Professional Documents

Culture Documents

On The "Disappearance" of Hysteria A Study in The Clinical Deconstruction of A Diagnosis

Uploaded by

Caroline RynkevichOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

On The "Disappearance" of Hysteria A Study in The Clinical Deconstruction of A Diagnosis

Uploaded by

Caroline RynkevichCopyright:

Available Formats

On the "Disappearance" of Hysteria: A Study in the Clinical Deconstruction of a Diagnosis

Author(s): Mark S. Micale

Source: Isis, Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep., 1993), pp. 496-526

Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/235644 .

Accessed: 18/06/2014 06:25

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Isis.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

On the "Disappearance"

of Hysteria

A Study in the Clinical Deconstruction

of a Diagnosis

By Mark S. Micale*

Rest assured, hysteria is coming along, and one day it will

occupy gloriously the important place it deserves in the

sun.-Jean-Martin Charcot to Sigmund Freud (23 January

1888)

In reality, the patients have not changed since Charcot; it

is the words to describe them that have changed. -Georges

Guillain, La semaine des hopitaux (1949)

We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native lan-

guage.. . . Language is not simply a reporting device for

experience but a defining framework of it.-Benjamin

Whorf, "Language, Mind, and Reality" (1941)

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHIATRY, more than any other branch of the medical

sciences, is marked by the phenomenon of "rising" and "falling" diseases. Bur-

tonian melancholia in seventeenth-century England, the "vapors" of eighteenth-cen-

tury Parisian society, Beardian neurastheniain late nineteenth-centuryAmerica, and,

during our own time, psychogenic eating disorders-all are forms of psychiatric

illness that appear to have increased dramatically, even epidemically, in particular

times and cultural settings. Perhaps the best-known example is hysteria. After a long

and convoluted evolution across two and a half millennia of medical history,

including an efflorescence at the turn of the nineteenth century, hysteria is widely

held nowadays to have dwindled greatly in its rate of occurrence, if not to have

disappeared altogether. In the past fifteen years the rise to prominence of many

* Department of History, Yale University, 320 York Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06520.

Earlier versions of this essay were delivered in lecture form at the Wellcome Institute for the History

of Medicine (London); the Sixteenth International Symposium on the Comparative History of Medi-

cine-East and West (Mt. Fuji, Japan); the Department of Psychiatry, Beth Israel Hospital (Boston);

the Beaumont Medical Club, Yale University; and the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and

Aging Research, Rutgers University. I thank the members of those audiences-as well as Bill Bynum,

Phillip Slavney, Nancy Tomes, and Elizabeth Whitcombe-for their critical commentary.

Isis, 1993, 84: 496-526

?C1993by The History of Science Society. All rights reserved.

0021-1753/93/8401-0001$01 .00

496

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 497

nervous and mental maladies, including hysteria, has received considerable scholar-

ly attention. The converse question, of their alleged decline, remains largely

unexplored.1

The view of hysteria as a classically Victorian neurosis inexplicably on the wane

in the twentieth century has been common among critics, historians, and physicians

alike. As early as 1907 Fulgence Raymond, the noted Parisian professor of neurol-

ogy, designated the late nineteenth century as "the heroic period"of hysteria. In 1928

the poets Louis Aragon and Andre Breton, in one of their surrealist manifestos,

decreed hysteria "the greatest poetic discovery of the late nineteenth century." And

in the early 1950s Jacques Chastenet, the prominent historian of the French Third

Republic, labeled hysteria one of the primary "nevroses fin de siecle." Similarly,

doctors during the latter half of the nineteenth century matter-of-factly considered

hysteria the most common of the functional nervous disorders among females. Nine-

teenth-century medical publications on hysteria constitute a library of books, mono-

graphs, and articles. And a comprehensive historical catalogue of French psychiatric

dissertations indicates that no fewer than 20.5 percent of all theses written during

the nineteenth century dealt with hysterical disorders of one sort or another, the

largest percentage devoted to a single subject during any period.2 In the popular

historical imagination today, the late nineteenth century is the age of hysteria, with

Jean-Martin Charcot and Sigmund Freud serving as its representative personalities

and Paris and Vienna its quintessential capitals.

The contrast between the late nineteenth and the late twentieth centuries could

scarcely be greater. To be sure, many physicians continue to use the concept of

hysteria in specialized diagnostic settings-in reference to a personality trait or type;

in reference to a symptom that is formed functionally but mimics those caused by

somatic, particularly neurological, disease; or in reference to a psychoneurotic dis-

order characterizedby the habitual formation of symptoms in this manner.3 Yet neu-

rologists, psychiatrists, psychoanalysts, and clinical psychologists remain extremely

reluctant to employ the term in its two major noun forms, as they did so lavishly in

1 For a wide-ranging and interpretive review of the secondary literature pertaining to hysteria, with

an emphasis on recent scholarship, see Mark S. Micale, "Hysteria and Its Historiography-A Review

of Past and Present Writings," History of Science, 1989, 27:223-261, 319-351; and Micale, "Hysteria

and Its Historiography: The Future Perspective," History of Psychiatry, 1990, 1:33-124. Studies that

do address the topic of disease "decline" include Eugene Stransky, "On the History of Chlorosis,"

Episteme, 1974, 8:26-45; Robert P. Hudson, "The Biography of a Disease: Lessons from Chlorosis,"

Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 1977, 51:448-463; Barbara Sicherman, "The Uses of a Diagnosis:

Doctors, Patients, and Neurasthenia," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 1977,

32:33-54; Ian R. Dowbiggin, Inheriting Madness: Professionalization and Psychiatric Knowledge in

Nineteenth-Century France (Berkeley/Los Angeles: Univ. California Press, 1991), pp. 162-168; and

S. P. Fullinwider, Technicians of the Finite: The Rise and Decline of the Schizophrenic in American

Thought, 1840-1960 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1982).

2 Fulgence Raymond, in "Definition et nature de l'hysterie," in Comptes rendus de la Congres des

Medecins Alienistes et Neurologistes de France et des Pays de la Langue Francaise, Geneva and Lau-

sanne, 1-7 Aug. 1907, 2 vols. (Paris: Masson, 1907), Vol. 2, pp. 367-417, on p. 378; Louis Aragon

and Andre Breton, "Le cinquantenaire de l'hyst6rie (1878-1928)" (1928), rpt. conveniently in Histoire

du surrealisme: Documents surrealistes, ed. Maurice Nadeau (Paris: Seuil, 1948), p. 125; and Jacques

Chastenet, Histoire de la Troisieme Republique, 7 vols. (Paris: Hachette, 1955), Vol. 3: La Republique

triomphante, 1893-1906, Ch. 1. For the catalogue of dissertations see Arnaud Terrisse, "Une histoire

des theses de psychiatrie en France du d6but du XVIIe siecle a la veille de la Second Guerre mondiale,"

in Nouvelle histoire de la psychiatrie, ed. Jacques Postel and Claude Quetel (Toulouse: Privat, 1983),

p. 541.

3 On current-day diagnostic usages of the concept see Phillip R. Slavney, Perspectives on "Hysteria"

(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1990).

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

498 MARK S. MICALE

the past, to designate either a primary diagnosis or a patient (i.e., "It's a case of

hysteria," or "She's a hysteric"). To be specific: the dramatic, convulsive, poly-

symptomatic forms of the disorder found in Charcot's writings of the 1870s and

1880s and the gross and florid motor and sensory conversions displayed in Freud's

and Josef Breuer's well-known Studies on Hysteria of 1895 are regarded today as

extreme rarities.

This impression is confirmed by a computer search of the Index Medicus for writ-

ings on hysteria published in the second half of the twentieth century. The search

produces titles such as "The End of Hysteria" in the Annales Medico-Psychologiques

of 1960 and "Eclipse of Hysteria" in the British Medical Journal of 1965. A state-

ment by the editors of the British Medical Journal that appeared in 1976 describes

hysterical neuroses as "a virtual historical curiosity in Britain." Since the 1950s,

major psychiatric textbooks in the Anglo-American world have noted the gradual

decline of classic conversion hysteria. And for decades the literature of psycho-

analysis has bemoaned the disappearance of the grand hysterical patients of Freud's

time. "Where has all the hysteria gone?" queried one author in the Psychoanalytic

Review in 1979. A few years later a perplexed Jacques Lacan likewise asked: "Where

are the hysterics of former times, those magnificent women, the Anna 0.s and Emmy

von N.s? . . . What today has replaced the hysterical symptoms of previous times?"

In 1990 Phillip Slavney, a professor of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins University

School of Medicine who is sympathetic to retention of the hysteria concept, authored

a thorough and thoughtful book on the disorder in which the term appears in quo-

tation marks throughout the text. "This could well be the last book with 'hysteria'

in its title written by a psychiatrist," Slavney observes almost nostalgically.4

Perhaps more surprising than these remarks by physicians have been similar state-

ments by historians of the medical sciences. Ilza Veith, who produced the standard

intellectual history of hysteria in 1965, scrupulously charts the development of med-

ical thinking about hysteria from the ancient Egyptian papyri to early psychoana-

lytic theory; but she devotes only two closing paragraphsto the vexing question of

"the nearly total disappearance of the illness" today. Similarly, Etienne Trillat,

former editor of L'Evolution Psychiatrique, published a second major Histoire de

l'hyste'rie in 1986. He concludes his three-hundred-page study with four pages on

this subject, the final lines of which read like a historical epitaph: "And what is

left of hysteria today? Hysteria is of course dead, and it has taken its mysteries with

it to the grave."5

In recent decades two explanatory trends have developed in regard to the curious

clinical diminution of hysteria in the twentieth century. Customarily, if historians

address the "disappearance"of hysteria at all, they attributethe phenomenon to psy-

chological and sociocultural factors. Early in this century Freud, in a well-known

4A. Rouquier, "La fin de l'hysterie," Annales Medico-Psychologiques, 1960, 118(2):528; "Eclipse

of Hysteria," British Medical Journal, 29 May 1965, pp. 1389-1390; "The Search for a Psychiatric

Esperanto," ibid., 11 Sept. 1976, p. 601; Roberta Satow, "Where Has All the Hysteria Gone?" Psy-

choanalytic Review, 1979-1980, 66:463-477; Jacques Lacan, cited in Elisabeth Roudinesco, La bataille

de cent ans: Histoire de la psychanalyse en France, 2 vols. (Paris: Ramsay, 1982), Vol. 1, pp. 82-83

(here and elsewhere, translations into English are my own unless otherwise indicated); and Slavney,

Perspectives on "Hysteria," p. 190. For a textbook mention of the decline in hysteria see D. Wilfred

Abse, "Hysteria," in American Handbook of Psychiatry, ed. Silvano Arieti, 3 vols. (New York: Basic,

1959), Vol. 1, pp. 286-287.

5Ilza Veith, Hysteria: The History of a Disease (Chicago/London: Univ. Chicago Press, 1965), pp.

273-274; and Etienne Trillat, Histoire de l'hysterie (Paris: Seghers, 1986), p. 274.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 499

essay, argued that the prevailing social and moral conditions of his age were exacting

an inordinately high degree of sexual repression and in the process were producing

a race of neurasthenic men and hysterical women. During the past twenty-five years

Freud's analysis has been picked up and embroidered by many historians, social

scientists, and cultural critics, particularlyin the English-speaking world. According

to their interpretation,hysteria is a kind of pathological by-product of the Victorian-

Wilhelminian bourgeois social system with its sexual confinement, emotional oppres-

sion, and social suffocation. What one commentator has called "the Victorian hys-

terical mode," illustrated equally in the novels and the medical texts of the day,

often appears in this scholarship.6 Conversely, the conspicuous decline in rates of

hysterical illness during the twentieth century has, in this view, attended the passing

of those pernicious social and psychological conditions that generated an increase in

nervous complaints during the nineteenth century. In short, the disappearance of

hysteria is the result of de-Victorianization.

During the past two decades medical authors have posited a second explanation,

which might be called the argument from psychological literacy. According to this

interpretation, people were relatively primitive in their psychological processes be-

fore the twentieth century and found it easy to "somaticize" their anxieties-that is,

to express acute emotional distress through the formation of psychogenic physical

symptoms. However, with the coming of our "psychological society," and the popu-

larization of such concepts as unconscious motivation and psychosomatic sickness,

laypersons began to comprehend the psychodynamics behind hysterical conversion

symptoms, which thereafterfailed to elicit the desired social response and subjective

gratification. For secondary gain to work, it must remain unconscious in the mind

of the patient. As a result, according to this argument, people have been forced to

develop subtler and more sophisticatedmental mechanisms for coping with the stresses

of life. Typically, these new strategies center on the internalization of anxieties. This

line of analysis is often coupled with cross-cultural epidemiological data demon-

strating that hysterical neuroses currently prevail only in rural, lower-class, or third-

world environments and that the decline of hysterical conversion reactions within

industrialized and Westernized populations has been accompanied by a rise in de-

pressive and narcissistic disorders. This explanation has been popular with social and

6 Sigmund Freud, "'Civilized' Sexual Morality and Modem Nervous Illness" (1908), in The Standard

Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey with Anna Freud,

Alix Strachey, and Alan Tyson, 24 vols., Vol. 9 (London: Hogarth, 1959), pp. 177-204; and Alan

Krohn, Hysteria: The Elusive Neurosis (Psychological Issues, 45/46) (New York: International Univ.

Press, 1978), p. 189 (quotation).

7 The scholarly literature in this mold is large and diversified. A sampling includes Carroll Smith-

Rosenberg, "The Hysterical Woman: Sex Roles and Role Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America,"

Social Research, 1972, 39:652-678; Ann Douglas Wood. "'The Fashionable Diseases': Women's Com-

plaints and Their Treatment in Nineteenth-Century America," Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 1973,

4:25-52; John S. Haller, Jr., and Robin M. Haller, The Physician and Sexuality in Victorian America

(Urbana: Univ. Illinois Press, 1974), Ch. 1; Regina Schaps, Hysterie und Weiblichkeit: Wissenschafts-

mythen uber die Frau (Frankfurt:Campus, 1983), Ch. 9; Madeline L. Feingold, "Hysteria as a Modality

of Adjustment in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna" (Ph.D. diss., California School of Professional Psychology,

Berkeley, 1983); George Frederick Drinka, The Birth of Neurosis: Myth, Malady, and the Victorians

(New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), Chs. 1-6; Wendy Mitchinson, "Hysteria and Insanity in Women:

A Nineteenth-CenturyCanadian Perspective," Journal of Canadian Studies, 1986, 21:87-105; and Elaine

Showalter, The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830-1980 (New York: Pan-

theon, 1985), Chs. 5, 6. For expressions of this view by psychologists see Marc H. Hollender, "Con-

version Hysteria: A Post-Freudian Reinterpretationof Nineteenth-Century Psychosocial Data," Archives

of General Psychiatry, 1972, 26:311-314; and Krohn, Hysteria, Ch. 4.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

500 MARK S. MICALE

cultural critics, too, who have at times combined it with sharp critiques of the so-

cieties that generate these enculturated psychopathologies.8

Although not always well argued, the existing hypotheses for the disappearance

of hysteria--the arguments from sociosexual emancipation and psychological liter-

acy-assuredly contain elements of truth, and in the long run they will no doubt

contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the subject. My argument in this

article is offered as one factor in a larger, multicausal explanation. I believe, how-

ever, that the more we study the matter from a close and specifically medico-his-

torical perspective, the more we discover the insufficiency of the large and seductive

sociogenic interpretations posited thus far and the need to look elsewhere for an-

swers.

This need is apparenton a number of counts. For instance, both linear intellectual-

historical narratives of hysteria based on printed medical texts and specialized his-

torical studies derived from medical archival sources record the extensive existence

of hysterical disorders in pre-Victorian societies, including many societies that are

not noted for sexual and emotional repression.9 This suggests, if not the universal

existence of the malady, at least a considerable transculturalpresence. In the same

vein, recent scholarship has established that nineteenth-centurymedical professionals

widely applied the hysteria diagnosis to men, children, and working-class women-

in other words, to groups of individuals outside the putatively pathogenic social

milieu inhabited by middle-class Victorian women.'0 And the contention that people

8 Within the American psychiatric world, ideas related to the "argument from psychological literacy"

seem to have been enunciated first in Paul Chodoff, "A Re-examination of Some Aspects of Conversion

Hysteria," Psychiatry, 1954, 17:75-81. Subsequent writings include John L. Schimel et al., "Changing

Styles in Psychiatric Syndromes: A Symposium," American Journal of Psychiatry, 1973, 130:146-155;

J. G. Stefansson, J. A. Messina, and S. Meyerowitz, "Hysterical Neurosis, Conversion Type: Clinical

and Epidemiological Considerations," Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 1976, 53:119-138; Krohn, Hys-

teria, esp. pp. 174-176; and Marvin Swartz et al., "Somatization Disorder in a Community Population,"

Amer. J. Psychiat., 1986, 143:1403-1408. For statements by a medical historian and a sociologist see

Veith, Hysteria (cit. n. 5), pp. 273-274; and Pauline B. Bart, "Social Structure and Vocabularies of

Discomfort: What Happened to Female Hysteria?" Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1968, 9:188-

193. Among the cultural critics see Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an

Age of Diminishing Expectations (New York: Norton, 1978), Ch. 2, esp. pp. 41-43; and David Michael

Levin, ed., Pathologies of the Modern Self: Postmodern Studies on Narcissism, Schizophrenia, and

Depression (New York: New York Univ. Press, 1987).

9 Veith, Hysteria; Trillat, Histoire de l'hysterie (cit. n. 5); Sander Gilman, Helen King, Roy Porter,

George Rousseau, and Elaine Showalter, Hysteria beyond Freud (Los Angeles: Univ. California Press,

1993); Glafira Abricossoff, L'hysterie aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siecles (etude historique et bibliographique)

(Paris: G. Steinheil, 1897); Guenter Risse, "Hysteria at the Edinburgh Infirmary: The Construction and

Treatment of a Disease, 1770-1800," Medical History, 1988, 32:1-22; Katherine E. Williams, "Hys-

teria in Seventeenth-Century Case Records and Unpublished Manuscripts," Hist. Psychiat., 1990 1:383-

401; and Michael MacDonald, ed., Witchcraft and Hysteria in Elizabethan London: Edward Jorden and

the Mary Glover Case (Tavistock Classics in the History of Psychiatry) (New York: Routledge, 1991).

10On hysteria in men and children see Elisabeth Kloe, Hysterie im Kindesalter: Zur Entwicklung des

kindlichen Hysteriebegriffes (Freiburger Forschungen zur Medizingeschichte, 9) (Freiburg: Hans Fer-

dinand Schulz, 1979); K. Codell Carter, "Infantile Hysteria and Infantile Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-

Century German-LanguageMedical Literature,"Med. Hist., 1983, 27:186-196; Mark S. Micale, "Char-

cot and the Idea of Hysteria in the Male: Gender, Mental Science, and Medical Diagnosis in Late Nine-

teenth-CenturyFrance," ibid., 1990, 34:363-411; Micale, "Hysteria Male/Hysteria Female: Reflections

on Comparative Gender Construction in Nineteenth-Century France and Britain," in Science and Sen-

sibility: Gender and Scientific Enquiry, 1780-1945, ed. Marina Benjamin (London: Basil Blackwell,

1991), Ch. 7; and Janet Oppenheim, "ShatteredNerves": Doctors, Patients, and Depression in Victorian

England (New York/Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1991), Chs. 5, 7.

For application of the hysteria diagnosis to members of the working classes see Sicherman, "Uses of

a Diagnosis" (cit. n. 1), pp. 44, 52; Jan Goldstein, "The Hysteria Diagnosis and the Politics of Anti-

clericalism in Late Nineteenth-Century France," Journal of Modern History, 1982, 54:213-214; Risse,

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 501

in our own time are worldlier and more self-aware psychologically than their pre-

decessors remains suspect on many grounds and is difficult to document. Above all,

there is the problem of chronology. If the principal causes of the decline of hysteria

were those cited to date, we should expect to find a steady but gradual decrease in

hysterical disorders in the twentieth century as sexual liberalization and psycholog-

ical popularization advanced. To the contrary, the decline of hysteria as a workaday

diagnosis within European and North American medicine occurred rapidly after the

turn of the century and was effectively complete by World War I.

The historical record establishes this point unmistakably. An analysis of the med-

ical bibliography on hysteria as recorded comprehensively in the Index-Catalogue of

the Library of the Surgeon-General's Office reveals that the flood of French- and

German-language writings from the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s tapered off dramati-

cally in the late 1890s. By 1910 the flow was small, and, after a temporary surge

of publications on "hysterical disorders of war" between 1914 and 1918, it shrank

to a trickle during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. Amaud Terrisse's study of psy-

chiatric dissertations quantifies theses about hysteria by decade: in the 1870s, 49

dissertations written at French medical schools dealt centrally with hysterical dis-

orders; in the 1880s, 65; in the 1890s, 111; in the first decade of the twentieth

century, 85; in the 1910s, 13; in the 1920s, 9; in the 1930s, 1; and the 1940s, 3.11

Furthermore, the four major theoreticians of hysteria, whose names are associated

inseparably with the famous fin-de-siecle phase of the disorder-Jean-Martin Char-

cot, Hippolyte Bernheim, Pierre Janet, and Sigmund Freud-had either died or aban-

doned research on the subject by 1910.

The disappearance of hysteria was also registered directly by early twentieth-cen-

tury physicians working in a variety of medical, institutional, and national settings.

To my knowledge, the first statement by a medical author regarding the decline of

hysteria appeared in 1904, only a decade after the death of Charcot (1893) and the

publication of Studies on Hysteria by Freud and Breuer. Four years later Armin

Steyerthal, the director of a private health spa near Halle, Germany, predicted in a

pamphlet entitled What Is Hysteria? that "within a few years the concept of hysteria

will belong to history. . . . There is no such disease and there never has been."

And in 1914 Paul Guiraud, an asylum doctor in Tours, France, commented in the

Annales Me'ico-Psychologiques that "for some time now one has no longer dared

to speak of hysteria. Multiple theories clash and typical cases-have become rarerand

rarer." To much the same end, doctors during the interwar period reflected on the

theory of hysteria as if it were the product of an exotic, bygone era. In 1931

S. A. Kinnier Wilson of the National Hospital in London, who had studied with

Pierre Marie in Paris before World War I, reflected upon his experiences as a medical

student:

"Hysteria at the Edinburgh Infirmary," pp. 1-18; Micale, "Charcot and the Idea of Hysteria in the

Male," pp. 377-380; Edward Shorter, "Paralysis: The Rise and Fall of a 'Hysterical' Symptom," Jour-

nal of Social History, 1986, 19:572-573; and Williams, "Hysteria in Seventeenth-Century Case Rec-

ords," pp. 383-401.

1 Index-Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon-General's Office, 1st ser., 16 vols. (Washington,

D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885), Vol. 6, pp. 750-767; 2nd ser., 21 vols. (1902), Vol. 7, pp.

772-804; 3rd ser., 10 vols. (1926), Vol. 6, pp. 936-951; 4th ser., 11 vols. (1942), Vol. 7, pp. 966-

972. See also Terrisse, "Histoire des theses de psychiatrie" (cit. n. 2), p. 541. Tabulations from the

1930s and 1940s are derived from Patrick Genvresse and Jean-Claude Meurisse, Index ge'neral des theses

de psychiatrie publiees en langue fran,aise de 1934 d 1954 (Paris: Laboratoires Specia, 1988).

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

502 MARKS. MICALE

No longer do the "circushorses"of the Salpetri&re performbefore visitors as in the

palmy days of Charcot.No more does their contortedmusculaturerespondto the ap-

plicationof diverse metallic rods, as Gilles de la Tourettewas wont to demonstrate:

seldomindeedis the clinicianwitnessto the elaborateandprotractedhystericalfits whose

theatrical features were drawn with artistic skill by Paul Richer. . . . The times have

changedand we, both physicianand hysterics,have changedwith them.12

How, the historian can only wonder, have we gotten from the famous belle epoque

of hysteria in the closing decades of the nineteenth century to the virtual disappear-

ance of the disorder two decades later?

In this essay I pursue a line of investigation thus far unexplored. Instead of em-

phasizing social, sexual, and psychological factors, I focus on the rather technical

realms of medical nomenclature, nosology, and nosography. Specifically, I argue

that from 1895 to 1910 the hysteria diagnosis in its various nineteenth-century for-

mulations underwent a process of radical nosological and nosographical refashion-

ing-that is, a rapid change in what physicians interpretedas the clinical content of

the diagnosis and where they placed the disorder in the overall scheme of medical

classification-and that this drastic redefinition of the concept is what has created

the illusion that the pathological entity itself has disappeared.13 The key causes of

this diagnostic reconceptualization, I propose further, were scientific factors involv-

ing biomedical discoveries in etiological theory and diagnostic technique. At the

same time, these causes were reinforced and accelerated by a series of historically

specific sociological factors. By examining closely the evolution of European med-

ical systems during these years, and in particularFrench and German psychiatric and

neurological nosologies in the immediate post-Charcotian period, it is possible to

reconstruct this process in detail. In the past decade and a half, historians of science

and medicine have provided interesting and important analyses of the social con-

struction of diagnostic categories. This inquiry offers a study in the clinical decon-

struction of a diagnosis.

THE HYSTERIA DIAGNOSIS OF THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY

To comprehend the "decline" of hysteria during the past hundred years requires a

preliminary understandingof the diagnosis as it existed at the end of the nineteenth

12

Willy Hellpach, Grundlinien einer Psychologie der Hysterie (Leipzig: Engelmann, 1904), pp. 483-

494; Armin Steyerthal, Was ist Hysterie? Eine nosologische Betrachtung (Halle: Marhold, 1908), p. 26.

Paul Guiraud, "L'hyst6rie et la folie hysterique," Ann, Mc'd.-Psychol., 10th ser., 1914, 5:678-689, on

p. 678; and S. A. Kinnier Wilson, "The Approach to the Study of Hysteria," Journal of Neurology and

Psychopathology, 1931, 11:193-206, on pp. 194-195. For other early twentieth-century statements of

this development see Robert Gaupp, "Uber den Begriff der Hysterie," Zeitschriftfur die Gesamte Neu-

rologie und Psychiatrie, 1911, 5:457-466; Joseph Babinski, "Hyst6rie-pithiatisme,"Bulletins et Memoires

de la Societe Me6dicaledes H6pitaux de Paris, 3rd ser., 1928, 52:1507-1521; Antoine Giraud, La l6gende

de l'hysterie (Paris: Ficker, [1922]), Chs. 1, 2; and P. Hartenberg, "Que reste-t-il de l'hyst6rie?" Cli-

nique: Journal Hebdomadaire de M&decineet de Chirurgie Pratiques (Paris), 1933, 28:315-317.

13 A note on usage: in the analysis that follows, the term nosography denotes the assembling and

ordering of symptoms into disease entities and the differentiation of one disease entity from another.

This definition is in accord with the classic study by Knud Faber, Nosography: The Evolution of Clinical

Medicine in Modern Times (1923), 2nd rev. ed. (New York: Paul B. Hoeber, 1930). Nosology is the

study of the classification of diseases within general medical systems. So defined, the significance of

both nosology and nosography for diagnostic practice is obviously fundamental.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 503

century. A rich textual tradition representing something that may be interpreted as

hysteria stretches back to the Hippocratic canon of ancient Greece. Hysteria's long

and colorful heritage climaxed in the nineteenth century. The voluminous medical

literature of the time includes writings by neurologists, institutional psychiatrists,

and "nerve doctors," as well as gynecologists, surgeons, and general physicians. All

of the major previous paradigms of the disorder-gynecological, neurological, psy-

chological, and characterological-found expression. Although the literatureon hys-

teria spanned the century and was multinational in origin, physicians in France during

the final quarter of the century contributed the most commentary. Theorization on

the subject was dominated by Charcot, the celebrated Parisian neurologist who in

the 1870s and 1880s formed a coterie of young doctors and medical students around

him at the Salpetriere hospital to investigate in enormous and systematic detail what

he christened "the Great Neurosis." The disease picture of hysteria that has entered

the popular imagination today, and that is alleged to have disappeared, is primarily

the flamboyant version of the disorder that appeared in the writings of the Charcot

school. 14

The internal structure of the hysteria diagnosis as it existed a century ago was

distinctive in many ways. Two features deserve comment. First, it is important to

understand the relation between the causal and the symptomatological components

of the diagnosis in nineteenth-centuryEuropean medical thought. Charcot possessed

a clear etiological theory of hysteria. He believed that the disorder traced to a phys-

ical defect of the nervous system, such as a brain tumor or spinal lesion, that resulted

either from direct physical injury or defective neuropathic heredity. Such a defect,

or tare nerveuse, took the form of a "functional" lesion, by which he meant a path-

ophysiological alteration of unknown nature and location in the central nervous sys-

tem.

Nonetheless, nineteenth-centurytheories of hysteria remained wholly speculative.

Because of advances in pathology and bacteriology, doctors were achieving a new

level of etiological understandingfor many infectious and neurologicaldiseases. During

the late 1870s and 1880s laboratoryresearchers isolated specific microbial pathogens

for cholera, tuberculosis, gonorrhea, diphtheria, typhoid fever, and tetanus in dra-

matic succession. But precisely this sort of hard-and-fastinformation on the material

origins of the illness was lacking for hysteria. Nineteenth-century doctors hypothe-

sized about whether hysteria derived from an anatomical lesion, a molecular change,

a nutritional deficiency, or an electrophysiological irregularity in the brain, but in-

conclusively. Confronted, then, with the perpetual "problem of the missing lesion,"

as it was called, Charcot and his contemporaries had to "define" hysteria in a purely

symptomatological fashion, through the totality of its external clinical signs, which

they believed could be grouped into symptom clusters and then into discrete disease

categories. "What, then, is hysteria?" Charcot asked in his final publication on the

subject in 1892. "We do not know anything about its nature, nor about any lesions

producing it; we know it only through its manifestations and are therefore only able

14 See Veith, Hysteria (cit. n. 5): Trillat, Histoire de l'hyste'rie (cit. n. 5); George Wesley, A History

of Hysteria (Washington, D.C.: Univ. Press America, 1979); and Gilman et al., Hysteria beyond Freud

(cit. n. 9). No general history of hysteria in the nineteenth century exists. For the Salpetrian literature,

an extensive exposition may be found in Georges Gilles de la Tourette, Traite'clinique et therapeutique

de l'hyste'rie d'apres l'enseignement de la Salpetriere, 3 vols. (Paris: Plon, Nourrit, 1891-1895). See

also Georges Guillain, J. M. Charcot (1825-1893): Sa vie, son oeuvre (Paris: Masson, 1955), Chs. 13,

14; and Trillat, Histoire de l'hyste'rie, Ch. 6.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

504 MARK S. MICALE

to characterize it by its symptoms.'"15 Given the great range, drama, and mutability

of the symptoms of hysteria, nineteenth-century physicians were able to de-empha-

size intractable questions of causation and therapeutics and to concentrate on the

clinical phenomenology of the disorder. But it was precisely the etiological elusive-

ness of these concepts of hysteria, the lack of a strong causal theory to hold them

together, that would allow for their swift symptomatological dissolution in the future.

A second cardinal feature of nineteenth-century models of hysteria is their ex-

tremely expansive symptomatology. Unique among disorders, hysteria assumes its

form by aping other diseases. Consequently, the scope of its projected symptom-

atology has grown and shrunk and grown again over the centuries. Between 1872

and 1878, when Charcot first formulated his theory of hysteria, it was tightly delim-

ited. In the 1870s the diagnosis centered on the hysterical attack and the motor and

sensory "stigmata"-paralyses, contractures, anesthesias, hyperesthesias, and dys-

functions of vision and hearing. Then, over the next fifteen years, the diagnosis

underwent a nosographical inflation whereby its clinical boundaries were progres-

sively broadened. To the well-known neurological somatizations were added clinical

subcategories such as traumatichysteria, hysterical catalepsy, hysterical fugue, hys-

tero-neurasthenia,toxic hysteria, hysterical heart, hysterical anorexia, hysterical tic,

hysterical fever, and hysterical gastralgia. In short, as hysteria became the object of

more medical investigation, the accumulation of observations led not to a more rig-

orously defined clinical category, but only to more encompassing descriptive defi-

nitions. As a result, by the end of the nineteenth century the diagnosis resembled

an oversized and slightly vulgar late Victorian edifice-highly articulated in detail

and impressive to contemplate from afar, but impractically large and with an ex-

tremely shaky etiological foundation. In the hands of a new and ambitious generation

of medical architects, the nosographical structure would prove remarkably easy to

dismantle.

ORGANIC MEDICINE: CHANGES IN ETIOLOGICAL THEORY

AND DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUE

By the middle of the 1890s physicians in Europe and North America began to ob-

serve and to criticize the clinical overinclusiveness of the hysteria diagnosis. 16 In the

wake, then, of Charcot's death in 1893, how did the "clinical delimitation" of hys-

teria take place? Who were the main figures involved in the nosographical deflation

of the diagnosis? And to what new areas of medical theory did the diagnosis con-

tribute? I believe that three major medical categories absorbed elements of the di-

agnosis in its nineteenth-century versions. The first of these concerns general neu-

rological medicine, and most apparent in this regard is epilepsy.

15J M. Charcot and Pierre Marie, "Hysteria Mainly Hystero-Epilepsy," in A Dictionary of Psycho-

logical Medicine, ed. D. Hack Tuke, 2 vols. (London: Churchill, 1892), Vol. 1, p. 628. Charcot excelled

at this procedure and utilized it in the construction of other disease pictures as well. In his obituary

notice about Charcot, Freud states that Charcot called the method of formulating symptomatological

syndromes "practicing nosography": Sigmund Freud, "Charcot" (1893), in Freud, Standard Edition,

trans. Strachey et al. (cit. n. 6), Vol. 3, p. 12.

16 See Pierre Janet, "Quelquesd6finitions r6centes de l'hysterie," Archives de Neurologie, 1892, 25:417-

438, 1893, 26:1-29, on pp. 17, 18; Smith Ely Jelliffe, cited in S. A. Kinnier Wilson, "Some Modem

French Conceptions of Hysteria," Brain, 1911, 33:292-338, on p. 308; and Meyer Solomon, "The

Clinical Delimitation of Hysteria," New York Medical Journal, 1915, 102:944, 945.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 505

Owsei Temkin has stated that the medical conception of the relation between epi-

lepsy and many other convulsive disorders, including hysteria, remained hopelessly

confused before the middle of the nineteenth century. Nineteenth-century neurolo-

gists were keenly aware of the age-old confusion between epilepsy and hysteria, and

Charcot struggled all his life with the differential diagnosis of the two disorders. As

a part of this effort he formulated a set of criteria, based purely on clinical obser-

vation, that he believed distinguished the epileptic fit from the hysterical paroxysm.

But the imitative capabilities of the hysterical patient were formidable. In many Eu-

ropean hospitals hysterical and epileptic patients had been housed together in the

same wards for years. Charcot himself first became interested in hysterical disorders

at the Salpetriere in 1870 when he attempted to separate "non-insane hystero-epi-

leptic" patients from the genuine epileptics. In addition, his printed case presenta-

tions and unpublished clinical records show that a percentage of his hysterical pa-

tients during the 1880s came from households with epileptic family members. To

account for the clinical ambiguity between the two diseases, Charcot applied the

hybrid diagnostic label "hystero-epilepsy" to a large number of his patients-an

unsatisfactory term and concept that he abandoned in his later years. 17 In light of

these facts, it was almost inevitable that Charcot, like generations of physicians be-

fore him, would confound elements of the two disorders in formulating his theory

of hysteria.

During the second half of the nineteenth century the British neurological com-

munity conducted superb clinical work on epilepsy and began to seize the lead from

the French. In particular, Charcot and the English neurologist William Gowers dis-

agreed sharply over the concept of la grande attaque hyste'ro-e'pileptique.For Char-

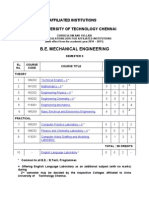

cot, the hysterical attack was an elaborate four-part affair (see Figure 1). The first

stage took the form of an epileptoid seizure marked by tonic contractures and clonic

spasms. This was followed by a stage of "large movements" (grands mouvements),

in which the patient assumed striking contorted postures, including the arched-back,

or arc de cercle, position; a stage of attitudes passionnelles, characterized by the

hallucinatory reenactment of past emotional events; and a stage of delirious with-

drawal, which could last for hours or even days. Gowers, however, like most of his

colleagues in Britain, was skeptical of the work of the Paris school; he believed that

Charcot's first stage represented the essential pathological event, a true epileptic

seizure, with the subsequentphenomena-Charcot's second, third, and fourth stages-

forming an elaboratepsychological sequelae to the fit. In Epilepsy and Other Chronic

Convulsive Disorders (1881) Gowers discusses these cases at length, referring to

them as "epilepsy with coordinated hysteroid convulsions." 18 So far as I can deter-

mine, the two men observed the same clinical picture but interpretedit differently-

17

Owsei Temkin, The Falling Sickness: A History of Epilepsy from the Greeks to the Beginnings of

Modern Neurology, 2nd rev. ed. (Baltimore/London: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1971), pp. 351-359.

See also Louis Paul Crouzet, "Les epileptiques a la Salpetriere, division des alienes: De l'application

de la loi sur les alienes" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Paris, 1871); J.-M. Charcot, "De l'hystero-epilepsie," in

Le!ons sur les maladies du systeme nerveux faites a la Salpetriere, comp. D. M. Bourneville (Paris:

Adrien Delahaye, 1872-1873), pp. 321-337; and Charcot, "Grande hysterie ou hystero-epilepsie," in

Le!ons du mardi d la Salpetriere: Professeur Charcot: Policliniques, 1887-1888 (Paris: Aux Bureaux

du Progres Medical, Delahaye & Lecrosnier, 1887 [sic]), pp. 173-179.

18 Desire-Magloire Bourneville and Paul Regnard, Iconographie photographique de la Salpetriere, 3

vols. (Paris: Delahaye & Lecrosnier, 1876-1880); Paul Richer, Etudes cliniques sur la grande hystirie

ou l'hystero-epilepsie, 2nd enlarged ed. (Paris: Delahaye & Lecrosnier, 1885); and W. R. Gowers,

Epilepsy and Other Chronic Convulsive Disorders (London: Churchill, 1881), Chs. 6, 7.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

506 MARK S. MICALE

P-a- It Pifia& pibpa-d- 2! Pnrod. de ebwndgn. S!PM iXO& p> _ VPoe;0:iietti0i; .0

A B C D Cf - 7~ -0 H 3 K ? L :g;$: D

VL~~~~~~~~LV

.. ,

34..

tiS;~~ A.4, .^CE ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~

Figure 1. Bodilypositions in the four main stages of the classic Charcotianfit. (FromPaul

Richer,Etudes cliniquessur la grande hysterie ou l'hystero-epilepsie,2nd rev. and enlarged ed.

[Paris:Delahaye & Lecrosnier,1885], unnumberedpage.)

Charcot as epileptiform hysteria, Gowers as organic epilepsy with a long psycho-

logical aftermath in what today would be called the postictal period.

During the last three decades of the nineteenth century the French theory of epi-

lepsy predominated in medical thinking on the Continent. In the Salpetrian literature,

nearly a quarter of the cases carry the mixed diagnosis "hystero-epilepsy." In the

twenty years following Charcot's death, however, Gowers's interpretation was in-

creasingly adopted in Germany, France, and elsewhere. A sequence of texts on the

subject, including works by Charles Fere (1892), G. Bonjour (1907), G. Bouche

(1908), Paul Guichard(1908), and Theodore Diller (1910) and culminatingin Joachim

Caspari's Clinical Study of the DifferentialDiagnosis of Epilepsy and Hysteria (1916),

reveals a growing interest in the concept of "hysterical epilepsy" and "post-epileptic

hysteria" in preference to the earlier view of Charcot. What Gowers and his followers

surmised from observation at the bedside-namely, that many of the most dramatic

cases of hysteria involved an underlying organic element-was borne out in the late

1920s with the advent of electroencephalography, which eventually allowed for a

much finer differentiationbetween hysteria and the various epilepsies, including what

by the 1950s was termed temporal lobe epilepsy.19

'9 Charles Fere, Epilepsie (Paris: Gauthier-Villars/Masson, 1892), Chs. 6, 8, 12, 18; G. Bonjour,

"Diagnostic diffdrentiel des crises dpileptiques et des crises hysteriques: Un sympt6me nouveau,"

L'Encephale, 1907, 2:263-264; G. Bouche, "Diagnostic et prognostic de 1'epilepsie essentielle," Jour-

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 507

Additionally, the early twentieth century brought a new clinical and theoretical

interest in "the psychology of epilepsy." A majority of nineteenth-century physi-

cians, including Charcot and his circle, reacted against the former confusion between

hysteria and epilepsy by striving diagnostically to distinguish true epilepsy from its

hysterical counterfeits. In contrast, in a number of pioneering essays from the 1870s

and 1880s, the English neurologist J. Hughlings Jackson described the exceptional

mental states that may follow an epileptic discharge. During the first decade of the

twentieth century English and German physicians, following Jackson's lead, began

to explore the complex neuropsychiatric interactions that may develop between epi-

lepsy and hysteria within the same patient. An importantpart of this work involved

investigating the remarkable variety of behaviors-stupor, transient amnesia, sen-

sory hallucinations, confusional states-that may occur in the postconvulsive period

of epilepsy and that are today grouped under the heading "epileptic psychosis." (In

our own time, this line of research has produced the concepts of the "functional

overlay" and the "psychogenic pseudo-seizure.") In other words, the scope of clin-

ical phenomena classified as epileptic during the early twentieth century was en-

larging steadily, and this expansion almost certainly took place at the expense of the

hysteria diagnosis.20

The past connections between the diagnoses of hysteria and syphilis are no less

complex and significant. From the 1820s onward a debate raged in the European

medical community over the causal and clinical relations between syphilis and in-

sanity. Nineteenth-century physicians, including several who wrote about hysteria,

were well aware of many of the neural manifestations of syphilis that could develop

after a long period of latency. Charcot himself conducted importantresearch on optic

atrophy and on meningitis with convulsions of syphilitic origin. On this point, how-

ever, Charcot's celebrated clinical intuition failed him, and he proved unable to make

the etiological connection between syphilitic infection and either tabes dorsalis or

general paralysis of the insane. In 1876 the French venereologist Alfred Fournier

first proposed the syphilitic origins of tabes. He then turned to general paresis and

accumulated clinical data on the subject during the 1880s. In a historic statement to

the Paris Academy of Medicine in October 1894, and later that year in his book

Parasyphilitic Affections, Fournier announced the results of his study, which estab-

lished a strong statistical correlation between infection with syphilis and the subse-

quent development of general paralysis.21

nal Medical de Bruxelles, 1908, 13:601-607; Paul Guichard, "De l'hyst6rie a forme d'6pilepsie partielle

et 6pilepsie jacksonienne chez une hyst6rique, diagnostic diff6rentiel" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Montpellier,

1908); Theodore Diller, "Differential Diagnosis between Epilepsy and Hysteria and Their Mutual Rela-

tionship, " International Clinics, 20th ser., 1910, 4:177-188; Joachim Caspari, Klinische Beitrdge zur Dif-

ferentialdiagnose zwischen Epilepsie und Hysterie (Berlin: Ebering, 1916); and Hans Berger, "Uber das

Elektrenkephalogrammdes Menschen, " ArchivfiirPsychiatrie undNervenkrankheiten, 1929,87:527-570.

20 J. Hughlings Jackson, "On Temporary Mental Disorders after Epileptic Paroxysms" (1875), "On

Epilepsies and on the After-Effects of Epileptic Discharges" (1876), and "On Post-Epileptic States: A

Contribution to the Comparative Study of Insanities" (1889), all rpt. in Selected Writings of John Hugh-

lings Jackson, ed. James Taylor, 2 vols. (New York: Basic, 1958), Vol. 1, pp. 119-134, 135-161,

366-384. Pertinent to this point is Esther M. Thornton's Hypnotism, Hysteria, and Epilepsy: An His-

torical Synthesis (London: William Heinemann, 1976). Thornton advances the interesting thesis that the

most dramatic cases of grande hysterie in the nineteenth century were actually cases of temporal lobe

epilepsy in which attacks were elicited though the procedures employed by hypnotists in public dem-

onstrations.

21 Alfred Fournier, De l'ataxie locomotrice d'origine syphilitique (Paris: Masson, 1878); and Fournier,

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

508 MARK S. MICALE

During the same years that Fournier was conducting his research on the etiology

of syphilis, the Charcot school was deeply engaged in its hysteria studies. Charcot

dissented vehemently from Fournier's findings. Throughout his lifetime he insisted

that syphilis, tabes, and general paralysis, as well as other nervous and neurological

diseases including hysteria, were separate manifestations of a more basic neuropathic

heredity. Primary and secondary venereal infections might operate as agents pro-

vocateurs of these disorders, but they represented fundamentally different maladies

that were unrelatedcausally. As Fournierpointed out in two chapters of Parasyphili-

tic Affections, the result of this misconception was widespread diagnostic confusion

between certain cases of acute hysteria and advanced neurosyphilis.22Again, how-

ever, European medical thinking moved away from Charcot. As with Gowers and

epilepsy, what Fournier had sensed clinically in the 1870s was established conclu-

sively through technical advances in the following generation. In 1905 Fritz Schau-

dinn and Erich Hoffmann, in Berlin, observed microscopically the Spirochaeta pal-

lida, the actual syphilitic organism, in human tissue from a primary syphilitic lesion.

The following year August Wassermann, a serologist also situated in the German

capital, used the latest staining techniques to develop the first blood test for the

presence of syphilitic antibodies. And in 1913 Hideyo Noguchi and J. W. Moore,

working at the Rockefeller Institute in New York City, used the most recent histo-

pathological methods to isolate the spirochete in the brain tissue of a paretic patient.23

Epidemiologically, the connection between the diagnoses of syphilis and hysteria

was by no means as remote a hundred years ago as it appears today. In late nine-

teenth-century European medicine both disorders were seen as afflictions of the cen-

tral nervous system. Moreover, an unprecedented, epidemical rise in cases of syphilis

occurred in many urban areas in Europe during this period-that is, during the same

years as the upsurge in hysteria. In the 1850s Fournier had claimed that as much as

15 percent of the general adult population of Paris was infected with syphilis. To

the same effect, Claude Quetel, in a recent historical account of syphilis, cites a

rapport ge'ne'ralundertaken by the French Ministry of the Interior in 1874, which

found that 2,619 patients in municipal mental hospitals across the nation suffered

from general paralysis; this represents 6.2 percent of the population of French public

asylums. Quetel finds further, from archival medical records, that in certain Parisian

institutions specializing in the disease, such as the Charenton asylum, as many as

Les affections parasyphilitiques (Paris: Rueff, 1894). Tabes dorsalis, designated in nineteenth-century

French medicine as locomotor ataxia, refers to syphilis of the spine, whereas general paralysis of the

insane, also known as general paresis or dementia paralytica, signifies the meningoencephalitis of tertiary

neurosyphilis. Both are progressive neurodegenerative diseases. On the debate over the relations between

syphilis and insanity see Gregory Zilboorg with George W. Henry, A History of Medical Psychology

(New York: Norton, 1941), pp. 526-551.

22 For Charcot's view see Charcot, "Syphilis, ataxie locomotrice progressive, paralysie faciale," in

Lecons du mardi (cit. n. 17), pp. 1-11; Georges Gilles de la Tourette, "Hyst6rie et syphilis," Progres

Medical, 2nd ser., 1887, 6:511-512; and Jean-Martin Charcot to Sigmund Freud, 30 June 1892, in

"'Mon Cher Docteur Freud': Charcot's Unpublished Correspondence to Freud, 1888-1893," Bull. Hist.

Med., 1988, 62:572-575, 587-588. Cf. Fournier, Les affections parasyphilitiques, Chs. 16 and 17,

where he specifically dissents from the view of the Salpetriere school.

23 Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann, "Vorlaufiger Bericht uber das Vorkommen von Spirochaeten

in syphilitischen Krankheitsproduktenund bei Papillomen," Arbeiten aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheit-

samte, 1905, 22:527-534; A. Wassermann, A. Neisser, and C. Bruck, "Eine serodiagnostische Reaktion

bei Syphilis," Deutsche Medizinische Wochenscrift, 1906, 32:745-746; and Hideyo Noguchi and

J. W. Moore, "A Demonstration of the Treponema Pallidum in the Brain in Cases of General Paralysis,"

Journal of Experimental Medicine, 1913, 17:232-238.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 509

35 percent of the patients were so afflicted. In 1913-the year that Noguchi and

Moore announced their results-Emil Kraepelin observed similarly that paretics con-

stituted an average of 10 to 20 percent of all admissions to mental hospitals in Ger-

many.24 In short, during the final third of the nineteenth century patients with ad-

vanced syphilis were intermixed with general institutionalizedpsychiatric populations,

which also included many cases diagnosed as severely hysterical.

Equally relevant are the clinical similarities between the two maladies. In the nine-

teenth-century medical literatureon hysteria, acute paralytic disturbances are among

the most common symptoms. The onset of general paresis, like hysteria, may be

characterized by convulsive seizures, double vision, loss of pain sensation in scat-

tered areas of the body, and sensory ataxias, as well as exaggerated emotional be-

haviors. The situation was furthercomplicated by the fact that hysterical symptoms,

especially monoplegias, hemiplegias, and paraplegias, often appear in conjunction

with syphilis, especially at the outset of the secondary stage of infection. Fournier

speaks of these cases as "parasyphilitichysteria." One of his students believed that

the associations between the two ailments were so close and common that a special

mixed diagnosis was in order. Finally, it may be relevant to consider the patient

population from which the leading nineteenth-century theory of hysteria derived. In

Charcot's writings, roughly 40 percent of the case histories of hysteria concern adult

males from the working classes, a population in which the occurrence of syphilis

was exceptionally high at the time.25 Clearly, the medical historian can only spec-

ulate on this point; but it appears likely that a not-insignificant number of individuals

included a century ago in the French medical literature as hysterical were in fact

afflicted with "the great imitator" in its advanced stages. Once again, the technical

means for distinguishing definitively between neurosyphilis and other neurological

and psychiatric disorders, and therefore for recategorizing these cases, became avail-

able to the generation of practitioners following Charcot.26

It is impossible to review here every medical development of the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries that bore on the hysteria diagnosis; but in retrospect

we can see that the process occurred in many areas. In 1895 Karl Roentgen discov-

ered the X-ray. A major diagnostic tool for detecting structuraldamage to the body,

including cranial injury, was now at the disposal of doctors. The separation of the

numerous cases of "post-traumatichysteria" from those involving structuralphysical

injury was made much easier. In 1896 Joseph Babinski discovered the cutaneous

plantarreflex that still bears his name ("Babinski's sign" or "Babinski's toe reflex").

A simple but reliable procedure was now available for separating most hysterical

hemiplegias and paraplegias from paralyses of organic, especially cerebrovascular,

24 Alfred Fournier, cited in Roger L. Williams, The Horror of Life (Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press,

1980), p. 49; Claude Qu6tel, History of Syphilis, trans. Judith Braddock and Brian Pike (Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1990), p. 161; and Emil Kraepelin, General Paresis, trans. J. W. Moore

(New York: Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing, 1913), pp. 138, 139.

25 Fournier, Les affections parasyphilitiques (cit. n. 2 1), pp. I 1- 118; M. Hudelo, "Hyst6ro-syphilis,"

Annales de Dermatologie et de Syphiligraphie, 3rd ser., 1892, 3:839-842; and Micale, "Charcot and

the Idea of Hysteria in the Male" (cit. n. 10), pp. 370-373, 377-380.

26 Psychiatric textbooks published after the work of Noguchi and Moore also registered the diagnostic

significance of these technical advances for psychological medicine. See William White, Outlines of

Psychiatry, 5th ed. (New York: Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing, 1915), p. 117;

Francis Dercum, A Clinical Manual of Mental Diseases, 2nd rev. ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders, 1918),

pp. 267-268; and Aaron Rosanoff, Manual of Psychiatry, 5th rev. ed. (New York: John Wiley, 1920),

pp. 395-396.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

510 MARK S. MICALE

origin.27To cite one furtherexample, Charcot and his student Georges Guinon wrote

often during the 1880s about the concept of "toxic hysteria." The cases they pre-

sented under this rubric were produced by excessive exposure to lead, mercury, and

carbon disulfide in the environment. Over the next two decades many of the mental

and physical symptoms they discussed in these cases came to be understood as the

effects of chemical poisoning and were regrouped under the heading "toxic psy-

choses. ,28

Hysteria, it is often said today, is a "diagnosis of exclusion." By definition, it

can be applied only when all possible anatomical and physiological explanations for

the symptoms have been ruled out. As a consequence, the legitimate sphere of the

diagnosis (some critics would say of psychodynamic psychiatry as a whole) may be

fated continually to contract as the understanding of organic illness expands. In the

ongoing appropriationof the mental by the physical, the early twentieth century was

a highly active period. The most astute observers were aware of the change and its

implications. In 1914 Paul Guiraud of Tours wrote, "When we have completed the

clinical analysis of all the hysterical symptoms, when we have given to each malady

what belongs to it, who knows if anything will still remain of hysteria?"29

INSTITUTIONAL PSYCHIATRY AND THE RISE OF GERMAN-LANGUAGE THEORIES

OF THE PSYCHOSES

At the same time that the old "citadel of hysteria" was under attack from outside

the domain of psychological medicine, it was also being undermined by innovative

medical ideas within the psychiatric profession. If we inspect the tables of contents

of French and German psychiatric textbooks from around 1915 and contrast them

with their counterparts from a generation earlier, we find that the two sources are

remarkably dissimilar. A number of diagnostic categories from the earlier sources

are used much less frequently or have fallen away altogether, while new ones have

appeared in their place. Easily the largest new nosological unit in the later works is

formed by the psychoses, in the present-day sense of the word. These theories of

the psychoses make up the second major area of medicine that laid claim to the old

27 Babinski commented specifically on the implications of his discovery for hysteria in "Des signes

permettant le diagnostic differential entre les affections nerveuses hyst6riques et organiques," Clinique,

1911, 6:551-553.

28 From 1895 to 1905 a spate of medical dissertations-many of them from provincial medical fac-

ulties-probed the differential diagnosis of hysteria and other organic diseases too. See Maurice Pignet,

"Pseudo mal de Pott (mal de Pott hyst6rique)" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Lyon, 1895); Domitian Glinenau,

"Rapportsde 1'hyst6rie avec la tuberculose pulmonaire" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Paris, 1896); J. Nouaille,

"Contributiona l'tude de I'hysterie senile (hyst6rie chez les vieillards)"(M.D. thesis, Univ. Paris, 1899);

J. Combes, "Contribution au diagnostic de l'hyst6rie cofncidant avec le syndrome de la sclerose en

plaques ou l'hemiplegie" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Toulouse, 1901); Emile Fouquet, "Contributiona 1'etude

de la pseudo-scl6rose en plaques d'origine hyst6rique" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Lille, 1901); Pierre Aubry,

"Des rapports de la chor6e avec l'hysterie et en particulier de la choree rythmee cons6cutive a la chor6e

de Sydenham" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Toulouse, 1903); and Henri Bernadicou, "Contributiona l'etude des

rapports symptomatiques entre le tabes et l'hyst6rie" (M.D. thesis, Univ. Paris, 1904).

29 Guiraud, "L'hyst6rie et la folie hyst&rique"(cit. n. 12), p. 684. See also Thomas Buzzard, On the

Simulation of Hysteria by Organic Disease of the Nervous System (London: Churchill, 1891), pp. vii,

113; and Wilson, "Some Modem French Conceptions of Hysteria" (cit. n. 16), p. 337.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 511

territoryof hysteria. They were almost entirely the product of the German-speaking

medical communities.30

During the first half of the nineteenth century the generic diagnostic categories

that had existed in Western psychiatric medicine since ancient times-mania, mel-

ancholia, delirium, and dementia-began to break down into more specialized cat-

egories. As part of this process, the notion of "hysterical insanity" and "hysterical

mania" (la folie hyste'rique, la manie hyste'rique,das hysterische Irresein) emerged

in French, German, and British medicine during the middle of the century. In works

by Wilhelm Griesinger(1845), B. A. Morel (1852-1853; 1860), L. V. Marce (1862),

and J. J. Moreau de Tours (1869), hysterical insanity represented a loose assortment

of behaviors-usually dramatic, erratic, or erotic in nature-that accompanied cer-

tain cases of nervous and mental illness in female patients. Among asylum physi-

cians, the concept of hysterical insanity proved serviceable, and later in the century

it cropped up in psychiatric treatises by Richard von Krafft-Ebing, H. Schiule, Jules

Falret, Henri Legrand du Saulle, Valentin Magnan, Henry Maudsley, and Thomas

Clouston.3'

Then, in 1874, Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum, the director of a private mental hospital

in Gorlitz, Silesia, published a short monograph entitled Catatonia, or Tension In-

sanity. In this study Kahlbaum described a clinical syndrome for which he coined

the term Katatonie. Kahlbaum's catatonia was in part a reformulation of the concept

of hysterical insanity from the preceding generation. In addition to the stuporous

states the word signifies today, the syndrome included high levels of anxiety, radical

mood shifts, and various thought disorders. Kahlbaum proposed a number of cata-

tonic phases, one of which he called the stage of "patheticism," or pathetic behav-

iors. The pathetic stage was marked by "theatricalpostures and gesticulations," "sen-

sual playfulness," "a tendency to clownishness," "expansive moods that permeate

speech, actions, and gestures," and "histrionic exaltation, sometimes in the form of

a tragic-religious ecstasy." A number of these features-notably, the "clownishness"

and quasi-religious behaviors-were at this same time being incorporatedby Charcot

into his new hysteria formulation. Kahlbaum also noted in his conspectus that several

of the mental phenomena he chose to classify as catatonic had been described a few

years earlier by one of his colleagues, Ewald Hecker, under the heading "hebe-

phrenia."32Interestingly, the ideas and terminology of Hecker and Kahlbaum went

almost entirely unnoticed during the 1870s and 1880s.

Twenty years later, however, their work was integrated into the new, more am-

bitious, and far more successful psychiatric system of Emil Kraepelin. Kraepelin,

"the Linnaeus of psychiatry," set himself the task of establishing a comprehensive

plan of classification for mental medicine. The psychiatric system that resulted from

30 To the best of my knowledge, the first person to perceive the clinical continuities between the

decline of hysteria and the rise of the psychoses was Henri Baruk, "L'hyst6rie et les fonctions psy-

chomotrices," in Comptes rendus de la Congres des Medecins Alie'nistes et Neurologistes de France et

des Pays de la Langue Francaise, Brussels (Paris: Masson, 1935), pp. 3-7, a source to which the

following several pages are much indebted. For the phrase "citadel of hysteria" see Paul Hartenberg,

"Les nouvelles idees sur l'hyst6rie," Presse Medicale, 1907, 15(2):468-469, on p. 469.

31 Paul Bercherie, "Le concept de folie hysterique avant Charcot," Revue Internationale d'Histoire

de la Psychiatrie, 1983, 1:47-58.

32 Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum, Die Katatonie; oder, das Spannungsirresein: Eine klinische Form psych-

ischer Krankheit (Berlin: August Hirschwald, 1874), descriptions on pp. 31-36; and Ewald Hecker,

"Die Hebephrenie: Ein Beitrag zur klinischen Psychiatrie," Archivfur Pathologische Anatomie und Phys-

iologie undfiir Klinische Medicin, 1871, 52:394-429.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

512 MARK S. MICALE

his work was enormously influential, not least in American psychiatry, and to a large

extent is still with us today. The most importantof Kraepelin's diagnostic categories

were dementia praecox and manic-depressive psychosis.

Kraepelin presented his taxonomic plan in his famous Lehrbuch. His textbook ran

to eight editions between 1883 and 1915 and so provides an excellent overview of

the contemporary history of European psychiatric nosology. The most striking fea-

ture of the work is its expansion from edition to edition. The first edition of the

book, which was entitled Compendium of Psychiatry, had 384 pages. The second,

third, and fourth editions, published respectively in 1887, 1889, and 1893 as A Short

Textbook of Psychiatry for Students and Physicians, were 540, 584, and 702 pages

in length. In the fourth edition, which appeared the very year of Charcot's death,

Kraepelin formally introduced the term dementia praecox, which he borrowed from

Morel. He presented the concept in a 10-page discussion of the three subforms (the

others were catatonia and paranoia) of the "degenerative psychological processes."

In 1896 the fifth edition, an 825-page Textbook of Psychiatry for Students and Phy-

sicians, appeared; here dementia praecox ranked above catatonia and paranoia in a

15-page passage. In the well-known sixth edition of 1899, in two volumes, Kraepelin

included a 75-page description of dementia praecox and his first chapter-length dis-

cussion of the manic-depressive psychoses. Edition seven of the Lehrbuch, which

incorporated chapters of approximately 100 pages apiece on dementia praecox and

manic-depressive psychoses, was published in 1903-1904. The final edition ap-

peared between 1909 and 1915. It consisted of no fewer than four weighty volumes

totaling over 3,000 pages. The sections on dementia praecox and manic-depressive

psychoses had swollen to 301 and 212 pages, respectively; together, they were longer

than the entire first edition of the work.33Few works exhibit more clearly the strong

classificatory impulse that has animated the history of psychiatry.

As Kraepelin's textbook grew during the late nineteenth and early twentieth cen-

turies, and with it the concepts of dementia praecox and manic-depressive psychoses,

the historian may inquire: Where did Kraepelin find the building blocks for his vast

nosographical synthesis? Without doubt, the historical origins of Kraepelinian theory

are diverse; but I want to suggest that Kraepelin drew in part on the nineteenth-

century hysterias. Although French medicine boasted a rich, unbroken tradition of

commentary about hysteria from the preceding two hundred years, and the British

had produced a smattering of important texts from the time of Robert Burton and

Edward Jorden onward, the German-speakinglands possessed no indigenous national

discourse on hysteria until the end of the nineteenth century. The 1880s brought a

sudden increase of interest in the subject, and by the 1890s the German-language

literatureequaled the French in quantity. At first German and Austrian doctors were

inspired directly by Charcot's conception of the disorder, which they liked because

3 Emil Kraepelin, Compendium der Psychiatrie: Zum Gebrauche fur Studirende und Aerzte (Leipzig:

Abel, 1883); Kraepelin, Psychiatrie: Ein kurzes Lehrbuch fdr Studirende und Aerzte, 2nd ed. (Leipzig:

Abel, 1887); Kraepelin, Psychiatrie: Ein kurzes Lehrbuchfur Studirende und Aerzte, 3rd rev. ed. (Leip-

zig: Abel, 1889); Kraepelin, Psychiatrie: Ein kurzes Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte, 4th rev. ed.

(Leipzig: Abel, 1893), pp. 435-445; Kraepelin, Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte,

5th rev. ed. (Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1896), pp. 426-441; Kraepelin, Psychiatrie: Ein Lehr-

buch far Studirende und Aerzte, 6th rev. ed., 2 vols. (Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1899), Vol.

2, pp. 137-214, 359-425; Kraepelin, Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte, 7th rev.

ed., 2 vols. (Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1903-1904), Vol. 2, pp. 176-283, 496-589; and Krae-

pelin, Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuchfar Studirende und Aerzte, 8th rev. ed., 4 vols. (Leipzig: Johann Am-

brosius Barth, 1909-1915), Vol. 3, pp. 668-972, 1183-1395.

This content downloaded from 195.34.78.244 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 06:25:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE "DISAPPEARANCE" OF HYSTERIA 513

its neurocentricetiology and symptomatology accorded well with the organicist med-

ical philosophy prevailing in their profession. Then, during the 1890s a number of

researchers, including Adolph von Struimpell,Paul Mobius, Breuer, and Freud, grad-

ually broke with the Salpetrian model and advanced their own more psychologized

theories of the disorder.34

Kraepelin, in formulating his ideas about dementia praecox and manic-depressive

disorder, drew on both the mid-century medical writing about hysterical insanity

(especially that of Griesinger) and the recent French and German literature on hys-

teria. The evidence for this lineage is strongly suggestive. If we compare many of

the images in the Iconographie photographique de la Salpe?trie're,published in 1876-

1880, with those in the classic ninth chapter on dementia praecox in the sixth edition

of Kraepelin's textbook (1899), we find that the clinical descriptions and pictorial

representationsare much alike.35Kraepelin divided dementia praecox into three sub-

types: hebephrenic, catatonic, and paranoid. In the case-historical records of the

nineteenth century there is little indication of paranoid patterns of behavior among

patients diagnosed as hysterical; but the hebephrenic and catatonic forms of the dis-

ease have clear clinical parallels with hysteria. Kraepelin's hebephrenic state is char-

acterized by "various hyperesthesias," exaggerated sexual behaviors, and "expansive

mood shifts" including "uncontrollable laughing and sobbing." Catatonic dementia

praecox is marked by sensory, especially auditory, hallucinations, "great suscepti-

bility to suggestion," "impulsive actions," "religious delusions," and stereotyped

movements, mannerisms, and postures. At one point Kraepelin stated, with dubious

precision, that according to his data 18 percent of all cases of dementia praecox

involve hysteriform or apoplectiform attacks. These attacks, he added, occur twice

as frequently in female patients as in males. During the early twentieth century sev-

eral medical authors, two formerly Kraepelin's students, explored the diagnostic con-

tinuum between the older and newer syndromes.36

What scholars today can perceive only as rough descriptive congruences were for

some clinicians clearly overlapping medical conditions. In 1904 Charles Dana, the

noted New York neurologist, wrote a piece in the Boston Medical and Surgical Jour-