Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

Uploaded by

Catarina GrandeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

Uploaded by

Catarina GrandeCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Education and Educational Development Article

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools:

Teacher Perceptions

Itfaq Khaliq Khan 1

Sightsavers

Itfaq.pmac@gmail.com

ShujahatHaider Hashmi 2

Capital University of Science and Technology

shujahat_hashmi@hotmail.com

Nabeela Khanum3

Independent Research Scholar

khanum.nabila@gmail.com

Abstract

The perceptions of primary school teachers towards inclusive

education was investigated in mainstream government schools of

Islamabad capital territory where inclusive education was being

supported by Sight savers and other international organizations. The

study was carried out involving 54 teachers in six randomly selected

primary schools. The sampled group comprised both, teachers trained

in inclusive education and teachers working in same schools, but

not trained in inclusive education. Purposive sampling method was

used to select the teachers. Structured questionnaire (Likert Scale)

and structured interview method was used for data collection. The

results of the study revealed that inclusive education is considered

to be a desirable practice. The teachers believed that all learners

regardless of their disabilities should be in regular classrooms and

32 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

they showed more favorable attitude towards children with mild

disabilities, but were not very optimistic about children with severe

disabilities. The study also recognized teachers’ capacity as an

essential component of inclusive education and recommends that

inclusive education should be a part of pre and in-service teacher

education.

Keywords: children with disabilities, government schools,

inclusion, inclusive education

Introduction

Sixty seven million children of primary school age are out

of schools; of which one third live in South Asia and Sub Saharan

Africa where Children with Disabilities (CWDs) make one third

out of school children (UNESCO, 2009). Over 90% of CWDs

in developing countries are not able to access schools (Tahir &

Khan, 2010) and only 50% of them enrolled can reach high school

(Belchor, 1995).Pakistan has 5.5 million out-of school children

which is highest in the world after Nigeria (UNICEF & UNESCO,

2014). Situation of CWDs in Pakistan is not different from the

rest of the developing countries. Article 25 of the constitution of

Pakistan and National Education Policy (2009) endorse the right of

every child to free primary education. National Education Policy

(2009) further encourages child friendly and inclusive education.

Nevertheless, majority of CWDs are out of school as there are a very

limited number of special education schools in the country. Ghouri,

Abrar and Baloch, (2010) and UNICEF (2003) have concluded that

teachers in Pakistan have a favorable attitude towards inclusion of

CWDs in the mainstream education system.

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 33

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

Literature review

CWDs face a severe discrimination and exclusion from

education system which affects them in different ways. A number

of initiatives have been taken by global community to recognize

education as a fundamental human right of every child. United

Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), United

Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989) and

United Nations Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities

(UNCRPD, 2006) recognize education as a basic human right

of everyone including CWDs. Article 23 of UNCRC (1989) is

specifically concerned with PWDs, recognizing that they are the

most vulnerable group that face different kinds of discrimination.

Articles 28 and 29 cover the right to education and urge state parties

to ensure that every child has an access to free and quality primary

education on equal basis without discrimination. Article 24 of the

UNCRPD (2006) specifically protects the right of CWDs to the

education without any discrimination and urges state parties to

ensure inclusion of CWDs in the mainstream education system.

Inclusive education is the process of responding to the

diversity of children through enhancing participation in classrooms

and reducing exclusion from education (UNESCO 2007). The

education system which addresses the needs of all children including

CWDs in mainstream schools is termed as Inclusive Education

System. According to Khan, Ahmed and Ghaznavi (2012), inclusive

education expresses the obligation to provide every child with

quality education in mainstream schools, to the maximum extent

possible. An inclusive education system allows carrying educational

34 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Khan, Hashmi, Khanum

services to the child, rather than carrying the child to the educational

services. This system of education focuses upon children who are

enrolled in schools, but are excluded from learning; who are out

of schools, but can be educated if schools are accessible. These

are children with severe disabilities, with specific learning needs

and require a specialized environment. Inclusive education canbe

successful if a child friendly and accessible learning environment

is provided to all children to ensure their inclusion in mainstream

education system.

It has been more than a decade now that inclusive education

is being promoted in both developed and developing countries, but

there are a number of barriers confronting full participation of all

children particularly CWDs. According to UNESCO (2009), lack

of relevant policy support, discriminatory attitude towards CWDs

and neglect of their right to education are the major challenges

confronting their right to access schools. Fernando, Yasmin, Minto

and Khan (2010) conclude that inaccessible school infrastructure;

limited learning materials, limited capacity of teachers, poverty,

disability, conflict and a lack of supporting policy frameworks are the

major causes of exclusion of CWDs from the mainstream education

system. McDonnell and Hardman (1989) state that everyone in

the school has a role to play, but teachers are the most important

players in the provision of inclusive education. Ghouri, Abrar and

Baloach(2010) also recognize teachers’ reluctance to educate CWDs

as a barrier to inclusive education.

It is the responsibility of the teachers to meet the needs of

all learners in classrooms regardless of their abilities or disabilities

(Forlin& Cole, 1993). Hsien (2007) suggests teacher preparation

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 35

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

for inclusive education is important for building confidence and

developing positive attitude towards inclusion of CWDs. Teachers

in ordinary schools are willing to offer their services for inclusive

education, provided they are facilitated with proper training (Garner,

1996, 2000; Rose, 2001; UNICEF 2003). Pinhas and Schmelk in

(1989) confirm that teachers cannot ensure inclusion of CWDs

without support from head teachers. Bailey and Du Plessis (1997)

endorse that the majority of the teachers in mainstream schools hold

positive attitude towards inclusion of CWDs in regular classrooms.

Fakolade (2009) subscribes to the idea that professionally qualified

teachers havemore favorable attitude towards the inclusion of

CWDs. According to LeRoyand Simpson (1996), teachers feel more

confident when they spend time with CWDs. Zenija (2011) alleges

that most teachers are confident that inclusion of children with

special needs is possible to achieve. The study findings of Lambe

and Bones (2006) show that pre-service teacher training is the most

suitable point of intervention to build up teachers’ attitude towards

inclusion of CWDs in regular class rooms. Romiand Leyser (1996)

conclude that positive teacher attitude towards mainstreaming of

CWDs are influenced by numerous factors, such as, policies on

inclusion, school culture and availability of resources to satisfy

the needs of CWDs. The attitude of mainstream teachers toward

inclusive education is considerably influenced by their own levels

of efficiency (Florian, 1998).

Payne and Murray (1974) have confirmed that teachers accept

children with physical, visual, hearing and learning disabilities more

than that of children with mental retardation or severe disabilities.

Rose (2001) urges to build capacity and positive attitude of teachers

towards inclusive education.Attitudes of teachers towards CWDs

36 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Khan, Hashmi, Khanum

are therefore very important for inclusive education; however,

Fakolade (2009) believes that attitude of the teachers and educators

are very complex to measure.

Minimal studies have been carried out in Pakistan on

this important topic. The current study is therefore designed

and carried out to find out the viewpoints of mainstream school

teachers about inclusive education. The study was carried out in

selected schools of Islamabad Capital Territory, where inclusive

education was implemented with the support of Sight savers which

is an international non-governmental organization that works with

partners in developing countries to promote equality for people with

visual impairments and other disabilities.

Methodology

Permission was obtained from Federal Directorate of Education

(FDE) in Islamabad to conduct the study in 12 schools managed by

them. FDE issued a directive to all schools to participate in the study

to facilitate the researcher. These twelve schools were selected for the

study because they were declared as Inclusive Schools by FDE and

there were greater chances that all teachers would have interaction

with CWDs. A descriptive method was followed to collect the data

as the variables of the study were examined in natural settings. The

study was based on two approaches: (a) selection of sampling points,

and (b) data collection from pre-determined survey points through

questionnaire and focus group discussions by the researcher during

data collection.

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 37

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

Participants

The target population for this study was 54 teachers: 12 trained in

inclusive education practices and 42 having a short orientation of

inclusive education practices. All participants of the study were

female teachers having an experience of interacting with CWDs.

Six schools were randomly selected as a sample for the study. This

sampling technique was used because it provides equal opportunity

to all members of the population to be selected. It also helps to

generalize the results of the study on overall population. At the

second stage, purposive sampling technique was applied to select

the teachers.

Instruments

A self-developed Likert Scale questionnaire was constructed called

Viewpoint about Inclusive Education (VPIE). This was validated

by experts, and pilot tested before gathering data from teachers

about inclusive education and mainstreaming of different type of

disabilities. Sixteen items were finalized based on the literature

review, meeting with experts and pilot testing. Each item was

rated on a five point agreement scale from ‘Strongly Agree’ to

‘Strongly Disagree’. 06 focus group discussions were conducted

with the sample group to validate teachers’ responses given through

questionnaires.

Reliability and validity

Survey questionnaires were validated by experts and their suggestions

were incorporated before administering the questionnaires in the

field for data collection. The reliability of all items in questionnaire

38 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Khan, Hashmi, Khanum

was tested using Cronbach Alpha method. All items (α= .802) were

found to be reliable and internally consistent.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis method was used to analyze the data gathered

from teachers through questionnaires using SPSS. All results

including mean, SD and frequency percentages were combined in

one table for convenience. A simple content analysis method was

used to analyze the responses gathered from the teachers through

focus group discussions. Thematic analysis was not conducted

as the purpose was to seek verification of the responses obtained

through VPIE.

Results

The reliability of 16 items was tested using Cronbach Alfa method.

All items of the scale were found to be internally consistent (α=

.802). Descriptive statistical analysis was applied to analyze the

data gathered from teachers through a questionnaire. Frequency

tables and descriptive statistical tables were combined showing

items, mean and frequency percentages for convenience. Responses

of the teachers were also grouped, changing them from scale 05 to

scale 03 combining Agree and Strongly Agree and Disagree and

Strongly Disagree to identify the percentage of respondents actually

agreeing or disagreeing with the statements (see Table 1). The higher

number in the column Agree shows the percent of people supported

the statement, indicating their positive perceptions about inclusive

education.

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 39

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

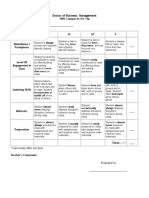

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics of VPIE Scale to Measure Teacher Attitude

towards Inclusive Education

Agree Uncertain Disagree

Item No. Statements Mean SD

(%) (%) (%)

In general, inclusive education

VPIE1 (inclusion) is a desirable Educational 3.81 1.134 74.1 1.9 24.1

practice.

All learners should have the right to be in

VPIE2 3.85 1.035 77.8 5.6 1.9

regular classrooms

It is feasible to teach gifted, normal and

VPIE3 intellectually disabled learners in the 2.52 1.225 33.3 13 52.9

same classroom.

Learners with visual impairments who

VPIE4 can read Standard printed material 2.96 1.288 48.1 9.3 42.6

should be in regular classrooms.

Hearing impaired learners, but not deaf,

VPIE5 3 1.303 51.8 5.6 42.6

should be in regular classrooms

Deaf learners should be in regular

VPIE6 2.24 1.063 20.4 3.7 75.9

classrooms.

Physically disabled learners confined

VPIE7 to wheelchairs should be in regular 3.13 1.15 51.9 13 35.2

classrooms.

Learners with cerebral palsy who cannot

VPIE8 control movement of one or more limbs 2.39 1.172 22.2 16.7 61.1

should be in regular classrooms

Learners with speech difficult to

VPIE9 understand should be in regular 3 1.303 44.5 11.1 44.5

classrooms.

Learners with epilepsy should be in

VPIE10 2.81 1.304 37.1 18.5 44.5

regular classrooms.

Students with Disabilities make

VPIE11 4.09 0.784 89.9 0 11.1

friendships with other students

Other students hoot on Students with

VPIE12 3.41 1.019 63 14.8 22.3

Disabilities due to their disability

You use teaching methods and

VPIE13 3.04 1.243 46.3 14.8 38.9

instructional material suits CWDs

You help Students with Disabilities in

VPIE14 the class when they need extra support 3.98 1.037 79.6 9.3 11.1

from you

You respond to the questions of Students

VPIE15 4.3 0.603 92.6 7.4 0

with disabilities politely

You are happy to teach Student with

VPIE16 3.63 1.248 68.5 13 18.5

Disabilities

40 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Khan, Hashmi, Khanum

The results of the present study conducted through VPIE

and validated by focus group interviews showed that the teachers

favored inclusive education. The majority of the teachers (74%)

agreed that inclusive education is a desirable practice whereas 77%

believed that all learners regardless of their disabilities should be

in regular classrooms. 68% of the sampled group agreed that they

feel very happy to teach CWDs, but at the same time 52% were of

the view that it was not feasible to teach every type of CWDs in

one classroom (items 1, 2 and 3). The study also indicated that the

teachers have a positive perception about children with visual and

hearing impairments and other minor physical disabilities in children.

Around 50% of the sampled group agreed that these children should

be in regular classrooms (items 4, 5 and 7). 75% of the sampled

group believed that deaf learners and 61% believed that learners

with Cerebral Palsy (CP) cannot be accommodated in mainstream

classrooms (items 6 and 8). 44% of the teachers opined that children

with speech difficulty and children with epilepsy should not be

in regular classrooms (items 9 and 10). Item numbers 11 and 12

investigated if inclusive education played a role in social inclusion

of CWDs, for which 90% agreed that CWDs in mainstream school

helps students make friendships with their non-disabled peers;

whereas 63% of the sample also endorsed that CWDs faced hooting

from other children due to their disabilities.

Item 13, 14 and 15 were attempted to know how teachers

dealt with CWDs in the classrooms. The findings showed that the

majority of the teachers (93%) gave CWDs extra time when needed

and 63% responded to their queries politely; whereas, 46% were

able to use teaching and learning aids which were according to the

needs of CWDs.

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 41

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the majority of the

teachers in mainstream schools have positive attitude towards

inclusive education and they are happy to teach CWDs in their

classrooms. They believe that inclusive education is a desirable

practice, which can benefit CWDs and the society and at the same

time they are well aware about the concept of inclusive education

and recognize education as the basic right of CWDs. This is also

confirmed by previous studies (Ghouri, Abrar & Baloch,2010;

UNICEF, 2003), which have determined that the teachers have a

positive attitude towards mainstreaming of CWDs and they are

well aware of the idea and significance of inclusive education, but

teaching all types of CWDs in the same class room was not feasible.

The study also revealed that teachers in mainstream schools

have a more favorable attitude towards children with visual and

hearing impairments and children who are physically disabled (mild

to moderate disabilities) have a less favorable attitude towards

inclusion of children with deafness, cerebral palsy, speech difficult

and epilepsy (severe disabilities). This is similar to the conclusion

drawn by Payne and Murray (1974) that the school staff is inclined

to accept students with physical, visual and hearing impairments

or learning disabilities and they are less inclined to accept children

with mental retardation. This reflects that the teachers are confident

that they can address the educational needs of children with mild

and moderate disabilities and feel that handling children with severe

disabilities in regular classrooms is challenging. One possible

reason of having less favorable attitude towards these children is the

limited capacity of teachers and inaccessibility and unavailability

42 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Khan, Hashmi, Khanum

of assistive technologies. These factors were also highlighted by

teachers during interviews and considered them as major challenges

confronting teachers while dealing with disabilities.

Despite the fact that teachers believe that CWDs face bullying

and hooting by peers without disabilities, inclusive education

enhances opportunities for CWDs to be socially included through

interacting, socializing and making friendships with peers.Inclusive

classrooms are better for CWDs, both academically and socially and

there are greater chances for them to be socially included (Baker,

1995; Bunch &Valeo, 2004; Lipsky & Gartner, 1996).

Though teachers provide CWDs with extra time and deal

with them politely, but they are still not able to address their

educational needs as they have a limited capacity and instructional

material in schools. Rose (2001) has also concluded from her study,

that teachers need training to address the specific needs of CWDs.

Teachers are the change agents and front line service delivery force

for mainstreaming of CWDs and successful implementation of

inclusive education program immensely depends on the capacity and

willingness of teachers to address the diversity of their educational

needs.

Conclusion and recommendations

On the basis of the results of the study, it is concluded that

despite all challenges, mainstream school teachers have a positive

and favorable attitude towards inclusion of CWDs. They are ready

to be part of such interventions provided all prerequisites for

introducing inclusive education are ensured.

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 43

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

It is also concluded that though the teachers are willing

to accept CWDs in their schools, they have a limited capacity to

address special educational needs. Teachers are not provided with

training through regular professional development to address needs

of all learners. Though policies support inclusive education system,

the school infrastructures and facilities are not accessible forCWDs.

Based on the literature review, responses from respondents

and observations by the researchers during school visits, following

are some of the key recommendations:

1. The study recommends that the problem of teachers’ limited

capacity should be addressed at the level of pre-service

teacher training by incorporating inclusive education in the

curriculum. For the teachers who are already in service,

changes should be made in in-service teacher training

curriculum.

2. Departments of educationin universities should take steps to

ensure infrastructural accessibility in all schools. Changes

should also be made at policy level to ensure accessibility in

all future constructions.

3. International Non-Government Organizations, Corporate

Sector and Civil Society Organizations should join hands

with the government for provision of assistive technology

and teaching learning aids for CWDs to ensure their full

participation in learning process in regular classrooms.

4. The government should scale up inclusive education instead

44 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Khan, Hashmi, Khanum

of practicing it in selected schools,so that a maximum

number of CWDs can benefit from such services.

References

Bailey, J., & Du Plessis, D. (1997). Understanding principals’

attitudes towards inclusive schooling. Journal of Educational

Administration, 35(5), 428-438.

Baker, E. T. (1995). The effects of inclusion on learning. Educational

Leadership, 52(4), 33-35

Bunch, G., s& Valeo, A. (2004).Student attitudes toward peers with

disabilities in inclusive and special education schools. Disability

& Society, 19(1), 61-76.

Fakolade, O. A., Adeniyi, S. O., &Tella, A. (2009). Attitude of teachers

towards the inclusion of special needs children in general

education classroom: The case of teachers in some selected

schools in Nigeria. International Electronic Journal of Elementary

education, 1(3), 155-169.

Fernando, S., Yasmin, S., Minto, H., & Khan, N. (2010). Policy and practice

in the educational inclusion of children and young people with

visual impairment in Sri Lanka and Pakistan. The Educator, 22.

Florian, L. (1998). An examination of the practical problems associated

with the implementation of inclusive education policies. Support

forlearning, 13(3), 105-108.

Garner, P. (1996). Students’ views on special educational needs

courses in initial teacher education. British Journal of Special

Education, 23(4), 176-179.

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 45

Inclusive Education in Government Primary Schools

Ghouri, A. M., Abrar, N., & Baloch, A. G. (2010). Attitude of secondary

schools’ principles and teachers toward inclusive education:

Evidence from Karachi, Pakistan. European Journal of Social

Sciences, 15(4), 573-582.

Hsien, M. L. (2007). Teacher attitudes towards preparation for inclusion in

support of a unified teacher preparation program. Post-Script, 8(1).

Retrieved from http://unesco.org.pk/education/teachereducation/

files/National%20Education%20Policy.pdf Khan, I. K., Ahmed,

L., & Ghaznavi, A. (2012). Child friendly inclusive education in

Pakistan. Insight Plus, 5, 18-20.

Lambe, J., & Bones, R. (2006). Student teachers’ attitudes to inclusion:

implications for initial teacher education in Northern Ireland.

International Journal of Inclusive Education, 10(6), 511-527.

LeRoy, B., & Simpson, C. (1996). Improving student outcomes through

inclusive education. Support for Learning, 11(1), 32-36.

Lipsky, D. K., & Gartner, A. (1996). Inclusion, school restructuring,

and the remaking of American society. Harvard Educational

Review, 66(4), 762-797.

McDonnell, A. P., & Hardman, M. L. (1989). The desegregation of

America’s special schools: Strategies for change. Research and

Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 14(1), 68-74.

Ministry of Education (2003-4). The state of education in Pakistan, Policy

and Planning Wing. Pakistan: Government of Pakistan.

National Education Policy of Pakistan (2009). Ministry of Education,

Government of Punjab Retrieved from 0http://unesco.org.pk/

education/teachereducation/files/National%20Education%20

46 Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017)

Khan, Hashmi, Khanum

Policy.pdf

Payne, R., & Murray, C. (1974).Principals’ attitudes toward integration of

the handicapped. Exceptional Children, 41(2), 123-125.

Romi, S., & Leyser, Y. (2006). Exploring inclusion pre service training

needs: A study of variables associated with attitudes and

self‐efficacy beliefs. European Journal of Special Needs

Education, 21(1), 85-105.

Rose, R. (2001). Primary school teacher perceptions of the

conditions required to include pupils with special educational

needs. Educational Review, 53(2), 147-156.

Tahir, R., & Khan, N. (2010). Analytical study of school and teacher

education curricula for students with special educational needs in

Pakistan. Journal of Special Education, 11(6), 85-91.

UNICEF (2003). Examples of inclusive education in Pakistan.The United

Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Regional Office for South

Asia.

UNESCO (2007).Global monitoring report 2008: Education for All by

2015.Will we make it. Paris: United Nations Education, Science

and Cultural Organization.

UNESCO (2009). Towards inclusive education for children with

disabilities: A guideline Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.

org/Library/Documents/disabchild09-en.pdf

United Nation Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (1948). UN

General Assembly.

Vol. 4 No. 1 (June 2017) 47

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) 10 Principle'sDocument5 pagesCurrent Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) 10 Principle'sYousifNo ratings yet

- Ielts Self Study ResourcesDocument9 pagesIelts Self Study ResourcesThai Nguyen Hoang TuanNo ratings yet

- Uptime 201804 PDFDocument49 pagesUptime 201804 PDFCarlos IvanNo ratings yet

- Autistic College Students and COVID-19Document23 pagesAutistic College Students and COVID-19Catarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Interaction With Disabled Person ScaleDocument12 pagesInteraction With Disabled Person ScaleCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- I'm The One With The Child With A DisabilityDocument36 pagesI'm The One With The Child With A DisabilityCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Transition-to-Primary-School-A-literature-review - Dockett & Perry, 2007aDocument37 pagesTransition-to-Primary-School-A-literature-review - Dockett & Perry, 2007aCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- AC AmyDocument10 pagesAC Amy2ilanda7No ratings yet

- Childrensunderstandingof Cancer IJPHRDDocument7 pagesChildrensunderstandingof Cancer IJPHRDCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Talking To Kids About Cancer A Guide For People With Cancer Their Families and FriendsDocument68 pagesTalking To Kids About Cancer A Guide For People With Cancer Their Families and FriendsCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Maltreatment of Children With DisabilitiesDocument13 pagesMaltreatment of Children With DisabilitiesCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- What Makes A Successful Transition To School Views of Australian Parents and TeachersDocument15 pagesWhat Makes A Successful Transition To School Views of Australian Parents and TeachersCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Children S Cancer and Environmental Exposures .1Document7 pagesChildren S Cancer and Environmental Exposures .1Catarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Transforming Practice With HOPE (Healthy Outcomes From Positive Experiences)Document6 pagesTransforming Practice With HOPE (Healthy Outcomes From Positive Experiences)Catarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Beelmann 2021 Stigma Reduction Framework 10892680211056314Document19 pagesBeelmann 2021 Stigma Reduction Framework 10892680211056314Catarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Does Capacity-Building Professional Development EngenderDocument12 pagesDoes Capacity-Building Professional Development EngenderCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Family InterventionDocument21 pagesFamily InterventionCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Co-Development of The CMAP Book - A Tool To ParticipationDocument12 pagesCo-Development of The CMAP Book - A Tool To ParticipationCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Parents Views On Young Children S Distance Learning and Screen Time During COVID 19 Class Suspension in Hong KongDocument18 pagesParents Views On Young Children S Distance Learning and Screen Time During COVID 19 Class Suspension in Hong KongCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Building Capacity For Family Engagement: Lessons LearnedDocument6 pagesBuilding Capacity For Family Engagement: Lessons LearnedCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet in Business Enterprise SimulationDocument4 pagesActivity Sheet in Business Enterprise SimulationAimee LasacaNo ratings yet

- Navedtra 130b Vol-IIDocument148 pagesNavedtra 130b Vol-IIstephenhuNo ratings yet

- Galicto Vs Aquino III FinDocument2 pagesGalicto Vs Aquino III FinTiago VillaloidNo ratings yet

- TP Video Reflection Rubric - ENGDocument3 pagesTP Video Reflection Rubric - ENGZahra EidNo ratings yet

- IPC Part-II PDFDocument38 pagesIPC Part-II PDFHarsh Vardhan Singh HvsNo ratings yet

- List The Elements of A New-Venture Team?Document11 pagesList The Elements of A New-Venture Team?Amethyst OnlineNo ratings yet

- Product Concepts: Prepared by Deborah Baker Texas Christian UniversityDocument47 pagesProduct Concepts: Prepared by Deborah Baker Texas Christian UniversityRajashekhar B BeedimaniNo ratings yet

- Final Pronouncement The Restructured Code - 0Document200 pagesFinal Pronouncement The Restructured Code - 0Juvêncio ChigonaNo ratings yet

- The Syrian Bull WordDocument7 pagesThe Syrian Bull WordScottipusNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Luqman Hakimi Bin Mohd Zamri - October 2018 Set 1 Question PaperDocument15 pagesMuhammad Luqman Hakimi Bin Mohd Zamri - October 2018 Set 1 Question PaperLUQMAN DENGKILNo ratings yet

- Community-Based LearningDocument4 pagesCommunity-Based Learningapi-3862075No ratings yet

- Observation Log and GuidelinesDocument5 pagesObservation Log and Guidelinesapi-540545122No ratings yet

- Iasc Emergency Response Preparedness Guidelines July 2015 Draft For Field TestingDocument56 pagesIasc Emergency Response Preparedness Guidelines July 2015 Draft For Field TestingFatema Tuzzannat BrishtyNo ratings yet

- Use Case DiagramsDocument8 pagesUse Case DiagramsUmmu AhmedNo ratings yet

- Child Find, AssessmentDocument29 pagesChild Find, AssessmentJohnferl DoquiloNo ratings yet

- PEC 3 Module 1 AnswerDocument3 pagesPEC 3 Module 1 AnswerCris Allen Maggay BrownNo ratings yet

- 2017 Olimp Locala VIIDocument3 pages2017 Olimp Locala VIISilviana SuciuNo ratings yet

- Omnibus Motion For Hdo and TpoDocument5 pagesOmnibus Motion For Hdo and TpoMarvie FrandoNo ratings yet

- Class Participation RubricDocument1 pageClass Participation RubricToni Nih ToningNo ratings yet

- ESU Mauritius Newsletter Dec 09Document4 pagesESU Mauritius Newsletter Dec 09esumauritiusNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Eco Adventure ParkDocument16 pagesChapter 1 - Eco Adventure ParkLei RamosNo ratings yet

- Animal Science - Perfect CowDocument4 pagesAnimal Science - Perfect CowDan ManoleNo ratings yet

- Supplier Security Assessment QuestionnaireDocument9 pagesSupplier Security Assessment QuestionnaireAhmed M. SOUISSI100% (1)

- Pe3 Module No. 1 Introduction To DanceDocument5 pagesPe3 Module No. 1 Introduction To DanceGabo AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Business Writing Quick ReferenceDocument3 pagesBusiness Writing Quick ReferencesbahourNo ratings yet

- MGM102 Test 1 SA 2016Document2 pagesMGM102 Test 1 SA 2016Amy WangNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 2nd Quarter EnglishDocument10 pagesGrade 10 2nd Quarter EnglishShin Ren LeeNo ratings yet