Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Great Sioux Nation Tribes and Seven Council Fires

Uploaded by

Степан ВасильевCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Great Sioux Nation Tribes and Seven Council Fires

Uploaded by

Степан ВасильевCopyright:

Available Formats

T O U R S

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any

electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems

without written permission from Native Discovery.

Great “Sioux” Nation Tribes and

Seven Council Fires T O U R S

Where did the name Great Sioux Nation come from?

The US government took the word Sioux from Nadowesioux, which comes from a Chippewa

(Ojibway) word which means little snake or enemy. The French traders and trappers who

worked with the Chippewa people shortened the word to Sioux. Sioux is a collective term

referring to the dialects of Native Americans who lived in present-day South Dakota. Each of

the bands within the Sioux Nation spoke one of three dialects. The Santee spoke Dakota; the

Yankton, Nakota; and the Teton, Lakota.

How many Indian Tribes are in South Dakota?

There are nine tribes in South Dakota. Six of the tribes reside on federally recognized

reservations—the Cheyenne River, Oglala (Pine Ridge Reservation), Rosebud, Standing Rock,

Crow Creek, and Lower Brule Tribes. The other three tribes reside on what is officially known

as tribal lands—the Yankton, Flandreau Santee Tribes and the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate (Lake

Traverse Tribal Lands).

What ethnic groups make up the “Sioux” people?

The “Sioux” people include three ethnic groups. Some of the ethnic groups are divided into

sub-groups and then are further divided into bands. The Yankton-Yanktonai, the smallest

division, reside on the Yankton tribal lands in South Dakota and the northern portion

of Standing Rock Reservation. The Santee live mostly in Minnesota and Nebraska, but

include bands in the Sisseton-Wahpeton and Flandreau/Santee tribal lands, and Crow Creek

Reservations in South Dakota. The Lakota include seven bands and are the western-most of

the three groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota.

What are the Seven Council Fires?

When the “Great Sioux Nation” was formed by the US government, it was divided into

seven tribes. The “Sioux” people referred to their Nation as the “Seven Council Fires” (Oceti

Sakowin). Each fire represented a family or band (tiyospaye). The Seven Council Fires

included the following:

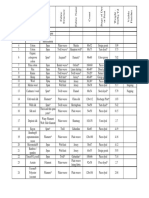

1. Mdewakantonwan - Spirit Lake People

2. Wahpekute - Shooters among the Leaves

3. Sissetonwan - People of the Fish Ground (Sisseton)

4. Wahpetonwan - Dwellers among the Leaves (Wahpeton)

5. Ihanktonwana - Little Dwellers at the End (Yanktonais)

6. Ihanktonwan - Dwellers at the End (Yankton)

7. Tetonwan - Dwellers on the Plains (Teton, commonly referred to as Lakota)

* Lakota words appear in italics continued on back

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Lakota-Nakota-Dakota T O U R S

Seven Council Fires-Oceti Sakowin

4. Sisitonwan

Camping among Swamps

N

2. Wahpekute

Leaf Shooters 5. Ihanktonwan

Camping at the End

W

E

1. Mdewakantonwan

Camping at spirit Lake

6. Ihanktonwanna

3. Wahpetonwan S Camping at the Little End

Camping among Leaves

7. Titonwan

Camping on the Plains

Dakota Nakota Lakota

4 + 2 + 1 = 7

Note: Walker, R. James, The Seven Council Fires. The Structure of Society. p15

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Lakota People

T O U R S

What brought Lakota people to present-day South Dakota?

The Lakota people who reside on the Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, and Rosebud Reservations

originally lived in the forests of north central Minnesota, where they subsisted on hunting,

fishing, and gathering. White encroachment into the area in the mid-1700s moved the Lakota

people into large parts of five Plains states, where they became expert hunters, traders, and

horsemen. Buffalo (Tatanka) became a primary source of food. By 1778, the Lakota people

had discovered the Black Hills in western South Dakota.

Seven Bands of the Lakota Nation

There are seven bands of the Lakota Nation. Lakota means “allies” or “friends.” It is the

name that people from these tribes gave to themselves long before Lewis and Clark and other

explorers arrived. It is common for Lakota tribes and tribal members to refer to themselves

and their tribes with their traditional name, Lakota, rather than their federal name, Sioux. The

seven bands, organized by the reservation where they reside, include:

Cheyenne River Indian Reservation

1. Mnicoujou - Plants by the Water

2. Oo’henumpa - Two Kettle

3. Itazipco - No Bows

4. Sihasapa - Blackfoot

Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

5. Oglala - Scatters Their Own

Rosebud Indian Reservation

6. Sicangu - Burnt Thighs

Tipis were original dwellings of Native Americans of the Great

Standing Rock Indian Reservation Plains. Today, tipis are set up during special events or at lodging

establishments for visitors to stay.

7. Hunkpapa - Camps at the Entrance

What is the history of the dispute over ownership of the Black Hills?

Encroachment by miners and settlers into the Black Hills region precipitated the Red Cloud

Wars in the 1860s. Indian people lost most of these skirmishes, and the result was the Fort

Laramie Treaty of 1868. This treaty placed the Lakota people on the Great Sioux Reservation.

In 1889, after gold was discovered in the Black Hills, the federal government confiscated 7.7

million acres of what had been awarded to tribes in the sacred Black Hills. In 1921, Sioux

tribes filed the lawsuit claiming that the Hills were taken illegally. The lawsuit took 60 years to

reach the US Supreme Court. On July 23, 1980, the Supreme Court decreed that the Hills were

taken illegally and did belong to the tribes of the Sioux Nation. The Court awarded the tribes

$105,994,430.52 for the Black Hills (Docket 74B) and $40,245,807.02 for lands taken east

of the Black Hills (Docket 74A). Justice Harry Blackmun in his legal opinion wrote, “A more

ripe and rank case of dishonest dealings may never be found in our history.” To this day, area

tribes have refused to accept this settlement money as a matter of principle. With interest, the

value of the money awarded is approaching $1 billion.

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Discover the Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge

and Rosebud Reservations

T O U R S

What will I discover as I travel through the Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge

or Rosebud Reservations?

The Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, and Rosebud Reservations are huge—each one covers

an area about the size of the state of Connecticut. The three reservations have unique

characteristics but all of them share unique prairie

grasslands and miles of open space watched over by

hawks, pheasants, and many other birds. In some places,

you can drive for miles with only nature and wildlife as

company. The stark, solitary beauty of the prairie will

amaze you. There are farms and ranches with cattle,

horses, and buffalo. Buffalo (Tatanka) hold great spiritual

significance for the Lakota people. The magnificent

Wild horses graze among the beautiful Badlands on the Pine

Ridge Reservation. Approximately 120,000 acres of the

animal gave itself to provide food, clothing and shelter

Reservation are in the Badlands, which adjoins Badlands for the people.

National Park.

Who will I meet?

The Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, and Rosebud

Reservations are home to people from many different

ethnicities. Many families have lived on these reservations

for multiple generations. They come from all walks of life

and hold jobs that are common to any rural community

in South Dakota. Most people are familiar with the whole

reservation area and can guide you to your next stop. They

share a heritage as old and wondrous as the area you pass

through. Dress is usually casual and cowboy boots and Businesses located in the reservation communities offer a

hats are common. variety of products and services to their customers. Rebecca

LaPlante co-owns a sporting goods store with her brothers

in Eagle Butte, on the Cheyenne River Reservation.

What are the road and housing conditions?

Expect to find well maintained, paved roads leading to the main communities on these

reservations. But like many rural areas, expect gravel roads when you head out to more

remote locations. Poverty remains a challenge on all of South Dakota’s reservations. Housing

conditions are often substandard. Multiple years of drought conditions are making it difficult

to sustain the agricultural way of life that drives the economies of the Cheyenne River, Pine

Ridge, and Rosebud Reservations.

When is the best time to visit?

Each season brings time honored traditions to the reservations. In the summer, there are regular

rodeos and pow wows (wacipis) where local people and visitors gather together under a tent

or under the open skies to cheer on traditional dancers and drummers wearing fancy regalia

or to celebrate the bull rider who stays on the longest. In the fall there are hunting and fishing

opportunities. Like the rest of South Dakota, summers are often hot, falls and springs are cool,

and winters are cold.

continued on back

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Where can people hunt or fish?

These reservations contain both trust and non-trust lands. Hunting T O U R S

and fishing regulation on trust lands (tribal and allotted lands) falls

under the jurisdiction of the each Tribe’s Game, Fish, and Parks

Department, whereas, hunting and fishing on non-trust lands—state, private, fee, and deeded

lands for nonmembers of the Tribe, falls under jurisdiction of the South Dakota Department of

Game, Fish, and Parks. As with hunting private lands, permission must be granted first for all

non-members hunting on tribal lands. Depending on the reservation and the season of the year,

guided hunts are available for a wide array of animals—elk, deer, turkey, prairie dog, pheasant,

buffalo, and more.

What services can visitors expect to find on the

Reservation?

Visitors will find small motels, B&Bs, and campgrounds.

Call well in advance to make sure there is a room available.

There are gas stations, grocery stores, restaurants, and ATM

machines. There are hardware and clothing stores, and other

Lakota Prairie Ranch Resort, on the Pine Ridge

Reservation, is just one of the many businesses that

shops. Not every business will accept credit cards. There are

caters to visitors. healthcare services for emergencies and mechanics who fix

cars. Visitors will find a place to view and purchase locally made artwork including paintings,

beadwork, star quilts, drums, and more. Information about services for visitors and how to find

local artists and their works is available at NativeDiscovery.org.

What are the populations of the Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, and

Rosebud Reservations?

Based on the 2000 US Census data (numbers that are often disputed because they don’t

reflect population counts done by other agencies including the Bureau of Indian Affairs),

the Cheyenne River Reservation has a population of approximately 9,600 individuals, with

approximately 6,000 of them being Native American. The 2000 Census states that Pine Ridge

Reservation has a population of approximately 23,000 individuals, with approximate 14,000

of them being Native American. And Census numbers for the Rosebud Reservation has a

population of approximately 10,500 individuals, with 9,000 of them being Native American.

Not captured in these census figures are estimates of how much population numbers can

change depending on the season. For example, Pine Ridge estimates that depending on the

season, as many as 30,000 people live on the reservation. According to the US Census Bureau,

there are approximately 70,000 American Indian or Alaska Natives living in South Dakota—

about 9% of the total population.

What is the Native American Scenic Byway?

The National Scenic Byways Program is part of the U.S. Department of Transportation,

Federal Highway Administration. The program is a collaborative effort established to help

recognize, preserve and enhance selected roads throughout the United States. The Native

American Scenic Byway includes 305 miles that are nationally designated, and approximately

150 additional miles that are state designated. The Byway stretches into four reservations—the

Crow Creek, Lower Brule, Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock and through Yankton Tribal

Lands. It includes picturesque landscapes of plains, farmland, rolling hills, and rivers.

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Sacred Number Four and the

Medicine Wheel T O U R S

Number Four

The number four is a sacred number for the Lakota people. There are four directions—north,

south, east, and west; four elements—earth, fire, air, and water; four seasons—winter, spring,

summer, and fall; and four races—red, black, white, and yellow. And there are four core

values:

1. Generosity (Wacantognaka) – Giving from the heart. Lakota people value generosity and

a man is honored for what he gives to the People. Remembering this exchange, everyone is

cared for and thrives, not just the “one”.

2. Courage (Woohitika) - Being brave. Lakota people are taught by example how to have great

courage. They learn it is an honor to face hard and difficult things yet maintain a quiet strength

and enduring sense of humor.

3. Respect (Waohola) - Respecting somebody. People should have respect for each other (the

two-leggeds), and the four-leggeds, the winged ones, the stone people, the sky and Unci Maka

(Grandmother Earth). Lakota people believe that people should have respect for one another.

We can never forget that we are all related.

4. Wisdom (Woksape) – Sharing wisdom. Elders are looked up to and respected for their

knowledge and wisdom. Sharing this knowledge through storytelling honors the oral tradition

of the Lakota people and guides the generations to come.

The Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations are made up of

beautiful landscapes of rolling prairies and grasslands, canyons and valleys.

continued on back

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

T O U R S

Medicine Wheel

The medicine wheel is a symbol of health and well being.

The wheel symbolizes the continuing cycle of life from birth

to death—movement in a circle has a beginning and an end,

and yet is never ending. The spokes of the wheel are remind-

ers of the four directions. Each of the four directions has a

color associated with it and a prayer is said to each direction.

South = White (White-Winged Animals)

White symbolizes the Great Spirit, Creator, and provider of

all things (Tunkasila). White symbolizes the Creator’s purity

from which came the purification ceremonies, especially

the Sun Dance, sweat lodge, and fasting. The prayer to the south is: “Tunkasila, we need your

strength to heal us and the earthy, to be our friend every day. We will be patient and wait for

your sign. Thank you, Tunkasila.”

North = Red (Buffalo Nation)

Red symbolizes the Great Spirit in the rising sun of light and life. A new day is born to sing the

praises of the Great Spirit. The special prayer said to the north is: “As we pray for you to see

and hear, lead us Tunkasila and shield us from evil spirits. Thank you Tunkasila for all of the

benefits of your guiding hand. We are lost without you.”

East = Yellow (Deer Nation)

Yellow symbolizes the Great Spirit as the provider of all blooming nature for man to use, mul-

tiply, and store for future use. The Great Spirit expects man to share his good fortune and to

give verbal thanks and sacrifice in thanksgiving. The special prayer for the east is: “Tunkasila,

guide us in the harvest so that we do not destroy your gifts, nor be wasteful, but be conscious

of the needs of our fellow man at all times.”

West = Black (Horse and Dog Nation)

Black symbolizes the Great Spirit in the setting sun of light and life. Man should be conscious

of time passing and ending. He should review each day and its blessings and ask Tunkasila to

guard him through another day. The special prayer for the west is: “As darkness overcomes us,

we pray in thanksgiving for all the blessings given us from the bounty of your love Tunkasila.”

* The prayers above are examples. Prayers vary by reservation.

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Traditional Lakota Art

T O U R S

Beauty and art have played a large role in the day-to-day lives of Lakota people for millennia.

Designs that focused on originality, harmony, emotional and aesthetic impact, symbolism, and

skill have been found in and around the homes of Lakota from before Western contact up to

the present day. That creativity and blurring of the line between art and every day can be seen

today in art forms from beadwork and quillwork to woodcarvings and star quilts.

Star quilts by Bonnie LeBeau, Cheyenne Acrylic paintings by Richard Red Owl, Pine Paintings and batik by Linda Szabo, Rosebud

River Reservation Ridge Reservation Reservation

The earliest forms of traditional arts were painted designs on parfleche—folded containers

made from the hide of large animals—and the use of dyed and wrapped or tacked porcupine

quills on many items such as clothing and ceremonial objects. These techniques and styles can

still be seen today and are often passed along within families from generation to generation.

Today, quillwork is seen as earrings and other jewelry, on pipe bags, moccasins, dance regalia,

and many other places.

Beadwork is most often associated with the Lakota and other Native American groups, but is a

more recent media that Lakota artists have embraced and made their own. Beads were intro-

duced to the Northern Plains in the 19th century, and many of the techniques and patterns used

in quillwork were modified for use in beading items ranging from ceremonial to utilitarian.

Color combinations and preferences have changed constantly over the years, but many fami-

lies still use the same patterns that have been used for centuries. Modern styles, markets, and

trends have expanded the use of the beadwork to items such as watch bands, key chains, bar-

rettes, jewelry, clothing and footware, quilts and blankets, carvings and sculptures, drum and

dance regalia, prints and paintings, weapons, home décor, and baby gifts.

Another more modern form of Lakota art is the star quilt, which incorporates traditional ideas

of color and design along with the functionality of a usable blanket. Learning from the Amish

while attending boarding schools in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Lakota women brought

the star quilt back to the reservations and it became an outlet for traditional artistic values.

Today star quilts are a vital part of the modern Lakota culture and are a vibrant art form.

Native American art is packed with history and breathtaking beauty. We invite you to discover

the wondrous heritage of the Lakota people through their art.

As part of the Native Discovery partnership, artists from the Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, and

Rosebud Reservations are featured at NativeDiscovery.org. Check out the website to meet the

artists and view some of their work they have for sale.

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Recommended Books

T O U R S

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West by Dee Brown.

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1970.

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee focuses on events taking place from 1860 to 1890 and

provides an account of the time period told from the Native American point of view. It

combines several eyewitness accounts and official records and presents a critical indictment

of the US politicians, soldiers, and citizens who colonized the American West. The author

demonstrates that white people instigated the great majority of the conflicts with Native

Americans. The book describes the US government’s attempt to acquire land from Native

Americans by using a mix of threats, deception, and murder. In addition, the book showed

the attempts to crush Native beliefs and practices. These acts were justified by the theory of

Manifest Destiny, which stated that European descendents acting for the US government had a

God-given right to take land from the Native Americans.

Waterlily by Ella Cara Deloria. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

Ella Cara Deloria was born in 1889 on the Yankton Reservation and lived as a child on the

Standing Rock Reservation. Her novel depicts both the everyday activities and extraordinary

events of female Dakota (Sioux) in the mid-nineteenth century, before whites settled the plains.

The Nations Within: The Past and Future of American Indian Sovereignty by Deloria Vine Jr.

and Clifford M. Lytle. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984.

This book is on Native American self-rule. It focuses on John Collier’s struggle with both the

US Congress and the Native American tribes to develop a New Deal for Native Americans.

The book provides a detailed historical account and includes current Native American points

of view about initiatives Native people have taken to rebuild their communities. It suggests

that Native Americans might be better and faster if they are allowed to engage in community

rebuilding in their own ways.

The Soul of an Indian and Other Writings from Ohiyesa by Charles Alexander (Ohiyesa)

Eastman and Kent Nerburn. New World Library, 1993.

Ohiyesa is a Dakota Native American born in Minnesota in 1858. He is also known as Charles

Alexander Eastman. He obtained postgraduate degrees and advised US presidents before

returning to traditional living in native forests. This is a sequel to the highly acclaimed Native

American Wisdom and is an exploration of Native American spirituality. Nerburn draws from

several of Ohiyesa’s books, including The Soul of the Indian.

continued on back

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

T O U R S

The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living by Joseph M. Marshall III. New York:

Penguin Compass, 2002.

Joseph Marshall is a member of the Rosebud Lakota Tribe. He focuses on the twelve core

qualities that are crucial to a Lakota way of living—bravery, fortitude, generosity, wisdom,

respect, honor, perseverance, love, humility, sacrifice, truth, and compassion. The Lakota Way

looks at spirituality and ethical living and draws from the wisdom Joseph learned from his

elders to impart the path to a fulfilling and meaningful life.

Neither Wolf Nor Dog: On Forgotten Roads with an Indian Elder by Kent Nerburn. New

World Library, 2002.

Kent Nerburn draws the reader deep into the world of a Lakota elder known only as Dan who

speaks about Native American life of the past and present. The book weaves memories of the

Ghost Dance and Sitting Bull into a world of Native American towns, white roadside cafes,

and abandoned roads. The book features a story of two men struggling to find a common voice

and looks at differences between land and property, the power of silence, and the selling of

sacred ceremonies.

The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America by James Wilson. New York: Grove

Press, 1998.

This book combines traditional historical sources with insights from ethnography, archaeology,

Native American oral tradition, and years of original research to create a history of Native

Americans and the struggle for survival against the tide of invading European peoples

and cultures. The book is divided into three main parts. Part I, “Origins,” deals with the

fundamental differences between Native American origin myths and the Western (white)

man’s belief system, and reviews what little is known of pre-contact Native America. Part II,

“Invasions,” separately covers the history of each major part of the country since contact. Part

III, “Internal Frontiers,” covers the widely differing policies our government has adopted in

the last 150 years to deal with “the Indian problem.”

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Cheyenne River Indian Reservation

T O U R S

The Cheyenne River Indian Reservation—the Good River Reservation (Wakpa Wasté Oyanke)

is located in north central South Dakota. The Reservation is bordered by the Missouri River

on the east and the Cheyenne River on the south. The Reservation encompasses approximately

2.4 million acres, with 1.4 million held by the Tribe. It is an area approximately the size of

the state of Connecticut and includes 14 small, dispersed communities and two counties. It is

bordered by the Missouri River on the east and the Cheyenne River on the south. Highway

212 runs east-west through the Reservation and County Road 63 runs north-south, connecting

the Reservation to Interstate 90. According to the 2000 US Census, the Cheyenne River

Reservation has a population of approximately 9,600 individuals, including about 6,000 Native

Americans.

The official flag of the Cheyenne River Tribe appears below. The blue represents the thunder

clouds above the world, home to the thunder birds that control the four winds. The rainbow is

for the Cheyenne River People who are keepers of the most sacred Calf Pipe, a gift from the

White Buffalo Calf Maiden. The eagle feathers at the edges of the rim of the world represent

the spotted eagle who is the protector of all Lakota. The two pipes fused together are for unity.

One pipe is for the Lakota, the other is for other Indian nations. The yellow hoops represent the

Sacred Hoop, which shall not be broken. The Sacred Calf Pipe Bundle in red represents Wakan

Tanka, the Great Mystery. All the colors of the Lakota are visible. The red, yellow, black, and

white represent the four major races.

Cheyenne River Reservation

SOUTH DAKOTA

29

Eagle Butte, SD

212

83

212

63

90

37

83

79 14 63

Badlands

90

40

90

83

44

37

18

18

Rosebud, SD

29

Pine Ridge, SD

Pine Ridge Reservation Rosebud Reservation

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Rosebud Indian Reservation

T O U R S

The Rosebud Indian Reservation is located in south central South Dakota. The Reservation is

bordered by the Pine Ridge Reservation on the northwest corner and by the state of Nebraska

on the south. The largest portion of the Reservation is located in Todd County. There are also

surrounding Tribal Lands located in parts of Tripp, Mellette, Gregory, and Lyman Counties.

This larger tribal land area encompasses a geographic area of approximately 890,000 acres.

Highway 18 runs east-west through the Reservation and Highway 83 runs north-south,

connecting the Reservation to Interstate 90. According to the 2000 US Census, the Rosebud

Reservation has a population of approximately 10,500 individuals, including about 9,000

Native Americans.

The official flag of the Rosebud Tribe appears below. The center and cross in the middle

represents the wisdom of the Lakota people. The diamond represents the four directions of

the Rosebud Reservation. Crossed pipes represent the pipe of peace and friendship to all who

come to the Reservation. Peace pipes are also a spiritual and religious symbol. The 20 roses

with Lakota Tipis inside them represent the 20 communities on the Reservation. The name

Rosebud was designated for the Sicangu Lakota people back in 1877 because of the abundance

of rosebuds that grew in the area.

White represents purity and the North where snow comes from. Red represents the sunrise

and the East. It also indicates sunset, thunder, lightening, and forms of plant and animal life.

Yellow is for the land of sunshine and the South. Blue represents the sky, clouds, wind, moon,

water, day and the West. Black represents night and the mysteries. Orange has no historical

significance—it is a mixture of red and yellow.

Cheyenne River Reservation

SOUTH DAKOTA

29

Eagle Butte, SD

212

83

212

63

90

37

83

79 14 63

Badlands

90

40

90

83

44

37

18

18

Rosebud, SD

29

Pine Ridge, SD

Pine Ridge Reservation Rosebud Reservation

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

T O U R S

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is located in southwestern South Dakota on the Nebraska

state line, about an hour south of Interstate 90 and an hour east of the Black Hills area (Paha

Sapa—the Heart of Everything That Is). The area includes over 11,000 square miles. Most of

the land comprising the reservation lies within Shannon and Jackson Counties. In addition,

there are extensive off-reservation trust lands, mostly in adjacent Bennett County, but also

extending into adjacent Whiteclay, Nebraska in Sheridan County. This larger tribal land area

encompasses a geographic area of approximately 2.2 million acres. Highway 18 runs east-

west through the southern end of the Reservation, County Road 44 runs east-west across the

northern end, and County Roads 73 and 377 run north-south, connecting the Reservation to

Interstate 90. The Reservation borders the Badlands National Park (Maka Sica—land bad) on

the north and 120,000 acres of the Park are part of the Reservation. According to the 2000 US

Census, the Pine Ridge Reservation has a population of approximately 23,000 individuals,

including about 14,000 Native Americans.

The official flag of the Oglala Tribe appears below. The red flag bears a circle of eight white

teepees representing the eight districts of the Pine Ridge Reservation. The districts include

Porcupine, Wakpamni, Medicine Root, Pass Creek, Eagle Nest, White Clay, LaCreek, and

Wounded Knee. The red color represents the Lakota people and is considered a sacred color.

Cheyenne River Reservation

SOUTH DAKOTA

29

Eagle Butte, SD

212

83

212

63

90

37

83

79 14 63

Badlands

90

40

90

83

44

37

18

18

Rosebud, SD

29

Pine Ridge, SD

Pine Ridge Reservation Rosebud Reservation

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

T O U R S

Are You Welcome to Visit Tribal Communities and Reservations?

Absolutely! We have been welcoming visitors - Indian and non-Indian – to our communities since

the beginning of time. When visiting, please treat our home as you would anyone else’s – with respect

for property, privacy and traditions. Here are a few suggestions to help you navigate.

• Not all ceremonies and performances are open to the general public. Public events will be

announced.

• Observe ceremonies and performances respectfully.

• Ask permission before taking photographs or making recordings or sketches.

• Supervise your children at all times.

• Observe signs and stay in designated areas.

• Homes are private. Enter only when invited.

• Leave undisturbed any objects or artifacts, including fossils, that you may find on the ground.

• Alcohol, weapons and drugs are prohibited at tribal events.

• Obey all posted rules and laws.

• When uncertain, simply ask!

It’s common sense, really.

So enjoy your visit and come back again and again.

Is It Indian-Made?

As you visit tribal communities you’ll see an amazing array of traditional and contemporary art

– from painting and sculpture to beautiful textiles, beadwork, jewelry, quillwork, quilts and more. Our

arts are distinct, and our artists are respected and valued.

If you would like to purchase a work of art, please observe the following suggestions to ensure that

what you’re about to purchase is authentically produced by American Indian artists.

• Know what you are buying.

• Buy only from reputable sources and places.

• Ask for documentation such as a receipt that describes what you’ve purchased and identifies the

artist.

• Whenever possible, buy directly from the artist.

• Know the artist’s name and tribal affiliation, and be sure each piece is signed or hallmarked (a

logo or symbol that represents that specific artist). This is recommended for insurance purposes

and will help document your trip and/or collection.

• Not all artists will bargain over price. This is a case-by-case situation.

If artworks are marketed as “American Indian,” they must be made by an enrolled member of a

federally or state recognized tribe. If not, it is a violation of the federal Indian Arts and Crafts Act of

1990 which was enacted to curtail exploitation of tribal artists and art forms.

For more information, please contact the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (IACB), Department of the

Interior, Washington, DC, at (202) 208-3773 or visit www.doi.gov/iach/

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

T O U R S

Do All Tribes Operate Casinos?

There are 562 federally recognized tribes in the United States today. Of these, two in five tribes

have gaming operations. To learn more about tribal casinos, visit the National Indian Gaming

Association’s website at www.indiangaming.org. You’ll discover that tribal casinos are just as

different from one another as the tribes themselves.

In most cases, casinos help tribes rise above the economic poverty many of our communities

have known for generations. They provide jobs and services that are often rare in tribal

communities. Revenues generated by casinos are dedicated to improving tribal education, health

care, housing, natural and cultural resources, language, culture, infrastructure and government.

Local, non-tribal communities benefit, too, in the form of jobs, financial support for essential

governmental services and charitable contributions to schools, libraries and other non-profit

organizations.

Used with permission from COTA (Circle of Tribal Advisors) and the Missouri Historical Society.

Copyright © Native Discovery 2007

You might also like

- 2018 Treaty RightsDocument60 pages2018 Treaty RightsDawn AnaangoonsiikweNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Guide to Butchering Deer: A Step-by-Step Guide to Field Dressing, Skinning, Aging, and Butchering DeerFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide to Butchering Deer: A Step-by-Step Guide to Field Dressing, Skinning, Aging, and Butchering DeerRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A PDF of Instructions From The Book To Make Sabines Purple Rope Necklace.Document10 pagesA PDF of Instructions From The Book To Make Sabines Purple Rope Necklace.vddidabijoux71% (17)

- Men's and Women's 1600s Shirts and ShiftsDocument13 pagesMen's and Women's 1600s Shirts and ShiftsDean Willis100% (4)

- Chubby Frogs 2021 - English - Rin - Meow21Document8 pagesChubby Frogs 2021 - English - Rin - Meow21Le Thi Thanh Van100% (1)

- Inuit MythologyDocument129 pagesInuit MythologyJOSEPH100% (18)

- Gabby: Ginansilyo - Ni - MaryaDocument15 pagesGabby: Ginansilyo - Ni - MaryaPedro Cordeiro da Natividade100% (3)

- Purse vintageTVDocument8 pagesPurse vintageTVSil100% (1)

- Chippewa Chiefs' 1849 Petition to Preserve Wisconsin HomelandDocument54 pagesChippewa Chiefs' 1849 Petition to Preserve Wisconsin Homelandnative112472No ratings yet

- Canadas First PeopleDocument16 pagesCanadas First Peopleapi-256261063100% (1)

- 12 Awesome Free Quilt Patterns and Small Quilted ProjectsDocument91 pages12 Awesome Free Quilt Patterns and Small Quilted ProjectsLisa100% (2)

- The Sioux: The Past and Present of the Dakota, Lakota, and NakotaFrom EverandThe Sioux: The Past and Present of the Dakota, Lakota, and NakotaNo ratings yet

- History of the Dakota or Sioux IndiansDocument436 pagesHistory of the Dakota or Sioux IndiansTsistsisNo ratings yet

- Carlitos RugratsDocument17 pagesCarlitos RugratsSANDRA LOPEZ RAMIREZ100% (2)

- Final Examination in Contemporary Philippine ArtsDocument2 pagesFinal Examination in Contemporary Philippine ArtsApril Ann Diwa AbadillaNo ratings yet

- Crochet Hello Kitty PatternDocument5 pagesCrochet Hello Kitty PatternAYLIN caraveoNo ratings yet

- Crochet Captain America PDF Amigurum PatternDocument9 pagesCrochet Captain America PDF Amigurum PatternDayana AraujoNo ratings yet

- Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern CityFrom EverandSeven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern CityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (81)

- AchomawiDocument7 pagesAchomawiGiorgio MattaNo ratings yet

- Northwest Power and Conservation Council's Tribal DirectoryDocument62 pagesNorthwest Power and Conservation Council's Tribal Directorysprig_jack3706No ratings yet

- Néhinaw Néhiyaw: Sub-Groups / Geography Political Aboriginal OrganizationDocument22 pagesNéhinaw Néhiyaw: Sub-Groups / Geography Political Aboriginal OrganizationAYESHA NAAZNo ratings yet

- Sailor Warriors Mini Amigurumi PatternDocument19 pagesSailor Warriors Mini Amigurumi Patternjosselin martinez100% (4)

- Wire Wrapping ProjectsDocument20 pagesWire Wrapping Projectsodile lambNo ratings yet

- Edge Lace 2.3: Picture 1Document2 pagesEdge Lace 2.3: Picture 1Josefina Fuentes100% (1)

- Sioux IndiansDocument4 pagesSioux Indiansmetookool100% (1)

- Chief Left Hand, by Margaret CoelDocument413 pagesChief Left Hand, by Margaret CoelСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- The Grizzly Bear in Cheyenne Religion, by Winfield ColemanDocument15 pagesThe Grizzly Bear in Cheyenne Religion, by Winfield ColemanСтепан Васильев50% (2)

- How To Crochet A Daisy Granny SquareDocument7 pagesHow To Crochet A Daisy Granny SquareAnnaNo ratings yet

- SFAA Catalog 2020Document180 pagesSFAA Catalog 2020Степан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- First Americans 2Document31 pagesFirst Americans 2Juan Miguel Reyes100% (1)

- Voices of the PeopleFrom EverandVoices of the PeopleNo ratings yet

- Alfa 472 Sewing Machine ManualDocument44 pagesAlfa 472 Sewing Machine ManualFrancis Gladstone-Quintuplet100% (1)

- Solid Materials: Accessories, Footwear & JewelleryDocument20 pagesSolid Materials: Accessories, Footwear & JewelleryRaquel MantovaniNo ratings yet

- Lone Horn's Peace - Crow-Sioux Relations, by Kingsley BrayDocument21 pagesLone Horn's Peace - Crow-Sioux Relations, by Kingsley BrayСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- PoliKnittedToys - Fidget Sensory Stretchable Toy - OwlDocument18 pagesPoliKnittedToys - Fidget Sensory Stretchable Toy - OwlRuth Farias Henriquez100% (1)

- Margotthe Cat Crochet PatternDocument12 pagesMargotthe Cat Crochet Patternnatalie cortezNo ratings yet

- Easy Crochet AngelDocument11 pagesEasy Crochet AngelElena NitulescuNo ratings yet

- Lakota Drum, "Rhythm of The Heart": InstrumentDocument6 pagesLakota Drum, "Rhythm of The Heart": InstrumentPam NoctisBlackNo ratings yet

- Sioux Native Americans Their History, Culture, and TraditionsDocument1 pageSioux Native Americans Their History, Culture, and Traditionschloemurer11No ratings yet

- Missouri River Recovery Committee GuideDocument2 pagesMissouri River Recovery Committee GuideMary RothNo ratings yet

- September 2006 Peligram Newsletter Pelican Island Audubon SocietyDocument4 pagesSeptember 2006 Peligram Newsletter Pelican Island Audubon SocietyPelican Island Audubon SocietyNo ratings yet

- Sand-Trapped History: Uncovering The History of Sleeping Bear Dunes National LakeshoreDocument20 pagesSand-Trapped History: Uncovering The History of Sleeping Bear Dunes National LakeshoreMarie CuratoloNo ratings yet

- Sioux People: History, Culture and Current ChallengesDocument2 pagesSioux People: History, Culture and Current Challengesremy shanleyNo ratings yet

- The Sioux People: A Concise History of the Indigenous TribeDocument10 pagesThe Sioux People: A Concise History of the Indigenous TribeBlajvatoreNo ratings yet

- Bears Ears: Landscape of Refuge and ResistanceFrom EverandBears Ears: Landscape of Refuge and ResistanceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Pokagon Indiana State Park: Indiana State Park Travel Guide Series, #5From EverandPokagon Indiana State Park: Indiana State Park Travel Guide Series, #5No ratings yet

- Field Museum of Nat 48 ChicDocument32 pagesField Museum of Nat 48 Chicacademo misirNo ratings yet

- The Siouan Indians by McGee, W. J. (William John), 1853-1912Document48 pagesThe Siouan Indians by McGee, W. J. (William John), 1853-1912Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Chi4u NotesDocument11 pagesChi4u NotesFatima-Zahra Kamal KajjiNo ratings yet

- March 2008 Gambel's Tales Newsletter Sonoran Audubon SocietyDocument10 pagesMarch 2008 Gambel's Tales Newsletter Sonoran Audubon SocietySonoranNo ratings yet

- Course Project 2600Document7 pagesCourse Project 2600api-242792496No ratings yet

- 1993 Utah Native Plant Society Annual CompliationsDocument63 pages1993 Utah Native Plant Society Annual CompliationsFriends of Utah Native Plant SocietyNo ratings yet

- "Wolf Wars in The Southwest " "Bald Eagles of Northern Arizona"Document8 pages"Wolf Wars in The Southwest " "Bald Eagles of Northern Arizona"PrescottNo ratings yet

- The Plains.: By: Gio, Kirit, Safa, Darrin and BrodyDocument11 pagesThe Plains.: By: Gio, Kirit, Safa, Darrin and BrodydonNo ratings yet

- M is for Minnesota: Written by Kids for KidsFrom EverandM is for Minnesota: Written by Kids for KidsNo ratings yet

- CRCT Summary Sheets For Science and Social Studies W1qio2Document34 pagesCRCT Summary Sheets For Science and Social Studies W1qio2api-263393933No ratings yet

- SiouxDocument10 pagesSiouxapi-318983933No ratings yet

- Native Americans 3-2 1Document11 pagesNative Americans 3-2 1api-248487722No ratings yet

- Ancestral Heritage Ancestral Heritage: Dispatch From The Deadliest Warrior' On Desert DeploymentDocument9 pagesAncestral Heritage Ancestral Heritage: Dispatch From The Deadliest Warrior' On Desert DeploymentChetanya MundachaliNo ratings yet

- March 2006 Gambel's Tales Newsletter Sonoran Audubon SocietyDocument10 pagesMarch 2006 Gambel's Tales Newsletter Sonoran Audubon SocietySonoranNo ratings yet

- Rosebud Winter Count, by Russell ThorntonDocument18 pagesRosebud Winter Count, by Russell ThorntonСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Black Moon - The Minnecoujou Leader, by Ephriam DicksonDocument2 pagesBlack Moon - The Minnecoujou Leader, by Ephriam DicksonСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- The Battle of Arickaree, by Winfield FreemanDocument9 pagesThe Battle of Arickaree, by Winfield FreemanСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Northern Plains and Woodland Indians Individual Star Names and Traditions, by Herman E. BenderDocument72 pagesNorthern Plains and Woodland Indians Individual Star Names and Traditions, by Herman E. BenderСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Making Medicine Against White Man's Side of Story, by Lincoln FallerDocument69 pagesMaking Medicine Against White Man's Side of Story, by Lincoln FallerСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Wind Through The Buffalo Grass - A Lakota Story Cicle, by Paul JohnsgardDocument241 pagesWind Through The Buffalo Grass - A Lakota Story Cicle, by Paul JohnsgardСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- The People of Bear Hunter Speak, by Aaron Crawford PDFDocument98 pagesThe People of Bear Hunter Speak, by Aaron Crawford PDFСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Captain John R. Bell 1820Document46 pagesThe Journal of Captain John R. Bell 1820Степан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Sacred Black Hills Sites and Indigenous ControversyDocument55 pagesSacred Black Hills Sites and Indigenous ControversyСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Dakota Winter Counts As A Source of Plains History, by James HowardDocument88 pagesDakota Winter Counts As A Source of Plains History, by James HowardСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Indian Maps Their Place in The History of Plains Cartography, by G. Malcolm LewisDocument19 pagesIndian Maps Their Place in The History of Plains Cartography, by G. Malcolm LewisСтепан ВасильевNo ratings yet

- Jeffers Petroglyphs, by Tom SandersDocument52 pagesJeffers Petroglyphs, by Tom SandersСтепан Васильев100% (1)

- Durene Jones MR Arctic Fox ChartDocument6 pagesDurene Jones MR Arctic Fox Chartjoanna sNo ratings yet

- Amiimaker Giraffe PatternDocument8 pagesAmiimaker Giraffe PatternclauditamarNo ratings yet

- ChecklistDocument5 pagesChecklistapi-535090590No ratings yet

- Little CowDocument13 pagesLittle Cowanetamajkut173No ratings yet

- 1. Materials 2. Design 3. Name of project 4. Objectives 5. ProcedureB. Unscramble the jumbled letters to reveal the materials needed.1. cplwioas2. btael cloth 3. hbt wtole4. dnha wetol5. pmalectDocument7 pages1. Materials 2. Design 3. Name of project 4. Objectives 5. ProcedureB. Unscramble the jumbled letters to reveal the materials needed.1. cplwioas2. btael cloth 3. hbt wtole4. dnha wetol5. pmalectMa Junnicca MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- Objectives: Passion Awareness AppreciationDocument14 pagesObjectives: Passion Awareness AppreciationElisha TanNo ratings yet

- Baby Bunnies Barnevognskde enDocument10 pagesBaby Bunnies Barnevognskde enMCbotelhoNo ratings yet

- Fabric Chart Young 3EDocument10 pagesFabric Chart Young 3EPuja PrasadNo ratings yet

- Lalimalu 1111 Collection - IG StoryDocument15 pagesLalimalu 1111 Collection - IG StoryAmy FauziNo ratings yet

- Virgin of the Immaculate Conception Tin-glazed Object from 1798Document5 pagesVirgin of the Immaculate Conception Tin-glazed Object from 1798Juan Garcia TausteNo ratings yet

- Sonajero OsosDocument3 pagesSonajero OsosLola DeYeyoNo ratings yet