Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scientists Study How A Single Gene Alteration May Have Separated

Uploaded by

RT CrOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Scientists Study How A Single Gene Alteration May Have Separated

Uploaded by

RT CrCopyright:

Available Formats

CURIOUS FEBURARY 2021

Scientists study how a single gene alteration may have separated

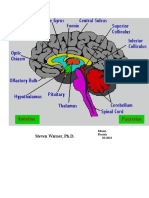

As a professor of pediatrics and cellular and molecular medicine at University of California San Diego School of

Medicine, Alysson R. Muotri, PhD, has long studied how the brain develops and what goes wrong in neurological

disorders. For almost as long, he has also been curious about the evolution of the human brain -; what changed that

makes us so different from preceding Neanderthals and Denisovans, our closest evolutionary relatives, now extinct?

Evolutionary studies rely heavily on two tools -; genetics and fossil analysis -; to explore how a species changes over

time. But neither approach can reveal much about brain development and function because brains do not fossilize,

Muotri said. There is no physical record to study.

So Muotri decided to try stem cells, a tool not often applied in evolutionary reconstructions. Stem cells, the self

renewing precursors of other cell types, can be used to build brain organoids -; "mini brains" in a laboratory dish.

Muotri and colleagues have pioneered the use of stem cells to compare humans to other primates, such as chimpanzees

and bonobos, but until now a comparison with extinct species was not thought possible.

In a study published February 11, 2021 in Science, Muotri's team cataloged the differences between the genomes of

diverse modern human populations and the Neanderthals and Denisovans, who lived during the Pleistocene Epoch,

approximately 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. Mimicking an alteration they found in one gene, the researchers used

stem cells to engineer "Neanderthal-ized" brain organoids.

It's fascinating to see that a single base-pair alteration in human DNA can change how the brain is wired. We

don't know exactly how and when in our evolutionary history that change occurred. But it seems to be significant,

and could help explain some of our modern capabilities in social behavior, language, adaptation, creativity and

use of technology."

Alysson R. Muotri, Study Senior Author, Director, UC San Diego Stem Cell Program and Member, Sanford

Consortium for Regenerative Medicine

The team initially found 61 genes that differed between modern humans and our extinct relatives. One of these altered

genes -; NOVA1 -; caught Muotri's attention because it's a master gene regulator, influencing many other genes during

early brain development. The researchers used CRISPR gene editing to engineer modern human stem cells with the

Neanderthal-like mutation in NOVA1. Then they coaxed the stem cells into forming brain cells and ultimately

Neanderthal-ized brain organoids.

Brain organoids are little clusters of brain cells formed by stem cells, but they aren't exactly brains (for one, they

lack connections to other organ systems, such as blood vessels). Yet organoids are useful models for studying

genetics, disease development and responses to infections and therapeutic drugs. Muotri's team has even optimized

the brain organoid-building process to achieve organized electrical oscillatory waves similar to those produced by

the human brain.

The Neanderthal-ized brain organoids looked very different than modern human brain organoids, even to the

naked eye. They had a distinctly different shape. Peering deeper, the team found that modern and Neanderthal-ized

brain organoids also differ in the way their cells proliferate and how their synapses -; the connections between

neurons -; form. Even the proteins involved in synapses differed. And electrical impulses displayed higher activity

at earlier stages, but didn't synchronize in networks in Neanderthal-ized brain organoids.

According to Muotri, the neural network changes in Neanderthal-ized brain organoids parallel the way newborn non-

human primates acquire new abilities more rapidly than human newborns.

"This study focused on only one gene that differed between modern humans and our extinct relatives. Next we want

to take a look at the other 60 genes, and what happens when each, or a combination of two or more, are altered,”

Muotri said

VIJETHA IAS ACADEMY

ADDRESS: 7/50, II FLOOR, NEAR ROOP VATIKA, SHANKAR ROAD, OLD RAJENDAR NAGAR, NEW DELHI — 110060

HOTLINE: 011- 42473555, 9650852636 , 7678508541 , DATABASE: WWW.VIJETHAIASACADEMY.COM

CURIOUS FEBURARY 2021

"We're looking forward to this new combination of stem cell biology, neuroscience and paleogenomics. The ability

to apply the comparative approach of modern humans to other extinct hominins, such as Neanderthals and

Denisovans, using brain organoids carrying ancestral genetic variants is an entirely new field of study."

To continue this work, Muotri has teamed up with Katerina Semendeferi, professor of anthropology at UC San

Diego and study co-author, to co-direct the new UC San Diego Archealization Center, or ArchC.

"We will merge and integrate this amazing stem cell work with anatomic comparisons from several species and

neurological conditions to create downstream hypotheses about brain function of our extinct relatives,”

Semendeferi said. "This neuro-archealization approach will complement efforts to understand the mind of our

ancestors and close relatives, like the Neanderthals."

VIJETHA IAS ACADEMY

ADDRESS: 7/50, II FLOOR, NEAR ROOP VATIKA, SHANKAR ROAD, OLD RAJENDAR NAGAR, NEW DELHI — 110060

HOTLINE: 011- 42473555, 9650852636 , 7678508541 , DATABASE: WWW.VIJETHAIASACADEMY.COM

CURIOUS FEBURARY 2021

A body burned inside a hut 20,000 years ago signaled shifting views of

death

Linking the dead with human-built structures may have brought the dead and living

closer

Middle Eastern hunter-gatherers changed their relationship with the dead nearly 20,000 years ago. Clues to that

spiritual shift come from the discovery of an ancient woman’s fiery burial in a hut at a seasonal campsite.

Burials of people in houses or other structures, as well as cremations, are thought to have originated in Neolithic

period farming villages in and around the Middle East no earlier than about 10,000 years ago. But those treatments of

the dead appear to have had roots in long-standing practices of hunter-gatherers, says a team led by archaeologists Lisa

Maher of the University of California, Berkeley and Danielle Macdonald of the University of Tulsa in Oklahoma.

The new find suggests that people started to associate the dead with particular structures at a time when groups of

hunter-gatherers were camping for part of each year at a hunting and trading site in eastern Jordan. A budding desire

to link the dead with human-built structures possibly reflected a belief that by doing so the dead would remain close to

the living, the scientists report in the March Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

Excavations at the ancient site, now called Kharaneh IV, in 2016 revealed a woman’s partial, charred skeleton on

the floor of a hut that had been lit on fire. Her body had been placed on its side with knees flexed. Analyses of

charring patterns on her bones and burned sediment surrounding her remains suggest the woman’s body was placed

inside the hut just before the brushwood structure was intentionally burned. Charcoal- and ash-rich sediment

borders where the hut once stood, a sign that the fire was confined to the structure. The hut’s walls apparently fell

inward after being set ablaze.

Radiocarbon-dated samples from the earthen floor near the woman’s remains date her interment to around 19,200

years ago.

Several Neolithic sites contain examples of the dead having been placed in or under burned houses, as well as

instances of bodies that were intentionally burned after death, says archaeologist Peter Akkermans of Leiden

University, who did not participate in the new research. “The work at Kharaneh IV now dates these practices to more

than 10,000 years earlier, in wholly different cultural settings of hunter-gatherer communities versus Neolithic farming

villages.”

Other social developments traditionally attributed to Neolithic farmers, including year-round settlements (SN: 8/30/10)

and pottery making (SN: 6/28/12), first appeared among hunter-gatherers.

Remains of at least three other huts have been found at Kharaneh IV, including one with graves beneath the floor that

contained two human skeletons (SN: 2/22/12). That roughly 19,400-year-old hut was also burned down, possibly

when the site’s occupants stopped using it but not as part of a human burial event.

The new discovery at Kharaneh IV “links the death of a person and the destruction or death of a building as part of a

funerary rite,” Maher says. Perhaps the hut was where the woman or her family lived, or perhaps she died there and the

structure was deemed off-limits, she suggests. Either way, Kharaneh IV was occupied for several generations after the

woman’s death, until roughly 18,600 years ago, so establishing a permanent place for her may have been considered

important.

Meanings and beliefs that Kharaneh IV residents attributed to burning a hut in which a dead woman’s body had been

placed are still a mystery, Maher says. The use of fire in that event might have signified some type of transformation,

rebirth, cleansing or life-and-death cycle, she suggests.

VIJETHA IAS ACADEMY

ADDRESS: 7/50, II FLOOR, NEAR ROOP VATIKA, SHANKAR ROAD, OLD RAJENDAR NAGAR, NEW DELHI — 110060

HOTLINE: 011- 42473555, 9650852636 , 7678508541 , DATABASE: WWW.VIJETHAIASACADEMY.COM

CURIOUS FEBURARY 2021

Humanlike thumb dexterity may date back as far as 2 million years

ago

Improved grip gave tool-wielding ancestors an advantage over related hominids

Thumb dexterity similar to that of people today already existed around 2 million years ago, possibly in some of the

earliest members of our own genus Homo, a new study indicates. The finding is the oldest evidence to date of an

evolutionary transition to hands with powerful grips comparable to those of human toolmakers, who didn’t appear for

roughly another 1.7 million years.

Thumbs that enabled a forceful grip and improved the ability to manipulate objects gave ancient Homo or a closely

related hominid line an evolutionary advantage over hominid contemporaries, says a team led by Fotios Alexandros

Karakostis and Katerina Harvati. Now-extinct Australopithecus made and used stone tools but lacked humanlike thumb

dexterity, thus limiting its toolmaking capacity, the paleoanthropologists, from Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in

Germany, found.

The researchers digitally simulated how a key muscle influenced thumb movement in 12 previously found fossil

hominids, five 19th century humans and five chimpanzees. Surprisingly, Harvati says, a pair of roughly 2-million-year

old thumb fossils from South Africa display agility and power on a par with modern human thumbs.

Scientists disagree about whether the South African finds come from early Homo or Paranthropus robustus, a species

on a dead-end branch of hominid evolution (SN: 4/2/20). But the thumb dexterity in those ancient fossils is

comparable to that found in members of Homo species that appeared after around 335,000 years ago, the researchers

report January 28 in Current Biology. That includes Neandertals from Europe and the Middle East, and a South

African hominid dubbed Homo naledi, which possessed an unusual mix of skeletal traits (SN: 5/9/17).

By comparison, they conclude, Homo or P. robustus possessed thumbs that were more forceful than those of three

several-million-year-old Australopithecus species, two of which have previously been proposed to have humanlike

hands (SN: 1/22/15).

“Australopithecus would probably be able to perform most [tool-related] hand movements, but not as efficiently as

humans or other Homo species we studied,” Harvati says. The tool-wielding repertoire of Australopithecus species

fell closer to that of modern chimpanzees, who use twigs to collect termites and rocks to crack nuts, she suggests (SN:

11/6/09).

Harvati’s team went beyond past efforts that focused only on the size and shape of ancient hominids’ hand bones.

Using data from humans and chimpanzees on how hand muscles and bones interact while moving, the researchers

constructed a digital, 3-D model to re-create how a key thumb muscle — musculus opponens pollicis — attached to a

bone at the base of the thumb and operated to bend the digit’s joint toward the palm and fingers.

These new models of how ancient thumbs worked underscore the slowness of hominid hand evolution, says

paleoanthropologist Matthew Tocheri of Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Canada. Australopithecus made and

used stone tools as early as around 3.3 million years ago (SN: 5/20/15). “But we don’t see major changes to the

thumb until around 2 million years ago, soon after which stone artifacts become far more common across the African

landscape,” he says.

Karakostis and Harvati’s 3-D models of ancient thumb dexterity represent a promising advance, says

paleoanthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri in Columbia. But further work needs to examine how

other thumb muscles interacted with musculus opponens pollicis to influence how that digit worked in different

hominid species, she adds.

In a related finding, Ward and her colleagues — including Tocheri — reported in 2014 that a roughly 1.42-million

year-old hominid finger fossil from East Africa pointed to an early emergence of humanlike manipulation skills.

VIJETHA IAS ACADEMY

ADDRESS: 7/50, II FLOOR, NEAR ROOP VATIKA, SHANKAR ROAD, OLD RAJENDAR NAGAR, NEW DELHI — 110060

HOTLINE: 011- 42473555, 9650852636 , 7678508541 , DATABASE: WWW.VIJETHAIASACADEMY.COM

CURIOUS FEBURARY 2021

VIJETHA IAS ACADEMY

ADDRESS: 7/50, II FLOOR, NEAR ROOP VATIKA, SHANKAR ROAD, OLD RAJENDAR NAGAR, NEW DELHI — 110060

HOTLINE: 011- 42473555, 9650852636 , 7678508541 , DATABASE: WWW.VIJETHAIASACADEMY.COM

CURIOUS FEBURARY 2021

VIJETHA IAS ACADEMY

ADDRESS: 7/50, II FLOOR, NEAR ROOP VATIKA, SHANKAR ROAD, OLD RAJENDAR NAGAR, NEW DELHI — 110060

HOTLINE: 011- 42473555, 9650852636 , 7678508541 , DATABASE: WWW.VIJETHAIASACADEMY.COM

CURIOUS FEBURARY 2021

VIJETHA IAS ACADEMY

ADDRESS: 7/50, II FLOOR, NEAR ROOP VATIKA, SHANKAR ROAD, OLD RAJENDAR NAGAR, NEW DELHI — 110060

HOTLINE: 011- 42473555, 9650852636 , 7678508541 , DATABASE: WWW.VIJETHAIASACADEMY.COM

You might also like

- White Shade: The Real-World Primer for the Black Professional WomanFrom EverandWhite Shade: The Real-World Primer for the Black Professional WomanNo ratings yet

- BiopsychDocument1 pageBiopsychJeri AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Special and Different: The Autistic Traveler: Judgment, Redemption, & VictoryFrom EverandSpecial and Different: The Autistic Traveler: Judgment, Redemption, & VictoryNo ratings yet

- What Squirt Teaches Me about Jesus: Kids Learning about Jesus while Playing with FidoFrom EverandWhat Squirt Teaches Me about Jesus: Kids Learning about Jesus while Playing with FidoNo ratings yet

- If I Were Born Here Volume II (Greece, India, Kenya, Mexico, Israel)From EverandIf I Were Born Here Volume II (Greece, India, Kenya, Mexico, Israel)No ratings yet

- Strangers' Voices In My Head: A Journey Through What Made Me Who I Am from My MindFrom EverandStrangers' Voices In My Head: A Journey Through What Made Me Who I Am from My MindNo ratings yet

- Extreme Rhyming Poetry: Over 400 Inspirational Poems of Wit, Wisdom, and Humor (Five Books in One)From EverandExtreme Rhyming Poetry: Over 400 Inspirational Poems of Wit, Wisdom, and Humor (Five Books in One)No ratings yet

- Colonial Comics, Volume II: New England, 1750–1775From EverandColonial Comics, Volume II: New England, 1750–1775Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Neutral Zone TechniqueDocument22 pagesNeutral Zone TechniqueRT CrNo ratings yet

- Be The ChangeDocument2 pagesBe The ChangeRT CrNo ratings yet

- Fixed Partial Dentures: Diagnosis and Treatment Planning For Fixed ProsthodonticsDocument6 pagesFixed Partial Dentures: Diagnosis and Treatment Planning For Fixed ProsthodonticspalliNo ratings yet

- Dr. R. Arthi MDS II YearDocument19 pagesDr. R. Arthi MDS II YearRT CrNo ratings yet

- Ref and Pic Removed LDDocument25 pagesRef and Pic Removed LDRT CrNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Evaluation of Conventional Bridgework: Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 1990, Volume 17, Pages 131-136Document7 pagesA Clinical Evaluation of Conventional Bridgework: Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 1990, Volume 17, Pages 131-136RT CrNo ratings yet

- Construction of A Custom-Shaded Interim Denture Using Visible-Light-Cured ResinDocument4 pagesConstruction of A Custom-Shaded Interim Denture Using Visible-Light-Cured ResinbkprosthoNo ratings yet

- Past Tropical Changes Drove Megafauna ExtinctionsDocument4 pagesPast Tropical Changes Drove Megafauna ExtinctionsRT CrNo ratings yet

- 11 03 2021 PDFDocument5 pages11 03 2021 PDFRT CrNo ratings yet

- Growing number of humans have extra artery showing evolutionDocument4 pagesGrowing number of humans have extra artery showing evolutionRT CrNo ratings yet

- TodayDocument4 pagesTodayRT CrNo ratings yet

- Depletion of Particular Brain Tissue Linked To Chronic Depression, Suicide: StudyDocument3 pagesDepletion of Particular Brain Tissue Linked To Chronic Depression, Suicide: StudyRT CrNo ratings yet

- Failing To Plan Is Planning To Fail"Document39 pagesFailing To Plan Is Planning To Fail"RT CrNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Intraoral Evaluation of Planned Fixed Partial Denture Pontics Using Silicone PuttyDocument4 pagesPreoperative Intraoral Evaluation of Planned Fixed Partial Denture Pontics Using Silicone PuttyRT CrNo ratings yet

- Be The Brand Ambassador of Tribes India" and Be A Friend of Tribes India' Contest Launched by TRIFED in Association WithDocument5 pagesBe The Brand Ambassador of Tribes India" and Be A Friend of Tribes India' Contest Launched by TRIFED in Association WithRT CrNo ratings yet

- First European Homo Sapiens Mixed With Neanderthals, DNA Study ShowsDocument4 pagesFirst European Homo Sapiens Mixed With Neanderthals, DNA Study ShowsRT CrNo ratings yet

- Sri Venkateshwaraa Dental College Department of Prosthodontics and Crown & BridgeDocument2 pagesSri Venkateshwaraa Dental College Department of Prosthodontics and Crown & BridgeRT CrNo ratings yet

- Complete Denture Evaluation DCNADocument17 pagesComplete Denture Evaluation DCNAAravind Krishnan80% (15)

- More than 90% Crimes SCs PendingDocument2 pagesMore than 90% Crimes SCs PendingRT CrNo ratings yet

- Veneers Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesVeneers Literature ReviewRT CrNo ratings yet

- Indians relate more to regional identity but accept other languagesDocument4 pagesIndians relate more to regional identity but accept other languagesRT CrNo ratings yet

- Modern Development Threatens Prehistoric Sites Across IndiaDocument2 pagesModern Development Threatens Prehistoric Sites Across IndiaRT CrNo ratings yet

- When Did Humans First Go To War?: VijethaDocument5 pagesWhen Did Humans First Go To War?: VijethaRT CrNo ratings yet

- Gene Therapy Effective TSC MiceDocument2 pagesGene Therapy Effective TSC MiceRT CrNo ratings yet

- Why Evolution Always Goes in One Direction: VijethaDocument4 pagesWhy Evolution Always Goes in One Direction: VijethaRT CrNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Pressures Led Humans to Become More TolerantDocument3 pagesEvolutionary Pressures Led Humans to Become More TolerantRT CrNo ratings yet

- Trifed Signs Mou With Government of Arunachal Pradesh For The Implementation of MSP For MFP Scheme and Van Dhan YojanaDocument2 pagesTrifed Signs Mou With Government of Arunachal Pradesh For The Implementation of MSP For MFP Scheme and Van Dhan YojanaRT CrNo ratings yet

- Darwin and Race: Three Strikes, He's Out: Vijetha Ias AcademyDocument3 pagesDarwin and Race: Three Strikes, He's Out: Vijetha Ias AcademyRT CrNo ratings yet

- The Scientific Argument For Marrying Outside Your Caste: VijethaDocument7 pagesThe Scientific Argument For Marrying Outside Your Caste: VijethaRT CrNo ratings yet

- Biological Causes For AggressionDocument7 pagesBiological Causes For Aggressionblah100% (1)

- Sts Cheat Sheet of The BrainDocument30 pagesSts Cheat Sheet of The BrainRahula RakeshNo ratings yet

- Gestalt Psychology and Learner Centered TeachingDocument4 pagesGestalt Psychology and Learner Centered TeachingJeanelle Marie RamosNo ratings yet

- The Neural Basis of Romantic LoveDocument6 pagesThe Neural Basis of Romantic LoveBooster CNo ratings yet

- PlasticityDocument2 pagesPlasticityEmilie Cevallos ParedesNo ratings yet

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) : Presented by Vajarala AshikhDocument34 pagesElectroencephalogram (EEG) : Presented by Vajarala Ashikhzohaib100% (1)

- Are Sex-Related Category-Specific Differences in Semantic Tasks Innate or Influenced by Social Roles?Document9 pagesAre Sex-Related Category-Specific Differences in Semantic Tasks Innate or Influenced by Social Roles?argiaescuNo ratings yet

- Human Death As A Concept of Practical Philosophy PDFDocument16 pagesHuman Death As A Concept of Practical Philosophy PDFPABLO MAURONo ratings yet

- Basic Approach to Brain CT: Key Anatomy, Pathologies & Imaging FindingsDocument62 pagesBasic Approach to Brain CT: Key Anatomy, Pathologies & Imaging FindingsS B SayedNo ratings yet

- Biology 1413 Introductory Zoology Lab ManualDocument128 pagesBiology 1413 Introductory Zoology Lab ManualTanuj Paraste100% (1)

- Olivia Tween COGS Aphantasia Thesis Final Version PDFDocument23 pagesOlivia Tween COGS Aphantasia Thesis Final Version PDFJORGE ENRIQUE CAICEDO GONZ�LES100% (1)

- Brain Herniation SyndromeDocument28 pagesBrain Herniation SyndromeSarahScandy100% (4)

- The Matrix Deciphered Prerelease by The Saint PDFDocument308 pagesThe Matrix Deciphered Prerelease by The Saint PDFvickie100% (1)

- Mesolimbic Vs NigrostriatalDocument7 pagesMesolimbic Vs NigrostriatalAmrit SoniaNo ratings yet

- Materialism Christian BeliefDocument43 pagesMaterialism Christian BeliefLamija NukicNo ratings yet

- Morcan - GeniusDocument40 pagesMorcan - Geniusmihai100% (1)

- LA Prediction Dec 10th To Dec 16th 2022 PDFDocument375 pagesLA Prediction Dec 10th To Dec 16th 2022 PDFSahil MishraNo ratings yet

- Apostila 2° Ano - CópiaDocument50 pagesApostila 2° Ano - CópiajoaodelpadreNo ratings yet

- A2 Level Biology: Coordination-Lecture 2 by Muhammad Ishaq KhanDocument7 pagesA2 Level Biology: Coordination-Lecture 2 by Muhammad Ishaq KhanAwais BodlaNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis in Patient With Undifferentiated SchizophreniaDocument30 pagesCase Analysis in Patient With Undifferentiated SchizophreniaSolsona Natl HS MaanantengNo ratings yet

- NT57-sat TestDocument57 pagesNT57-sat Testhanh dao thuyNo ratings yet

- Assessment 8Document3 pagesAssessment 8Dianne LarozaNo ratings yet

- Neuralink TechnologyDocument6 pagesNeuralink TechnologyNeha Lodhe100% (1)

- Teens Brain Under ConstructionDocument12 pagesTeens Brain Under ConstructionDoru-Mihai Barna100% (2)

- EEG PresentationDocument39 pagesEEG PresentationAlfred Fredrick100% (1)

- Bibliografie UBB PsihologieDocument2 pagesBibliografie UBB PsihologieAdina CarterNo ratings yet

- EDU 537 Module 9 ExplanationDocument8 pagesEDU 537 Module 9 Explanationangie marie ortegaNo ratings yet

- Waleed Sp20-Bba-028 MarketingDocument3 pagesWaleed Sp20-Bba-028 MarketingZain MunirNo ratings yet

- Seeking Wisdom in The Age of (Mis) Information & Noise - Dec 2017Document59 pagesSeeking Wisdom in The Age of (Mis) Information & Noise - Dec 2017Vishal Safal Niveshak Khandelwal100% (3)

- Imagery and Training The Minds Eye - Lee PulosDocument12 pagesImagery and Training The Minds Eye - Lee Pulosmugume ignatius100% (2)