Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ri H2 Econs P1

Ri H2 Econs P1

Uploaded by

Emil YakunOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ri H2 Econs P1

Ri H2 Econs P1

Uploaded by

Emil YakunCopyright:

Available Formats

RAFFLES INSTITUTION

2018 YEAR 6 PRELIMINARY EXAMINATIONS

Higher 2

ECONOMICS 9757/01

Paper 1 Case Study

28 August 2018

2 hrs 15 minutes

Additional Materials: Answer Paper

READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST

Write your name, index number and civics class on all the work you hand in.

Write in dark blue or black pen on both sides of the paper.

You may use a soft pencil for diagrams, graphs or rough working.

Do not use paper clips, highlighters, glue or correction fluid.

Answer all questions.

The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part

question.

This document consists of 8 printed pages.

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

2

Question 1: Madagascar – The Story of Vanilla

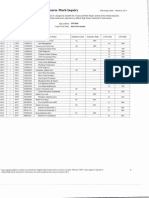

Table 1: Madagascan Exports of Vanilla to the US

Year Price of Vanilla (USD$/kg) Volume (kg) Export Revenue (USD$)

2008 21.5 1,300,000 27,950,000

2009 23 1,150,000 26,450,000

2010 21 - -

Source: www.datamnye.com

Extract 1: Background Knowledge of Vanilla

Vanilla is an essential ingredient used in sweet foods, alcohol, scented perfumes as well as

cosmetics. It is a difficult spice to cultivate and a vanilla vine takes three to four years to mature,

before it could be harvested.

One of the world’s most popular spices, vanilla is also the second most expensive spice in the

world. Today, vanilla accounts for approximately 20% of Madagascan exports, worth $600m

at current prices, and is a significant contributor to Madagascar’s GDP. In fact, Madagascar is

the main exporter of vanilla in the world. Together with the fishing industry, the agriculture

sector, being the largest sector in the Madagascan economy, employs 82% of its labour force

and accounts for 30% of the country’s GDP.

Vanilla farmers, like farmers all over the world, face dramatic fluctuations in the price of the

crops they produce. In the early 1900s, the Madagascar government imposed a fixed price on

vanilla and also intervened in the market through a buyback programme that ensured the

surplus stocks were purchased and kept as inventory. Such intervention ensured price stability

and equity in the distribution of gains from vanilla farming to all. Price fixing succeeded in

keeping the price high and brought about positive results for the farmers for a limited period.

In the end, sustained government intervention meant that the cost of keeping exploding

inventories escalated beyond what could be financed. This led to stocks of inventories being

burnt ultimately, which was an extraordinary waste, given the high unit value of vanilla and the

extreme poverty of the farmers whose output was thus destroyed.

Madagascar’s agriculture performance has also been hindered by problems such as low

productivity and high vulnerability to climatic conditions. A recent cyclone in 2017 destroyed a

number of vanilla plantations and dented supplies from Madagascar. This accelerated an

upswing in prices which had been caused by food manufacturers promising to use real vanilla

rather than synthetic flavourings as well as speculative hoarding by traders in Madagascar.

Vanilla pod producers are now frantically planting more, but it could be several years before

harvesting can take place, allowing prices to subside.

In the meantime, challenges continue to plague the Madagascar economy. The emphasis on

the agriculture sector – dominated by vanilla crops – has resulted in major threats such as

deforestation and soil erosion, and this, together with the lack of investments in new farming

practices and diversification to other crops, had in turn compromised the productivity levels in

farming. In addition, several periods of civil unrest and political uncertainties have disrupted

the economy and made investments scarce.

Source: Adapted from Various Sources

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

3

Extract 2: The History of Madagascar’s Vanilla Industry

Throughout history, the vanilla market had been marred by price instability and low incomes.

In a bid to bring more stability and equity in the distribution of gains from vanilla farming, the

Government of Madagascar created a vanilla stabilization fund where prices were guaranteed,

and a cartel, named the “Vanilla Alliance”, was formed with two neighbouring countries, the

Comores and the Réunion.

The creation of Vanilla Alliance initially brought about positive results, with the world market

expanding rapidly and Madagascar exports swelled. However, the region’s huge market power

in vanilla production and export led to the cartel’s price being significantly higher than the

welfare-maximizing level. The inefficiencies associated with the over-pricing of vanilla

culminated in the flourishment of illegal vanilla trade, while the cartel’s high prices encouraged

the entry of Indonesia into the vanilla market.

Source: http://documents.worldbank.org

Extract 3: The High Price of Madagascar’s Vanilla dependency

Vanilla, like most commodities grown in developing countries, is a fickle crop, which depended

heavily on natural as well as man-made conditions. It is highly labour-intensive and hand-

pollination had to be carried out before the crop could be harvested. The market for vanilla is

also characterised by low entry and exit costs. This had caused the French colonialists to shift

the production of the crop around the world, but only to have production take off when the

method of hand-pollination of the vanilla orchid was devised. Production eventually settled in

Madagascar, where not only was the climate perfect, but it was also “one of the only places

on earth poor enough to make the laborious process of hand pollination worthwhile”.

Today, while over 80 per cent of the world’s fine-quality natural vanilla is exported from

Madagascar, its price volatility has made it difficult for farmers to make a stable living. Prices

over the past five years have whiplashed from US$20 a kilo to a peak of US$600 earlier this

year.

Herein lies the common curse of commodity dependency, whether crude oil, copper, cocoa or

vanilla: heavy dependency on exporting a small number of commodities correlates with

poverty, high mortality rates, low “human development” performance, poor education,

corruption and high levels of income inequality.

But it is Madagascar and its vanilla that tells the depressing story most consistently: its 25

million people share a GDP per capita of barely US$400 – 13 times lower than South Africa,

20 times lower than China and 143 times lower than the US. Seventy-seven per cent of the

population live below the World Bank’s poverty line of US$1.90 a day, with a Human

Development Index in the bottom 30 of countries worldwide.

Against the backdrop of such depressing statistics, it is important to note that when vanilla

prices fell below US$40 five years ago, while India’s farmers simply left the market,

Madagascar’s farmers, were unable to do the same. This is because if they do, they will end

up starving as the economy is not as well-diversified.

So, while times for Madagascar’s 80,000 vanilla farmers are comparatively good at present,

the reality of the commodity curse means that it is only a matter of time before the next crash.

Ever since the development of synthetic vanilla, there has been an inevitable shift away from

the “real thing” to synthetic vanillin. More recently, however, a glimmer of hope has arisen from

a surge among leading vanilla users, which include General Mills, Hershey’s, Kellogg and

Nestle, for “all-natural” ingredients. This being the case, the commitment from these firms must

be regarded as precarious, given the current high price of vanilla.

Source: https://www.scmp.com

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

4

Questions

(a) With reference to Table 1,

(i) Using the data from 2008 and 2009, calculate the PED value of vanilla. [2]

(ii) To what extent can your answer in (ai) allow predictions to be made to total export

revenue as prices decreased between 2009 and 2010? [4]

(b) Using a diagram, identify and explain two factors that will affect the size of the

government’s expenditure in its price fixing programme, in which surplus stocks were

purchased. [6]

(c) Extract 2 mentions that the Government of Madagascar created the “Vanilla Alliance” with

two neighbouring countries.

Discuss the view that having prices that are “significantly higher than the welfare-

maximizing level” outweigh any benefits from the existence of cartels. [8]

(d) Assess whether a country like Madagascar should continue to focus on exporting vanilla

just because it has a comparative advantage in producing vanilla. [10]

[Total: 30 marks]

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

5

Question 2: The post-Brexit1 British economy

Figure 1 Table 2

UK’s BOT EU’s Tariffs on Agriculture Products

2

% of GDP, goods and services

UK's Balance of Trade with EU and non-EU Average EU tariff by product type (%)

1

countries

0 Animal Products 15.7

-1

Dairy Products 35.4

-2

-3 Fruit, vegetables and plant 10.5

-4

Cotton 0.0

-5

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

EU -2.2 -2.1 -2 -1.9 -1.4 -2.5 -3.2 -4 -4.5 Sugars and confectionery 23.6

Non-EU -0.4 -0.9 -0.3 -0.8 -0.2 0 0.3 1 1.1

EU Non-EU Other agricultural products 3.6

Source: House of Commons Website

Source: WTO

World Tariff Profiles 2017

1

Brexit is an abbreviation for "British exit," referring to the UK's decision in a June 23, 2016 referendum

to leave the European Union (EU), an economic union of 28 member states in Europe. The EU is guided

by policies that ensure free movement of labour, goods and services and capital within the union. Post-

Brexit, the UK will no longer be bounded by EU policies.

Extract 4: UK food sector faces enormous challenges post-Brexit

Leaving the EU without a trade deal in place could put up to 97% of British food and drink

exports at risk, according to a House of Lords report that lays bare the UK’s agricultural

industry’s overwhelming reliance on EU’s domestic markets.

As negotiations between the EU and British government appear to take a turn for worse,

concerns are growing that failure to reach an exit deal could leave many industries facing

steep tariff barriers in future – something government ministers hope could be offset by

opportunities in other international export markets.

It is the impact on farmers that is giving policymakers most cause for concern, and the report

warns of a possible quadruple whammy from Brexit as they lose access to EU farm subsidies,

European export markets, access to European workers and protection from cheap imports

from outside the EU.

“Post-Brexit, the UK’s agriculture and food sectors face enormous challenges,” said Robin

Teverson, the chair of the committee. “Life after the EU’s common agricultural policy will not

be easy for the many UK farmers who rely on its financial support.” In other evidence to the

committee, Peter Hardwick, head of exports at the Agriculture and Horticulture Development

Board, a statutory industry body, said: “If we look at our agricultural exports, they are currently

very dependent on trade with the EU and, on average, about 80% of our agricultural exports

go to the EU.”

The government insists it is still confident of striking a comprehensive new free trade

agreement with the EU as well as many new bilateral deals that can replace and expand those

already in place.

Source: The Guardian, 3 May 2017

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

6

Extract 5: A free-trading Britain can prosper after Brexit

As the UK leaves the EU, for the first time in more than 40 years it will be in charge of its own

trade policy. As it begins to negotiate new free trade agreements around the world, it is

imperative that all of the UK’s current and future trading partners, particularly developing

countries, are assured that they will not be worse off as a result of Brexit.

Success in trade and investment is vital for national prosperity. And, contrary to many

predictions, UK’s exports continue to grow year on year after the referendum. Countries such

as South Korea and Japan are now fast-growing markets for UK exports. The tectonic plates

of the world economy are shifting. With an independent trade policy, Britain can put itself in a

strong position to benefit, opening up access to fast-growing markets across the world.

Now is not the time to pull up the drawbridge and retreat into the failure of protectionism. Trade

drives prosperity, which in turn underpins political stability and security. This commitment to

free trade has played a central role in British economic and foreign policy for decades and that

will continue.

Source: Financial Times, 12 November 2017

Extract 6: Britain should brace for weaker economic growth if fewer immigrants come

to its shores after Brexit

The “Brexodus,” as it is called, is being felt particularly acutely in the agriculture industry, which

relies heavily on manual labourers, especially from poor European countries like Romania and

Bulgaria. A government committee said that the UK economy will "very likely" grow more

slowly if immigration from the EU is drastically restricted. Employers were "fearful" over how

their businesses would be affected by tighter restrictions with many planning to relocate to

Asia or other parts of Europe where the operational cost will be lower.

Recruitment of British workers is also difficult because unemployment is already low in farming

regions. Some employers reported that they hire Europeans because those workers have

skills that are scarce in the native workforce, commenting that these European workers are

also more reliable, flexible and willing to do work that Brits find unappealing. However, those

who voted for leave still hold the view that a drop in immigration could mean more jobs for the

people who remained.

The UK food industry is facing a dearth of workers amid the Brexit vote. There are worries that

the production of fresh produce could eventually shift to major competitors in the Netherlands,

Poland and Ireland, or that supermarkets will increasingly turn to imports. Farmers interviewed

said that they were already raising wholesale prices as a result of increased labour costs.

Hospitals are also struggling to hire doctors and nurses. Almost half of doctors were trained

overseas meaning the National Healthcare System (NHS) workforce is particularly vulnerable,

a sign of the system struggling to keep pace with growing demand and an ageing population.

The construction sector last month warned that British infrastructure faced “severe setbacks”

if Britain did not train enough workers to stem a shortfall in labourers from EU countries. The

Brexit vote also gave rise to concerns that minorities and immigrants would be more vulnerable

to hate crimes.

Sources: Adapted from various sources

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

7

Extract 7: Building up the skills we need post-Brexit; a prompt for innovation?

A lot of attention has been paid to the problems of low-skilled workers – the “left-behind” who

voted for Brexit in the first place. A more pressing issue is the fact that for too long a substantial

proportion of UK’s skilled labour has been coming from outside the UK.

The UK has long lagged our competitors on the training of technical skills. Pro-Brexit

campaigners say Britain needs to reduce its reliance on EU workers. “Our sights should be

firmly set on raising the skill level of our own domestic workers, employing domestic whenever

we possibly can and automating,” said Owen Paterson, a member of parliament for the ruling

Conservatives.

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (ADHB) suggested that labour shortages

might be the catalyst for structural and other change: the loss of affordable labour may be the

catalyst that forces the industry to achieve productivity increases, in order to remain

competitive in a global market post-Brexit. Increased capital investment and automation is a

possibility, along with apprenticeship and raising incentives for the economically inactive to

work.

Meanwhile, the Enterprise Minister announced a joint government and industry funding to

improve skills for the NHS’s support workers. The funding will also be used to establish new

‘Excellence Centres’ across England to direct the development of new national e-learning

resources to give more flexible skills training. The new skills training for support workers will

help the NHS become more efficient and create productivity gains. It will also support the

creation of apprentices and trainees, all with a high skills level, to create a more versatile and

robust NHS.

Source: Adapted from various sources

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

8

Questions

(a) Describe the trend in the balance of trade position of the UK with EU countries

between 2007 and 2015 shown in Figure 1. [2]

(b) With the help of a diagram, explain the impact on the total expenditure and

welfare of EU consumers given a tariff on UK’s dairy products. [4]

(c) “Post-Brexit, the UK’s agriculture and foods sectors face enormous challenges.”

(Extract 4 Paragraph 4).

Comment on the likely “challenges” on profits faced by British agriculture and

[6]

foods producers post-Brexit.

(d) Discuss the view that the UK economy has more to lose than gain from a more

restricted immigration flow post-Brexit. [8]

(e) Post-Brexit, the UK policymakers have begun to negotiate new free trade

agreements (Extract 5) with non-EU countries and focus more on supply-side

measures to improve productivity of the British workforce (Extract 7) in light of a

more restricted immigration flow.

Discuss whether the above policies are effective in achieving sustained and

inclusive economic growth in the UK. [10]

[Total: 30 marks]

Copyright Acknowledgements:

Table 1 © www.datamnye.com

Extract 1 © Various Sources: Madagascar Case Study - World Bank Group

Extract 2 © http://documents.worldbank.org: The Elimination of Madagascar’s Vanilla Marketing Board, Ten Years On

Extract 3 © https://www.scmp.com

Figure 1 © House of Commons Website: https://www.parliament.uk/business/commons/

Table 2 © WTO World Tariff Profiles 2017

Extract 4 © The Guardian, 3 May 2017

Extract 5 © Financial Times, 12 November 2017

Extract 6 © Telegraph UK, 20 February 2018; CNN, 27 March 2018; New York Times, 16 December 2017; Independent

UK, 19 December 2017; International Business Times, 3 November 2016

Extract 7 © McKinsey Report 2016; https://ahdb.org.uk/documents/Horizon_Brexit_Analysis_20September2016.pdf;

http://ukandeu.ac.uk/building-up-the-skills-we-need-post-brexit/ ;Reuters, 7 December 2017

© RI 2018 9757/01/Prelim/Y6/18 [Turn over

You might also like

- Research Proposal SampleDocument12 pagesResearch Proposal Samplejojolilimomo75% (4)

- Case Pacari Premium Organic ChocolateDocument14 pagesCase Pacari Premium Organic ChocolateLina Bustillo100% (3)

- Philippine Pineapple Industry PDFDocument10 pagesPhilippine Pineapple Industry PDFJojit Balod50% (2)

- De Beers and NestleDocument4 pagesDe Beers and NestlegagafikNo ratings yet

- Std-Vii-Rise of Small Kingdoms in South India (Notes)Document5 pagesStd-Vii-Rise of Small Kingdoms in South India (Notes)niel100% (2)

- Katherine Johnson Mary Jackson and Dorothy VaughanDocument8 pagesKatherine Johnson Mary Jackson and Dorothy Vaughanapi-326382783No ratings yet

- 1 FT Banana ReportwebDocument20 pages1 FT Banana ReportwebLucrarilicentaNo ratings yet

- The State of The Jamaican Sugar Industry: Production Statistics 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006Document6 pagesThe State of The Jamaican Sugar Industry: Production Statistics 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006Linda zubyNo ratings yet

- Viterra Business PlanDocument15 pagesViterra Business Plannav mixNo ratings yet

- The Sugarcane Industry and The Global Economic CrisisDocument24 pagesThe Sugarcane Industry and The Global Economic CrisisHimanshu MogheNo ratings yet

- Banelino Dominican RepublicDocument20 pagesBanelino Dominican Republicandres alviNo ratings yet

- Cavendish Banana Fairtrade Extended SummaryDocument46 pagesCavendish Banana Fairtrade Extended SummaryEricka Callo LopezNo ratings yet

- Sugar Industry ReportDocument47 pagesSugar Industry ReportTung Bui ThanhNo ratings yet

- Propuesta de Mejora de Competitividad Del Coco Nicaragua2021Document48 pagesPropuesta de Mejora de Competitividad Del Coco Nicaragua2021Catherine CastellonNo ratings yet

- Business Plan Castillo CacaoDocument18 pagesBusiness Plan Castillo CacaobrilloaizaNo ratings yet

- Structured PDF 5 YearsDocument944 pagesStructured PDF 5 YearsDp Brawl StarsNo ratings yet

- Preprints202012 0427 v1Document8 pagesPreprints202012 0427 v1CrownOFFNo ratings yet

- Challenges Encountered by Abaca Product Manufacturers in San Andres, CatanduanesDocument44 pagesChallenges Encountered by Abaca Product Manufacturers in San Andres, CatanduanesPatricia Mae ObiasNo ratings yet

- Perennial Crops: Discuss Research and Development Aspect For Sisal, Coffee, Cashew, Sugar Cane and TeaDocument7 pagesPerennial Crops: Discuss Research and Development Aspect For Sisal, Coffee, Cashew, Sugar Cane and TeaEmmanuel mwansasuNo ratings yet

- Nafta and Imf Case StudiesDocument3 pagesNafta and Imf Case StudiesDevan DaveNo ratings yet

- Vietnam: The Sustainable Coffee ProgramDocument2 pagesVietnam: The Sustainable Coffee Programmoc100% (1)

- Baking Ingredients Market Brief - Manila - Philippines - RP2023-0043Document12 pagesBaking Ingredients Market Brief - Manila - Philippines - RP2023-0043Christian CardiñoNo ratings yet

- 2 Seminario Cutting New Zealand ENGDocument7 pages2 Seminario Cutting New Zealand ENGChristian Alonso Navarro BazalarNo ratings yet

- Agribusiness Sector ProfileDocument9 pagesAgribusiness Sector ProfileRomane DavisNo ratings yet

- Avocado Oil Business PlanDocument13 pagesAvocado Oil Business PlanBusiness consultant100% (2)

- Canada's Blond GoldDocument12 pagesCanada's Blond GoldIvo Van der schansNo ratings yet

- Value Addition Challenges Final PDFDocument16 pagesValue Addition Challenges Final PDFWireNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Assignment BUS 6100Document8 pagesModule 3 Assignment BUS 6100auwal0112No ratings yet

- The Cotton Industry in The Philippines: ' Country StatementDocument8 pagesThe Cotton Industry in The Philippines: ' Country StatementJocelle AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Investing in Rural People in Nicaragua - eDocument4 pagesInvesting in Rural People in Nicaragua - eJohn Alexander CanoNo ratings yet

- Coffee MarketDocument48 pagesCoffee Market08710374100% (2)

- 雀巢放棄KitKats的公平貿易,27,000名農民"錯過了160萬英鎊的付款" 《獨立報》 《獨立報》Document1 page雀巢放棄KitKats的公平貿易,27,000名農民"錯過了160萬英鎊的付款" 《獨立報》 《獨立報》Rainie lawNo ratings yet

- Avocado FarmingDocument5 pagesAvocado FarmingDeus SindaNo ratings yet

- COVID19 WFO Technical Assessment - 005082020Document9 pagesCOVID19 WFO Technical Assessment - 005082020Arslan KhanNo ratings yet

- Sugar Sector Sept 2011Document10 pagesSugar Sector Sept 2011Nehemia Danielson KaayaNo ratings yet

- ConfectionaryDocument29 pagesConfectionaryHabib EjazNo ratings yet

- A Globally Sustainable Supply ChainDocument11 pagesA Globally Sustainable Supply ChainBinod KhatiwadaNo ratings yet

- World Development: Zack Guido, Chris Knudson, Kevon RhineyDocument5 pagesWorld Development: Zack Guido, Chris Knudson, Kevon RhineyJuanes MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Agricultural Practices For Improving Quality of Cocoa Beans: South-West CameroonDocument11 pagesAssessment of Agricultural Practices For Improving Quality of Cocoa Beans: South-West CameroonIJEAB JournalNo ratings yet

- Banana ChainDocument34 pagesBanana ChainGlenda Ortiz MoralesNo ratings yet

- Cocoa Exports of Cameroon Structure and MechanismDocument29 pagesCocoa Exports of Cameroon Structure and MechanismKriss BryteNo ratings yet

- Rice Value Chain Analysis: A Case of Rice Cooperatives Supported by Deutsche Welthunger Hilfe, Southern Province, Rwanda.Document13 pagesRice Value Chain Analysis: A Case of Rice Cooperatives Supported by Deutsche Welthunger Hilfe, Southern Province, Rwanda.Premier PublishersNo ratings yet

- Vinamilk's Supply Chain and The Small Farmers' Involvement: Luc Thi Thu HuongDocument9 pagesVinamilk's Supply Chain and The Small Farmers' Involvement: Luc Thi Thu HuongĐức MinhNo ratings yet

- 2018 Cocoa Barometer Executive SummaryDocument4 pages2018 Cocoa Barometer Executive SummaryWilliam Tagle100% (1)

- Factors of ProductionDocument4 pagesFactors of Productionhilary bassaraghNo ratings yet

- Sustainability Security of The Vanilla Supply Chain Revised Final - May 2023 1Document6 pagesSustainability Security of The Vanilla Supply Chain Revised Final - May 2023 1Vincent ShNo ratings yet

- Chocolate Industry Drives Rainforest Disaster in Ivory CoastDocument3 pagesChocolate Industry Drives Rainforest Disaster in Ivory CoastSimonsNo ratings yet

- Vadilal Industries: The Best Part of EverydayDocument5 pagesVadilal Industries: The Best Part of EverydayMohdmahir Shaikh-DM 20DM124No ratings yet

- Small Farmers and Organic-Banana Production in The Dominican RepublicDocument22 pagesSmall Farmers and Organic-Banana Production in The Dominican RepublicojldmNo ratings yet

- Presentation - Financial Support in Agriculture During PandemicDocument13 pagesPresentation - Financial Support in Agriculture During PandemicKaterina Hadzi NaumovaNo ratings yet

- The Growth and Development of The Horticultural Sector in ZimbabweDocument42 pagesThe Growth and Development of The Horticultural Sector in ZimbabweSolomon Guya0% (1)

- The Wine Industry The Covid 19 PandemicDocument3 pagesThe Wine Industry The Covid 19 PandemicAlison AuNo ratings yet

- Economic Analysis of Cassava Production: Prospects and Challenges in Irepodun Local Government Area, Kwara State, NigeriaDocument5 pagesEconomic Analysis of Cassava Production: Prospects and Challenges in Irepodun Local Government Area, Kwara State, Nigerianicholas ajodoNo ratings yet

- Mugged: Poverty in Our Coffee CupDocument59 pagesMugged: Poverty in Our Coffee CupOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mugged: Poverty in Our Coffee CupDocument59 pagesMugged: Poverty in Our Coffee CupOxfamNo ratings yet

- Ghana's Cocoa Beans Value Addition Best Bet For Africa - The ExchangeDocument6 pagesGhana's Cocoa Beans Value Addition Best Bet For Africa - The ExchangeStevan HaenerNo ratings yet

- Issue of Sugar Industry (Sheraz)Document6 pagesIssue of Sugar Industry (Sheraz)Sheraz ArshadNo ratings yet

- A Study On How Cafe Amadeo DevelopmentDocument18 pagesA Study On How Cafe Amadeo Developmentkeneth john manayagaNo ratings yet

- Impacts of COVID-19 On Canadian Beekeeping: Survey Results and A Profitability AnalysisDocument10 pagesImpacts of COVID-19 On Canadian Beekeeping: Survey Results and A Profitability AnalysisIssa HabeebNo ratings yet

- Agriculture VietnamDocument3 pagesAgriculture VietnamRoy NguyenNo ratings yet

- Income Augmentation Activities of Abaca Farmers in Sabloyon Caramoran, CatanduanesDocument10 pagesIncome Augmentation Activities of Abaca Farmers in Sabloyon Caramoran, Catanduaneschristopher layupanNo ratings yet

- Philippine Sugar 'Crisis' Tests Marcos' Pro-Farms Push - Nikkei AsiaDocument1 pagePhilippine Sugar 'Crisis' Tests Marcos' Pro-Farms Push - Nikkei AsiaElyzah MaeNo ratings yet

- The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2020: Agricultural Markets and Sustainable Development: Global Value Chains, Smallholder Farmers and Digital InnovationsFrom EverandThe State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2020: Agricultural Markets and Sustainable Development: Global Value Chains, Smallholder Farmers and Digital InnovationsNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Water PollutionDocument17 pagesMeaning of Water PollutionAmit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Cubework AgreementDocument11 pagesCubework AgreementHudson GibbsNo ratings yet

- Img 20150510 0001Document2 pagesImg 20150510 0001api-284663984No ratings yet

- Macaw SweaterDocument2 pagesMacaw SweaternyawNo ratings yet

- The Ghost Child: A Carnage Novelette by Simeon Stoychev Smashwords EditionDocument34 pagesThe Ghost Child: A Carnage Novelette by Simeon Stoychev Smashwords EditionYojan ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Self SyllabusDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Self SyllabusNhoj Liryc Taptagap100% (2)

- CAP Medal of ValorDocument4 pagesCAP Medal of ValorCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Instrumentation Lab: Malla Reddy Engineering College (Autonomous) Department of Mechanical EngineeringDocument34 pagesInstrumentation Lab: Malla Reddy Engineering College (Autonomous) Department of Mechanical EngineeringRavi KumarNo ratings yet

- Recognition 2023 ProgrammeDocument16 pagesRecognition 2023 ProgrammeReem MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Proforma Invoice: Bhasin Packard Electronics Pvt. LTDDocument1 pageProforma Invoice: Bhasin Packard Electronics Pvt. LTDbhasin packardNo ratings yet

- MIL L5 NetiquetteDocument61 pagesMIL L5 NetiquetteSherry GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Motor Relearning ProgrammeDocument22 pagesMotor Relearning ProgrammeUzra ShujaatNo ratings yet

- GEK1515 - L1 Introduction IVLE VersionDocument52 pagesGEK1515 - L1 Introduction IVLE VersionYan Ting ZheNo ratings yet

- Please Tell Me How I AmDocument13 pagesPlease Tell Me How I AmNathalia QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Manufacturing ConcernDocument2 pagesAccounting For Manufacturing ConcernAhmed MemonNo ratings yet

- Cabanez v. SolanoDocument3 pagesCabanez v. SolanoMishel EscañoNo ratings yet

- Final PHD Thesis - Abeer AlsalloomDocument374 pagesFinal PHD Thesis - Abeer Alsalloomayunda rizqiNo ratings yet

- Solar Powered DC Fridge Owners ManualDocument20 pagesSolar Powered DC Fridge Owners ManualPawel Vlad LatoNo ratings yet

- Traffic Module 3Document9 pagesTraffic Module 3Marj BaniasNo ratings yet

- Cooking Verbs Vocabulary Missing Letters in Words Esl WorksheetDocument2 pagesCooking Verbs Vocabulary Missing Letters in Words Esl WorksheetMariagabriela ArgüelloNo ratings yet

- Questions & Ans For BHTPA-P6A Course Name: "Professional Digital Content Management"Document53 pagesQuestions & Ans For BHTPA-P6A Course Name: "Professional Digital Content Management"Rasel Ali100% (1)

- Can You Find All The Hidden Words in This Word Search? Words Can Go in The Following DirectionsDocument3 pagesCan You Find All The Hidden Words in This Word Search? Words Can Go in The Following Directionspj501No ratings yet

- Basics! Essentials of Modern C++ Style - Herb Sutter - CppConDocument38 pagesBasics! Essentials of Modern C++ Style - Herb Sutter - CppConARAVIND RNo ratings yet

- Inclination Sensor CorrectionDocument3 pagesInclination Sensor CorrectionFrank SmithNo ratings yet

- Managerial Business Analytics Mgt782 (Finished)Document22 pagesManagerial Business Analytics Mgt782 (Finished)Eryn LisaNo ratings yet

- Data Mining - Exercise 2Document30 pagesData Mining - Exercise 2Kiều Trần Nguyễn DiễmNo ratings yet

- PCP Chassis Frame 2801000 BU02Document6 pagesPCP Chassis Frame 2801000 BU02Võ Trung HiếuNo ratings yet