting legal authority

– of the Commission’s position that concurrent service as both a commissioned peace officer

and presiding judge constitutes violations of relevant ethical provisions. 13 Accordingly, the

Commission does not consider PS-2000-1 “as an interpretation that is entitled to some sort

of Chevron deference” as Judge Lilly states. 14 Rather, the Commission considers its

interpretations of Canons 2B and 4A(1) and Article V, Section 1-a(6)A of the Texas

Constitution as propounded in its Charging Document and subsequent filings to be entitled

to such Chevron deference. 15

C. TCOLE’S PROCESSES AND PROCEDURES ARE NOT RELEVANT

Judge Lilly discusses the processes and procedures for obtaining and maintaining an

10

Id., pp. 15-18 (entitled pp. 10-13).

11

See The Commission’s Post-Submission Brief, Section IIC2.

12

See Commission’s Ex. 1.

13

Id.

14

Judge Paul Lilly’s Post-Hearing Brief, p. 16 (entitled p. 11).

15

See The Commission’s Post-Submission Brief, Section IIC5. See also Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def.

Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 844, 104 S. Ct. 2778, 2782, 81 L. Ed. 2d 694 (1984).

Copy from re:SearchTX

active peace officer’s license as set forth in statutes and rules enforced upon by the Texas

Commission on Law Enforcement (“TCOLE”). 16 Judge Lilly provides this background

because, in his own words, “To become a licensed peace officer is not a simple or easy process

and it is understandable why once obtained, a license holder would not want to allow his

license to go inactive.” 17 In other words, Judge Lilly would like the Special Court of Review

to be aware of how unfair it would be should he have to give up his peace officer license under

statutes and rules enforced by TCOLE if the Commission’s interpretations were adopted.

Even assuming it is the case that Judge Lilly would be forced to let his peace officer

license go inactive in order to ethically serve as a presiding judge, one cannot merely ignore

the fact that Judge Lilly chose to run for an elected office in a different branch of government

than which he already served. Accordingly, any looming injustice from the possibility of having

to let his license go inactive, assuming this is even true, was of his own making and choosing.

In other words, Judge Lilly can hardly be considered the victim in a scenario in which he was

not allowed to have his cake and eat it too.

More importantly, however, as sympathetic a plight Judge Lilly’s may or may not be,

the predominant fact of the matter is that TCOLE’s statutes and rules and how they interpret

such have no bearing as to the Commission’s interpretations of its own statutes and rules. The

injustices which may or may not exist within the processes for maintaining an active peace

officer’s license are irrelevant to a determination as to whether Judge Lilly’s dual service creates

impressions of bias, influence, or partiality on his part or otherwise casts public discredit upon

16

See Judge Paul Lilly’s Post-Hearing Brief, pp. 18-19 (entitled pp. 13-14).

17

Id., at 18 (entitled p. 13).

Copy from re:SearchTX

the judiciary itself.

D. ATTORNEY GENERAL LETTER OPINION NO. 92-35 AND THE

EMOLUMENTS CLAUSE ARE NOT RELEVANT

Judge Lilly goes on to argue that there is no Texas statute or regulation prohibiting dual

service, cites to an attorney general opinion from 1992 – Attorney General Letter Opinion

No. 92-35 – opining that a justice of the peace was not prohibited by the Emoluments Clause

or the doctrine of common-law incompatibility from also serving as an unpaid deputy sheriff

or deputy constable in a different county, and provides a detailed analysis of the Emoluments

Clause itself and why it does not apply. 18 However, the Commission has not disputed that the

Emoluments Clause does not necessarily prohibit dual service in all instances. As Judge Lilly

points out, the Emoluments Clause is inapplicable on its face and, therefore, the Commission

has never claimed such provision has any applicability to the present matter. Likewise, the

Commission does not dispute that Attorney General Letter Opinion No. 92-35 suggests that

dual service is not necessarily legally prohibited in all instances. However, such opinion was

issued in context to a justice of the peace and, therefore, is factually distinguishable from this

matter. Further, such opinion provides no interpretation whatsoever of Canons 2B and 4A(1)

and Article V, Section 1-a(6)A of the Texas Constitution, but, instead, focuses on the

Emoluments clause and the doctrine of common-law compatibility. Therefore, it too is

irrelevant.

More importantly, it matters not that the Emoluments Clause and Attorney General

Letter Opinion No. 92-35 suggest that dual service does not necessarily violate legal provisions

18

Id., at 20-21 (entitled 15-16). See also Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. No. LO-92-35 (1992); Article XVI, Section 40 of the

Texas Constitution (Emoluments Clause).

Copy from re:SearchTX

because the commission has not alleged that Judge Lilly’s conduct constitutes legal violations.

In fact, the Commission has not even alleged that Judge Lilly’s dual service in this specific case

constitutes a direct violation of the Separation of Powers Doctrine itself. None of this is

relevant, however, because as the Commission noted in PS-2000-1, “an act that is legal is not

necessarily an act that is ethical.” 19

The Commission’s legislative mandate is to enforce relevant ethical standards, and only

the Commission has the authority to enforce upon the relevant ethical standards (or, by

extension, Special Courts of Review such as this). Under such authority, the Commission

applies interpretations with intent to enforce the plain meaning of the ethical standards set

forth in the Texas Constitution and/or the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct. In this particular

case, it is the Commission’s interpretation that Judge Lilly’s dual service conveyed the

impression of bias, influence, or partiality on his part or otherwise cast public discredit upon

the judiciary itself. Its interpretation is based on the same principles as the Separation of

Powers Doctrine, but such doctrine is not the vehicle or authority upon which the

Commission enforces its interpretation, nor is PS-2000-1, despite Judge Lilly’s claims to the

contrary. Instead, such vehicle or authorities are those relevant ethical provisions the

Commission as invoked within its Charging Document, specifically Canons 2B and 4A(1) and

Article V, Section 1-a(6)A of the Texas Constitution. Thus, the Commission is both acting

upon its legislatively granted authority and enforcing upon relevant ethical standards with an

interpretation that is both reasonable and not in conflict with the plain language of such

provisions, grounded in the principles of the Separation of Powers Doctrine as it is.

19

Commission’s Ex. 1.

Copy from re:SearchTX

Further, in regard to the Commission’s interpretation of these provisions, the Office

of the Attorney General itself cited to PS-2000-1 in Attorney General Opinion No. GA-0348

and acknowledged that “the question as to whether, under other judicial canons, a municipal

judge holding the position of county commissioner would ‘undermine[ ] the public’s

confidence in an impartial and independent judiciary’ is a question we must leave to the State

Commission on Judicial Conduct.” 20 Thus, the Office of the Attorney General would also

seem to agree that the Commission’s interpretations of the relevant ethical provisions are

indeed owed Chevron deference. 21 Such being the case, unless the Commission’s interpretations

are patently unreasonable and in conflict with the plain language of the statute, they must be

deferred to. 22 Accordingly, this Court should defer to the Commission’s interpretations and

impose, at a minimum, the sanction of a Public Admonition and Order for Additional

Education against Judge Lilly for violations committed in CJC No. 19-1767.

II. CJC NO. 19-1878

A. FAILURE TO CONSIDER REQUIRED STATUTORY FACTORS FOR SETTING

BAIL

Judge Lilly has acknowledged that this violation occurred. 23

B. E X P ARTE COMMUNICATIONS

Judge Lilly maintains that his communications with defendant Adam Ben Carter

20

Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. No. GA-0348 (2005) (quoting and citing to PS-2000-1).

21

See supra note 15.

22

Thompson v. Tex. Dep’t of Licensing & Reg., 455 S.W.3d 569, 571 (Tex. 2014). See also Red Lion Broad. Co. v.

F.C.C., 395 U.S. 367, 380-86, 89 S. Ct. 1794, 1801-1804, 23 L. Ed. 2d 371 (1969) (providing that construction of

statute by a state agency should be followed unless there are compelling indications that it is wrong, especially when

Congress has refused to alter administrative construction); Gladstone Realtors v. Vill. of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 107,

99 S. Ct. 1601, 1612, 60 L. Ed. 2d 66 (1979) (“ . . . the agency’s interpretation of the statute ordinarily commands

considerable deference.”).

23

Judge Paul Lilly’s Post-Hearing Brief, p. 23 (entitled p. 18) (“As to the charge that Judge Lilly did not properly

consider the statutory factors in setting bail, Judge Lilly concedes that he erred in that. He is willing to accept the

decision of the Court as to what sanction, if any, is proper and appropriate for this mistake.”)

10

Copy from re:SearchTX

(“Carter”) did not constitute impermissible ex parte communications because such did not

concern “the merits of a pending or impending judicial proceeding.” 24 In his Post-Hearing

Brief, Judge Lilly states the following:

“In this case, Judge Lilly had a communication with Adam Carter but it was

not a prohibited ex parte communication. Judge Lilly was instead responding

promptly to a 30 day old request from Carter to let him know he was not being

ignored. He contacted the jail to ask about Carter’s status, and during that call

spoke to Carter to let him know he was being appointed an attorney, his case

was being set for a hearing in the next few days and he would be brought over

to Brown County for that purpose. Lilly did not discuss the merits of the case

or any substance of a contested matter with Carter.” 25

Judge Lilly provides an almost complete summary of the relevant facts within this one

paragraph but conveniently leaves out a few key topics of discussion between Carter and Judge

Lilly, topics which have already been stipulated to in the Agreed Stipulations. 26 Specifically,

Judge Lilly leaves out the fact that he directly asked Carter if, as Carter had stated in his letter,

he “truly wanted to plead true and accept time served” if he were to be brought back to Brown

County for a motion to revoke hearing. Based on his own statement, Judge Lilly essentially

wanted to preview over the phone how Carter intended to plead at the hearing. 27 Simply put,

communications between a judge and a party do not get more meritorious than discussing

how that party intends to plead at a hearing. Such being the case, Judge Lilly’s communications

with Carter were undoubtedly ex parte and impermissible under the relevant ethical provisions.

Since Judge Lilly has acknowledged that he failed to consider required statutory factors

24

Id., at 23-24 (entitled pp. 18-19).

25

Id., at 24 (entitled p. 19).

26

See Agreed Stipulations, Stipulation No. 10 (“While the motion to revoke remained pending, Judge Lilly, in

response to a letter from Carter requesting to plead true to the motion to revoke for time served, called Carter directly

in the Runnels County Jail to confirm these were his intentions. Judge Lilly also spoke to a Runnels County jailer

about Carter’s conduct in jail.”).

27

Id.; see also The Commission’s Post-Submission Brief, notes 48-53.

11

Copy from re:SearchTX

for setting bail on Carter’s motion to revoke, and since Judge Lilly undeniably engaged in

impermissible ex parte communications with Carter, this Court should impose, at a minimum,

the sanction of a Public Admonition and Order for Additional Education against Judge Lilly

for violations committed in CJC No. 19-1878.

III. CONCLUSION AND PRAYER

The Commission respectfully request this Honorable Special Court of Review to (1)

affirm the Commission’s decision; (2) impose, at a minimum, the sanction of a Public

Admonition and Order for Additional Education against Judge Lilly for violations committed

in CJC No. 19-1767; and (3) impose, at a minimum, the sanction of a Public Admonition and

Order for Additional Education against Judge Lilly for violations committed in CJC No. 19-

1878.

Dated: January 10, 2022

Respectfully submitted,

KEN PAXTON

Attorney General of Texas

BRENT WEBSTER

First Assistant Attorney General

RYAN L. BANGERT

Deputy First Assistant Attorney General

SHAWN E. COWLES

Deputy Attorney General for Civil Litigation

ELIZABETH BROWN FORE

Chief, Administrative Law Division

12

Copy from re:SearchTX

/s/ Glen Imes

Glen Imes

State Bar No. 24084316

Assistant Attorney General

Ted A. Ross

State Bar No. 24050363

Assistant Attorney General

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TEXAS

ADMINISTRATIVE LAW DIVISION

P. O. Box 12548, Capitol Station (MC-018)

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

Telephone: (512) 936-1838

Facsimile: (512) 320-0167

Glen.Imes@oag.texas.gov

Ted.Ross@oag.texas.gov

ATTORNEY FOR THE STATE COMMISSION ON

JUDICIAL CONDUCT

13

Copy from re:SearchTX

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a true and correct copy of the above and forgoing document

has been served by electronic mail on the 10th day of January 2022, on the following:

Jon Mark Hogg

State Bar No 00784286

JACKSON WALKER LLP

136 W. Twohig Ave., Suite B

San Angelo, Texas 76903

Telephone: (325) 481-2560

Facsimile: (325) 481-2585

jmhogg@jw.com

ATTORNEY FOR JUDGE PAUL LILLY

/s/ Glen Imes

Assistant Attorney General

14

Copy from re:SearchTX

Automated Certificate of eService

This automated certificate of service was created by the efiling system.

The filer served this document via email generated by the efiling system

on the date and to the persons listed below:

Jessica Yvarra on behalf of Glen Imes

Bar No. 24084316

jessica.yvarra@oag.texas.gov

Envelope ID: 60682233

Status as of 1/10/2022 10:14 PM CST

Associated Case Party: State Commission on Judicial Conduct

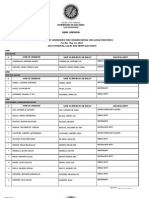

Name BarNumber Email TimestampSubmitted Status

Jeff Lutz jeff.lutz@oag.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Ted Ross ted.ross@oag.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Jessica Yvarra jessica.yvarra@oag.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Jacqueline Habersham jacqueline.habersham@scjc.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Glen imes glen.imes@oag.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Michael GGraham Michael.Graham@scjc.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Phil Robertson Phil.Robertson@scjc.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Zindia Thomas Zindia.Thomas@scjc.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Katherine Cheng Katherine.Cheng@scjc.texas.gov 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Associated Case Party: Hon. Paul Lilly

Name BarNumber Email TimestampSubmitted Status

Carey Edwards cledwards@jw.com 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Jon MarkHogg jmhogg@jw.com 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Celia Morales cmorales@jw.com 1/10/2022 5:12:38 PM SENT

Copy from re:SearchTX

You might also like

- Commission V Lilly Post Trial BriefDocument30 pagesCommission V Lilly Post Trial BriefJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Motion To Dismiss FacebookDocument4 pagesRuth Motion To Dismiss FacebookJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Lilly Application To TarletonDocument12 pagesLilly Application To TarletonJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Judge Lilly Facebook Messages Dirty Talk With SupporterDocument157 pagesJudge Lilly Facebook Messages Dirty Talk With SupporterJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Lilly's Lawyer Demand LetterDocument5 pagesLilly's Lawyer Demand LetterJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- RE Ruth Arrest Body Cam/In Car Video Ruling Or202134308Document4 pagesRE Ruth Arrest Body Cam/In Car Video Ruling Or202134308Joe CookseyNo ratings yet

- 2021-08-26 Letter To Attorney General Requesting Opinion - Cooksey - RedactedDocument4 pages2021-08-26 Letter To Attorney General Requesting Opinion - Cooksey - RedactedJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- State v. Ruth 8-31-21Document21 pagesState v. Ruth 8-31-21Joe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Lilly Post Trial Brief in Commission v. LillyDocument25 pagesLilly Post Trial Brief in Commission v. LillyJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Request For Opinion-Final-SignedDocument7 pagesRequest For Opinion-Final-SignedJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Lilly Transcribed Testimony Before CommissionDocument33 pagesLilly Transcribed Testimony Before CommissionJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Judge Lilly - Knickerbocker Eviction Trial TranscriptDocument15 pagesJudge Lilly - Knickerbocker Eviction Trial TranscriptJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth DisclosuresDocument12 pagesRuth DisclosuresJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Claims He's Broke... Needs A Court Appointed LawyerDocument6 pagesRuth Claims He's Broke... Needs A Court Appointed LawyerJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Peggy Joyce Ruth Deposition 2014Document91 pagesPeggy Joyce Ruth Deposition 2014Joe CookseyNo ratings yet

- ExhibitsDocument673 pagesExhibitsJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Motion For Stay 1 29 2021Document10 pagesRuth Motion For Stay 1 29 2021Joe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Response To Trial Date SettingDocument4 pagesRuth Response To Trial Date SettingJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Application For Writ of Habeas Corpus - BarnumDocument85 pagesApplication For Writ of Habeas Corpus - BarnumJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- ExhibitsDocument673 pagesExhibitsJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Vs Collazo Eastland AppealDocument12 pagesRuth Vs Collazo Eastland AppealJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Joint Motion To Continue SignedDocument4 pagesRuth Joint Motion To Continue SignedJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Application For Writ of Habeas Corpus - BarnumDocument85 pagesApplication For Writ of Habeas Corpus - BarnumJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- John Davis Remarks To Brown County Commissioners CourtDocument3 pagesJohn Davis Remarks To Brown County Commissioners CourtJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Sues Massey and WestDocument36 pagesRuth Sues Massey and WestJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Lilly PSR 2020Document11 pagesLilly PSR 2020Joe CookseyNo ratings yet

- ExhibitsDocument673 pagesExhibitsJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- Ruth Stewart Title Answer and Motion To TransferDocument8 pagesRuth Stewart Title Answer and Motion To TransferJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- 2nd Amended Order Appointing Special ProsecutorDocument19 pages2nd Amended Order Appointing Special ProsecutorJoe CookseyNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Gunslinger Sheet v2Document3 pagesGunslinger Sheet v2Dmread99No ratings yet

- Valenzona vs Fair Shipping Corporation ruling on permanent disability benefits and attorney feesDocument2 pagesValenzona vs Fair Shipping Corporation ruling on permanent disability benefits and attorney feesMigoy DANo ratings yet

- Imm5645e PDFDocument2 pagesImm5645e PDFhawdang nureeNo ratings yet

- 16 - Lazatin v. Hon. Campos, JR., Nora L. de LeonDocument2 pages16 - Lazatin v. Hon. Campos, JR., Nora L. de LeonCha100% (1)

- Globe Magazine Article Kennedy 1 PDFDocument1 pageGlobe Magazine Article Kennedy 1 PDFcrimefileNo ratings yet

- UFC Fit and Tapout XT Hybrid Workout ScheduleDocument2 pagesUFC Fit and Tapout XT Hybrid Workout ScheduleDaniel Diaz DediasiNo ratings yet

- India's Strategic Interests in Western Indian Ocean Maritime SecurityDocument59 pagesIndia's Strategic Interests in Western Indian Ocean Maritime SecurityMariaHameedNo ratings yet

- The Balance Sheet of Sovietism PDFDocument296 pagesThe Balance Sheet of Sovietism PDFDon_HardonNo ratings yet

- Counselor, Social Worker, Instructor, Case ManagerDocument2 pagesCounselor, Social Worker, Instructor, Case Managerapi-77719339No ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument6 pagesReaction PaperBeverly LaraNo ratings yet

- The Study of Surah Yaseen Lesson 04Document6 pagesThe Study of Surah Yaseen Lesson 04Redbridge Islamic CentreNo ratings yet

- Community Policing Partnerships For Problem Solving 7th Edition Miller Solutions ManualDocument5 pagesCommunity Policing Partnerships For Problem Solving 7th Edition Miller Solutions ManualCassandraGilbertodjrg100% (20)

- A Spiritual Warfare ManualDocument130 pagesA Spiritual Warfare Manualfatima110100% (2)

- G.R. No. 165088Document1 pageG.R. No. 165088Johannes Jude AlabaNo ratings yet

- Giant Eagle Theft IndictmentDocument6 pagesGiant Eagle Theft IndictmentWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- RAAF ACMC AMP School Brochure 2023Document8 pagesRAAF ACMC AMP School Brochure 2023Batza BatsakisNo ratings yet

- Undue InfluenceDocument2 pagesUndue Influenceshakti ranjan mohantyNo ratings yet

- Cyber Crime in Pakistan Research ReportDocument20 pagesCyber Crime in Pakistan Research ReportShafirullah Wazir100% (1)

- Paradise Screwed - More Selected ColumnsDocument424 pagesParadise Screwed - More Selected ColumnsJuanan Nuevo100% (1)

- Shalini Kanse PWDVDocument16 pagesShalini Kanse PWDVindrayaniNo ratings yet

- Donoghue V StevensonDocument32 pagesDonoghue V Stevensonpearlyang_200678590% (1)

- 04 A Ism PDFDocument33 pages04 A Ism PDFnazra3No ratings yet

- KXK World Chess ChampionshipsDocument33 pagesKXK World Chess ChampionshipsWágner Tôrres TôrresNo ratings yet

- J & B Expedite Non-Binding Service Agreement Official 2023 - VMG TRANSPORT LOGISTIC LLC - EncryptedDocument7 pagesJ & B Expedite Non-Binding Service Agreement Official 2023 - VMG TRANSPORT LOGISTIC LLC - EncryptedRana Ali.08No ratings yet

- Book hotels and view terms for redBus ticket from Bhopal to AhmedabadDocument2 pagesBook hotels and view terms for redBus ticket from Bhopal to AhmedabadArpit Vidhya JainNo ratings yet

- Go v. BongolanDocument2 pagesGo v. BongolanKC Barras100% (1)

- Must See MoviesDocument7 pagesMust See Movieskac8p637No ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Aglibot Vs ManalacDocument3 pagesAglibot Vs Manalacrafaelturtle_ninjaNo ratings yet

- USS Liberty: NSA Interview With Eugene Sheck - Staff Officer in K GroupDocument65 pagesUSS Liberty: NSA Interview With Eugene Sheck - Staff Officer in K GroupbizratyNo ratings yet