Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Activity - Comia - Russell Glenn S.

Uploaded by

Rochelle Marie Regencia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views3 pagesyes

Original Title

Activity_Comia_Russell Glenn S.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentyes

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views3 pagesActivity - Comia - Russell Glenn S.

Uploaded by

Rochelle Marie Regenciayes

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

RUSSELL GLENN S.

COMIA

BS INFO 3SMP1

ITST 304 - Principle of Systems Thinking

UNDERSTANDING THE SYSTEM – Systems thinking is the process of

understanding how things, regarded as systems, influence one another within

a whole. In nature, systems thinking examples include ecosystems in which

elements such as air, water, plants, and animals work together to survive or

perish.

Example: Some examples include transport systems; solar systems;

telephone systems; the Dewey Decimal System; weapons systems;

ecological systems; space systems; etc. Indeed, it seems there is almost no

end to the use of the word “system” in today’s society.

CO-DESIGNING SOLUTIONS – “Co-design” refers to a participatory

approach to designing solutions, in which community members are treated

as equal collaborators in the design process. Co-design is also a well-

established approach to creative practice, particularly within the public

sector.

Example:

Hosting public events

Conducting feedback surveys

Collaborating on open-source tools

Posting things on Google Docs to solicit comments

Hosting design workshops

Gathering experts to comment

User testing

MONITOR, REFLECT AND ADAPT – monitoring the entire system by

viewing multiple inputs being processed or transformed to produce outputs

while continuously gathering feedback on each part in system thinking.

Reflective thinking means taking the bigger picture and understanding all of

its consequences. It doesn’t mean that you’re just going to simply write

down your future plans or what you’ve done in the past. Moreover, because

complex adaptive systems are continually evolving, systems thinking is

oriented towards organizational and social learning – and adaptive

management.

Example: examples include ecosystems, cars and human bodies as well as

organizations

DIALOGUE AND COLLABORATION – The practice of collaborative

learning moves relationships beyond the mere exchange of information that

characterizes most project teams or corporate partnerships. Dialogue,

however, is a discipline of collective learning and inquiry. It can serve as a

cornerstone for organizational learning by providing an environment in

which people can reflect together and transform the ground out of which

their thinking and acting emerges. Dialogue is not merely a strategy for

helping people talk together. In fact, dialogue often leads to new levels of

coordinated action without the artificial, often tedious process of creating

action plans and using consensus-based decision-making. Dialogue does not

require agreement; instead it encourages people to participate in a pool of

shared meaning, which leads to aligned action.

Example: For example, labor and management representatives from a steel

mill have discovered dramatic shifts in their ways of thinking and talking

together. In a recent presentation by this dialogue group, one union

participant said, “We have learned to question fundamental categories and

labels that we have applied to each other.”

“Can you give us an example?” one manager asked.

“Yes,” he responded, “labels like management and union.”

This particular group has transformed a 50-year-old adversarial

relationship into one where there is genuine and serious inquiry into “taken-

for-granted” ways of thinking. The steelworkers, for example, recognized

that they had far more in common with management than they had

previously realized or expected. “We quit talking about the past,” said the

Union President.“ We didn’t bring any of that up, all the hurt and mistrust

that we’ve had over the last twenty years.” Another steelworker noticed that

the category “union” limited him as much as it protected him.“ It’s

important to suspend the word ‘union,’” he said.

You might also like

- Dynamic DialogueDocument2 pagesDynamic DialogueWangshosan100% (1)

- MS 10Document7 pagesMS 10Rajni KumariNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 - Entrepreneurship - Management - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inDocument41 pagesUnit 2 - Entrepreneurship - Management - WWW - Rgpvnotes.inRhode MarshallNo ratings yet

- CDE Model: Description of CDDocument5 pagesCDE Model: Description of CDcao.heng.caoNo ratings yet

- Learning OrganizationDocument15 pagesLearning Organizationliveeducation100% (7)

- Systems Thinking Course at Schumacher CollegeDocument3 pagesSystems Thinking Course at Schumacher Collegekasiv_8No ratings yet

- Organizational Processes through Communication LensDocument19 pagesOrganizational Processes through Communication LensAnendya ChakmaNo ratings yet

- Tsoukas and Chia (2002) On Change'.fullDocument16 pagesTsoukas and Chia (2002) On Change'.fullSaurav Gupta100% (1)

- On Organisational Becoming - Tsoukas ChiaDocument17 pagesOn Organisational Becoming - Tsoukas Chialle_91No ratings yet

- Action Reserach Change Capacity EGOS1Document25 pagesAction Reserach Change Capacity EGOS1Ghina RahmaniNo ratings yet

- Generative Design: A Paradigm For Design ResearchDocument8 pagesGenerative Design: A Paradigm For Design ResearchM. Y. HassanNo ratings yet

- Brief Introduction To Soft Systems Thinking and Adaptive Systems - ST4S39Document4 pagesBrief Introduction To Soft Systems Thinking and Adaptive Systems - ST4S39Abel Jnr Ofoe-OsabuteyNo ratings yet

- What Might Systemic Innovation Be?Document43 pagesWhat Might Systemic Innovation Be?danielm_nlNo ratings yet

- Academy of Management Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Academy of Management JournalDocument39 pagesAcademy of Management Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Academy of Management Journalsongül ÇALIŞKANNo ratings yet

- Peter Senge and The Learning OrganizationDocument15 pagesPeter Senge and The Learning OrganizationMarc RomeroNo ratings yet

- Jones Design Principles For Social Systems Preprint-with-cover-page-V2Document32 pagesJones Design Principles For Social Systems Preprint-with-cover-page-V2Muhammad Arif DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Tlale-Romm2018 Article SystemicThinkingAndPracticeTowDocument16 pagesTlale-Romm2018 Article SystemicThinkingAndPracticeTowlizamarai454No ratings yet

- Projects As DifferenceDocument6 pagesProjects As DifferenceMarkusKoernerNo ratings yet

- Appreciative Inquiry Approach to Community ChangeDocument19 pagesAppreciative Inquiry Approach to Community ChangeGopal GhimireNo ratings yet

- Creativity LitreviewDocument17 pagesCreativity LitreviewAbreham AwokeNo ratings yet

- Designing For Social JusticeDocument60 pagesDesigning For Social JusticePablo Abril Contreras100% (1)

- Managing Future OrganizationDocument6 pagesManaging Future OrganizationsamayiqueNo ratings yet

- Keeping An Eye On The Mirror: Image and Identity in Organizational AdaptationDocument39 pagesKeeping An Eye On The Mirror: Image and Identity in Organizational AdaptationgiselesclNo ratings yet

- Historical Theories of ManagementDocument3 pagesHistorical Theories of ManagementokwesiliezeNo ratings yet

- Dti Executive Summary Website VersionDocument21 pagesDti Executive Summary Website VersionFranco PisanoNo ratings yet

- Congruence Model PDFDocument16 pagesCongruence Model PDFAndré Amaro100% (2)

- Structured Methods in Product DevelopmentDocument10 pagesStructured Methods in Product DevelopmentRenz PamintuanNo ratings yet

- BUAD 801 TipsDocument53 pagesBUAD 801 TipsZainab IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Grounded Theory Research MethodsDocument13 pagesGrounded Theory Research MethodsArturo CostaNo ratings yet

- Modelo de CambioDocument14 pagesModelo de CambioCynthia MuñozNo ratings yet

- Pre Print Adam Ledunois Damart GDN Handbook2019Document13 pagesPre Print Adam Ledunois Damart GDN Handbook2019irdhina.harithNo ratings yet

- Scriptapedia: A Digital Commons For Documenting and Sharing Group Model Building ScriptsDocument16 pagesScriptapedia: A Digital Commons For Documenting and Sharing Group Model Building Scriptsjueguito lolNo ratings yet

- Jones2017 The Systemic TurnDocument7 pagesJones2017 The Systemic Turnjuan acuñaNo ratings yet

- Garbage Can ModelDocument26 pagesGarbage Can ModelDominique NunesNo ratings yet

- Jones - 2014 - Systemic Design Principles For Complex Social Systems. in Social Systems and Design (Pp. 91-128)Document38 pagesJones - 2014 - Systemic Design Principles For Complex Social Systems. in Social Systems and Design (Pp. 91-128)Mario AngaritaNo ratings yet

- 03 - Models of CreativityDocument5 pages03 - Models of CreativityLaura Sofia Avila CardozoNo ratings yet

- Overlapping Talk and The Organization of Turn-Taking For ConversationDocument64 pagesOverlapping Talk and The Organization of Turn-Taking For ConversationPriha LechsaNo ratings yet

- Zavala - 2008 - Organizational - Analysis - of - Software - Organizations - Oktabaorganization Analysisexc PDFDocument41 pagesZavala - 2008 - Organizational - Analysis - of - Software - Organizations - Oktabaorganization Analysisexc PDFAshok Chowdary GNo ratings yet

- A Multi-Systems Theory of Organizational CommunicationDocument40 pagesA Multi-Systems Theory of Organizational CommunicationREFILWENo ratings yet

- 06 Perrow-1967Document16 pages06 Perrow-1967sagitario2009No ratings yet

- The Architecture of Complexity: Culture and Organization July 2003Document18 pagesThe Architecture of Complexity: Culture and Organization July 2003Madiha NasirNo ratings yet

- 3370 ArticleText 16947 5 10 20201211Document47 pages3370 ArticleText 16947 5 10 20201211vincentNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Complex Learning EnvironmentsDocument24 pagesThe Analysis of Complex Learning Environmentspablor127100% (1)

- Vinod - OD - Notes PDFDocument16 pagesVinod - OD - Notes PDFnannawarevinod1No ratings yet

- System ThinkingDocument18 pagesSystem Thinkingpptam50% (2)

- Lozano 2012Document21 pagesLozano 2012Grecia V. MuñozNo ratings yet

- Stupidity Accepted FinalDocument62 pagesStupidity Accepted Finalsergio montañoNo ratings yet

- Salet, Faludi: Strategy of Direct Reciprocity As Solution: Applications in Practice: ObjectionsDocument16 pagesSalet, Faludi: Strategy of Direct Reciprocity As Solution: Applications in Practice: Objectionsmeri22No ratings yet

- Group and Team Processes in OrganisationsDocument29 pagesGroup and Team Processes in OrganisationsSamrah QamarNo ratings yet

- Lomi HarrisonDocument16 pagesLomi HarrisonClaude Caliao EliseoNo ratings yet

- Evolution of O.D.Document68 pagesEvolution of O.D.Salim KhojaNo ratings yet

- Application of Case Studies to Engineering Management and Systems Engineering EducationDocument18 pagesApplication of Case Studies to Engineering Management and Systems Engineering EducationNeoly Fee CuberoNo ratings yet

- Chidambaran 2005Document21 pagesChidambaran 2005rizki prahmanaNo ratings yet

- How Knowledge Transfer Impacts Performance: A Multilevel Model of Benefits and LiabilitiesDocument19 pagesHow Knowledge Transfer Impacts Performance: A Multilevel Model of Benefits and LiabilitiesRanion EuNo ratings yet

- Bedwell Et Al, 2012 PDFDocument18 pagesBedwell Et Al, 2012 PDFMarietou SidibeNo ratings yet

- Creative Design Situations: Artificial Creativity in Communities of Design AgentsDocument9 pagesCreative Design Situations: Artificial Creativity in Communities of Design AgentsDanteANo ratings yet

- Critique Paper Dev CommDocument17 pagesCritique Paper Dev CommRacheljygNo ratings yet

- Performance Task#6 - Russell Glenn S. Comia - BS INFO - 3SMP1Document11 pagesPerformance Task#6 - Russell Glenn S. Comia - BS INFO - 3SMP1Rochelle Marie RegenciaNo ratings yet

- Capstone Project Title:: A Water Billing Sytem With Due Date Sms Notification in Dolores, QuezonDocument2 pagesCapstone Project Title:: A Water Billing Sytem With Due Date Sms Notification in Dolores, QuezonRochelle Marie Regencia100% (1)

- Project vs Program Management RolesDocument5 pagesProject vs Program Management RolesRochelle Marie RegenciaNo ratings yet

- Script in Interview MAM EspiDocument2 pagesScript in Interview MAM EspiRochelle Marie RegenciaNo ratings yet

- Team UnityDocument4 pagesTeam UnityRochelle Marie RegenciaNo ratings yet

- Shredded Paper Pots HannaDocument5 pagesShredded Paper Pots HannaRochelle Marie RegenciaNo ratings yet

- Financial ManagementDocument18 pagesFinancial ManagementRochelle Marie RegenciaNo ratings yet

- Business Plan Sky's Tuna Veggie BallsDocument1 pageBusiness Plan Sky's Tuna Veggie BallsRochelle Marie RegenciaNo ratings yet

- Trace Log 20131229152625Document3 pagesTrace Log 20131229152625Razvan PaleaNo ratings yet

- Building C# Applications: Unit - 2Document25 pagesBuilding C# Applications: Unit - 2mgsumaNo ratings yet

- GPU, A Gnutella Processing UnitDocument27 pagesGPU, A Gnutella Processing UnitMengotti Tiziano FlavioNo ratings yet

- S Sss 001Document4 pagesS Sss 001andy175No ratings yet

- George Washington's Presidency NotesDocument5 pagesGeorge Washington's Presidency Notesf kNo ratings yet

- Installation Instruction: Q/fit Piping On Base MachineDocument11 pagesInstallation Instruction: Q/fit Piping On Base MachineJULY VIVIANA HUESO VEGANo ratings yet

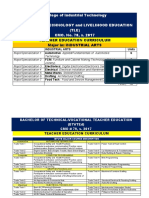

- College of Industrial Technology Bachelor of Technology and Livelihood Education (TLE) CMO. No. 78, S. 2017Document5 pagesCollege of Industrial Technology Bachelor of Technology and Livelihood Education (TLE) CMO. No. 78, S. 2017Industrial TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Water Supply NED ArticleDocument22 pagesWater Supply NED Articlejulie1805No ratings yet

- Lesson2.1-Chapter 8-Fundamentals of Capital BudgetingDocument6 pagesLesson2.1-Chapter 8-Fundamentals of Capital BudgetingMeriam HaouesNo ratings yet

- 03board of Directors Resolution For AGRONetBIZ ENGLISHDocument1 page03board of Directors Resolution For AGRONetBIZ ENGLISHyuswirdaNo ratings yet

- Geology and age of the Parguaza rapakivi granite, VenezuelaDocument6 pagesGeology and age of the Parguaza rapakivi granite, VenezuelaCoordinador de GeoquímicaNo ratings yet

- PTL Ls Programme HandbookDocument34 pagesPTL Ls Programme Handbooksalak946290No ratings yet

- KEDIT User's GuideDocument294 pagesKEDIT User's GuidezamNo ratings yet

- Market Segmentation Targeting Strategy and Positioning Strategy Performance Effects To The Tourists Satisfaction Research in Pangandaran Beach Pangandaran DistrictDocument10 pagesMarket Segmentation Targeting Strategy and Positioning Strategy Performance Effects To The Tourists Satisfaction Research in Pangandaran Beach Pangandaran DistrictRizki Kurnia husainNo ratings yet

- FLIX Booking 1068813091Document2 pagesFLIX Booking 1068813091Pavan SadaraNo ratings yet

- Nimt Institute of Method & Law, Greater Noida: "Legal Bases and Issues in Scrapping Article 370"Document12 pagesNimt Institute of Method & Law, Greater Noida: "Legal Bases and Issues in Scrapping Article 370"Preetish Sahu100% (1)

- Hospital Management System Synopsis and Project ReportDocument152 pagesHospital Management System Synopsis and Project ReportKapil Vermani100% (1)

- 1.3 Swot and PDP AnalysisDocument4 pages1.3 Swot and PDP AnalysismiroyNo ratings yet

- Global CityDocument3 pagesGlobal Citycr lamigoNo ratings yet

- 229 PGTRB Commerce Study Material Unit 15 and 16Document16 pages229 PGTRB Commerce Study Material Unit 15 and 16shareena ppNo ratings yet

- 001-Numerical Solution of Non Linear EquationsDocument16 pages001-Numerical Solution of Non Linear EquationsAyman ElshahatNo ratings yet

- Etextbook 978 0078025884 Accounting Information Systems 4th EditionDocument61 pagesEtextbook 978 0078025884 Accounting Information Systems 4th Editionmark.dame383100% (49)

- CPQMDocument2 pagesCPQMOlayinkaAweNo ratings yet

- PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT Model Questions - ADocument4 pagesPRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT Model Questions - ALionel MintsaNo ratings yet

- Wedding Planning GuideDocument159 pagesWedding Planning GuideRituparna Majumder0% (1)

- Introduction To Major Crop FieldsDocument32 pagesIntroduction To Major Crop FieldsCHANDANINo ratings yet

- Acute AppendicitisDocument51 pagesAcute AppendicitisPauloCostaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Arsenio C. Villalon, Jr. For Petitioner. Labaguis, Loyola, Angara & Associates For Private RespondentDocument43 pagesSupreme Court: Arsenio C. Villalon, Jr. For Petitioner. Labaguis, Loyola, Angara & Associates For Private RespondentpiaNo ratings yet

- Agreement: /ECE/324/Rev.2/Add.127 /ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.2/Add.127Document29 pagesAgreement: /ECE/324/Rev.2/Add.127 /ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.2/Add.127Mina RemonNo ratings yet

- EY - NASSCOM - M&A Trends and Outlook - Technology Services VF - 0Document35 pagesEY - NASSCOM - M&A Trends and Outlook - Technology Services VF - 0Tejas JosephNo ratings yet