Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Difficulties Encountered in The Translation of Legal Texts - Turkey

Uploaded by

Jorge Nuno0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views27 pagesOriginal Title

Difficulties encountered in the translation of Legal Texts - Turkey

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views27 pagesDifficulties Encountered in The Translation of Legal Texts - Turkey

Uploaded by

Jorge NunoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 27

4

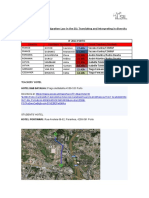

October 2002

Dr Ayfer Altay, Head

of the English

Division of the

Department of

Translation and

Interpretation of

Hacettepe

University, Ankara, Difficulties Encountered in the

Turkey is a graduate

of the Department of Translation of Legal Texts:

English Language

and Literature of

Ankara University,

The Case of Turkey

and got her MA

Degree in English by Dr. Ayfer Altay

Literature and her

Ph.D. in English

Literature and

Linguistics from the

same University.

Since 1987, she has Introduction

been working at the

Department of

Translation and

he problems encountered in translating legal texts,

Interpretation, which are categorised below, are specific to legal

having been translation between the English and Turkish languages

involved in

"translation" both

and legal systems. These problems are mostly

professionally and encountered by students learning legal translation, in

academically. In our case those at the department of Translation and

1990, after being

selected by a series

Interpretation at Hacettepe University in Turkey.

of exams, the

Turkish Government

While lawyers The problems will be studied under

sent her to Brussels,

for a 6-month cannot expect six main categories, which are likely

traineeship program translators to to be quite broad. Such a study

at EEC. There, she

produce parallel could have been applied to the

studied EEC Law, its

structure, translation texts that are limited examples from a limited

of legal texts, and identical in source or from a certain area of law.

also participated in

meaning, they do Alternatively one of the categories

the translation of the

Treaties Establishing expect them to could have been taken as the point

the Community into produce parallel of concentration and the idea could

Turkish. Presently

texts that are have been developed further.

she primarily

teaches "translation identical in their However, I have tried to put

of legal texts" at the legal effect. forward the major sources of errors

Department. She and problems due to the differences

also translates legal

texts for

in legal systems and languages.

Government

organisations. These categories have arisen from my twelve years of

Currently she is busy

with preparing a

personal experience as an instructor of translation of

book on "Translation legal texts. The article will discuss mainly syntactic

of Legal Texts."

arrangements. Arguments on semantic and pragmatic

Dr. Altay can be

reached at models concerning phraseology and textology in

ayferaltay@yahoo.co doctrines in international law or comments on parallel

m textuality in legal matters and on legal authenticity will

.

not be provided for the time being, since they would

broaden the subject excessively.

Before studying the problems and difficulties of

translating legal texts, first we shall describe the

historical and linguistic backgrounds which made both

Turkish and English legal languages become what they

are today, because the difficulties arise mainly due to

the differences in linguistic systems and languages.

Therefore, we shall start with The Bases of the English

Legal Language (although these may be well-known to

the British reader). Then, The Bases of the Turkish Legal

System and The Nature of the Turkish Legal Language

Front Page will be discussed briefly. Before studying the problems

and difficulties of legal translation, the general features

July ‘02 of legal language, and the common features of the

Issue English and Turkish legal languages will be discussed

very briefly.

April ‘02

Issue

Bases of the English Legal Language

January ‘02

Issue It is impossible to fully appreciate the nature of legal

language without having some familiarity with its

October ‘01 history. There is no single answer to the question of

Issue how legal language came to be what it is (Tiersma

1999:47). Since much of the explanation can be found

July ‘01 in the historical events which have left their mark on the

Issue language of English law, we should first take a glance at

the historical background of today's British legal

April ‘01 language.

Issue

Like their language, the law of the British Celts had little

January ‘01 lasting impact on the English legal system. The

Issue Germanic invaders who spoke Anglo-Saxon or Old

English developed a type of legal language, the

October ‘00 remnants of which have survived until today, such as

Issue "bequeath," "theft," "guilt," "land." The Anglo-Saxons

made extensive use of alliteration in their legal

July ‘00 language, which survived in today's English legal

language in expressions such as "aid and abet," "any

Issue

and all," etc.

April ‘00

Issue Even without alliteration, parallelism was an important

stylistic feature of Anglo-Saxon legal documents, which

January ‘00 has also survived. Even today witnesses swear to tell

Issue "the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth"

(Tiersma 1999:15).

October ‘99

Issue A significant event for the language and law of England

was the spread of Christianity in 597, since it promoted

July ‘99 writing in Latin. Through the Roman Catholic Church the

Issue Latin language once again had a major presence in

England. Its influence extended to legal matters,

April ‘99 particularly by means of the Canon Law, through which

Issue the Church regulated religious matters such as marriage

and family. The use of Latin as legal language

January ‘99 introduced terms like "client," "admit," and "mediate"

Issue (Tiersma 1999:16).

October ‘98 After the Duke of Normandy claimed the English throne

Issue and invaded England in 1066, the main impact of this

Norman conquest on the written legal language was to

July ‘98 replace English with Latin (Tiersma 1999:20). Beginning

Issue in 1310, the language of statutes was French, but it was

not until two hundred years after the Conquest that

April ‘98 French became the language of oral pleadings in the

Issue royal courts. For the next one or two centuries French

maintained its status as England's premier legal

January ‘98 language. However, in 1417, while fighting the French,

Issue King Henry V broke all linguistic ties with his Norman

ancestry and decided to have many of his official

October ‘97 documents written in English (Tiersma 1999:23).

Issue

Despite the emergence of French, Latin remained an

July ‘97 important legal language in England, especially in its

Issue written form. The fact that writs were drafted in Latin

for so long explains why even today, many of them

have Latin names. The use of Latin and tireless

repetitions by the judges have endowed these legal

maxims with a sense of timelessness and dignity;

moreover, they reflect an oral folk tradition in which

legal rules are expressed as sayings due to the ease of

remembering a certain rhythm or rhyme (Tiersma

Five Continents 1999:26).

Index 1997-

2002 These poetic features are still occasionally found in the

English legal language. Latin has also remained in

expressions relating to the names of cases and parties;

Translator

Profiles

for example, in England the term for the crown in

Translator, criminal case names is "Rex or Regina" (Tiersma

Teacher, 1999:27).

Businesswoman,

Mentor

Courtney Searles- When Anglo-French died out as a living language, the

Ridge interviewed French used by lawyers and judges became a language

by Ann Macfarlane exclusive to the legal profession (Tiersma 1999:28). It

was incomprehensible both to their clients and to the

The Profession speakers of ordinary French. Legal French also

The Bottom Line contained many terms for which there were no English

by Fire Ant & equivalents.

Worker Bee

Translation and

Project

Several French terms are still common in legal English

Management such as "accounts payable/receivable," "attorney

by Celia Rico general," "court martial." The most lasting impact of

Pérez, Ph.D.

French is the tremendous amount of technical

What the Guys

Said, the Way vocabulary that derives from it, including many basic

They Said It, As words in the English legal system, such as "agreement,"

Best We Can "arrest," "estate," "fee simple," "bailiff," "council,"

by Danilo

Nogueira "plaintiff," and "plea." As in the early Anglo-Saxon

influence, which had phrases featuring the juxtaposition

of two words with closely related meaning which are

Translators and

Computers

often alliterative such as "to have and to hold," this

The Emerging Role doubling continued in legal French, often involving a

of Translation native English word together with the equivalent French

Experts in the word, since many people at the time would have been

Coming MT Era

by Zhuang Xinglai partially bilingual and would understand at least one of

the terms, for example, "acknowledge and confess,"

Legal "had and received," "will and testament," "fit and

Translation

Difficulties

proper."

Encountered in the

Translation of As we see through the Middle ages, the legal profession

Legal Texts: The

made use of three different languages. During the rest

Case of Turkey

by Dr. Ayfer Altay of 17th century, Latin and legal French continued their

slow decline.

Literary

Translation

In 1731, Parliament permanently ended the use of Latin

Cultural and French in legal proceedings; however, it became

Implications for difficult to translate many French and Latin terms into

Translation

English. With another statute, it was provided that the

by Kate James

African Writers as traditional names of writs and technical words would

Practising continue to be in the original language (Tiersma

Translators—The

Case of Ahmadou

Kourouma 1999:36), and the ritualistic language remained

by Haruna Jiyah important. The exact words of legal authorities mattered

Jacob, Ph.D.

very much to the profession. Rewriting an authoritative

Arts & text in your own words was considered to be dangerous

Entertainment and even subversive (Tiersma 1999:39). Tiersma

Performability mentioned that once established, legal phrases in

versus

Readability: A

authoritative texts take on a life of their own; you

Historical meddle with them at your own risk (1999:39). He adds

Overview of a that, in authoritative written texts, the words will

Theoretical

Polarization in

remain the same even if the spoken language and

Theatre indeed the surrounding circumstances have changed,

Translation and lawyers will use the same language even if the

by Dr. Ekaterini

Nikolarea

public no longer understands it. Once this happens, the

Translation in a professional class that is trained in the archaic language

Confined Space— of the texts becomes indispensable (Tiersma 1999:40).

Film Sub-titling

by Barbara

Schwarz All these developments throughout history have led to

an obtuse, archaic and verbose legal language in English

which is one of the main reasons of the difficulties

Caught in the

Web

encountered by Turkish translators in translating legal

Web Surfing for texts written in English.

Fun and Profit

by Cathy Flick,

Ph.D.

Translators’ On-

Line Resources Bases of the Turkish Legal System

by Gabe Bokor

The Koran (the holy book of Moslems), certain rules and

Translators’ provisions set by sources other than Koran, for example

Tools Mohammed the Prophet's words which are called the

Translators’ "traditions" or "fatwas," diversified and often

Emporium

contradictory provisions and interpretations are called in

Trados—Is It a

Must? toto "Islamic Law," under which the Ottoman Empire

by Andrei was ruled throughout the centuries.

Gerasimov

Translators’ Job

Mohammed's words are general principles of justice and

Market equity, with a high degree of objectivity and essentially

primary regulations necessitated by the social nature

and structure of the Arab community of that time. It

Letters to the

Editor must be mentioned that not only the Koran, but also the

other sources of Muslim jurisprudence were essentially

created to meet the needs of the community existing

Translators’

Events

during and after Mohammed's era (Timur 1956:85). It

must also be mentioned that throughout the centuries

the presence of different and irreconcilable religious

Call for Papers

sects among the Moslems in the area, and the continual

and Editorial

Policies

increase of the proportion of non-Moslem citizens after

the annexation of Istanbul by Sultan Mehmed the

Conqueror have created insurmountable difficulties in

jurisprudence. Moreover, Islamic Law was not broad and

comprehensive enough to offer reasonable solutions to

legal problems of every kind.

In fact, the traditions are not applicable to our

contemporary society, because Islamic Law contains no

provisions regulating the sundry relationships of political

institutions and commercial transactions of today's

world. Likewise, its rules relating to the vast field of

criminal law and jurisdiction are too limited to serve

their purpose adequately in the modern world (Timur

1956:86). Furthermore, a great many Islamic codes and

legal provisions have become impracticable because in

time they have fallen short of meeting the requirements

brought about by the continuous metamorphoses of the

communities and have completely lost their vitality. For

example thousands of articles in the Megelle (Islamic

Law), are no longer vital and integral parts of Moslem

Law due to their inapplicability. To give an example:

Polygamy, which was an accepted social phenomenon of

Arab society, has not been practiced in Turkey after

Atatürk's reforms. Due to all these shortcomings of

Islamic jurisprudence, the reforms of 1839 were a

conscious attempt to put an end to the confusion in the

judicial sphere and to extend legal equality to all citizens

without any discrimination based on religious affiliation.

In 1841 a criminal code was drawn up. Although laws

regulating land and sea trade appeared, there was still

no legislation with regard to family and marital

relationships, which constitute an integral part of society

(Timur 1956: 75).

Following the 1923 Lausanne Peace Conference, the

Turkish government of the new republican regime in

Turkey decided that the legal codes should be modeled

after the legal systems of modern European states. The

extensive legislative work conducted under the

leadership of Atatürk was not a haphazard selection

based on an irrational admiration of the European legal

systems, but an inevitable solution to the paradoxes and

conflicts described above (Timur 1956: 76).

The legal system of the old Turkish state of the

Ottomans was based on religious (Islamic) principles,

i.e., throughout the centuries the rules of religion were

regarded as legal rules. The political development in the

19th century brought about closer contact between

Turkey and the Western world, and this necessitated a

reform in the judicial system. After the new Turkish

Republic was founded in 1923, the Islamic legal system

of the Ottoman Empire was discarded in 1924 and was

substituted by secular law. Thus, reform of private law

became inevitable. As the time available for the

preparation of a new national civil code was limited,

there remained for the Turkish jurists only one

possibility: the Swiss Civil Code which with its

popularity, clarity, and especially with its simple style

was suitable for the purpose (Izveren 1956:93) .

Turkey has used the Swiss, German, and Italian codes

as models in the field of private and public law.

However, no foreign penal codes were adopted. By

adoption of a foreign code (Timur 1956:77), we do not

mean that a foreign system was adopted in toto. Only

the legal framework of other nations, but not all the

foreign laws or the entire foreign system were adopted.

The new legal system was created with close attention

paid to local conditions. The legal system of a nation is

closely tied to the national character. The legal system

of one country cannot be adopted by another without

adopting the national character of the former as well.

Turkey adopted the Swiss Civil Code and the Swiss Code

of Obligations. The application of these codes by the

Turkish courts resulted in a Turkish Civil Code and a

Turkish Law of Obligations. The new Turkish Civil Law

was inspired by Swiss ideas whenever these were not in

conflict with the moral and social principles of the

Turkish people (Ayiter 1956:42).

Nature of the Turkish Legal Language

Language reform, which is one of the most widely an

ardently discussed cultural problems in modern Turkey,

is an issue directly related to the legal language used in

Turkey today.

Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the modern Turkish

Republic, aimed at creating a nationalist, secular,

populist, revolutionary, and etatist republic. However,

the Turkish language at that time was Ottoman Turkish,

full of numerous Arabic and Persian words which was

regarded as a disgrace because nationalism, the main

ideology of "Kemalism" demanded the purification of the

Ottoman Language by replacing its foreign elements

with genuine Turkish words. Atatürk's cultural

orientation which was based on a complete break with

the Islamic past and the adoption of the secular values

of modern western civilisation also supported this

tendency. Therefore, the Latin script was introduced.

Atatürk did not intend to create a new language as a

result of a slow, evolutionary process, but by drastic

measures within a short time. Thus he created a

national association, the Turkish Linguistic Society,

which was entrusted with the systematic reform of the

Turkish language in close co-operation with the Ministry

of Education, the Republican People's Party and the

People's Houses (Halkevleri). In 1928, which is

considered the beginning of Atatürk's "language

revolution" in Turkey, the Turkish National Assembly

amended Article 2 of the Constitution as "the religion of

the State of Turkey is Islam, its official language is

Turkish," and a few months later, the new Turkish

alphabet composed of Latin characters was adopted by

Parliament. In 1932, the Turkish Linguistic Society

whose aim was "to bring out the genuine beauty and

richness of the Turkish language and to elevate it to the

high rank it deserves among the world's major

languages" was officially founded. It was a hard task

and there were many people and institutions who were

fervently for this drastic change as well as those who

were against it. Atatürk's death in November 1938

weakened the momentum of the language revolution.

The Republican People's Party adopted its new

programme and statutes in 1939, into which many

Arabic terms previously eliminated were reinstated

(Heyd 1954:40).

However, the movement gained new impetus through

the efforts of efforts of İsmet İnönü, Atatürk's

successor. Now as the President of the Turkish Republic,

he issued a statement promising to continue the work

inaugurated by the late Atatürk for the purification of

the language from foreign elements and the evolution of

a truly national language. The most drastic expression

of the renewed purist tendencies was the translation of

the Turkish Constitution into purer Turkish. To a certain

extent, the vocabulary of the Constitution forms part of

the legal terminology, and its reform is related to that of

technical and scientific terms. The drafts prepared at the

Faculties of Law of Ankara and Istanbul Universities by a

group which included members of Parliament interested

in legal and linguistic problems and members of the

Linguistic Society were taken into consideration before a

final draft was submitted to Parliament and adopted in

January 1945. It was an exact "translation" of the

constitution of 1921 (Teşkilatı Esasiye Kanunu) which

was amended in 1924 and which was based on Arabic

vocabulary.

In the 105 articles of the new version of the

Constitution, there were only about 1410 different

words borrowed from Arabic or Persian and less than 10

European words. Many of the Arabic and Persian words

were replaced with Turkish ones, and those retained

were given a Turkish form to the extent possible (Heyd

1954:42). The new version of the Constitution was

evidently the result of a compromise between divergent

opinions.

Until that time, the puristic efforts of the Linguistic

Society had met with certain criticism by public opinion,

but during the presidency of both Atatürk and Inonu this

opposition was latent, while with the growing

democratisation of Turkish society after World War 2,

criticism became more verbal and public. Drastic

reformation of the Turkish language was strongly

opposed by Istanbul University, a large section of the

press, and also by the Istanbul Teachers' Association.

The reasons for the opposition were, among other

things, the reluctance of people to change the

vocabulary they had been used to since childhood,

reluctance of journalists and authors to use words

unknown to the public, and a widespread opinion that

language as a living organism should develop by

evolution and in accordance with its intrinsic laws. The

Linguistic Society was said to have created a new

artificial official and eurdite language very different from

the language of ordinary conversation instead of

developing the existing language so that it would be

understood even by the people on the street. Under the

influence of all this criticism, the Sixth Language

Congress, which convened in 1949, tended towards

moderation in linguistic reform. After the Extraordinary

Language Congress held in 1951, the Society's new

policy was outlined as "rejecting the views of both the

conservatives and extreme purists, and following a

middle course." The goal was to free the Turkish

language from the dominance of both eastern and

western languages. The most striking manifestation of

the opposition to the puristic policy of the Linguistic

Society with regard to our subject was the revocation of

the "translated" 1945 version of the Constitution. In

1952, by the vote of an overwhelming majority,

Parliament decided to reintroduce the old text of 1924

including later amendments but without any change in

language. At the same time, many Arabic terms were

reinstated instead of Turkish neologisms in the language

of law and administration.

Lastly, on July 9, 1961 a new version of the

Constitution, written in completely clear and modern

Turkish was submitted to a plebiscite and accepted. In

1971 and 73 some major changes were introduced into

the Constitution. Following the coup d'Ttat of 1980, the

previous Constitution was partially changed. In 1982, as

an act of restoration of the democratic order, a new

Constitution was prepared and after being submitted to

a plebiscite, it was accepted and put into force the same

year. A few amendments have been and still being

introduced to the Constitution. However, the rest of the

legislative language did not undergo a similar

purification process. While the vocabulary of the

Constitution has been updated, laws written in their

original archaic language are still being used by the

courts. Therefore, there is a large gap between the

language used by the people on the street and

legislation. From time to time, motions are tabled by the

legislature aiming at the unity and purification of the

legal language and its harmonisation with the

Constitution (Özdemir, 1969:122), but these attempts

have not resulted in concrete legislative action.

Today, after more than 50 years, it is evident that the

language reform has succeeded in changing the

vocabulary of modern Turkish to a great extent. The

vocabularies of the press, administration, scholarly

works, school textbooks, and literature are written in

Turkish using many words introduced by the Linguistic

society, along with some Arabic or Persian words.

These Arabic or Persian words can be detected

especially in the discourse of elderly people. The

presence of old and new words side by side in legal

texts, and the fact that the language of law is still

archaic Turkish including lots of Arabic and Persian

words with which the young generation is completely

unfamiliar are the main reasons for the difficulties

encountered by legal translators in Turkey.

General Features of Legal Language (Turkish and

English)

The general features of legal language that will be

discussed here apply both to English and Turkish legal

languages. As Melinkoff has suggested, "legalese" is a

way of "preserving a professional monopoly by locking

up the trade secrets in the safe of an unknown tongue"

(1963:101). On the other hand, as Tiersma suggests

quoting from Sir Edward Coke, lawyers justify keeping

the laws in an "unknown tongue" by pretending to

"protect the public" (1999:28).

Lawyers tend to defend their technical vocabulary as

essential to communication within the profession, since

they can easily understand each other using the special

terminology. Studying law is in a large measure

studying a highly technical and frequently archaic

vocabulary and a professional argot (Goodrich 1987:

176).

Law is a profession of words. The general features of

legal language that apply to both English and Turkish

legal languages are the following:

It is different from ordinary language with respect to

vocabulary and style.

The prominent feature of legal style is very long

sentences. This predilection for lengthy sentences both

in Turkish and in English is due to the need to place all

information on a particular topic in one complete unit in

order to reduce the ambiguity that may arise if the

conditions of a provision are placed in separate

sentences. Another typical feature is joining together

the words or phrases with the conjunctions "and, or" in

English and "ve, veya" (meaning "and," "or") in Turkish.

Tiersma suggests that these conjunctions are used five

times as often in legal writing as in other prose styles

(1999: 61).

Thirdly, there is abundant use of unusual sentence

structures in both languages. The law is always phrased

in an impersonal manner so as to address several

audiences at once. For example a lawyer typically starts

with "May it please the court" addressing the judge or

judges in the third person (Tiersma 1999:67) while in

Turkey court decisions begin with "Gereği dnşnnnldn"

(the necessary penalty has been decided on) when a

judge sentences somebody to a certain penalty.

Another feature is the flexible or vague language.

Lawyers both try to be as precise as possible and use

general, vague and flexible language. Flexible and

abstract language is typical of constitutions which are

ideally written to endure over time (Tiersma 1999: 80).

The features of "legalese" that create most problems are

its technical vocabulary and archaic terminology. Both

Turkish and English legal languages have retained words

that have died out in ordinary speech, the reasons of

which have been explained above. Historical factors and

stylistic tradition explain the character of present-day

English and Turkish legal languages. Many old phrases

and words can be traced back to Anglo-Saxon, old

French, and Medieval Latin, while in Turkish they can be

traced back to the Persian used in the Ottoman Empire.

Archaic vocabulary and the grammar of authoritative

older texts continue to influence contemporary legal

language in both Turkey and Britain because, just as the

Bible or the Koran is the authoritative source of religion

for believers, documents such as statutes, constitutions,

or judicial opinions are the main sources of law for the

legal profession (Tiersma 1999:96). And in Turkey, just

as the religious circles are reluctant in changing the

Arabic language of the Koran into Turkish language, the

legal circles are reluctant to change and modernise the

Arabic-influenced archaic language of the Turkish legal

language.

Legal language is conservative because reusing tried

and proven phraseology is the safest course of action

for lawyers. Archaic language is also authoritative, even

sounds majestic both in Turkish and English. As Tiersma

suggests "using antiquated terminology bestows a sense

of timelessness on the legal system as something ...

deserving of great respect" (1999:97).

In Turkey, old people using the same kind of archaic

language inspire awe in most of us.

In both legal languages there are many words that have

a legal meaning very different from their ordinary

meanings. Tiersma calls the legal vocabulary that looks

like ordinary language but which has a different

meaning peculiar to law as "legal homonyms"

(1999:112). This is one of the problematic features in

translation.

There are also synonyms in legal languages of both

Turkish and English, i.e., different words with the same

meaning. One of the features of legal language which

makes it difficult to understand and translate (for an

ordinary translator/reader) of course is its unusual and

technical vocabulary. Some of its vocabulary such as

"tortfeasor," "estoppel" in English and "ahzukabza"

(take and receive) in Turkish, which do not even

suggest a meaning to an ordinary person, is a complete

mystery to non-lawyers.

Another feature of the English legal language is the

modal verb "shall." In ordinary English, "shall" typically

expresses the future tense, while in English legal

language "shall" does not indicate futurity, but it is

employed to express a command or obligation (Tiersma

1999:105). However, in Turkish legal documents, the

way of expressing legal obligation is using simple

present tense.

Problems and Difficulties Encountered in

Translating Legal Texts Between English and

Turkish

Translation of legal texts (from English into Turkish and

visa versa) poses problems closely related to both the

nature of legal language and the specific features of

both English and Turkish legal systems and languages.

The examples that follow cover a wide range of legal

texts; from contracts to resolutions to treaties.

I) Problems arising due to the differences in legal

systems: The most daunting aspect of legal translation

common to almost every language is the culture-specific

quality of the texts. As Martin Weston suggests, "the

basic translation difficulty of overcoming conceptual

differences between languages becomes particularly

acute due to cultural and more specifically institutional

reasons (1983:207). Newmark also suggests that "a

word denoting an object, an institution, or if such exists,

a psychological characteristic peculiar to the source

language culture is always more or less untranslatable"

(quoted in Weston 1983:207). The equivalence of an

institution, a division, a concept, or a term may not be

found in the target language—in our case, in Turkish.

There are no words in Turkish to express some of the

most elementary notions of British law. The words

"common law" and "equity" are only two of the

examples. There is no system of "common law" and

"equity" in the Turkish legal system. Moreover how

should we translate "barrister" or "solicitor" into Turkish

as there are no such job titles in the Turkish legal

system. A Turkish legal translator overcomes the

difficulty of translating a term or a concept which is

absent in the target culture using the following

methods:

1) Paraphrasing

This method is explaining the SL concept if it is

unfamiliar to the target reader, when there is no

equivalent institution or concept in the target culture

and when a literal translation will make no sense.

As we have mentioned above, the translation of

"barrister" and "solicitor is problematic, since in the

Turkish legal system there are no such job titles. As we

know, in the British legal system a "barrister" is a

person who executes the legal case in courts, whereas

"solicitors" are those who declare their opinions and

recommendations to the parties in a lawsuit and who

provide contact with the barrister (Yalçınkaya

1981:153).

As a concept, 'barrister' is more or less the formal

equivalent of 'lawyer' in Turkey. To overcome the

conceptual confusion, barrister is translated as "duruş

ma avukatı," meaning the "lawyer in court," whereas

"the solicitor" is translated as "danış ma avukatı" which

means the "consultant lawyer."

This is paraphrasing the concepts which are not shared

both by the source and target cultures. Another

concept, which commonly causes translation problems

between different cultures, is "Lord Chancellor." Since

there is no "House of Commons" or "House of Lords" in

the Turkish parliamentary system, these terms are also

translated by paraphrasing. "Lord Chancellor" is

translated as "Lordlar Kamarası Baskanı" meaning the

"Head of the House of Lords." Concepts peculiar to the

Western legal and parliamentary systems are generally

translated through paraphrasing.

2) Finding the Functional Equivalence

This is using a TL expression that is the nearest

equivalent concept. Of course it is much more difficult to

find the functional equivalent of a legal SL term where

the legal institutions of two cultures do not have much

in common.

To quote an example that is problematic mostly for

translators between English and French: "Solicitor"

(which is used for the French "notaire") has the Turkish

functional equivalent of "notary." Moreover, the

generally used Turkish functional equivalent of

"solicitor" is "avukat" which is the literal translation of

"lawyer." Both "court" and "tribunal" are translated as

"mahkeme" which is the literal translation of "court."

Translation of "tribunal" as "mahkeme" is rendering the

functional equivalent of it.

Using this method frequently leaves the translator short

of terminology due to the different structures of the

legal systems of the Turkish and British cultures.

3) Word-for-Word (Literal) Translation

This is translating lexical word for lexical word, and

making adjustments of prepositions, endings, and other

grammatical features if necessary. For example, "Court

of Protection" is translated directly as "Koruma

Mahkemesi" (Koruma=Protection and Mahkeme=Court)

while the words change place so as to ensure the

correct syntactic arrangement in Turkish. Other

examples may include the translation of "Treasury

Solicitor" as "Hazine Avukatı" (Treasury=Hazine and

Solicitor= Avukat), "Courts of Chivalry" as "Şövalyelik

Mahkemesi" (Chivalry=Şövalyelik, Court= Mahkeme).

On the other hand, when the source text is in Turkish,

and when it is translated into English, it makes a

difference whether the target text is directed to

American or English culture, because the terms and

institutions of different cultures using the same

language may be different. For example, a "prison" in

the British System is a "penitentiary" in the American

system, and they are both translated as "hapishane"

into Turkish. A "Magistrate's Court" in the British legal

system is "Civil Court of Peace" in the American legal

system, and they are both translated as "Sulh

Mahkemesi" into Turkish. "Attorney" and "Sheriff" do

not have simple translated equivalents in UK English

and other languages (Rey 1995:88).

II) Problems arising due to the difference in the

language systems, syntactic arrangements, and word

orders of the Turkish and English languages:

A) The fact that the verb is placed at the beginning of a

sentence in English (SVO pattern), while it is placed at

the end of a sentence in Turkish (SOV pattern) creates

problems for the translator. The following sentences are

taken from the "Resolution adopted by 933 votes to 65,

with 356 abstentions by the 94th Inter-Parliamentary,

Conference (Bucharest, 13 October 1995), "To

Comprehensively Ban Nuclear Weapons Testing And Halt

All Present Nuclear Weapons Tests":

The 94th Inter-Parliamentary

Conference,

Hoping that these tests will not

complicate the already difficult

negotiations underway on a

comprehensive test ban treaty and

make it more difficult to achieve a

truly comprehensive and

internationally verifiable treaty,

Recalling that the Inter-Parliamentary,

Union has a duty to promote the

cause of international peace and

security, nuclear disarmament and the

non-proliferation of nuclear

weapons,...

The translation into Turkish is as follows:

Bu denemelerin nükleer silah

denemelerini yasaklayan kapsamlı bir

anlaşma için yapılmakta olan

meşakkatli görnşmeleri daha da

zorlastırmayacagını umarak

Parlementolararası Birliğin uluslar

arası barış ve güvenlik davasını,

nükleer silahsızlanmayı ve nükleer

silahların artışını engellemeyi

destekleme görevine sahip olduğunu

hatırlatarak

The underlined words, which are placed at the beginning

of the sentences in the source text, will automatically

shift to the end of the sentences in the translated text

which is in Turkish:

This difference in word orders of both languages can

also be visually explicit. The heading of the source text

is as follows:

RESOLUTION

On Economic and Trade Relations

Between the Community and Turkey.

However, the target text has the following arrangement:

Topluluk ve Türkiye Arasındaki

Ekonomik ve Ticari İlişkiler Üzerine

KARAR

As obvious, even the visual arrangement of the heading

shows great difference as the word "Resolution"

(meaning "Karar" in Turkish) is placed at the beginning

in the English text, while it is placed at the end in the

Turkish sentence.

B) Another difficulty arises due to the use of modal verb

"shall" in legal English. When they study the grammar of

the English language, Turkish students learn that "shall"

is the modal verb indicating futurity, and therefore they

tend to translate the sentences containing "shall" as

future tense into Turkish. However, as Danet suggests

(1985:281), in formal English legal language, "shall" is

used to express authority and obligation (Bowers

1989:35), rather than futurity.

The following is an example taken from the

Memorandum signed in Prague on 19 October 1989

between Czechoslovakia and Turkey:

Article 2:

"The Parties shall take the necessary

measures to ensure the mutual

facilitation of tourist flow in their

respective countries

Article 5:

"The parties shall exchange

information, technology and experts in

the field of tourism training."

The translation is as follows:

Madde 2:

"Taraflar kendi ulkelerinde turist

akısını karsılıklı olarak kolaylastırmayı

saglamak icin gerekli tedbirleri alırlar

(The parties take the necessary

measures...)."

Madde 5:

"Taraflar turizm eğitimi alanında

karşılıklı bilgi, teknoloji ve uzman

mübadelesinde."bulunurlar (The

parties exchange information)."

The verbs in bold letters are the verbs of both texts. The

source text uses the modal verb "shall," while the

correct translation uses the present tense.

III) Problems arising due to the lack of an established

terminology in Turkey in the field of law: Although the

terminographer Daniel Gouadec says that identifying

only one term for a specific concept, object, or situation

is impossible (1990:XVII), the necessity for each

subject field to describe, standardise, and teach its

terminology has now become evident in the age of ever

increasing international relationships.

The following examples, which are taken from The

Treaties Establishing the European Communities

(1996), and their translations, show that there may be

more than one counterpart in Turkish of a single word in

English:

1) Any European state may apply to

accede to this Treaty. It shall

address its application to the Council,

which shall act unanimously after

obtaining the opinion of the High

Authority; the council shall also

determine the terms of accession;

likewise acting unanimously.

Accession shall take effect on the day

when the instrument of accession is

received (Article 98).

The translation into Turkish is as follows:

1) Her Avrupa devleti işbu antlaşmaya

taraf olmak için başvuruda bulunabilir.

Antlaşmaya taraf olmak isteyen

devlet Konseye basvurur. Konsey,

Yüksek Otoritenin görüşünü aldıktan

sonra oybirligiyle karar alır ve yine

oybirliğiyle katılma şartlarını belirler.

Bu katılma katılma belgesinin işbu

antlaşmanın .......(Avrupa

Topluluklarını Kuran Temel

Antlaşmalar,1996, Madde:98).

As noted above, the verb "accede" is translated as

"taraf olmak," while its noun derivation "accession" is

rendered by a noun which is derived from a totally

different verb "katılmak" in Turkish. Thus two different

verbs which are "taraf olmak" and "katılmak" are used

in the target text for a single verb "access" in the source

text.

Another example is the following:

2)....to evade the rules of competition

instituted under this Treaty, in

particular by establishing an artificially

privileged position involving a

substantial advantage in access to

supplies or markets (Article 66) .

2)...özellikle ikmal kaynaklarından

veya pazarlardan yararlanmada

önemli bir avantaj elde edecek

şekilde....(Madde:66).

Unlike in article (1), the same English verb "access" is

rendered by a completely different Turkish verb

"yararlanma" which literally has the English

equivalence of "benefit from."

To elaborate on the examples and in order to indicate

how serious the issue is, let us take a look at some

more examples from the Translation into Turkish of the

"Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and

Fundamental Freedoms." Excerpts from the texts in

target and source languages are given below:

Article 5:

1. Everyone has the right to liberty and

security of person. No one shall be deprived

of his liberty save in the following cases and

in accordance with a procedure prescribed

by law:

a) The lawful detention of a person

after conviction by a competent court

b) The lawful arrest or detention of a

person.....

The translation into Turkish is as follows:

1).....

a) Salahiyetli her mahkeme tarafından

mahkumiyeti üzerine usulu

dairesinde hapsedilmesi

b) Bir mahkeme tarafından kanuna

uygun olarak verilen bir karara....

The adjectives "lawful" having exactly the same

meanings in the source text above are translated as

"usulu dairesinde" and "kanuna uygun olarak"

respectively in the target text, and these are official

translations.

IV) Problems due to the use of unusual sentence

structures in the English legal language: As Tiersma

suggests, there are various kinds of subjunctives, all of

which have died out in modern English, especially in

spoken language (1999:93). The type of "legal"

subjunctive is a construction known as the "formulaic

subjunctive" which involves use of a verb in its base

form and conveys roughly the same meanings as "let"

or "may." This usage, which Tiersma characterises as

formal and old fashioned, is still very much alive in legal

usage. The frequent phrase used at the beginning of a

Power of Attorney, "Know all men by these presents" is

a completely uncommon word order and uncommon

sentence structure. In a "Vekaletname" in Turkish,

which is the counterpart of a Power of Attorney, there is

no uncommon sentence structure as such, although the

general sentence structure of it resembles that of the

Power of Attorney with respect to its length and

complexity.

Another example is the "British enactment clause"

(Tiersma 1999:93), which is found at the beginning of

all statutes:

"Be it enacted by the Queen's most

Excellent Majesty, by and with the

advice and consent of the Lords

Spiritual and Temporal, and

Commons, in this present Parliament

assembled, and by the authority of the

same....."

In addition to the subjunctive, this clause illustrates

several other common features of legal English, such as

French word order (Lords Spiritual and Temporal),

formal language (Queen's most Excellent Majesty), odd

word order (in Parliament assembled), and conjoined

phrases (by and with, advice and consent) (Tiersma

1999:93), which are still very challenging features for a

Turkish legal translator.

V) The fifth main reason for the errors and difficulties in

the translation of legal texts is the fact that the

language used in the legal system in Turkey is very old

and generally quite different from the currently used

language for the reasons explained in the previous

chapters. There are still many words and patterns in

legal Turkish texts which are completely out of date in

other types of discourse.

The following terms are taken from the Contract signed

between the Public Airports Administration of the

Republic of Turkey and Company X for the purchase of

special material. These terms are completely in old

Turkish and are used nowhere else in Turkey presently

except in legal texts. Although they are not

understandable to a Western reader, it would be

interesting to see the difference between the old Turkish

words which still occur in legal texts and their modern

Turkish versions used in non-legal discourse. Their

English equivalents are given in parenthesis below:

Words in Old Turkish Modern Turkish

Versions

gayri kabili rücu geri dönülmez

(irrevocable)

muhabir banka bildirimci banka

(correspondent bank)

vecibe (obligation) yükümlülük

navlun (freight) gemi taşıma ücreti

sevk vesaiki (shipping gönderme belgesi

document)

We could provide many more examples. The old Turkish

used in the field of law not only makes the translation of

texts a hard task, but also hampers the instructor's

endeavours to teach translation in this field. It is

absolutely necessary that the current use of the old

words be taught to the translation students before

starting the actual translation process. The archaic

expressions found in legal English for reasons

mentioned in the previous chapters add to the problem.

These include: hereinafter, hereto, herein, hereby,

hereof, thereof, therein, thereby, thereto, etc. None of

them can be translated by a single word, and translators

often have a hard time finding equivalents for these

archaic expressions.

VI) Problems arising due to the use of common terms

with uncommon meanings: As Brenda Danet suggests,

"legal language has a penchant for using familiar words

(but) with uncommon meanings" (1985:279). Let us

take, as an example, the word "assignment" which is

generally known as "something assigned, a task or a

duty." Turkish students of translation have learnt the

word in its general literal meaning and they continue to

know it as such until they have to translate an

"assignment," which is a legal document. Of course, the

first thing they have to do is to search for the meaning

of "assignment" in a legal dictionary. The same applies

to the words "whereas" and "having regard to" among

many others. In legal documents such as contracts, the

above-mentioned words function as "considering" or

"taking into consideration," and must be so translated

into Turkish.

Conclusion

Sarcevic suggests that the traditional principle of fidelity

has recently been challenged by the introduction of new

bilingual drafting methods which have succeeded in

revolutionising legal translation. Contrary to freer forms

of translation, legal translators are still guided by the

principle of fidelity; however their first consideration is

no longer fidelity to the source text but to guarantee the

effectiveness of multilingual communication in the legal

field (1997:16).

While lawyers cannot expect translators to produce

parallel texts that are identical in meaning, they do

expect them to produce parallel text that are identical in

their legal effect. Thus the translator's main task is to

create a text that will produce the same legal effect in

practice. To do so, the translator must be able "to

understand not only what the words mean and what a

sentence means, but also what legal effect it is

supposed to have, and how to achieve that legal effect

in the other language (Sarcevic 1997:70-71).

Translators must be able to use legal language

effectively to express legal concepts in order to achieve

the desired effect. They must be familiar with the

conventional rules and styles of legal texts in every field

of the individual legal systems. A legal translator must

not forget that even a Will is not valid if not written in

the correct style.

References

AYITER, F. 1956 "The Interpretations of a National

System of Laws Received from Abroad," Annales de la

faculté de droit d'Istanbul . Istanbul:Fakülteler

Matbaası.

Avrupa Topluluklarını Kuran Temel Antlaşmalar. 1996.

T.C Başbakanlık D.P.T Yayınları.

BHATIA, V.K. 1983. Analysing Genre: Language Use in

Professional Settings. London: Longman.

BOWERS, Frederic. 1989 Linguistic Aspects of

Legislative Expressions. Vancouver; University of

Columbia Press.

Contract between The Public Airport Administration of

the Republic of Turkey and Company X.

Convention For the Protection of Human Rights and

Fundamental Freedoms.

DANET, Brenda. 1985. "Legal Discourse," Handbook of

Discourse Analysis. Vol.1 New York: Academic Press.

GOODRICH Peter. 1987. Legal Discourse. Hong Kong:

Mac Millan

GOUADEC, Daniel. 1990. Terminologie Constitution des

Donnés. Afnor: Paris.

HEYD, Uriel. 1954. Language Reform in Modern Turkey.

Jerusalem: Hadassah Apprentice School of Printing.

IZVEREN, Adil . 1956. "The Reception of the Swiss Civil

Code in Turkey," Annales de la Faculte de Droit

D'Istanbul. Istanbul: Fakülteler Matbaası.

MELINKOFF, David. 1963. The Language of the Law.

Boston: Little Brown

Memorandum between Czechoslovakia and Turkey.

October 1989.

MORRIS, Marshall (ed.) 1995. Translation and the Law.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins

NEWMARK, Peter. 1988. A Textbook of Translation.

London: Prentice Hall

Official Journal of the European Communities.

17.4.1989.

ÖZDEMIR, Emin. 1969." Yasaların Dili" (Language of

Law), Journal of TDK. Ankara: TDK Publucations.

Results of the Inter-Parliamentary Union. 94th

Conference and Related Meetings. 6-4 October 1995

Bucharest, Romania.

REY, Alain. 1995 Essays on Terminology. (ed. and tr.)

Juan C. Sager Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

SARCEVIC, Susan. 1997. New Approach to Legal

Translation. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

TIERSMA, Peter M. 1989. Linguistic Aspects of

Legislative Expression. Vancouver: University of British

Columbia Press.

TIMUR, Hıfzı.1956. "The Place of Islamic Law in Turkish

Law Reform," Annales de la Faculte de Droit D'Istanbul.

Istanbul: Fakülteler Matbaası.

Treaties Establishing the European Communities.

Abridged Edition

WESTON, Martin. 1983. "Problems and Principals in

Legal Translation," The Incorporated Linguist. Autumn,

Vol 22, No:4

YALÇINKAYA, Namık Kemal. 1981. Ingiliz Hukuku (The

British Law). Ankara: Eroglu Matbaası.

You might also like

- Peter Tiersma, Legal Language: (University of Chicago Press, 1999)Document18 pagesPeter Tiersma, Legal Language: (University of Chicago Press, 1999)RishiNo ratings yet

- Latin Pronunciation: A Short Exposition of the Roman MethodFrom EverandLatin Pronunciation: A Short Exposition of the Roman MethodNo ratings yet

- UTS Bahasa Inggris Hukum 2023Document31 pagesUTS Bahasa Inggris Hukum 2023Starla HemaNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of the English Language and Literature, Vol. 2From EverandA Brief History of the English Language and Literature, Vol. 2No ratings yet

- Nature of Legal LanguageDocument18 pagesNature of Legal LanguageRahulNo ratings yet

- PDF 92522 28114Document10 pagesPDF 92522 28114YASH PANDEYNo ratings yet

- Index 2-2Document12 pagesIndex 2-2Akshat AnandNo ratings yet

- Legal Language Peter TiersmaDocument21 pagesLegal Language Peter TiersmaVen Viv Gumpic100% (3)

- CH II DisertatieDocument10 pagesCH II DisertatiemirabikaNo ratings yet

- The Heritage of Legal Latin in Europe: The Twelve Tables - Was The Ancient Legislation That Stood at The Foundation ofDocument8 pagesThe Heritage of Legal Latin in Europe: The Twelve Tables - Was The Ancient Legislation That Stood at The Foundation ofCorina AlinaNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Legal LanguageDocument26 pagesThe Origins of Legal LanguageSilvina PezzettaNo ratings yet

- Refrence CodesDocument11 pagesRefrence CodesJonNo ratings yet

- Syntactic Properties of Legal Language in English and AlbanianDocument5 pagesSyntactic Properties of Legal Language in English and AlbanianTrúc PhạmNo ratings yet

- Iind Semester Unit 2: InroductionDocument13 pagesIind Semester Unit 2: InroductionS DastagiriNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument10 pages1 SMzemikeNo ratings yet

- الترجمة القانونية بين النظرية والتطبيق محمد يوسف سوسن عبود PDFDocument25 pagesالترجمة القانونية بين النظرية والتطبيق محمد يوسف سوسن عبود PDFMohammad A Yousef100% (4)

- LJBJDocument15 pagesLJBJDoo RaNo ratings yet

- Module 01 - Law & Language, Origin & Scope of Legal LanguageDocument9 pagesModule 01 - Law & Language, Origin & Scope of Legal LanguageS DalviNo ratings yet

- Development of Legal English-967Document3 pagesDevelopment of Legal English-967Helen castro ;3No ratings yet

- The Main Characteristics of Legal English-Mykhailova O.V PDFDocument4 pagesThe Main Characteristics of Legal English-Mykhailova O.V PDFManar MoslemNo ratings yet

- The Fall and Rise of English in Common LawDocument16 pagesThe Fall and Rise of English in Common LawandreaNo ratings yet

- Termpaper Sociolinguistics1Document12 pagesTermpaper Sociolinguistics1BASHAR BINJINo ratings yet

- ConclusionsDocument2 pagesConclusionsCorina AlinaNo ratings yet

- Legal EnglishDocument18 pagesLegal EnglishvishnuNo ratings yet

- Legal English....Document6 pagesLegal English....Mohamed AbulineinNo ratings yet

- Evolution Legal LanguageDocument50 pagesEvolution Legal LanguageEwa HelinskaNo ratings yet

- Methodology + Legal EnglishDocument6 pagesMethodology + Legal EnglishvolodymyrNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Legal Language DevelopmentDocument6 pagesA Review of The Legal Language DevelopmentTrúc PhạmNo ratings yet

- Legal English - Origin and LegaleseDocument31 pagesLegal English - Origin and LegaleseRahul BirabaraNo ratings yet

- 3rd Sem Eng Assignment WordDocument2 pages3rd Sem Eng Assignment WordSmuggy LampNo ratings yet

- 1.1 The Anglo-Saxon Period The English Language Can Be Said To Have Begun Around 450 A.D., When Boats LoadsDocument6 pages1.1 The Anglo-Saxon Period The English Language Can Be Said To Have Begun Around 450 A.D., When Boats LoadsCorina AlinaNo ratings yet

- Origins of English Legal LanguageDocument3 pagesOrigins of English Legal LanguagePhillip Ellington0% (1)

- Our Laws Are As Mixed As Our Language': Commentaries On The Laws of England and Ireland, 1704-1804Document19 pagesOur Laws Are As Mixed As Our Language': Commentaries On The Laws of England and Ireland, 1704-1804MichaelNo ratings yet

- 05 Bates L. HofferDocument20 pages05 Bates L. HofferHarun Rashid100% (1)

- юююDocument3 pagesюююСнежана ДемченкоNo ratings yet

- Court, Parliament, Justice, Sovereign and Marriage Come From This PeriodDocument119 pagesCourt, Parliament, Justice, Sovereign and Marriage Come From This PeriodLan Anh HoaNo ratings yet

- Is Legal Lexis A Characteristic of Legal Language?Document15 pagesIs Legal Lexis A Characteristic of Legal Language?ayushNo ratings yet

- Legal Language:Origin, Nature and ScopeDocument20 pagesLegal Language:Origin, Nature and ScopeSaquib khanNo ratings yet

- LatinDocument121 pagesLatinOmid DjalaliNo ratings yet

- What Is Language and Law and Does Any-1Document17 pagesWhat Is Language and Law and Does Any-1Mayank YadavNo ratings yet

- Legal Language:Origin, Nature and ScopeDocument20 pagesLegal Language:Origin, Nature and ScopeAnas AliNo ratings yet

- "The Pleading in English ACT 1362": Profesorado de Inglés 2° 2°Document7 pages"The Pleading in English ACT 1362": Profesorado de Inglés 2° 2°Ana PaezNo ratings yet

- Lexicology With Etymology First AssignmentDocument7 pagesLexicology With Etymology First AssignmentGashi ArianitNo ratings yet

- History of Legal WritingDocument4 pagesHistory of Legal WritingFrank FranticNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Legal Speech Acts in English Contract LAWDocument26 pagesAn Analysis of Legal Speech Acts in English Contract LAWMuhammad AdekNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - An Expanded Definition of The Language of The LawDocument3 pagesChapter 1 - An Expanded Definition of The Language of The LawKD100% (1)

- Historical Aspects of Court InterpretingDocument41 pagesHistorical Aspects of Court InterpretingRyanPesiganReyesNo ratings yet

- Calrity and Obscurity in Legal LanguageDocument6 pagesCalrity and Obscurity in Legal LanguageHarsh MankarNo ratings yet

- Law ManuscriptDocument56 pagesLaw ManuscriptInaNo ratings yet

- Language Varieties and Standard LanguageDocument9 pagesLanguage Varieties and Standard LanguageEduardoNo ratings yet

- Lectura de Derecho en InglésDocument1 pageLectura de Derecho en InglésKrysium moonbladeNo ratings yet

- Williams - Legal English and Plain Language. An IntroductionDocument14 pagesWilliams - Legal English and Plain Language. An IntroductionryvertNo ratings yet

- Guest Post by Rochelle CeiraDocument12 pagesGuest Post by Rochelle CeiraRuby P. LongakitNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument6 pagesReportjennyrbss84No ratings yet

- LECTURE Monday 17th May 2021Document5 pagesLECTURE Monday 17th May 2021irenetiradomarNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of The English Language - Final Version With Study GuideDocument8 pagesA Brief History of The English Language - Final Version With Study GuideRaul Quiroga100% (1)

- Thesis Steven Boer 11 NovDocument44 pagesThesis Steven Boer 11 NovBianca SferleNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Role Play (Students) : 1. SituationDocument1 pageGuidelines For Role Play (Students) : 1. SituationJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Translation of Documents Required To Obtain Nationality in EU CountriesDocument1 pageTranslation of Documents Required To Obtain Nationality in EU CountriesJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Escort AirportDocument1 pageEscort AirportJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines - Students - Presentations FilmDocument2 pagesGuidelines - Students - Presentations FilmJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Latvian Court System: Ventspils University College Anita Kazina Linda Fominiha Linda Nececka Agnese Štāla Laura LiepiņaDocument15 pagesLatvian Court System: Ventspils University College Anita Kazina Linda Fominiha Linda Nececka Agnese Štāla Laura LiepiņaJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Portuguese Judicial SystemDocument26 pagesPortuguese Judicial SystemJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Entry Skilled Professionals - ENDocument4 pagesEntry Skilled Professionals - ENJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Recensao - Women and LanguageDocument4 pagesRecensao - Women and LanguageJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Amadeus - ManualDocument16 pagesAmadeus - ManualPathanblr100% (1)

- 2014 Conf Progr AbstractsDocument17 pages2014 Conf Progr AbstractsJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Workshop Cultura VisualDocument1 pageWorkshop Cultura VisualJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Review Ellipsis Journal of The American Portuguese Studies AssociationDocument4 pagesReview Ellipsis Journal of The American Portuguese Studies AssociationJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Viii Conference Cycle, 2014-2015 Centre For Intercultural StudiesDocument1 pageViii Conference Cycle, 2014-2015 Centre For Intercultural StudiesJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Mulmaster Bonds and BackgroundsDocument6 pagesMulmaster Bonds and BackgroundsJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- Centre For Intercultural Studies WWW - Iscap.ipp - Pt/cei: Presentation and ObjectivesDocument2 pagesCentre For Intercultural Studies WWW - Iscap.ipp - Pt/cei: Presentation and ObjectivesJorge NunoNo ratings yet

- SW Saga The Unknown RegionsDocument226 pagesSW Saga The Unknown RegionsBarbie Lees100% (7)

- 5E D&D ToD Character Sheet v2 (Form)Document2 pages5E D&D ToD Character Sheet v2 (Form)Omar Rodriguez100% (2)

- D&D Adventurer's League Adventure LogsheetDocument1 pageD&D Adventurer's League Adventure LogsheetChristopher PlambeckNo ratings yet

- Indus River Valley CivilizationDocument76 pagesIndus River Valley CivilizationshilpiNo ratings yet

- Asian Contemporary Art in JapanDocument7 pagesAsian Contemporary Art in Japanvekjeet ChampNo ratings yet

- Constructing A Replacement For The Soul - BourbonDocument258 pagesConstructing A Replacement For The Soul - BourbonInteresting ResearchNo ratings yet

- Learning Episode 2Document9 pagesLearning Episode 2Erna Vie ChavezNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudential Analysis of Nirbhaya Rape CaseDocument25 pagesJurisprudential Analysis of Nirbhaya Rape CaseAishwarya Ravikhumar67% (3)

- Consumer Production in Social Media Networks: A Case Study of The "Instagram" Iphone AppDocument86 pagesConsumer Production in Social Media Networks: A Case Study of The "Instagram" Iphone AppZack McCune100% (1)

- The Role of Philosophy in Curriculum DevelopmentDocument18 pagesThe Role of Philosophy in Curriculum DevelopmentZonaeidZaman68% (19)

- Maintenance in Muslim LawDocument11 pagesMaintenance in Muslim LawhimanshuNo ratings yet

- Chapter I234Document28 pagesChapter I234petor fiegelNo ratings yet

- U4Ca & Tam Rubric in CanvasDocument3 pagesU4Ca & Tam Rubric in CanvasOmar sarmiento100% (1)

- Short Exploration of Madame Duval's Character in Frances Burney's Evelina (Jan. 2005? Scanned)Document2 pagesShort Exploration of Madame Duval's Character in Frances Burney's Evelina (Jan. 2005? Scanned)Patrick McEvoy-Halston100% (1)

- Sid ResumeDocument2 pagesSid ResumeBikash Ranjan SahuNo ratings yet

- Siop Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesSiop Lesson Planapi-475024988No ratings yet

- Influencing Factors of Cosplay To The Negrense YouthDocument44 pagesInfluencing Factors of Cosplay To The Negrense YouthMimiNo ratings yet

- Elpida Palaiokrassa & Aris FoufasDocument18 pagesElpida Palaiokrassa & Aris FoufasNicu BalanNo ratings yet

- Earthquake Event Media Release - 2Document2 pagesEarthquake Event Media Release - 2Lovefor ChristchurchNo ratings yet

- Dolores Huerta Primary and Secondary SourcesDocument6 pagesDolores Huerta Primary and Secondary Sourcesapi-393875200No ratings yet

- Communicative Competence: Brown, H.D (1994) Principles of Language Teaching andDocument16 pagesCommunicative Competence: Brown, H.D (1994) Principles of Language Teaching andLuciaNo ratings yet

- Graphic Organizer Chapter 14 - Interactional SociolinguisticsDocument4 pagesGraphic Organizer Chapter 14 - Interactional Sociolinguisticsevelyn f. mascunanaNo ratings yet

- Character: The Seven Key Elements of FictionDocument5 pagesCharacter: The Seven Key Elements of FictionKlint VanNo ratings yet

- English Vocabulary Exercises LIFE STAGES 2022Document3 pagesEnglish Vocabulary Exercises LIFE STAGES 2022daniela BroccardoNo ratings yet

- In Collaboration With: Itf-Model Skills Training Centre (Itf-Mstc), AbujaDocument2 pagesIn Collaboration With: Itf-Model Skills Training Centre (Itf-Mstc), AbujaFatimah SaniNo ratings yet

- Resumen INEN 439Document7 pagesResumen INEN 439Bryan RamosNo ratings yet

- Engerman - Review of The Business of Slavery and The Rise of American CapitalismDocument7 pagesEngerman - Review of The Business of Slavery and The Rise of American CapitalismGautam HazarikaNo ratings yet

- 2nd Year English Essays Notes PDFDocument21 pages2nd Year English Essays Notes PDFRana Bilal100% (1)

- Group 2Document19 pagesGroup 2Marjorie O. MalinaoNo ratings yet

- Science and Its TimesDocument512 pagesScience and Its Timesluis peixotoNo ratings yet

- Essential Polymeter Studies in 4/4:: The ConceptDocument8 pagesEssential Polymeter Studies in 4/4:: The ConceptMalik ANo ratings yet

- CV Kashif AliDocument2 pagesCV Kashif AliRao KashifNo ratings yet

- Ge Sem - 4 - Indological Perspective - G S GhureyDocument10 pagesGe Sem - 4 - Indological Perspective - G S GhureyTero BajeNo ratings yet

- Wild and Free Book Club: 28 Activities to Make Books Come AliveFrom EverandWild and Free Book Club: 28 Activities to Make Books Come AliveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Read-Aloud Family: Making Meaningful and Lasting Connections with Your KidsFrom EverandThe Read-Aloud Family: Making Meaningful and Lasting Connections with Your KidsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (205)

- Empires of the Word: A Language History of the WorldFrom EverandEmpires of the Word: A Language History of the WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (236)

- Uncovering the Logic of English: A Common-Sense Approach to Reading, Spelling, and LiteracyFrom EverandUncovering the Logic of English: A Common-Sense Approach to Reading, Spelling, and LiteracyNo ratings yet

- The Read-Aloud Family: Making Meaningful and Lasting Connections with Your KidsFrom EverandThe Read-Aloud Family: Making Meaningful and Lasting Connections with Your KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Proven Speed Reading Techniques: Read More Than 300 Pages in 1 Hour. A Guide for Beginners on How to Read Faster With Comprehension (Includes Advanced Learning Exercises)From EverandProven Speed Reading Techniques: Read More Than 300 Pages in 1 Hour. A Guide for Beginners on How to Read Faster With Comprehension (Includes Advanced Learning Exercises)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- How to Read Poetry Like a Professor: A Quippy and Sonorous Guide to VerseFrom EverandHow to Read Poetry Like a Professor: A Quippy and Sonorous Guide to VerseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (56)

- 100 Days to Better English Reading Comprehension: Intermediate-Advanced ESL Reading and Vocabulary LessonsFrom Everand100 Days to Better English Reading Comprehension: Intermediate-Advanced ESL Reading and Vocabulary LessonsNo ratings yet

- Differentiated Reading for Comprehension, Grade 2From EverandDifferentiated Reading for Comprehension, Grade 2Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Novel Study)From EverandHarry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Novel Study)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (6)

- Teach Reading with Orton-Gillingham: 72 Classroom-Ready Lessons to Help Struggling Readers and Students with Dyslexia Learn to Love ReadingFrom EverandTeach Reading with Orton-Gillingham: 72 Classroom-Ready Lessons to Help Struggling Readers and Students with Dyslexia Learn to Love ReadingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Honey for a Child's Heart Updated and Expanded: The Imaginative Use of Books in Family LifeFrom EverandHoney for a Child's Heart Updated and Expanded: The Imaginative Use of Books in Family LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Sight Words 3rd Grade Workbook (Baby Professor Learning Books)From EverandSight Words 3rd Grade Workbook (Baby Professor Learning Books)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Essential Phonics For Adults To Learn English Fast: The Only Literacy Program You Will Need to Learn to Read QuicklyFrom EverandEssential Phonics For Adults To Learn English Fast: The Only Literacy Program You Will Need to Learn to Read QuicklyNo ratings yet

- The Book Whisperer: Awakening the Inner Reader in Every ChildFrom EverandThe Book Whisperer: Awakening the Inner Reader in Every ChildRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- Phonics Pathways: Clear Steps to Easy Reading and Perfect SpellingFrom EverandPhonics Pathways: Clear Steps to Easy Reading and Perfect SpellingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- The Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind ReadsFrom EverandThe Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind ReadsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)