Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Starn (1991) - Missing The Revolution-Anthropologists and The War in Peru

Starn (1991) - Missing The Revolution-Anthropologists and The War in Peru

Uploaded by

gaby0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views30 pagesOriginal Title

Starn (1991) - Missing the Revolution-Anthropologists and the War in Peru

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views30 pagesStarn (1991) - Missing The Revolution-Anthropologists and The War in Peru

Starn (1991) - Missing The Revolution-Anthropologists and The War in Peru

Uploaded by

gabyCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 30

Missing the Revolution: Anthropologists and the War in Peru

Orin Star

Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 6, No. 1. (Feb., 1991), pp. 63-91.

Stable URL

hitp:/flinks.jstor-org/sicisici=0886-7356% 28199 102% 296%3 1% 3C63%3AMTRAAT%3E2,0.CO%3B2-N

Cultural Anthropology is currently published by American Anthropological Association.

Your use of the ISTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

hup:/www,jstororglabout/terms.hml. ISTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you

have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and

you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

hutp:/wwwjstor.org/jounals/anthro. html

ch copy of any part of'a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the sereen or

printed page of such transmission,

ISTOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of

scholarly journals. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact support @ jstor.org.

hupulwww jstor.org/

Tue Oct 3 15:30:40 2006

Missing the Revolution:

Anthropologists and the War in Peru

Orin Starn

Stanford University

On 17 May 1980, Shining Path guerillas burned ballot boxes in the Andean

village of Chuschi and proclaimed their intention to overthrow the Peruvian state

Playing on the Inkarri myth of Andean resurrection from the cataclysm of con-

quest, the revolutionaries had chosen the 199th anniversary of the execution by

the Spanish colonizers ofthe neo-Inca rebel Tupac Amaru. Chuschi, though, pre-

figured not rebirth but a decade of death. It opened a savage war between the

‘guerrillas and government that would claim more than 15,000 lives during the

1980s."

For hundreds of anthropologists in the thriving regional subspecialty of An-

dean studies, the rise of the Shining Path came as a complete surprise. Dozens of

ethnographers worked in Peru’s southern highlands during the 1970s. One of the

best-known Andeanists, R. T. Zuidema, was directing a research project in the

Rio Pampas region that became a center of the rebellion. Yet no anthropologist

realized a major insurgency was about to detonate, a revolt so powerful that by

1990 Peru’s civilian government had ceded more than half the country to military

‘command,

‘The inability of ethnographers to anticipate the insurgency raises important

«questions. For much of the 20th century, after all, anthropologists had figured as

principal experts on life in the Andes. They positioned themselves as the “good”

‘outsiders who truly understood the interests and aspirations of Andean people; and

they spoke with scientific authority guaranteed by the firsthand experience of

fieldwork. Why, then, did anthropologists miss the gathering storm of the Shining

ath” What does this say about ethnographic understandings of the highlands?

How do events in Peru force us to rethink anthropology on the Andes?

From the start, I want to emphasize that it would be unfair to fault anthro-

pologists for not predicting the rebellion. Ethnographers certainly should not be

in the business of forecasting revolutions. In many respects, moreover, the Shin-

ing Path’s success would have been especially hard to foresee. A pro-Cultural

Revolution Maoist splinter from Peru's regular Communist Party, the group

formed in the university in the provincial highland city of Ayacucho. It was led

by a big-jowled philosophy professor named Abimac! Guzman with thick glasses

and a rare blood disease called policitimea.* Guzmién viewed Peru as dominated

by a bureaucratic capitalism that could be toppled only through armed struggle.

6

64 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

{A first action of his guerrillas in Lima was to register contempt for “bourgeois

revisionism” by hanging a dead dog in front of the Chinese embassy. Most ob-

servers intially dismissed the Shining Path, Sendero Luminoso, as a bizarre but

lunthreatening sect. This was fiercely doctrinaire Marxism in the decade of per-

estroika

‘What I will claim, though, is that most anthropologists were remarkably un-

attuned to the conditions which made possible the rise of Sendero. First, they

tended to ignore the intensifying interlinkage of Peru's countryside and cities,

villages and shantytowns, Andean highlands and lowlands of the jungle and coast

‘These interpenetrations created the enormous pool of radical young people of

amalgamated rural/urban identity who would provide an effective revolutionary

force. Second, anthropologists largely overlooked the climate of sharp unrest

across the impoverished countryside. Hundreds of protests and land invasions tes-

tified to a deep-rooted discontent that the guerrillas would successfully exploit.

To begin accounting for the gaps in ethnographic knowledge about the high-

lands, the first half of this essay introduces the concept of Andeanism.* Here 1

refer to representation that portrays contemporary highland peasants as outside

the flow of modern history. Imagery of Andean life as little changed since the

‘Spanish conquest has stretched across discursive boundaries during the 20th cen-

tury to become a central motif in the writings of novelists, politicians, and trav-

clers as well asthe visual depictions of filmmakers, painters, and photographers.

{believe Andcanism also operated in anthropology, and helps to explain why so

‘many ethnographers did not recognize the rapidly tightening interconnections that

were a vital factor in the growth of the Shining Path

GEER thowgh. was not the only influence on anthropologists of the

1960 and 1970s, The growing importance S160) 3 baIG AEB in

international anthropology theory of the period also conditioned ethnographic

views of the Andes. In the second half of the essay, I argue thatthe strong impact

of these two theoretical currents produced an intense preoccupation with issues of

adaptation, ritual, and cosmology. This limited focus, in turn, assists in account-

ing for why most anthropologists passed over the profound rural dissatisfaction

with the status quo that was to become a second enabling factor in Sendero's rapid

My mapping of Andeanist anthropology starts with Billie Jean Isbell’s To

Defend Ourselves: Ecology and Ritual in an Andean Village (1977). Through

close reading of this synthetic and widely read ethnography, I begin to outline the

imprint of Andeanism on anthropological thinking and to explore how the heavy

deployment of ecological and symbolic approaches led to the oversight of political

ferment in the countryside. Isbell’s book has a special significance because its

‘Andean village was Chuschi, the hamlet where the Shining Path’s revolt would

explode just five years after Isbell’s departure

1 juxtapose To Defend Ourselves with a remarkable but little-known book

called Ayacucho: Hunger and Hope (1969) by an Andean-born agronomist and

future Shining Path leader named Antonio Diaz Martinez.* Hunger and Hope

proves it was possible to formulate a very different view of the highlands from

MISSING THE REVOLUTION. 65

that of most Andeanist anthropology. While Isbell and other ethnographers de-

picted discrete villages with fixed traditions, Diaz saw syncretism and shifting

identities. Most anthropologists found a conservative peasantry. Diaz, by con-

trast, perceived small farmers as on the brink of revolt. Passages of Hunger and

Hope foreshadow the Shining Path's subsequent dogmatic brutality. Yet the man

‘who would become the reputed “number three" in the Maoist insurgency, after

Abimael Guzman and Osmén Morote, discovered an Ayacucho that escaped the

‘voluminous anthropology literature, a countryside about to burst into conflict.

Through criticism of Andeanist anthropology, my account points to alter-

natives. 1 press for recognition of what historian Steve Stern (1987.9) calls “the

‘manifold ways whereby peasants have continuously engaged in their political

worlds”; and I argue for an understanding of modern Andean identities as dy-

‘namie, syneretic, and sometimes ambiguous. Finally, 1 seek to develop an anal-

ysis that does not underplay the Shining Path’s violence yet recognizes the in

‘mate ties of many of the guerrillas to the Andean countryside and the existence of

rural sympathies forthe revolt.

| feel a certain unease about writing on the Andes and the Shining Path

nderology"”—the study of the guerrillas—is a thriving enterprise. In my

View, a sense of the intense human suffering caused by the war to0 often disap-

pears in this work, The terror becomes simply another field for scholarly debate

‘This essay is open to criticism for contributing to the academic commodification

‘of Peru's pain, But I offer the account in a spirit of commitment, No outside it

tervention—and certainly not by anthropologists—is at present likely to change

the deadly logic of the war. | hope, though, that sharper anthropological views of

the situation will help others to understand the violence and to join the struggle

for life

Isbell wrote To Defend Ourselves from fieldwork in 1967, 1969-70, and

1974-75. Closely observed and richly detailed, the book presents the village of

‘Chuschi as divided into two almost caste-like segments: Quechua-speaking peas-

ants and Spanish-speaking teachers and bureaucrats. An intermediate category

appears more peripherally, migrants from Chuschi to Lima. Like other Andean:

ists, Isbell positions herself firmly with the Quechua-speaking comuneros. The

‘mestizos, even the dirt-poor teachers, figure as the bad guys, domineering and

Without Isbell's knowledge or appreciation of Andean traditions.

Isbell’s analysis revolves around the proposition that Chuschi's peasants had

‘ured inward to maintain their traditions against outside pressures. The comu-

neros, she argued, had built a symbolic and social order whose binary logic

Isbell (1977:11) made her mission to document “the structural

defenses the indigenous population has constructed against the increasing domi-

nation of the outside world,

(66. CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Iselregsred that Chuschi was a eglonal market centr with a church,

stool and Health pos. She noted tha tucks pled the dit highway between

Cust and the iy of Ayacucho. We ea ofthe constant in people and

foods between Chuschl and not only Ayacicho ut alo Lin andthe coc gow:

ing eglons of the upper Amazon, More than a quan of Chusch's population

had moved wo Lima, Many others migrated seasonally. Even he pean

inigrane maintained closets in thet naive village, rtuning prod and

ieepng ails dnd.

When it came to representing Chuschino cule, however, Ibell dow

played mine and change. Instead he concentrated cn how terial kine

ios, reciprocity, ctumology, and ecological management of Chuschi's

Diaz (1969:34) summed up his dislike of development and belief in the rev-

olutionary potential of Ayacuchan peasants in a passionate passage with strong

Andeanist overtones:

ere the man of the Andes lived under a centralized economy, until the white predator

‘who lasted for 300 years and his successor the modern mestiz0: governor, priest, con

aressman, public employee, propagandists and sellers of technology, who say they

will achieve "“development.”' “Development” of whom?. if they don't even stop 0

lear about the native culture, or even the economie structure, how will they be able

{0 develop i? But nevertheless, this autochthonous people stands on its feet, with

hope forthe future, wit faith in its efforts, and one day will break the chains that

impede its development.

Diaz’s language reiterates that Andeanism does not always accompany a vision

‘of peasants as conservative. It did for anthropologists with their disinterest in pol-

ities. But Diaz, like the indigenista socialists of the 1920s and 1930s, connected

his belief in the survival of “autochthonous” traditions with an assurance about

the possibility of change. Lo andino became a seed of purity that would flower in

anew social order,

Despite the heteroglot identity ofits own cadre, the Shining Path would also

invoke the concept of a return to uncorrupted Andean origins. In the "popular

war” against the “reactionaries and their imperialist masters,” certified an article

in the semiofficial party newspaper I Diario, “the Andean people advance

the Quechua, aymara, and chanka advances." Where Sendero differs from other

socialist alternatives is the frightening rigidity of its vanguardism. The absolutism

of the Senderistas about their views—and their own right to lead—provides the

‘moral framework that justifies the murder of those perceived as opponents. Hun

‘ger and Hope contained some advance warning of this authoritarianism. Diaz

(1969:34-35) directed the book not to poor people in Ayacucho, but to “young

students and researchers” whom he hoped would recognize their “historical re-

sponsibility to study our problems and take an honest position in the search for

‘new situations."” While conserving a profound regard for peasant knowledge and

militancy, he also mixed in phrases about the “'miserable masses” and “illiterate

‘peasants” that suggested their political consciousness to be less acute than that of|

‘an educated vanguard, The people would be at the heart of the revolution. But

they would need to be organized in a “planned state” (1969:266).

On balance, though, Diaz’s vision had a collaborative flavor very different

from the dogmatism of the party he would help to organize in the next decade.

‘The sharp-sighted passion of the young professor had not yet hardened into doc-

trine. The University of Huamanga, Diaz (1969:265) wrote, should avoid becom-

MISSING THE REVOLUTION. &3

ing a “producer of egotists and individualists”” and “put itself at the service of

the collectivity."* But if it did not, Diaz (1969:24) believed Ayacucho’s poor

‘would make change on their own, “passing sooner or later right over [the uni-

versity], and transforming its world.” At the end of Diaz's (1969:266) vision was

‘a powerful yet strangely innocent dream of a collectively fashioned utopia. The

‘Andes have strong people and rich natural resources, he wrote in the last line of

‘Hunger and Hope—"let’s make them into a paradise.

Edward Said (1979:1) speaks of how the bloody civil war in Beirut of 1974—

175 crashed against the imagery of Orientalism. It was no longer so possible to

represent the Middle East as ‘a place of romance, exotic being, haunting mem-

cries and landscapes, remarkable experiences."" Ayacucho marked a similar mo-

ment for Andcanism, No longer could the highlands so easily support interpre-

tations where they appeared as a place of static cultures and discrete identities.

Colorful posters of Andean peasants in ponchos posed next to llamas at Macchu_

Picchu still adorned the walls of travel agencies across the United States. But a

different kind of image of the highlands also began to reach this country: pictures

‘of mass graves, wreckage from explosions, soldiers in black ski masks, and farm,

families mourning their dead.

Far from the paradise imagined by Diaz, life in much of Peru’s highlands has

become a nightmare. More than fifty thousand people fled the terror in the coun-

tuyside for Lima's slums over the 1980s (Kirk 1987). Senderistas murder not only

representatives of the state, but political candidates and trade unionists. Gover.

_ment security forces have made rape and torture into standard practice. They have

‘disappeared’ more than 3,000 people since 1982, and killed at least as many in

‘mass executions and selective assassination (Amnesty International 1989:1),

One casualty of war was Antonio Diaz Martinez. Arrested in the early 1980s,

the was one of the 124 prisoners in the terrorism wing of the cement-block Luri-

_gancho prison in the sandy hills on Lima's periphery. In June 1986, Senderistas

in Lurigancho, the island prison of El Front6n, and the women’s detention center

of Santa Barbara staged simultaneous takeovers to protest government plans 10

move them into a more secure facility. President Alan Garcia refused to negotiate

‘He tured the prisons over to the armed forces. The police stormed Santa Barbara,

killing two prisoners. At El Frontén, helicopters bombed the main pavilion.

‘Troops killed at least 90 prisoners. At Lurigancho, the police fired bazookas, mor-

tar, and rockets into the compound and then stormed the prison. Diaz was prob-

ably one of atleast one hundred prisoners executed after surrendering, shot inthe

hhcad or mouth as they lay flat on the ground (Amnesty International 1989:7). To

prevent autopsies, the security forces secretly buried the bodies at night in grave-

yards around Lima. Diaz’s body was discovered in a shallow grave in the Imperial

‘Cemetery in Cafete province, just south of the capital.

Just five weeks before the prison uprising, Diaz. gave one of the first inter-

views granted by a Shining Path leader. Journalist José Maria Salcedo (1986)

passed from the chaos of the regular prison into the special terrorist cellblock

St CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

where Senderistas maintained tight discipline, Salcedo attempted to paint Diaz as

«half-hearted revolutionary. He concentrated on the young guerrilla who super-

vised the interview. The prison transfer was already announced. Diaz foresaw that

the army might use opposition tothe transfer to justify a massacre, but professed

ro fear. “Our morale is superior and we take death as a challenge,” said Diaz

(quoted in Salcedo 1986:64).

In the end, however, the interview undermines Salcedo’s effort to depict

Diaz as less than committed to the Shining Path, For Diaz had clearly evolved

into a hard-tiner. The answers were still concise and smart. But they had the un-

‘compromising edge that had already emerged in Diaz’s second book, China: The

Agrarian Revolution (1978), Written after a 1974-75 stay in China and published

aa decade after Hunger and Hope, this book revealed Diaz’s turn to the inflexible

Maoism of the Cultural Revolution. "Since 1949... . the Dictatorship of the Pro-

letariat against the bourgeoisie had grown even more intense,”” Diaz (1978:8) be-

gan the book, “*. . . [and] with the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution the red

line of President Mao again becomes more vigorous." In Lurigancho, Diaz could

now give emphasis to his commitment to communism ("we are all material for

the transition to communism’) and cite the cold-blooded Abimael Guzmin—

“President Gonzalo” —as a maximum paragon of moral virtue (“the greatest af-

firmation of life over death”). The Shining Path must sometimes kill peasants, he

explained in good Maoist-Stalinist language, because “the countryside is not flat

but divided into classes.

As for anthropologists, most have retreated from Peru. Only a handful still,

work in the highlands, and none in Ayacucho’ countryside. Only one remains of

the more than ten major Andean archacology projects that operated at the end of

the 1970s, Graduate students interested in the Andes now opt for Ecuador or Bo-

livia

To my knowledge, the only Andeanist to offer written public reflections on

why anthropologists did not anticipate the Shining Path is Billie Jean Isbell. Her

short introductory note to a 1985 reprinting of To Defend Ourselves mixes a frank

admission of err with a confident rhetoric of continuing expertise. “My anthro-

pological perspective,”* she writes, “blinded me from seeing the historical pro-

cesses that were occurring atthe time. . . . did not adequately place Chuschi in

‘a world system in which increasing Violence and the breakdown of nation states

in the Third World are becoming commonplace’ (Isbell 1985:xii—niv)

But Isbell also conserves her Same vision of Andean continuity and self-con-

tainment. She does not consider how the growth of Sendero has reflected peasant

discontent or Peru's intensifying interconnections. Instead, she still speaks of an

“increasing polarization of the Quechua-speaking masses and the national cul-

ture" and depicts the Shining Path as a *'small leftist movement” external and

different from the peasantry:

Sendero Luminoso has declared that they are prepared fora fifty year strugele in order

to destroy the existing government and institute a new onder. ‘The peasants. on the

MISSING THE REVOLUTION. 8

‘ther hand, are concentrating on preserving their lands and their way of life. [Isbell

1985xii)

‘Of course, this position has partial ruth. It remains essential to understand that

Sendero is no organic peasant uprising. But Isbell overlooks that many of Sen-

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Legitimate ESA Letter - ESA DoctorsDocument5 pagesLegitimate ESA Letter - ESA DoctorsgabyNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- FINAL Chavez Ravine ProgramDocument8 pagesFINAL Chavez Ravine ProgramgabyNo ratings yet

- Flyer Fall 2023 First MeetingDocument1 pageFlyer Fall 2023 First MeetinggabyNo ratings yet

- Correa - The Flight CondorDocument9 pagesCorrea - The Flight CondorgabyNo ratings yet

- Flyer Fall 2023 First MeetingDocument1 pageFlyer Fall 2023 First MeetinggabyNo ratings yet

- Pak, Dystopia in DisguiseDocument19 pagesPak, Dystopia in DisguisegabyNo ratings yet

- Expenses CalculationDocument4 pagesExpenses CalculationgabyNo ratings yet

- Flyer Fall 2023 First MeetingDocument1 pageFlyer Fall 2023 First MeetinggabyNo ratings yet

- Frequently Asked Questions - I-20 - Office of Admissions and Recruitment - Uw-MadisonDocument3 pagesFrequently Asked Questions - I-20 - Office of Admissions and Recruitment - Uw-MadisongabyNo ratings yet

- Bardwell-Jones and McLaren, Introduction - To - Indigenizing - ADocument17 pagesBardwell-Jones and McLaren, Introduction - To - Indigenizing - AgabyNo ratings yet

- Flyer Fall 2023 First MeetingDocument1 pageFlyer Fall 2023 First MeetinggabyNo ratings yet

- Information About The Wisconsin Driver License (DL) Application (Form MV3001)Document3 pagesInformation About The Wisconsin Driver License (DL) Application (Form MV3001)gabyNo ratings yet

- Career Timeline For International StudentsDocument1 pageCareer Timeline For International StudentsgabyNo ratings yet

- The 5 Best Neighborhoods in Madison, WI To Move To Right Now - SpareFoot Moving GuidesDocument18 pagesThe 5 Best Neighborhoods in Madison, WI To Move To Right Now - SpareFoot Moving GuidesgabyNo ratings yet

- Before A New Roommate Moves In, The Leaseholder and Potential Roommate Must Complete and Submit A "Roommate AddDocument2 pagesBefore A New Roommate Moves In, The Leaseholder and Potential Roommate Must Complete and Submit A "Roommate AddgabyNo ratings yet

- How To Help An Adult Dog Adjust To A New Home - American Kennel ClubDocument16 pagesHow To Help An Adult Dog Adjust To A New Home - American Kennel ClubgabyNo ratings yet

- How To Certify An Emotional Support Dog - ESA DoctorsDocument13 pagesHow To Certify An Emotional Support Dog - ESA DoctorsgabyNo ratings yet

- (ORD) Chicago - (LIM) Lima: Friday, December 24 Saturday, January 22Document3 pages(ORD) Chicago - (LIM) Lima: Friday, December 24 Saturday, January 22gabyNo ratings yet

- Per Diem Calculation Sin DesayunoDocument1 pagePer Diem Calculation Sin DesayunogabyNo ratings yet

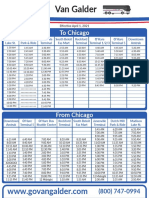

- Horarios Van GalderDocument1 pageHorarios Van GaldergabyNo ratings yet

- Per Diem CalculationDocument1 pagePer Diem CalculationgabyNo ratings yet

- Consent and Cameras in The Great Digital PivotDocument8 pagesConsent and Cameras in The Great Digital PivotgabyNo ratings yet

- The Theatre Industry's Essential Workers: Catalysts For ChangeDocument15 pagesThe Theatre Industry's Essential Workers: Catalysts For ChangegabyNo ratings yet

- The Smell: Joshua Williams Theatre Topics, Volume 31, Number 2, July 2021, Pp. 195-198 (Article)Document5 pagesThe Smell: Joshua Williams Theatre Topics, Volume 31, Number 2, July 2021, Pp. 195-198 (Article)gabyNo ratings yet

- Privileged Spectatorship: Theatrical Interventions in White Supremacy by Dani Snyder-Young (Review)Document3 pagesPrivileged Spectatorship: Theatrical Interventions in White Supremacy by Dani Snyder-Young (Review)gabyNo ratings yet

- Chicago (ORD) : Search HotelsDocument8 pagesChicago (ORD) : Search HotelsgabyNo ratings yet

- Chicago (ORD) : Search HotelsDocument4 pagesChicago (ORD) : Search HotelsgabyNo ratings yet

- Datcher Heroes and Hieroglyphics of The FleshDocument31 pagesDatcher Heroes and Hieroglyphics of The FleshgabyNo ratings yet

- September 8 - December 15: Group Fitness ScheduleDocument1 pageSeptember 8 - December 15: Group Fitness SchedulegabyNo ratings yet

- Chicago (ORD) : Search HotelsDocument8 pagesChicago (ORD) : Search HotelsgabyNo ratings yet