Professional Documents

Culture Documents

cureus 0011 00000005819 ١

Uploaded by

DrAbdullah HajarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

cureus 0011 00000005819 ١

Uploaded by

DrAbdullah HajarCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Case

Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.5819

Giant Cell Tumor with Secondary

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst of the Patella: A

Case Report

Sujit K. Tripathy 1 , Sunil Doki Dr 1 , Gayatri Behera 2 , Mukund Sable 2

1. Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, IND 2. Pathology, All India

Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, IND

Corresponding author: Sujit K. Tripathy, sujitortho@yahoo.co.in

Disclosures can be found in Additional Information at the end of the article

Abstract

A 15-year-old girl presented with pain and swelling on the anterior aspect of the right knee for

one year. The radiological evaluation with x-rays and magnetic resonance imaging suggested a

benign aggressive lesion of the right patella with a cortical breach. Core needle biopsy of the

lesion revealed it to be a giant cell tumor (GCT). She was treated with total patellectomy and

end-to-end repair of quadriceps to the patellar tendon. The histopathological report of the

whole specimen revealed it to be a GCT with secondary aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC). After 24

months, she was asymptomatic, and there was no evidence of local recurrence or distal

metastasis. An extensive review of the literature revealed only four cases of combined GCT with

secondary ABC in the patella. Though rare, GCT with secondary ABC of the patella should be

kept as a differential diagnosis for anterior knee pain and swelling in young patients. The

diagnosis is solely based on histopathological findings. It is imperative to obtain a precise

tissue diagnosis in the preoperative period to plan appropriate treatment.

Categories: Radiology, Oncology, Orthopedics

Keywords: aneurysmal bone cyst, benign bone tumor, patella, giant cell tumor, osteoclastoma, bone

cyst

Introduction

Giant cell tumor (GCT) accounts for 4%-5% of all primary bone tumors, and it is usually seen at

the end of long bones around the knee after skeletal maturity. However, there are few case

reports of unusual location and in a few cases even in sesamoid bones such as patella [1].

Primary patellar tumors are rare; in a series of 7,975 primary bone tumors, Dahlin and his co-

workers reported only 10 (0.12%) patellar lesions [2]. A majority (70-90%) of the patellar tumors

Received 04/17/2019 are benign. The most common tumor is GCT (33%) followed by chondroblastoma (16%) [1,3-5].

Review began 06/03/2019

A combined GCT and aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is extremely rare in the patella, and only four

Review ended 09/24/2019

Published 10/01/2019

case reports are available in medical literature till date [6-9]. We hereby submit a case of

patellar GCT with secondary ABC in a young female who presented with pain and swelling on

© Copyright 2019

the anterior part of the knee. We have taken due consent from the patient regarding the

Tripathy et al. This is an open access

article distributed under the terms of

publication of this case.

the Creative Commons Attribution

License CC-BY 3.0., which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and Case Presentation

reproduction in any medium, provided

A 15-year-old girl was presented with complains of pain and swelling in the right knee for the

the original author and source are

last one year. She was limping for the last six months with gradual progression of symptoms.

credited.

There was no trauma history, fever, weight loss, loss of appetite or history of exposure to

How to cite this article

Tripathy S K, Doki S, Behera G, et al. (October 01, 2019) Giant Cell Tumor with Secondary Aneurysmal

Bone Cyst of the Patella: A Case Report. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819

tuberculosis. Examination revealed that the swelling was anterior and was arising from the

underlying patella bone (Figure 1). The swelling was tender to deep pressure. There was no

localized warmth, synovial thickening, effusion or skin adhesion over the swelling. The range of

motion of her knee was 0 to 60 degrees with terminal flexion being painful. There was no

ligamentous instability in the knee, and there was no distal neurovascular deficit.

FIGURE 1: Clinical picture of the patient showing swelling of

the right knee

Laboratory studies revealed hemoglobin of 11.4gm/dl and white cell count of 9,700 cells/mm 3.

Differential counts were within normal range - ESR was 20, C-reactive protein was negative,

and alkaline phosphate was within normal limits. Mantoux test was non-reactive. Radiographs

of the right knee showed lytic and expansile lesion involving the entire patella with thinned out

cortex in a diffuse pattern suggesting a benign lesion (Figure 2). There was no periosteal

reaction. Computed tomography scan clearly delineated the lesion (Figure 3). The lesion on

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was T2-hyperintense with small multiple fluid pockets.

There were areas with hemorrhagic component and cortical breach (Figure 4). Based on these

clinic-radiological findings, a diagnosis of GCT of the patella was made with a differential

diagnosis of ABC and telangiectatic osteosarcoma. A core needle biopsy revealed it to be GCT

of the patella. The patient was searched for other metastatic foci in the chest, but her chest x-

ray and CT scan were normal.

2019 Tripathy et al. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819 2 of 8

FIGURE 2: Radiograph of the right knee showing expansile

lytic lesion of the whole patella

FIGURE 3: Computed tomography scan shows complete

involvement of whole patella with no soft tissue extension

2019 Tripathy et al. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819 3 of 8

FIGURE 4: Sagittal (A, B) and axial cut sections show T2-

weighted hyperintense signal with no involvement of overlying

soft tissue

Total patellectomy with extensor repair was planned. Intraoperatively, it was found that the

whole patella was involved, and the cortical structure was so thinned out that it could be

deformed with slight pressure from a finger leading to overall destruction of the patella. There

was no invasion of surrounding soft tissue (Figure 5A). The patient underwent total

patellectomy and extensor mechanism was repaired with an end-to-end repair of quadriceps

tendon to patellar tendon (Figure 5B). Intraoperatively, the flexion of the knee was full. The

whole specimen was sent for histopathological study. Microscopically the tumor consisted of

spindle-shaped mononuclear cells with osteoclastic giant cells. The foci of hemorrhage,

hemosiderin deposits, and aggregates of histiocytes were found confirming the diagnosis of

aneurysmal bone cyst secondary to giant cell tumor (Figure 6).

2019 Tripathy et al. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819 4 of 8

FIGURE 5: A-Excised specimen of patella shows blood filled

cavity with in the patella and occasional break in cortex, B-

Extension mechanism repair by tying Quadriceps tendon to

patellar tendon with Ethibond No 5 suture

FIGURE 6: Microscopic picture (normal and magnified view) of

excised specimen of patella shows spindle-shaped

mononuclear cells with osteoclastic giant cells. Foci of

hemorrhage, hemosiderin deposits and aggregates of

histiocytes were found confirming the diagnosis of aneurysmal

bone cyst secondary to giant cell tumor

In the postoperative period, the limb was splinted with a posterior slab for 4 weeks to prevent

knee flexion, and then gradual knee flexion was started. At the end of six months, the patient

had a complete range of motion (0 to 130 degree) with a normal gait, and there were no

complaints. On subsequent follow up at 24-months, there were no clinical or radiological signs

of local recurrence (Figure 7) or distant metastasis.

2019 Tripathy et al. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819 5 of 8

FIGURE 7: Follow up radiograph at 2-years shows absence of

patella with no signs of recurrence

Discussion

The overall incidence of ABC is 1.4% and typically seen in long bones and spine of children and

young adults [10-13]. About 70% of ABCs are primary and arise de novo. Secondary ABCs (30%)

are normally associated with GCT, chondroblastoma, osteoblastoma, non-ossifying fibroma,

fibrous dysplasia, chondromyxoid fibroma, eosinophilic granuloma, or osteosarcoma [10-13].

The association of secondary ABC has been seen in 14% of GCT [1,10-13]. Although GCT and

ABC are common benign tumors of the patella, a combined GCT and ABC case is extremely rare

[6-9].

The clinical presentation of GCT with secondary ABC is the same as that of isolated GCT in

patella [6-9]. Pain, swelling, and restriction of movement may be there in any lesion of the

patella; hence, radiological and histological evaluations are crucial. It has been reported that

only 20% of secondary ABCs have a typical radiologic appearance and in 80% of the cases, the

main tumor dominates the radiological picture [14]. Unless the fliud level is visualized on MRI,

it is difficult to suspect ABC. Overall the diagnosis relies on histopathology only. Again, on

biopsy, if the material is aspirated from the cystic space, it may reveal hemorrhage and mislead

the diagnosis or point towards ABC only [7,9]. Hence, multiple specimens from cystic as well as

solid areas of tumors are essential to confirm the diagnosis from histopathology. Low et al. and

Yo et al. have warned that a small biopsy and limited sample may be mischievous in combined

2019 Tripathy et al. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819 6 of 8

ABC and GCT [7,9].

Although the combined GCT and ABC may sound interesting, ABC has no implications as far as

the management or the outcome of treatment of GCT is concerned [6-9]. However, it is

surprising to see some of the previous reports in which the authors have directly proceeded for

surgery without doing a tissue diagnosis in the preoperative period [7-8]. Song et al. and Yu et

al. cited many differential diagnoses (GCT, ABC, telangiectactic osteosarcoma, and giant cell

reparative granuloma) based on clinical and radiological findings, but they all directly went for

surgery without preoperative or intraoperative tissue diagnosis [7-8]. The role of tissue

diagnosis using a core needle biopsy can neither be overlooked nor underestimated [15]. This

process is minimally invasive and provides a clue to the operating surgeon preoperatively. The

most important benefit is that it can exclude malignant pathology in case the treatment is

different. Low et al. and Marudanayagam et al. performed the intraoperative frozen section and

preoperative core needle biopsy respectively to establish the diagnosis [6,9]. However, both

these authors stressed on the avoidance of limited sample or small biopsy as in both of their

cases they could diagnose only ABC and missed the GCT. Great caution must be taken while

performing core needle biopsy preoperatively as there is a high chance of taking the material

only from the cystic space which may erroneously give the result of ABC. The fear is that

missing a concomitant malignant pathology in ABC may have grave consequence. Solid and

cystic material must be obtained at various sites of the lesion to a have proper preoperative

diagnosis. There must be a preoperative precise tissue diagnosis in patellar lesion to plan

appropriate treatment.

In the previously reported cases, the area of involvement was not much extensive. The authors

had curated the lesion and filled up the defect with a bone graft or bone graft substitute or

cement [6-9]. They all have reported excellent outcome with no evidence of recurrence. In our

case, the lesion was aggressive with a cortical breach, and there was overall destruction of the

patella, so we preferred total patellectomy and reconstruction of the extensor mechanism.

Complete patellectomy has been recommended in some of the reports of isolated GCT

patella. The outcome of complete patellectomy needs to be assessed from the reports as it is the

extreme form of the disease for which such treatment was planned. Again, it involves complete

removal of the patella and the extensor mechanism repair; hence, the functional outcome may

be different or compromised as compared to another relatively simple approach such as

curettage and filling up the defect. Only one case of total patellectomy has been reported in

GCT of the patella. Malhotra et al. reported a case of aggressive GCT treated with total

patellectomy and extensor mechanism repair using a patellar allograft [16].

GCT lesions are locally aggressive with high chances of recurrence rate. It has been reported

that the incidence of metastasis is up to 1%-2% [17-19]. To exclude metastasis, we evaluated

the case with chest x-ray and CT scan. Many authors report that GCT recurrence is high during

the initial two years [17-19]. At 24-months of surgery, the patient was free of symptoms; there

was no radiological evidence of recurrence or distant metastasis. Even then a long-term follow-

up is essential and the patient is still under our follow-up.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the diagnosis of GCT with secondary ABC is solely based on histopathological

analysis. The clinical and radiological findings are nonspecific. It is imperative to obtain a

precise tissue diagnosis in the preoperative period to plan appropriate treatment. A

preoperative diagnosis of GCT may not change the treatment of combined GCT and ABC in the

patella, but a concomitant malignant pathology in ABC if missed may have grave consequence.

Additional Information

2019 Tripathy et al. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819 7 of 8

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Conflicts of interest:

In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from

any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared

that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any

organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All

authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to

have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Singh J, James SL, Kroon HM, Woertler K, Anderson SE, Davies AM: Tumour and tumour-like

lesions of the patella - a multicentre experience. Eur Radiol. 2009, 19:701-712.

10.1007/s00330-008-1180-x

2. Unni KK: Dahlin’s Bone Tumours: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases . Unni KK (ed):

Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 5th Revised edition, Philadelphia; 1996.

3. Ferguson PC, Griffin AM, Bell RS: Primary patellar tumors . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997,

336:199-204.

4. Kransdorf MJ, Moser RP Jr, Vinh TN, Aoki J, Callaghan JJ: Primary tumors of the patella. a

review of 42 cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1989, 18:365-371. 10.1007/BF00361426

5. Mercuri M, Casadei R: Patellar tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001, 389:35-46.

6. Marudanayagam A, Gnanadoss JJ: Secondary anerysmal bone cyst of the patella: a case report .

Iowa Orthop J. 2006, 26:144-146.

7. Yu X, Guo R, Fan C, et al.: Aneurysmal bone cyst secondary to a giant cell tumor of the

patella: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2016, 11:1481-1485. 10.3892/ol.2016.4080

8. Song M, Dai W, Sun R, et al.: Giant cell tumor of the patella with a secondary aneurismal bone

cyst: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2016, 11:4045-4048. 10.3892/ol.2016.4540

9. Low SF, Hanafiah M, Nurismah MI, Suraya A: Challenges in imaging and histopathological

assessment of a giant cell tumour with secondary aneurysmal cyst in the patella. BMJ Case

Rep. 2013, 2013:pii: bcr2013200790. 10.1136/bcr-2013-200790

10. Freiberg AA, Loder RT, Heidelberg KP, Hensinger RN: Aneurysmal bone cyst in young

children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994, 14:86-91. 10.1097/01241398-199401000-00018

11. Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L: Solitary unicameral bone cyst with emphasis on the roentgen

picture, the pathologic appearance and the pathogenesis. Arch Surg. 1942, 44:1004-1025.

10.1001/archsurg.1942.01210240043003

12. Oh JH, Kim HH, Gong HS, Lee SL, Kim JY, Kim WS: Primary aneurysmal bone cyst of the

patella: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2007, 15:234-237.

10.1177/230949900701500223

13. Wu Z, Yang X, Xiao J, et al.: Aneurysmal bone cyst secondary to giant cell tumor of the mobile

spine: a report of 11 cases. Spine . 2011, 36:E1385-E1390. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820e60b2

14. Bonakdarpour A, Levy WM, Aegerter E: Primary and secondary aneurysmal bone cyst: a

radiological study of 75 cases. Radiology. 1978, 126:75-83. 10.1148/126.1.75

15. Song M, Zhang Z, Wu Y, Ma K, Lu M: Primary tumors of the patella . World J Surg Oncol. 2015,

25:163. 10.1186/s12957-015-0573-y

16. Malhotra R, Sharma L, Kumar V, Nataraj AR: Giant cell tumor of the patella and its

management using a patella, patellar tendon, and tibial tubercle allograft. Knee Surg Sports

Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010, 18:167-169. 10.1007/s00167-009-0908-8

17. Athanasou NA, Bansal M, Forsyth R, Reid RP, Sapi Z: Giant cell tumor of bone. World Health

Organization Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA,

Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F (ed): IARC Press, Lyon; 2013. 4:321-324.

18. Yoshida Y, Kojima T, Taniguchi M, Osaka S, Tokuhashi Y: Giant-cell tumor of the patella . Acta

Med Okayama. 2012, 66:73-76.

19. Shibata T, Nishio J, Matsunaga T, Aoki M, Iwasaki H, Naito M: Giant cell tumor of the patella:

an uncommon cause of anterior knee pain: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015, 3:207-211.

10.3892/mco.2014.433

2019 Tripathy et al. Cureus 11(10): e5819. DOI 10.7759/cureus.5819 8 of 8

You might also like

- EKG/ECG Study GuideDocument13 pagesEKG/ECG Study GuideSherree HayesNo ratings yet

- Grammar Tests Upper Intermediate Determiners ...Document4 pagesGrammar Tests Upper Intermediate Determiners ...silvia0% (1)

- Hand and Wrist AAOS MCQ. 2019 PDFDocument158 pagesHand and Wrist AAOS MCQ. 2019 PDFantonio ferrer100% (2)

- TFN Reviewer PrelimsDocument8 pagesTFN Reviewer PrelimsCUBILLAS, JASMIN G.No ratings yet

- GCT ThumbDocument10 pagesGCT ThumbMoeez AkramNo ratings yet

- Giant Cell Tumor of The Phalanx of Finger: Case Reports: BackgroundDocument10 pagesGiant Cell Tumor of The Phalanx of Finger: Case Reports: BackgroundMoeez AkramNo ratings yet

- Sleeve Fracture of The Adult PatellaDocument3 pagesSleeve Fracture of The Adult PatellaRadenMasKaerNo ratings yet

- Giant Cell Tumor of Distal End of Femur With Pathological Fracture Treated by Resection and Megaprosthesis A Case ReportDocument5 pagesGiant Cell Tumor of Distal End of Femur With Pathological Fracture Treated by Resection and Megaprosthesis A Case ReportInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Management of Non-Metastatic Pelvic Bone Giant Cell Tumour by Resection, Extended Curettage and Reconstruction With Autograft and Allograft - A Case ReportDocument5 pagesManagement of Non-Metastatic Pelvic Bone Giant Cell Tumour by Resection, Extended Curettage and Reconstruction With Autograft and Allograft - A Case ReportInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Giant Cell Tumor of The Tendon Sheath: A Rare Case in The Left Knee of A 15-Year-Old BoyDocument3 pagesGiant Cell Tumor of The Tendon Sheath: A Rare Case in The Left Knee of A 15-Year-Old BoyFriadi NataNo ratings yet

- Osteoblastoma A Spectrum of Presentation and TreatDocument10 pagesOsteoblastoma A Spectrum of Presentation and TreatmandetoperdiyuwanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2049080122008718 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2049080122008718 MainFarizka Dwinda HidayatNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Osteomyelitis of The Patella in A 10-Year-Old Girl: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocument6 pagesCase Report: Osteomyelitis of The Patella in A 10-Year-Old Girl: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureIfal JakNo ratings yet

- Giant Cell Tumor of Tendon Sheath YjfasDocument6 pagesGiant Cell Tumor of Tendon Sheath YjfasPaulo Victor Dias AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- He 2019Document10 pagesHe 2019Rashif AkmalNo ratings yet

- Osteosarcoma of The Jaw: Report of 3 Cases (Including The Rare Epithelioid Variant) With Review of LiteratureDocument10 pagesOsteosarcoma of The Jaw: Report of 3 Cases (Including The Rare Epithelioid Variant) With Review of LiteraturesTEVENNo ratings yet

- Multifocal Giant Cell Tumor of The Carpus Unusua 2024 International JournalDocument5 pagesMultifocal Giant Cell Tumor of The Carpus Unusua 2024 International JournalRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Isolated Lesser Trochanter Fracture Associated With LeukemiaDocument3 pagesIsolated Lesser Trochanter Fracture Associated With LeukemiaIndora DenniNo ratings yet

- Giant Cell Tumor of The Thoracal Spine Case Report 2020Document4 pagesGiant Cell Tumor of The Thoracal Spine Case Report 2020Ignatius Rheza SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Ispub 14140Document7 pagesIspub 14140Okkie Mharga SentanaNo ratings yet

- Ringe 2013Document3 pagesRinge 2013Minh ChíNo ratings yet

- 2020 Infantile Tuberculous Osteomyelitis of The Proximal TibiaDocument4 pages2020 Infantile Tuberculous Osteomyelitis of The Proximal TibiaMuhammad Muttaqee MisranNo ratings yet

- A Case of Eccrine Tumour Metastasis To Spine Managed With Posterior Spinal Stabilization With Recovering ParaparesisDocument3 pagesA Case of Eccrine Tumour Metastasis To Spine Managed With Posterior Spinal Stabilization With Recovering ParaparesisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Cervical Osteomyelitis and An Epidural Abscess: An Unusual Form of Cat-Scratch Disease in One CaseDocument5 pagesCervical Osteomyelitis and An Epidural Abscess: An Unusual Form of Cat-Scratch Disease in One CaseRashmeeta ThadhaniNo ratings yet

- Primary Normo-Phosphatemic Tumoral Calcinosis - A Rare EntityDocument4 pagesPrimary Normo-Phosphatemic Tumoral Calcinosis - A Rare EntityIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Extra Cranial MetastasesDocument5 pagesExtra Cranial MetastasesJayendra Kumar AryaNo ratings yet

- Metastatic Vertebral Lesion Mimicking An Atypical Hemangioma WithDocument8 pagesMetastatic Vertebral Lesion Mimicking An Atypical Hemangioma Withsica_17_steaua6519No ratings yet

- Aspe 02 0177Document3 pagesAspe 02 0177igeltangdiayuNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0012 00000008855 PDFDocument11 pagesCureus 0012 00000008855 PDFAlberto BrahmNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Advances in Case ReportsDocument3 pagesInternational Journal of Advances in Case ReportsastritriNo ratings yet

- 1808 8694 Bjorl 86 s1 0s23Document3 pages1808 8694 Bjorl 86 s1 0s23VITOR PEREZNo ratings yet

- Tuberculous Osteomyelitis Mimicking A Lytic Bone Tumor: Report of Two Cases and Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesTuberculous Osteomyelitis Mimicking A Lytic Bone Tumor: Report of Two Cases and Literature ReviewazevedoNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Spontaneous Rupture of Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of PancreasDocument8 pagesMedicine: Spontaneous Rupture of Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of PancreasPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Potts Puffy Tumour 4Document3 pagesPotts Puffy Tumour 4kityamuwesiNo ratings yet

- Adi Wasis Prakosa - Poster FulltextDocument11 pagesAdi Wasis Prakosa - Poster FulltextAdi Wasis PrakosaNo ratings yet

- Primum Non Nocere - First Do No HarmDocument4 pagesPrimum Non Nocere - First Do No HarmSuci AprilyaNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Large Size Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma of AnkleDocument5 pagesA Rare Case of Large Size Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma of AnkleIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Keithbidwell 1987Document5 pagesKeithbidwell 1987Ignatius Rheza SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Ecr2015 c-1165Document28 pagesEcr2015 c-1165Fitri Amelia RizkiNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 713Document5 pages2017 Article 713فرجني موغNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Zehava Sadka Rosenberg, 1 Steven Shankman, 1 Michael Klein, 2'3 and Wallace Lehman4Document3 pagesCase Report: Zehava Sadka Rosenberg, 1 Steven Shankman, 1 Michael Klein, 2'3 and Wallace Lehman4Mohamed Ali Al-BuflasaNo ratings yet

- Unusual Presentation of Adamantinoma With Synchronous 2024 International JouDocument5 pagesUnusual Presentation of Adamantinoma With Synchronous 2024 International JouRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- ONCO 21 Desember 2020 Undiferentiated Pleomorfic Sarcoma Rev 1Document46 pagesONCO 21 Desember 2020 Undiferentiated Pleomorfic Sarcoma Rev 1ciptakarwanaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document6 pagesJurnal 2alexxxxxNo ratings yet

- Visual Diagnosis in Emergency Medicine: Superior Dislocation of The Patella: Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocument3 pagesVisual Diagnosis in Emergency Medicine: Superior Dislocation of The Patella: Case Report and Review of The LiteratureTrisna AuliaNo ratings yet

- Patellar Tendon Avulsion With Tibial Tuberosity SLDocument4 pagesPatellar Tendon Avulsion With Tibial Tuberosity SLKirana ArinNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 05837Document9 pagesIjerph 19 05837chan kyoNo ratings yet

- Plantillo Anteromedial + LCP + ApeDocument7 pagesPlantillo Anteromedial + LCP + ApeThiagoNo ratings yet

- Mandibular Traumatic Peripheral Osteoma: A Case ReportDocument5 pagesMandibular Traumatic Peripheral Osteoma: A Case ReportrajtanniruNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis of Talus A Case ReportDocument4 pagesTuberculosis of Talus A Case ReportPutra DariusNo ratings yet

- Giant CellDocument5 pagesGiant CellTamimahNo ratings yet

- Primary Ewing Sarcoma of The Adrenal Gland: A Rare Cause of Abdominal MassDocument6 pagesPrimary Ewing Sarcoma of The Adrenal Gland: A Rare Cause of Abdominal MassAndra KurniantoNo ratings yet

- TB Arthritis Ankle Mimicking SynovitisDocument8 pagesTB Arthritis Ankle Mimicking SynovitisAzmi FarhadiNo ratings yet

- 485-Article Text-5030-1-10-20100605 PDFDocument4 pages485-Article Text-5030-1-10-20100605 PDFAndreas NatanNo ratings yet

- Cuti Bacterium 2019 Aid2019Document10 pagesCuti Bacterium 2019 Aid2019Vita BūdvytėNo ratings yet

- Caso Clinico Sp3Document4 pagesCaso Clinico Sp3eduardoNo ratings yet

- Clavicle Fracture Following Neck Dissection: Imaging Features and Natural CourseDocument6 pagesClavicle Fracture Following Neck Dissection: Imaging Features and Natural CourseAngel IschiaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1991790212001626Document6 pagesPi Is 1991790212001626Lina NiatiNo ratings yet

- Scientific Abstracts Friday, 14 June 2019 1015Document1 pageScientific Abstracts Friday, 14 June 2019 1015حسام الدين إسماعيلNo ratings yet

- Mi TsuyamaDocument8 pagesMi TsuyamatnsourceNo ratings yet

- Osteomielitis PatelarDocument3 pagesOsteomielitis PatelarAlexander DanielNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument5 pages1 PBrahmat senjayaNo ratings yet

- Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: Indications, Surgical Techniques and ComplicationsFrom EverandUnicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: Indications, Surgical Techniques and ComplicationsTad L. GerlingerNo ratings yet

- Infantile Hemangioendothelioma: Bafana Elliot Hlatshwayo, Daba Ipfi, Sipho SitholeDocument4 pagesInfantile Hemangioendothelioma: Bafana Elliot Hlatshwayo, Daba Ipfi, Sipho SitholeDrAbdullah HajarNo ratings yet

- Spectrum of Teratoma: From Head To Toe, Radiological Pathological CorrelationDocument33 pagesSpectrum of Teratoma: From Head To Toe, Radiological Pathological CorrelationDrAbdullah HajarNo ratings yet

- AIUM Practice Parameter For The Performance of A Peripheral Venous Ultrasound ExaminationDocument8 pagesAIUM Practice Parameter For The Performance of A Peripheral Venous Ultrasound ExaminationDrAbdullah HajarNo ratings yet

- NEW Sat 1255 Imperial Whitelaw Protocols NEWDocument5 pagesNEW Sat 1255 Imperial Whitelaw Protocols NEWDrAbdullah HajarNo ratings yet

- We Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsDocument12 pagesWe Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsDrAbdullah HajarNo ratings yet

- CMR 00062-17Document78 pagesCMR 00062-17pokhara144No ratings yet

- English 10 1st Quarter Examination 22Document4 pagesEnglish 10 1st Quarter Examination 22Christian Jay PresiidenteNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument10 pagesArticleperley.matiasNo ratings yet

- LIFESCI 2N03: Human: Nutrition For Life ScienceDocument40 pagesLIFESCI 2N03: Human: Nutrition For Life ScienceAnnalisa NguyenNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of Focused Assessment With Sonography For Trauma (FAST) in Blunt Trauma Abdomen - A Prospective StudyDocument5 pagesAccuracy of Focused Assessment With Sonography For Trauma (FAST) in Blunt Trauma Abdomen - A Prospective StudyEdison HernandezNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Mental Health Screening Into Adolescent Office VisitsDocument3 pagesIncorporating Mental Health Screening Into Adolescent Office VisitsnataliasulistyoNo ratings yet

- Harga KhususDocument16 pagesHarga KhususNoperitaNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Speech On HealthcareDocument4 pagesPersuasive Speech On HealthcareRobanderson126No ratings yet

- Revised PPAR-Q Aug. 2022Document2 pagesRevised PPAR-Q Aug. 2022RAY LORENZO LAGASCANo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ckd-EpiDocument6 pagesJurnal Ckd-EpinezaNo ratings yet

- D HC OperatorsDocument5,396 pagesD HC OperatorsCoupon VampireNo ratings yet

- P.e12 Lesson Safety ProtocolDocument23 pagesP.e12 Lesson Safety ProtocolArcLosephNo ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Akper BookDocument4 pagesCardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Akper BookFitriana Noor SabrinaNo ratings yet

- Summer and Winter VacationsDocument5 pagesSummer and Winter VacationsYahia IdressNo ratings yet

- E-Cigarette Wholesale Distributor in USA - Vape Supplier in USADocument10 pagesE-Cigarette Wholesale Distributor in USA - Vape Supplier in USAAnjum JohnNo ratings yet

- HIS Analogy ExplanationDocument1 pageHIS Analogy ExplanationJake PendonNo ratings yet

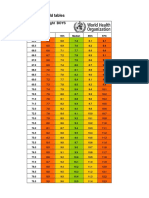

- Boys Simplified Field Tables Weight For Length 2 To 5 Years (Percentiles)Document4 pagesBoys Simplified Field Tables Weight For Length 2 To 5 Years (Percentiles)Gabrielly LopesNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Central Mindanao University College of NURSING University Town, Musuan, Maramag, BukidnonDocument2 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Central Mindanao University College of NURSING University Town, Musuan, Maramag, BukidnonJastine SabornidoNo ratings yet

- 02 - Establishing Background Levels - EPA - 1995Document7 pages02 - Establishing Background Levels - EPA - 1995JessikaNo ratings yet

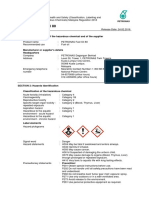

- Instructions For Use: Technical InformationDocument5 pagesInstructions For Use: Technical InformationRiska SagitaNo ratings yet

- Ad Iver Nion Ad Iver Nion Ad Iver NionDocument8 pagesAd Iver Nion Ad Iver Nion Ad Iver NionMad River UnionNo ratings yet

- Eustachian TubeDocument6 pagesEustachian TubeNaruto_Uchiha777No ratings yet

- Walkthrough21 PDFDocument51 pagesWalkthrough21 PDFAnas SantyNo ratings yet

- Rinchuse 2006Document10 pagesRinchuse 2006Natalie JaraNo ratings yet

- PETRONAS Fuel Oil 80: Safety Data SheetDocument10 pagesPETRONAS Fuel Oil 80: Safety Data SheetJaharudin JuhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document55 pagesChapter 10Aimah ManafNo ratings yet

- Operating RoomDocument13 pagesOperating RoomrichardNo ratings yet