Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Patient Have A Hemorrhagic Stroke

Uploaded by

Mario AROriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Patient Have A Hemorrhagic Stroke

Uploaded by

Mario ARCopyright:

Available Formats

THE RATIONAL CLINICIAN’S CORNER

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Does This Patient Have a Hemorrhagic Stroke?

Clinical Findings Distinguishing Hemorrhagic Stroke

From Ischemic Stroke

Shauna Runchey, MD, MPH Context The 2 fundamental subtypes of stroke are hemorrhagic stroke and ische-

Steven McGee, MD mic stroke. Although neuroimaging is required to distinguish these subtypes, the di-

agnostic accuracy of bedside findings has not been systematically reviewed.

CLINICAL SCENARIOS Objective To determine the accuracy of clinical examination in distinguishing hem-

Case 1 orrhagic stroke from ischemic stroke.

A 75-year-old woman with hyperten- Data Sources MEDLINE and EMBASE searches of English-language articles pub-

sion, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes lished from January 1966 to April 2010.

mellitus presents to the emergency Study Selection Prospective studies of adult patients with stroke that compared

department with speech difficulty and initial clinical findings with accepted diagnostic standards of hemorrhagic stroke (com-

right arm weakness. Her symptoms puted tomography or autopsy).

appeared abruptly 6 hours earlier, Data Extraction Both authors independently appraised study quality and ex-

when she awoke in the morning, but tracted relevant data.

several hours passed before she could Data Synthesis Nineteen prospective studies meeting inclusion criteria were iden-

reach her daughter, who then trans- tified (N=6438 patients; n=1528 [24%] with hemorrhage stroke). Several findings

ported her to the hospital. One year significantly increase the probability of hemorrhagic stroke: coma (likelihood ratio [LR],

ago she was diagnosed as having a 6.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.2-12), neck stiffness (LR, 5.0; 95% CI, 1.9-12.8),

transient ischemic attack after present- seizures accompanying the neurologic deficit (LR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.6-14), diastolic blood

ing with a 10-minute episode of right- pressure greater than 110 mm Hg (LR, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.4-14), vomiting (LR, 3.0; 95%

hand incoordination and numbness; CI, 1.7-5.5), and headache (LR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.7-4.8). Other findings decrease the

probability of hemorrhage: cervical bruit (LR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.03-0.47) and prior tran-

subsequent neuroimaging and cardio-

sient ischemic attack (LR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18-0.65). A Siriraj score greater than 1 in-

vascular studies at that time were creases the probability of hemorrhage (LR, 5.7; 95% CI, 4.4-7.4) while a score lower

unrevealing. In the emergency depart- than −1 decreases the probability (LR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.23-0.37). Nonetheless, many

ment, her blood pressure is 140/75 patients with stroke lack any diagnostic finding, and 20% have Siriraj scores between

mm Hg and her pulse is 70/min and 1 and −1, which are diagnostically unhelpful (LR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.77-1.1).

regular. She is alert and oriented but Conclusion In patients with acute stroke, certain findings accurately increase or de-

struggles to generate words or name crease the probability of intracranial hemorrhage, but no finding or combination of

objects. She reports a mild left hemi- findings is definitively diagnostic in all patients, and diagnostic certainty requires neu-

cranial headache. She exhibits right roimaging.

central facial paralysis and right arm JAMA. 2010;303(22):2280-2286 www.jama.com

weakness. Both great toes are down-

going. Do her findings suggest hemor- Author Affiliations: Department of Medicine, Uni-

Case 2 versity of Washington, Seattle.

rhagic or ischemic infarction? How A 62-year-old man presents to the emer- Corresponding Author: Shauna Runchey, MD, MPH,

accurate are these findings? Department of Medicine, University of Washington,

gency department with new-onset left Box 356426, 1959 NE Pacific St, Health Sciences Bldg,

arm and leg weakness. While working Seattle, WA 98195-6426 (srunchey@u.washington

See also Patient Page. .edu).

in his workshop 2 hours earlier, he ex- The Rational Clinical Examination Section Editors:

CME available online at perienced abrupt onset of a severe head- David L. Simel, MD, MHS, Durham Veterans Affairs

www.jamaarchivescme.com ache. Within 10 to 15 minutes, he had Medical Center and Duke University Medical Cen-

and questions on p 2304. ter, Durham, NC; Drummond Rennie, MD, Deputy

difficulty holding tools in his left hand Editor.

2280 JAMA, June 9, 2010—Vol 303, No. 22 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 07/22/2013

DISTINGUISHING HEMORRHAGIC AND ISCHEMIC STROKES

and he required assistance to get to his raphy (CT) of the head, the best test that into the brain, displacing and compress-

car. He has chronic atrial fibrillation and rapidly distinguishes intracerebral hem- ing adjacent tissue, increasing intracra-

has been taking aspirin for the past 4 orrhage from ischemia. nial pressure, and eventually dissect-

years. In the emergency department, his In patients presenting early enough to ing into the ventricles and subarachnoid

blood pressure is 200/108 mm Hg and be considered for thrombolytic therapy, space (FIGURE). Consequently, hemor-

his pulse is 104/min and chaotic. He has the clinical priorities are urgent CT rhage may cause additional symptoms

a dense left hemiparesis, hemianesthe- imaging, stabilization of the patient, iden- beyond neurologic deficits, such as

sia, and a Babinski response. During the tification of stroke mimics (eg, migraine, severe headache (from increased intra-

examination he becomes progres- seizures, hypoglycemia) and contrain- cranial pressure or meningeal irrita-

sively drowsy and vomits twice. Do his dications to thrombolysis, and measure- tion), progressive deterioration after

findings suggest hemorrhagic or ische- ment of the neurologic deficit.5 In such stroke onset (from continued bleed-

mic infarction? How accurate are these patients, a clinician’s impression of hem- ing), vomiting (from increased intra-

findings? orrhage vs ischemia is secondary to these cranial pressure), neck stiffness (from

more pressing matters. Nonetheless, 3 of meningeal irritation), bilateral Babin-

WHY IS THE CLINICAL 4 patients presenting to emergency ski signs (from enlargement of the hem-

EXAMINATION IMPORTANT? departments with stroke are already orrhage beyond the distribution of a

In the United States, new or recurrent beyond the narrow time window for single vessel), and coma (from bilat-

stroke affects about 795 000 individu- thrombolysis,6 and in these patients the eral cerebral dysfunction or uncal her-

als each year and represents the third clinical overall impression may be help- niation).

leading cause of death.1 The 2 funda- ful while awaiting the CT results. The

mental subtypes of stroke are hemor- clinical impression also is essential when METHODS

rhagic stroke (ie, either intracerebral or CT is not immediately available.2,3 Finally, Literature Search Strategy

subarachnoid hemorrhage) and ische- clinical impression is even important in One author (S.R.) searched PubMed

mic stroke (ie, infarction from throm- patients receiving thrombolytics. Accord- (1970 to April 2010), using MEDLINE,

bosis or embolism). In the United ing to treatment guidelines, the infu- and EMBASE (1988 to April 2010), using

States, 87% of these vascular strokes are sion should be immediately discontin- OVID, to identify English-language stud-

ischemic and 13% are hemorrhagic ued (and imaging repeated) if severe ies that evaluated the diagnostic accu-

(10% are intracerebral hemorrhage; 3% headache, acute hypertension, nausea, or racy of clinical history and physical signs

are subarachnoid hemorrhage),1 al- vomiting develop,5 a statement imply- for detecting intracerebral hemorrhage.

though hospital-based surveys from ing that these symptoms and signs sug- The specific search strategy for PubMed

other countries suggest that the per- gest hemorrhage. was (Stroke/diagnosis[Mesh] OR Intra-

centage due to hemorrhage may be as The diagnostic accuracy of clinical cranial Embolism and Thrombosis/

high as 25% to 60%.2,3 Clinicians must findings in distinguishing hemor- diagnosis[Mesh]) AND Intracranial

rapidly distinguish these 2 vascular sub- rhagic and ischemic stroke has not been Hemorrhages/diagnosis[Mesh]) and for

types because they have distinct etiolo- systematically reviewed. In this ar- EMBASE was (exp *Stroke/et, di [Etiol-

gies, prognoses, and treatments. ticle, we summarize the diagnostic ac- ogy, Diagnosis] or exp Brain Hemor-

Herein, we assume that the clinical curacy of all available clinical informa- rhage/et, di [Etiology, Diagnosis] or exp

diagnosis of stroke has already been tion that is easily obtainable to clinicians Brain Infarction/et, di [Etiology, Diag-

made, a subject extensively reviewed in at the bedside—initial patient inter- nosis] and diagnostic accuracy/ or diag-

a prior Rational Clinical Examination view, physical examination, and basic nostic value/). Additional articles were

article.4 Classic descriptions of stroke laboratory tests. In addition, we re- identified from liberal use of the search

suggest that some clinical features may view the diagnostic accuracy of differ- tool “all related articles” in PubMed and

differentiate these subtypes: head- ent stroke scores that combine clini- examination of bibliographies of se-

ache, neck stiffness, vomiting, and coma cal information to predict the risk of lected articles.

are more common in hemorrhagic hemorrhagic infarction.

stroke whereas previous transient is- Study Selection

chemic attacks, atrial fibrillation, and PHYSIOLOGIC ORIGINS Both authors independently read all ar-

atherosclerosis risk factors are more OF SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS ticles relevant to the study question

common in ischemic stroke. Clini- Both cerebral hemorrhage and infarc- and selected those representing unique

cians frequently examine patients with tion cause abrupt dysfunction of neu- patient populations meeting the

these findings in mind to form a clini- rologic tissue, leading to neurologic defi- following inclusion criteria: (1) The

cal impression of whether hemor- cits such as hemiparesis, hemisensory study prospectively enrolled only

rhage or ischemia is more likely. Even loss, aphasia, ophthalmoplegia, and vi- patients presenting to clinicians in a

so, all patients with new strokes must sual field cuts. Cerebral hemorrhage, in hospital or emergency department with

undergo immediate computed tomog- contrast, also causes leakage of blood a diagnosis of stroke, defined as focal

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, June 9, 2010—Vol 303, No. 22 2281

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 07/22/2013

DISTINGUISHING HEMORRHAGIC AND ISCHEMIC STROKES

Figure. Explanation of Additional Symptoms of Intracerebral Hemorrhage

Pathophysiological events Clinical findings

Initial hemorrhage

AXIAL VIEW CORONAL VIEW

Lateral Lateral

ventricle ventricle

Lateral

ventricle

Hemiparesis

Continued bleeding, compression of adjacent tissues, and increased intracranial pressure

AXIAL VIEW CORONAL VIEW S A G I T TA L V I E W

Lateral Lateral

ventricle Lateral ventricle Third ventricle

ventricle

Lateral Headache

ventricle

Tentorium Vomiting

cerebelli Hemiplegia

Third

ventricle Drowsiness

Fourth

Subarachnoid ventricle

space

Brainstem Median

aperture

Dissection of blood into the ventricles and extension of blood into the subarachnoid space; uncal herniation

AXIAL VIEW CORONAL VIEW S A G I T TA L V I E W

Subarachnoid

space

Lateral

ventricle

Neck stiffness

Coma

Subarachnoid

Extension of blood

space

Tentorium Uncal Brainstem via lateral aperture

cerebelli herniation

In the top panel, a small hemorrhage in the right basal ganglia causes left hemiparesis and a clinical presentation indistinguishable from ischemic stroke. As intracerebral

bleeding continues (middle panel), expansion of the hemorrhage exerts a mass effect on the brain, increasing intracranial pressure and causing a midline shift. Clinical

findings characteristic of hemorrhagic stroke manifest, such as progressive neurological deficits, headache, and vomiting. Eventually, blood may dissect into the ven-

tricles and extend into the subarachnoid space via the median and lateral apertures of the fourth ventricle (bottom panel), leading to neck stiffness. In severe hemor-

rhagic stroke, intracerebral expansion of the hemorrhage may result in coma from bilateral cerebral dysfunction or uncal herniation.

2282 JAMA, June 9, 2010—Vol 303, No. 22 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 07/22/2013

DISTINGUISHING HEMORRHAGIC AND ISCHEMIC STROKES

Table 1. Definitions and Diagnostic Accuracy of Stroke Scores Detecting Hemorrhage: Pooled Results a

No. of Hemorrhages, Threshold LR for Hemorrhage

Score Patients No. (%) Definition b Values (95% CI)

Siriraj stroke 3439 1051 (31) (2.5 ⫻ semicoma or 5 ⫻ coma) ⫹ (2 ⫻ vomiting) ⫹ ⬍−1: infarction 0.29 (0.23-0.37)

score13,15-17,26-34 (2 ⫻ headache within 2 h) ⫹ (0.1 ⫻ diastolic −1 to 1: uncertain 0.94 (0.77-1.1)

blood pressure) − (3 ⫻ ⱖ1 of diabetes, angina, ⬎1: hemorrhage 5.7 (4.4-7.4)

intermittent claudication) − 12

Besson 261 46 (18) (2 ⫻ alcohol consumption) ⫹ (1.5 ⫻ plantar response ⬍1: infarction 0.23 (0.01-5)

score10,14 both extensor) ⫹ (3 ⫻ headache) ⫹ (3 ⫻ history ⱖ1: hemorrhage 1.4 (0.92-2.2)

of hypertension) − (5 ⫻ history of transient

ischemic attack) − (2 ⫻ peripheral arterial disease)

− (1.5 ⫻ history of hyperlipidemia) − (2.5 ⫻ atrial

fibrillation on admission)

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LR, likelihood ratio.

a See eTable 2 for results from the individual studies.

b Within each set of parentheses is the number of points awarded if the criterion following the times sign is satisfied. For example, in the Siriraj score, (2.5⫻semicoma or 5⫻coma) means

2.5 points are awarded if the patient has semicoma or 5 points if the patient has coma.

(or at times global) neurologic impair- sitivity, specificity, and positive and hours after presentation, which is

ment of sudden onset and of pre- negative LRs using standard defini- clinically unrealistic.24 The definitions

sumed vascular origin (World Health tions.19 Any differences in data entry of the included stroke scores appear

Organization definition).7 (2) The study were settled by consensus. If any cell in TABLE 1.

used either neuroimaging (CT or mag- in the 2⫻2 table had the value of zero,

netic resonance imaging) or autopsy to 0.5 was added to all cells before calcu- Prevalence of Hemorrhage Stroke

distinguish hemorrhage from ische- lating LRs or pooled estimates. Pooled in Patients Presenting With Stroke

mia (all but 1 study8 exclusively used estimates were calculated using the Der- The prevalence of hemorrhagic stroke

CT). (3) Intracranial hemorrhage re- Simonian and Laird random-effects in these studies was 24% (n = 1528),

ferred only to intracerebral hemor- model.20 Data are presented using LRs with individual study prevalences

rhage (studies enrolling patients with because they function as “diagnostic ranging from 12% to 57% (random-

subarachnoid hemorrhage were ex- weights” that are easily translated to effects summary prevalence, 29%;

cluded). (4) The study presented suf- posttest probability of disease.21 Excel 95% confidence interval [CI], 24%-

ficient information to create 2⫻2 tables 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washing- 35%). In general, the prevalence of

and calculate sensitivity, specificity, and ton) was used for statistical analyses. hemorrhage is lower in studies from

likelihood ratios (LRs). Each study was the United States and Europe (sum-

assigned a quality grade similar to other RESULTS mary prevalence, 15%; 95% CI, 13%-

articles in the Rational Clinical Exami- Study Characteristics 18%) than in those from Asia and

nation series9 according to whether We retrieved 109 citations for full- Africa (summary prevalence, 34%;

sample sizes were adequate, cases were text review, 19 of which met our in- 95% CI, 27%-41%). Some of this dif-

consecutive, and comparison with the clusion criteria and presented data from ference probably reflects real differ-

diagnostic standard was independent 6438 patients worldwide with stroke ences around the world but it also

(in assigning quality grades, we con- (eFigure and eTable 1). The methods may indicate referral bias (ie, in coun-

sidered studies with ⱖ100 total pa- and enrollment of these studies varied tries with more limited access to CT

tients and ⱖ30 patients with hemor- widely. The maximal allowed interval and thrombolytic therapy, patients

rhage to be large; see eTable 1 [available between onset of neurologic symp- thought to have hemorrhage may be

at http://www.jama.com]). In all stud- toms and CT scanning was less than 3 more likely referred for CT). A small

ies, patients were enrolled at the time days in 68% of studies, less than 15 days number of patients (range, 2.0%-

of presentation and clinical data were in 16%, and 15 days or more or un- 2.9%) experienced a stroke mimic that

collected before the criterion standard known in 16%. was neither hemorrhagic nor ischemic

for the subtype of stroke (hemorrhage We identified 6 stroke scores that (eg, attributable to tumor, subdural

vs ischemia). No patient received combined clinical findings to calcu- hematoma, or tuberculosis).13,26,27,35

thrombolytic medications. Several in- late probability of hemorrhagic

vestigators8,10-18 supplied additional un- stroke.10,17,22-25 Three were excluded Individual Findings

published information from their origi- because they lacked extensive exter- Several findings significantly increase

nal studies. nal validation beyond the original the probability of hemorrhagic stroke

cohort.22,23,25 A fourth score, the once (LR 95% CI does not cross 1.0). In or-

Statistical Analyses popular Allen (Guy’s Hospital) score, der of their LRs (the higher the value

Both authors independently extracted was excluded because it required of the LR, the greater the increase in

data from each study to calculate sen- clinical information first available 24 probability of hemorrhagic stroke),

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, June 9, 2010—Vol 303, No. 22 2283

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 07/22/2013

DISTINGUISHING HEMORRHAGIC AND ISCHEMIC STROKES

these findings include coma (LR, 6.2; 2.6; 95% CI, 1.6-4.2) (TABLE 2 and of consciousness, and xanthochromia

95% CI, 3.2-12), neck stiffness (LR, 5.0; eTable 3 ). The finding of xanthochro- were each investigated in only a single

95% CI, 1.9-12.8), seizures accompa- mia during lumbar puncture also study.

nying neurologic deficit (LR, 4.7; 95% greatly increases the probability of hem- Several findings significantly de-

CI, 1.6-14), diastolic blood pressure orrhage (LR, 15; 95% CI, 7.7-29), al- crease the probability of hemorrhagic

greater than 110 mm Hg (LR, 4.3; 95% though this test is no longer routinely stroke, thus increasing the probability

CI, 1.4-14), vomiting (LR, 3.0; 95% CI, performed to identify intracranial hem- of ischemic stroke. These findings in-

1.7-5.5), headache (LR, 2.9; 95% CI, orrhage. The findings of diastolic blood clude the presence of a cervical bruit

1.7-4.8), and loss of consciousness (LR, pressure greater than 110 mm Hg, loss (LR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.03-0.47), ab-

Table 2. Accuracy of Findings for Diagnosing Hemorrhagic Stroke a

No. of Hemorrhage, Sensitivity, % Specificity, % Positive LR Negative LR

Finding Patients No. (%) (95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI)

Risk factors

Age ⱕ60 y35 1510 237 (16) 50 (43-56) 70 (68-73) 1.7 (1.4-1.9) 0.71 (0.63-0.82)

Alcohol consumption10 178 27 (15) 48 (29-67) 70 (62-77) 1.6 (1-2.5) 0.75 (0.51-1.1)

Male16-18,28,35 3107 635 (20) 57 (53-61) 51 (47-54) 1.2 (1.1-1.3) 0.85 (0.77-0.94)

Hypertension10,11,16-18,28,35 4193 776 (19) 68 (60-75) 40 (33-47) 1.1 (1.0-1.2) 0.88 (0.77-1.01)

Cigarette smoking11,28 1187 216 (18) 38 (22-55) 52 (45-79) 0.79 (0.45-1.4) 1.2 (0.79-1.8)

Diabetes mellitus11,13,16,28,29,35 3866 681 (18) 17 (9-25) 74 (66-81) 0.64 (0.43-0.95) 1.1 (1.0-1.2)

Prior stroke17,35 1622 295 (18) 11 (4-18) 79 (67-91) 0.59 (0.17-2.0) 1.1 (0.88-1.4)

Hyperlipidemia10,11,16 2028 300 (15) 7 (0-15) 78 (68-89) 0.48 (0.2-1.1) 1.1 (1.1-1.1)

Coronary artery disease11,16,35 3420 523 (15) 6 (0-13) 83 (67-100) 0.44 (0.31-0.61) 1.1 (1.0-1.3)

Atrial fibrillation11,16,35 3420 523 (15) 4 (0-7) 90 (89-91) 0.44 (0.25-0.78) 1.1 (1.05-1.1)

Peripheral artery disease10,35 1710 270 (16) 3 (1-5) 91 (86-96) 0.41 (0.2-0.83) 1.1 (1.0-1.1)

Prior transient ischemic 3478 523 (15) 7 (3-11) 79 (75-84) 0.34 (0.18-0.65) 1.2 (1.1-1.3)

attack10,11,16,35

Symptoms

Seizures accompanying neurologic 2497 385 (15) 9 (6-12) 98 (97-100) 4.7 (1.6-14) 0.93 (0.9-0.96)

deficit11,18,35

Vomiting13,16-18,29,35 2947 577 (20) 34 (17-52) 93 (90-96) 3.0 (1.7-5.5) 0.73 (0.59-0.91)

Headache10,11,13,16-18,29,35 3974 708 (18) 46 (41-52) 82 (75-89) 2.9 (1.7-4.8) 0.66 (0.56-0.77)

Loss of consciousness17 174 75 (43) 47 (35-58) 82 (74-89) 2.6 (1.6-4.2) 0.65 (0.52-0.82)

Acute onset of deficit11 887 109 (12) 44 (35-53) 32 (29-35) 0.65 (0.52-0.81) 1.7 (1.4-2.1)

Physical signs

Kernig sign, Brudzinski sign, 50 23 (46) 15 (0-29) 98 (93-100) 8.2 (0.44-150) 0.87 (0.73-1.0)

or both29

Level of consciousness: 1161 223 (19) 35 (19-50) 94 (89-99) 6.2 (3.2-12)

coma11,17,18

Neck stiffness17,29 223 97 (43) 20 (12-28) 97 (93-100) 5.0 (1.9-12.8) 0.83 (0.75-0.92)

Diastolic blood pressure 50 23 (46) 48 (27-68) 89 (77-100) 4.3 (1.4-14) 0.59 (0.39-0.89)

⬎110 mm Hg29

Level of consciousness: 1161 223 (19) 32 (20-44) 82 (69-96) 2.0 (1.0-3.9)

drowsy11,17,18

Plantar response: both extensor10,17 370 106 (29) 16 (9-23) 92 (89-96) 1.8 (0.99-3.4)

Plantar response: 370 106 (29) 62 (44-81) 39 (27-51) 1 (0.87-1.2)

single extensor10,17

Hemiparesis11,16,35 3420 523 (15) 63 (25-100) 33 (0-66) 0.96 (0.9-1.0) 1.1 (1.0-1.2)

Plantar response: both flexor10,17 370 106 (29) 11 (5-17) 74 (69-80) 0.45 (0.25-0.81)

Level of consciousness: alert17,18 274 114 (42) 23 (15-30) 31 (12-51) 0.35 (0.24-0.5)

Cervical bruit35 1510 237 (16) 1 (0-2) 93 (91-94) 0.12 (0.03-0.47) 1.1 (1.0-1.1)

Laboratory

Xanthochromia in cerebrospinal 231 41 (18) 71 (57-85) 95 (92-98) 15 (7.7-29) 0.31 (0.19-0.49)

fluid8

Atrial fibrillation on 1087 142 (13) 2 (0-4) 82 (64-100) 0.19 (0.06-0.59) 1.2 (1.0-1.5)

electrocardiogram10,11

Clinician’s overall impression

Hemorrhage most likely diagnosis28 300 111 (37) 76 (68-84) 88 (83-92) 6.2 (4.2-9.3) 0.28 (0.20-0.39)

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LR, likelihood ratio.

a See eTable 3 for results from the individual studies.

2284 JAMA, June 9, 2010—Vol 303, No. 22 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 07/22/2013

DISTINGUISHING HEMORRHAGIC AND ISCHEMIC STROKES

sence of xanthochromia on lumbar lence of hemorrhage in a particular rhagic infarction from 13% to 4%. Her

puncture (LR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.19- study and that study’s hemorrhage LR CT scan reveals an infarction in the left

0.49), history of transient ischemic (P = .38 by Pearson correlation) or ra- posterior frontal lobe.

attack (LR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18-0.65), tio of hemorrhage LR to infarction LR,

peripheral artery disease (LR, 0.41; 95% an indicator of overall discriminatory Case 2

CI, 0.2-0.83), and history of atrial fi- power (P=.47). The patient’s findings of headache, se-

brillation (LR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.25- Another concern might be the defi- vere hypertension, emesis, drowsi-

0.78). The finding of cervical bruit was nition of stroke used by most investi- ness, and rapid neurologic progres-

investigated in only 1 study. gators, a post hoc definition by the sion all strongly suggest hemorrhagic

World Health Organization requiring stroke, and the calculated Siriraj score

Combinations of Findings that neurologic deficits persist for longer is 5.3, which is test-positive for hem-

The diagnostic accuracies of the Bes- than 24 hours. This raises the possibil- orrhage (scores ⬎1: LR, 5.7), a result

son score (2 studies) and the Siriraj ity that our conclusions may not ap- that increases the probability of hem-

score (13 studies) are shown in Table 1. ply to patients presenting to emer- orrhage from 13% to 46%. In this pa-

The Siriraj score is most accurate, in- gency departments with only 1 to 2 tient, urgent CT scanning reveals an in-

creasing the probability of hemor- hours of symptoms. Nonetheless, we tracerebral hemorrhage centered in the

rhage when it indicates hemorrhage believe that the patients in these stud- right basal ganglia, with surrounding

(LR, 5.7; 95% CI, 4.4-7.4) and decreas- ies are similar to those with shorter du- edema and shift of the midline struc-

ing it when it indicates ischemic in- ration of symptoms for the following tures to the left.

farction (LR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.23- reasons. First, the 24-hour time limit

0.37). Nonetheless, in all patients was based on an outdated and arbi- CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

presenting with stroke, 20% were clas- trary distinction between transient is- Other than previous transient ische-

sified as uncertain by the Siriraj score chemic attack and stroke that no longer mic attack, classic risk factors for ce-

(LR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.77-1.1), a diag- is applicable and probably was mis- rebral atherosclerosis—such as diabe-

nostically unhelpful result because it leading because most patients with tran- tes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, cigarette

changes probability of hemorrhage little sient ischemic attack have less than 30 smoking, and hypertension—fail to dis-

or not at all (LRs near the value of 1.0 minutes of symptoms and their symp- tinguish the 2 subtypes of stroke, either

do not change probability). toms are unwitnessed by physicians.36 because the risk factor is only weakly

Second, few patients with only 1 to 2 linked to ischemic stroke (eg, in the

Overall Clinical Impression hours of symptoms experience com- Framingham Stroke Profile,38 a tool for

In a single study, clinician overall im- plete resolution by 24 hours (unless assessing risk of stroke, diabetes or ciga-

pression of hemorrhage (LR, 6.2; 95% they receive treatment). In the pla- rette smoking increases the risk of

CI, 4.2-9.3) or ischemia (LR, 0.28; 95% cebo group of the National Institute of stroke only half as much as atrial fibril-

CI, 0.20-0.39), without using explicit Neurological Disorders and Stroke trial lation) or because the risk factor is

rules or allowing classification into an of recombinant human tissue plasmino- linked to both hemorrhage and ische-

“uncertain” category, was as accurate gen activator, only 2% of patients pre- mia, thus nullifying its diagnostic value

as the Siriraj score. This suggests that senting with less than 3 hours of neu- (eg, hypertension is linked to both ce-

these experienced clinicians are using rologic deficits had resolution of rebral atherosclerosis—and, thus, is-

findings not addressed in our study, findings at 24 hours.37 chemia—and intracerebral hemor-

combining them in nonlinear ways, or rhage).

deriving greater accuracy from more SCENARIO RESOLUTION We conclude that in patients with

thorough familiarity with the actual pa- Case 1 stroke, additional clinical findings char-

tients seen in these studies. The patient’s findings suggest ische- acteristic of hemorrhage—headache,

mic stroke. Her pretest probability of vomiting, severe hypertension, neck

Limitations hemorrhagic stroke is 13% (in the stiffness, and coma—increase the prob-

One potential limitation is the meth- United States), and the findings of pre- ability of hemorrhagic stroke. Even so,

odological diversity of these studies, vious transient ischemic attack, alert many patients with hemorrhage lack

making it unwise to pool results, but mental status, and absence of severe hy- any distinctive findings or are unclas-

when we reexamined the Siriraj score pertension or Babinski sign decrease the sifiable by stroke scores. Neither the

in various subgroups—patients receiv- probability of hemorrhagic stroke even clinical impression of experienced cli-

ing CT within 72 hours, studies meet- further. Even with the presence of head- nicians nor the most accurate stroke

ing grade 1 criteria, or studies meet- ache, her calculated Siriraj score is −5.5, score can improve the posttest prob-

ing grade 2 or 3 criteria—the LRs were which is test-positive for ischemic in- ability of hemorrhage to greater than

largely unchanged (eTable 4). Also, we farction (scores ⬍−1: LR, 0.29), de- 50%. While combinations of findings

found no correlation between preva- creasing her probability of hemor- are more predictive than individual

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, June 9, 2010—Vol 303, No. 22 2285

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 07/22/2013

DISTINGUISHING HEMORRHAGIC AND ISCHEMIC STROKES

findings, diagnostic certainty requires 6. Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, Schneider A, et al; Neu- 23. Panzer RJ, Feibel JH, Barker WH, Griner PF. Pre-

roscience Institute. Eligibility for recombinant tissue dicting the likelihood of hemorrhage in patients

neuroimaging. plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke: a with stroke. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(10):1800-

population-based study. Stroke. 2004;35(2):e27- 1803.

Author Contributions: Drs Runchey and McGee had

e29. 24. Allen CM. Clinical diagnosis of the acute stroke

full access to all of the data in the study and take re-

7. WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. The syndrome. Q J Med. 1983;52(208):515-523.

sponsibility for the integrity of the data and the ac-

World Health Organization MONICA Project (Moni- 25. Efstathiou SP, Tsioulos DI, Zacharos ID, et al. A

curacy of the data analysis.

toring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular new classification tool for clinical differentiation be-

Study concept and design: Runchey, McGee.

Disease): a major international collaboration. J Clin tween haemorrhagic and ischaemic stroke. J Intern

Acquisition of data: Runchey, McGee.

Epidemiol. 1988;41(2):105-114. Med. 2002;252(2):121-129.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Runchey, McGee.

8. Britton M, Hultman E, Murray V, Sjoholm H. The 26. Badam P, Solao V, Pai M, Kalantri SP. Poor ac-

Drafting of the manuscript: Runchey, McGee.

diagnostic accuracy of CSF analyses in stroke. Acta Med curacy of the Siriraj and Guy’s Hospital stroke scores

Critical revision of the manuscript for important in-

Scand. 1983;214(1):3-13. in distinguishing haemorrhagic from ischaemic stroke

tellectual content: Runchey, McGee.

9. Simel DL, Rennie D, Bossuyt PM. The STARD state- in a rural, tertiary care hospital. Natl Med J India. 2003;

Statistical analysis: Runchey, McGee.

ment for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: ap- 16(1):8-12.

Study supervision: McGee.

plication to the history and physical examination. J Gen 27. Hui AC, Wu B, Tang AS, Kay R. Lack of clinical

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Intern Med. 2008;23(6):768-774. utility of the Siriraj stroke score. Intern Med J. 2002;

Online-Only Material: The eFigure and eTables 1

10. Besson G, Robert C, Hommel M, Perret J. Is it clini- 32(7):311-314.

through 4 are available online at http://www.jama

cally possible to distinguish nonhemorrhagic infarct 28. Ozeren A, Bicakci S, Burgut R, Sarica Y, Bozdemir

.com.

from hemorrhagic stroke? Stroke. 1995;26(7): H. Accuracy of bedside diagnosis vs Allen and Siriraj

Additional Contributions: We appreciate the exper-

1205-1209. stroke scores in Turkish patients. Eur J Neurol. 2006;

tise and assistance of Sherry Dodson, University of Wash-

11. Bogousslavsky J, Van Melle G, Regli F. The Lau- 13(6):611-615.

ington, who helped conduct the literature search. Michael

sanne Stroke Registry: analysis of 1000 consecutive 29. Nyandaiti YW, Bwala SA. Validation study of the

Fitch, MD, PhD, Wake Forest University School of Medi-

patients with first stroke. Stroke. 1988;19(9):1083- Siriraj stroke score in north-east Nigeria. Niger J Clin

cine, and Amanda Green, MD, Paris Regional Medical

1092. Pract. 2008;11(3):176-180.

Center, provided helpful advice on earlier versions of

12. Hui AC, Man CY, Tang AS, Au-Yeung KM. Com- 30. Wadhwani J, Hussain R, Raman PG. Nature

the manuscript. No compensation was received.

puted tomography evaluation in acute stroke: retro- of lesion in cerebrovascular stroke patients: clinical

spective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2002;8(3):177- stroke score and computed tomography scan brain

REFERENCES 180. correlation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:

13. Kolapo KO, Ogun SA, Danesi MA, Osalusi BS, 777-781.

1. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al; Ameri- Odusote KA. Validation study of the Siriraj stroke score 31. Kochar DK, Joshi A, Agarwal N, Aseri S, Sharma

can Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke in African Nigerians and evaluation of the discrimi- BV, Agarwal TD. Poor diagnostic accuracy and appli-

Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke sta- nant values of its parameters: a preliminary prospec- cability of Siriraj stroke score, Allen score and their com-

tistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart tive CT scan study. Stroke. 2006;37(8):1997-2000. bination in differentiating acute haemorrhagic and

Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statis- 14. Mader TJ, Mandel A. A new clinical scoring sys- thrombotic stroke. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;

tics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):480- tem fails to differentiate hemorrhagic from ischemic 48(6):584-588.

486. stroke when used in the acute care setting. J Emerg 32. Kan CH, Lee SK, Low CS, Velusamy SS, Cheong

2. Brainin M, Teuschl Y, Kalra L. Acute treatment and Med. 1998;16(1):9-13. I. A validation study of the Siriraj stroke score. Int J

long-term management of stroke in developing 15. Ng PW, Sha KY. Clinical stroke scores in Chinese Clin Pract. 2000;54(10):645-646.

countries. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(6):553-561. population. Stroke. 1996;27(4):773-774. 33. Ilić T, Jovicić A, Lepić T, Magdić B, Cirković S. Ce-

3. Durai Pandian J, Padma V, Vijaya P, Sylaja PN, 16. Nouira S, Boukef R, Bouida W, et al. Accuracy of rebral infarction vs intracranial hemorrhage—validity

Murthy JM. Stroke and thrombolysis in developing two scores in the diagnosis of stroke subtype in a mul- of clinical diagnosis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 1997;54

countries. Int J Stroke. 2007;2(1):17-26. ticenter cohort study. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53 (4):299-309.

4. Goldstein LB, Simel DL. Is this patient having a (3):373-378. 34. Daga MK, Sarin K, Negi VS. Comparison of Siri-

stroke? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2391-2402. 17. Poungvarin N, Viriyavejakul A, Komontri C. Siri- raj and Guy’s Hospital score to differentiate supra-

5. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al; Ameri- raj stroke score and validation study to distinguish su- tentorial ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes in the

can Heart Association; American Stroke Association pratentorial intracerebral haemorrhage from infarction. Indian population. J Assoc Physicians India. 1994;

Stroke Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Cardio- BMJ. 1991;302(6792):1565-1567. 42(4):302-303.

vascular Radiology and Intervention Council; Athero- 18. Shah FU, Salih M, Saeed MA, Tariq M. Validity 35. Massaro AR, Sacco RL, Scaff M, Mohr JP. Clini-

sclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of of Siriraj stroke scoring. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. cal discriminators between acute brain hemorrhage and

Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Work- 2003;13(7):391-393. infarction: a practical score for early patient

ing Groups. Guidelines for the early management of 19. Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Tugwell P. Clinical Epi- identification. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;60(2-A):

adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the Ameri- demiology: A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine. 185-191.

can Heart Association/American Stroke Association Boston, MA: Little Brown; 2006. 36. Fisher CM. Transient ischemic attacks. N Engl J

Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardio- 20. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical Med. 2002;347(21):1642-1643.

vascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. 37. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and

Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Qual- 21. McGee S. Simplifying likelihood ratios. J Gen In- Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasmino-

ity of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary tern Med. 2002;17(8):646-649. gen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med.

Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurol- 22. Woisetschläger C, Kittler H, Oschatz E, et al. Out- 1995;333(24):1581-1587.

ogy affirms the value of this guideline as an educa- of-hospital diagnosis of cerebral infarction versus in- 38. Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB.

tional tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38(5): tracranial hemorrhage. Intensive Care Med. 2000; Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framing-

1655-1711. 26(10):1561-1565. ham Study. Stroke. 1991;22(3):312-318.

2286 JAMA, June 9, 2010—Vol 303, No. 22 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Fordham University User on 07/22/2013

You might also like

- Excess Deaths Involving CVD in England An Anlysis and ExplainerDocument36 pagesExcess Deaths Involving CVD in England An Anlysis and ExplainerJamie White100% (2)

- Diagnosis and Management of Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument25 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Subarachnoid HemorrhageMisael ClintonNo ratings yet

- OBGYN Revalida Review 2019Document74 pagesOBGYN Revalida Review 2019anonymous100% (1)

- A Guide To Clinical Differential Diagnosis of Oral Mucosal LesionDocument46 pagesA Guide To Clinical Differential Diagnosis of Oral Mucosal LesionFasmiya ShariffNo ratings yet

- Seizure After StrokeDocument6 pagesSeizure After StrokenellieauthorNo ratings yet

- Malpresentation and Malposition Omer Ahmed MirghaniDocument78 pagesMalpresentation and Malposition Omer Ahmed Mirghaniاروى فتح الرحمن100% (1)

- @MBS MedicalBooksStore 2019 The PDFDocument394 pages@MBS MedicalBooksStore 2019 The PDFDsdentalNo ratings yet

- Cryptogenic Stroke: Clinical PracticeDocument10 pagesCryptogenic Stroke: Clinical PracticenellieauthorNo ratings yet

- Cryptogenic Stroke 2016Document10 pagesCryptogenic Stroke 2016tatukyNo ratings yet

- HSA Controversias 2016Document9 pagesHSA Controversias 2016Ellys Macías PeraltaNo ratings yet

- AJO CRAO-stroke Editorial ACADocument2 pagesAJO CRAO-stroke Editorial ACAJunru YanNo ratings yet

- Definition of Stroke SLIDESDocument122 pagesDefinition of Stroke SLIDESdev burmanNo ratings yet

- Stroke Mimics and Chameleons: J. Stephen Huff, MDDocument13 pagesStroke Mimics and Chameleons: J. Stephen Huff, MDfooNo ratings yet

- Missed Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis in The Emergency Department by Emergency Medicine and Neurology ServicesDocument7 pagesMissed Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis in The Emergency Department by Emergency Medicine and Neurology ServicesReyhansyah RachmadhyanNo ratings yet

- Management of Stroke in The Neurocritical Care UnitDocument25 pagesManagement of Stroke in The Neurocritical Care UnitBush HsiehNo ratings yet

- FKTR FixDocument3 pagesFKTR FixvinaNo ratings yet

- (19330693 - Journal of Neurosurgery) Decompressive Hemicraniectomy - Predictors of Functional Outcome in Patients With Ischemic StrokeDocument7 pages(19330693 - Journal of Neurosurgery) Decompressive Hemicraniectomy - Predictors of Functional Outcome in Patients With Ischemic StrokeRandy Reina RiveroNo ratings yet

- Acute Ischemic StrokeDocument9 pagesAcute Ischemic Strokepuskesmas tarikNo ratings yet

- Int J Stroke 2014 Benavente 1057 64Document8 pagesInt J Stroke 2014 Benavente 1057 64Fauzan IndraNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Presenting With Second-Degree Type I Sinoatrial Exit Block: A Case ReportDocument15 pagesHHS Public Access: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Presenting With Second-Degree Type I Sinoatrial Exit Block: A Case Reportcitra annisa fitriNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Cerebral Stroke Case Report, Complications and Associated FactorsDocument5 pagesIschemic Cerebral Stroke Case Report, Complications and Associated Factorsfaradilla wiyandaNo ratings yet

- Main 51 ???Document5 pagesMain 51 ???pokharelriwaj82No ratings yet

- Ischemic StrokeDocument13 pagesIschemic StrokearthurbaidoodouglasNo ratings yet

- A 25-Year-Old Man With New-Onset Seizures PDFDocument8 pagesA 25-Year-Old Man With New-Onset Seizures PDFMr. LNo ratings yet

- In-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackDocument15 pagesIn-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackferrevNo ratings yet

- Subclinical Hypertensive Heart Disease in Black Patients With Elevated Blood Pressure in An Inner-City Emergency DepartmentDocument9 pagesSubclinical Hypertensive Heart Disease in Black Patients With Elevated Blood Pressure in An Inner-City Emergency DepartmentDianNo ratings yet

- Stroke NarrativeDocument10 pagesStroke Narrativecfalcon.medicinaNo ratings yet

- Levy2012 PDFDocument9 pagesLevy2012 PDFDianNo ratings yet

- Stroke PreventionDocument8 pagesStroke PreventionjaanhoneyNo ratings yet

- Does ThrombolysisDocument7 pagesDoes ThrombolysisNovendi RizkaNo ratings yet

- WASID Trial 2005Document12 pagesWASID Trial 2005cristhian_carvaja_13No ratings yet

- Acv PDFDocument14 pagesAcv PDFFelipe AlcainoNo ratings yet

- Uso Milrinone VasoespasmoDocument7 pagesUso Milrinone VasoespasmoHernando CastrillónNo ratings yet

- Cardiogenic Shock: Current Concepts and Improving Outcomes: Harmony R. Reynolds and Judith S. HochmanDocument13 pagesCardiogenic Shock: Current Concepts and Improving Outcomes: Harmony R. Reynolds and Judith S. HochmanRohith MGNo ratings yet

- Clinical Relevance of Acute Cerebral Microinfarcts in Vascular Cognitive ImpairmentDocument10 pagesClinical Relevance of Acute Cerebral Microinfarcts in Vascular Cognitive Impairmentzefri suhendarNo ratings yet

- Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.6Document19 pagesAneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.6Aldy Setiawan PutraNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Jan Claassen, Soojin ParkDocument17 pagesSeminar: Jan Claassen, Soojin ParkRaul DoctoNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Venous ThrombosisDocument14 pagesCerebral Venous ThrombosisSrinivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Hemato Si StrokeDocument6 pagesHemato Si Strokeseaside16girlNo ratings yet

- Medico-legal Aspects of Surgically Treating Ruptured Cerebral Arteriovenous MalformationsDocument9 pagesMedico-legal Aspects of Surgically Treating Ruptured Cerebral Arteriovenous MalformationsVoicu AndreiNo ratings yet

- 0122 StemiDocument29 pages0122 Stemienfermeras uciNo ratings yet

- Thick and Diffuse Cisternal Clot Independently Predicts Vasospasm-Related Morbidity and Poor Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument9 pagesThick and Diffuse Cisternal Clot Independently Predicts Vasospasm-Related Morbidity and Poor Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid HemorrhageVanessa LandaNo ratings yet

- Siriraj 2Document4 pagesSiriraj 2Winda MelatiNo ratings yet

- Overview of Hemorrhagic Stroke Care in The Emergency Unit: Natalie Kreitzer and Daniel WooDocument11 pagesOverview of Hemorrhagic Stroke Care in The Emergency Unit: Natalie Kreitzer and Daniel WooIstiqomahsejatiNo ratings yet

- 1 s20 S0002934322006295 Main - 221027 - 063744Document10 pages1 s20 S0002934322006295 Main - 221027 - 063744Vaomir DiazNo ratings yet

- Vidence Ased IagnosticsDocument41 pagesVidence Ased IagnosticsAnisa ArmadaniNo ratings yet

- Noc110069 346 351Document6 pagesNoc110069 346 351Carlos AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Iht Nejm 2014Document10 pagesIht Nejm 2014Ademir Ruiz EcheverríaNo ratings yet

- Can Transient BP High Risk Cerebral InfarctsDocument9 pagesCan Transient BP High Risk Cerebral InfarctsshofidhiaaaNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Cerebral Stroke Case Report, Complications and Associated FactorsDocument7 pagesIschemic Cerebral Stroke Case Report, Complications and Associated FactorsAlfa DexterNo ratings yet

- Cardio Cerebral InfarctionDocument2 pagesCardio Cerebral InfarctionNicodemus TriatmojoNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Jstrokecerebrovasdis 2017 05 011Document8 pages10 1016@j Jstrokecerebrovasdis 2017 05 011nellieauthorNo ratings yet

- Journal StrokeDocument5 pagesJournal StrokeRika Sartyca IlhamNo ratings yet

- Vasospasm Milrinone PayenDocument7 pagesVasospasm Milrinone PayenmlannesNo ratings yet

- Manual Aspiration Thrombectomy in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Clinical ExperienceDocument9 pagesManual Aspiration Thrombectomy in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Clinical ExperienceArdiana FirdausNo ratings yet

- Higher Troponin Levels Linked to Embolic StrokesDocument7 pagesHigher Troponin Levels Linked to Embolic StrokesafbmgNo ratings yet

- Evidencia en Craniectomia DescompresivaDocument22 pagesEvidencia en Craniectomia DescompresivaJosé Luis ChavesNo ratings yet

- Acute Ischemic Stroke ReviewDocument10 pagesAcute Ischemic Stroke ReviewAkim DanielNo ratings yet

- Head Position in Acute Stroke Trial Statistical Analysis PlanDocument5 pagesHead Position in Acute Stroke Trial Statistical Analysis PlanNurul AzmiyahNo ratings yet

- Jamieson 2009Document7 pagesJamieson 2009JovitaNo ratings yet

- En Do Card It IsDocument30 pagesEn Do Card It IsPamela LusungNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial Infarction and Heart FailureDocument5 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarction and Heart FailureWirawan PrabowoNo ratings yet

- Cohorte Retrospectivda NOAF in CRITICSLLY ILLDocument8 pagesCohorte Retrospectivda NOAF in CRITICSLLY ILLARTURO YOSHIMAR LUQUE MAMANINo ratings yet

- Case-Based Device Therapy for Heart FailureFrom EverandCase-Based Device Therapy for Heart FailureUlrika Birgersdotter-GreenNo ratings yet

- Acute Stroke Management in the Era of ThrombectomyFrom EverandAcute Stroke Management in the Era of ThrombectomyEdgar A. SamaniegoNo ratings yet

- Approach To Child With Fever: Liew Qian YiDocument33 pagesApproach To Child With Fever: Liew Qian YinavenNo ratings yet

- Crim 5Document12 pagesCrim 5Mel DonNo ratings yet

- Instructors Manual 6th EditionDocument120 pagesInstructors Manual 6th EditionSean BokelmannNo ratings yet

- REVISI (Adelita Setiawan 2)Document7 pagesREVISI (Adelita Setiawan 2)Adelita SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy ForDocument7 pagesCognitive Behavioral Therapy Forsyarifah husnaNo ratings yet

- A Case Report On Hyponatremia Leading Sign of Hypopituitarism (Secondary To Adrenal Insufficiency)Document4 pagesA Case Report On Hyponatremia Leading Sign of Hypopituitarism (Secondary To Adrenal Insufficiency)International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- IDSA - Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis in WomenDocument7 pagesIDSA - Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis in Womenamalia puspita dewiNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Palliative Care: Ns. Dwi Yunita Haryanti, S.Kep., M.KesDocument17 pagesPain Management in Palliative Care: Ns. Dwi Yunita Haryanti, S.Kep., M.Kesiqbal yudo5No ratings yet

- ACEs FlyerDocument2 pagesACEs Flyermahima sajanNo ratings yet

- Antenatal AssessmentDocument24 pagesAntenatal AssessmentIshrat PatelNo ratings yet

- Air in Space Flyer Prezentare ProduseDocument9 pagesAir in Space Flyer Prezentare ProduseValentin MalihinNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Health Sciences and Research: Fetal Umbilical Cord Circumference Measurement and Birth WeightDocument6 pagesInternational Journal of Health Sciences and Research: Fetal Umbilical Cord Circumference Measurement and Birth WeightFatma ElzaytNo ratings yet

- Medical Student Syndrome Bjmp-2019-12-1-A003: British Journal of Medical Practitioners January 2019Document6 pagesMedical Student Syndrome Bjmp-2019-12-1-A003: British Journal of Medical Practitioners January 2019Nabila AjmaliaNo ratings yet

- Chanca Piedra - Various Properties (Potential) PDFDocument17 pagesChanca Piedra - Various Properties (Potential) PDFSurya WijayaNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Project RoughDocument16 pagesChemistry Project RoughDinakaran JaganNo ratings yet

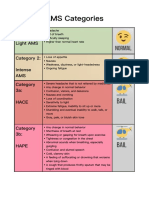

- AMS Symptoms and CategoriesDocument1 pageAMS Symptoms and CategoriesyyggvcNo ratings yet

- Psychi BulletDocument4 pagesPsychi BulletHEALTH TIPSNo ratings yet

- Final Oxygen Therapy and Monitoring Devices FM CommentedDocument56 pagesFinal Oxygen Therapy and Monitoring Devices FM CommentedDesalegnNo ratings yet

- 2022醫療急救 無線電醫療作業Document2 pages2022醫療急救 無線電醫療作業Yu-ting FengNo ratings yet

- Fall Health & Wellness (October 2022)Document20 pagesFall Health & Wellness (October 2022)Watertown Daily TimesNo ratings yet

- Review of Studies On Flight Attendant Health and Comfort in Airliner CabinsDocument9 pagesReview of Studies On Flight Attendant Health and Comfort in Airliner CabinsStudentNo ratings yet

- Ms - CardiovascularDocument70 pagesMs - CardiovascularMark OngNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology 2Document235 pagesOphthalmology 2yididiyagirma30No ratings yet

- A008 MicroVue C4d EnglishDocument15 pagesA008 MicroVue C4d EnglishAlisNo ratings yet

- Zubiaga, R-Jeane S. - BSN 3 - For PlagscanDocument41 pagesZubiaga, R-Jeane S. - BSN 3 - For PlagscanR-Jeane ZubiagaNo ratings yet