Professional Documents

Culture Documents

US-Colombia Free Trade Agreement Labor Issues

Uploaded by

mibiquiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

US-Colombia Free Trade Agreement Labor Issues

Uploaded by

mibiquiCopyright:

Available Formats

U.S.

-Colombia Free Trade Agreement:

Labor Issues

Mary Jane Bolle

Specialist in International Trade and Finance

January 4, 2012

Congressional Research Service

7-5700

www.crs.gov

RL34759

CRS Report for Congress

Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Summary

This report examines three labor issues and arguments related to the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade

Agreement (CFTA), signed on October 21, 2011 (P.L. 112-42): violence against trade unionists;

impunity (accountability for or punishment of the perpetrators); and worker rights protections for

Colombians. For general issues relating to the CFTA, see CRS Report RL34470, The U.S.-

Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Background and Issues, by M. Angeles Villarreal. For

background on Colombia and its political situation and context for the agreement, see CRS

Report RL32250, Colombia: Issues for Congress, by June S. Beittel.

Opponents of the U.S.-Colombia free trade agreement (CFTA) argued against it on three points:

(1) the high rate of violence against trade unionists in Colombia; (2) the lack of adequate

punishment for the perpetrators of that violence; and (3) weak Colombian enforcement of

International Labor Organization (ILO) core labor standards and Colombia’s labor laws.

Proponents of the agreement argued primarily for the Colombia FTA on the basis of economic

and national security benefits. Accordingly, they argued, the CFTA would support increased

exports, expand economic growth, create jobs, and open up investment opportunities for the

United States. They also argued that it would reinforce the rule of law, spread values of capitalism

in Colombia, and anchor hemispheric stability.

Proponents specifically responded to labor complaints of the opponents, that (1) violence against

trade unionists has declined dramatically since former President Álvaro Uribe took office in

2002; (2) substantial progress is being made on the impunity issue as the government has

undertaken great efforts to find perpetrators and bring them to justice; and (3) the Colombian

government is taking steps to improve conditions for workers. The most recent steps are outlined

in the “Colombian Action Plan Related to Labor Rights,” released and jointly endorsed by

President Obama and Colombian President Juan Manual Santos, on April 7, 2011.

The Colombia FTA, along with FTAs for Panama and South Korea, are the second set of FTAs

(after Peru) to have some labor enforcement “teeth.” Labor provisions including the four basic

ILO core labor principles are enforceable through the same dispute settlement procedures as for

all other provisions (i.e., primarily those for commercial interests). Opponents argued that under

CFTA, only the concepts of core labor principles, and not the details of the ILO conventions

behind them, would be enforceable.

Proponents pointed to recent Colombian progress in protecting workers on many fronts. They

argued that approval of the FTA and the economic growth in Colombia that would result is the

best way to protect Colombia’s trade unionists. They also argued that not passing the agreement

would not resolve Colombia’s labor issues. In addition, they argued, the United States could lose

jobs through trade diversion as Colombia continues to enter into regional trade agreements with

other countries.

Opponents argued that delaying approval of the CFTA further would give Colombia more time to

keep improving protections for its workers. In fact, proponents point out, this has occurred in the

five years between 2011 when Congress approved the implementing legislation, and 2006, when

the agreement was first signed.

Congressional Research Service

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Contents

Background...................................................................................................................................... 2

Political Context ........................................................................................................................ 2

Trade/Economic Context ........................................................................................................... 2

Labor Context............................................................................................................................ 4

Violence Against Trade Unionists.................................................................................................... 4

Long-Term Trends in Homicides of Trade Unionists ................................................................ 4

Long-Term Trends in Three Measures of Violence Against Trade Unionists............................ 7

Impunity........................................................................................................................................... 8

Labor Laws, Protections, and Enforcement..................................................................................... 9

Possible Implications ..................................................................................................................... 11

Figures

Figure 1. Historic Data on Homicides of Trade Unionists, 1997-2010 ........................................... 5

Figure 2. Homicide Rate for the General Population and for Trade Unionists................................ 7

Figure 3. Assassinations, Death Threats, and Arbitrary Detentions of Trade Unionists,

1999-2010..................................................................................................................................... 8

Tables

Table A-1. Data for Figure 1: Historic Data on Homicides of Trade Unionists............................. 12

Table A-2. Data for Figure 2: Population, Homicides, and Homicide Rates for Colombia

Generally .................................................................................................................................... 13

Table A-3. Additional Data for Figure 2: Population, Homicides, and Homicide Rates for

Members of Trade Unions .......................................................................................................... 13

Table A-4. Data for Figure 3: Assassinations, Death Threats, and Arbitrary Detentions of

Trade Unionists........................................................................................................................... 14

Appendixes

Appendix. Data for Figures 1, 2, and 3.......................................................................................... 12

Contacts

Author Contact Information........................................................................................................... 14

Congressional Research Service

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

T he purpose of this report is to examine three labor issues and arguments related to the

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (CFTA): violence against trade unionists; impunity

(accountability for or punishment of the perpetrators); and worker rights protections for

Colombians.1 For general issues relating to the CFTA, see CRS Report RL34470, The U.S.-

Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Background and Issues, by M. Angeles Villarreal. For

background on Colombia and its political situation and context for the agreement, see CRS

Report RL32250, Colombia: Issues for Congress, by June S. Beittel.

Labor provisions in the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement result from a May 10, 2007,

agreement between the Administration and Congress.2 Under those provisions in the Colombia

Free Trade Agreement, (Article 17.2.1), each Party to the agreement shall “adopt and maintain in

its statutes and regulations, and practices thereunder,” five rights as stated in the International

Labor Organization (ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its

Follow-Up (1998):3

(a) freedom of association;

(b) the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining;

(c) the elimination of all forms of compulsory or forced labor;

(d) the effective abolition of child labor and for purposes of this Agreement, a prohibition

on the worst forms of child labor; and

(e) the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

Opponents of the U.S.-Colombia free trade agreement argued against it on three points: (1) the

high rate of violence (homicides, arbitrary detentions/kidnappings, and death threats) against

trade unionists in Colombia; (2) the lack of adequate punishment for the perpetrators of that

violence; and (3) weak Colombian enforcement of International Labor Organization (ILO) core

labor principles, the Conventions behind them,4 and their own labor laws.

Proponents of the agreement primarily argued for the Colombia FTA on the basis of economic

and national security benefits. Trade typically benefits all parties to a trade agreement, as each

country tends to specialize in exporting those goods which it can produce relatively more

efficiently, and to import those which it produces relatively less efficiently than its trading

partners. Accordingly, proponents argued, the CFTA will support increased exports, expand

economic growth, create U.S. jobs, offer consumers a greater variety of goods and services at

lower prices, and encourage economic development by attracting foreign investment and

1

The proposed U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (FTA) was signed on November 22, 2006. Implementing

legislation was introduced on April 8, 2008 as H.R. 5724 and S. 2830. On April 9, 2008, through H.Res. 1092 (H.Rept.

110-574) the House made certain provisions under “trade promotion authority” (otherwise known as the “fast-track”)

inapplicable to the CFTA, so that it is no longer obligated to vote within 60 days of a session and may schedule a vote

at any time. This stopped the fast-track clock. For more information on the fast-track or trade promotion process, see

CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in Trade Policy, by J. F. Hornbeck

and William H. Cooper; and CRS Report RL33864, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) Renewal: Core Labor Standards

Issues, by Mary Jane Bolle.

2

Trade Facts: Bipartisan Trade Deal, May 2007, available at http://www.ustr.gov.

3

The obligations listed refer only to the ILO Declaration, which lists the worker rights but does not reference or define

them by their detailed conventions – one each backing (a) and (b) above, and two each backing (c), (d), and (e). In

addition, to establish a violation of an obligation under Article 17.2.1, a Party must demonstrate that the other Party has

failed to adopt or maintain a statute, regulation, or practice in a manner affecting trade or investment between the

Parties.

4

Colombia has ratified all 10 of the Conventions behind the Fundamental Principles.

Congressional Research Service 1

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

expanding output. They also argued that it will reinforce the rule of law, spread values of

capitalism in Colombia, and anchor hemispheric stability.

Proponents specifically respond to the above labor complaints that (1) homicides and kidnappings

against trade unionists have declined dramatically since former President Álvaro Uribe took

office in 2002; (2) substantial progress is being made on the impunity issue as the government has

undertaken great efforts to find perpetrators and bring them to justice; and (3) the Colombian

government is taking steps to improve conditions for workers.

On April 7, 2011, the White House and the Government of Colombia, after weeks of negotiations5

released an “Action Plan Related to Labor Rights” as part of the Colombian government’s

“ongoing commitment” to prevent violence against labor leaders, prosecute the perpetrators of

such violence, and protect internationally recognized worker rights.6 For details on this Action

Plan, see CRS Report RL34470, The U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Background and

Issues, by M. Angeles Villarreal.

Background

Political Context7

Colombia is one of the oldest democracies in Latin America, and has a bicameral legislature. Yet

it has been plagued by an ongoing armed conflict for over 40 years. This violence has been

aggravated by a lack of state control over much of Colombian territory—rugged terrain that has

been hard to govern. In addition, a long history of poverty and inequality has left Colombia open

to other influences, among them drug trafficking. Leftist guerrilla groups inspired by the Cuban

Revolution formed in the 1960s as a response to state neglect and poverty. Right-wing

paramilitaries formed in the 1980s to defend landowners, many of whom were drug traffickers,

against guerrillas. The shift of coca production from Peru and Bolivia to Colombia in the 1980s

increased drug violence and provided a new source of revenue for both guerrillas and

paramilitaries. In 2002 Colombians elected an independent, Álvaro Uribe, as president (2002-

2010), largely because of his aggressive plan to reduce violence in Colombia. He was succeeded

by Jan Manuel Santos on August 7, 2010.

Trade/Economic Context

Colombia is the United States’ fourth-largest trading partner in Latin America (after Mexico,

Brazil, and Venezuela). In 2010, it was the United States’ 25th largest import source ($16 billion in

U.S. imports from Colombia) and its 20th largest export destination worldwide ($12 billion in

U.S. exports to Colombia). Machinery parts, oil, electrical machinery and organic chemicals

5

World Trade Online, U.S. Floats Detailed Labor Rights Proposal to Colombia for Vetting, April 9, 2011. See also,

House Members Send Obama Benchmarks for Colombia FTA, press release from the office of Representative Michael

Michaud, March 17, 2011

6

Colombian Action Plan Related to Labor Rights, April 7, 2011, available on USTR.gov website; and U.S., Colombia

Agree on Labor, Washington Trade Daily, April 7, 2011.

7

This section was taken from CRS Report RL32250, Colombia: Issues for Congress, by June S. Beittel.

Congressional Research Service 2

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

constituted more than half (56%) of total U.S. exports to Colombia, and mineral fuels (primarily

crude oil) accounted for 67% of all imports from Colombia.8

Given the relatively small level of trade between the United States and Colombia, (0.9% of all

U.S. trade in 2010) the CFTA would, according to a U.S. International Trade Commission

(USITC), likely have minimal to no effect on output or employment for most sectors of the U.S.

economy, because, until recently, most Colombian products already entered the U.S. market free

of duty under the Andean Trade Preference Act (ATPA).9 However, new U.S. investment in

Colombia as a result of the agreement could support increased economic growth and employment

and additional exports to the United States.

U.S. proponents argued that the proposed CFTA would provide a number of economic benefits,

including market access for U.S. consumer and industrial products; cooperation in the production

of textiles and apparel; and new opportunities for U.S. farmers and ranchers.10 With regard to the

projected small potential effect on U.S. jobs, the largest changes in U.S. output are projected for

the cereal grains production sector (0.3%) and the sugar sector (-0.3%), with similar effects on

employment. The largest changes in U.S. employment are projected to be in cereal grains (0.3%),

sugar cane (-0.3%), and textiles (-0.3%).11

Opponents argued that new U.S. investment in Colombia as a result of the agreement could

support increased economic growth and employment in Colombia and additional exports to the

United States, given the relative wage difference. U.S. total monthly compensation costs in

manufacturing for 2008 (most recent data) expressed in U.S. dollars, were roughly five times the

level of such costs in Colombia—$5,060 for the United States and $984 for Colombia.12

Colombian proponents argued that the only Western Hemisphere “Pacific Rim” countries with

which the United States did not have a free trade agreement were Colombia, Ecuador, and

Panama. Now only Ecuador remains. The United States has FTAs with all others: besides

Colombia and Panama, these are Canada, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua,

Costa Rica, Peru, and Chile.13

U.S. proponents concerned that U.S. trade with Colombia could get diverted to other countries if

the agreement were not approved, pointed out that Colombia’s current regional trade agreement

partners include the Andean Community, Chile, Mexico, Latin American countries, Canada, and

four European countries (Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland).14

8

Source: Global Trade Atlas (Census data). Colombia is the United States’ 10th most important source of these types of

fuels. Mineral fuels from Colombia account for nearly 3% of all U.S. imports of mineral fuels.

9

U.S. International Trade Commission, U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement: Potential Economy-Wide and

Selected Sectoral Effects, December, 2006, P. 2-13. The Andean Trade Preference Act, last extended under P.L. 111-

344, expired February 12, 2011.

10

Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, Colombia FTA Facts, October 2008.

11

USITC, U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement: Potential Economy-Wide and Selected Sectoral Effects, op. cit.

12

Source: Unpublished estimates compiled by Bureau of Labor Statistics, Division of International Labor Comparisons

based on data from Colombia’s Annual Survey of Manufacturing and U.S. hourly compensation data adjusted to a

comparable monthly basis. Relative compensation costs for any given year are influenced by continuing adjustment in

exchange rates.

13

Colombian Embassy, in an interview, November 20, 2008.

14

World Trade Organization Regional Trade Agreement Gateway.

Congressional Research Service 3

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Labor Context

Colombia’s official labor force is about 18.4 million, as compared with 154 million for the United

States. Roughly 23% of Colombia’s labor force is involved in the agricultural sector, 19% is

involved in the manufacturing/industry sector, and 58% is employed in the service sector. Almost

60% of the workforce in Colombia is employed in the (largely unregulated, undocumented)

informal sector. The unemployment rate in Colombia was roughly 12% in 2010. During most of

the more than 40 years that Colombia has experienced internal armed conflict, membership and

participation in labor unions has waned. Between 1959 and 1965, the unionization rate grew from

5.5% to 13.5%. Since 1966, the unionization rate has declined to 4.4% or 815,000 of the 18.4

million workforce. In 1999, roughly 1.36% of the labor force was covered by a collective

bargaining agreement. Roughly 75 percent of the workforce in Colombia’s ports is employed

under flexible non-labor contracts and consequently not allowed to join unions or bargain

collectively.15

Violence Against Trade Unionists

Long-Term Trends in Homicides of Trade Unionists

A key issue in the debate on the CFTA is the long-term trend in homicides of Colombia’s trade

unionists as they try to express rights that are in concept protected in Colombia’s laws.

Three organizations track data on the number of trade unionists murdered each year: the

Colombian government; the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), successor to the

International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU); and the Escuela Nacional Sindical

(ENS) or National Labor School, a non-governmental organization founded in 1982 in Colombia

to provide “non-partisan and independent” information on human rights, labor, and the dynamics

of association and collective bargaining. Figure 1 below tracks each of their data on the number

of homicides of trade unionists in Colombia and worldwide between 1997 and 2009. It shows a

wide year-to-year variation in the number of trade unionists murdered, but a primarily downward

trend since 2001.

Inconsistency among the three trend lines for Colombia reflects the fact that the three data

sources do not always agree on which homicides should be counted as “trade unionist.” Those

homicides that may not be counted by all sources include non-affiliated advisors to unions, retired

and inactive union members, rural and community organization members, and teachers.16

15

Data in this paragraph are from Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report Colombia, September 2010, p. 16, and

March 2011, p. 16; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; and U.S. State Department, Country Reports on Human Rights

Practices, 2009 and 2010, published March, 2010 and April 8, 2011, respectively.

16

Until recently, murders of teachers were not counted in Colombian government statistics. Yet teachers constitute the

group that has suffered the most casualties. Out of 1,994 murders in which the victim is identified by occupation

between 1986 and 2006, 825, or 41%, were teachers. Source: 2,515 or that sinister case to forget, by Guillermo Correa

Montoya, researcher for the ENS. Two researchers note that most teachers who are victims are typically singled out for

what they do outside of their classrooms as labor activists. Source: “Targeted Teachers,” by Seth Stern and Rachel Van

Dongen, Christian Science Monitor, June 17, 2003. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2008, notes that for

2008, teachers made up the largest percentage of registered unionists (34%). In part because of their presence in rural,

conflict-laden parts of the country, teachers constituted 55% of all trade unionists killed during that year.

Congressional Research Service 4

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Teachers make up the largest percentage of union members who were victims of violence by

illegal armed groups. They represent 53% of all trade unionist homicides according to Colombian

government statistics, and 56% according to ENS statistics. There are two reasons cited for this.

First, they constituted a sizable 27% of registered unionists; and second, their work situates them

in rural, conflict-ridden parts of the country.17

In Figure 1, the large bump in the homicide trend line from 1999-2003 coincides with a large

bulge in the cultivation of coca produced in Colombia and a simultaneous decline in coca

production in Bolivia and Peru, according to Department of State data. The fact that the three

lines for Colombia’s homicides of trade unionists closely track and crowd the line depicting such

homicides worldwide, shows the extent to which Colombia accounts for most such world-wide

homicides. Colombia’s share of world trade-unionist-related homicides ranges from a low of 49%

in 1999 to a high of 86% in 2002, and then declines to 54% in 2006.

Proponents argued that Colombia’s large share of the total could reflect the fact that other

countries may not document the homicides of their trade unionists as carefully as Colombia does.

Figure 1. Historic Data on Homicides of Trade Unionists, 1997-2010

Source: ICFTU/ITUC, ENS, and Colombian Government. See Appendix for data behind this graph.

Opponents of the proposed Colombia FTA tended to focus on the entire 10-plus year trend in

homicides and the close relationship between Colombia’s homicides and world-wide homicides

of trade unionists. Proponents, including the Colombian government, focused on the steady

decline in such homicides since former President Uribe took office in 2002, and on actions taken

recently by the Colombian government to reduce these fatalities. Such actions include bringing to

Colombia a permanent ILO representative, passing new labor laws, stepping up enforcement of

17

U.S. Department of State. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2010: Colombia, Worker Rights section,

April 8, 2011, p. 51 pdf version.

Congressional Research Service 5

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

labor laws, implementing a new judicial system, and setting up a trade unionist protection

program.

Under this protection program, in 2009, roughly 1,550 trade unionists were receiving

protection—14% of all persons receiving protection.18 Opponents of the Colombia FTA also point

out other reasons for the decline in homicides, including the decline in targets: Unions in

Colombia have declined from 13% of the formal labor force in 1965 to 4.4% in 2010. 19

Opponents argued that they and their efforts have been eroded primarily through such means as

violence and employer-mandated union-substitution devices such as government-sanctioned

collective pacts and cooperative associations. According to the State Department, some

economists also suggest that mandatory high nonwage benefits for vocational training and family

welfare programs depress formal employment and thus union membership, and increase informal

employment.20

Proponents of the proposed CFTA pointed out that the number of trade unionist homicides as a

share of all trade unionists is considerably smaller than the total number of homicides as a share

of the general population. For the year 2009, according to data provided by the government and

ENS, the homicide rate per 100,000 was five for unionists and 35 for the general population. (See

Figure 2.)21 The AFL-CIO countered that “it is simply not meaningful to compare random crime

statistics to targeted assassinations.”22

18

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2009: Colombia, Worker Rights section, March 11, 2010.

19

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2010: Colombia, Worker Rights section, April 8, 2011, p. 50.

20

Ibid., p. 53.

21

U.S. Department of State: 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Colombia. March 11, 2010.

22

AFL-CIO. Colombia: Continued Violence, Impunity and Non-Enforcement of Labor Law Overshadow the

Government’s Minor Accomplishments, September 2008, Update.

Congressional Research Service 6

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Figure 2. Homicide Rate for the General Population and for Trade Unionists

Source: See Appendix data tables for Figure 2.

Long-Term Trends in Three Measures of Violence Against

Trade Unionists

A companion issue to trade unionist homicides is long-term trends in three separate measures of

trade union violence: homicides/assassinations, kidnappings/arbitrary detentions, and death

threats.

Proponents of the CFTA noted reductions in assassinations and arbitrary detentions since 2004.

Opponents, examining the data longer term, focused on a third means of intimidation: death

threats. They argued that in recent years perpetrators have switched their focus from homicides to

death threats, because this more subtle form of intimidation can achieve the same results of

discouraging union activity with less public notice.23 These three methods of intimidation are

tracked individually in the left graph in Figure 3 and cumulatively in the right graph. The right

graph shows that assassinations/homicides were about equal to death threats in 2001-2002 when

homicides were at their peak, but averaged less than one-quarter the number of death threats

between 2003 and 2009, when homicides were lower.

23

Speech by José Luciano Sanín Vásquez, Director General of the ENS, sponsored by the Global Policy Network,

February 27, 2008.

Congressional Research Service 7

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Figure 3. Assassinations, Death Threats, and Arbitrary Detentions of

Trade Unionists, 1999-2010

Source: See Appendix data table for Figure 3.

Impunity

The second main issue of opponents in debating CFTA is impunity—accountability for and

punishment of the perpetrators of assassinations, arbitrary detentions, and death threats.

Perpetrators of the violence typically fall into three main groups: paramilitaries, guerrillas, and

the Colombian military.24 The human rights advocates group Amnesty International USA has

reported on the difficulty in identifying the perpetrators in cases of trade union violence.

However, it reported that, among “cases in which clear evidence of responsibility is available” in

2005, of all human rights abuses against trade unionists: paramilitaries committed 49%; security

forces committed 43%; guerrilla forces committed 2%; and criminals committed 4%.25

Proponents of the agreement cite data showing progress in bringing perpetrators of the violence to

justice: as the result of a tripartite agreement with the ILO (among the government, trade

confederations, and business groups), the Office of the Colombian Prosecutor General, in October

2006, created a special sub-unit to investigate and prosecute 1,272 criminal cases of violence

against trade union members. These included 187 priority cases as determined by the unions.26

24

U.S. State Department, Charting Colombia’s Progress, October 12, 2007.

25

Amnesty International USA, Colombia Killings, Arbitrary Detentions, and Death Threats—the Reality of Trade

Unionism in Colombia, Introduction, 2007. ENS data.

26

On June 12, 2008, three union confederations, CUT, CGT, and CTC, submitted to the ILO a list of 2,669 homicides

and forced disappearance cases as part of case 1787. According to the government of Colombia, the Ministry of Social

Protection is now cross-referencing this new case list with its existing case list.

Congressional Research Service 8

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

As of February 20, 2010, there were a total of 248 convictions in cases involving violence against

trade union members between 2001 and the first two months of 2010, with 199 (80%) of them

handed down in 2007-2010. These 248 conviction cases resulted in the conviction of 350

individuals, including 216 imprisonments.27 José Luciano Sanín Vásquez, Director General of the

ENS views convictions over a longer period of time and points out that since 1986, in about 97%

of the cases of homicides of trade unionists, the perpetrators have never been identified and

brought to justice. He argued further that while in some cases the perpetrators of labor killings are

found guilty, in zero cases has the mastermind behind the crime been convicted.28

In September 2009, the AFL-CIO, in a submission to the USTR, laid out detailed labor and

human rights conditions it wanted Colombia to meet before the United States would consider

approving the CFTA. These included (1) convictions in a substantial majority of the over 2,700

cases of trade unionists murdered and prosecutions against both those responsible for carrying out

the crimes and those planning the crimes; and (2) the undertaking of substantial efforts to

investigate non-lethal forms of violence, including death threats.29

Labor Laws, Protections, and Enforcement

A third main issue in the CFTA is adequacy of enforcement of Colombia’s labor laws, and

Colombia’s ability to protect workers. Many observers point out that enforcement of labor laws

and standards generally is an issue for Colombia as well as throughout Latin America and other

developing countries.

Proponents pointed to Colombia’s system of labor laws and protections, which includes

ratification of all four ILO core labor standards30—that is, ratification of both the ILO core labor

principles and the detailed Conventions that define them. The ILO core labor principles: (1)

protect the right of workers to organize and bargain collectively, (2) prohibit forced labor, (3)

prohibit child labor, and (4) provide for nondiscrimination in employment.

Others point to strengths and weaknesses in Colombia’s protection of worker rights, as reported

in the State Department’s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices.31 Some key

findings from its 2011 report for Colombia are as follows:

27

Fiscalia, February 20, 2010. It should be noted that, according to the statistical branch of the Colombian government,

in a significant number of the cases, the defendant was convicted in absentia and is not currently in custody. Therefore,

currently, about two-thirds of those convicted are serving time in prison.

28

Speech by José Luciano Sanín Vásquez, op. cit., with updated figures from the Colombian government. As of July of

2009, an AFL-CIO submission to the USTR notes 154 convictions in cases involving violence between 2001 and 2008,

with most of them handed down in 2007-2008. The AFL-CIO Submission notes that a March 2009 report by Fiscalia

(Colombia’s Office of the Attorney General) claims that 33 “intellectual authors” of the crimes had been sentenced.

However, a subsequent July 20, 2009 report included no information on intellectual authors. Source: AFL-CIO. Before

the U.S. Trade Representative, Comments Concerning the Pending Free Trade Agreement with Colombia. Filed

September 15, 2009, p. 4.

29

Ibid., p. 5-6.

30

Office of the USTR. Colombia FTA Facts. Colombia’s Labor Laws and Labor Protections. March 2008.

31

U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2010, April 8, 2011. Included in the annual

reports on more than 100 countries, is a section on their adherence to U.S. internationally recognized worker rights

principles. This list of principles, codified in the U.S. Trade Act of 1974, (P.L. 93-618 as amended), is similar to the

ILO list, but includes the “right of association” in addition to the “right to organize and bargain collectively,” and

(continued...)

Congressional Research Service 9

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

• Right to Organize and Bargain Collectively. In general, Colombian law allows

some workers to form unions, and the government generally respected this right

in practice. However, there exist a number of legal restrictions to forming and

joining a union, particularly in indirect contracting situations. These restrictions

stem from the fact that Colombia’s labor laws define a “worker” as a direct hire

with an employment contract. Thus, workers in three groups have at times been

treated—legally or illegally—as indirect hires, and thus not covered by

Colombia’s labor code: those employed under (1) workers’ cooperatives, (2)

temporary service agencies for seasonal, temporary, and contract workers, and (3)

collective pacts. The report also notes that some unions have been formed despite

some legal restrictions. It also notes that unionists continue to advocate for

revision to the labor code. In addition, the report notes that collective bargaining

has not been fully implemented in the public sector.

• Prohibition of Forced or Compulsory Labor. The law prohibits forced or

compulsory labor, including by children, but there were some reports that such

practices occurred. New illegal armed groups, which included some former

paramilitary members and guerrillas, reportedly used forced labor in coca

cultivation in areas outside government control. Forced labor which included

organized begging and forced commercial sexual exploitation, often of internally

trafficked women and children, reportedly remained a serious problem.

• Prohibition of Child Labor and Minimum Wage for Employment. While

there are laws to protect children from exploitation in the workplace, child labor

reportedly remained a problem in the informal and illicit sectors. Mentioned as

significant incidences in which child labor was used, included in the production

of clay bricks, coal, emeralds, gold, coca, and pornography, often under

dangerous conditions and in many instances with the approval and/or insistence

of their parents.

• Acceptable Conditions of Work. The government establishes a uniform

minimum wage every January. The monthly minimum wage for 2010 was

reportedly $285, a 3.6% increase over the previous year. According to the report,

the national minimum wage did not provide a decent standard living for a worker

and family. In addition the government reportedly remained unable to enforce the

minimum wage in the informal sector. The law provides protection for workers’

occupational safety and health in the formal sector, which the government

enforced through periodic inspections. However, the report notes, a scarcity of

government inspectors, poor safety awareness, and inadequate attention by

unions resulted in a high level of industrial accidents and unhealthy working

conditions in the formal sector.

(...continued)

substitutes “acceptable conditions of work” relating to minimum wages, hours of work, and occupational safety and

health, for the ILO’s “nondiscrimination in employment” principle.

Congressional Research Service 10

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Possible Implications

The Colombia FTA (along with Panama and South Korea) is in the second set of FTAs (after

Peru) to have some labor enforcement “teeth.” Labor provisions including the four basic ILO core

labor principles (enumerated previously) would be enforceable through the same dispute

settlement procedures as for all other provisions, such a those for commercial interests.

Opponents argued that under the CFTA, only the concepts of core labor principles, and not the

details of the ILO Conventions behind them, would be enforceable.

Proponents pointed to recent Colombian progress in protecting workers on many fronts. First, the

personal protection program for union members has been a success in that since 2002, not a

single trade union member enrolled in the program has been killed, according to the Colombian

Embassy.32 Second, funding for investigating and prosecuting perpetrators of crimes against trade

unionists has increased. Third, the government has engaged in greater social dialogue with the

ILO and other international union organizations, which are having an impact on national labor

policy. Fourth, other legislative approaches have been proposed to further protect basic core labor

rights.33 Fifth, the “Action Plan Related to Labor Rights,” jointly released by the President Obama

and Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos on April 7, 2011, is designed to “address serious

and immediate labor concerns” and to “lead to greatly enhanced labor rights in Colombia and

clear the way for the U.S.-Colombia Trade Agreement to more forward in Congress.”34

Opponents argued that delaying the vote on the CFTA further would give Colombia more time to

keep improving protections for its workers. They asserted that Colombia is still the most

dangerous place in the world to be a trade unionist, since it still accounts for the majority of

homicides of trade unionists world-wide. They also argued that the progress made in bringing to

justice perpetrators of violence against union workers has been limited, and point to the fact that a

significant percentage of those convicted in these cases are convicted in absentia and remain at

large. Finally, they argued that passing the CFTA could very well halt the progress by the

Colombian government on worker rights protections achieved to date.35

Proponents argued that the window of opportunity to pass the CFTA may be relatively narrow,

and that approval of the FTA and the economic growth in Colombia that would result is the best

way to protect Colombia’s trade unionists. They also argued that not passing the agreement would

not resolve Colombia’s labor issues.

Passage of the Colombia FTA implementing legislation on October 21, 2011 (P.L. 112-42), opens

up a new lens through which to observe Colombia’s progress relating to labor rights.

32

As of 2010, there were 1,442 trade unionists in the protection program (14% of 10,510 under protection) according to

the Ministry of the Interior, as reported in Protecting Labor and Ensuring Justice in Colombia, Embassy of Colombia,

January, 2011.

33

An Open Letter to Congressional Democrats on Hemispheric Trade Expansion. Signed by seven former Members of

Congress and the Senate and at least 30 former cabinet officials, ambassadors, and foreign and trade policy advisors.

Available at http://www.chamberpost.com/files/Colombia_Letter_from_Former_Democratic_Officials.pdf. (Undated.)

34

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Fact Sheets: U.S.-Colombia Trade Agreement and Action Plan,

April 6, 2011; and Colombian Action Plan Related to Labor Rights, April 7, 2011.

35

Various sources already identified plus USLEAP, Violence Against Colombia Trade Unionists and Impunity: How

Much Progress Has There Been Under Uribe? April 2008.

Congressional Research Service 11

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Appendix. Data for Figures 1, 2, and 3

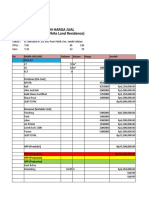

Table A-1. Data for Figure 1: Historic Data on Homicides of Trade Unionists

Year World-Wide Colombia

Colombian

ICFTU/ITUC ICFTU/ITUC ENS Government

1997 299 170

1998 157 97

1999 140 69 82

2000 210 153 134 155

2001 223 185 194 205

2002 213 154 192 196

2003 129 90 102 101

2004 145 99 94 89

2005 115 70 72 40

2006 144 78 76 60

2007 130 39 39 26

2008 76 49 49 39

2009 101 48 47 28

2010 NA NA 51 34

Source: ICFTU/ITUC: Annual Survey of Violations of Trade Union Rights, various years; ENS: Situation of Violence

and Impunity, 1986-2010; Colombian Government: U.S. State Department. For 2009: Memorandum of

Justification Concerning Human Rights Conditions With Respect to Assistance for the Colombian Armed Forces;

for 2010, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2010: Colombia, Section 7. April 8, 2011.

Congressional Research Service 12

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Table A-2. Data for Figure 2: Population, Homicides, and Homicide Rates for

Colombia Generally

General Population Number of Homicides Homicide Rate per

Year (millions) (thousands) 100,000

1997 40.0 25 63

1998 40.7 23 56

1999 41.4 24 59

2000 42.1 27 63

2001 42.8 28 65

2002 43.5 29 66

2003 44.2 24 53

2004 44.9 20 45

2005 43.7 18 39

2006 44.4 17 37

2007 45 17 36

2008 45.7 16 33

2009 46.3 16 34

Source and methods: Data for general population: IMF International Financial Statistics; for homicides:

Colombia ministry of Defense and Colombian Embassy.

Table A-3. Additional Data for Figure 2: Population, Homicides, and Homicide Rates

for Members of Trade Unions

Number Number of

Members Number of of Homicides

of Trade Homicides Homicide Homicides Homicide (Colombian Homicide

Unions (ICFTU/ITUC Rate per (ENS Rate per Government Rate per

Year (000) data) 100,000 data) 100,000 data) 100,000

1997 1,054 NA NA 170 16 NA NA

1998 NA NA NA 97 NA NA NA

1999 NA 69 NA 82 NA NA NA

2000 NA 153 NA 134 NA 105 NA

2001 860 185 22 194 23 205 24

2002 NA 154 NA 192 NA 196 NA

2003 856 90 11 102 12 101 12

2004 856 99 12 94 11 89 10

2005 900 70 8 72 8 40 4

2006 830 78 9 76 9 60 7

2007 NA 39 NA 39 NA 26 NA

Congressional Research Service 13

U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Labor Issues

Number Number of

Members Number of of Homicides

of Trade Homicides Homicide Homicides Homicide (Colombian Homicide

Unions (ICFTU/ITUC Rate per (ENS Rate per Government Rate per

Year (000) data) 100,000 data) 100,000 data) 100,000

2008 NA 49 NA 49 NA 38 NA

2009 815 48 6 47 6 28 3

2010 NA NA NA 51 NA 34 NA

Source and Methods: Data on number of members in trade unions: ENS data as reported in the State

Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, various years.

Table A-4. Data for Figure 3: Assassinations, Death Threats, and

Arbitrary Detentions of Trade Unionists

Year Assassinations Arbitrary Detentions Death Threats

1999 80 29 679

2000 137 38 180

2001 197 12 235

2002 186 13 198

2003 94 50 301

2004 96 79 455

2005 70 56 260

2006 72 16 244

2007 39 19 224

2008 49 26 497

2009 47 34 412

2010 51 3 306

Source: Escuela Nacional Sindical, 2,515 or that sinister ease to forget, 2008, p. 69 Updated for 2007-2009. Data

for 2010 are from the State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2010, April 8, 2011.

Author Contact Information

Mary Jane Bolle

Specialist in International Trade and Finance

mjbolle@crs.loc.gov, 7-7753

Congressional Research Service 14

You might also like

- US-Colombia Free Trade Agreement BackgroundDocument31 pagesUS-Colombia Free Trade Agreement BackgroundmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Ensayo Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument6 pagesEnsayo Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Advantages and DisadvantagesAlejandra VillalbaNo ratings yet

- Evidencianensayo 2762fb25da5b23dDocument15 pagesEvidencianensayo 2762fb25da5b23dleidy jhoannaNo ratings yet

- Treaties of Free Trade Between Colombia and The United StatesDocument3 pagesTreaties of Free Trade Between Colombia and The United StatesHelen LpoezNo ratings yet

- Actividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (Fta) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document5 pagesActividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (Fta) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Andreita PinzonNo ratings yet

- Actividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3Document5 pagesActividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3Karen JaliscoNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (Fta) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document8 pagesEvidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (Fta) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Juliana GrNo ratings yet

- EVIDENCIA 3 Ensayo IngDocument7 pagesEVIDENCIA 3 Ensayo Ingmartha liliana sanchezNo ratings yet

- FTA Between Colombia and US: Advantages Like Wider Markets and Access to Quality Goods at Lower Prices, Disadvantages Such as Difficulty CompetingDocument6 pagesFTA Between Colombia and US: Advantages Like Wider Markets and Access to Quality Goods at Lower Prices, Disadvantages Such as Difficulty CompetingCristinaNo ratings yet

- FTAs Colombia-US: Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument4 pagesFTAs Colombia-US: Advantages and DisadvantagesLina Marcela Molina CastañedaNo ratings yet

- FTA Colombia US advantages disadvantages essayDocument6 pagesFTA Colombia US advantages disadvantages essayerikaNo ratings yet

- Actividad de Aprendizaje 11: Jean Carlos Vargas MartínezDocument4 pagesActividad de Aprendizaje 11: Jean Carlos Vargas MartínezJuan Carlos Vargas MartinezNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity 11 Evidence Number 3Document8 pagesLearning Activity 11 Evidence Number 3Peña AndrésNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument4 pagesEvidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and Disadvantagesmiguel angel ruedaNo ratings yet

- FTA Advantages and Disadvantages for ColombiaDocument6 pagesFTA Advantages and Disadvantages for ColombiaAnna RamosNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document5 pagesEvidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"rosaNo ratings yet

- Free Trade Agreement between Colombia and US: Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument6 pagesFree Trade Agreement between Colombia and US: Advantages and DisadvantagesDawinNo ratings yet

- EV03 Ensayo FreeTradeAgreementDocument7 pagesEV03 Ensayo FreeTradeAgreementLuis Fernando CastilloNo ratings yet

- Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document5 pagesEnsayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Nora SánchezNo ratings yet

- Actividad de Aprendizaje 11Document7 pagesActividad de Aprendizaje 11Heryi ScarpetaNo ratings yet

- Actividad de Aprendizaje #11Document5 pagesActividad de Aprendizaje #11Rubén Darío Gutiérrez PiedrahítaNo ratings yet

- Essay Free Trade Agrement FTA - Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument5 pagesEssay Free Trade Agrement FTA - Advantages and DisadvantagesFabian Leonardo Rodriguez Neira0% (1)

- Broken Promises: Decades of Failure to Enforce Labor Standards in Free Trade AgreementsDocument16 pagesBroken Promises: Decades of Failure to Enforce Labor Standards in Free Trade AgreementsKevinO'DonnellNo ratings yet

- Ok Actividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3Document5 pagesOk Actividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3Andres RodriguezNo ratings yet

- FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument6 pagesFTA Advantages and DisadvantagesWilmer PrietoNo ratings yet

- International Negotiation EssayDocument4 pagesInternational Negotiation Essayjack zadmanNo ratings yet

- Ensayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument3 pagesEnsayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesCristian ParraNo ratings yet

- FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument5 pagesFTA Advantages and DisadvantagesjoseNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 11Document3 pagesEvidencia 11Beberly ElguedoNo ratings yet

- Investigue Sobre Los Tratados de Libre Comercio Que Colombia Tiene Vigentes Con Los Estados UnidosDocument3 pagesInvestigue Sobre Los Tratados de Libre Comercio Que Colombia Tiene Vigentes Con Los Estados Unidososvaldo1utria1jimeneNo ratings yet

- Ev3 Free Trade Agreement FTADocument8 pagesEv3 Free Trade Agreement FTATatiana VelascoNo ratings yet

- AA11 - Evidencia 3 - Ensayo Free Trade Agreement Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument3 pagesAA11 - Evidencia 3 - Ensayo Free Trade Agreement Advantages and DisadvantagesOscar ToroNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument3 pagesEvidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Advantages and DisadvantagesNelson Andres Abril Zapata88% (8)

- 2 Tratado de Libre ComercioDocument4 pages2 Tratado de Libre ComercioIvan RodriguezNo ratings yet

- AA 11 Evidencia 3 - Leidy J. Murillo CDocument5 pagesAA 11 Evidencia 3 - Leidy J. Murillo CLeidy MurilloNo ratings yet

- FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument6 pagesFTA Advantages and DisadvantagesSharon CastroNo ratings yet

- Beyond Pre-Reconstruction Slavery America's Modern Day Trade Practices and Confront Forced LabourDocument27 pagesBeyond Pre-Reconstruction Slavery America's Modern Day Trade Practices and Confront Forced LabourHuyen NguyenNo ratings yet

- FTA Advantages And Disadvantages Between Colombia And USDocument3 pagesFTA Advantages And Disadvantages Between Colombia And USYurany Cano OlarteNo ratings yet

- 17874-Article Text-24905-1-10-20140819Document68 pages17874-Article Text-24905-1-10-20140819Xin HuiNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreemen ZT (FTA) Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument5 pagesEvidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreemen ZT (FTA) Advantages and DisadvantagesFamilia Peña GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages "Document4 pagesEvidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages "jpp soluciones y servicios integrales sasNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 11.3 DairoDocument5 pagesEvidencia 11.3 DairoDairo SaldarriagaNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document4 pagesEvidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Javier CespedesNo ratings yet

- Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (Fta) "Document5 pagesEnsayo "Free Trade Agreement (Fta) "Moisés Vega GuzmánNo ratings yet

- Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document4 pagesEnsayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Julian AcevedoNo ratings yet

- The Pending Trade Agreement With Colombia: HearingDocument190 pagesThe Pending Trade Agreement With Colombia: HearingScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3Document6 pagesEvidencia 3GUSTAVO ADRIAN HINCAPIE DUQUENo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument4 pagesEvidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesLuis BallesterosNo ratings yet

- WTo and ILODocument35 pagesWTo and ILOpravinsankalpNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument5 pagesEvidencia 3 Ensayo Free Trade Agreement FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesHervin JimenezNo ratings yet

- FTAs disadvantages essayDocument2 pagesFTAs disadvantages essayDaniel MonteroNo ratings yet

- FTA Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument6 pagesFTA Advantages and DisadvantagesMaribel carranza caleñoNo ratings yet

- Article 37: Torture and Deprivation of LibertyDocument45 pagesArticle 37: Torture and Deprivation of LibertynucauribeNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document4 pagesEvidencia 3: Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"jesus david franco barriosNo ratings yet

- Tecnologo en Negociacion Internacional: Francisco Javier Arias OsorioDocument5 pagesTecnologo en Negociacion Internacional: Francisco Javier Arias Osoriojhon acostaNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3 Act 11 IngDocument7 pagesEvidencia 3 Act 11 IngJohanita GomezNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 3. Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Advantages and Disadvantages"Document6 pagesEvidencia 3. Ensayo "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Advantages and Disadvantages"DANIA MELISSA RAMIREZ LOANGONo ratings yet

- Actividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3: "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Document3 pagesActividad de Aprendizaje 11 Evidencia 3: "Free Trade Agreement (FTA) : Advantages and Disadvantages"Saritha CardenasNo ratings yet

- The Southern J of Philosophy - 2021 - Emmanuel - Defending The Decolonization Trope in Philosophy A Reply To Ol F Mi T WDocument16 pagesThe Southern J of Philosophy - 2021 - Emmanuel - Defending The Decolonization Trope in Philosophy A Reply To Ol F Mi T WmibiquiNo ratings yet

- El Espectador Michael Evans INterview (English)Document11 pagesEl Espectador Michael Evans INterview (English)mibiquiNo ratings yet

- The Negritude Movements in Colombia PDFDocument351 pagesThe Negritude Movements in Colombia PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Remote WarfareDocument22 pagesRemote WarfaremibiquiNo ratings yet

- BPP Ten Point ProgramDocument3 pagesBPP Ten Point Programapi-347356811No ratings yet

- The Anthropocene and Music Studies - Ethnomusicology Review PDFDocument13 pagesThe Anthropocene and Music Studies - Ethnomusicology Review PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Decolonizing Time Through Dance With Kwenda Lima Cabo Verde Creolization and Affiliative Afromodernity PDFDocument17 pagesDecolonizing Time Through Dance With Kwenda Lima Cabo Verde Creolization and Affiliative Afromodernity PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- B The L) Ancing Couple in Black Atlantic Space: Ananya Jahanara KabirDocument10 pagesB The L) Ancing Couple in Black Atlantic Space: Ananya Jahanara KabirmibiquiNo ratings yet

- The Dialectics of Twoness in Yoruba Art and CultureDocument17 pagesThe Dialectics of Twoness in Yoruba Art and Culturemibiqui100% (1)

- Oceans Cities Islands PDFDocument20 pagesOceans Cities Islands PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Dance and Decolonisation in Africa Introduction PDFDocument5 pagesDance and Decolonisation in Africa Introduction PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Fétichisme Et Féticheurs PDFDocument127 pagesFétichisme Et Féticheurs PDFmibiqui100% (2)

- Meaning Beyond Words - A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumm PDFDocument180 pagesMeaning Beyond Words - A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumm PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Imagination Sensation and The Education PDFDocument22 pagesImagination Sensation and The Education PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Did Ogboni Exist in Old Oyo? PDFDocument9 pagesDid Ogboni Exist in Old Oyo? PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Theory For Ethnomusicology Histories, Conversations, Insights PDFDocument255 pagesTheory For Ethnomusicology Histories, Conversations, Insights PDFmibiqui100% (3)

- Position of Artist in Trad. Society PDFDocument12 pagesPosition of Artist in Trad. Society PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Attitude of Educated African To His Art PDFDocument5 pagesAttitude of Educated African To His Art PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Attitude of Educated African To His Art PDFDocument5 pagesAttitude of Educated African To His Art PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- The Use of Plants in Yoruba SocietyDocument17 pagesThe Use of Plants in Yoruba Societymibiqui100% (3)

- The Dialectics of Twoness in Yoruba Art and CultureDocument17 pagesThe Dialectics of Twoness in Yoruba Art and Culturemibiqui100% (1)

- Position of Artist in Trad. Society PDFDocument12 pagesPosition of Artist in Trad. Society PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- 19th C. Origins of Nigerian NationalismDocument16 pages19th C. Origins of Nigerian NationalismmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Conceptions of Death PDFDocument14 pagesConceptions of Death PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- The Dialectics of Twoness in Yoruba Art and CultureDocument17 pagesThe Dialectics of Twoness in Yoruba Art and Culturemibiqui100% (1)

- MLK-The Dilemma of Negro AmericansDocument18 pagesMLK-The Dilemma of Negro AmericansmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Conceptions of Death PDFDocument14 pagesConceptions of Death PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- Ancient Ife-A Reassessment PDFDocument82 pagesAncient Ife-A Reassessment PDFmibiquiNo ratings yet

- GST Notes-CA Inter-May 23 1 Lyst8910 PDFDocument172 pagesGST Notes-CA Inter-May 23 1 Lyst8910 PDFMaheshkumar PerlaNo ratings yet

- Attendance - Inst1 - Batch 1 & 2 (Oct.4,2021-DSF)Document2 pagesAttendance - Inst1 - Batch 1 & 2 (Oct.4,2021-DSF)Aljay LabugaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating a New Sugarcane Peeling Machine PrototypeDocument10 pagesEvaluating a New Sugarcane Peeling Machine PrototypeOdior EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Ciri Intrinsik Novel Populer Indonesia Yang Terbit Tahun 1980-AnDocument11 pagesCiri Intrinsik Novel Populer Indonesia Yang Terbit Tahun 1980-AnTeguh Firman SNo ratings yet

- Latent View Analytics IPO Date, Price, GMP, DetaiDocument2 pagesLatent View Analytics IPO Date, Price, GMP, DetaiArvind ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Abm TermsDocument2 pagesAbm TermsAxeliaNo ratings yet

- U4A1 AssignmentDocument1 pageU4A1 AssignmentDrippy SnowflakeNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting ProjectDocument12 pagesFinancial Accounting ProjectRishabh ManawatNo ratings yet

- Deed of Conditional Sale AgreementDocument2 pagesDeed of Conditional Sale Agreementjan l.No ratings yet

- Vietnam Logistics Industry RealityDocument10 pagesVietnam Logistics Industry RealityQuỳnh GiaoNo ratings yet

- Toyota VS HondaDocument70 pagesToyota VS Hondaappkamubashar7364100% (5)

- Service Operations ManagementDocument68 pagesService Operations ManagementAnushka KanaujiaNo ratings yet

- Accounting of DepreciationDocument9 pagesAccounting of DepreciationPrasad BhanageNo ratings yet

- Maf 5101 Financial AccountingDocument2 pagesMaf 5101 Financial AccountingertaudNo ratings yet

- Analisis SWOT Pemasaran Produk Kerupuk Buah Di UD. Sukma Kecamatan Takisung Kabupaten Tanah LautDocument11 pagesAnalisis SWOT Pemasaran Produk Kerupuk Buah Di UD. Sukma Kecamatan Takisung Kabupaten Tanah Lautrohmatul sahriNo ratings yet

- Lesson 7 - Laboratory BudgetDocument27 pagesLesson 7 - Laboratory BudgetFranzil Shannen PastorNo ratings yet

- Exploring-Strategies-and-Challenges-in-Weekly-Allowance-Budgeting-among-1st-year-and-2nd-year-College-Students-at-Caraga-State-University-Cabadbaran-Campus-focuses-on-understanding-the-strategies-emp-1Document17 pagesExploring-Strategies-and-Challenges-in-Weekly-Allowance-Budgeting-among-1st-year-and-2nd-year-College-Students-at-Caraga-State-University-Cabadbaran-Campus-focuses-on-understanding-the-strategies-emp-1Geralyn RefugioNo ratings yet

- KIA SELTOS BookingDocketDocument7 pagesKIA SELTOS BookingDocketNeelNo ratings yet

- Estimasi Perhitungan Harga Jual Perumahan WLR 2Document25 pagesEstimasi Perhitungan Harga Jual Perumahan WLR 2Next LevelManagementNo ratings yet

- compagnie-de-la-baie-de-st-augustin-v-cornelius-finance-co-ltd-and-ors-2011-scj-1120160529032930912_1Document16 pagescompagnie-de-la-baie-de-st-augustin-v-cornelius-finance-co-ltd-and-ors-2011-scj-1120160529032930912_1toshanperyagh1No ratings yet

- International Package Services Invoice SummaryDocument12 pagesInternational Package Services Invoice SummaryBingmondoy Feln Lily Canonigo0% (1)

- Retail Industry Comps Template: Strictly ConfidentialDocument6 pagesRetail Industry Comps Template: Strictly Confidentialsh munnaNo ratings yet

- MFSA Annual Report 2006Document52 pagesMFSA Annual Report 2006cikkuNo ratings yet

- Development of Modern Economics: Created by Egor ArtiukhDocument6 pagesDevelopment of Modern Economics: Created by Egor ArtiukhВова УрсуловNo ratings yet

- How Jack Welch Runs GE: The Legendary CEO's Leadership SecretsDocument25 pagesHow Jack Welch Runs GE: The Legendary CEO's Leadership SecretsAndre Luiz Martins RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Mutual FundDocument43 pagesMutual FundSachi LunechiyaNo ratings yet

- Deloitte Localisation in Africas Oil & Gas Industry Oct 2015Document18 pagesDeloitte Localisation in Africas Oil & Gas Industry Oct 2015Jim BabanNo ratings yet

- Scientific ManagementDocument24 pagesScientific Managementdipti30No ratings yet

- ECO 303 PQsDocument21 pagesECO 303 PQsoyekanolalekan028284No ratings yet

- BBMF 2093 Corporate Finance: Characteristic Line (SML) Slope of The Line To Be 1.67Document6 pagesBBMF 2093 Corporate Finance: Characteristic Line (SML) Slope of The Line To Be 1.67WONG ZI QINGNo ratings yet

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarFrom EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaFrom EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerFrom EverandThe Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (47)

- How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the PentagonFrom EverandHow Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything: Tales from the PentagonRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- Conflict: The Evolution of Warfare from 1945 to UkraineFrom EverandConflict: The Evolution of Warfare from 1945 to UkraineRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against FateFrom EverandThe Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against FateRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (93)

- Cry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskFrom EverandCry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear WarFrom EverandThe Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- The Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerFrom EverandThe Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- War and Peace: FDR's Final Odyssey: D-Day to Yalta, 1943–1945From EverandWar and Peace: FDR's Final Odyssey: D-Day to Yalta, 1943–1945Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Generals Have No Clothes: The Untold Story of Our Endless WarsFrom EverandThe Generals Have No Clothes: The Untold Story of Our Endless WarsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Prompt and Utter Destruction, Third Edition: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against JapanFrom EverandPrompt and Utter Destruction, Third Edition: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against JapanRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Three Cups of Tea: One Man's Mission to Promote Peace . . . One School at a TimeFrom EverandThree Cups of Tea: One Man's Mission to Promote Peace . . . One School at a TimeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3422)

- The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyFrom EverandThe Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign PolicyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Catch-67: The Left, the Right, and the Legacy of the Six-Day WarFrom EverandCatch-67: The Left, the Right, and the Legacy of the Six-Day WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- Eating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani BombFrom EverandEating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani BombRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Perfect Weapon: war, sabotage, and fear in the cyber ageFrom EverandThe Perfect Weapon: war, sabotage, and fear in the cyber ageRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)

- How the West Brought War to Ukraine: Understanding How U.S. and NATO Policies Led to Crisis, War, and the Risk of Nuclear CatastropheFrom EverandHow the West Brought War to Ukraine: Understanding How U.S. and NATO Policies Led to Crisis, War, and the Risk of Nuclear CatastropheRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (16)

- The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central AsiaFrom EverandThe Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central AsiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (406)

- The Age of Walls: How Barriers Between Nations Are Changing Our WorldFrom EverandThe Age of Walls: How Barriers Between Nations Are Changing Our WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (55)

- The Shadow Commander: Soleimani, the US, and Iran's Global AmbitionsFrom EverandThe Shadow Commander: Soleimani, the US, and Iran's Global AmbitionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?From EverandDestined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (50)

- Mossad: The Greatest Missions of the Israeli Secret ServiceFrom EverandMossad: The Greatest Missions of the Israeli Secret ServiceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (84)