Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beyond Evidence The Moral Case For International M

Uploaded by

Chinaza AjuonumaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beyond Evidence The Moral Case For International M

Uploaded by

Chinaza AjuonumaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/6908268

Beyond Evidence: The Moral Case for International Mental Health

Article in American Journal of Psychiatry · September 2006

DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.8.1312 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

96 199

3 authors:

Vipin Patel Benedetto Saraceno

Indian Institute of Science Universidade NOVA de Lisboa

105 PUBLICATIONS 16,933 CITATIONS 167 PUBLICATIONS 7,446 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Arthur Kleinman

Harvard University

103 PUBLICATIONS 14,428 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Patient-Physician Trust in China View project

Biostatistics View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Benedetto Saraceno on 18 April 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Editorial

Beyond Evidence: The Moral Case

for International Mental Health

T he global burden of disease attributable to mental, neurological, and substance use

disorders is expected to rise from 12.3% in 2000 to 14.7% in 2020 (1). This rise will be

particularly sharp in developing countries. Research has documented the socioeco-

nomic determinants of many disorders, the profound impact on the lives of those af-

fected and their families, and the lack of appropriate care in developing countries. The

enormous gap between mental health needs and the services in developing countries

has been documented in international reports, culminating in the World Health Report

2001 (2). This evidence has increased the profile of international mental health, but ac-

tion still remains limited. With every new public health challenge, mental health is once

more relegated to the background. We argue that moral arguments are just as important

as evidence to make the case for mental health in-

tervention. At the center of these moral arguments

“The overwhelming is the need to reclaim the place of mental health at

majority of the 400 the heart of international public health. We consider

million persons with some moral arguments for international mental

health and an example from another area of public

mental disorders health in which the moral case was an important

globally are not being enough argument for making policy changes and

implementing interventions.

provided with…basic

No health without mental health. Mental health

mental health care.” is closely linked with virtually all global public health

priorities. Alcohol abuse is a major risk factor for un-

safe sexual behavior, and persons with human im-

munodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) have high

rates of cognitive impairment and depression (3). Stress and anxiety predispose to myo-

cardial infarction, and the latter leads to higher rates of depression (4). Maternal depres-

sion is associated with childhood failure to thrive in developing countries; failure to thrive

can lead to developmental delays and psychiatric problems in later life (5). Alcohol abuse

and personality disorder frequently precede violence and depression, and suicide fre-

quently follows (6). The moral case is that there is no health without mental health. Men-

tal health interventions must be tied to any program dealing with physical health.

Mental disorders are treatable in developing countries. Clinical trials have dem-

onstrated the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of locally feasible treatments for depres-

sion, schizophrenia, and substance abuse in developing countries (7–9). All these studies

share one finding: mental illnesses can be treated with cheap and technically simple

treatments. The work of committed grassroots organizations demonstrates how this sec-

tor has been implementing mental health interventions at low cost (10). The moral case

is that it is unethical to deny effective, acceptable, and affordable treatment to millions

of persons suffering from treatable disorders. Community and primary care treatment

programs must be generously supported by donor agencies.

Paying for new psychiatric drugs. Many developing countries were able to produce

generic versions of drugs because of a less rigid enforcement of international patent

regulation. Since a substantial proportion of drug costs are met out of pocket, this al-

lowed newer medications to be accessible to low-income groups. This situation was

changed with the enforcement of the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights inter-

national agreement in 2005. The agreement dictates that any drug patented after 2005

1312 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 163:8, August 2006

EDITORIAL

will not be available except at the price set by the company that holds the patent (11).

Governments can exempt diseases that are life-threatening or national emergencies

from the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights charter. Mental illness does not fig-

ure as an exemption category. The moral case is that the mentally ill have a right to ac-

cess affordable, evidence-based treatments. Mental illnesses must be excluded from the

Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights charter.

Reversing the brain drain. The most startling finding of the World Health Organi-

zation Atlas report is the impossibly enormous inequity in the distribution of mental

health manpower in the world (12). A tiny fraction of this manpower resides in regions

of the world where over 90% of the global population lives. Despite this glaring ineq-

uity, the demand for specialists in richer countries only grows, worsening the brain-

drain of mental health resources from developing countries. The vast majority of these

professionals have been trained in publically funded medical schools. The moral case

is that the people of poor countries should not be paying for the mental health care of

those living in the richer world. There needs to be an acknowledgment that institutions

in developed countries have an ethical obligation to facilitate the return of profession-

als and to foster long-term partnerships with developing countries to build mental

health capacity.

Violating human rights. There is a history of human rights violations of persons with

mental disorders across the world, but today the most disturbing examples are found in

developing countries. The Asia edition of the newsmagazine Time from Nov. 24, 2003,

detailed contemporary accounts of the lives of people living in mental hospitals in

Southeast Asia. Patients, typically long-term residents, lose contact with their families,

rarely see a mental health professional, are treated with old drugs with severe side ef-

fects, are offered few rehabilitative therapies, are kept in crowded wards with no hint of

dignity, and are given unmodified electroconvulsive therapy. The Erwadi tragedy in In-

dia in 2001, where over 20 persons with mental illness were burned to death when a fire

swept the healing temple where they were chained to their beds, reminds us of human

rights abuses that take place under the guise of traditional medicine. The stigma of

mental illness is so great that the mentally ill are unable to gain employment, finish

schooling, marry, live independently, or have their care paid for by insurance compa-

nies. The moral case is that the rights of the mentally ill continue to be denied by many

sectors in society. We need to provide technical and financial support for hospitals to re-

form, to enable the development of community care programs, to raise mental health

literacy in the community and among health workers, and to ensure that basic rights are

monitored and enforced.

Social change and mental health. Most developing countries are witnessing social

and economic changes at a pace that is unparalleled in history. Not everyone has bene-

fited from these changes. Economic change is coupled with migration from rural to ur-

ban areas, disrupting social networks and household economies. The decrease of trade

barriers reducing costs of consumer items is coupled with cheap imports, leading to un-

employment of small-scale entrepreneurs and farmers. The reduction in state budgets

is being most acutely felt in social spending, where they are most needed. The rising

tide of suicides and premature mortality in some countries, as vividly seen in the alco-

hol-related deaths of men in Eastern Europe and the suicides of farmers in India, indig-

enous peoples in South America, and young women in rural areas in China, can be at

least in part linked to rapid economic and social change (13, 14). The moral case is that

mental health problems are not a luxury item on the health agenda of the poor and mar-

ginalized. Mental disorders must be included in programs directed to promoting the

health of the poor and mental health indicators used to evaluate the larger social im-

pact of globalization.

The overwhelming majority of the 400 million persons with mental disorders globally

are not being provided with even the basic mental health care that we know they should

Am J Psychiatry 163:8, August 2006 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 1313

EDITORIAL

and can receive. Research evidence will not reduce this inequity. To make a change, the

moral case must be heard.

Consider the moral argument that persons with HIV/AIDS in developing countries

had the right to access antiretroviral drugs, that the state had to provide them for free,

that drug companies had to reduce their prices, that apparently complex treatment reg-

imens could be provided by primary health care providers with appropriate training

and support, that discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS had to be combated

vigorously, and that knowledge about HIV/AIDS was the most powerful tool to combat

stigma. These arguments were moral and human rights based. The arguments were

made by a coalition of academics, community leaders, people living with HIV/AIDS,

rock stars, and public heroes. The case they made was so compelling that governments

from India to South Africa changed their policy on antiretroviral drugs. Drug companies

agreed to reduce prices of medicines. The World Health Organization decided on 3×5 as

their lead initiative, aiming to get antiretroviral drugs to 3 million people by 2005.

We believe that the time is ripe for such a global mental health advocacy initiative that

makes the moral case for the mentally ill. It is unacceptable to continue business as

usual. Borrowing from the lessons of our colleagues in other areas of public health, such

an initiative could take the form of a Global Alliance for Mental Health, under the um-

brella of the World Health Organization, in which mental health professionals work

alongside patients, families, and public health groups. The practical design of policies,

programs, and interventions is most likely to be effective when articulated with a moral

orientation toward sufferers of mental illnesses. The Alliance’s primary goal would be to

spearhead a movement to increase access to evidence-based care, perhaps a 5×10 pro-

gram to get 5 million untreated patients into treatment and rehabilitation programs by

2010. Equally important goals would be to combat stigma through concerted cam-

paigns directed at various sectors of society and to strengthen the capacity of health

systems to care for the mentally ill. A key task would be to mobilize the massive re-

sources needed to support mental health program development in poor countries.

Mental health professionals in rich countries have an important role to play. They can

be advocates to their own health systems to ensure that the moral case is heard and ap-

propriate actions supported. As individuals, they can commit their time to activities

that tackle some of the issues on the international mental health agenda. We believe

that our ultimate professional goal as mental health professionals in a globalized world

is to secure a reasonable opportunity for people with mental disorders to achieve better

health outcomes. We already have the evidence we need to make the case for interna-

tional mental health; it is the moral argument that we now need to make.

References

1. Murray CJL, Lopez AD: Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: global burden

of disease study. Lancet 1997; 349:1498–1504

2. World Health Organization: The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope.

Geneva, WHO, 2001

3. Catalan J (ed): Mental Health and HIV Infection. Psychological and Psychiatric Aspects. London, Taylor &

Francis, 1999

4. Penninx BWJH, Beekman AT, Honig A, Deeg DJH, Schoevers RA, van Eijk JTM, van Tilburg W: Depression and

cardiac mortality: results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:227

5. Patel V, Rahman A, Jacob KS, Hughes M: Effect of maternal mental health on infant growth in low income

countries: new evidence from South Asia. BMJ 2004; 328:820–823

6. World Health Organization: World Report on Violence and Health: Summary. Geneva, WHO, 2002

7. Chatterjee S, Patel V, Chatterjee A, Weiss H: Evaluation of a community based rehabilitation model for

chronic schizophrenia in a rural region of India. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182:57–62

8. Patel V, Araya R, Bolton P: Treating depression in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health 2004; 9:539–

541

9. Wu Z, Detels R, Zhang J, Li V, Li J: Community-based trial to prevent drug use amongst youth in Yunnan,

China. Am J Public Health 2002; 92:1952–1957

10. Patel V, Thara R: Meeting Mental Health Needs in Developing Countries: NGO Innovations in India. New

Delhi, Sage Publications, 2003

1314 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 163:8, August 2006

EDITORIAL

11. Patel V, Andrade C: Pharmacological treatment of severe psychiatric disorders in the developing world: les-

sons from India. CNS Drugs 2003; 17:1071–1080

12. World Health Organization: Atlas Country Profiles of Mental Health Resources. Geneva, WHO, 2001

13. Sundar M: Suicide in farmers in India. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:585–586

14. Phillips MR, Liu H, Zhang Y: Suicide and social change in China. Cult Med Psychiatry 1999; 23:25–50

VIKRAM PATEL, PH.D.

BENEDETTO SARACENO, M.D.

ARTHUR KLEINMAN, M.D.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Patel, Sangath Centre, Alto-Porvorim, Goa India 403521;

vikram.patel@lshtm.ac.uk (e-mail).

Drs. Patel, Saraceno, and Kleinman report no conflict of interest.

Clinical Views You Can Use

Have you seen our new feature? This year the Journal debuted “Treat-

ment in Psychiatry,” a regular feature that begins with a hypothetical case

illustrating a problem in current clinical practice. The authors review cur-

rent data on prevalence, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. The

article concludes with the authors’ treatment recommendations for cases

like the one presented.

Since January, the Journal has provided expert opinions on the follow-

ing cases:

January: Borderline Personality Disorder and Suicidality

February: New-Onset Bipolar Disorder in Late Life: A Case of

Mistaken Identity

March: The Schizophrenia Prodrome

April: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Military Returnees

From Afghanistan and Iraq

May: Hallucinations in Children and Adolescents:

Considerations in the Emergency Setting

June: The Importance of Routine for Preventing Recurrence

in Bipolar Disorder

July: Psychotic and Manic-like Symptoms During Stimulant

Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

This month’s Treatment in Psychiatry is on Antidepressants and Bipo-

lar Disorder and can be found on p. 1337

Am J Psychiatry 163:8, August 2006 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 1315

View publication stats

You might also like

- Mental Health Class NotesDocument3 pagesMental Health Class Notessuz100% (4)

- Position PaperDocument14 pagesPosition Paperantonette gammaru100% (1)

- Academic Self-HandicappingDocument1 pageAcademic Self-HandicappingAlexis Autor SuacilloNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Priorities For Global Mental Health Research in LMICDocument24 pagesChallenges and Priorities For Global Mental Health Research in LMICKelvin TungNo ratings yet

- hsc.12749 - Are Mental Health Tribunals Operating in Accordance With International Human Rights StandardsDocument20 pageshsc.12749 - Are Mental Health Tribunals Operating in Accordance With International Human Rights StandardsAdrian WhyattNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Key to Sustainable DevelopmentDocument32 pagesMental Health Key to Sustainable Developmentfionakumaricampbell6631No ratings yet

- Empowering People For Mental Health - A Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesEmpowering People For Mental Health - A Literature ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- WISH Mental Health ReportDocument52 pagesWISH Mental Health ReportMatías ArgüelloNo ratings yet

- AlzheimersDementia 2021Document13 pagesAlzheimersDementia 2021TheawakenedmindsNo ratings yet

- Global Mental HealthDocument4 pagesGlobal Mental HealthFIRDA NURSANTINo ratings yet

- Social Determinants of Mental Health Full ReportDocument55 pagesSocial Determinants of Mental Health Full ReportneetiprakashNo ratings yet

- Mental Health StudyDocument4 pagesMental Health StudyKrishna SapkotaNo ratings yet

- Eugenics as a Factor in the Prevention of Mental DiseaseFrom EverandEugenics as a Factor in the Prevention of Mental DiseaseNo ratings yet

- Disparities in Knowledge, Attitude and Practices On Mental Health Among Healthcare Workers and Community Members in Meru County, KenyaDocument22 pagesDisparities in Knowledge, Attitude and Practices On Mental Health Among Healthcare Workers and Community Members in Meru County, KenyaMuhammad IdrisNo ratings yet

- PIIS0140673607612434Document1 pagePIIS0140673607612434api-26621755No ratings yet

- 3 Editorial BDocument2 pages3 Editorial BmirleinnomineNo ratings yet

- Surgeon General Mental Health Report - 1999 - DCF PDFDocument494 pagesSurgeon General Mental Health Report - 1999 - DCF PDFatjoeross100% (2)

- World Mental Health Day - 2022Document17 pagesWorld Mental Health Day - 2022TesitaNo ratings yet

- 0010 Pre FinalDocument246 pages0010 Pre FinalDanielle Kiara ZarzosoNo ratings yet

- Social Determinants Mental HealthDocument54 pagesSocial Determinants Mental HealthSánchez JenniferNo ratings yet

- Lay CounselorDocument12 pagesLay Counselornurul cahya widyaningrumNo ratings yet

- Mental Health IndustryDocument11 pagesMental Health Industryjordan gallowayNo ratings yet

- CENA C2.editedDocument21 pagesCENA C2.editedEllen Gonzalvo-CabutihanNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Crisis in PakistanDocument2 pagesMental Health Crisis in PakistanUmair Pervaiz GillNo ratings yet

- Scaling-Up Mental Health ServicesDocument12 pagesScaling-Up Mental Health ServicesPierre LaPaditeNo ratings yet

- Read Et Al 2009 PDFDocument16 pagesRead Et Al 2009 PDFJana ChihaiNo ratings yet

- Mental illness overview and plansDocument15 pagesMental illness overview and plansbeibhydNo ratings yet

- 1992 Impotence 091 PDFDocument37 pages1992 Impotence 091 PDFm faisalNo ratings yet

- Future of MHDocument2 pagesFuture of MHAmitranjan BasuNo ratings yet

- Psychedelic Science Contemplative Practices and Indigenous and Other Traditional Knowledge Systems Towards Integrative Community-Based Approaches IDocument17 pagesPsychedelic Science Contemplative Practices and Indigenous and Other Traditional Knowledge Systems Towards Integrative Community-Based Approaches IMariana CNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Mental DisordersDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Mental Disordersfvhdgaqt100% (1)

- Mental Health Report Vol I 10 06 2016 PDFDocument190 pagesMental Health Report Vol I 10 06 2016 PDFVaishnavi JayakumarNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Care in India: Old Aspirations Renewed HopeDocument973 pagesMental Health Care in India: Old Aspirations Renewed HopeVaishnavi JayakumarNo ratings yet

- Saraceno B Freeman M Funk M. PUBLIC MENTAL HEALTHDocument20 pagesSaraceno B Freeman M Funk M. PUBLIC MENTAL HEALTHenviosmentalmedNo ratings yet

- Ywfbask PDFDocument3 pagesYwfbask PDFqwert ytrewqNo ratings yet

- Zamora CHN ResearchDocument9 pagesZamora CHN ResearchHazelGatuslaoZamoraNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Mental HealthDocument41 pagesResearch Paper On Mental HealthExample100% (1)

- Eating Disorders The Big IssueDocument3 pagesEating Disorders The Big IssueReztariestyadiNo ratings yet

- Globalising Mental Health: A Neoliberal ProjectDocument7 pagesGlobalising Mental Health: A Neoliberal ProjectlizardocdNo ratings yet

- Intelligence and Personality As PredictorsDocument96 pagesIntelligence and Personality As PredictorsTrifan DamianNo ratings yet

- Human rights in mental healthcare A review of current global situationDocument14 pagesHuman rights in mental healthcare A review of current global situationVanshika OberoiNo ratings yet

- Psychiatrization of Society A Conceptual FrameworkDocument11 pagesPsychiatrization of Society A Conceptual Frameworkcoletivo peripatetikosNo ratings yet

- First Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaDocument14 pagesFirst Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaAbirajanNo ratings yet

- Family Mental Health NursingDocument21 pagesFamily Mental Health Nursinghyunra kimNo ratings yet

- Mental Health HealthDocument6 pagesMental Health Healthsarahjehad12345No ratings yet

- Is Borderline Personality Disorder A Serious Mental Illness?Document7 pagesIs Borderline Personality Disorder A Serious Mental Illness?Carolina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Mental Heath AFRDocument16 pagesMental Heath AFRthursday8893No ratings yet

- Documen 2 TDocument11 pagesDocumen 2 TRhodius NogueraNo ratings yet

- Farmer-Scope For Global HealthDocument2 pagesFarmer-Scope For Global HealthMauricio López-RuizNo ratings yet

- LEXICON International Media Guide For Mental Health - FINAL - LexiconDocument16 pagesLEXICON International Media Guide For Mental Health - FINAL - LexiconVaishnavi JayakumarNo ratings yet

- Mhn-Issues, Trends, Magnitude, Contemporary Practice HealthDocument15 pagesMhn-Issues, Trends, Magnitude, Contemporary Practice HealthAna MikaNo ratings yet

- Challenges of managing mental health in the UAEDocument6 pagesChallenges of managing mental health in the UAEReem AlkaabiNo ratings yet

- Developing Counseling Skills For HealthcareDocument165 pagesDeveloping Counseling Skills For HealthcareHemn HawleryNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Mental Health in IndiaDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Mental Health in Indiaqzetcsuhf100% (1)

- Vacarolis Chapter OutlinesDocument181 pagesVacarolis Chapter Outlinesamashriqi100% (1)

- Mental Health and Sensing: October 2020Document17 pagesMental Health and Sensing: October 2020Ahmed AliNo ratings yet

- Pilot StudyDocument6 pagesPilot StudyStanley Yakic BasaweNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay Final DraftDocument11 pagesArgumentative Essay Final Draftapi-624112595No ratings yet

- Guideline MinimunDocument14 pagesGuideline MinimunsofinoyaNo ratings yet

- Bab IDocument20 pagesBab IbadrulNo ratings yet

- Mental Health in IndiaDocument6 pagesMental Health in IndiaStarlin MythriNo ratings yet

- RD TIPS - 10 Choose Ans From A ListDocument2 pagesRD TIPS - 10 Choose Ans From A ListJess NguyenNo ratings yet

- 1 01 Foodborne IllnessDocument28 pages1 01 Foodborne Illnessapi-329321140No ratings yet

- National Guideline On Integrated Vector Management 2020 NewDocument140 pagesNational Guideline On Integrated Vector Management 2020 NewNeha AmatyaNo ratings yet

- SOFA Score: What It Is and How To Use It in TriageDocument4 pagesSOFA Score: What It Is and How To Use It in TriageDr. rohith JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Overview of Public Health NursingDocument6 pagesOverview of Public Health NursingMariah Jane TaladuaNo ratings yet

- Personality Psychology Domains of Knowledge About Human Nature 5th Edition Larsen Solutions ManualDocument17 pagesPersonality Psychology Domains of Knowledge About Human Nature 5th Edition Larsen Solutions Manualcivilianpopulacy37ybzi100% (28)

- Feed Addditives NEW ANN 211Document44 pagesFeed Addditives NEW ANN 211Mohit BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Lit Ing 060523Document6 pagesLit Ing 060523gloriussihombing18No ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 2Document13 pages10 - Chapter 2Rukhsana HabibNo ratings yet

- Saadat Hasan Manto, Partition, and Mental Illness Through The Lens of Toba Tek SinghDocument6 pagesSaadat Hasan Manto, Partition, and Mental Illness Through The Lens of Toba Tek SinghIrfan BalochNo ratings yet

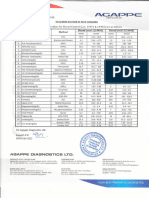

- Agappe Diagnostics Control ValuesDocument1 pageAgappe Diagnostics Control ValuesDinil KannurNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan for Risk of Bleeding During PregnancyDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan for Risk of Bleeding During PregnancybananakyuNo ratings yet

- Include Invest: InnovateDocument28 pagesInclude Invest: InnovateAstrisa FaadhilahNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Discovering Psychology 7th Edition Ebook PDF PDF ScribdDocument41 pagesInstant Download Discovering Psychology 7th Edition Ebook PDF PDF Scribdjeana.gomez838100% (39)

- Diagnosis and Management of Dyslipidemia in Family PracticeDocument41 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Dyslipidemia in Family PracticeKai ChuaNo ratings yet

- Group 3-Kaposi SarcomaDocument25 pagesGroup 3-Kaposi SarcomaShiangNo ratings yet

- Occupational English Test: Writing Sub-Test: Nursing Time Allowed: Reading Time: 5 Minutes Writing Time: 40 MinutesDocument2 pagesOccupational English Test: Writing Sub-Test: Nursing Time Allowed: Reading Time: 5 Minutes Writing Time: 40 MinutesMathea Cohen0% (1)

- Krok Review: How To Prepare Krok TestDocument84 pagesKrok Review: How To Prepare Krok Testgaurav100% (2)

- Kent's RepertoryDocument89 pagesKent's RepertoryDrx Rustom AliNo ratings yet

- INFECTION Control and PREVENTION-1Document49 pagesINFECTION Control and PREVENTION-1Jerry AbleNo ratings yet

- Milpersman 1910-402Document1 pageMilpersman 1910-402benpickensNo ratings yet

- FSRH Ukmec Summary September 2019Document11 pagesFSRH Ukmec Summary September 2019Kiran JayaprakashNo ratings yet

- PharmacokineticsDocument95 pagesPharmacokineticsSonalee ShahNo ratings yet

- 111 Predatory UGC's Revised White List Has 111 More Predatory Journals - Science ChronicleDocument31 pages111 Predatory UGC's Revised White List Has 111 More Predatory Journals - Science ChronicleP meruguNo ratings yet

- Pahade Et Al 2021 Indian (Marathi) Version of The Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (Spadi) TranslatioDocument8 pagesPahade Et Al 2021 Indian (Marathi) Version of The Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (Spadi) TranslatioAnnisa Assyifa YustianNo ratings yet

- Vital Signs - Measurements of Basic Body FunctionsDocument27 pagesVital Signs - Measurements of Basic Body FunctionsJames Paulo AbandoNo ratings yet

- Coida Service Book Version 23Document53 pagesCoida Service Book Version 23Lesedi ModibaneNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Nutrition and Rheumatoid Arthritis in The Omics' EraDocument23 pagesNutrients: Nutrition and Rheumatoid Arthritis in The Omics' EraMikhael FeliksNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B OverviewDocument11 pagesHepatitis B OverviewJose RonquilloNo ratings yet