Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Harvest of Sorrows - Gutierrez Mangansakan II

A Harvest of Sorrows - Gutierrez Mangansakan II

Uploaded by

heart0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views4 pagesA Harvest of Sorrows

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA Harvest of Sorrows

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views4 pagesA Harvest of Sorrows - Gutierrez Mangansakan II

A Harvest of Sorrows - Gutierrez Mangansakan II

Uploaded by

heartA Harvest of Sorrows

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

A Harvest of Sorrows

by Gutierrez Mangansakan II

"It was a girl."

The women are huddled in front of a bamboo pole, their bare feet caked in mud

from last night's downpour, whispering among themselves, when I arrive in the

evacuation center. It is nine o'clock. The sun is already high in the sky.

"Aday. It was a girl."

They mutter, their heads shaking, stares fixed on the ground. They become silent

as soon as the truck stops in front of them." They are here," I hear a familiar voice,

Ayesha’s voice, the social worker whose task is to supervise relief operations in this

remote village. "Come inside," she waves at me. She is standing under an enormous

blue tent, which for the past three weeks has been her home and office.

"We brought several sacks of rice," I point to the truck as I walk towards her.

"I'll ask somebody to bring them in," she tells me." What happened?" I

ask her.

Ayesha tells me the story. There was a woman who gave birth at the crack of dawn.

One of the refugees. The child was premature. Stillborn. Fleeing their village three days

on foot was too much for her. That could have induced the early contraction. Aday. Baba

pan panem.

Ayesha worries that the refugee woman's husband does not know yet. He did not

return to the evacuation center last night. It must be the rain. It poured heavily throughout

the evening. He went back to the village to check their house yesterday morning together

with the other husbands. Harvest is only ten days away. It is here almost the husband

told his wife that he wanted to have money in time for the birth of their child. The rice

field was beginning to turn golden when they heard the droning of the military choppers

two weeks ago. But the husband said the conflict was far from their village. "It will pass

like before," he tried to placate his wife and mother-in-law. And now his family is in an

evacuation center in this unfamiliar village, together with hundred other families, bringing

with them only the barest essentials in their rush to make an escape when bombs started

falling from the sky. His daughter is dead. He still does not know the news.

"You may be hungry by now," Ayesha says as she sets the table. There is grilled

mudfish. I look outside the tent. There are hundreds of people in the back yard. They are

refugees who have fled their homes-like the woman grieving her dead child- taking

shelter in this village since fighting started two weeks ago.

Nobody knows for certain which side started the recent spate of violence. When

the peace negotiation between the government and the Muslim rebels bogged down in

June, it was almost certain that this was going to happen. The agreement would have

paved the way for the creation of a large autonomous region that allows the Muslims

greater freedom to practice their faith, and with it systems that will shape the future that

they long for. But some politicians, mostly scions of settler families from the North, cried

fowl. They claim that they were not consulted about the provisions of the agreement.

After all, they have settled in this part of the country for decades. Their parents came

here in packs, starting in the 1920s when they were offered homesteads to populate the

region by the national government. They, too, have rights. Whatever the Muslims claim,

this is home for them as well.

The agreement violated the Constitution. That is what they argued. They went to

the Supreme Court and asked that the signing of the agreement be stopped. They got

what they wanted. The fighting began. "I'm not really hungry," I tell Ayesha. She offers

me coffee instead. Who can eat when everybody else is hungry? When refugees started

arriving two weeks earlier, she had called me." We need help. There are a hundred

families here. Relief has not arrived."

We met five years ago. She was then a social work intern when fighting broke out.

She was assisting relief operations in my hometown. I was a documentarist eager for a

subject. We became instant friends, and when I got her call, I knew she desperately

needed help.

Today she is assigned to this village fifteen kilometers away from the town

center. You have to travel across rough, dusty limestone road to get here. When it rains,

it becomes the gloppy mud you pray you never get stuck in. It is like swimming in a bowl

of thick oatmeal.

I started calling friends to ask for donations. Money, food, blankets, medicines,

anything. Relying on aid from the social welfare department is frustrating. They refuse

to give food aid to refugees in evacuation centers far-flung villages. “They say the relief

goods will only go to the rebels, ' a friend of mine, a veteran journalist who has been

covering the armed conflict since the 1970s. Charity organizations, the type that big

businesses establish to circumvent tax laws, are the most atrocious kind. They assure

you that help is coming in the next hour or so. You relay the good news to refugees who

depend on your strong connection for their supper, only to find out later that help will not

arrive that day because a TV network is too busy to cover the PR stint. The refugee will

get disappointed. You ask yourself: Will they trust me tomorrow?

And now that a child is dead, maybe people from the network will come. A truck

relief goods, too. TV has a penchant for hyperbole, and a dead child, a victim of war,

even, indirectly, might make it to the six-thirty newscast. The United Nations Secretary-

General Ban Ki-moon said that this war had become a serious humanitarian disaster.

According to a CNN report, the World Food Programme had warned of shortages in food

supply in their efforts in Darfur and other places due to the looming world financial crisis.

It will only take a matter of time before relief supply dries up in their efforts here in

Mindanao, where the Muslim insurgency has been going on for the past forty years.

When I drove to the village an hour earlier I remembered the first time I

encountered the war. It was in the summer of 2000, a very long time ago. I returned to

my hometown to shoot photographs. A few weeks after I arrived, the president declared

war against the Muslim secessionists. The war displaced almost a million people. I took

hundreds of photographs of the refugees, and now I chose not to bring a camera, but

just capture these indelible images in my memory: the forlorn faces of mothers trying to

hush their crying infants, livestock tied to a tree with a leash so short they might die of

strangulation, a heap of belongings here and there, smokes billowing from makeshift

stoves which leave me dumbstruck—what could they be cooking?—when help is yet to

arrive.

I arrived only thirty minutes ago. The sacks of rice that I brought are still stacked

at the house's front porch. These images will stick in my mind for a long time. From time

to time, it will wake me up from a comfortable sleep. These images I will never forget.

Aday. It was a girl. I overhear a woman tell her teenage daughter as they pass the

tent. Soon the entire village will hear the news.

The child is dead. Her father does not know yet. He guards the rice field now heavy

with fruit from birds and looters. Under a mango tree, he thinks of his wife and, in his

mind, a child yet to be born. He remembers the worry on his wife's face when he left her

only yesterday. Yesterday was a long time ago. He consoles himself with a thought. My

child will grow strong and study hard and become a professional and live in the city far

from all this. "From a distance, a chopper cuts the silence. Reality sets in again. "They

have sent for the father," Ayesha announces. "They will bury the child after the noon

prayer." I nod and drink my coffee until I choke on the granules that have settled it the

bottom of the cup.

THE MAN BEHIND

Hailing from the traditional family of Maguindanao, Gutierrez Mangansakan is a

prolific writer, educator, art scholar, and award-winning filmmaker. Spending more than

20 years in the film industry, Mangansakan, or popularly known as Tng Man (

pronounced as teng man) is considered as one of the prominent personalities of the

Regional Cinema Movement in the Philippines. He produced many films that received

international accolades. In 2010, Libunan was a finalist in the Cinemalaya Philippine

Independent Film Festival. It was nominated in the Gawad Urian (Critics Prize) for best

film and was selected as the closing film of the Critics Week section of the prestigious

Venice International Film Festival. This movie centers on a Muslim woman who is forced

to marry a man whom she does not know to obey the long-time tradition of a Muslim

family. Other films that take part in Gutierrez’ body of works include the following:

❖ Cartas de la Soledad (Letters of Solitude) (2011), a story about Rashid Ali,

who studied and worked in Europe for 25 years. He returns to Maguindanao to change

the lives of the Maguindanaoans.

❖ Forbidden Memory (2016)- a film that recounts the killing of 1,500 men from

Malisbong and neighboring villages in Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat in September 1974.

There were 3,000 women and children were rescued when the massacre took place.

❖ The Obscured Histories and Silent Longings of Daguluan's Children

(2012)- the film presents the daily struggle of the people with poverty, while they continue

to preserve their traditions despite the coming of the war.

❖ Daughters of the Three Tailed Banner (2016)- the film shows the dilemma of

the Muslim women in the male-dominated society. As a writer, Gutierrez’ works

contributed to more than two dozen of books in the Philippines and abroad. In 2008, he

was a writer-in-residence in the International Writing Program of the University of Iowa.

He served as a fellow of the 54th University of the Philippines National Writers Workshop

in 2015. In 2018, he was a mentor of the Asia Pacific Screen Lab - Griffith Film School

of the University of Queensland, Australia.

In September 2019, the Office of the President-Film Development Council of the

Philippines honored Gutierrez for his artistry, vision, and contribution to the development

of the Philippine national cinema

You might also like

- Reading A Harvest of SorrowsDocument6 pagesReading A Harvest of SorrowsJohn Carlo deparene75% (4)

- An Earnest ParableDocument2 pagesAn Earnest ParableJulia Paula80% (10)

- Position PaperDocument3 pagesPosition PaperMaria Macel100% (1)

- Third World GeographyDocument2 pagesThird World Geographytin_taw45% (11)

- Dumpit Cristaiza - An Analysis To The Poem "The Haiyan Dead"Document6 pagesDumpit Cristaiza - An Analysis To The Poem "The Haiyan Dead"Cristaiza R. DumpitNo ratings yet

- Of Fish, Flies, Dogs, and WomenDocument11 pagesOf Fish, Flies, Dogs, and WomenMa. Lourdes Carla Ramos50% (2)

- Saint Louis University Laboratory High School - Senior High Cvd19 Act2 - Geological HazardsDocument3 pagesSaint Louis University Laboratory High School - Senior High Cvd19 Act2 - Geological HazardsDave BillonaNo ratings yet

- Gemino AbadDocument5 pagesGemino AbadDaisy Mae Gujol100% (1)

- Of A Promise KeptDocument4 pagesOf A Promise KeptDana Mae ManerwapNo ratings yet

- Guide Questions: by Khaled HosseiniDocument2 pagesGuide Questions: by Khaled HosseiniDoh Dong DrakeNo ratings yet

- 21st Report - Lesson 7 Philippine Literature Turns and TropesDocument13 pages21st Report - Lesson 7 Philippine Literature Turns and TropesDanielV.Quiambao100% (1)

- 21st Century Third World GeographyDocument3 pages21st Century Third World GeographyMae Baltera0% (1)

- Critical Essay PrintDocument4 pagesCritical Essay PrintAce Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Literary, Biographical, Linguistic, and Socio-Cultural ContextsDocument37 pagesLiterary, Biographical, Linguistic, and Socio-Cultural ContextsRaeghan GrymesNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper AljaneDocument2 pagesReaction Paper AljaneJane Rica Riego100% (3)

- Case Study Abt IlocanosDocument3 pagesCase Study Abt Ilocanosquincy100% (1)

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Title: Anto By: Rogelio L. OrdonezDocument4 pages21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Title: Anto By: Rogelio L. OrdonezEdwin Peralta III100% (3)

- English For Academic and Professional PurposesDocument10 pagesEnglish For Academic and Professional Purposesazileinra OhNo ratings yet

- Literary Analysis of A Novel's Excerpt Written by Alex GarlandDocument14 pagesLiterary Analysis of A Novel's Excerpt Written by Alex GarlandLot Villegas89% (9)

- The Filipino LanguageDocument3 pagesThe Filipino LanguageBianca Jane GaayonNo ratings yet

- The Last Days of Magic - Ian Rosales Casocot PDFDocument4 pagesThe Last Days of Magic - Ian Rosales Casocot PDFYsabel Julienne Rae Borgonia100% (1)

- Lesson 3: Testimonio: Testimonio, Which Traces Its Origin To Autobiographical LiteratureDocument1 pageLesson 3: Testimonio: Testimonio, Which Traces Its Origin To Autobiographical LiteratureWendy BustamanteNo ratings yet

- WT4 EappDocument2 pagesWT4 EappXander Christian RaymundoNo ratings yet

- 21st LiteratureDocument5 pages21st LiteratureBenedict OrejasNo ratings yet

- Critique PaperDocument6 pagesCritique PaperMilagros Marilao100% (1)

- Under My Invisible UmbrellaDocument5 pagesUnder My Invisible Umbrellaanon_769788318No ratings yet

- Region: Dion Michael FernandezDocument5 pagesRegion: Dion Michael FernandezAndrei Patrick Dao-ay Borja100% (3)

- An Excerpt From BanyagaDocument6 pagesAn Excerpt From BanyagaTwinkle Mae AuroNo ratings yet

- Worship and ObservancesDocument7 pagesWorship and ObservancesKaeryllMaySaysonNavalesNo ratings yet

- A. Answer The Following Questions.: 1.what Important Decision Did Della Have To Make On That Day Unforgettable Day?Document2 pagesA. Answer The Following Questions.: 1.what Important Decision Did Della Have To Make On That Day Unforgettable Day?Manuel Aldrin PaularNo ratings yet

- FABM Dictionary 1Document32 pagesFABM Dictionary 1Candy TinapayNo ratings yet

- The Lucky PlazaDocument6 pagesThe Lucky Plazajhomalyn100% (1)

- Who Is PepeDocument1 pageWho Is PepeJeprox 007No ratings yet

- The Persona Was Able To Establish Some Similarities and Difference Between Her and The Migrant WorkerDocument2 pagesThe Persona Was Able To Establish Some Similarities and Difference Between Her and The Migrant Workerregail copy centerNo ratings yet

- The Lived Experiences of Male Online SellersDocument24 pagesThe Lived Experiences of Male Online SellersRogiedel MahilomNo ratings yet

- Famous People Region 8 RPHDocument2 pagesFamous People Region 8 RPHBae MaxZNo ratings yet

- Reading Lit Assignment Humss & GasDocument44 pagesReading Lit Assignment Humss & GasGrace Cabiles - LacatanNo ratings yet

- The Boy Named Crow PDFDocument2 pagesThe Boy Named Crow PDFGrishan Lake Delacruz BansingNo ratings yet

- Region 10 Legend The Battle at TagoloanDocument17 pagesRegion 10 Legend The Battle at TagoloanAmeurfina MiNo ratings yet

- OutlineDocument2 pagesOutlineMaria Beatrice0% (2)

- Testimonio ExampleDocument2 pagesTestimonio ExampleReigne CuevasNo ratings yet

- The Academic Performance of Grade 12 ABM Students in Their Accounting SubjectDocument4 pagesThe Academic Performance of Grade 12 ABM Students in Their Accounting SubjectKhriza Joy SalvadorNo ratings yet

- II Individual Activity Spider MapDocument3 pagesII Individual Activity Spider Mapapi-3412752510% (3)

- HITTING BUDAPEST: Marxist CriticsmDocument4 pagesHITTING BUDAPEST: Marxist CriticsmMa Joelle50% (2)

- Review of Related Studies and LiteratureDocument9 pagesReview of Related Studies and LiteratureMaria Yvonne Araneta100% (1)

- WEEK2 - The Boy Named CrowDocument7 pagesWEEK2 - The Boy Named CrowNICK DULINNo ratings yet

- Why We Are ShallowDocument4 pagesWhy We Are ShallowXyza Faye RegaladoNo ratings yet

- Contexts of The 21st Century Philippine National and Reading Approaches in Appreciation of LiteratureDocument1 pageContexts of The 21st Century Philippine National and Reading Approaches in Appreciation of LiteratureRonnieNo ratings yet

- Intertextuality EssayDocument2 pagesIntertextuality EssaySama AlkouniNo ratings yet

- At Merienda - Individual ActivityDocument6 pagesAt Merienda - Individual ActivityMoreno, John Gil F.No ratings yet

- At MeriendaDocument25 pagesAt MeriendaBarbie Coronel20% (5)

- Contemporary Arts Module 2Document16 pagesContemporary Arts Module 2seokjinie paboNo ratings yet

- Replektibong Sanaysay (Kanta)Document2 pagesReplektibong Sanaysay (Kanta)Mico LlanitaNo ratings yet

- Reading A Harvest of SorrowsDocument6 pagesReading A Harvest of SorrowsJohn Carlo depareneNo ratings yet

- Roots Novel CompressedDocument27 pagesRoots Novel Compressednisingizwealbert4No ratings yet

- 11 Logical Fallacies Worksheet AnswersDocument4 pages11 Logical Fallacies Worksheet AnswersXiao NaNo ratings yet

- My BrotherDocument4 pagesMy BrotherXiao NaNo ratings yet

- (LYRICS) 想去海边 (Want to go to beach)Document2 pages(LYRICS) 想去海边 (Want to go to beach)Xiao NaNo ratings yet

- "The Flood" An Excerpt From "Without Seeing The Dawn"Document6 pages"The Flood" An Excerpt From "Without Seeing The Dawn"Xiao NaNo ratings yet

- Sixth Grade Boy Is A HERO!!!: L-6-2-2 - Newspaper StoryDocument2 pagesSixth Grade Boy Is A HERO!!!: L-6-2-2 - Newspaper StoryXiao NaNo ratings yet

- Wedding DanceDocument1 pageWedding DanceXiao NaNo ratings yet

- Script For SatDocument2 pagesScript For SatXiao NaNo ratings yet

- Focused Group Discussion Q&ADocument2 pagesFocused Group Discussion Q&AXiao NaNo ratings yet

- Prejudice: How To Detect Bias in The NewsDocument4 pagesPrejudice: How To Detect Bias in The NewsXiao NaNo ratings yet

- Good Day, Grade 9!: "Believe That You Can and You'Re Halfway There." - Theodore RooseveltDocument25 pagesGood Day, Grade 9!: "Believe That You Can and You'Re Halfway There." - Theodore RooseveltXiao NaNo ratings yet

- The Cleaner by Matshidiso BellaDocument586 pagesThe Cleaner by Matshidiso BellaTHABISILE MBATHANo ratings yet

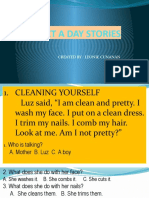

- A TEXT A DAY by LeonyDocument32 pagesA TEXT A DAY by LeonyRose Ann Rodriguez PeñalozaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Flower BouquetDocument2 pagesArtificial Flower BouquetYoshua GaloenkNo ratings yet

- Coordinating ConjunctionsDocument4 pagesCoordinating Conjunctionsleah rualesNo ratings yet

- Wordpool All UnitsDocument7 pagesWordpool All UnitsShanaya HelpsNo ratings yet

- The Manor Andara (Umara)Document10 pagesThe Manor Andara (Umara)ypkvcgcqpzNo ratings yet

- Laporan Data Transaksi MocashDocument80 pagesLaporan Data Transaksi MocashdhitabwNo ratings yet

- Vegetales, Portadores y Emolientes Datos Maestros de Aceites HLBDocument4 pagesVegetales, Portadores y Emolientes Datos Maestros de Aceites HLBHamsa RyuuganNo ratings yet

- Midterm LMDocument9 pagesMidterm LMMay Lane Sudarno PutNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Engineering Comprehensive Board Exam Reviewer Volume II - 1Document29 pagesAgricultural Engineering Comprehensive Board Exam Reviewer Volume II - 1Alfredo CondeNo ratings yet

- Experiment 2: Proteins: ObjectivesDocument6 pagesExperiment 2: Proteins: ObjectivesNolan GrayNo ratings yet

- Idioms & Phrases (CSS 2000-2019)Document3 pagesIdioms & Phrases (CSS 2000-2019)hafiza arishaNo ratings yet

- Transparency in Food Supply Chains A Review of Enabling Technology SolutionsDocument8 pagesTransparency in Food Supply Chains A Review of Enabling Technology SolutionsAnkitNo ratings yet

- Restaurant MenuDocument2 pagesRestaurant MenuarnNo ratings yet

- BPT 1Document3 pagesBPT 1princesbuh320No ratings yet

- Contrast Conjunction2Document7 pagesContrast Conjunction2ASPARAGUS CHANNELNo ratings yet

- Brain Damaging Habits: 1. No BreakfastDocument8 pagesBrain Damaging Habits: 1. No BreakfastSAKTHIVEL A100% (1)

- F2F Elem - UNIT 9B Grammar Note - Comparative AdjectivesDocument5 pagesF2F Elem - UNIT 9B Grammar Note - Comparative AdjectivesTessi AstrianaNo ratings yet

- Market Research For Vegetarian MeatDocument7 pagesMarket Research For Vegetarian MeatNgọc Phạm Nguyễn ThanhNo ratings yet

- Q3 Module5 G10 COOKERYDocument8 pagesQ3 Module5 G10 COOKERYJayzi VicenteNo ratings yet

- Self-Styling, Popular Culture, and The Construction of Global-Local Identity Among Japanese Food Lovers in PurwokertoDocument20 pagesSelf-Styling, Popular Culture, and The Construction of Global-Local Identity Among Japanese Food Lovers in Purwokertodiana triNo ratings yet

- Cookery 3Document8 pagesCookery 3Nheedz Bawa JuhailiNo ratings yet

- Transcripts Set 1Document10 pagesTranscripts Set 1insan biasaNo ratings yet

- Marbled Crayon StonesDocument56 pagesMarbled Crayon StonesGabriel Antonio NájeraNo ratings yet

- YELLOW CORN (Zea Mays)Document11 pagesYELLOW CORN (Zea Mays)Jeric MadroñoNo ratings yet

- Open Sandwiches (Trine Hahnemann)Document187 pagesOpen Sandwiches (Trine Hahnemann)Leyre Tortosa del Olmo100% (1)

- Curing & Smoking of Meat: ANSC 3404Document22 pagesCuring & Smoking of Meat: ANSC 3404sitinurhanizaNo ratings yet

- Analisis Sensori Produk Stik Sukun (Artocarpus Altilis) Dengan Perlakuan Pendahuluan Blanching Dan Perendaman Dalam Larutan Kalsium KloridaDocument6 pagesAnalisis Sensori Produk Stik Sukun (Artocarpus Altilis) Dengan Perlakuan Pendahuluan Blanching Dan Perendaman Dalam Larutan Kalsium KloridaTommy ChandraNo ratings yet

- Milk ProteinsDocument5 pagesMilk ProteinsFadil NurhidayatNo ratings yet

- A Pizza: Yes, He Was HungryDocument2 pagesA Pizza: Yes, He Was HungryDileysi DionicioNo ratings yet