Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Socrates and The Divine Signal According To Plato's Testimony: Philosophical Practice As Rooted in Religious Tradition

Uploaded by

Francisco VillarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Socrates and The Divine Signal According To Plato's Testimony: Philosophical Practice As Rooted in Religious Tradition

Uploaded by

Francisco VillarCopyright:

Available Formats

Socrates and the Divine Signal

according to Plato's Testimony:

Philosophical Practice as Rooted in

Religious Tradition

Luc Brisson

In the Platonic corpus, we find some passages in which the divine signal

manifested to Socrates is mentioned: Apology 31c-e, 40a, 40c, 41d; Euthy-

phro 3b; Euthydemus 272e; Republic VI 496c; Phaedrus 242b-c; Theaetetus

151a. This phenomenon is also mentioned in the first Alcibiades 103a-b,

105d-e, 124c-d, whose authenticity I consider doubtful, and in the Theages

128d-31a, which I consider apocryphal. I will not take these last testimo-

nies into consideration, and I will limit myself here to a description of

the phenomenon in which this divine signal consists, to raise a more

general problem: that of the compatibility, in Socrates, between this

divine signal and 'moral autonomy'.1

1 The Signal

What reaches Socrates is a semeion: Ap 40bl, 40c3,41d6; Euthd 272e4; Phdr

242b9; R VI 496c4. Formed from sema, 'sign, distinctive character, or

mark', the word semeion designates both a sign by which one recognizes

something or someone (a trident for Poseidon, for example), and a signal,

1 This term is not found as such in ancient Greece: the terms autonomia and autonomes

are applied to cities and not to human beings. Following Kant, I understand moral

autonomy as the ability to determine one's actions by means of reason alone.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

2 Luc Brisson

that is, a sign that serves as a warning and triggers specific behavior —

the response — once conditioning has been activated. In principle, this

sign may involve all five senses. Sometimes, however, the nature of the

signal perceived by Socrates is specified: It is a phone: Ap 31d3; Phdr

242c2. A phone involves hearing, for the term phone designates a sound

produced by a living being. Unlike logos, however, this sound is not

necessarily articulated.2 Only the acoustic aspect of the phenomenon is

taken into consideration. The divinity manifests itself to Socrates not

directly or in person, but indirectly, by a phonic signal that manifests a

prohibition. What is more, in view of all that has just been said, such a

signal should be equivalent to something like 'nie', 'do not'. There can

therefore be no question of a revelation, in this context. In a revelation

we find, among other things, descriptions, arguments, and injunctions,

and this implies the use of articulated language.

2 The Sender

The signal addressed to Socrates is qualified either as theion (Ap 31c8), or

as daimonion (Ap 31dl; Euthd 272e4; Euthphr 3b5; Phdr 242b9; R VI 496c4).

The adjective theion indicates that the signal is sent by a theos. This is

confirmed by Ap 40bl, where ίο tou theou semeion is mentioned. As far as

the adjective daimonion is concerned, we must, I believe, refrain from

making it into a substantivized adjective, even when daimonion is pre-

ceded by to as in Euthyphro 3b5, in Theaetetus 151a4,3 and in Apology 40a4.

In all these cases, to daimonion seems to me to be an ellipse for to daimonion

semeion.4

2 We read at the beginning of Aristotle's Politics: 'As we say, indeed, nature does

nothing in vain; yet man is the only living being (zoiori) to have speech (logon). To

be sure, the sound of the voice (phone) expresses pain and pleasure; thus we find it

in living beings generally (Ms allois zoiois): their nature only allows them to feel pain

and pleasure and to manifest them among themselves. But speech (logos), for its

part, is made to express what is useful and harmful, and consequently also what is

just and unjust' (Pol 11,1253a9-15).

3 For an objection, see MacNaghten 1914,188.

4 An inventory of the various positions on that point may be found in Dorion 2003,

171 η 7, who refers to note 5; Dorion adopts the position that the expression to

daimonion is equivalent to ho theos, or to to theion. As far as Plato is concerned, my

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

Socrates and the Divine Signal 3

I base this hypothesis on the following two arguments. (1) In most

cases, to daimonion is constructed with the verb gignesthai followed by a

first-person personal pronoun in the dative. But such a construction

quite naturally implies that the subject of the verb is a phenomenon and

not a person.5 In Euthyphw 3b5 and in Theaetetus 151a4, we must under-

stand that it is not the divinity that manifests itself in person, but instead

that it reveals a prohibition through the intermediary of a sign. (2) Above

all, only this hypothesis enables us to understand Apology 40a4 without

modifying the text transmitted by the manuscripts.6 The manuscripts

read he gar eiothuia moi mantike he tou daimoniou. Since mantike is an

adjective and eiothuia is a perfect passive participle, we must suppose

that a noun is understood. With mantike, what is understood is usually

tekhne, which gives the translation: 'the divinatory art (or simply divina-

tion), that is familiar to me'. This way of construing things immediately

raises two problems. The following clause, he tou daimoniou becomes

quite problematic, for we must understand 'the divinatory art (or divi-

nation) that comes from the daimonion' or 'the divinatory art (or divina-

tion) that pertains to the daimonion'; which makes no sense in either case.7

This, moreover, is why Schleiermacher wanted to athetize he tou daimo-

niou. In fact, if we understand phone after mantike and semeiou after

daimoniou, the meaning becomes clear without any need for eliminating

anything, for, we can then translate while considering tou daimoniou as

an objective genitive: 'the divinatory voice that is familiar to me, the one

in which the divine signal consists'.8

In none of the texts mentioned, it seems to me, is a clear distinction

made between the notion of theos and that of daimon, although the

position is akin to that of Vlastos 1991, add note 6.1,280-7, who relies on Burnet. I

am willing to admit, with Dorion, that when in Xenophon we find the expression

to daimonion semainein, this expression would be redundant if to daimonion were an

ellipse for to daimonion semeion (as Dorion explains at note 11 of page 173). Things

are different in Plato, whose strategy is quite distinct when it comes to defending

Socrates' memory (see Dorion 2003,158 n 57).

5 As is noted by Dorion 2003,182 n 39.

6 For a review of the positions, see Dorion 2003,183 n 43.

7 On the difference between Plato and Xenophon on the question of divination, see

Dorion 2003,186-7.

8 This position is very close to that of McPherran 1996,185 and 195.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

4 Luc Brisson

distinction is clear in other passages of the Platonic corpus.9 This confu-

sion gives a good reflection of the ambiguity we observe at the time in

the Greek religious tradition between theos and daimon.10 This raised no

problems in the context of a civic religion without clergy and without a

reference text to serve as the vehicle of precise dogmas. As a result, there

is nothing to oppose translating both theion and daimonion by 'divine'.

What is more, no information is given on the identity of the theos or the

daimon who intervenes in the case of Socrates. We can therefore not

associate with Socrates a theos or a daimon, who would play the role of

a guardian angel or tutelary divinity.11 The signal could have been sent

to Socrates by Apollo or by any other divinity of the traditional pan-

theon. If we limit ourselves to the texts considered here, we cannot say

anything more.

3 The Addressee

The most usual construction for speaking of the transmission of this

signal is moi gignetai, which could be translated as 'it happens to me', 'it

reaches me', or 'X manifests itself to me': Ap 31c8-dl, 31d3; Euthd 272e3;

9 For instance, in the Apology and the Symposium. For a critical inventory, see A. Motte

1989,205-21; 208 n 7 (220-1).

10 Motte is quite right to write: 'As a matter of fact, the Greeks never had a very firm

conception on the subject of the nature and origin of demons' (Motte 1989,208).

11 The interpretation of the daimonion as a guardian angel is still frequent today (cf.

Gottlieb 2000,20 and 28). It was upheld in particular by Motte 1989, in the following

terms: "This conception [sci'i. that of the demon-phylax], which is akin to that of the

guardian angel, is also attested in several passages of the Laws, and it is to it, of

course, that it is fitting to attach the famous theme of the of Socrates' demoniacal

sign' (213). My disagreement with this position bears on two points: (1) the demon-

phylax of the Phaedo and the Republic bears no resemblance to a guardian angel: it is

not there to watch over us, protect us, and help us avoid making mistakes, but

essentially to ensure that the cup will be drunk to the dregs; that is, that the destiny

we have chosen will be accomplished entirely; (2) Motte already assimilates Socra-

tes' divine sign to a form of demon, or again of guardian angel. But the divine sign

has nothing in common with the demon of the Phaedo and the Republic; on the other

hand, it is true that it is the manifestation of a certain divine benevolence (like the

guardian angel), but it does not have the independence of a demon.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

Socrates and the Divine Signal 5

Euthphr 3b6; Phdr 242b9, 242c2.12 The impersonal construction empha-

sizes the objective, and as it were automatic nature of the intervention.13

Socrates never takes the initiative, and never solicits the signal. The

signal somehow 'falls upon him', without his expecting it This signal

concerns a particular individual, Socrates, as is indicated by the construc-

tion with the dative of a personal pronoun (moi), indicating the benefici-

ary of the action.

In Book VI of the Republic, Socrates' exceptional character in this

regard is insisted upon:

As far as I am concerned, the divine signal (to daimonion semeion) is not

worth talking about; it's not certain that we could find another individ-

ual to whom it has manifested itself (e tini allöi e oudeni gegonen") among

people of the past (tö« emprosthen). (R VI 496c3-5).

Socrates has experienced this signal since childhood (Ap 31d3).

Throughout his life, until the day of the trial he had to face, these

interventions have never ceased (aei) (Ap 40a5); they occurred very close

to one another (pukrie15) (Ap 40a5), on every occasion (ekastote), and they

concerned even little things (Ap 40a6). We can therefore understand why

Socrates calls this signal 'familiar' (ewthos) (Ap 40c2; Euthd 272e3; Phdr

242b9).

4 Nature and Context of the Manifestation

The divine signal always manifests itself in a concrete situation, and it

informs Socrates about the opportunity to undertake a particular action

that is in itself banal. It therefore has no theoretical dimension, nor does

it, by itself, permit any considerations of a general nature. To be sure, the

context of the prohibition may make the simplest of divine prohibitions

of the simplest of actions extremely significant. For instance, just as the

12 On this expression, see Dorion 2003,182 n 30.

13 For a different position, see Dorion 2003,182 n 39.

14 Note the recurrence in this phrase of the habitual construction with gegonen in the

dative.

15 In Greek, pukrie, which in the proper sense means 'compact', 'thick', 'dense'.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

6 Luc Brisson

divine signal did not prevent Socrates from going to Court on the day of

his trial, when he was to be condemned to death, this sign could have

prevented Socrates from going to the Assembly at a given crucial mo-

ment, which could have opened the doors for him to a political career.

In both cases, however, it is the interpretation Socrates gives after the

fact that gives meaning to the signal's manifestation or absence.

4 1 Either the signal manifests itself

When it manifests itself, the signal limits itself in every case (aei) to a

prohibition: it diverts (apotrepei) Socrates from pursuing an action, in the

order of speech and activity, that he is about to undertake (Ap 31d3-4);

it holds him back (episkhei) from acting (Phdr 242cl); it prevents him

(apoköluei) (Tht 151a4); it does not allow him to act (ouk eai) (Phdr 242c2);

it opposes him (enantioutai) (Ap 40a-c, iris). From what action does the

divine signal divert Socrates? Sometimes, it makes him remain silent (Ap

40b4). In the Euthydemus (272e) and in the Phaedrus (242d), it stops him

from getting up and leaving. It prevents him from seeing again some of

his disciples who left him some time ago (Tht 151a). It keeps him from

doing politics (R VI 496c; Ap 40a-b). In all these cases, the signal diverts

Socrates from occupations to which no moral value is attached: instead,

the moral value of these occupations depends on the interpretation

Socrates gives to it after the fact. It is Socrates who, later on, will consider

that it was better for him not to undertake the prohibited action. We

therefore cannot consider that the signal perceived by Socrates might be

equivalent to a form of moral conscience.16

4 2 Or else the signal does not manifest itself

At the end of the Apology, Socrates gives the following interpretation of

the god's silence. Commenting to his friends on the result of the trial,

Socrates says:

16 Hadot 2002,34, writes with regard to the daimonion: 'Mystic experience or mythical

image, it is hard to say; but in any case we can see in it a kind of figure of what would

later be called the moral conscience'. This is highly debatable, for the divine sign

intervenes very often, as Socrates himself admits, on insignificant occasions that

have no moral dimension. The sign would be a moral conscience if it intervened to

prevent Socrates from doing evil; but such is not the case.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

Socrates and the Divine Signal 7

Yes, judges — and when I call you "judges", I am using the proper

formula17 — something amazing happened to me. In fact, whereas the

divinatory voice that is familiar to me (he gar eiothuia moi manlike), that

in which the divine signal consists (he tou daimoniou), has never ceased

manifesting itself to me until today (en men toi prosthen khronoi panti

panu pukne aei en) to prevent me (enantioumene), even in matters of little

importance (kai panu epi smikrois),™ from doing what I shouldn't do,

today, as you can observe yourselves, there occurred to me what could

be considered the greatest evil (oietheie eskhata kakon einaf) and which is

thought to be so (kai nomizetai). And yet, the divine signal (to tou theou

semeion) did not hold me back (enantwthe) either this morning, when I

was leaving my home, nor in the moment when here, before the

tribunal, I was going up to the tribune, nor during my plea, to prevent

me from saying anything. Quite often, in other circumstances, it has

silenced me right in the middle of my speech (kaitoi en allots logois

pollakhou de me epeskhe legonta metaxu). Today, on the contrary, in the

course of this affair, it never prevented me from doing or saying

anything. What reason must I suppose to explain this phenomenon? I

will tell you. What is happening to me might well be a piece of good

fortune for me, and we all — all of us who are present — are mistaken

when we imagine that to die is an evil. A decisive proof of this for me

(mega moi tekmerion) is the following: indeed, it would not have been

possible that the signal that is familiar to me (to eiothos semeion) did not

oppose me (ouk enantwthe an moi), if what I was going to do was not a

good thing (agathon)." (Ap 40a2-c2).

In this passage, we encounter the usual description of the signal's

manifestation. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that Socrates pro-

poses an evaluation of what has just happened to him. Whereas most

people consider that the death to which he has just been condemned is

the worst of evils, he, for his part, considers that, in view of the fact that

17 In fact, Socrates is no longer speaking to those who voted to acquit him, and thus

expressed a proper judgment, in accordance with the judgment that must charac-

terize a judge; cf. the beginning.

18 For examples, cf. Euthydemus 272e; Phaedrus 242b.

19 For the interpretation of this passage, see Dorion (2003), 183, nn 43 to 46; see also

the passage from Phaedo 85b.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

8 Luc Brisson

the signal has not held him back from going to the trial at the end of

which he was condemned to death, death must be something good for

him.

The reading of this passage has led some interpreters to conclude that

Socrates was contradicting himself. Whereas above (Apology 29a4-b2 and

37b5-7), he affirmed that he did not know whether death was a good

thing, Socrates declares here that what is happening to him because of

the absence of a divine signal — that is, death — is a good thing. T. C.

Brickhouse and N. D. Smith20 admit in any case that Socrates is mistaken

when he concludes that, for him, what is not an evil is necessarily good.

If he interprets the lack of manifestation of the divine signal in this way,

that means that Socrates considers that what is not an evil is good,

according to the following reasoning. If what I was going to do was a

bad thing, the signal would have prevented me from doing it. It did not

prevent me from doing it. Therefore, what I did was a good thing. Such

a conclusion is not essential, for nothing indicates that that which is not

a bad thing is a good thing; it can be a ridiculous thing, an insignificant

thing, or an indifferent thing, that is, something neutral.21 For his part,

Mark A. Joyal22 considers that the difficulty can be explained by a literary

stratagem on the part of Plato, who wanted to assimilate the divine signal

to conventional religious phenomena, which would, in a way, have

justified the accusers.

5 The Religious Background

For my part, I think Socrates does not contradict himself in the Apology,

and Plato never described Socrates as bogged down in this contradiction,

even for requirements of a literary nature. Against this view, I would

adduce the following two reasons.

• Even if he is not in a position to say whether death in general is or

is not a good thing, Socrates can consider that in the particular

20 Brickhouse and Smith 1989, section 5.5

21 For an example, see Gorgias 467el-8a6.

22 Joyal 1997,43-58

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

Socrates and the Divine Signal 9

circumstances in which he finds himself, the result of a trial that

condemns him to death is for him (hie et nunc) a good thing.

• Socrates is immediately situated in a religious context which, con-

sciously or unconsciously, contemporary commentators do not take

into consideration. Let us read the following passage once again,

which we find at the very end of the Apology, and which reflects the

one we have just cited like a mirror.

You too, judges, must be full of confidence in the face of death,23 and

put one single truth in your minds to the exclusion of all others, that is,

that no evil can touch a good man24, either during his life or after his

death,25 and that the gods do not lack interest in his fate (oude ameleitai

hupo theon ta toutou pragmata). Nor is the fate that is mine today a result

of chance (oude ta emu nun apo tou automatou gegonen); on the contrary,

I consider it obvious that it was better for me to die now and be freed

from all problems. This indeed is why (dia touto kai) the signal (to

semeion) did not hold me back at any time (erne oudamou apetrepsen),26

and as a result I am absolutely not upset with those who have con-

demned me by their vote. (Ap 41c8-d7).

This is the general context that enables Socrates to interpret in a

positive sense the fact that the signal does not manifest itself at his trial.

What does this mean? Socrates bases the belief that 'no evil can touch a

good man, either during his life or after his death' on the following

principle: 'the gods do not lack interest in the fate of human beings'.27

Consequently, Socrates can claim not to know anything about death or

anything else, and he can interpret the result of the trial, which implies

death, as a good thing. In fact, the only minimal knowledge he admits

to possessing is the following:

23 For the same expression, cf. Phaedo 63c.

24 Socrates knows that he is a good man, because he has never committed an injustice

by disobeying the gods (see the following citation from Ap 29b6-7).

25 We find an echo of the same doctrine in Book X of the Republic (613a).

26 This certainty is expressed and demonstrated in Book X of the Laws.

27 Cf. Apology 40d2.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

10 Luc Brisson

What I do know, on the other hand (oida), is that committing injustice

(to adikein), that is, disobeying (kai apeitheiri) what is worth more than

oneself (beltioni), whether god (kai theöi) or human being (kai anthropoi),

is something bad, and shameful. It follows that before the fear of evils

that I know are evils, I will never range fear of things of which I do not

know whether they are good, and I will not try to avoid them, either.

(Ap 29b6-cl)

We can thus understand that Socrates considers himself a good man,

to whom nothing bad can happen. The knowledge in question refers not

to an item of information, but to a belief. This belief in turn takes its place

within a wider context, which implies a hierarchy. Gods and demons are

more powerful than the human beings for whom they care, and among

human beings an expert is superior, by reason of his positive knowl-

edge.28 Even if he cannot find genuine experts, Socrates is warned by a

divinity not to do such-and-such a thing; consequently, he can interpret

a non-prohibition not as permission, but as proof that that action he

proposes will not entail bad consequences for him. Hence, three conse-

quences follow:

(1) Rational exegesis of the divine signal, which is always proposed

at Socrates' initiative, admits as an axiom the well-foundedness

of divine action.

(2) The gods never send inexplicable signals.

(3) In this context, Socrates can, without any hesitation, consider

that the death to which he is condemned at the end of his trial is

a good thing for him, without knowing how he should react to

the general question of whether death is the greatest of evils. The

divine signal always manifests itself as a replacement for defec-

tive knowledge; but philosophy according to Socrates is nothing

other than ignorance that is not ignorant of itself.

28 This belief is also expressed by Xenophon in his Memorabilia (14,14-15 and IV 3,12).

Both passages are cited by Dorion 2003,175-6.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

Socrates and the Divine Signal 11

6 The Question of 'Moral Autonomy'

I conclude with a few remarks intended to set forth on what conditions

the divine signal's manifestation to Socrates can, in my view, be compat-

ible with the use of reason in moral matters.

(1) The gods exist, and are more powerful than human beings.

(2) They are concerned with the fate of all human beings; they

reward the good and punish the wicked.

(3) Socrates is the object of exceptional attention on the part of the

gods, as is indicated by the manifestation of the divine signal.

Moreover, this explains the accusation concerning kaina daimo-

nia brought against him.

(4) The signal does not come within the domain of articulated

discourse; there can therefore be no question of a revelation, or

even an explanation.

(5) Socrates never solicits the manifestation of this signal, but it

imposes itself upon him. We therefore cannot speak of a per-

sonal relation between Socrates and the sender of the signal,

which never manifests itself directly.

(6) When it manifests itself, the signal indicates only one thing to

Socrates: the prohibition to begin or to pursue such-and-such a

concrete action. Conversely, the signal's failure to manifest itself

can be interpreted by Socrates as proof that such-and-such a

concrete action will not entail anything bad for him.

(7) The concrete action in question has no moral value in itself. This

moral significance is given to it after the fact by Socrates.

(8) The divinity does not say whether such-and-such an action,

abandoned or undertaken, is good or bad. It restricts itself to

sending or failing to send a signal. The divinity thus does not

teach Socrates anything, and he can thus lay claim to complete

ignorance.

(9) It is Socrates who, in some cases, attributes a value to the action

abandoned or undertaken. The very possibility of this exegesis

explains why Socrates seeks to know what virtue is.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

12 Luc Brisson

No one can deny that Socrates uses his reason in the area of morals.

In him, however, rational activity is framed by divine intervention,

which fixes its limits and orients it. The divine signal enables Socrates to

determine in every particular case if he can do or say something, and as

a function of these injunctions he tries, by applying the usual rules of

deduction, to produce general propositions that give a rational account

of adequate behaviors. In Socrates, religious tradition gives its frame-

work to the practice of philosophy, without, however, being substituted

for it. Socrates does not enjoy complete 'moral autonomy', but neither is

he a blind follower of the religious tradition in which he is immersed29.

The trial that had him condemned to death testifies to the validity of the

second proposition, whereas the divine signal testifies to the validity of

the first one.

29 This conclusion is not that far from the position of Brickhouse and Smith 2000b.

Brought to you by | University of Minnesota

Authenticated | 160.94.45.157

Download Date | 10/1/13 1:43 AM

You might also like

- John M. Rist - Plotinus and The "Daimonion" of SocratesDocument13 pagesJohn M. Rist - Plotinus and The "Daimonion" of SocratesM MNo ratings yet

- Chase Porphyry On The Cognitive Process Ancient Phil 2010-LibreDocument23 pagesChase Porphyry On The Cognitive Process Ancient Phil 2010-LibreJohnette RicchettiNo ratings yet

- Uwe Wirth - Derrida and Peirce On IndeterminacyDocument10 pagesUwe Wirth - Derrida and Peirce On IndeterminacyVivi SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Carpenter Phileban GodsDocument20 pagesCarpenter Phileban GodsEsteban F.No ratings yet

- Angels As Arguments The Rhetorical Funct PDFDocument8 pagesAngels As Arguments The Rhetorical Funct PDFIswadiPrayidnoNo ratings yet

- 007 02 s006 TextDocument3 pages007 02 s006 TextblavskaNo ratings yet

- Daniele TheaetetusDocument19 pagesDaniele TheaetetusMarcelo G. DiasNo ratings yet

- Plotinus' Demonological IdeasDocument10 pagesPlotinus' Demonological Ideasdquinn9256No ratings yet

- Eikos MythosDocument23 pagesEikos MythosGGocheveNo ratings yet

- What IsDocument7 pagesWhat IsRandolph DibleNo ratings yet

- Plato's Theory of Knowledge: The Theaetetus and the SophistFrom EverandPlato's Theory of Knowledge: The Theaetetus and the SophistRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Dorion Plato On Enkrateia PDFDocument20 pagesDorion Plato On Enkrateia PDFIván GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Reading philosophical-patristic of John 1,2-3 in the comment to John of Origen II, 4,34-15,111From EverandReading philosophical-patristic of John 1,2-3 in the comment to John of Origen II, 4,34-15,111No ratings yet

- 07 Merold Westphal - Abraham and Sacrifice (2008)Document13 pages07 Merold Westphal - Abraham and Sacrifice (2008)madsleepwalker08No ratings yet

- The Seventh Chamber: A Commentary on "Parmenides" Becomes a Meditation On, at Once, Heraclitean "Diapherein" and Nachmanian "Tsimtsum"From EverandThe Seventh Chamber: A Commentary on "Parmenides" Becomes a Meditation On, at Once, Heraclitean "Diapherein" and Nachmanian "Tsimtsum"No ratings yet

- Double Daimon in EuclidesDocument13 pagesDouble Daimon in EuclidesAngela Marcela López RendónNo ratings yet

- Iii.-Ambiguity.: B Y Richard RobinsonDocument16 pagesIii.-Ambiguity.: B Y Richard RobinsonFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- He Stir Truth SophistDocument24 pagesHe Stir Truth Sophistrodrdc2011No ratings yet

- The Being of the Beautiful: Plato's Theaetetus, Sophist, and StatesmanFrom EverandThe Being of the Beautiful: Plato's Theaetetus, Sophist, and StatesmanRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (113)

- Immortality and The Nature of The Soul in The Phaedrus PDFDocument27 pagesImmortality and The Nature of The Soul in The Phaedrus PDFAlex Madis100% (1)

- A Note Concerning Aristotle, Reason, and VirtueDocument3 pagesA Note Concerning Aristotle, Reason, and VirtueMyndianNo ratings yet

- I Timothy 4Document33 pagesI Timothy 4ronsnider1No ratings yet

- After The AscentDocument14 pagesAfter The Ascenthieratic_headNo ratings yet

- Our Concern Though Is Not To Be Out of Sin But To Be God - Assimilation To God According To Plotinus - Thomas VidartDocument15 pagesOur Concern Though Is Not To Be Out of Sin But To Be God - Assimilation To God According To Plotinus - Thomas VidartAqil ShamilNo ratings yet

- The History of Divination As A General PhenomenonDocument30 pagesThe History of Divination As A General PhenomenonalisdorfNo ratings yet

- Ancient Greek TermsDocument19 pagesAncient Greek TermsJennifer LeQuireNo ratings yet

- Through A Glass Darkly I Corinthians 13Document5 pagesThrough A Glass Darkly I Corinthians 13Robert FrippNo ratings yet

- Theaetetus Sits Theaetetus Flies OntologDocument20 pagesTheaetetus Sits Theaetetus Flies OntologLau MorraNo ratings yet

- Who Is The Demiurge According To PlutarchDocument14 pagesWho Is The Demiurge According To PlutarchallyonionNo ratings yet

- Syzygies, Twins, and Mirrors - Stang, Charles M.Document38 pagesSyzygies, Twins, and Mirrors - Stang, Charles M.Pricopi Victor0% (1)

- Marsilio Ficino On The Triad Being-Life-Intellect and The Demiurge: Renaissance Reappraisals of Late Ancient Philosophical and Theological DebatesDocument35 pagesMarsilio Ficino On The Triad Being-Life-Intellect and The Demiurge: Renaissance Reappraisals of Late Ancient Philosophical and Theological DebatesKornél SzécsiNo ratings yet

- Concerning Empedocles, Heraclitus, and AristotleDocument19 pagesConcerning Empedocles, Heraclitus, and AristotlenadaraNo ratings yet

- Proclus On The Climax of The Phaedrus (247c6-d1) (Fortier, 2020)Document20 pagesProclus On The Climax of The Phaedrus (247c6-d1) (Fortier, 2020)Prometheus AlberioneNo ratings yet

- BURKERT (Air-Imprints or Eidola. Democritus' Aetiology of Vision)Document13 pagesBURKERT (Air-Imprints or Eidola. Democritus' Aetiology of Vision)manuel hazanNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Hellenic StudiesDocument7 pagesThe Journal of Hellenic StudiesNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Immortality and The Nature of The Soul in The PhaedrusDocument27 pagesImmortality and The Nature of The Soul in The Phaedrusvince34No ratings yet

- Signification and Denotation From Boethius To Ockham.Document30 pagesSignification and Denotation From Boethius To Ockham.JuanpklllllllcamargoNo ratings yet

- Landry Aaron J 2014 PHDDocument207 pagesLandry Aaron J 2014 PHDKATPONSNo ratings yet

- Dillon J., Intellect and The One in Porphyry's Sententiae, IJPT IV, 2010Document9 pagesDillon J., Intellect and The One in Porphyry's Sententiae, IJPT IV, 2010Strong&PatientNo ratings yet

- Davis Review of BenardeteDocument10 pagesDavis Review of Benardetesyminkov8016No ratings yet

- PhA 033 - Calcidius - On Demons PDFDocument80 pagesPhA 033 - Calcidius - On Demons PDFVetusta Maiestas100% (2)

- Why Plato Wrote The EpinomisDocument25 pagesWhy Plato Wrote The EpinomisJay KennedyNo ratings yet

- Review SEGAL Dionysian Poetics and Euripides' BacchaeDocument5 pagesReview SEGAL Dionysian Poetics and Euripides' Bacchaemegasthenis1No ratings yet

- MNP - Greek Texts For TranslationDocument6 pagesMNP - Greek Texts For TranslationJorge Juanca IlliaNo ratings yet

- Philo Prefinals ReviewerDocument2 pagesPhilo Prefinals ReviewerNix De La RosaNo ratings yet

- The Socratic ParadoxesDocument19 pagesThe Socratic ParadoxesVuk KolarevicNo ratings yet

- PDF 1 Sin Veil Shadow HadesDocument19 pagesPDF 1 Sin Veil Shadow HadesShey RoseNo ratings yet

- Parmenides and Sense-PerceptionDocument20 pagesParmenides and Sense-Perceptionvince34No ratings yet

- Tregu I Drogës 2019Document260 pagesTregu I Drogës 2019Anonymous evfIqW1t0No ratings yet

- Vida Anónima y Escolios Antiguos A La Obra de Isócrates (Isócrates P. 118)Document188 pagesVida Anónima y Escolios Antiguos A La Obra de Isócrates (Isócrates P. 118)Francisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Assessment Sensitivity Relative Truth and Its ApplicationsDocument361 pagesAssessment Sensitivity Relative Truth and Its ApplicationsFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Gill 1 PDFDocument16 pagesGill 1 PDFEduardo CharpenelNo ratings yet

- Swanson, Socratic and The Resolution of Fallacy in Platos EuthydemusDocument386 pagesSwanson, Socratic and The Resolution of Fallacy in Platos EuthydemusmartinforcinitiNo ratings yet

- American Philological Association: The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument8 pagesAmerican Philological Association: The Johns Hopkins University PressFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Gaps Gluts FuzzinessDocument28 pagesGaps Gluts FuzzinessFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Biografías Griegas (Isócrates, 280)Document531 pagesBiografías Griegas (Isócrates, 280)Francisco VillarNo ratings yet

- The Dark Enlightenment, Part 1 (Nick Land)Document6 pagesThe Dark Enlightenment, Part 1 (Nick Land)Francisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Brought To You by - University of South Carolina Libraries Authenticated - 129.252.86.83 Download Date - 7/20/13 6:34 AMDocument6 pagesBrought To You by - University of South Carolina Libraries Authenticated - 129.252.86.83 Download Date - 7/20/13 6:34 AMFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- 2004 BookMatter AnalysesOfAristotleDocument11 pages2004 BookMatter AnalysesOfAristotleFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Paideia The Ideals of Greek Culture Volume III The Conflict of Cultural Ideals in The Age of Plato PDFDocument383 pagesPaideia The Ideals of Greek Culture Volume III The Conflict of Cultural Ideals in The Age of Plato PDFFrancisco Villar100% (1)

- Kent Sprague R. (1972), The Older Sophists PDFDocument178 pagesKent Sprague R. (1972), The Older Sophists PDFFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Chance T.H. (1992), Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not PhilosophyDocument139 pagesChance T.H. (1992), Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not PhilosophyFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Bruno Breitmeyer-Blindspots - The Many Ways We Cannot See-Oxford University Press, USA (2010) PDFDocument281 pagesBruno Breitmeyer-Blindspots - The Many Ways We Cannot See-Oxford University Press, USA (2010) PDFFrancisco Villar100% (1)

- Gaps Gluts FuzzinessDocument28 pagesGaps Gluts FuzzinessFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Gisela Striker-Essays On Hellenistic Epistemology and Ethics-Cambridge University Press (1996)Document355 pagesGisela Striker-Essays On Hellenistic Epistemology and Ethics-Cambridge University Press (1996)Francisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Gisela Striker-Essays On Hellenistic Epistemology and Ethics-Cambridge University Press (1996)Document355 pagesGisela Striker-Essays On Hellenistic Epistemology and Ethics-Cambridge University Press (1996)Francisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Iii.-Ambiguity.: B Y Richard RobinsonDocument16 pagesIii.-Ambiguity.: B Y Richard RobinsonFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Simon Goldhill The End of Dialogue in Antiquity 2009Document276 pagesSimon Goldhill The End of Dialogue in Antiquity 2009Ruixuan Chen100% (1)

- Mytho HistoryDocument21 pagesMytho HistoryFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)Document935 pagesVuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)krca100% (2)

- (Untersuchungen Zur Antiken Literatur Und Geschichte Bd. 115) Sermamoglou-Soulmaidi, Georgia-Playful Philosophy and Serious Sophistry - A Reading of Plato's Euthydemus-De Gruyter (2014)Document213 pages(Untersuchungen Zur Antiken Literatur Und Geschichte Bd. 115) Sermamoglou-Soulmaidi, Georgia-Playful Philosophy and Serious Sophistry - A Reading of Plato's Euthydemus-De Gruyter (2014)Francisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Narcy M., Dialectic With and Without SocratesDocument12 pagesNarcy M., Dialectic With and Without SocratesFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Chance T.H. (1992), Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not PhilosophyDocument139 pagesChance T.H. (1992), Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not PhilosophyFrancisco VillarNo ratings yet

- Arte de Gorgias PDFDocument15 pagesArte de Gorgias PDFMarta RojzmanNo ratings yet

- Plato and The Mass Media (By Alexander Nehamas)Document21 pagesPlato and The Mass Media (By Alexander Nehamas)Sergio LopezNo ratings yet

- Mision Politica de Gorgias PDFDocument6 pagesMision Politica de Gorgias PDFMarta RojzmanNo ratings yet

- Fiqih Warisan-1 DR Muhammad Yusuf Siddik MADocument4 pagesFiqih Warisan-1 DR Muhammad Yusuf Siddik MAiwan nirwanaNo ratings yet

- Pinaveerabhadrudu Pillalamarri ( 14th Century AD) : October 2010Document3 pagesPinaveerabhadrudu Pillalamarri ( 14th Century AD) : October 2010harsha chakilamNo ratings yet

- Mix FictionDocument87 pagesMix FictionCrisNo ratings yet

- New Commentary On The (1983) C - Beal, John P. & Coriden, James - 7252-1-26Document26 pagesNew Commentary On The (1983) C - Beal, John P. & Coriden, James - 7252-1-26chipessenceNo ratings yet

- Session 3 - Tantrayukti History and PracticeDocument24 pagesSession 3 - Tantrayukti History and PracticeJohn KAlespi100% (1)

- Epic Destinies Part 1Document9 pagesEpic Destinies Part 1No Thank YouNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egypt Knew No Pharaohs Nor Any Israelites - PyramidionDocument90 pagesAncient Egypt Knew No Pharaohs Nor Any Israelites - PyramidionRegino Joel B. Josol86% (7)

- Gilgamesh Essay 1st HalfDocument4 pagesGilgamesh Essay 1st HalfFaith ShaferNo ratings yet

- History of Swinng TimelineDocument2 pagesHistory of Swinng TimelinecharlottevinsmokeNo ratings yet

- Biblical Roots of ConfirmationDocument4 pagesBiblical Roots of Confirmationherbert23No ratings yet

- Anthropology Presentation HandoutDocument40 pagesAnthropology Presentation Handoutapi-437033270No ratings yet

- Truth About Sankofa PDFDocument4 pagesTruth About Sankofa PDFChisomOjiNo ratings yet

- The Nevali Cori Serpent HeadDocument5 pagesThe Nevali Cori Serpent HeadHalli PshdariNo ratings yet

- The Deity of ChristDocument35 pagesThe Deity of ChristLORIE JANE LABORDONo ratings yet

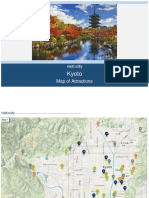

- Kyoto: Map of AttractionsDocument6 pagesKyoto: Map of AttractionsTan Guo HanNo ratings yet

- Ahsanul Qawaaid Workbook Part 3Document45 pagesAhsanul Qawaaid Workbook Part 3MaryamNo ratings yet

- ChödDocument5 pagesChödrangdroll dzogchenrimeNo ratings yet

- Language of Medici 00 Camp U of TDocument348 pagesLanguage of Medici 00 Camp U of TYaniv AlgrablyNo ratings yet

- Khuddi Kya HaiDocument3 pagesKhuddi Kya HaiDr. Momin SohilNo ratings yet

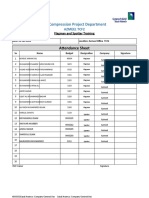

- Hand and Power Tool Training Attendance SheetDocument1 pageHand and Power Tool Training Attendance SheetSheri DiĺlNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19Document33 pagesChapter 19joelleshaulssNo ratings yet

- Bujok Ethnographica PDFDocument16 pagesBujok Ethnographica PDFHenry BregnerNo ratings yet

- MOHSIN BILAL CVDocument1 pageMOHSIN BILAL CVMohsin BilalNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4.2 PDFDocument5 pagesLesson 4.2 PDFMaría Belén TatoNo ratings yet

- Medieval HistoryDocument142 pagesMedieval HistoryVijay Pratap Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- WILLIAMS, Jessica - The Religion of TarotDocument151 pagesWILLIAMS, Jessica - The Religion of TarotFlamboyantChichiNo ratings yet

- 16.01.22 CovishieldDocument2 pages16.01.22 CovishieldHimanshu SethiNo ratings yet

- Basic Magick ClassDocument216 pagesBasic Magick Classloocy44100% (1)

- Redemption SermonDocument8 pagesRedemption SermonbaptistpastorNo ratings yet

- InquisitorDocument242 pagesInquisitorChris HughesNo ratings yet