Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 213.22.63.179 On Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

Uploaded by

Diogo NóbregaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 213.22.63.179 On Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

Uploaded by

Diogo NóbregaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Spirit of the Time: Derrida’s Reading of Hegel in the 1964–65 Lecture Course

Author(s): Peter Gratton

Source: CR: The New Centennial Review , Vol. 15, No. 1, Derrida and French Hegelianism

(Spring 2015), pp. 49-66

Published by: Michigan State University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.14321/crnewcentrevi.15.1.0049

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Michigan State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to CR: The New Centennial Review

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Spirit of the Time

Derrida’s Reading of Hegel in the 1964–65 Lecture Course

Peter Gratton

Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada

If there were a definition of différance, it would be precisely the limit, the inter-

ruption, the destruction of the Hegelian relève [aufgeben] wherever it operates.

What is at stake here is enormous.

—Jacques Derrida, Positions

Pure difference is not absolutely different (from nondifference). Hegel’s critique of

the concept of pure difference is for us here, doubtless, the most uncircumventable

theme. Hegel thought absolute difference, and showed that it can be pure only by

being impure.

—Jacques Derrida, “Violence and Metaphysics”

THE SPECTER THAT HAUNTS ALL OF DERRIDA’S WORK IS THE SPECTER OF

Hegel’s Geist. Derrida considered Hegel as summing up the Western onto-

theological tradition but also as someone whose dialectic would always al-

CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2015, pp. 49–66. ISSN 1532-687X.

© 2015 Michigan State University. All rights reserved.

49

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

50 The Spirit of the Time

ready outflank any full-frontal confrontation with his logic, since any coun-

termove would only be sublated (relève) by the dialectic itself. Like Foucault

and other readers of Hyppolite, Derrida argues that to think Western meta-

physics to its end is to presume that one’s move of opposition or critique

would already be a moment in the Hegelian system, and thus any philosopher

after Hegel must work through the fantasy of absolute systematicity. Taking

up Derrida’s reception of Hegel means considering how one speaks to a ghost

that haunts all of twentieth-century French philosophy after Kojève’s lectures

of the 1930s. And like the ghost that, as Derrida noted in Specters of Marx

(1994), disrupts any coherence to questioning its presence or absence, its

identity or heterogeneity, and so on, the identity of the Hegel whose specter

haunts Derrida’s works is multiple: his earliest writings, including his 1964–65

lecture course, which will be the focus of this essay, target Kojève’s anthropo-

centric version of Hegel, disrupt the sovereignty and partial reading of Ba-

taille’s Hegel, and finally take on the view of Hegelian “whole” informed by his

engagement with Hyppolite, with whom he had an intellectually close profes-

sional relationship in the 1960s. While Bataille and Kojève read Hegel, as did

Sartre and others, through the master-slave dialectic, Derrida joins Hyppolite

in privileging his writings on logic and history, all as part of an overall move

toward the antihumanism for which the sixties generation became known

(Hyppolite 1997, 177–78). But more importantly, Hegel became the lens

through which Derrida understood his own reading of Heidegger—a figure, as

is well known, whose reception in France changed radically not least due to

Derrida’s own writings in the 1960s. While Derrida’s 1964–65 lecture course

Heidegger: la question de l’Être et l’Histoire at the l’ENS-Ulm is largely dedi-

cated to Heidegger, it reveals how indebted “deconstruction,” a term used by

Derrida for the first time in these pages, is to thinking the relation between

Heideggerian “Destruktion” and Hegelian “Aufhebung.”1 In sum, deconstruc-

tion gets under way in Derrida’s thought by thinking the difference between

Hegelian and Heideggerian modes of thought—strikingly reading one in terms of

㛭 “The Ends of

the other throughout these lectures (and in “Ousia and Gramme,”

Man,” and other crucial early works). For Derrida, Hegel is not simply the

ultimate thinker of totalization and homogeneity—as, say, Jean-François Lyo-

tard would depict him in The Postmodern Condition (Lyotard 1984, 33–34)—

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 51

but is also the tradition’s preeminent thinker of difference and relationality.

While of course the difference between difference and identity is sublated

under identity in the Hegelian logic, Derrida recognizes Hegel, as he put in

famously in Of Grammatology, as the last philosopher of the book and the first

thinker of writing. “The horizon of absolute knowledge,” Derrida writes, “is the

effacement of writing in the logos . . . the reappropriation of difference” (Der-

rida 1976, 26). Nevertheless, “all that Hegel thought within this horizon, all that

is except eschatology”—which Derrida’s thinking of finitude must reject for

reasons discussed below, since any eschatology is a determination of the

future from the present—“may be reread as a meditation on writing” (26).

Thus, “Hegel is also the thinker of absolute difference” (26). In what follows, I

proceed in three phases: first, I detail Derrida’s main project in the 1964–65

lecture course, first going through his reading of Heidegger, then describing

how he follows on the heels of Heidegger’s own rendering of Hegel. Second, I

note the ways in which this Hegel becomes the term of art in Derrida’s early

and later writings for onto-theology, and the most thorough one at that. But

last, I move away from this early lecture course to discuss how Derrida dis-

places a certain Heideggerian version of Hegel, one who is too often only a

thinker of totality and presence. In this last section, I discuss how Derrida

reads through Hegel a thinking of time not subsumed under presence, one

that a reading of the Heideggerian type disallows, and that then places Hegel

as the hinge figure between (absolute) metaphysics and its yonder—a thinker,

yes, of totality (the book) but also of difference and dissemination, that is, a

thinker of writing and the trace.

Given at the time in which he was writing Of Grammatology (published in

1967), one can read through the 1964–65 lectures contemporary arguments

over the legacies of the three H’s (Hegel, Husserl, and Heidegger), arguments

that are largely left in the background when Of Grammatology is published two

years later. The deep readings of the three on the meaning of history, the

question of the cloture of Western metaphysics, as well as their mutual inter-

relation are generally left aside and taken for granted in that crucial book, and

before long one is deep in the weeds of Levi-Strauss’s structuralism, Sau-

ssure’s accounts of signification, and Rousseau’s dangerous supplement. Be-

ginning readers thus have to rely on the introduction of Gayatri Spivak in the

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

52 The Spirit of the Time

English edition to paint just some of the background out of which Derrida’s

text is intervening. That Derrida at one point before 1967 considered publish-

ing the course (Janicaud 2001, 96) means perhaps a missed opportunity in the

reception of his work, since what was at stake in Of Grammatology and the

other works of 1967, Voice and Phenomenon and Writing and Difference, was

less the enunciation of a theory of texts, that is, a “literary theory” in the most

reduced sense, than an attempt to tease out central questions relating to

Heidegger’s task of a Destruktion of the history of ontology (with an emphasis

and interrogation of each one of these terms). This history of ontology is first

and foremost represented and offered by Hegel. I’m not denying the impor-

tance of semiology in Derrida’s early writings and teachings, but this part of

his thinking arose by critiquing those moves within structuralism and others

to remove from a given historicity a transcendental signified their works

should otherwise have disallowed, a move in these lectures he identifies also

as the metaphysical attempts of Hegel and Husserl to find an ahistorical

signified beyond temporalization and the structure of the trace (Derrida 2013,

226–27). What he aims to show is that Hegel’s eschatology is a move to a

presence that itself must be absolved from the movement of the dialectic and

historicity. “Every ontology,” Derrida writes, “has implicitly chosen as its guide

such and such a type of being without making its choice a theme or a prob-

lem,” including at times, Hegel’s (Derrida 2013, 123). Derrida’s early reception

in literary theory took up just one thread of a multifaceted trajectory, leaving

to the side his rereadings of classical questions concerning the meaning of

Being and the question of history that are central to his 1960s work (Gratton

2014, 201–15)—and deriving from Heidegger’s project of thinking Being as

time and Hegel’s attempt to think irreducible difference.

Given during his first year as caïman at l’ENS-Ulm beginning November 16,

1964 and ending nine classes later on March 29, 1965, Heidegger: la question de

l’Être et l’Histoire is important for considering the Derridean reception of

Hegel for at least four reasons: 1) Hegel and Heidegger’s writings had been

largely taken up within France—Hyppolite’s focus on the Logos and sense

notwithstanding—in terms of a vague anthropology on loan from selective

readings of the Phenomenology of Spirit and Being and Time, and Derrida’s

lectures look to sever Hegel and Heidegger from the violent readings of Kojève,

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 53

Sartre, and others (Derrida 2013, 283–84). 2) Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit (1927)

suffered from an intermittent and incomplete set of translations since its

publication, which had its own mark on Heidegger’s reception in France.

Derrida’s lectures, during which he translated many German passages him-

self, aimed in part to re-introduce Heidegger to the French academy, reorient-

ing Heidegger studies away from the grips of existentialist renderings (e.g.,

Derrida spends little time on Dasein’s care structure from Division I of Sein

und Zeit) toward Heidegger’s Destruktion of the history of ontology and its

relation to the German Idealism represented by Hegel. Derrida will refuse as

misreadings attempts to create a mélange of Hegel and Heidegger in the

manner of Kojève and Sartre that only manages to repeat the dogmatic meta-

physical gestures critiqued by both Hegel and Heidegger (e.g., Derrida 2013,

139). 3) In light of his Destruktion of the history of ontology, Heidegger’s

reading of Hegel will be—both in the course and for the purposes of this

essay—crucial. It is certainly true that at times Hegel becomes in Derrida the

proper name for metaphysics tout court, and that the mere mention of his

name, say, in proximity to a discussion of Husserl is enough for the reader to

understand that Husserl was implicated in a metaphysics he presumed he had

surpassed (Derrida 2013, 20). This is also a maneuver he reproduces through-

out his career, for example, in aligning Heidegger to a certain Hegelianism,

such as from the very title forward in Of Spirit (1989). Yet we see through the

lectures and other early writings how he shifts crucial ways of receiving

Hegel’s writings on history. 4) Finally, we should note the politics of the ENS in

the mid-sixties. Althusser and his followers were returning to Spinoza to think

a Marxism unallied to the “power of the negative” found in the supposed

Hegelianism of Marx’s early writings—this matching a supposed “anti-

Hegelianism,” however ambiguous, of much 1960s French philosophy. In

striking passages, while not mentioning Althusser, Derrida argues that to

understand Marx’s work on labor, for example, one must return and reread

Hegel critically on precisely these points—not dismiss him (Derrida 2013,

286–88). Derrida’s long engagements with Hegel—he is either the subject of or

cited heavily in just about every essay Derrida published in the 1960s—show

the import of Hegelian negativity for deconstruction, however much that

went against a certain spirit of the time.

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 101 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

54 The Spirit of the Time

On the other hand, Derrida sets out to displace—one can think of Sartre’s

later work here in the Critique of Dialectic Reason—those who took Hegelian

totalization as providing a concrete telos to history the left should be looking

for. Against these supposed radical political programs, Derrida’s course

makes clear his view that the most radical dis-assembling of the history of

ontology and the latter-day politics to which it gave rise springs not from

reinvigorating a moribund Marxism or to dismiss dialectic and difference in

toto to interpolate class apparatuses. For Derrida, all the key terms thrown

around in that era, from “materialism” to “structure” to “metaphysics” to

“history” to “totalization” and so on, are to be rethought by way of a long

engagement and deconstruction of the Heideggerian Hegel (and vice versa).

Of course, much of the lectures are given over to step-by-step analyses of

Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit, as well as ancillary writings up to the time in which

Derrida was lecturing. Derrida’s approach is to concentrate on those passages

in Heidegger that call for a rethinking of history and for reopening the ques-

tion of being—along with those passages that portend the foreclosure of a

once-promised third division. His reading of Heidegger is, for the most part,

sympathetic, and all of his important later readings of Heidegger, such as in

㛭 Of Spirit, and Aporias, among numerous other places,

“Ousia and Gramme,”

are set up here. Yet the text begins with a consideration of what “refutation”

means in light of taking up the legacy of a given thinker, especially as it

pertains to the writings of Hegel, given the work of Aufheben, which neither

refutes nor simply abandons any term or idea. That is, he is thinking of

Heidegger’s relation to the metaphysics represented by Hegel, noting that

neither simply affirming nor abandoning a term, as in Hegel, is of absolute

proximity to the Destruktion of the history of ontology in Heidegger’s work,

which must take on, in both senses of the phrase, a given conceptual legacy—

neither refuting metaphysics nor simply standing in opposition to it. For

Derrida, it is Hegel who sets up Heidegger’s discussions of the end of the West

and so on: “The philosophy of Hegel as last philosophy has been the philoso-

phy that has thought in itself the essence of the last philosophy in general, of

what the last would mean in philosophy” (Derrida 2013, 28), which is why

Hegel is invoked, Derrida argues, from the very first paragraph of Heidegger’s

magnum opus to its last pages. And it is why Hegel himself cannot be sublated

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 55

toward a “beyond” of metaphysics, to another last figure, not least since for

Derrida Hegel is the thinker of history and thus what any “beyond” would

mean. Rather Heidegger must, as the preface to Being and Time makes clear,

maintain a movement that neither strictly repeats Hegelianism nor leaves it

unscathed, producing a “trembling” that “says nothing else after the Hegelian,

that is to say, Occidental ontology that it is going to destroy. . . . [Heidegger]

does not propose another ontology, another theme, another metaphysics”—

here we read Derrida’s scathing criticisms of a whole generation of writing on

Heidegger, in France and beyond—“Heideggerian destruction is neither a

criticism of an error nor simply the negative exclusion of the past of philoso-

phy. It’s a destruction, that is to say, a deconstruction [c’est-à-dire, une décon-

struction], that is to say, de-structuration . . . in order to bring forth [Occiden-

tal ontology’s] structures, strata, and its system of sedimentation” (Derrida

2013, 34). Here in his first recorded use of this now historic term, Derrida links

“deconstruction” to a consideration of the “nothing” that Heidegger adds to

Hegel, arguing that it’s in the “difference between” the two that the questions

of the seminar take shape (30). For Derrida, Heidegger, while saying nothing

other than Hegel, will nevertheless have produced a “radical affirmation of an

essential link between being and history” (30). Of course, history as such was

never better formulated than in Hegel’s lectures on the topic, and no one

would deny that the epochality of Heidegger’s own history of ontology owes

much to Hegel’s own historicization (and eschatology) of philosophical

method. But Derrida will argue in the lectures that Hegel, like Husserl after

him, attempts to think absolute historicity while himself forcing a pivot out of

the stream of history to an eternal stance—a classical metaphysical move:

Ontology has always been constituted by a gesture of extraction [arrachement] from

historicity and from temporality, even for Hegel for whom the history of the manifes-

tation of an absolute and eternal concept, of a divine subjectivity which, in its origin

and in its end, appears to totalize infinitely its historicity, that is to say, live in the total

presence of being with itself, that is to say, in non-historicity. (Derrida 2013, 50)

Where Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit teases out the relation between Being and

history, Hegel’s mediation of both in terms of the concept means that he

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

56 The Spirit of the Time

“ultimately reduces the thought of being to the concept of being” and his

Idealism “determines the whole of being as free subjectivity (founded on

Cartesianism) and the volition of volition [volonté de la volonté]” (Derrida

2013, 47). For Heidegger, despite all manner of complications, these both

follow from Hegel’s elucidation of time as the “negation of the negation” in

Philosophy of Nature, part 2 of the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences

(Hegel 2004, 34), as well as his view that “Hegel’s conception of time presents

the most radical way in which the ordinary understanding of time has been

given form conceptually,” and this thinking of time informs both his and

Derrida’s readings (Heidegger 1962, 482).

In § 82 of Sein und Zeit, Heidegger sets out to demonstrate that Hegel’s

view of time follows from the “vulgar” view on loan from a tradition dating at

least to Aristotle. But also true to Aristotle’s treatment of time, found in the

Physics, Hegel’s analysis of time has its focus in the philosophy of nature, a

crucial error, for Heidegger, since it will mean that Hegel cannot think of time

in terms of the ecstatic structure of Dasein, that is to say, he can only think

time in terms of the now points that have given us the ticktock of the not-so-

modern clock. The “negation of negation” of Hegel’s time means nothing

other than a “punctuality,” a spatialization of time in terms of a chain of

externally related “nows” that are “present to hand” (Heidegger 1962, 432). Put

more simply, the negation is the spatialization or separatedness of each now,

and the negation of the latter negation is the ordering of those now in a given

line. Hegel’s view of time would be precisely an abstraction—perhaps a repe-

tition of the very first abstraction that allowed concepts, as it were, to move

outside of time in the theoretical glance—from the ecstases of past and future

of the being-in-the-world of Dasein. Hegel writes: “Time, as the negative unity

of self-externality, is similarly an out-and-out abstract, ideal being. It is that

being which, inasmuch as it is, is not, and inasmuch as it is not, is; it is purely

Becoming intuited [das angeschaute Werden]” (Hegel 2004, 34). But as purely

intuited, as the nonsensuous sensuous, “in its Notion, time itself is eter-

nal . . . absolute Presence . . . The Idea, spirit transcends time because it is

itself the Notion of time; it is eternal, in and for itself, and it is not dragged into

the time process because it does not lose itself in one side of the process” (37).

In this way, Hegel will, on Heidegger’s view, depict Spirit as “falling into time”

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 57

(Heidegger 1962, 428), therefore understanding Spirit as having an external

relation to time, even as that relation is said to be the relation of Spirit to itself.

Spirit becomes concrete and enters into the finite world only as it becomes

revealed as a process in time, which in turn is understood only in terms of a

“world-time” leveled-out and fallen from the temporality of Dasein’s being-in-

the-world. For Heidegger, Spirit does not fall into time and thus provide for

the concreteness of Dasein’s factical existence. Rather, Dasein itself is what

falls from primordiality into the public time that Hegel in turn reifies into the

time of nature in the second volume of the Encyclopaedia.

At key points in the 1964–65 lecture course, Derrida appears to repeat this

reading of Hegel, especially Heidegger’s view that Hegelianism is but a Carte-

sianism writ large. Heidegger is thus guilty of isolating but one moment in a

system that is itself an aufheben of another opposition, in some sense reifying

and abstracting a moment that is part of a developmental system—a reading

as one-sided as those that think all human relations in Hegel through the

master-slave dialectic. In short if we abstract one moment—however abstract

it calls itself, as Hegel does about time—we play into the (re)presentational

logic Heidegger is calling into question in the first place. “Metaphysics,” Der-

rida writes, “determines the world as an object and therefore as available

[disponible] for an action and a conception” (Derrida 2013, 200). In the lecture

course, Derrida leaves open whether there is a Hegel beyond the “literal and

conventional” (59), one who is not just the thinker of the nonhistorical becom-

ing of the Spirit to itself as absolute knowing and substance, of pure presence,

that is, the God of Hegel’s History lectures. In this way, Derrida will critique, as

he does Michel Henry (271), Husserl (among many places, 193), and at points

Heidegger as producing “Hegelian conclusions,” despite their supposed criti-

cisms, when they recommence his thinking of the self-present auto-affection

of the being for itself (268). This Hegelianism is nothing other than a synonym

for the metaphysics of presence, based on the supposition of a time beyond

time, of the ever presence of an eternity of which the passing “now” is but a

shadow. This thinking of presence allows Hegel to think the absolute avail-

ability of being since the past is always approachable only from the present—

and so too the future. Against this, Derrida’s whole thinking of the trace is

precisely of a past that can never be made present (Derrida 1982a, 21). Yet for

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

58 The Spirit of the Time

Hegel, “there is only historicity inasmuch as the past and the origin can be

rendered present . . . Presence would be therefore the condition of historicity

and its form” (Derrida 2013, 211). This metaphysics of presence would be part

of a desire for seizing all, of all being available to Spirit, even its death. But,

“the certitude of the living present, as the absolute form of experience and

absolute source of meaning [sens], presupposes as such the neutralization

of my birth and my death. . . . The Present is by essence what could never

end. It is in-itself ahistorical” (214). Thus absolute knowing, as the telos of

Hegelian thought, would be a totalization that is less spatial than tempo-

ral—that is, an all-at-once in the eternal moment of absolute availability of

one and all, beyond or before all death, thus obliterating death in the first

and last moment of philosophy (224). “In spite of the immense Hegelian

revolution,” Derrida writes, “to think of death within the horizon of the

infinite and presence [la parousie] in an absolute fashion, which is pure

life” is a work that “sublimates death” (292).

What one could oppose to the presence of the now in time would be a

thinking based on its temporal modification, the eternal presence outside of

time of ahistoricity—a move familiar since Plato, which uses the inherent

contradictions of positing the now to oppose it to the eternity of pure presence

beyond time. But is there another course? What could one oppose to this false

option given by the metaphysics of presence, if the evidence of evidence, its

temporal mode, has always been a presence-to? What needs to be countered

to this self-evident temporal form, again this “evidence of evidence,” is not

“another form of evidence,” which could only be metaphysical, Derrida ar-

gues, but “historicity itself” (2013, 213). But this historicity would not be a

“becoming” (145), which itself would be a form of temporalization, suggesting

a continuity—say, in the form of a line—that can always be represented and is,

of course, the central moment in the Hegelian dialectic, since it is the very

form of movement from being to nothingness, from one thing to another. For

Derrida, one would have to think a historicity that would involve a past that

could not be made present—and also a future beyond the future present. Such

is the consideration of the trace structure of Derrida’s work from these lec-

tures to his last writings.

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 59

Since the trace is not a presence but the simulacrum of a presence that

dislocates itself, displaces itself, refers itself, it properly has no site—erasure

belongs to its structure [emphasis mine; we will see how Derrida reads this

through Hegel in a moment]. And only the erasure which must always able to

overtake it (without which it would not be a trace but an indestructible and

monumental substance), but also the erasure which constitutes it from the

outset as a trace. . . . The paradox of such a structure, in the language of

metaphysics, is an inversion of metaphysical concepts, which produces the

following effect: the present becomes the sign of the sign, the trace of the trace.

(Derrida 1982a, 24)

In almost a “somnambulant style,” one could, Derrida warns, repeat a

“powerless” and “juvenile” style of aggression found too often with regard to

metaphysics and transcendental phenomenology. But this move, in which

one considers one’s “privilege” that one is in a Western epoch that is closing in

on itself and opening onto something else, is precisely “the Hegelian moment”

and gesture (Derrida 2013, 228). This would be Derrida’s critique of all consid-

erations of postmodernity, whose very name suggests one can posit oneself as

both within a given epoch (the modern, the metaphysical, and so on) and

erase that very historicity to think some beyond glimmering over the horizon

(231).

Soliciting Hegel would not seek merely to move aside his work and all that

it represents but would pay attention to those moments where Hegel unworks

the very systematicity for which he is the proper name—where his famed

“presuppositionless” is taken to its end to unground any metaphysical foun-

dation. To put it another way, to allow Hegel to be the last metaphysical

thinker, to assume his absolute systematicity that one is critiquing, is to give a

certain Hegel the final victory, a point, for example, that underlies Derrida’s

reading of Hegel’s early writings on Christianity and the family in Glas (1973).

One then merely represents oneself as an opponent that is outside a “whole”

that would be Hegelian thought, reifying what was supposed to be in conten-

tion, and thus one would make of Hegel merely a repeater of what has been

vulgar throughout the West, specifically its concept of time (Derrida 2013,

317–19). Beyond this vulgar Hegel is a reading of the Derridean type, one that,

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

60 The Spirit of the Time

for example, Jean-Luc Nancy, who studied Hegel with Derrida, would find in

The Restlessness of the Negative while attuned to Hegel’s “infinite negativity of

the present,” and Catherine Malabou (1996), another student of Derrida, finds

in his notion of plasticity (Nancy 2002, 9).

It is precisely the question of vulgarity that Derrida takes up in “Ousia and

㛭 based, it’s clear, in large part on the lectures discussed above.

Gramme,”

Published first in 1968 and collected in Margins of Philosophy, Derrida’s essay

concentrates on the longest footnote in Sein und Zeit, from § 82, where

Heidegger encircles Hegel within a thinking of time going back to Aristotle.

㛭 is given over to a complex reading of Aristotle’s

Much of “Ousia and Gramme”

Physics (IV 10–14), as Derrida questions the distinction made by Heidegger

between a “vulgar” concept of time and a primordial temporality from which

it has fallen. In the vulgar concept of time, time comes as a repetition of nows as

Dasein is lost in its very concerns, in the “They” of everydayness. As he notes both

㛭 there can be no concept of the fall

in the lecture course and “Ousia and Gramme,”

outside an “ethico-theological orb” (Derrida 1982b, 45), but more to the point,

Derrida argues that any “concept of time belongs in all its aspects to meta-

physics [since] it names the domination of presence” (63), and for similar

reasons he will argue that he will not provide another ontology in the 1964–65

course but rather extend its deconstruction (Derrida 2013, 1–3). The target of

Derrida’s reading is less concerned with Heidegger’s reading of Aristotle than

Heidegger’s reading of Hegel, whom Heidegger had said merely repeated and

“paraphrased” Aristotle’s vulgarism of time—thus opening Heidegger up for a

critique of his notion of primordial time as well as what it means to read Hegel

differentially. Citing key passages from Hegel in the longest footnotes in “Ousia

㛭 Derrida notes that one can both “confirm” and “challenge” the

and Gramme,”

interpretation of Hegel in Sein und Zeit.

Derrida writes that Heidegger’s reading is based only on Hegel’s philoso-

phy of nature, as if that view of time could pass “unchanged into a ‘philosophy

of spirit’ or into a ‘philosophy of history’” (1982b, 46 n. 22). As Derrida notes—

in passages, admittedly, as opaque as any in his early writings, though filled in

now by relevant discussions in the lecture course—one can only do so by way

of a vulgar reading of Hegel himself: “time is also this passage” from nature to

history or spirit, since “time” is the “first relation of nature itself, the first

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 61

emergence of its for-itself, spirit relating itself to itself” (43), that is, time is the

self-externalization, on Hegel’s account, of any thing (say nature) from itself.

What Heidegger writes about Hegel’s view of time is “of limited pertinence due

to the relevant (cf. aufheben) structure of the relations between nature and

non-nature in speculative dialectics” (43). There is no simple nature and

therefore “time” (of nature) in Hegel, since “nature is outside spirit itself, as the

position of its proper being-outside itself” (43). Moreover, as the index of

exteriority as such, “at each stage of the negation, each time that the Aufhe-

bung produced the truth of the previous determination, time was requisite”

(42), even if Hegel were given, as he does in the Philosophy of Nature, to equate

the natural with time and the spiritual with the eternal in a Platonist trope

(Hegel 2004, 35). One cannot think, then, dialectics without the differential

structure of time and the trace.

Let me cite where Derrida both moves near and far from Heidegger’s

㛭

reading of Hegel in “Ousia and Gramme”:

Hegel calls the telos that puts movement in motion, and that orients becoming

toward itself, the absolute concept or subject. The transformation of parousia

in self-presence, and the transformation of the supreme being into a subject

thinking itself, does not interrupt the fundamental tradition of Aristotelian-

ism. The concept as absolute subjectivity itself thinks itself, is for itself and

near itself, has no exterior, and it assembles, erasing them, its time and its

difference in self-presence. (Derrida 1982b, 52)

In this way, Derrida writes in a footnote attached to the above, “if time has

a meaning in general, it is difficult to see how it could be extracted from

onto-theo-teleology” as in Hegel (53 n. 32). Because time means ultimately,

in metaphysics, its erasure, it “has been suppressed at the moment one

asks the question of its meaning, when one relates it to appearing, truth,

presence, or essence in general” (52, n. 32). If the meaning of time is its

presence outside of time—here, we can think in everyday terms of its

reducibility to a repeatable, eternal form: circle, line, point—then time is

only realized in its self-erasure; it can only be thought, that is brought

within the concept, as a “negative unity of self-externality.” As Hegel

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

62 The Spirit of the Time

writes, “It is that being which, inasmuch as it is, is not, and inasmuch as it

is not, is,” a “nonsensuous sensuousness,” and “empty intuition,” and so on

(Hegel 2004, 34). As Derrida rightly puts it, “The question asked at this

moment is that of time’s realization,” that is, time’s reality (or coming to

reality) outside a given concept, which can only be thought within a Hegelian

milieu, however, in which “being outside oneself,” for example, has any mean-

ing. Derrida continues: “Perhaps this is why there is no other possible answer

to the question or the meaning of Being of time [which had been, recall, the

entire project of Heidegger’s followed in Derrida’s 1964–65 lecture course]

than the one given at the end of the Phenomenology of Spirit: time is that which

erases [tilgt] time” (Derrida 1982b, 53 n. 32). This erasure, though, is also a

“writing which gives time to be read, and maintains it in suppressing it” (53 n.

32). But by erasing time while writing it, the dialectic then, like the writing of

㛭 all the theology and

the trace in Derrida’s works, upsets any telos or arche,

teleology and all that a certain Hegel would be said to represent, even if, in the

end, time, differentiation, and the becoming-space of externalization that is

negativity itself could no longer be represented. Ultimately this marks a cru-

cial place of incursion by Derrida into Hyppolite’s rendering of Hegel. Recall

that for Hyppolite, Hegel’s key move is to render the absolute sensible—as

opposed, say, to Schelling’s prius, which must always be before intelligibility—

and also to claim that language is the very space of the Logos. This is a point

that Derrida makes central in the 1964–65 lectures, noting that both in Hegel

and Heidegger the coming to language of sense, of meaning, is the very place of

historicity, a point made by Hyppolite as well, and he weds Heidegger’s ac-

count of the “house of being” to Hegel’s account of the logos (Derrida 2013,

86–88), even if Heidegger himself reduces Hegel’s dialectic to a question of

presence to consciousness (222–23). Hyppolite writes:

The dialectical demonstration is intimately united to the reality that inter-

prets itself and reflects itself in meaningful language . . . Actuality understand-

ing itself and expressing itself as human language is what Hegel calls the

concept or sense already immanent to the being of absolute knowl-

edge. . . . Human language, the Logos, is this reflection of being into itself

which always leads back to being, which always closes back on itself indefi-

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 63

nitely, without ever positing or postulating a transcendence distinct from this

internal [read: to the system, not to an individual subject] reflection. (Hyppo-

lite 1997, 4)

In sum, then, “human language” is the “very medium of the dialectic”

(6), or as Derrida puts in his own reading of Hegel and Heidegger, “there is

no historicity without language” (Derrida 2013, 83). Hyppolite’s formula-

tion, of course, would be crucial to structuralism and poststructuralism to

follow, since historical instantiations of spirit and the sense of being are

productive of given forms of specific individual consciousnesses—against,

say, the voluntarist conceptions of Sartre—or rather, there is no language

without sense and vice versa (Hyppolite 1997, 21). Derrida’s intervention, at

this point, is to ask after the question of language and the privileging of the

presence of the speaking subject that is the linguistic analog of the privileging

of temporal presence, as Heidegger reads Hegel (Derrida 2013, 247, 320). If

language, as Derrida argues, is presuppositionless—without an outside guar-

antor, or transcendental signified—then one should wed this account to the

presuppositionlessness of Hegel’s dialectic, no longer present to an “outside”

of a given subject or eternal being. In this way, the dialectic becomes, as with

Saussurean semiology, a thinking of difference that is always related nega-

tively to every other moment of the system, a groundless ground trembling at

its nonexit from metaphysics, while testifying to its very limit. This means not

inventing, as Derrida makes clear in the 1964–65 lecture course and in “Ousia

㛭 another thinking of time, since “time” itself, as Hegel demon-

and Gramme,”

strates, only has a meaning “within” its self-differentiation from the trace of

metaphysical determinants that give it sense in the first place. Here we can

link, then, the erasure of time in the writing of Hegel to what Derrida describes

above as the writing and erasure of the trace: the absolute is the presence/

absence of the becoming-space of time (and vice versa), where writing is what

Jean-Luc Nancy calls excription (Nancy 2008, 17–19), a becoming and writing

of sense in the Derridean meaning of écriture not present to a given being (e.g.,

the human) and not precisely present in the temporal sense either. This is not

a “phantom of the ineffable,” as Hyppolite puts it, but the nonpresent logic of

différance tracing itself out in the thought of Derrida and Hegel. In this way, no

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

64 The Spirit of the Time

system, even Hegel’s, can be presented “all-at-once,” here and now, and thus

available present to hand, as Heidegger wished to do. Thus it awaits its

invention and future beyond the Hegelian holisms of the oft-cited caricature.

NOTES

1. In his translation of Heidegger’s Destruktion, Derrida notes in the lectures his preference for

solliciter to translate this notion, derived from the Latin solus (whole) and ciere (to move) to

mean to make an entire thing tremble, as in the Western tradition read through his work.

See Derrida (1982a, 21; and 2013, 209).

REFERENCES

Derrida, J. 1973. Glas, trans. J. P. Leavey and R. Rand. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,

1990.

. 1976. Of Grammatology, trans. G. Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

. 1978. Violence and Metaphysics: An Essay on the Thought of Emmanuel Levinas. In

Writing and Difference, 79–153. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

. 1981. Positions, trans. A. Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

. 1982a. Différance. In Margins of Philosophy, trans. A. Bass, 1–28. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

㛭

. 1982b. Ousia and Gramme. In Margins of Philosophy, trans. A. Bass, 29–68. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

. 1982c. The Ends of Man. In Margins of Philosophy, trans. A. Bass, 109–36. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

. 1989. Of Spirit: Heidegger and the Question, trans. G. Bennington and R. Bowlby.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

. 1994. Specters of Marx: The State of Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New

International, trans. P. Kamuf. New York: Routledge.

. 2013. Heidegger: la question de l’Être et l’Histoire: Cours de l’ENS-Ulm 1964–1965, ed. T.

Dutoit. Paris: Galilée.

Gratton, Peter. 2014. Speculative Realism: Problems and Prospects. London: Bloomsbury.

Hegel, G. W. F. 2004. Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences. Part 2, Philosophy of Nature,

trans. A. V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. 1962. Being and Time, trans. J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson. San Francisco:

Harper Collins.

Hyppolite, J. 1997. Logic and Existence, trans. L. Lawlor and A. Sen. Albany: State University of

New York Press.

Janicaud, D. 2001. Heidegger en France. Paris: A. Michel.

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Gratton 65

Lyotard, J.-F. 1984. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. G. Bennington.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Malabou, C. 1996. L’avenir de Hegel: plasticité, temporalité, dialectique. Paris: J. Vrin.

Nancy, J.-L. 2002. Hegel: The Restlessness of the Negative, trans. J. E. Smith and S. Miller.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

. 2008. Corpus, trans. R. Rand. New York: Fordham University Press.

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

66

This content downloaded from

213.22.63.179 on Thu, 28 Apr 2022 15:03:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- From Life to Survival: Derrida, Freud, and the Future of DeconstructionFrom EverandFrom Life to Survival: Derrida, Freud, and the Future of DeconstructionNo ratings yet

- Legacies of DerridaDocument37 pagesLegacies of DerridaR_TeresaNo ratings yet

- Way Dasenbrock. Reading Derrida's ResponsesDocument20 pagesWay Dasenbrock. Reading Derrida's ResponsesjuanevaristoNo ratings yet

- Martin Hägglund's Radical Atheism - Derrida and The Time of LifeDocument9 pagesMartin Hägglund's Radical Atheism - Derrida and The Time of LifeeduvigeslaercioNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews / TH e International Journal of The Platonic Tradition 2 (2008) 206-232Document5 pagesBook Reviews / TH e International Journal of The Platonic Tradition 2 (2008) 206-232Cidadaun AnônimoNo ratings yet

- Miriam Leonard Ed Derrida and AntiquityDocument3 pagesMiriam Leonard Ed Derrida and AntiquityDracostinarumNo ratings yet

- Plebuch DamianDocument272 pagesPlebuch DamianwizsandNo ratings yet

- Paradigma Shift in HeideggerDocument24 pagesParadigma Shift in Heideggerneo-kerataNo ratings yet

- Heidegger BoredomDocument20 pagesHeidegger Boredomskantzos100% (2)

- Heideggers ReticenceDocument33 pagesHeideggers ReticenceАнтон СвердликовNo ratings yet

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Human StudiesDocument19 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Human StudiesCinthia MendonçaNo ratings yet

- Johnson - Derrida and ScienceDocument18 pagesJohnson - Derrida and ScienceMaureen RussellNo ratings yet

- Toby Houston Toole - The Ways of Reflection - Heidegger, Science, Reflection, and Critical InterdisciplinarityDocument67 pagesToby Houston Toole - The Ways of Reflection - Heidegger, Science, Reflection, and Critical Interdisciplinarity3x4 ArchitectureNo ratings yet

- Jacques Derrida: ObjectivesDocument10 pagesJacques Derrida: ObjectivesMarijoy GupaalNo ratings yet

- Rigor by BenningtonDocument20 pagesRigor by BenningtonRousseauNo ratings yet

- Project Muse 820379Document27 pagesProject Muse 820379zshuNo ratings yet

- Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction PDFDocument10 pagesJacques Derrida and Deconstruction PDFZeeshanAliNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics in DeconstructionDocument19 pagesAesthetics in DeconstructionChema NubeNo ratings yet

- Martin Heidegger Research PaperDocument7 pagesMartin Heidegger Research Paperjpccwecnd100% (1)

- Derrida and The End of The World Author(s) : Sean Gaston Source: New Literary History, SUMMER 2011, Vol. 42, No. 3 (SUMMER 2011), Pp. 499-517 Published By: The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument20 pagesDerrida and The End of The World Author(s) : Sean Gaston Source: New Literary History, SUMMER 2011, Vol. 42, No. 3 (SUMMER 2011), Pp. 499-517 Published By: The Johns Hopkins University PressEvan JackNo ratings yet

- Tragedy, Dialectics, and Differancee On Hegel and Derrfda': Karin de BoerDocument27 pagesTragedy, Dialectics, and Differancee On Hegel and Derrfda': Karin de Boerjimmy esteban moreno rojasNo ratings yet

- Martin Heidegger Key Concepts ReviewDocument4 pagesMartin Heidegger Key Concepts Reviewbeynam6585No ratings yet

- A Companion To Heidegger S Introduction PDFDocument7 pagesA Companion To Heidegger S Introduction PDFNathan Jahan100% (1)

- Rip Article p1 - 1Document32 pagesRip Article p1 - 1Andrei GabrielNo ratings yet

- Socratic Ironies Reading Hadot Reading KierkegaardDocument27 pagesSocratic Ironies Reading Hadot Reading KierkegaardJoel MatthNo ratings yet

- Frege and Heidegger on the InexpressibleDocument25 pagesFrege and Heidegger on the InexpressibleQilin Yang100% (1)

- Heidegger and Deleuze: The Groundwork of Evental OntologyFrom EverandHeidegger and Deleuze: The Groundwork of Evental OntologyNo ratings yet

- HeideggerDocument22 pagesHeideggerJuvenal Arancibia DíazNo ratings yet

- Deconstructive Method ExplainedDocument10 pagesDeconstructive Method ExplainedIbadur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Improbable Encounter: Gadamer and Derrida: IntertextDocument5 pagesImprobable Encounter: Gadamer and Derrida: IntertextPeter El RojoNo ratings yet

- The Odd Couple Heidegger and DerridaDocument36 pagesThe Odd Couple Heidegger and DerridaSanti MondejarNo ratings yet

- Bernasconi - Heidegger's Destruction of PhronesisDocument21 pagesBernasconi - Heidegger's Destruction of PhronesisAngelnecesarioNo ratings yet

- Heidegger S Question of Being Dasein Truth and History PDFDocument253 pagesHeidegger S Question of Being Dasein Truth and History PDFRubén García Sánchez100% (2)

- A Philosophical AnalysisDocument20 pagesA Philosophical AnalysisjuckballeNo ratings yet

- (Christopher Norris Vol 2 n1 1988) Christopher Norris-Deconstruction, Postmodernism and Philosophy of Science - Epistemo-Critical Bearings (1988)Document33 pages(Christopher Norris Vol 2 n1 1988) Christopher Norris-Deconstruction, Postmodernism and Philosophy of Science - Epistemo-Critical Bearings (1988)DanishHamidNo ratings yet

- (18725473 - The International Journal of The Platonic Tradition) Heidegger and Aristotle - The Twofoldness of BeingDocument5 pages(18725473 - The International Journal of The Platonic Tradition) Heidegger and Aristotle - The Twofoldness of BeingCidadaun AnônimoNo ratings yet

- A Brief Description of Jacques Derrida's Deconstruction andDocument7 pagesA Brief Description of Jacques Derrida's Deconstruction andMilica SekulovicNo ratings yet

- Kremer-Martin Heidegger's Influence On Richard Rorty's PhilosophyDocument16 pagesKremer-Martin Heidegger's Influence On Richard Rorty's PhilosophyAlexander KremerNo ratings yet

- Late Derrida Sovereignty PDFDocument19 pagesLate Derrida Sovereignty PDFjuanevaristoNo ratings yet

- Heidegger - SymposiumDocument31 pagesHeidegger - SymposiumCorey Wayne LandeNo ratings yet

- Review of Heidegger and HomecomingDocument5 pagesReview of Heidegger and HomecomingrmancillNo ratings yet

- (Greg Shirley) Heidegger and Logic The Place of LDocument186 pages(Greg Shirley) Heidegger and Logic The Place of LGabriela DeptulskiNo ratings yet

- Heidegger's Concept of Temporality Reflections of A Recent CriticismDocument22 pagesHeidegger's Concept of Temporality Reflections of A Recent Criticismaseman1389No ratings yet

- Heidegger and RhetoricDocument202 pagesHeidegger and RhetoricMagda AliNo ratings yet

- CH023 Kates RoutledgeDocument16 pagesCH023 Kates RoutledgegotkesNo ratings yet

- Jacques Derrida - of SpiritDocument19 pagesJacques Derrida - of SpiritsanchezmeladoNo ratings yet

- Heidegger Kritik—Poetic Approach to TechnologyDocument80 pagesHeidegger Kritik—Poetic Approach to TechnologyCrobin 20No ratings yet

- Deconstruction - Nancy J. HollandDocument11 pagesDeconstruction - Nancy J. HollandtomavinkovicNo ratings yet

- Politics of Deconstruction: A New Introduction to Jacques DerridaFrom EverandPolitics of Deconstruction: A New Introduction to Jacques DerridaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Senatore, Mauro - Phenomenology and DeconstructionDocument8 pagesSenatore, Mauro - Phenomenology and DeconstructionTajana KosorNo ratings yet

- DaseinDocument4 pagesDaseincabezadura2No ratings yet

- Beyond Heidegger: From Ontology To Action: Andrew CooperDocument16 pagesBeyond Heidegger: From Ontology To Action: Andrew CooperenanodumbiNo ratings yet

- Timothy Clark, Heidegger, Derrida, and The Greek Limits of PhilosophyDocument18 pagesTimothy Clark, Heidegger, Derrida, and The Greek Limits of PhilosophygonzorecNo ratings yet

- HeideggerDocument21 pagesHeideggerThomas Scott JonesNo ratings yet

- Simon Gendinning Derrida A Very Short Introduction PDFDocument3 pagesSimon Gendinning Derrida A Very Short Introduction PDFJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- Prophets of Extremity: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, DerridaFrom EverandProphets of Extremity: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, DerridaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- (Supplements To Vigiliae Christianae 1) Tertullian - de Idololatria - Critical Text, Translation and Commentary-BrillDocument165 pages(Supplements To Vigiliae Christianae 1) Tertullian - de Idololatria - Critical Text, Translation and Commentary-BrillDiogo NóbregaNo ratings yet

- (Pauline and Patristic Scholars in Debate 1) Todd D. Still - Tertullian and Paul-T&T Clark (2013)Document347 pages(Pauline and Patristic Scholars in Debate 1) Todd D. Still - Tertullian and Paul-T&T Clark (2013)Diogo NóbregaNo ratings yet

- Tertullian - Ernest Evans (Ed.) - Tertullian's Treatise On The Incarnation - Q. Septimi Florentis Tertulliani de Carne Christi Liber (1956)Document120 pagesTertullian - Ernest Evans (Ed.) - Tertullian's Treatise On The Incarnation - Q. Septimi Florentis Tertulliani de Carne Christi Liber (1956)Diogo Nóbrega100% (1)

- G. W. Bowersock - Martyrdom and Rome (Wiles Lectures) - Cambridge University Press (1995)Document118 pagesG. W. Bowersock - Martyrdom and Rome (Wiles Lectures) - Cambridge University Press (1995)Diogo NóbregaNo ratings yet

- Group Assgnmt 8 Rev080515Document9 pagesGroup Assgnmt 8 Rev080515Suhaila NamakuNo ratings yet

- Communication Strategy Target AudienceDocument47 pagesCommunication Strategy Target Audienceguille simariNo ratings yet

- Unilever BD Recruitment and Selection ProcessDocument34 pagesUnilever BD Recruitment and Selection Processacidreign100% (1)

- School RulesDocument2 pagesSchool RulesAI HUEYNo ratings yet

- 1967 Painting Israeli VallejoDocument1 page1967 Painting Israeli VallejoMiloš CiniburkNo ratings yet

- Beaba Babycook Recipe BookDocument10 pagesBeaba Babycook Recipe BookFlorina Ciorba50% (2)

- NASA: 181330main Jun29colorDocument8 pagesNASA: 181330main Jun29colorNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- Major Discoveries in Science HistoryDocument7 pagesMajor Discoveries in Science HistoryRoland AbelaNo ratings yet

- Italy, Through A Gothic GlassDocument26 pagesItaly, Through A Gothic GlassPino Blasone100% (1)

- IFCRecruitment Manual 2009Document52 pagesIFCRecruitment Manual 2009Oklahoma100% (3)

- Moldavian DressDocument16 pagesMoldavian DressAnastasia GavrilitaNo ratings yet

- Reported SpeechDocument2 pagesReported SpeechlacasabaNo ratings yet

- The Merchant of Venice QuestionsDocument9 pagesThe Merchant of Venice QuestionsHaranath Babu50% (4)

- Foreign AidDocument4 pagesForeign AidJesse JhangraNo ratings yet

- Afro Asian LiteratureDocument62 pagesAfro Asian LiteratureNicsyumulNo ratings yet

- Hacking Web ApplicationsDocument5 pagesHacking Web ApplicationsDeandryn RussellNo ratings yet

- Royal Scythians and the Slave Trade in HerodotusDocument19 pagesRoyal Scythians and the Slave Trade in HerodotusSinan SakicNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Manufacturing ProcessesDocument64 pagesIntroduction To Manufacturing Processesnauman khanNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Flexible Learning EnvironmentDocument2 pagesModule 4 Flexible Learning EnvironmentRyan Contratista GimarinoNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual 06 CSE 314 Sequence and Communication DiagramDocument6 pagesLab Manual 06 CSE 314 Sequence and Communication DiagramMufizul islam NirobNo ratings yet

- First Communion Liturgy: Bread Broken and SharedDocument11 pagesFirst Communion Liturgy: Bread Broken and SharedRomayne Brillantes100% (1)

- Og FMTDocument5 pagesOg FMTbgkinzaNo ratings yet

- MarketNexus Editor: Teri Buhl Character LetterDocument2 pagesMarketNexus Editor: Teri Buhl Character LetterTeri BuhlNo ratings yet

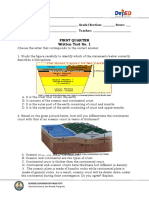

- Written Work 1 Q1 Science 10Document6 pagesWritten Work 1 Q1 Science 10JOEL MONTERDENo ratings yet

- Teresita Dio Versus STDocument2 pagesTeresita Dio Versus STmwaike100% (1)

- Engineers Guide To Microchip 2018Document36 pagesEngineers Guide To Microchip 2018mulleraf100% (1)

- The Power of Prayer English PDFDocument312 pagesThe Power of Prayer English PDFHilario Nobre100% (1)

- Chapter 3 Professional Practices in Nepal ADocument20 pagesChapter 3 Professional Practices in Nepal Amunna smithNo ratings yet

- DepEd Memorandum on SHS Curriculum MappingDocument8 pagesDepEd Memorandum on SHS Curriculum MappingMichevelli RiveraNo ratings yet

- 2010 Christian Religious Education Past Paper - 1Document1 page2010 Christian Religious Education Past Paper - 1lixus mwangiNo ratings yet