Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jordana Blejmar Sobre Not One Less

Uploaded by

maria pia lopezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jordana Blejmar Sobre Not One Less

Uploaded by

maria pia lopezCopyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.

pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

Roundtable on María Pia López’s Not One Less:

Mourning, Disobedience, and Desire

SPECIAL SECTION

Introduction

Latin American Feminisms, a Land

of Political Experimentation

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

JORDANA BLEJMAR

abstract On June 3, 2015, thousands of people in Argentina gathered in the streets to protest the mur

der of fourteen-year-old Chiara Paez at the hands of her boyfriend. Following her brutal death, a wave

of indignation spread on social media with the viral hashtags #NiUnaMenos and #VivasNosQueremos.

What started as an act of public grief and defiance against patriarchy rapidly found an angry but also

unexpectedly upbeat tone, a combination of collective fury and exhaustion expressed in highly theatri

cal and political performances of affection and resistance. “We are moved by desire” became one of the

movement’s taglines. María Pia López’s Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and Desire (2021), among the

first English accounts from inside the movement, reflects on this phenomen on and serves as a practical

tool in current feminist struggles, feeding the very same transnational, intersectional, transformative

movement in which the author has participated as protagonist, connoisseur, and chronicler. López is one

of the leading voices of the fourth wave of Latin American feminisms. This collection of commentar

ies is animated by the dialogical spirit of her book, addressing issues ranging from the transnational

identity of feminist political activism; the connection between gender equality and class struggle; the

movement’s combination of mourning, ecstasy, and desire; and—arguably one of the most important

achievements of NUM—feminism’s ability to alter the political imagination and common sense.

keywords María Pia López, Not One Less, feminism, Latin America, desire

In 1997 María Pia López published Mutantes: Trazos sobre los cuerpos (Mutants: Strokes

on Bodies), a brief but striking essay on the politics and poetics of the body in Latin

America during the twentieth century. López examined multiple attempts to disci

pline, restrain, and punish vulnerable bodies in the region and, in turn, the strate

gies used by those bodies to gather in public and contest diverse abuses of power.

Focusing on Argentina, she proposed a genealogy of corporeal political experi

ences, which included the sacrificial idea of poner el cuerpo (to put the body at risk)

that animated the armed struggles of the 1970s, the absent and spectral bodies

CRITICAL TIMES | 5:1 | APRIL 2022

DOI 10 . 1215/26410478-9536567 | © 2022 Jordana Blejmar

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). 218

disappeared during the 1976–83 dictatorship, and the secluded bodies of the neo

SPECIAL SECTION | Roundtable on María Pia López’s Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and Desire

liberal 1990s—the time when she was writing the book—when politics was con

ceived as a spectacle that se mira y no se toca: seen, usually on TV, but not touched.

State terror and fear, López argued, created inactive political subjects, with

drawn from political struggles and immersed in what she called the “tactics of the

ostrich,” bodies imprisoned in their homes, connected to the public only through

the reception of power. These bodies produced “una forma hasta ahora exitosa de

hacer política. . . . Pero por supuesto tampoco esto es irreversible: el presente aún

puede ser materia de la acción” (a means of enacting politics that has—to date—

been successful. . . . But which is also not irreversible: the present can still be a

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

site for action).1

Fast-forward to the publication of Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and

Desire and we confront a very different reality. The global COVID-19 pandemic has

forced us allto stay indoors. But unlike during the 1990s in Argentina, this new

form of bodily confinement has neither produced inactive political subjects nor

stopped the powerful green tide led by thousands of Latin American women since

the emergence of the Not One Less movement in 2015. In March of that year a

group of feminist activists and writers (including López, at the time the director

of the National Library’s Museo del Libro y de la Lengua in Buenos Aires) orga

nized a reading marathon with the slogan “Not One Less,” a verse used by Mexican

poet and activist Susana Chávez Castillo in 1995 to protest the femicides of Ciudad

Juárez. “Ni una menos, ni una muerta más” (“not one less, not one dead more”) was

the original phrase used by Chávez Castillo, murdered in 2011 for denouncing the

murders of women in Mexico. On May 10, 2015, the tweet “#NotOneLess. We Want

to be Alive.” went viral. Five years later, the movement achieved one of its most sig

nificant victories, the legalization of abortion in Argentina, by far the largest of the

handful of countries in the region to guarantee this right to women.

The pandemic and this new wave of feminism are not unrelated. As UN Women

recently declared, femicides are the “other” pandemic, more dangerous now than

ever before as many vulnerable women and dissident genders have been forced to

spend more time indoors with their aggressors.2 The pandemic has even been used

perversely by some governments to regain control of the streets. Nelly Richard, one

of the most renowned cultural critics in Latin America, has suggested, for example,

that for Chilean president Sebastián Piñera, lockdown has been an opportunity to

“disinfect” (higienizar) the capital city of social revolts and the echoes of the rebel

lions against the government that took place in early 2020 and were led by young

Chilean women and students.3 At the same time, the pandemic has highlighted the

strength of some of the legacies of feminist movements around the globe, not least

because, if vulnerable women can now rely on each other, that is partly thanks to

BLEJMAR | INTRODUCTION | 219

previously established, and viral, networks of affective care (políticas del cuidado)

and solidarity.4

López’s book was written in dialogue with the voices and experiences of many

other women and compañerxs who have participated in and written about contem

porary Latin American feminist movements. The book is also entwined with the

memories and words of women who led previous struggles that laid the founda

tions for today’s battles. “Disobedience has a history,” write Natalia Brizuela and

Leticia Sabsay in their introduction to the book, “in fact many histories.”5 López

chronicles those intersectional and transnational trajectories, from popular move

ments such as that of the suffragists and the piqueteras to LGBTQI acts of disobedi

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

ence and the weekly rounds of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo. If feminists have often

been compared to mythical figures with negative connotations such as witches or

Medea (the mother who killed her children), Latin American women’s movements

have been equally inspired by fictional and mythical characters of transgression

such as La Malinche, the native polyglot woman given as a trophy of conquest to

Hernan Cortés, and Antigone, a “feminine figure who defies the state through a

powerful set of physical and linguistic acts.”6

In this history of Latin American feminisms, there are victims—the captive

women of the nineteenth century, the kidnapped women of the Zwi Migdal ring,

the desaparecidas, the victims of femicides—but there is not victimization. There

are “killjoys” but not amargadas (bitter women), as feminists have often been

labeled by anti-rights activists.7 There is (public) mourning, and if any semblance

of melancholia is present it is only in the sense set out by Butler and Christian Gun

dermann when analyzing the myth of Antigone, that is, not as a paralyzing effect

of trauma but as an act of political resistance in the face of neoliberal demands

for oblivion.8 “The tone is festive,” says López, because Not One Less operates, in

Gago’s words (cited by Brizuela and Sabsay), on the basis of “preserving vitalism”

and “to safeguard the expansions of liberties, joy, pleasure and affects.”9 The vital

ist nature of the movement opposes itself to the conception of the female body as

ungrievable or as rubbish, symbolized by the bodies used and disposed of in black

plastic bags by the perpetrators of femicides.

As a leading scholar in contemporary Latin America, López writes as a sociolo

gist. But she also writes from what she calls a “sensory experience,” the experience

of being a woman in Argentina, the experience of humiliation and shame, but also

of joy, euphoria, and desire (“We are moved by desire” is one of the movement’s

slogans). The book thus has a clear political objective. It aims to impede the move

ment’s “conservative appropriation and stop the work being done from devolving

into something purely ornamental.” Because in the battle against patriarchy the

performance of words matters in equal measure to that of bodies.

CRITICAL TIMES 5:1 | APRIL 2022 | 220

“Ahora devuélvanos la palabra ‘vida’” (Now give us back the word “life”),

SPECIAL SECTION | Roundtable on María Pia López’s Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and Desire

demanded a tweet by a feminist in Argentina hours after the vote in the Senate

to legalize abortion on December 30, 2020. The tweet referred to the slogan “Let’s

protect both lives” used by antirights activists, a slogan that appropriates a word,

vida, that belongs to everyone. In her book, López examines the inverse operation,

that is, how certain words—notably “revolution” and “strike”—were taken up by

the current feminist movement to acknowledge a lineage of disobedience and

resistance. Crucially, though, this legacy is not received passively by contemporary

feminists but rather transformed in the very act of transmission. As Egyptian psy

choanalyst Jacques Hassoun argued, successful transmission offers to the heir the

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

freedom to betray heritage so as to better find it.10

Thus, if the current feminist movement is a “revolution,” it is a specific type

of revolution: it has no boss, no leader, no owner, and not just one spokeswoman.

This revolution is also nonsacrificial. In fact, says López, the feminist movement is

the opposite of a sacrifice. Moreover, if the revolution sought by the armed groups

of the 1960s and 1970s believed that violence and la guerra revolucionaria (the rev

olutionary war) was necessary to respond to and ultimately counteract a violence

already installed in society,11 the feminist revolution is nonviolent. As Judith Butler

explains,

Nonviolence is often misunderstood as a passive practice that emanates from a calm

region of the soul, or as an individualist ethical relation to existing forms of power.

But, in fact, nonviolence is an ethical position found in the midst of the political field.

An aggressive form of nonviolence accepts that hostility is part of our psychic consti

tution, but values ambivalence as a way of checking the conversion of aggression into

violence.12

Butler further claims that “nonviolence is less a failure of action than a physical

assertion of the claims of life, a living assertion, a claim that is made by speech,

gesture and action, through networks, encampments, and assemblies; allof these

seek to recast the living as worthy of value, as potentially grievable, precisely under

conditions in which they are either erased from view or cast into irreversible forms

of precarity.”13 She specifically mentions Latin American femicidios (caused by the

failure of institutions including the police and the legal system, coupled with cul

tures of terror inherited from periods of state authoritarianism) and the practices

of Ni una menos to illustrate the strength of nonviolent movements built around

alliances of solidarity and resistance.

The International Women’s Strike that takes place every March 8 allover the

world is also inspired by many other strikes in the history of popular movements.

BLEJMAR | INTRODUCTION | 221

Yet, just like the feminist revolution, the feminist strike has its own characteristics:

it is “immeasurable because the notion of work that it acknowledges and aims to

interrupt is not unidimensional,” says López. “It does not accept the reduction of

work to its paid incarnation but encompasses allproductive labor, creative force,

moulding of material, weaving of community ties.”14

Far from being a distant chronicle of the events, Not One Less is not only the

book of an activist but also a book that is itself activism and a reminder of the per

formative power of both words and emotions. The editors’ decision to commission

a translator (Frances Riddle) and publish it in English in the prestigious Critical

Theory series of Polity Press is, in turn, another political act. It aims to continue

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

the open conversation started by López and open it up to other geopolitical and

affective horizons.

It is with that expansive and inclusive spirit that this dossier includes com

mentaries from six highly respected feminist activists and scholars from different

parts of the world: Sarah Banet-Weiser (United States), Karen Benezra (United

States), Alejandra Castillo (Chile), Claudia Salazar Jiménez (Peru), Lidia Salvatori

(Italy), and Cecilia Sosa (Argentina). We were keen to include scholars working on

the intersections between feminist struggles and race struggles because, as López

says, “the emancipation of women cannot be limited to the few, to the white, or the

rich.”15 Yet this dossier is not fully representative of the plurality of voices that con

stitute Latin American women’s movements. Nonetheless, it remains another rhi

zomatic intervention in the intersectional, interracial, interclass, and international

exchanges and conversations that circulate in and through diverse feminisms.

In her contribution, Karen Benezra attempts to decipher the theoretical frame

work and political stakes of López’s essay. She is particularly interested in López’s

explicit or implicit dialogues with Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Jacques Lacan and

how the personal and collective experiences of being a woman reveal ontological

rather than merely anthropological or biological questions. Benezra not only reads

López in the practice of the discurrir libre but also suggests that López’s book goes

beyond that tradition of the Latin American essay by playing a performative func

tion. She points out how “the book’s apparent systematicity is not merely an aes

thetic choice” but sustains “a theoretical question that has yet to be determined

politically.” Proposing a comparison with Verónica Gago’s Feminist International: How

to Change Everything (2020), Benezra draws out López’s caution around the move

ment’s ability to articulate liberal claims on gender equality with class struggle.

López’s unusual combination of theory and activism, says Cecilia Sosa, creates

an “affective genre” that fits the central role that “desire” and other emotions have

in the Not One Less movement, where mourning is paired with a kind of “ecstasy”

that we often see in marches and demonstrations, which are both protests and

CRITICAL TIMES 5:1 | APRIL 2022 | 222

celebrations of sisterhood and togetherness. This festive spirit, Sosa argues, distin

SPECIAL SECTION | Roundtable on María Pia López’s Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and Desire

guishes NUM both from their more “austere” counterpart movements in the North

as well as previous generations of women in the region, notably the Mothers of

Plaza de Mayo in Argentina. For Sosa, the encounter between the Mothers’ white

scarves and the green scarves first used by young activists in the campaigns for

legal abortion in Argentina can be read as the passage from a form of activism

based on blood ties and firsthand victims to one comprising “anonymous activists

with no further credentials, willing to join an impure activist lineage, which shall

remain open to allsorts of assortments, combinations, and libidinous mixtures.” In

her reading of López’s book, Sosa also highlights one of the risks of contemporary

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

femin ism, namely that it can become a capitalist maneuver to keep us allon the so-

called progressive side. The Not One Less movement has so far escaped the danger

of capitalist appropriation, Sosa argues, by hosting instead a deep transformation

of interaction, sensibility, and sexuality.

Echoing the transnational nature of the movement and the feminist practice of

thinking together that animates López’s book, Lidia Salvatori, who shares with López

a place of enunciation that entwines feminist activism, autoethnography, and criti

cal discourse, connects the Latin American expression “Ni una Menos” to its Italian

counterpart, Non Una Di Meno, launched publicly in November 2016 when thou

sands of Italian women protested in the street, enraged by the femicide of Sara di

Pietrantionio, killed and set on fire by her partner. Salvatori suggests that “the call

of Not One Less has contributed to the formation of a transnational identity and

conceptualization rather than a transnational organizational structure”: a distinc

tion that points both to what the movement has already achieved with its “spon

taneous contamination” of practices and slogans, facilitated by new technologies

and a globalized horizon, and to what the movement might aspire to become truly

international. One might also argue that the absence of a transnational organiza

tional structure is in fact what gives the Not One Less movement its diverse nature,

the possibility of adapting itself to local realities and circumstances without losing

sight of the common goals in both national or regional contexts. Either way, Sal

vatori argues, the recognition of a transnational and intercontinental sisterhood

is crucial to resisting xenophobic and neoconservative forces that, particularly in

Europe and in the United States under the Trump administration, have become

expressions of the antirights movement.

Both Claudia Salazar Jiménez and Sarah Banet-Weiser stress in their interven

tions the need to tie the contemporary feminist movements in Latin America to

issues of race and colonialism. Peruvian feminist scholar Salazar Jiménez writes

that, compared to Argentina, Peru is often seen as “the caboose of the feminist

movement: one of the last to recognize sexual and reproductive rights.” While that

BLEJMAR | INTRODUCTION | 223

is true, Salazar Jiménez draws out the contributions made by Peruvian thinkers

to the collective efforts of women in the region, notably those set out by French-

Peruvian author Flora Tristán, who “helped López to point out the double neglect

to which the female proletariat has been subjected, both by Marxism (which only

speaks of the male one) and by feminism (which overlooked the working class).”

The colonial and racist aspects of historical oppression against women and dissi

dent genders—including forced sterilizations of Andean women during Fujimori’s

regime—are also inscribed in the chants of both the women who proudly recog

nize themselves as the “granddaughters of the witches you weren’t able to burn”

and also the antirights male protesters who claim proudly that they are “the sons

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

of the inquisitors.”

US-based scholar Sarah Banet-Weiser celebrates the emergence of the Not

One Less popular movement and distinguishes it from two other forms of the

popular/populist in the North. On the one hand she puts NUM into dialogue with

the predominantly white men who stormed the US Capitol in Washington, DC,

on January 6, 2021. She sets the intertwined discourses of white supremacy and

machismo in contrast to “the kind of collective subject, which links vulnerability

resistance and agency across difference.” She also makes a distinction between

Latin American popular feminism—a collective and common struggle—and the

“highly visible and mediated neoliberal femin ism that has gained dominance in

the Anglo-American world in recent years,” a melancholic phenomenon of white

mainstream feminism focused on individual grievances and the impossibility of

moving past the self. Both the populist white nationalist storming of the US Capi

tol and Anglo-American popular feminisms base the figure of the victim around a

claim of a “neoliberal ground of individualism that is designed to render those who

are marginalized or engaged in collective struggles invisible.” By contrast, the NUM

movement is inclusive, intersectional, international, and interracial, and instead of

looking melancholically and nostalgically to the past, it fights for collective futures.

Finally, Chilean scholar and feminist activist Alejandra Castillo also highlights

femin ism’s capacity to alter the common sense of politics and to expand the politi

cal imagin ation. She discusses the force of images in López’s book, especially those

of the mythical figures of Antigone and Demeter, the mother in search of her kid

napped daughter, figures that were paradoxically invented by men trying to imag

ine the body and the experiences of women in mourning. Castillo argues that it is

now time to build our own repertoire of inspiring female models. Both Antigone

and Demeter are commendable women, but they fight, and mourn, alone. The Not

One Less movement offers an alternative narrative, where mourning becomes a

collective and public experience, the foundation for a new poiesis.

All the commentaries included here highlight a key aspect of López’s book: that,

as the author herself puts it, “feminism is a land of great political experimentation,”

CRITICAL TIMES 5:1 | APRIL 2022 | 224

and that the alliances and complicities between struggles against different types of

SPECIAL SECTION | Roundtable on María Pia López’s Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and Desire

sexual, racial, class, and neoliberal oppression prove that feminism is not just una

cosa de mujeres but, in Verónica Gago’s words, the desire “to change everything.”16

Such changes should also take place within academia, especially Anglo-Saxon

academia, with its logics of exclusion and rigid registers of writing. Lidia Salva

tori claims that López’s book “is an act of recognition of the collective dimension

of knowledge production in contrast with the tendency to measure and reward

individual achievements, typical of neoliberal academia.” Similarly, Karen Bene

zra stresses that López’s text “refuses to offer itself as an object of university

discourse—not through an appeal to feminine desire but rather through an unre

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

mitting political realism.” Cecilia Sosa recalls meeting López as a sociology student

at the University of Buenos Aires, that “massive, free and public university, where

‘public’ stands at the antipodes of the British elitist standards.” Finally, Claudia

Salazar Jiménez also commends López’s unique style of writing, which invites us

to imagine alternative readers for our work. In sharp contrast to the “ideal” reader

of academic writing, which she imagines as an “anonymous male, who stands as a

wall to which one speaks but who maintains a silent distance,” this dossier demon

strates that another type of interlocutor is still possible.

JORDANA BLEJMAR is senior lecturer in visual media and cultural studies at the

University of Liverpool. Originally a literature graduate from the University of Buenos

Aires, she received her doctorate from the University of Cambridge. She is the author of

Playful Memories: The Autofictional Turn in Post-dictatorship Argentina (2016) and the coed

itor of three books on art and politics in Latin America. She has curated art and photo

graphic exhibitions in Buenos Aires, Liverpool, and Paris. She is a member of the editorial

board of the Bulletin of Hispanic Studies and the PI of the AHRC-funded project Cold War

Toys: Material Cultures of Childhood in Argentina (2022–24).

Notes

1. López, Mutantes, 79; my emphasis.

2. UN Women, “Urgent Action.”

3. Richard, “Imaginaries of Revolt.”

4. Gago and Cavallero, “Deuda.”

5. Brizuela and Sabsay, foreword, x.

6. Butler, Antigone’s Claim, 2.

7. Ahmed, Living.

8. Gundermann, Actos melancólicos, 47.

9. Brizuela and Sabsay, foreword, xv.

10. Hassoun, Les contrebandiers.

11. Calveiro, Política y/o violencia.

12. Butler, Force of Nonviolence, 5.

13. Butler, Force of Nonviolence, 19.

BLEJMAR | INTRODUCTION | 225

14. López, Not One Less, 49.

15. López, Not One Less, 3.

16. Gago, Feminist International.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.

Butler, Judith. Antigone’s Claim: Kinship between Life and Death. New York: Columbia University

Press, 2000.

Butler, Judith. The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethical Political Bind. London: Verso Books, 2020.

Brizuela, Natalia, and Leticia Sabsay. Foreword to Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and

Desire, by María Pia López, translated by Frances Riddle, vi–xvi. London: Polity, 2020.

Calveiro, Pilar. Política y/o violencia: Una aproximación a la guerrilla de los años 70. Buenos Aires:

Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article-pdf/5/1/218/1589307/218blejmar.pdf by guest on 14 June 2022

Norma, 2005.

Gago, Verónica. Feminist International: How to Change Everything. London: Verso, 2020.

Gago, Verónica, and Luci Cavallero. “Deuda, vivienda y trabajo: Una agenda feminista para la

pospandemia.” Revista Anfibia, September 4, 2020. https://revistaanfibia.com/ensayo/deuda

-vivienda-trabajo-una-agenda-feminista-la-pospandemia/.

Gundermann, Christian. Actos meláncólicos: Formas de resistencia en la postdictadura argentina.

Rosario, Argentina: Beatriz Viterbo Editora, 2007.

Hassoun, Jacques. Les contrebandiers de la mémoire. Paris: Eres, 2011.

López, María Pia. Mutantes: Trazos sobre los cuerpos. Buenos Aires: Colihue, 1997.

López, María Pia. Not One Less: Mourning, Disobedience, and Desire. Translated by Frances Riddle.

London: Polity, 2020.

Richard, Nelly. “Imaginaries of Revolt, Archive of Life, and Experience Reshaped from the Pan

demic.” Online seminar, Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid, September, 21, 2020.

UN Women. “Urgent Action Needed to End Pandemic of Femicide and Violence against Women,

Says UN Expert.” UN Women, November 20, 2020. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news

/stories/2020/11/statement-dubravka-simonovic-special-rapporteur-on-violence-against

-women.

CRITICAL TIMES 5:1 | APRIL 2022 | 226

You might also like

- Genocide in the Neighborhood: State Violence, Popular Justice, and the ‘Escrache’From EverandGenocide in the Neighborhood: State Violence, Popular Justice, and the ‘Escrache’No ratings yet

- Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the AmericasFrom EverandBeyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the AmericasRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- From #BlackLivesMatter to Black LiberationFrom EverandFrom #BlackLivesMatter to Black LiberationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (23)

- Surviving State Terror: Women’s Testimonies of Repression and Resistance in ArgentinaFrom EverandSurviving State Terror: Women’s Testimonies of Repression and Resistance in ArgentinaNo ratings yet

- Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded CountryFrom EverandGrieving: Dispatches from a Wounded CountryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights MovementFrom EverandFeminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights MovementNo ratings yet

- Speaking Truths: Young Adults, Identity, and Spoken Word ActivismFrom EverandSpeaking Truths: Young Adults, Identity, and Spoken Word ActivismNo ratings yet

- Radical Women in Latin America: Left and RightFrom EverandRadical Women in Latin America: Left and RightRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Living the Revolution: Italian Women's Resistance and Radicalism in New York City, 1880-1945From EverandLiving the Revolution: Italian Women's Resistance and Radicalism in New York City, 1880-1945Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Abolishing Surveillance: Digital Media Activism and State RepressionFrom EverandAbolishing Surveillance: Digital Media Activism and State RepressionNo ratings yet

- Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in BoliviaFrom EverandCoup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in BoliviaRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- For the Many: American Feminists and the Global Fight for Democratic EqualityFrom EverandFor the Many: American Feminists and the Global Fight for Democratic EqualityNo ratings yet

- Citizenship and the Origins of Women's History in the United StatesFrom EverandCitizenship and the Origins of Women's History in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Anarchist Popular Power: Dissident Labor and Armed Struggle in Uruguay, 1956–76From EverandAnarchist Popular Power: Dissident Labor and Armed Struggle in Uruguay, 1956–76No ratings yet

- Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian LeftFrom EverandLavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian LeftRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Genocide as Social Practice: Reorganizing Society under the Nazis and Argentina's Military JuntasFrom EverandGenocide as Social Practice: Reorganizing Society under the Nazis and Argentina's Military JuntasRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Redeemers: Ideas and Power in Latin AmericaFrom EverandRedeemers: Ideas and Power in Latin AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Identity and Nationalism in Modern Argentina: Defending the True NationFrom EverandIdentity and Nationalism in Modern Argentina: Defending the True NationNo ratings yet

- Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for FreedomFrom EverandSet the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for FreedomRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women's Rights and Family Values That Polarized American PoliticsFrom EverandDivided We Stand: The Battle Over Women's Rights and Family Values That Polarized American PoliticsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Meaning of Freedom: And Other Difficult DialoguesFrom EverandThe Meaning of Freedom: And Other Difficult DialoguesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Portable Postsocialisms: New Cuban Mediascapes after the End of HistoryFrom EverandPortable Postsocialisms: New Cuban Mediascapes after the End of HistoryNo ratings yet

- Women in Revolutionary Egypt: Gender and the New Geographics of IdentityFrom EverandWomen in Revolutionary Egypt: Gender and the New Geographics of IdentityNo ratings yet

- Black Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: Critical Research and PerspectivesFrom EverandBlack Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: Critical Research and PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- Creating Charismatic Bonds in Argentina: Letters to Juan and Eva PerónFrom EverandCreating Charismatic Bonds in Argentina: Letters to Juan and Eva PerónNo ratings yet

- Desired States: Sex, Gender, and Political Culture in ChileFrom EverandDesired States: Sex, Gender, and Political Culture in ChileNo ratings yet

- Assata Taught Me: State Violence, Racial Capitalism, and the Movement for Black LivesFrom EverandAssata Taught Me: State Violence, Racial Capitalism, and the Movement for Black LivesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a MovementFrom EverandFreedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a MovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (151)

- Living Quixote: Performative Activism in Contemporary Brazil and the AmericasFrom EverandLiving Quixote: Performative Activism in Contemporary Brazil and the AmericasNo ratings yet

- The Seduction of Unreason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism, Second EditionFrom EverandThe Seduction of Unreason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism, Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation MovementFrom EverandJewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation MovementRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Pan American Women: U.S. Internationalists and Revolutionary MexicoFrom EverandPan American Women: U.S. Internationalists and Revolutionary MexicoNo ratings yet

- The Women's Liberation Movement: Impacts and OutcomesFrom EverandThe Women's Liberation Movement: Impacts and OutcomesKristina SchulzNo ratings yet

- Battling Miss Bolsheviki: The Origins of Female Conservatism in the United StatesFrom EverandBattling Miss Bolsheviki: The Origins of Female Conservatism in the United StatesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Minoritarian Liberalism: A Travesti Life in a Brazilian FavelaFrom EverandMinoritarian Liberalism: A Travesti Life in a Brazilian FavelaNo ratings yet

- Cora Fdz. - Movimientos Feministas en ALDocument15 pagesCora Fdz. - Movimientos Feministas en ALAlex Guerrero RangelNo ratings yet

- Paula Biglieri, Luciana Cadahia - Seven Essays On Populism - For A Renewed Theoretical Perspective-Polity Press - John Wiley & Sons (2021)Document206 pagesPaula Biglieri, Luciana Cadahia - Seven Essays On Populism - For A Renewed Theoretical Perspective-Polity Press - John Wiley & Sons (2021)Benjamin ArditiNo ratings yet

- MAY DAY Marina&DarioDocument15 pagesMAY DAY Marina&Dariotrafalgar111No ratings yet

- Baldez-Why Women Protest - Women's Movements in Chile - Cambridge University Press (2002)Document255 pagesBaldez-Why Women Protest - Women's Movements in Chile - Cambridge University Press (2002)Ign AcioNo ratings yet

- Does Multiculturalism Menace Governance Cultural RDocument41 pagesDoes Multiculturalism Menace Governance Cultural RPaulo Víctor Sousa LimaNo ratings yet

- FOCUS GROUP DISCUSION REVEALS CHALLENGES IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCEDocument4 pagesFOCUS GROUP DISCUSION REVEALS CHALLENGES IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCECesarioVillaMartinLabajoJr.No ratings yet

- Student course classroom designation listDocument18 pagesStudent course classroom designation listLucas StadelmannNo ratings yet

- Application 11921649Document6 pagesApplication 11921649Dutch TaylorNo ratings yet

- Draft RCSP EO MunicipalDocument5 pagesDraft RCSP EO MunicipalFatimi SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Afghan Passport Application FormDocument2 pagesAfghan Passport Application FormMasihullah EbadiNo ratings yet

- The Hitler-Bormann Documents, February-April 1945Document36 pagesThe Hitler-Bormann Documents, February-April 1945api-3831252No ratings yet

- Age of ImperialismDocument4 pagesAge of Imperialismapi-263657103No ratings yet

- DPNM 2014 SCC List 08 11 14Document12 pagesDPNM 2014 SCC List 08 11 14Stephen JonesNo ratings yet

- PreambleDocument7 pagesPreambleAlfaz FirdousNo ratings yet

- The Book Thief: Do Now: Write About A Time You Stole Something (Or Wanted To)Document48 pagesThe Book Thief: Do Now: Write About A Time You Stole Something (Or Wanted To)Juliet HauptNo ratings yet

- Mass and CadreDocument30 pagesMass and CadreKaryfe Von OrtezaNo ratings yet

- Mariano V Commission On ElectionsDocument2 pagesMariano V Commission On ElectionsEdvin HitosisNo ratings yet

- PrejudiceDocument3 pagesPrejudicePoch BajamundeNo ratings yet

- Padma Bridge FinancingDocument2 pagesPadma Bridge FinancingchstuNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of Indian Society, Diversity in IndiaDocument3 pagesSalient Features of Indian Society, Diversity in IndiaVinit KuwareNo ratings yet

- Eligibility List For A Type (288 SQM Plot) : Booklet Id/ Appl. Id Name Father Name Quota Subquota Prop Type Age MobileDocument1 pageEligibility List For A Type (288 SQM Plot) : Booklet Id/ Appl. Id Name Father Name Quota Subquota Prop Type Age MobilesunuprvunlNo ratings yet

- The Ontology of Sartre Dualism and Being PDFDocument15 pagesThe Ontology of Sartre Dualism and Being PDFManolis BekrakisNo ratings yet

- Old NCERT World History Ch8Document18 pagesOld NCERT World History Ch8Mudita Malhotra75% (8)

- Example Rogerian Argument EssayDocument7 pagesExample Rogerian Argument Essaylud0b1jiwom3100% (2)

- The Tale of Two Moravian Missionaries: Ten Shekels and A ShirtDocument1 pageThe Tale of Two Moravian Missionaries: Ten Shekels and A ShirtJohn100% (1)

- Two Faces of Islam in the Western BalkansDocument15 pagesTwo Faces of Islam in the Western Balkansogulcanalkan_4811258No ratings yet

- CertificateDocument1 pageCertificateSaid NaqibNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledBOLITRES JAMICAKIMNo ratings yet

- Imre Nagy - A Biography (Communist Lives) - PDF RoomDocument285 pagesImre Nagy - A Biography (Communist Lives) - PDF RoomjNo ratings yet

- Ted ScriptDocument27 pagesTed ScriptRizka Surya AnandaNo ratings yet

- Jam Session Topics - Role of Women in SocietyDocument4 pagesJam Session Topics - Role of Women in SocietyManasa Ravali RLNo ratings yet

- WSE-LWDFS.20-08.Andik Syaifudin Zuhri-ProposalDocument12 pagesWSE-LWDFS.20-08.Andik Syaifudin Zuhri-ProposalandikszuhriNo ratings yet

- Military Recruitment Methodology 1Document469 pagesMilitary Recruitment Methodology 1Animals of the FieldsNo ratings yet

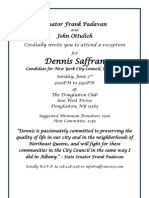

- Invitation: Reception at The Douglaston Club For Dennis Saffran For City CouncilDocument1 pageInvitation: Reception at The Douglaston Club For Dennis Saffran For City CouncilDavid ZunigaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 23 Notes SheetDocument4 pagesChapter 23 Notes SheetMary Kelly FriedmanNo ratings yet