Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Ethnopragmatics of Rioplatense Spanish: Keywords and Cultural Scripts For The Language Classroom

Uploaded by

Federico MininOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ethnopragmatics of Rioplatense Spanish: Keywords and Cultural Scripts For The Language Classroom

Uploaded by

Federico MininCopyright:

Available Formats

The

Ethnopragmatics of Rioplatense Spanish: Keywords and Cultural Scripts for the

language classroom

HDR Candidate: Eric Jan Hein

Principal Supervisor: Cliff Goddard

Associate Supervisor: Susana Eisenchlas

SUMMARY

I will (1) investigate the links between (a) Rioplatense Spanish speech practices and (b) tacit norms and values

widely held in Latin America. Based on (1), I will (2) develop pedagogical material that assists language

students in gaining a culture-internal perspective on culturally-motivated aspects of the Spanish model of

conversational interaction which present challenges for them. To attain (1) and (2), I will use the Natural

Semantic Metalanguage approach, which captures culture-specific speech practices and other cultural

phenomena using simple, non-ethnocentric, cross-translatable terms. My project is a contribution to

ethnopragmatics, and meets the need to develop interculturally competent language students.

Words: 100 of 100

INTRODUCTION

My project has a double purpose: (a) to undertake an ethnopragmatic analysis of Rioplatense

Spanish (i.e. Buenos Aires´ Spanish) keywords, speech practices, values and attitudes, using the Natural

Semantic Metalanguage framework [34; 35; 36; 39; 52; 53; 64], and (b) on the basis of this analysis, to

develop pedagogical material that can integrate intercultural communicative competence in foreign

language instruction.

The term ethnopragmatics designates an approach to language in use that sees culture as playing a

central explanatory role, and which opens the way for links to be drawn between language and other

culture phenomena [40: p. 66]. In language teaching, the concept intercultural communicative

competence focuses on the idea that to successfully communicate in a foreign language does not only

involve a purely linguistic ability (e.g. correct use of grammar rules), but also an ability to interact with

others who are culturally different from oneself, based on an understanding of the norms and values

held in their community and encoded through their everyday speech practices [4; 5; 50; 56].

With increased globalization and migration there has been a growing recognition for the need for an

intercultural focus in language education [50]. Influential documents issued as guidelines to language

teachers, such as the USA´s ”Standards in Foreign Language Learning” [1] and Europe´s CEFR [8], are

firmly based in a sociocultural approach to language teaching which emphasizes intercultural

competence as an important goal for language learners [48]. In Australian higher education language

programs, and particularly at the School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science at Griffith

University, the importance of integrating a critical “languaculture dimension” within the curricula is also

being increasingly recognized [10].

Despite the widespread agreement about the need to develop interculturally competent language

students, there exists a serious gap between institutional guidelines and theory on the one hand and

practice on the other [3: p. 124; 10; 11; 14; 45]. An obstacle here is the lack of pedagogical material

designed for that purpose [7; 14: p. 32; 15]. The development of such material will constitute a step

forward in bridging this gap in the field of language education.

RELEVANCE

Spanish is the main language of communication in 21 countries and is 2nd by number of native

speakers in the world [43]. Because of the importance Spanish has today in international, political,

economic and cultural contexts, my project will focus on that language (which, I should add, is my

mother tongue), but the insights it aims to produce will have import for foreign language teaching at

large. Furthermore, the ethnopragmatic investigation I will undertake is valuable in and of itself, in that

it will unlock the relationship between (a) everyday Spanish language and (b) tacit norms and values

widely held in Spanish-speaking societies. In broader perspective, this project is a contribution to the

field of intercultural communication, which stresses the need for intercultural dialogue in today´s

increasingly diverse and interconnected world.

THEORY AND METHODS

My project´s theoretical frame is the ethnopragmatic paradigm, the objective of which is to produce,

from a culture-internal perspective, understandings of the “how and why” of discourse practices in the

diverse languages of the world [40]. To attain this, ethnopragmatics uses the Natural Semantic

Metalanguage (NSM) approach originated by the Australian semanticists Anna Wierzbicka (ANU), Cliff

Goddard (Griffith University) and colleagues [28; 30; 34; 35; 36; 52; 53; 61; 64]. This approach employs

a small core of 65 basic, culturally-shared, intuitively self-explanatory meanings—known as semantic

primes—as its vocabulary of semantic and pragmatic description across languages and cultures [33: p.

3]. Based on decades of cross-linguistic semantic research, semantic primes are hypothesized to have

concrete linguistic exponents (i.e. words or other linguistic expressions) in all natural languages. They

can also be combined, according to grammatical patterns which also appear to be universal, to form

simple phrases and sentences. Semantic primes and their grammatical frames (and certain complex

units called semantic molecules) make up the NSM, a cross-translatable “mini-language” which works

as a tool for linguistic and cultural analysis [31; 33: p. 3]. Using simple terms that can be understood by

cultural outsiders, one can represent from an insider´s point of view the meanings of complex and

culture-specific words, grammatical constructions and other speech practices found in any language [33;

38]. This technique is called semantic explication [31: p. 461], and its application for analysing cultural

keywords [60; 62; 63] has particular importance in ethnopragmatics. Cultural keywords are highly

salient, culture-rich and translation-resistant words that occupy focal points in cultural ways of

thinking, acting, feeling and speaking [40: p. 71]. NSM is also used to capture the meaning of beliefs,

values, attitudes, aspects of interpersonal style, norms and other practices widely held in a given

culture. This technique is called cultural script [29; 40: pp. 71-72].

The NSM approach has made considerable progress in its attempt to avoid the problem of

terminological ethnocentrism so common in cultural studies and universalist pragmatics: the imposition

of an inaccurate outsider perspective by using complex, culture-specific terms of one language/culture

to describe the meanings and values of another language/culture. Furthermore, because they are easily

translatable to any language and accessible to language learners, scripts and explications can be readily

adapted as “pedagogical scripts” to develop the intercultural competence component in language

teaching [16; 29: pp. 156-157; 32: p. 114; 37: pp. 159-162; 40: p. 80; 46: pp. 192-196].

ETHNOPRAGMATICS OF SPANISH

Travis´ ethnopragmatic studies on Colombian Spanish have shown how the everyday use of

diminutives, terms of endearment, discourse markers and certain cultural keywords (such as

“confianza”, “calor humano”, and “vínculos”1) realize a cultural model of conversational interaction

widely held in Colombia where high value is placed on displaying affection for others and on affirming

the tie that exists in relationships [57; 58; 59]. In accordance with ethnographic and linguistic-

anthropological studies [12; 18; 19; 20; 21; 41; 42; 54; 55], Travis suggests that “much of what is

presented [in this model] also applies to other Latin American countries, as well as to other Latin

countries, such as Spain” [59: p. 201], and the same stance is supported in Osmann´s study showing how

the keyword “calor humano” is fundamental to interpersonal interaction throughout the Spanish-

speaking world [51].

In line with these studies, my working hypothesis is that there are both (a) high-level “master

scripts” [37: pp. 157-158] which function as a shared interpretative background in conversational

interaction across Latin American Spanish-speaking societies, and (b) low-level, culture-specific scripts

for interaction, linked with the particular political, cultural and migratory histories of each society.

Focusing on the Rioplatense dialect of Buenos Aires (Argentina), the task I propose is to track down and

produce an ethnopragmatic description of the linguistic forms and practices through which the

Porteños (Buenos Aires inhabitants) either realize or diverge from that shared model of everyday

conversation.

The divergence of Rioplatense speech practices is strongly linked with the exceptional

language/culture contact situation that took place in Buenos Aires from the end of the 19th century

1

The English terms “trust”, “human warmth”, and “bonds” (loosely) capture their meanings.

until the first decades of the 20th century, where great European—particularly Italian—immigration

waves drastically modified the sociolinguistic landscape of the area. The effects of this contact are to

be found not only in the lexicon, intonation, and phonetics specific of today´s Rioplatense Spanish [13;

22; 23; 24; 25; 26; 27; 44], but also in deeply rooted cultural scripts that guide Porteños´ ways of

thinking and speaking [2; 6; 49]. A contrastive perspective with other Spanish dialects will therefore be

of paramount importance.

In line with the ethnopragmatic paradigm, my approach will place particular importance on linguistic

evidence I will gather through:

v Corpus del Español (100 million words, to be expanded to 2 billion, including texts from the

2010s, allowing comparison of spoken variations across Spanish-speaking countries) [9]

v Language/culture consultants

v Semantic consultation sessions [39; 47] to be carried out in Buenos Aires with groups of

native Spanish speakers

PEDAGOGICAL MATERIAL

The material will be designed for students studying Spanish at the Bachelor of Language and

Linguistics at Griffith University. The aim is to assist them in gaining a culture-internal perspective on

culturally-motivated aspects which are central in the Spanish model of conversational interaction but

are different in their home culture, and thus present special challenges for them. Explicit instruction

using scripts and explications should help them gain proficiency in those aspects, and also become

aware of differences and similarities between their own cultural model and that of the target language.

Based on (a) a survey administered to Bachelor students of Spanish where they report on their

experiences of everyday conversation during their study-abroad semester in Spanish-speaking countries

[17], and (b) personal communication with Spanish teachers at higher education and international

specialists in foreign language acquisition, I have made a provisional list of those aspects:

v Complex greeting/leave-taking routines

v Conversational management strategies (e.g. preferences for overlap, latching and high-

involvement; turn-taking patterns; back-channelling; conversation closers)

v Interpersonal expressiveness: in prosody, high frequency interjections, intensifiers,

superlative suffix, diminutives, expressions of warm praise, and compliments

v Terms of address: terms of endearment, hypocoristics, vocatives, quasi-kin terms, various

2.p.s. pronouns

v Colloquial language and slang

The material will be elaborated in line with pedagogical guidelines that can be found in the

ethnopragmatic and NSM bibliography. It will be tried out in a pedagogical intervention with the

students and assessed through a pretest-posttest study.

TIMEPLAN

Semester

TASK

1 2 3 4 5 6

Reading stage

Data Consultation + Corpus study

Ethnopragmatic gathering Fieldwork in Buenos Aires

research

Analysis using NSM

Design of pedagogical material & intervention

Pedagogical intervention

Assessment of material & intervention

Dissertation

Over the period of my candidature, I also have the intention to publish journal articles, to present at

conferences—e.g. Australian Linguistics Society Annual Conference, to be held at Monash University,

December 7-9 2016—and to participate in the NSM semantic workshops held every year at ANU.

Eric Jan Hein

LIST OF REFERENCES

1. ACTFL (1996) Standards in Foreign Language Learning: Preparing for the 21st Century. Lawrence, KS: Allen

Press.

2. Aguinis, Marcos (2001) El atroz encanto de ser argentinos. Buenos Aires: Planeta

3. Andersen, Hanne Leth; Fernández, Susana; Fristrup, Dorte & Brigit Henriksen (2015) Fagdidaktik i sprogfag.

København: Frydenlund.

4. Byram, Michael (1997) Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence, Clevedon:

Multilingual Matters.

5. Byram, Michael (2012) Conceptualizing intercultural (communicative) competence and intercultural

citizenship. In Jane Jackson (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication, 85-

97. London & New York: Francis & Taylor.

6. Cancellier, Antonella (2011) El español rioplatense en los estudios dialectológicos de Giovanni Meo Zilio. In

Rolf, Kailuweit and Ángela, L. DiTullio (eds.), El español rioplatense: lengua, literaturas, expresiones culturales ,

137–151. Frankfurt: Vervuert.

7. Chapelle, Carol A. (2010) If intercultural competence is the goal, what are the materials? In Beatrice Dupuy &

Linda Waugh (Eds.), Proceedings of Second International Conference on the Development and Assessment of

Intercultural Competence, Vol. 1, 27-50.

8. Council of Europe (2001) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching,

Assessment” (CEFR). Online. Available: http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf

(Accessed 1 June 2015)

9. Davies, Mark. (2002-) Corpus del Español: 100 million words, 1200s-1900s. Available online at

www.corpusdelespanol.org

10. Díaz, Adriana (2011) Developing a Languaculture Agenda in Australian Higher Education Language Programs.

Thesis (PhD Doctorate), Griffith University, Brisbane.

11. Díaz, Adriana (2013) Developing Critical Languaculture Pedagogies in Higher Education. Theory and Practice.

Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

12. Diaz Guerrero, Rogelio, and Lorand B. Szalay (1991) Understanding Mexicans and Americans: Cultural

Perspectives in Conflict. New York: Plenum Publishing.

13. Ennis, Juan Antonio (2015) Italian-Spanish Contact in Early 20th Century Argentina, Journal of language

contact 8: 112-145.

14. Fernández, Susana S., and María Isabel Pozzo (2014) La competencia intercultural como objetivo en la clase

de ELE, In Susana Fernández and María Isabel Pozzo (eds.), Diálogos Latinoamericanos: Globalización,

interculturalidad y enseñanza de español: Nuevas propuestas didácticas y evaluadoras, 22: 27-45

15. Fernández, Susana S. (2015) Concepciones de los profesores daneses acerca de la competencia intercultural

en la clase de español como lengua extranjera. In Milli Mála - Journal of Language and Culture 7, 95-120.

16. Fernández, Susana (2016) Possible contributions of Ethnopragmatics to second language learning and

teaching. In Sten Vikner, Henrik Jørgensen & Elly van Gelderen (eds.) Let us have articles betwixt us – Papers

in Historical and Comparative Linguistics in Honour of Johanna L. Wood. Dept. of English, School of

Communication & Culture, Aarhus University, pp. 185-206.

17. Fernández, Susana S. (unpublished raw data) Bringing Spanish cultural scripts and values for interpersonal

style into the Danish L2 classroom: Student survey.

18. Fitch, Kristine L. (1989) Communicative enactment of interpersonal ideology: Personal address in urban

Colombian society. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Washington, Washington DC.

19. Fitch, Kristine L. (1990) A ritual for attempting leave-taking in Colombia Research on Language and Social

Interaction 24: 209-224.

20. Fitch, Kristine L. (1991) The interplay of linguistic universals and cultural knowledge in personal address:

Colombian madre terms. Communication monographs 58 (3): 254-272.

21. Fitch, Kristine L. (1994) A cross-cultural study of directive sequences and some implicationsfor compliance-

gaining research. Communication monographs 61(3): 185-209

22. Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz (1979a) La asimilación lingüística de los inmigrantes. Mantenimiento y

cambio de lengua en el sudoeste bonaerense. Bahía Blanca: Departamento de Humanidades de la Universidad

Nacional del Sur.

23. Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz (1979b) Dinámica social de un cambio lingüístico: la reestructuración

de las palatales en el español bonaerense. México: UNAM.

24. Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz (1987) El español bonaerense. Cuatro siglos de evolución lingüística

(1580–1980), Buenos Aires: Hachette.

25. Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz (1992) El español de América. Madrid: Mapfre.

26. Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz (1996) Contacto lingüístico: lenguas inmigratorias. Signo & Seña 6.

Contactos y transferencias lingüísticas en Hispanoamérica: 439–457.

27. Fontanella de Weinberg, María Beatriz (2004) El español de la Argentina y sus variedades regionales. Bahía

Blanca: Fundación Bernardino Rivadavia.

28. Goddard, Cliff (2002) The search for the shared semantic core of all languages. In Cliff Goddard and Anna

Wierzbicka (eds). Meaning and Universal Grammar - Theory and Empirical Findings. Volume I. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins. pp. 5-40

29. Goddard, Cliff (2004) "Cultural scripts": A new medium for ethnopragmatic instruction. In: Michel Achard and

Susanne Niemeier (eds), Cognitive Linguistics, Second Language Acquisition, and Foreign Language Teaching.

Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 143-163.

30. Goddard, Cliff (2008) Natural Semantic Metalanguage: The state of the art. In Cliff Goddard (ed.), Cross-

Linguistic Semantics, 1-34. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

31. Goddard, Cliff (2010a) The Natural Semantic Metalanguage approach. In Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog (eds.)

The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 459-484.

32. Goddard, Cliff (2010b). Cultural scripts: applications to language teaching and intercultural communication.

Studies in Pragmatics (Journal of the China Pragmatics Association) 3, 105-119.

33. Goddard, Cliff (2011) Ethnopragmatics: a new paradigm. In Cliff Goddard (ed.), Applications of Cognitive

Linguistics [ACL]: Ethnopragmatics: Understanding Discourse in Cultural Context. Munchen, DEU: Walter de

Gruyter, 2011. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 19 September 2015.

34. Goddard, C. (2011b) Semantic Analysis – A Practical Introduction. [Revised 2nd edition] Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

35. Goddard, Cliff, and Anna Wierzbicka (eds.) (1994) Semantic and Lexical Universals: Theory and empirical

findings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

36. Goddard, Cliff, and Anna Wierzbicka (eds.) (2002) Meaning and Universal Grammar: Theory and empirical

findings, (two volumes). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

37. Goddard, Cliff and Anna Wierzbicka (2004) Cultural Scripts: What are they and what are they good for?

Intercultural Pragmatics 1(2), 153-166.

38. Goddard, Cliff and Anna Wierzbicka (2007) Semantic primes and cultural scripts in language learning and

intercultural communication. In Gary Palmer and Farzad Sharifian (eds.) Applied Cultural Linguistics:

Implications for second language learning and intercultural communication. Amsterdam: John Benjamins,

105-124. (retrieved from Pre-publication version available in:

(https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/347525/goddard-wierzbicka-applied-nsm.pdf)

(note page numbers do not match published version).

39. Goddard, Cliff and Anna Wierzbicka (2014) Words and Meanings: Lexical Semantics Across Domains,

Languages, and Cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

40. Goddard, Cliff, and Zhengdao Ye (2014) Ethnopragmatics. In Farzad Sharifian (ed.), The Routledge Handbook

of Language and Culture, 66-83. London & New York: Taylor & Francis.

41. Gudykunst, William B., and Yuko Matsumoto (1996) Cross cultural variability of communication in personal

relationship. In Communication in Personal Relationships across Cultures, William B. Gudykunst, Stella Ting-

Tooney, and Tsukasa Nishida /eds.), 19-56. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

42. Hofstede, Geert (1980) Culture´s Consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

43. Instituto Cervantes (2015) El Español: Una Lengua Viva: Informe 2015. Department of Digital Communication

of Instituto Cervantes. Digital edition available online: http://eldiae.es/wp-

content/uploads/2015/06/espanol_lengua-viva_20151.pdf (accessed 20 September 2015)

44. Iribarren Castilla, Vanesa G. (2009) Investigación de las hablas populares bonaerenses: el lunfardo. (PhD

thesis). Universidad complutense de Madrid.

45. Kelly, Michael (2012) Second language teacher education. In Jane Jackson (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of

Language and Intercultural Communication, 409-421. London & New York: Francis & Taylor.

46. Levisen, Carsten (2012) Cultural Semantics and Social Cognition: A case study on the Danish universe of

meaning. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

47. Levisen, Carsten (forthcoming) The Sonic Semantics of Reggae: Language Ideology and Emergent Socialities in

Postcolonial Vanuatu. In Sippola, Eeva, Schneider Britta, and Levisen, Carsten (eds.). Language Ideologies in

Music: Emergent Socialities in the Age of Transnationalism. Special Issue for Language and Communication.

48. Lu, Peih-ying, and John Corbett (2012) An intercultural approach to second language education and

citizenship. In Jane Jackson (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication,

325-339. London & New York: Francis & Taylor.

49. Mafud, Julio (1965) Psicología de la viveza criolla. Buenos Aires: Editorial Americalee

50. Moeller, Aleidine J. and Nugent, Kristen (2014) Building intercultural competence in the language classroom.

In Stephanie Dhonau (ed.), Unlock the gateway to communication: Selected Papers from the 2014 Central

States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 1-18. Eau Claire: Johnson Litho Graphics.

51. Osmann, Randi (2015) Metaforer, kultur og sprog: Betydningen af ’varme’ for interpersonelle relationer i den

spansktalende verden. Master´s thesis. Spansk og spanskamerikansk sprog, litteratur og kultur, IÆK, ARTS,

Aarhus Universitet.

52. Peeters, Bert (ed.) (2006) Semantic Primes and Universal Grammar: Empirical findings from the Romance

languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

53. Peeters, Bert. 2015 (eds.) Language and Cultural Values: Adventures in applied ethnolinguistics. Special issue

of International Journal of Language and Culture 2:2.

54. Placencia, María Elena (1996) Politeness in Ecuadorian Spanish. Multilingua 151: 13-34.

55. Placencia, María Elena (1997) Address form in Ecuadorian Spanish. Hispanic Linguistics 91: 165-202.

56. Savignon, S. (2004) Communicative language teaching. In Michael Byram (ed.), The Routledge Encyclopedia of

Language Teaching & Learning, 124-129. London: Routledge.

57. Travis, Catherine (1998) Bueno: A Spanish Interactive Discourse Marker. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth

Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: General Session and Parasession on Phonetics and

Phonological Universals, 268-279.

58. Travis, Catherine (2004) The ethnopragmatics of the diminutive in conversational Colombian Spanish.

Intercultural Pragmatics 1: 249-274.

59. Travis, Catherine (2011) The communicative realization of confianza and calor humano in Colombian Spanish.

In Cliff Goddard (ed.), Applications of Cognitive Linguistics [ACL]: Ethnopragmatics: Understanding Discourse

in Cultural Context. Munchen, DEU: Walter de Gruyter, 2011. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 19 September 2015.

60. Wierzbicka, Anna (1992) Semantics, Culture, and Cognition: Universal human concepts in culture-specific

configurations. New York: Oxford University Press.

61. Wierzbicka, Anna (1996) Semantics: Primes and universals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

62. Wierzbicka, Anna (1997) Understanding Cultures through Their Keywords: English, Russian, Polish, German

and Japanese. New York: Oxford University Press.

63. Wierzbicka, Anna (2006) English: Meaning and culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

64. Wierzbicka, Anna (2013) Imprisoned in English: The Hazards of English as the Default Language. Oxford:

Oxford

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Learning Objectives: PlyometricsDocument30 pagesLearning Objectives: Plyometricsdna sncNo ratings yet

- 02 Laboratory Exercise 1Document2 pages02 Laboratory Exercise 1Ryan LumpasNo ratings yet

- Performance Appraisal System in The Cyprus Civil ServiceDocument23 pagesPerformance Appraisal System in The Cyprus Civil ServiceBETELHEM ABDUSHE0% (1)

- White Collar CrimeDocument49 pagesWhite Collar CrimeAnjaniNo ratings yet

- Southeast Asian HistoriographyDocument9 pagesSoutheast Asian HistoriographyRitikNo ratings yet

- From Farm To Table: Tri-City TimesDocument24 pagesFrom Farm To Table: Tri-City TimesWoodsNo ratings yet

- Notes On Law of CrimesDocument9 pagesNotes On Law of CrimesRajveer Singh SekhonNo ratings yet

- (123doc) Practice Test 2 Advanced LevelDocument9 pages(123doc) Practice Test 2 Advanced LevelHùng ĐihNo ratings yet

- Revalidated Oral Com Module Q2 Week 5 8 For Printing EditedDocument35 pagesRevalidated Oral Com Module Q2 Week 5 8 For Printing EditedHazel Mulano-ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Constitution and by LawsDocument6 pagesConstitution and by LawsMatta, Jherrie MaeNo ratings yet

- Contemporary WorldDocument10 pagesContemporary WorldEuwin RamirezNo ratings yet

- National Institute of Technology, Rourkela 2013 Non TeachingDocument6 pagesNational Institute of Technology, Rourkela 2013 Non TeachingRajesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Week 3 Org & ManagementDocument5 pagesWeek 3 Org & ManagementVia Terrado CañedaNo ratings yet

- Attali - Noise - CH 1 PDFDocument14 pagesAttali - Noise - CH 1 PDFCullynNo ratings yet

- Bme 14 (Reflection 2)Document1 pageBme 14 (Reflection 2)HamieWave TVNo ratings yet

- The Difference Between Esp and EgpDocument3 pagesThe Difference Between Esp and EgpErlan PalayukanNo ratings yet

- Exam Booster 26-50Document25 pagesExam Booster 26-50Florina ConstantinNo ratings yet

- Impact Factor and Citation Metrics: What Do They Really Mean?Document38 pagesImpact Factor and Citation Metrics: What Do They Really Mean?Islam HasanNo ratings yet

- Investement ASSignt ELIOCDocument42 pagesInvestement ASSignt ELIOCsamuel debebeNo ratings yet

- American Capitalism EssayDocument2 pagesAmerican Capitalism EssayMicah Gibson100% (1)

- Powerlite Fitzgerald Price Guide 2020Document19 pagesPowerlite Fitzgerald Price Guide 2020Simo RounelaNo ratings yet

- Career in Banking BrochureDocument4 pagesCareer in Banking BrochureDip JakirNo ratings yet

- Legal Profession Pre Post and ContemporaryDocument17 pagesLegal Profession Pre Post and Contemporaryakash tiwariNo ratings yet

- CWIHPBulletin6-7 p2 PDFDocument96 pagesCWIHPBulletin6-7 p2 PDFanissa antania hanjaniNo ratings yet

- Audit TTTDocument15 pagesAudit TTTMaulida insNo ratings yet

- STJ OPT: BukelDocument18 pagesSTJ OPT: BukelMarian GrigoreNo ratings yet

- Concerned Citizens Against WojcikDocument1 pageConcerned Citizens Against WojcikConcerned Citizens Against Wojcik100% (2)

- HR Business Partner SalesDocument3 pagesHR Business Partner SalesanujdeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Observation 2 7 Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesObservation 2 7 Lesson Planapi-503230884No ratings yet

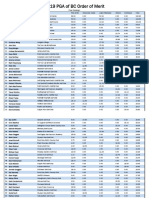

- 2019 PGA of BC Order of MeritDocument8 pages2019 PGA of BC Order of MeritPGA of BCNo ratings yet