Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Empathy and Childhood Maltreatment: A Mixed-Methods Investigation

Uploaded by

aditya chaudharyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Empathy and Childhood Maltreatment: A Mixed-Methods Investigation

Uploaded by

aditya chaudharyCopyright:

Available Formats

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY 2014;26(2):97-110 RESEARCH ARTICLE

Empathy and childhood maltreatment:

A mixed-methods investigation

Simon C. Locher, B.SocSci. (Hons) BACKGROUND: Impaired empathy is regarded as a psychological conse-

Lisa Barenblatt, B.SocSci. (Hons)

quence of childhood maltreatment, yet few studies have explored this rela-

Department of Psychology tionship empirically. We investigated whether empathy differed in healthy

University of Cape Town

and maltreated individuals by examining their emotional responses to

Cape Town, South Africa

people in distress.

Melike M. Fourie, PhD

Department of Psychology

University of the Free State METHODS: Forty-nine individuals (age 20 to 60) viewed short film clips

Bloemfontein, South Africa from the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission testimonies

Dan J. Stein, MD, PhD depicting dialogues between victims and perpetrators of gross human

Department of Psychiatry rights violations. Participants were divided into 3 groups based on their

University of Cape Town

scores on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: control (n = 18), moder-

Cape Town, South Africa

ate maltreatment (n = 21), and severe maltreatment (n = 10). We employed

Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, PhD

a mixed-methods design to explore empathic responses to film clips both

Department of Psychology

University of the Free State quantitatively and qualitatively.

Bloemfontein, South Africa

RESULTS: Quantitative results indicated that self-reported empathy was

lower in the moderate maltreatment group compared to the control group,

but of similar strengths in the severe maltreatment and control groups.

However, qualitative thematic analysis indicated that both maltreatment

groups displayed themes of impaired empathy.

CONCLUSIONS: Our results support the notion that childhood maltreat-

ment is associated with impaired empathy, and suggest that such impair-

CORRESPONDENCE ment may differ depending on the level of maltreatment: moderate

Melike M. Fourie, PhD maltreatment was associated with emotional blunting and impaired cog-

Department of Psychology nitive empathy, whereas severe maltreatment was associated with emo-

University of the Free State

tional over-arousal and diminished cognitive insight.

Bloemfontein, South Africa, 9301

E-MAIL

KEYWORDS: empathy, child maltreatment, emotion regulation, attachment

marethem@gmail.com

AACP.com Annals of Clinical Psychiatry | Vol. 26 No. 2 | May 2014 97

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EMPATHY AND CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

I N T RO D U C T I O N salient, which in turn may trigger empathic concern and

cognitive empathy to imagine how the other feels.20

Early family relations are arguably the most important, Although some subcomponents of empathy,

and most enduring social relationships that affect a child’s like emotion matching, are present from birth, more

development,1 yet millions of children across the world are mature forms of cognitive empathy, like the capacity

exposed to negative early interactions, including maltreat- for mentalization, develop later in childhood and ado-

ment.2,3 Although the prevalence of childhood maltreat- lescence.21 The capacity to mentalize, or reflectively

ment is high across the world, it is particularly prevalent engage with another’s thoughts and feelings, is an abil-

in South Africa.4 ity that is rooted in the child’s early attachment expe-

Childhood maltreatment is associated with a vari- riences with parents.22,23 Empathic parents have the

ety of adverse psychological effects among adults,5 one capacity to observe the child’s mind, to understand and

reason being that maltreated children often grow up in contain their mental state, and to view the child as an

an environment that fails to provide appropriate oppor- intentional being, which promotes the child’s under-

tunities that guide development.6,7 A psychological abil- standing of minds.24-26

ity that has been implicated consistently in descriptions

of impairments due to maltreatment, is empathy.1,8,9 Child maltreatment and empathic

Notably, maltreated children tend to have difficulty shar- development

ing with, caring for, or taking the perspectives of oth- Although impaired empathy is cited commonly in the

ers.10 Moreover, maltreating parents often have impaired literature as a consequence of child maltreatment,27-29

empathy themselves.11 we found little empirical evidence that directly inves-

Impaired empathy is a trait impacting most important tigated this relationship. Most of the existing literature

relationships, and one that may be modified by therapy. is theoretical in nature, in which the fields of social

Understanding the role that maltreatment contributes to and developmental psychology,1,21 as well as neurosci-

the development of impaired empathy is critically impor- ence,22 describe conceptual models that explore the role

tant, and has significant clinical implications. In fact, vari- of maltreatment in contributing to the development of

ous clinical disorders with childhood maltreatment as a impaired empathy. Often these theories are based on

major etiological factor have impaired empathy as a core observations from clinical and case studies only.

symptom (eg, Cluster B personality disorders and complex Substantial indirect evidence points to a link

posttraumatic stress disorder).12,13 between maltreatment and empathy, however. In par-

ticular, many of the factors considered necessary for

Empathy the development of empathy are impaired in children

Empathy has been defined as the capacity to experience who experience maltreatment. For example, maltreated

and understand another’s emotional state in a manner children frequently 1) have insecure attachments with

that is congruent with the other person’s emotions.14,15 A their caregivers22; 2) develop negative internal working

long-standing tradition in psychology divides empathy models30; 3) are hypersensitive to emotional signals31;

into 2 components: affective and cognitive.16 The affec- and 4) have impaired emotion regulation.32 In the fol-

tive component constitutes the sharing of another per- lowing section, we explore these 4 lines of evidence that

son’s emotions via internal sensory representations of link maltreatment to impaired empathy.

their emotions. Based on a widely accepted framework, The ability to empathize is nurtured from infancy,

Bateson and Ahmad17 divide affective empathy into: starting with positive attachment experiences with

1) emotion matching, which is the phenomenon where caregivers.22 Empathic parenting associated with secure

one mirrors the emotional state displayed by another; attachment encourages the child to explore the parent’s

and 2) empathic concern, which is essentially sympathy. mind, which in turn encourages the development of the

The cognitive component of empathy reflects the ability capacity to mentalize.1 By contrast, child maltreatment

to infer and understand the mental state of another.18,19 typically leads to insecure attachment styles, which are

These subcomponents of empathy are partially distinct, associated with impaired empathy.22,30,33 Moreover, mal-

but also highly interconnected. For example, emotion treated children with insecure attachments typically

matching may make the suffering of the other more internalize negative working models. For example, they

98 May 2014 | Vol. 26 No. 2 | Annals of Clinical Psychiatry

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

view themselves as inadequate and unlovable; see oth- light of the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized

ers as hostile and uncaring; and regard interpersonal that significant child maltreatment would be associated

interactions as potentially dangerous and painful.34 with impaired empathy, and that the severity of maltreat-

Because these negative internal working models are ment would be related linearly to the degree of impaired

likely to foster disdain, fear, and mistrust of others, they empathic responding.

undermine the development of empathy.35,36

Because maltreated children often are faced with

continual fear, they also frequently become hypersen- METHODS

sitive to negative emotional signals.31 As a result, mal-

treated children often experience intense emotional Participants

distress (devoid of sympathy) when faced with another’s Forty-nine racially diverse participants (White: 25, Black:

emotional distress.35,37,38 For example, one study showed 12, Colored (people of mixed race): 12; 33 women)

that maltreated children often became intensely dis- between the ages of 20 and 60 participated in the study.

tressed in the presence of another child crying in a play- To increase the generalizability of our findings, we sourced

ground.39 Instead of soothing or helping the other child, participants from the university campus and the local envi-

the maltreated children reacted with a combination of ronment through posters and an advertisement placed in

fear, anger, and violence. Such forms of emotional dis- a local newspaper. We thus made use of non-probability

tress hinder empathy because they foster a self-directed convenience sampling, and included all participants who

focus that detracts from the suffering of others.15 responded to our study advertisement.

Another factor necessary for the development of All participants completed the procedures described

empathy is emotion regulation.40 Cummings32 identi- below and received 90 ZAR (approximately 10 USD) as

fied 3 distinct patterns of emotion regulation in chil- gratuity. The study protocol was approved by the Research

dren when viewing another person in distress. These Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT)

are 1) adaptively concerned emotion regulation, which Department of Psychology.

is associated with moderate levels of negative affect that

are well modulated, together with empathy; 2) under- Experimental design and setting

controlled/ambivalent emotion regulation, which is We utilized a mixed methods research design that incor-

associated with underregulation of emotional behavior, porated both quantitative and qualitative data analysis.

high reactivity, and prolonged elevation of both positive This methodology enabled us to obtain rich, subjective

and negative affect; and 3) overcontrolled/unresponsive data indicative of participants’ experiences, in addition

emotion regulation, which is associated with low emo- to numerical measures of empathy and related emotions

tional and behavioral reactivity, and the inhibition of amenable to statistical analysis. Specifically, we used a

signs of distress. Maltreated individuals typically exhibit within-subjects mixed-model design, where stages of data

the latter 2 patterns, which are associated with signifi- collection took place sequentially. The study took place in

cant impairments in empathy.40 a laboratory at UCT’s Department of Psychology.

Study overview Stimuli

In the present investigation, we used the context of the Empathy-eliciting stimuli were film clips taken from a

South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) short documentary (A Long Night's Journey into Day,

hearings to elicit current and ecologically valid empathic Iris Films; 2000) depicting different encounters between

responses in participants. The TRC was established after victims and perpetrators who testified at the TRC public

apartheid with the purpose of engaging with and healing hearings. The hearings were of a case in which 7 young

the injustices of the past, mainly through exploring testi- men from the Gugulethu Township in Cape Town were

monial narratives of perpetrators and victims. killed. The amnesty applicants were a white police offi-

We used short, emotionally arousing clips from cer, Captain Bellingan (the commander of the opera-

the TRC hearings to explore empirically the relation- tion), and a black police collaborator, Mr. Mbelo. They

ship between varying degrees of child maltreatment and divulge 2 very different stories about their involvement

empathic responding in an adult participant sample. In in the killings.

AACP.com Annals of Clinical Psychiatry | Vol. 26 No. 2 | May 2014 99

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EMPATHY AND CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

The TRC uncovered the following details: The black specificity in nonclinical samples,42 and also shows high

officer, Mbelo, was sent to Cape Town to infiltrate a group test-retest reliability (.66 to .94) and internal consistency

of young men and train them under the pretext that they with alphas ranging between .70 and .93.43

were going to become soldiers of the anti-apartheid strug- Participants were divided into 3 groups based

gle. He then lured them into a trap where a team of police- on their total CTQ-SF scores. The control group had

men, including Captain Bellingan, were waiting to kill scores <36, which indicated no maltreatment or mild-

them. The press characterized the operation as a huge suc- moderate maltreatment on 1 subscale. The moderate

cess of the apartheid campaign against terrorists. During maltreatment group had scores between 36 and 54,

the TRC hearings of Bellingan and Mbelo’s amnesty appli- which indicated mild-moderate and moderate-severe

cation, the mothers of the 7 victims heard the horrifying maltreatment on multiple subscales. Finally, the severe

truth about what happened to their sons for the first time. maltreatment group had scores >55, which indicated

The clips for our study were taken from scenes of this moderate-severe and severe-extreme maltreatment on

hearing, as well as from a meeting between the moth- multiple scales.

ers and the black officer (Mbelo). During this meeting,

Mbelo asked the mothers for forgiveness. The stimuli Procedure

consisted of 4 short clips (1 to 2 minutes each) and 1 On arrival, participants provided informed consent

long clip (12 minutes). The 4 short clips depicted: 1) a and received general instructions regarding the proce-

forgiving mother, 2) an unforgiving mother, 3) a mother dures. Each participant was seated in front of a 17-inch

in distress (sobbing), and 4) an unrepentant perpetra- computer monitor and given headphones and answer

tor (Captain Bellingan). These 4 clips were contained booklets. To contextualize the clips, participants viewed

within the longer clip, which depicted the events of the a PowerPoint presentation providing information about

hearing in more detail, including the meeting between the specific TRC case they were about to watch. They

the victims’ mothers and the remorseful perpetrator. then viewed the 4 short clips (1 to 2 minutes each) and

completed the self-reported emotion scales after each

Measures clip. Clips were shown in 3 different random sequences

Self-reported emotion scales. Participants indicated their to avoid order effects. Finally, participants viewed the

current emotional state after viewing each of the 4 short longer (12 minutes) clip, and then completed the qualita-

clips by rating 4 emotional qualities (empathy, shame, tive questionnaire and the CTQ-SF. All participants were

anger, and sadness) on a 9-point Likert-type scale, rang- thoroughly debriefed after the study procedure and given

ing from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very strongly/extremely). the option to see a professional counsellor, if necessary.

Qualitative questionnaire. Participants completed

the qualitative questionnaire after they had viewed all Data analysis

the clips. It consisted of 13 open-ended questions that We analyzed each of the emotions rated on the quantita-

explored emotions and thoughts evoked by the foot- tive self-report scales using a 3 (group: control, moderate,

age. For example, participants were asked to describe: and severe maltreatment) × 4 (clip type: forgiving mother,

the overall feeling they experienced when watching the unforgiving mother, distressed mother, and unrepentant

film; personal memories that were triggered by the film; perpetrator) mixed factorial ANOVA. In instances where

and any emotional detachment they felt. the assumption of sphericity was violated, the degrees of

Childhood maltreatment. We used the Childhood freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser epsi-

Trauma Questionnaire Short-Form (CTQ-SF)41 to assess lon corrections. These correction factors are reported.

the severity of different types of child maltreatment. We also performed zero-order correlations between

CTQ-SF is a retrospective measure that consists of 25 participants’ total scores on the CTQ-SF and their mean

items that measure the frequency with which differ- emotion ratings for each emotion. These mean emotion

ent events took place when participants “were growing ratings were calculated by averaging the 4 emotion rat-

up”, ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). ings after each film clip for each emotion.

The CTQ-SF consists of 5 subscales: physical neglect, Two researchers (SCL and LB), who were blind to

emotional neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and maltreatment status, analyzed the qualitative data using

emotional abuse. The CTQ-SF has high sensitivity and thematic analysis in accordance with guidelines set out

100 May 2014 | Vol. 26 No. 2 | Annals of Clinical Psychiatry

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

by Braun and Clarke.44 Accordingly, patterns within the The mixed factorial ANOVA for empathy ratings

data were coded, and extracts from the data were collated detected a significant main effect for the type of clip,

into themes and subthemes. Themes were compared F (2.29, 103.08) = 106.73, P < .001, ηp2 = .70, ε = .76. Post-

against the data and further refined until they were inter- hoc contrasts indicated that empathy was significantly

nally consistent and distinctive, and offered a convincing higher following the distressed mother clip than the for-

representation of the data. In general, we approached the giving mother, the unforgiving mother, and the unrepen-

analysis in an inductive fashion. The themes empathy tant perpetrator clips (P values < .001, r coefficients > .60).

and impaired empathy were approached in a deductive Empathy following the unrepentant perpetrator clip was

fashion, however, based on the framework of empathy also significantly lower than the forgiving mother and the

suggested by Bateson and Ahmad.17 Our approach var- unforgiving mother clips (P values < .001, r coefficients

ied between a semantic one, where themes were formed > .84), while empathy responses following the latter 2 clips

from explicit or surface meanings of the data, and an did not differ.

interpretive one, where the context of statements was Empathy ratings also differed significantly between

taken into account.45 the study groups, F (2, 45) = 6.75, P = .003, ηp2 = .23.

To integrate the quantitative and qualitative data sets, Bonferroni post-hoc testing revealed that empathy ratings

we used a multi-stage data analysis process that has been for the moderate maltreatment group were significantly

suggested to be appropriate for mixed methods research.46 lower than that of the control group (P < .05, r = .41) and

Briefly, we quantified the qualitative data by summing the the severe maltreatment group (P < .01, r = .42). However,

number of occurrences of each theme in each participant empathy ratings did not differ significantly between the

and then divided this score by the number of participants control and severe maltreatment groups (P = 1.00, r = .09).

in each group. The frequency of each theme first was Finally, there was no significant interaction between group

rated independently by 2 researchers (SCL and LB), who and type of clip, (P = .17).

remained blinded to maltreatment status, and then aver- Because empathy was the main focus of our study,

aged to form the final score. The level of agreement between we summarize the results for sadness, shame, and

these researchers was >85%. The thematic frequency esti- anger briefly. Mixed factorial ANOVA results indicated

mates per group were then compared with the quantitative that these analyses were all significant for the main

results to determine similarities and differences between effect of type of clip (P values < .001). Post-hoc contrasts

the data sets. revealed that sadness was significantly higher following

the distressed mother clip than the other clips (P values

< .001, r coefficients > .60), and significantly lower fol-

R E S U LT S lowing the unrepentant perpetrator clip than the other

clips (P values < .001, r coefficients > .73). In terms of

Participants shame, participants’ ratings were significantly higher

Based on participants’ CTQ-SF scores, 18 were classified following the distressed mother clip than the other

as having experienced no, or mild levels, of maltreat- three clips (P values < .01, r coefficients > .44). Finally,

ment (control group), 21 were classified as having expe- ratings of anger were significantly higher following the

rienced moderate levels of maltreatment (moderate distressed mother clip than all the other clips (P val-

maltreatment group), and 10 were classified as having ues < .05, r coefficients > .36). Anger was also signifi-

experienced severe levels of maltreatment (severe mal- cantly higher following the unremorseful perpetrator

treatment group). Chi-square analyses indicated that clip than following the forgiving mother clip (P < .001,

these study groups did not differ significantly in terms r = .63), and significantly higher following the unforgiv-

of the distribution of age, sex, or racial representation ing mother clip than following the forgiving mother clip

(P values > .39) (P < .001, r = .62).

In terms of group effects, ratings of shame differed

Quantitative results significantly between the study groups, F (2, 41) = 5.17,

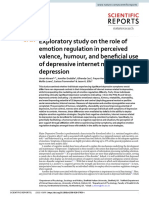

Emotion ratings in response to the TRC clips. FIGURE P = .01, ηp2 = .20, with significantly higher ratings of

illustrates subjective emotion ratings obtained after shame for the severe maltreatment group than for the

each short clip. control group (P < .05, r = .39) and the moderate mal-

AACP.com Annals of Clinical Psychiatry | Vol. 26 No. 2 | May 2014 101

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EMPATHY AND CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

FIGURE

Mean ratings for (A) empathy, (B) sadness, (C) anger, and (D) shame for the control, moderate

maltreatment, and severe maltreatment groups in response to each clip. Error bars represent

standard errors

A Empathy B Sadness

9 Control 9

8 Moderate 8

Intensity rating (1-9)

Intensity rating (1-9)

7 Severe 7

6 6

5 5

4 4

3 3

2 2

1 1

Forgive+ Forgive- Distress+ Repent- Forgive+ Forgive- Distress+ Repent-

C Anger D Shame

9 9

8 8

Intensity rating (1-9)

Intensity rating (1-9)

7 7

6 6

5 5

4 4

3 3

2 2

-3

1 1

Forgive+ Forgive- Distress+ Repent- Forgive+ Forgive- Distress+ Repent-

Film clip Film clip

Forgive+: forgiving mother, Forgive- : unforgiving mother, Distress+: mother in distress, Repent-: unrepentant perpetrator.

treatment group (P = .01, r = .43). The main effects of (P < .05; r = .33) as well as anger (P < .05; r = .26). Ratings

group did not reach significance for sadness, (P = .07, ηp2 of empathy and sadness did not correlate significantly

= .12), or anger, (P = .08, ηp2 = .11). with CTQ-SF scores.

Associations between maltreatment and elicited

emotions. TABLE 1 shows the mean self-reported emo- Qualitative results

tion-ratings for each emotion in each study group when Thematic analysis. We identified 7 themes (which are

ratings for all 4 clips were averaged. This table shows a italicized) from our analysis of the qualitative data, which

general trend, such that mean emotion ratings for all differed markedly between groups. The themes empa-

measured emotions were highest in the severe maltreat- thy, positive world view, and emotional awareness were

ment group, whereas they were lowest in the moderate more common in the control group, whereas the themes

maltreatment group. impaired empathy, malignant world view, and poor emo-

To explore further the relationship between sub- tional awareness, were more common in the 2 maltreat-

jective emotion ratings and the degree of maltreat- ment groups. The theme emotional distress was infrequent

ment, we performed zero-order correlations between in the control and moderate maltreatment groups, but was

total scores on the CTQ-SF and mean emotion ratings expressed commonly in the severe maltreatment group.

across all groups. Significant positive correlations were Because empathy is the focus of this study, we discuss

detected between CTQ-SF scores and ratings of shame the themes empathy and impaired empathy in detail. The

102 May 2014 | Vol. 26 No. 2 | Annals of Clinical Psychiatry

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

TABLE 1

Mean self-reported emotion ratings from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much) for each study group

Moderate Severe

Control maltreatment maltreatment

Emotion

(n = 18) (n = 21) (n = 10)

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

Empathy 5.94 (1.16) 4.69 (1.48) 6.25 (1.05)

Sadness 5.74 (1.25) 4.99 (1.56) 6.15 (0.98)

Anger 4.82 (1.96) 4.40 (1.95) 6.08 (1.50)

Shame 3.53 (1.88) 3.32 (1.73) 5.53 (1.89)

Means represent the mean self-reported emotion rating for each group across all 4 film clips.

other themes and subthemes are summarized in TABLE 2 “Seeing Mbelo’s face in response to the unfor-

(see TABLE 3 for examples of quotes from each theme). giving mother. I felt deeply sorry for him as his

THEME 1: EMPATHY. Participants who displayed highly expression was accepting of anything that the

empathic responses (mostly those in the control group) mothers may say.”

tended to have numerous examples of each empathy sub- THEME 2: IMPAIRED EMPATHY. This theme was marked

theme, which illustrates how the component processes of by responses that revealed a lack of empathy, including

empathy combine in highly empathic responses. statements showing difficulty understanding the mental

Participants demonstrated the subtheme imagine-self states of others. We observed impaired empathy most

perspective when they imagined how they would feel if they frequently in the responses of the maltreatment groups.

were in the position of 1 of the people portrayed in the TRC The subtheme poor understanding of others’ mental

footage. For example, 1 participant stated: states reflects an impairment of the imagine-other per-

“I absolutely understood her need to know [the spective. For example, in response to a scene showing

mother, who was asking Mbelo why he killed one of the mothers crying out in pain after viewing foot-

her son]. In the face of such brutality, you have age of her dead son, 1 participant in the moderate mal-

to know, especially if it is your loved one… I treatment group wrote:

could relate.” “I felt detached from the mother who screamed/

Similarly, the imagine-other perspective reflects the performed in front of all the people. One doesn’t

ability to imagine how another thinks or feels given their have to ‘perform’ to show one’s grief. I keep it

situation. In relation to the scene where Mbelo appealed to inside.”

the mothers for forgiveness, 1 participant stated: Some participants demonstrated an absence of emo-

“I perceived [Mbelo] differently in that context tional contagion in statements showing emotional blunting

with the mothers. I perceived him to be truly and difficulty feeling emotions in response to others’ pain.

remorseful. I was heartened by his genuineness, For example, when asked to describe “your overall feeling

the fact that he took responsibility.” after watching the film” a participant in the moderate mal-

Emotional contagion (“emotion catching”) could treatment group stated:

be described as instances in which an individual “[I felt] very little as I’m not someone who expe-

feels the same emotion that they observe in another. riences emotions easily. I felt a little sad but

For example: that’s all.”

“The despair of the mothers was heart-breaking, I Absence of sympathy was shown by remarks indicating

cried uncontrollably, I empathized.” a lack of concern for others’ pain.

Finally, the subtheme empathic concern/sympathy Finally, we observed extreme impairments in empathy

was detected in statements that demonstrated sympathy in bizarre misattributions, where the participant displayed

and compassion toward the protagonists of the film foot- strange misattributions of emotions, as in this example

age, for example: from a participant in the severe maltreatment group:

AACP.com Annals of Clinical Psychiatry | Vol. 26 No. 2 | May 2014 103

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EMPATHY AND CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

TABLE 2

Summary of themes and subthemes from the qualitative thematic analysis

Theme Subthemes

1. Empathy Imagine-self perspective; imagine-other perspective; emotional contagion; empathic concern/sympathy

2. Impaired empathy Poor understanding of others’ mental states; absence of emotional contagion; absence of sympathy;

bizarre attribution of another’s behavior

3. Positive world view Positive attitude towards forgiveness; faith in goodness of humanity; sense that life has meaning

4. Malignant world view Despair; absence of hope; distrust towards others; attitude that perpetrators are inherently evil

5. Emotional distress Intense feelings of anger and hatred; fear and horror; guilt and shame; triggering of traumatic memories;

somatic distress

6. Emotional awareness Focus on emotional signals; rich and complex understanding of others’ emotions; proficiency in

understanding personal emotions

7. Poor emotional Poor understanding of emotions in self and others; emotional blunting; avoidance tendencies

awareness

“I felt anger when Mbelo was talking about staying frequencies of the emotional distress theme, and also

drunk to mask pain. [It was] as though he was hav- had significantly higher ratings of shame (and to a lesser

ing a good time forgetting.” extent anger) than the other 2 groups on the quantitative

The footage the participant referred to, in fact, emotion scales. This pattern of increased emotional dis-

showed a guilt-stricken Mbelo explaining how he drank tress in the severe maltreatment group was corroborated

as a form of escapism to forget the (unacceptable) actions by the significant positive correlations between ratings of

that he had committed. shame and anger, and total CTQ-SF scores. Thus greater

levels of maltreatment were associated with higher rat-

Links between qualitative and quantitative ings of shame and anger in general.

results

TABLE 4 presents the quantification of themes across the

study groups. We combined the quantified qualitative DISCUSSION

results with the quantitative results in order to detect a

pattern that differentiated between the 3 study groups. In this study, we examined the relationship between

We found that the qualitative data overlapped clearly child maltreatment and empathy in a cohort of adult

with the quantitative data, yet we also observed some individuals. Participants were divided into 3 study

significant differences between the 2 sets of data. We groups based on their scores on the CTQ-SF: 1) control

describe the most important similarities and differ- (little to no maltreatment), 2) moderate maltreatment,

ences below. and 3) severe maltreatment. Consistent with our pre-

With regard to empathy, the control group displayed dictions, the control group displayed high empathy on

higher levels than the moderate maltreatment group both the quantitative and qualitative measures, and the

across both data sets. However, for the severe maltreatment moderate maltreatment group displayed low levels of

group, empathic responses differed markedly; whereas the empathy on both measures. However, we did not expect

thematic analysis indicated that this group had the lowest to see the results we observed in the severe maltreat-

ratings for empathy and the highest for impaired empathy, ment group. This group displayed low levels of empathy

their quantitative empathy ratings were high (similar to that on the qualitative measure, but high levels of empathy

of the control group). on the quantitative measure. We contend that distinct

In terms of emotional distress, both data sets indi- patterns of empathic responding in the 2 maltreatment

cated that the control and moderate maltreatment groups groups may have resulted from differences in factors

experienced relatively low levels of emotional distress. such as emotion regulation, attachment, and emotional

However, the severe maltreatment group displayed high avoidance.

104 May 2014 | Vol. 26 No. 2 | Annals of Clinical Psychiatry

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

TABLE 3

Examples of quotes for each theme and subtheme, and relation to maltreatment status

Theme Subtheme Quotes

Empathy Imagine-self perspective “I absolutely understood her need to know [the mother, who was asking Mbelo why

he killed her son]. In the face of such brutality, you have to know, especially if it is your

loved one… I could relate.”a

Imagine-other perspective “I perceived [Mbelo] differently in that context with the mothers. I perceived him

to be truly remorseful. I was heartened by his genuineness, the fact that he took

responsibility.”a

Emotional contagion “The despair of the mothers was heart-breaking, I cried uncontrollably, I empathized.”a

Empathic concern “Seeing Mbelo’s face in response to the unforgiving mother. I felt deeply sorry for him

as his expression was accepting of anything that the mothers may say.”a

Impaired Poor understanding of others’ “I felt detached from the mother who screamed/performed in front of all the people.

empathy mental states One doesn’t have to ‘perform’ to show one’s grief. I keep it inside.”b

Absence of emotional “[I felt] very little as I’m not someone who experiences emotions easily. I felt a little sad

contagion but that’s all.”b

Absence of sympathy “I didn’t feel any pain personally…”b

Bizarre misattributions “I felt anger when Mbelo was talking about staying drunk to mask pain. [It was] as

though he was having a good time forgetting.”c

Positive world Positive attitude towards “[When the] mother offered forgiveness—I was amazed. I felt a sense of healing and

view forgiveness an ability to move forward. Her wisdom and character made me feel she had done the

right thing.”a

Faith in the goodness “I keep on being in awe with us humans, [with our] inner power and strength.”a

of humanity

Malignant Absence of hope “[My past experiences] made me think that people can and will do anything to each

world view other and sometimes there’s nothing to do but be in pain.”c

Despair “I feel guilt, shame, and defeat for my situation and those on the video. Pity. Pity. Pity.”b

Distrust of others, attitude “I would scream and run away from them [the perpetrators] in fear. They have killed

that all perpetrators are before and will again. Something is mentally wrong with them.”c

inherently evil

Emotional Intense feelings of fear and “Seeing the footage was heart-stopping… My brain was pounding, my breathing was

distress horror heavier.”c

Guilt and shame “I am feeling the guilt and shame that Bellingan and Mbelo should be feeling.”c

Extreme somatic distress “I experienced… chills down my spine, felt as if my hair was being electrocuted….”c

Emotional Focus on emotional signals “I was desperately searching [Bellingan] for any hint of emotion or remorse, but I never

awareness found it.”a

Rich and complex “I felt her [the unforgiving mother] battle was the hardest as she was in conflict between

understanding of others’ how she truly felt and what a transcendent moral code demanded of her.”a

emotions

Proficiency in understanding “[My detachment from the mother in distress] was related not to the events unfolding in

personal emotions the court but rather my own issues.”a

Poor Poor understanding of “[I felt] no guilt or shame – [I was] not there at the time.”b

emotional emotions in self and others “…Mbelo described smilingly how it was just another day on the job” [referring to a

awareness scene where Mbelo was clearly ashamed].b

Emotional blunting “I feel a little detached because it hasn’t affected me personally.”b

“I find it difficult to love and sometimes I can’t [feel] sorry for other people.”b

a Control group.

bModerate maltreatment group.

cSevere maltreatment group.

AACP.com Annals of Clinical Psychiatry | Vol. 26 No. 2 | May 2014 105

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EMPATHY AND CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

TABLE 4

Frequencies of themes in each study group

Association Moderate Severe

with empathy Theme Control maltreatment maltreatment

Positive Empathy +++ ++ +

Positive world view +++ ++ ++

Emotional awareness +++ ++ +

Negative Impaired empathy + ++ +++

Emotional distress ++ + ++++

Malignant world view + ++ +++

Poor emotional awareness + +++ ++++

Frequencies were determined by calculating the mean number of occurrences of each theme in each group: + very infrequent; ++ infrequent; +++ frequent; ++++ very frequent.

Empathic responses in the maltreatment In contrast to the severe maltreatment group, par-

groups ticipants in the moderate maltreatment group displayed

In terms of the quantitative emotion data, the severe impairments in empathy across both the qualitative

maltreatment group displayed significantly higher and quantitative data sets. In particular, the moderate

empathy than the moderate maltreatment group. maltreatment group showed significantly lower empa-

However, they also displayed high levels of anger and thy ratings than the other 2 groups. They also displayed

sadness, and significantly higher levels of shame than low empathy and high impaired empathy themes, and

both the moderate maltreatment and control groups. often displayed poor understanding of others’ mental

These elevated levels of negative affect could be argued states, possibly reflecting poor cognitive empathy. The

to reflect increased emotional distress. Our qualitative moderate maltreatment group had very low levels of the

thematic analysis supported this interpretation, show- theme emotional distress, and did not have high ratings

ing that the severe maltreatment group had the high- of shame, anger, or sadness (as seen in the severe mal-

est ratings of the theme emotional distress. The single treatment group). Therefore, the moderately maltreated

self-rating of empathy we employed may therefore group displayed blunted affect as well as impairments in

not have been as specific to empathy as we intended, both affective and cognitive empathy.

and also may have been influenced by feelings of We found it intriguing that the moderate and severe

emotional distress. maltreatment groups showed such contrasting affective

The elicitation of an isomorphic emotional responses, yet both groups displayed impaired cognitive

response to that observed in another is an integral com- empathy and sympathy. Below, we first consider how

ponent of affective empathy, termed emotion match- these different affective response patterns could poten-

ing.47 But an empathic response also involves sympathy tially inhibit empathic responding. We then explore

and cognitive empathy.17 Our qualitative results indi- the potential mechanisms that may underlie these pat-

cated that the severe maltreatment group was charac- terns. Finally, we describe factors that may contribute

terized by extraordinary affective responses to the clips, to impaired empathy that may be common across both

indicative of emotional over-arousal or distress, but also maltreatment groups.

by low levels of cognitive empathy and sympathy (ie,

low ratings for empathy and emotional awareness, and Patterns of affective responding

high ratings for impaired empathy and poor emotional and impaired empathy

awareness). The severe maltreatment group’s data thus When an individual matches the emotion they observe in

suggest a pattern of decreased cognitive empathy and another in a well-modulated manner, it is likely that this

sympathy, in addition to increased emotion contagion. emotion matching will act as a trigger for cognitive empa-

106 May 2014 | Vol. 26 No. 2 | Annals of Clinical Psychiatry

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

thy and sympathy.17 We detected this “ideal” response ened to the undercontrolled emotion regulation pattern

frequently in the qualitative responses of our control described by Cummings.32

group: participants’ moderate distress in response to Attachment styles. Insecure attachment styles

the footage appeared to trigger both sympathy and an are present in the majority of maltreated individuals,

attempt to understand the other’s mental state (ie, cogni- and also have been linked to impaired empathy.30,48

tive empathy). Although we did not measure attachment directly in the

In contrast to the control group, we observed present study, we offer some interpretations here about

blunted affect in response to the empathy-eliciting stim- the nature of attachment styles in our 2 maltreatment

uli for the moderate maltreatment group. Blunting and/ groups based on previous research and speculation.

or avoidance is likely to prevent the affective synchrony An avoidant attachment style is associated with

that may develop when an individual is exposed to blunted affect, and a tendency toward being emotion-

another’s distress, because blunting removes the emo- ally distant from others.49 This affective pattern resem-

tional stimulus that triggers an empathic response.14,22 It bles the blunted affect we observed for participants in

is not surprising therefore that participants in the mod- our moderate maltreatment group. By contrast, the anx-

erate maltreatment group showed little sympathy and ious and disorganized attachment styles are associated

cognitive empathy. with elevated negative affect and unregulated (disorga-

Participants in the severe maltreatment group nized) emotional responses, respectively. Both of the

tended to display emotional distress in response to the latter affective patterns are consistent with the intense

footage, but with low levels of empathy and sympa- affect we observed in our severe maltreatment group.

thy. It has been proposed that uncontrollable distress Emotional avoidance. It is well documented that

in response to another’s suffering may overwhelm the maltreated individuals have a tendency to experience

individual to the extent that it detracts from the other’s intense, uncontrollable negative affect.31 However, vari-

experience of pain.15 Because intense distress is an ous authors also describe manifestations of emotional

uncomfortable sensation, it is likely to lead to a self- avoidance in maltreated individuals, including emo-

directed focus, which then undermines the salience of tional suppression,50 and avoidant coping strategies.51

the other person’s suffering. Decety and Lamm15 rightly Although intense emotionality and emotion avoid-

notes that, “in the case of empathy, the best response ance appear to be diametrically opposed, they may be

to another’s distress may not be distress, but efforts to related closely. For example, because distressing stimuli

soothe that distress.” Therefore the inability to regulate often elicit intense negative affect and feelings of shame

negative emotions in the severe maltreatment group in maltreated individuals,52 these individuals may be

may have prevented them from experiencing cognitive motivated to adopt an avoidant emotional stance. This

empathy and sympathy. behavior is consistent with our findings for the mod-

erate maltreatment group, but does not explain the

Potential mechanisms underlying impaired heightened distress observed for the severe maltreat-

empathy in maltreatment ment group.

Emotion regulation. Research has shown that the major- One possible explanation for the above discrepancy

ity of maltreated individuals have impaired emotion reg- is that, although distress may motivate avoidance in mal-

ulation,32,40 which has been linked to impaired empathy.14 treated individuals, some may be incapable of imple-

The behavioral patterns that are characteristic of the menting this defense. In particular, severely maltreated

forms of emotion regulation typically exhibited by mal- individuals may be unable to inhibit negative affect (even

treated individuals show considerable overlap with the when they are highly motivated to do so) because of

patterns of responses we observed in the present study. undercontrolled emotion regulation, anxious/disorga-

For example, the blunted emotionality and unempathic nized attachment, or the post-traumatic phenomenon of

responses of the moderate maltreatment group may be triggering, which is observed more readily following high

associated with the overcontrolled/unresponsive emo- levels of trauma.34

tion regulation pattern described by Cummings.32 By The tendency toward emotional avoidance in mal-

contrast, the intense, uncontrollable, and unempathic treated individuals also has conceptual overlap with

responses of the severe maltreatment group could be lik- Freud’s53 theory of repression. This defense mechanism

AACP.com Annals of Clinical Psychiatry | Vol. 26 No. 2 | May 2014 107

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EMPATHY AND CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

may remain intact in moderate maltreatment, but may empathic impairment differently.9 However, most of our

become overwhelmed with severe maltreatment, lead- participants had experienced >1 type of maltreatment; it

ing to overwhelming negative affect due to the emer- was thus impossible to group them according to type of

gence of disturbing unconscious material.54,55 maltreatment.

A fourth limitation was our use of a single, global,

Common features across the maltreatment self-rating for empathy, which may have been influenced

groups by emotional distress in some subjects. Our rationale for

Besides the differences highlighted above, participants in employing this measure was to save time, that is, we did

our maltreatment groups also may share features associ- not want measures of state affect between clips to detract

ated with impaired empathy. One such feature is impaired from participants’ emotional engagement with the foot-

mentalization, which has been linked to poor cognitive age. A more accurate way to assess empathic responding

empathy.56 Fonagy1 argued that maltreatment often results may be to include several adjectives describing different

in impaired mentalization because abusive or neglectful emotional states that load onto empathy and personal

parents typically fail to engage with the thoughts and feel- distress, respectively.64

ings of the child. The child’s internal experience therefore Finally, because we did not assess participants’

remains unlabeled and confusing, which, in turn, hinders attachment styles and emotion regulation patterns, some

the child from forming accurate representations of others’ of our conclusions may be speculative. Future research

mental states.57,58 may benefit from assessing the contribution of these

Another shared feature may be impaired sympathy, factors that potentially may mediate the relationship

which has been linked to maltreatment because abused between empathy and maltreatment.

children often internalize the unsympathetic behavior of

their parents.59,60 We observed a lack of sympathy in both

maltreatment groups, which may be linked to the theme CONCLUSIONS

malignant world view. For example, when a mother in the

footage forgave her son’s killer, she was described as weak; In this study, we found empirical evidence that child

when a mother cried, she was seen as “performing”; and maltreatment is associated with impaired empathy.

when a perpetrator begged for forgiveness, he was viewed Furthermore, our results suggest that such impairments

as a “cold-hearted liar.” manifest differently in moderately and severely maltreated

individuals. Specifically, moderately maltreated partici-

Limitations and directions for future research pants displayed blunted affect in response to the empa-

The current study contributed significantly to our under- thy-eliciting clips, which could result from overcontrolled

standing of impaired empathy as one of the enduring emotion regulation, avoidant attachment, or a proclivity

effects of child maltreatment. A number of methodologi- toward avoiding distressing psychological content. By con-

cal limitations should be noted, however. First, retro- trast, severely maltreated participants displayed intense,

spective methods of assessing child maltreatment have uncontrollable emotional distress in response to the clips,

important limitations61; corroborative evidence should which could result from lack of emotion regulation, anxious

thus be used whenever possible. Second, our relatively or disorganized attachment, or “unsuccessful” emotional

small sample size may have reduced the power of our avoidance.

analyses. Third, because of the exploratory nature of The findings of the present study, though exploratory

this study, we did not employ a randomized sampling in nature, may be of practical value in understanding psy-

method with groups matched for third variables that chopathology and informing current treatment programs.

may influence empathy (eg, age, sex, race, or develop- Our findings reinforce the notion that empathy training

mental timing and chronicity of maltreatment).19,62,63 It should form an integral component of treatment pro-

should be noted, however, that our groups did not dif- grams following maltreatment.65 In addition, the thera-

fer statistically in terms of age, sex, or race. We also did peutic process may benefit from a better understanding

not group participants according to the type of maltreat- of the nature of impaired empathy in maltreated indi-

ment they experienced, which may be a confounding viduals. For example, a vital component of psychother-

factor because different types of maltreatment may affect apy involves enabling patients to develop an awareness

108 May 2014 | Vol. 26 No. 2 | Annals of Clinical Psychiatry

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

of their own and others’ mental states, thereby finding DISCLOSURES: Mr. Locher, Ms. Barenblatt, Dr. Fourie, and

meaning in their behavior.1 The present study’s findings Dr. Gobodo-Madikizela report no financial relationship

may help therapists gain deeper insight into the differ- with any company whose products are mentioned in this

ent behavioral patterns associated with impaired empa- article or with manufactuers of competing products. Dr.

thy (eg, emotional overarousal or blunted affect), thereby Stein has received research grants and/or consultancy

enabling them to better assist patients in identifying prob- honoraria from AMBRF, Biocodex, Lundbeck, National

lematic patterns of cognition and behavior. Our research Responsible Gambling Foundation, Novartis, Servier, and

also suggests that, rather than using a single intervention, Sun.

empathy treatment programs may need to be tailored

according to the particular kind of empathic deficit. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: We thank Professor Mark Solms for

In sum, our study shows that child maltreat- editorial comments as well as for his conceptual input.

ment can have a significant impact on an individual’s This article was part of a 3-year research project (2009 to

empathic responding toward others. Because empathy 2012), "Empathy: Emotional responses to video-taped

plays such a vital role in social relations, it is important scenes from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

to explore further how maltreatment impairs empathy, of South Africa," funded by the Fetzer Institute and the

and how the burden of impaired empathy can be treated National Research Foundation.

or prevented. Our study has made important first steps Authors S.C. Locher and L. Barenblatt contributed

in exploring these complex relationships. ■ equally to this article.

REFERENCES

1. Fonagy P. Attachment and borderline personality 17. Bateson CD, Ahmad NY. Using empathy to improve 31. Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood

disorder. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2000;48:1129-1146. intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety dis-

2. Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment Policy Review. 2009;3:141-177. orders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry.

in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adoles- 18. Preston SD, de Waal FB. Empathy: its ultimate and 2001;49:1023-1039.

cent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118:933-942. proximate basis. Behav Brain Sci. 2002;25:1-20. 32. Cummings EM. Coping with background anger in

3. Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, et al. Burden and 19. Singer T. The neuronal basis and ontogeny of early childhood. Child Dev. 1987;58:976-984.

consequences of child maltreatment in high-income empathy and mind reading: review of literature and 33. Barnett D, Ganiban J, Cicchetti D. Maltreatment,

countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68-81. implications for future research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. negative expressivity, and the development of type D

4. Pierce L, Bozalek V. Child abuse in South Africa: an 2006;30:855-863. attachments from 12 to 24 months of age. In: Vondra

examination of how child abuse and neglect are defined. 20. Zahavi D. Simulation, projection and empathy. J, Barnett D, eds. Atypical attachment in infancy and

Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:817-832. Conscious Cogn. 2008;17:514-522. early childhood among children at developmental

5. Hart SN, Binggeli NJ, Brassard MR. Evidence of 21. Abu-Akel A. A neurobiological mapping of theory of risk. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing;

the effects of psychological maltreatment. Journal of mind. Brain Res Rev. 2003;43:29-40. 1999:97-118.

Emotional Abuse. 1997;1:27-58. 22. Watt D. Toward a neuroscience of empathy: 34. Herman JL. Complex PTSD: a syndrome in survi-

6. McCord J. A forty year perspective on effects of child integrating affective and cognitive perspectives. vors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J Trauma Stress.

abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 1983;7:265-270. Neuropsychoanalysis. 2007;9:119-172. 1992;5:377-391.

7. Watkins HD, Bradbard MR. Child maltreatment: an 23. Gobodo-Madikizela P. Trauma, forgiveness, and the 35. Briere J, Spinazzola J. Phenomenology and psy-

overview with suggestions for intervention and research. witnessing dance: Making public spaces intimate. J Anal chological assessment of complex posttraumatic states.

Family Relations. 1982;31:323-333. Psychol. 2008;53:169-188. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:401-412.

8. de Paul J, Guibert M. Empathy and child neglect: a 24. Fonagy P, Target M. Playing with reality: I. Theory of 36. Laub D, Auerhahn NC. Failed empathy: a cen-

theoretical model. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:1063-1071. mind and the normal development of psychic reality. Int tral theme in the survivor’s holocaust experience.

9. Feshbach N. The construct of empathy and the J Psychoanal. 1996;77:217-233. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 1989;6:377-400.

phenomenon of physical maltreatment of children. In: 25. Fonagy P, Target M. Attachment and reflective func- 37. Liotti G. Trauma, dissociation, and disorga-

Cicchetti D, Carlson V, eds. Child maltreatment: theory tion: their role in self-organization. Dev Psychopathol. nized attachment: Three strands of a single braid.

and research on the causes and consequences of child 1997;9:679-700. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training.

abuse and neglect. New York, NY: Columbia University 26. Target M, Fonagy P. Playing with reality II: the devel- 2004;41:472-486.

Press; 1989:349-373. opment of psychic reality from a theoretical perspective. 38. Thompson RA. Emotion and self-regulation. In:

10. Mash EJ, Wolfe DA. Abnormal child psychology. 4th Int J Psychoanal. 1996;77:459-479. Thompson RA, ed. Socioemotional Development.

ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing; 2010. 27. de la Vega A, de la Osa N, Ezpeleta L, et al. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1990:367-467.

11. Kaufman J, Zigler E. Do abused children become Differential effects of psychological maltreatment on 39. Klimes-Dougan B, Kistner J. Physically abused pre-

abusive parents? Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186-192. children of mothers exposed to intimate partner vio- schoolers’ responses to peers’ distress. Developmental

12. Gelder M, Mayou R, Cowen P. Shorter oxford text- lence. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35:524-531. Psychology. 1990;26:599-602.

book of psychiatry. 4th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: 28. Horwitz AV, Widom CS, McLaughlin J, et al. The 40. Maughan A, Cicchetti D. Impact of child maltreat-

Oxford University Press; 2005. impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental ment and inter adult violence on children’s emotion

13. Kaplan H, Sadock B. Synopsis of psychiatry. 7th ed. health: a prospective study. J Health Soc Behav. 2001; regulation abilities and socioemotional adjustment.

Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1994. 42:184-201. Child Dev. 2002;73:1525-1542.

14. Decety J. Dissecting the neural mechanisms medi- 29. Chaitin J, Steinberg S. “You should know better”: 41. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al.

ating empathy. Emotion Review. 2011;3:92-108. expressions of empathy and disregard among vic- Development and validation of a brief screening version

15. Decety J, Lamm C. Human empathy through the tims of massive social trauma. Journal of Aggression, of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse

lens of social neuroscience. ScientificWorldJournal. Maltreatment, and Trauma. 2008;17:197-226. Negl. 2003;27:169-190.

2006;6:1146-1163. 30. Yates TM. The developmental psychopathol- 42. Paivio SC, Cramer KM. Factor structure and reli-

16. Hein G, Singer T. I feel how you feel but not always: ogy of self-injurious behavior: Compensatory regula- ability of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a

the empathic brain and its modulation. Curr Opin tion in posttraumatic adaptation. Clin Psychol Rev. Canadian undergraduate student sample. Child Abuse

Neurobiol. 2008;18:153-158. 2004;24:35-74. Negl. 2004; 28:889-904.

AACP.com Annals of Clinical Psychiatry | Vol. 26 No. 2 | May 2014 109

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EMPATHY AND CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

43. Bernstein D, Fink L. Manual for the Childhood childhood abuse and experiential avoidance among of attachment status, psychiatric classification, and

Trauma Questionnaire. San Antonio, TX: The inner-city substance users: the role of emotional nonac- response to psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;

Psychological Corporation; 1998. ceptance. Behav Ther. 2007;38:256-268. 64:22-31.

44. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in 51. Thabet AA, Tischler V, Vostanis P. Maltreatment and 59. Widom CS. Does violence beget violence? A

psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. coping strategies among male adolescents living in the critical examination of the literature. Psychol Bull.

2006;3:77-101. Gaza Strip. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:77-91. 1989;106:3-28.

45. Willig C. Introducing qualitative research in psy- 52. Loader P. Such a shame – a consideration of shame 60. Wiehe VR. Approaching child abuse treatment from

chology: adventures in theory and method. Maidenhead, and shaming mechanisms in families. Child Abuse the perspective of empathy. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;

United Kingdom: Open University Press; 2005. Review. 1998;7:44-57. 21:1191-1204.

46. Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods 53. Freud S. Three essays on the theory of sexuality and 61. Maughan B, Rutter M. Retrospective reporting of

research: a research paradigm whose time has come. other works. vol 7. London, United Kingdom: Penguin childhood adversity: issues in assessing long-term recall.

Educational Researcher. 2004;33:14-26. Books; 1977. J Pers Disord. 1997;11:19-33.

47. Freedberg D, Gallese V. Motion, emotion and 54. Freud S. The standard edition of the complete psy- 62. Aber JL, Zigler E. Developmental considerations in

empathy in esthetic experience. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007; chological works of Sigmund Freud. Strachey J, trans-ed. the definition of child maltreatment. New Directions for

11:197-203. London, United Kingdom: Hogarth Press; 1986. Child and Adolescent Development. 1981;11:1-29.

48. Burnette JL, Davis DE, Green JD, et al. Insecure 55. Zepf S, Zepf F. Trauma and traumatic neurosis: 63. Mrazek PJ, Mrazek DA. Resilience in child maltreat-

attachment and depressive symptoms: the mediat- Freud’s concepts revisited. Int J Psychoanal. 2008; ment victims: a conceptual exploration. Child Abuse

ing role of rumination, empathy, and forgiveness. 89:331-353. Negl. 1987;11:357-366.

Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46:276-280. 56. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Psychotherapy for borderline 64. Batson CD, Early S, Salvarani G. Perspective taking:

49. Sandberg DA, Suess EA, Heaton JL. Attachment personality disorder: mentalization-based treatment. Imagining how another feels versus imagining how you

anxiety as a mediator of the relationship between Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2004. would feel. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

interpersonal trauma and posttraumatic symptomatol- 57. Alessandri SM. Mother-child interactional corre- 1997;23:751-758.

ogy among college women. J Interpers Violence. 2010; lates of maltreated and nonmaltreated children’s play 65. Hollingsworth J, Glass J, Heisler KW. Empathy

25:33-49. behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1992; deficits in siblings of severely scapegoated children: a

50. Gratz KL, Bornovalova MA, Delany-Brumsey A, et 4:257-270. conceptual model. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2007;

al. A laboratory-based study of the relationship between 58. Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, et al. The relation 7:69-88.

Do you wrestle with the

intractable and disabling

problems of your patients

with schizophrenia?

Then visit the Current Psychiatry

Schizophrenia & Other Psychotic

Disorders Resource Page

at CurrentPsychiatry.com

Here, find collected CURRENT PSYCHIATRY Pearls,

audiocasts, video interviews, and evidence-based review

articles—such as an approach to treating schizophrenia

prodrome by Vishal Madaan, MD, and colleagues.

Visit the Schizophrenia & Other Psychotic Disorders Resource page at:

www.currentpsychiatry.com/topics/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/landing.html

Providing psychiatrists with peer-reviewed, practical, and up-to-date advice

by leading authorities on common clinical challenges

110 May 2014 | Vol. 26 No. 2 | Annals of Clinical Psychiatry

You might also like

- Hunger: Mentalization-based Treatments for Eating DisordersFrom EverandHunger: Mentalization-based Treatments for Eating DisordersRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Child Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleDocument11 pagesChild Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleinsildaNo ratings yet

- Tully-Donohue2017 Article EmpathicResponsesToMotherSEmotDocument13 pagesTully-Donohue2017 Article EmpathicResponsesToMotherSEmotcecilia martinezNo ratings yet

- Harder - 2014Document5 pagesHarder - 2014Linda MkhizeNo ratings yet

- Development of Socio-Emotional Skills in BonobosDocument6 pagesDevelopment of Socio-Emotional Skills in BonobosplancheNo ratings yet

- Parental Attachment and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Adolescents: The Mediation Effect of Emotion RegulationDocument8 pagesParental Attachment and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Adolescents: The Mediation Effect of Emotion Regulationyo keraeziNo ratings yet

- The Neural Development of Empathy Is SensitiveDocument10 pagesThe Neural Development of Empathy Is SensitivebenqtenNo ratings yet

- The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Depression in Adolescents NeuropsikologiDocument9 pagesThe Cognitive Neuropsychology of Depression in Adolescents NeuropsikologiDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- Hessler 2010Document6 pagesHessler 2010Lisa VanesthaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Processing in Bullying - An Event-Related Potential StudyDocument8 pagesEmotional Processing in Bullying - An Event-Related Potential StudyTATIANA ALEXANDRA GALVIS ROMERONo ratings yet

- Does emotional abuse increase anxiety riskDocument5 pagesDoes emotional abuse increase anxiety riskshem nyangateNo ratings yet

- Akram 2021Document8 pagesAkram 2021Dafny C. AroneNo ratings yet

- La Competencia Emocional de Macarena Blázquez-Alonso, 1 Juan Manuel Moreno-Manso, 1 Ma. Elena García-Baamonde Sánchez, 1 Eloísa Guerrero-Barona1Document10 pagesLa Competencia Emocional de Macarena Blázquez-Alonso, 1 Juan Manuel Moreno-Manso, 1 Ma. Elena García-Baamonde Sánchez, 1 Eloísa Guerrero-Barona1Laura MartinezNo ratings yet

- Psikotik Pada AnakDocument8 pagesPsikotik Pada AnaknigoNo ratings yet

- ArticoleDocument8 pagesArticoleRuby FbkNo ratings yet

- Adelaide Attachment Mentalising Dec08Document55 pagesAdelaide Attachment Mentalising Dec08ssanagavNo ratings yet

- Bacon2018 Investigating The Association Between Fantasy Proneness and EmotionalDocument9 pagesBacon2018 Investigating The Association Between Fantasy Proneness and EmotionalDokajanNo ratings yet

- Mother-Infant Attachment Style As A Predictor of Depression Among Female StudentsDocument8 pagesMother-Infant Attachment Style As A Predictor of Depression Among Female Studentsdana03No ratings yet

- Sonkin Hamel 2019Document20 pagesSonkin Hamel 2019L BlincoeNo ratings yet

- Articol Anale - Tepordei, Panga - Dec 2016Document16 pagesArticol Anale - Tepordei, Panga - Dec 2016agapeanualexandraNo ratings yet

- Protocol RAHMA - FINAL1Document12 pagesProtocol RAHMA - FINAL1helalNo ratings yet

- Fonagy Template Applied Attachment and PD Paper For FOCUS Lorenzini and Fonagy FINAL 22febDocument40 pagesFonagy Template Applied Attachment and PD Paper For FOCUS Lorenzini and Fonagy FINAL 22febneacsu carmenNo ratings yet

- Fonagy Fonagy Et Al Mentalizing Group IJGP Fonagy Bateman V2Document29 pagesFonagy Fonagy Et Al Mentalizing Group IJGP Fonagy Bateman V2Tasos TravasarosNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0166432817303418 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0166432817303418 MainMustafa ŞekerNo ratings yet

- Attachment and PsyhopathologyDocument4 pagesAttachment and PsyhopathologySamueNo ratings yet

- Bidirectional Associations Between Parental Warmth, Callous Unemotional Behavior, and Behavior Problems in High-Risk PreschoolersDocument12 pagesBidirectional Associations Between Parental Warmth, Callous Unemotional Behavior, and Behavior Problems in High-Risk PreschoolerseaguirredNo ratings yet

- Predictors of eating disorder risk in anorexic adolescentsDocument17 pagesPredictors of eating disorder risk in anorexic adolescentsinnatullaini syachbellaaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Affective Disorders: Mengting Zhong, Xuechao Huang, E. Scott Huebner, Lili TianDocument7 pagesJournal of Affective Disorders: Mengting Zhong, Xuechao Huang, E. Scott Huebner, Lili TianTatiana padillaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Social Skills Training vs. Psychoeducation On Negative Attitudes of Mothers of Persons With Schizophrenia: A Pilot StudyDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Social Skills Training vs. Psychoeducation On Negative Attitudes of Mothers of Persons With Schizophrenia: A Pilot Studyedo_gusdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Behavioral SciencesDocument11 pagesBehavioral SciencesPuddingNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder A Case Study of An 11-Year-OldDocument67 pagesTreatment of Social Anxiety Disorder A Case Study of An 11-Year-OldSena UysakNo ratings yet

- Attachment Styles in Maltreated ChildrenDocument18 pagesAttachment Styles in Maltreated ChildrenAnonymous KrfJpXb4iNNo ratings yet

- 3 The Role of Parental Emotions in Parenting: Michael S. NystulDocument11 pages3 The Role of Parental Emotions in Parenting: Michael S. NystulPuan KameliaNo ratings yet

- How You Help A Child Go To Sleep Is Related To Their Behavioral Development, Finds New StudyDocument5 pagesHow You Help A Child Go To Sleep Is Related To Their Behavioral Development, Finds New StudyasddsaasdNo ratings yet

- The Early Development of Empathy: Self-Regulation and Individual Differences in The First Year 1Document14 pagesThe Early Development of Empathy: Self-Regulation and Individual Differences in The First Year 1Andreea Loredana CiobanuNo ratings yet

- CYP Case Study Assignment Virginia Toole 20260933 Dec 3, 2019 Part 2Document9 pagesCYP Case Study Assignment Virginia Toole 20260933 Dec 3, 2019 Part 2Ginny Viccy C TNo ratings yet

- Encopresis Happens - Geoff GoodmanDocument18 pagesEncopresis Happens - Geoff GoodmanMariana JaninNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory and Child AbuseDocument7 pagesAttachment Theory and Child AbuseAlan Challoner100% (3)

- Parental Validation and Invalidation Predict Adolescent Self-HarmDocument19 pagesParental Validation and Invalidation Predict Adolescent Self-HarmGaby BarrozoNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Psychosomatic Medicine: Developmental Contributions To Stress and DiseaseDocument12 pagesAttachment and Psychosomatic Medicine: Developmental Contributions To Stress and DiseaseJFFNo ratings yet

- Shame On Me - MurisDocument11 pagesShame On Me - MurisVíctor Chaves MuñozNo ratings yet

- Psychopathy and AttachmentDocument50 pagesPsychopathy and AttachmentErickson ArthurNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence and Social InteractionDocument51 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Social InteractionClaudia DaniliucNo ratings yet

- Childhood Trauma and Children's Emerging Psychotic Symptoms: A Genetically Sensitive Longitudinal Cohort StudyDocument8 pagesChildhood Trauma and Children's Emerging Psychotic Symptoms: A Genetically Sensitive Longitudinal Cohort StudyVikramjit KhangooraNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental HealthDocument10 pagesClinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental HealthAngeloNo ratings yet

- PSY 052 Module (Topic E)Document7 pagesPSY 052 Module (Topic E)derNo ratings yet

- Waller2014 PDFDocument23 pagesWaller2014 PDFsanggeethambigai vijayakumarNo ratings yet

- Psychopathology: Predisposing FactorsDocument12 pagesPsychopathology: Predisposing FactorsmarkyabresNo ratings yet

- Mutuality in Parent-Child Attachment TherapyDocument30 pagesMutuality in Parent-Child Attachment TherapyJulián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNo ratings yet

- The Basic Empathy Scale: A Chinese Validation of A Measure of Empathy in AdolescentsDocument12 pagesThe Basic Empathy Scale: A Chinese Validation of A Measure of Empathy in Adolescentsmya mewNo ratings yet

- From Emotional Abuse in Childhood To Psy PDFDocument24 pagesFrom Emotional Abuse in Childhood To Psy PDFNicoleta VasiliuNo ratings yet

- Promotion of Empathy and Prosocial Behaviour in CHDocument22 pagesPromotion of Empathy and Prosocial Behaviour in CHMira MiereNo ratings yet

- Child Maltreatment and Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Using The Childhood Trauma QuestionnaireDocument20 pagesChild Maltreatment and Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Using The Childhood Trauma QuestionnaireMarta PeartreesNo ratings yet

- ChildangerDocument26 pagesChildangerMarco RatioNo ratings yet

- 16-175Document9 pages16-175A dumb AroaceNo ratings yet

- MafaldaSilva Psicodrama ISPA 2021 PDFDocument11 pagesMafaldaSilva Psicodrama ISPA 2021 PDFmioluNo ratings yet

- Laterature Review: Running Head: Adolescent DepressionDocument9 pagesLaterature Review: Running Head: Adolescent Depressionapi-341424974No ratings yet

- Developmental PerspectiveDocument30 pagesDevelopmental PerspectivesikunaNo ratings yet

- Steele2010 PDFDocument7 pagesSteele2010 PDFDaniela StoicaNo ratings yet

- 30DayWM Call17 With Dr. Joe RubinoDocument35 pages30DayWM Call17 With Dr. Joe Rubinolisa252100% (1)

- NUML BS English Students Explore Animal CommunicationDocument4 pagesNUML BS English Students Explore Animal Communicationhabiba malikNo ratings yet

- Shape It! For Ecuador 2 Year and Unit PlansDocument89 pagesShape It! For Ecuador 2 Year and Unit PlansVkita MolinaNo ratings yet

- Langage Et Littérature-ImaginaireDocument524 pagesLangage Et Littérature-ImaginairejanaoseiNo ratings yet

- Topic - AIDocument20 pagesTopic - AIAG05 Caperiña, Marcy Joy T.No ratings yet

- Future Simple and Future ContinuousDocument9 pagesFuture Simple and Future ContinuousLeslie VazquezNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Fine Motor SkillsDocument94 pagesKindergarten Fine Motor SkillsVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Personal Development Quarter 1 Module 2 Developing The Whole PersonDocument25 pagesPersonal Development Quarter 1 Module 2 Developing The Whole PersonLove RazeNo ratings yet

- Epsy For Edpm Chapter 3,4 &5Document22 pagesEpsy For Edpm Chapter 3,4 &5mekit bekeleNo ratings yet

- PROFESSIONAL ETHICS (Bab 3PDF) PDFDocument45 pagesPROFESSIONAL ETHICS (Bab 3PDF) PDFMax LuxNo ratings yet

- How To Overcome Passive Aggressive Behavior 2Document3 pagesHow To Overcome Passive Aggressive Behavior 2cartered100% (2)

- Lesson Plan: Gwynedd-Mercy College School of Education Personal Integrity and Social ResponsibilityDocument9 pagesLesson Plan: Gwynedd-Mercy College School of Education Personal Integrity and Social Responsibilityapi-281554653No ratings yet

- Arbeitsblatt - Wechselpräpositionen 1Document3 pagesArbeitsblatt - Wechselpräpositionen 1Mohammed FaizanNo ratings yet

- Tecnology Humanities PDFDocument57 pagesTecnology Humanities PDFMaya ErnieNo ratings yet

- Kenny-230717-Google Data Scientist GuideDocument8 pagesKenny-230717-Google Data Scientist GuidevanjchaoNo ratings yet

- Piaget's Theory of LearningDocument24 pagesPiaget's Theory of LearningMuhammad Salman AhmedNo ratings yet

- EF4e Elem Filetest 10b Answer KeyDocument3 pagesEF4e Elem Filetest 10b Answer Key123456 78910No ratings yet

- Building and Establishing Harmonized Relationship With The Society or CommunityDocument32 pagesBuilding and Establishing Harmonized Relationship With The Society or CommunityJoshkorro GeronimoNo ratings yet

- D. C. Mathur Naturalistic Philosophies of Experience Studies in James, Dewey and Farber Against The Background of Husserls Phenomenology 1971Document169 pagesD. C. Mathur Naturalistic Philosophies of Experience Studies in James, Dewey and Farber Against The Background of Husserls Phenomenology 1971andressuareza88No ratings yet

- MORAL DEVELOPMENT EXAM REVIEWDocument1 pageMORAL DEVELOPMENT EXAM REVIEWAbigail N. DitanNo ratings yet

- Lý thuyết dịchDocument96 pagesLý thuyết dịchnguyenmaithanh100% (5)

- Calista RoyDocument16 pagesCalista RoyKyla A. CasidsidNo ratings yet

- Ebook Original PDF Delivering Authentic Arts Education 2Nd Australia All Chapter PDF Docx KindleDocument41 pagesEbook Original PDF Delivering Authentic Arts Education 2Nd Australia All Chapter PDF Docx Kindlewilma.carpenter644100% (24)

- John Hart Phrase Cue 5 Day Lesson Plans 1Document6 pagesJohn Hart Phrase Cue 5 Day Lesson Plans 1api-633531277No ratings yet

- Cops Method LessonDocument5 pagesCops Method Lessonapi-534206789No ratings yet

- The Use of Blogs in EFL TeachingDocument10 pagesThe Use of Blogs in EFL TeachingCarlosFerrysNo ratings yet

- Language Sciences: Joshua Nash, Peter MühlhäuslerDocument8 pagesLanguage Sciences: Joshua Nash, Peter MühlhäuslerPablo Andrés Contreras KallensNo ratings yet

- Second Language Acquisition HandoutsDocument10 pagesSecond Language Acquisition HandoutsmounaNo ratings yet