Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Curriculum Srtudies in Brazil

Curriculum Srtudies in Brazil

Uploaded by

Gladys JorgeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Curriculum Srtudies in Brazil

Curriculum Srtudies in Brazil

Uploaded by

Gladys JorgeCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 1

Curriculum Studies in Brazil:

An Overview

Ashwani Kumar

Introduction

Brazilian curriculum studies can be roughly divided into three phases:

Pre-Marxist (1950s–1970s); Marxist (1980s–mid-1990s); and Post-Marxist

(mid-1990s–present). The pre-Marxist phase is not discussed but referenced

in the chapters that follow; it was dominated by a Tylerian instrumentalism

variously depicted as positivist, behaviorist, technocratic, administrative,

and/or scientific (see Macedo’s chapter 7 of this volume1). The Marxist

phase focused on school-society relationship employing concepts such as

power, ideology, hegemony, and reproduction. Marxism—characterized

by emphases upon subjectivity, everyday life, hybridity, and multicultural-

ism—dominated the Brazilian field until the mid-1990s when postmod-

ern, poststructural, and postcolonial discourses replaced it.

In the following sections I turn to discuss in detail the nature of curricu-

lum discourses in Brazil during the Marxist and the Post-Marxist periods.

I must point it out here that by no means these are sharp divisions; indeed,

there is a coexistence of various discourses (positivist, Marxist, and post-

Marxist). But such periodization does reflect general trends. Moreover, as

an outsider to Brazilian curriculum theory and guided by Elba Siqueira de

Sá Barretto’s (chapter 4 of this volume) remark pinpointing “the lack of

research on the historical perspective of the curriculum [in Brazil],” such

an organization helped me organize the intellectual history of the field.

W. F. Pinar (ed.), Curriculum Studies in Brazil

© William F. Pinar 2011

28 ASHWANI KUMAR

Marxism (1980s–mid-1990s)

The New Sociology of Education, and the critical theories on curriculum

as a whole shifted the discussions, until then prevailing in the psycho-

pedagogy field, to issues of power, ideology and culture . . .

Elba Siqueira de Sá Barretto (chapter 4 of this volume)

During the 1960s and 1970s Brazil was in a great political turmoil char-

acterized by underdevelopment, imperialism, and the widely felt need for

structural reforms. There was as well intense hope that a socialist revolu-

tion would create a more just and equal society in the country (chapter 4).

This period was also characterized by debates on the relations between

education and social development. Notably, the links between education

and social development had already been the subject of attention of sociolo-

gists, among them Florestan Fernandes, Otávio Ianni, Fernando Henrique

Cardoso, and Luiz Pereira, who focused especially on urbanization and

industrialization. The importation of sociological perspectives represented

a new focus in the educational field, which had been marked by “psycho-

pedagogical studies” (chapter 4).

During the late 1970s and early 1980s scholarly production in cur-

riculum studies was not extensive. An article by José Luis Domingues,

based on the ideas of Habermas, was one of the first works articulating

the main curriculum categories of technical-linear, circular-consensual,

and dynamic-dialogical. At that time, only the texts by Michael Apple

and Henry Giroux had been published in Brazil. Abraham Magendzo’s

Curriculum e Cultura na América Latina [Curriculum and Culture in

Latin America] was also an important reference for the first courses intro-

duced in Brazil (chapter 4). Antonio Flávio Barbosa Moreira’s Currículos

e programas no Brasil [Curricula and Programs in Brazil] became a key,

indeed, canonical text.

During the first half of the 1990s, articles on the New Sociology of

Education, then a subject little known to Brazilians, began to circulate,

introduced by Brazilian scholars who had obtained their doctoral degrees

in the United Kingdom, among them Antônio Flávio and Lucíola Licínio

dos Santos (chapter 4). Such critical scholarship focused on the selection

and distribution of school knowledge, an attempt “to understand relation-

ships between the processes of selection, distribution and organization and

teaching of school contents and the strategies of power inside the inclusive

social context” (chapter 4). In their Currículo, cultura e sociedade, Moreira

and Silva defined curriculum as school content; they also identified ide-

ology, power, and culture as the main themes of the curriculum theory.

You might also like

- Edld 7432 History of Higher EducationDocument10 pagesEdld 7432 History of Higher Educationapi-257553260No ratings yet

- The Gift of The Magi Worksheets PDFDocument3 pagesThe Gift of The Magi Worksheets PDFAnonymous p1txoupQGvNo ratings yet

- Craig Batty Eds. Screenwriters and Screenwriting Putting Practice Into ContextDocument314 pagesCraig Batty Eds. Screenwriters and Screenwriting Putting Practice Into ContextDaiana NorinaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - Staging Your Play PDFDocument7 pagesLesson Plan - Staging Your Play PDFAnonymous iuQbQx9rJ50% (2)

- BRAGA Et Al. Public SociologyDocument10 pagesBRAGA Et Al. Public SociologyMarco Antonio GavérioNo ratings yet

- Luke Chapter 9Document9 pagesLuke Chapter 9Raúl MolinaresNo ratings yet

- The - Social - Sciences - in - The - Philippines - Reflections - On - Trends - and - Developments PDFDocument29 pagesThe - Social - Sciences - in - The - Philippines - Reflections - On - Trends - and - Developments PDFAlyssa CalumayanNo ratings yet

- Porio, Emma. 2009. Sociology Society and The State Institutionalizing Sociological Practice in The Philippines PDFDocument11 pagesPorio, Emma. 2009. Sociology Society and The State Institutionalizing Sociological Practice in The Philippines PDFPurpleBookLover14No ratings yet

- An Analysis of Pedagogy of The Oppressed by Paulo FreireDocument12 pagesAn Analysis of Pedagogy of The Oppressed by Paulo FreireRoy Java Villasor80% (5)

- Sociology, Society and The State: Institutionalizing Sociological Practice in The PhilippinesDocument12 pagesSociology, Society and The State: Institutionalizing Sociological Practice in The PhilippinesGiovanni LorchaNo ratings yet

- SIERRA, Gerónimo De. Social Sciences in Uruguay. (2005)Document48 pagesSIERRA, Gerónimo De. Social Sciences in Uruguay. (2005)EmersonNo ratings yet

- 20 BernsteinDocument22 pages20 BernsteinswanvriNo ratings yet

- Monte Mór, 2013Document24 pagesMonte Mór, 2013Thais MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Bautista On Philippine Sociology 1990sDocument25 pagesBautista On Philippine Sociology 1990sDebbie Manalili100% (2)

- Journals PPSJ 33 2 Article-P255 12-PreviewDocument2 pagesJournals PPSJ 33 2 Article-P255 12-PreviewCjES EvaristoNo ratings yet

- El Impacto Del Marxismo en La Sociologia NorteamericanaDocument32 pagesEl Impacto Del Marxismo en La Sociologia NorteamericanaRubén AnaníasNo ratings yet

- Marxist Historiography in The History of Education From Colonial To Neocolonial Schooling in The United StatesDocument55 pagesMarxist Historiography in The History of Education From Colonial To Neocolonial Schooling in The United StatesPrabhu AwasthiNo ratings yet

- Bautista, Maria Cynthia. 1994. "Reflections On Philippine Sociology in The 1990s." in Journal of Philippine Development, 38 (21) - 2-20 PDFDocument25 pagesBautista, Maria Cynthia. 1994. "Reflections On Philippine Sociology in The 1990s." in Journal of Philippine Development, 38 (21) - 2-20 PDFPurpleBookLover14No ratings yet

- ReconstructionismDocument24 pagesReconstructionismmjhamoyNo ratings yet

- Marxism and Adult EducationDocument15 pagesMarxism and Adult EducationCorina EchavarriaNo ratings yet

- Overview of MarxismDocument19 pagesOverview of MarxismOmonode O Drake OmamsNo ratings yet

- Anarchism Utopias and Philosophy of Educ PDFDocument20 pagesAnarchism Utopias and Philosophy of Educ PDFCabra CobraNo ratings yet

- The Social SciencesDocument35 pagesThe Social Sciencesimpacto0909No ratings yet

- Marxism and EducationDocument5 pagesMarxism and EducationCharisse LogronoNo ratings yet

- Chapter Seven Millan April 27Document33 pagesChapter Seven Millan April 27millamarNo ratings yet

- Towards A New Chile Through The Heart AsDocument18 pagesTowards A New Chile Through The Heart AslancelotdellagoNo ratings yet

- Ivan IllichDocument14 pagesIvan IllichAnja KofferNo ratings yet

- The Blue Collar Theoretically - John F LavelleDocument288 pagesThe Blue Collar Theoretically - John F LavelleawangbawangNo ratings yet

- Paulo Freire Beyond Adult LiteracyDocument15 pagesPaulo Freire Beyond Adult LiteracyCristiane ParenteNo ratings yet

- Reflections of Social Theory in IndiaDocument25 pagesReflections of Social Theory in IndiaAnjana RaghavanNo ratings yet

- Morrow-Rethinking Freire's OppressedDocument17 pagesMorrow-Rethinking Freire's OppressedRaymondAllenMorrowNo ratings yet

- Abraham DeLeonDocument19 pagesAbraham DeLeonIrini PapachristouNo ratings yet

- Roseberry - The Unbearable Lightness of AnthropologyDocument21 pagesRoseberry - The Unbearable Lightness of AnthropologyJLNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Controlandpower Thepoliticsofeducationunderburma Smilitarydictatorship1Document324 pagesKnowledge Controlandpower Thepoliticsofeducationunderburma Smilitarydictatorship1ေအာင္ ေက်ာ္ စြာNo ratings yet

- Toward A Class Cultural TheoryDocument34 pagesToward A Class Cultural TheoryJaime Omar SalinasNo ratings yet

- Etienne Balibar in Conversation: Revisiting European MarxismDocument17 pagesEtienne Balibar in Conversation: Revisiting European Marxismbordiga100% (1)

- Critical Social TheoryDocument16 pagesCritical Social Theorykeen brian arguellesNo ratings yet

- 667f PDFDocument9 pages667f PDFMuhammad ZahidNo ratings yet

- 667f PDFDocument9 pages667f PDFGustavo SevillaNo ratings yet

- Sociology and The Social Sciences in The Philippines: Developments and ProspectsDocument10 pagesSociology and The Social Sciences in The Philippines: Developments and ProspectsNoemi Lorenzana MapagdalitaNo ratings yet

- Owftrd Ri-Hierftrchilfttion: Chfti?Ter OneDocument14 pagesOwftrd Ri-Hierftrchilfttion: Chfti?Ter OneJanmejay SinghNo ratings yet

- Latin American Sociology's Contribution SOCIOLOGY in ProgressDocument36 pagesLatin American Sociology's Contribution SOCIOLOGY in ProgressJoséVicenteTavaresDosSantosNo ratings yet

- ARRUDA - hallEWEL. Sociology of FlorestanDocument14 pagesARRUDA - hallEWEL. Sociology of FlorestanLucasTrindade88No ratings yet

- Teaching Approaches in Social Studies 1Document5 pagesTeaching Approaches in Social Studies 1Jasher JoseNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy Origin, Vision, Action Ando ConsequencesDocument10 pagesCritical Pedagogy Origin, Vision, Action Ando ConsequencesSÍNDY MARCELA TABORDA PEÑANo ratings yet

- ED 815 - Book ReviewDocument2 pagesED 815 - Book ReviewCharles Jayson OropesaNo ratings yet

- Paulo Freire's Notion of Oppression, Conscientization and Revolution (Franz Giuseppe Cortez)Document4 pagesPaulo Freire's Notion of Oppression, Conscientization and Revolution (Franz Giuseppe Cortez)JustinBellaNo ratings yet

- Pemikiran Karl Marx 1Document28 pagesPemikiran Karl Marx 1Luviana dewiNo ratings yet

- Pedagogy of The OppressedDocument4 pagesPedagogy of The Oppressedmoschub100% (1)

- Paulo FreireDocument7 pagesPaulo FreireroblagrNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Philosophy of Education Within Educational Studies - J.R. MuirDocument26 pagesThe Evolution of Philosophy of Education Within Educational Studies - J.R. MuirBryan D GoertzNo ratings yet

- Marxism ResurgentDocument15 pagesMarxism ResurgentMaki65No ratings yet

- David Mills, Mustafa Babiker and Mwenda Ntarangwi: Introduction: Histories of Training, Ethnographies of PracticeDocument41 pagesDavid Mills, Mustafa Babiker and Mwenda Ntarangwi: Introduction: Histories of Training, Ethnographies of PracticeFernanda Kalianny MartinsNo ratings yet

- Text 1 Part 1Document4 pagesText 1 Part 1noelia lescanoNo ratings yet

- Capturing The Gramscian Project in Critical Pedagogy: Towards A Philosophy of Praxis in EducationDocument23 pagesCapturing The Gramscian Project in Critical Pedagogy: Towards A Philosophy of Praxis in EducationKARL MARXNo ratings yet

- 2 Introduction EERJ 12 2 WebDocument10 pages2 Introduction EERJ 12 2 WebLeonardo AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Marcuse's Challenges To EducationDocument5 pagesMarcuse's Challenges To EducationMadu BiruNo ratings yet

- Fieldwork Is Not What It Used to Be: Learning Anthropology's Method in a Time of TransitionFrom EverandFieldwork Is Not What It Used to Be: Learning Anthropology's Method in a Time of TransitionNo ratings yet

- Acha 2019 Ernesto Laclauandthe National LeftDocument33 pagesAcha 2019 Ernesto Laclauandthe National LeftLuca ZaidanNo ratings yet

- Artaraz - 2005 - El Ejercicio de PensarDocument19 pagesArtaraz - 2005 - El Ejercicio de PensarIgor MarquezineNo ratings yet

- Ernesto LaclauDocument4 pagesErnesto LaclauAnonymous j5B2CZNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy & Teaching English To Children: Group 5Document9 pagesCritical Pedagogy & Teaching English To Children: Group 5Siti Nawang WulanNo ratings yet

- 6-Module 6.1Document5 pages6-Module 6.1Juneil CortejosNo ratings yet

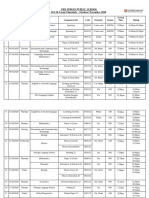

- The Indian Public School IGCSE Exam Timetable - October/ November 2020Document3 pagesThe Indian Public School IGCSE Exam Timetable - October/ November 2020Kumanan 1652005No ratings yet

- Eapp Handout 3Document8 pagesEapp Handout 3Zairah Jae GodilanoNo ratings yet

- Grapeseed Research ReportDocument12 pagesGrapeseed Research ReportKiều Ngọc OanhNo ratings yet

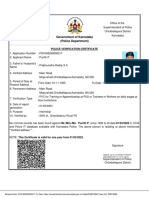

- PO016S230005217Document1 pagePO016S230005217Rok EyNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 - Practice 1Document3 pagesUnit 4 - Practice 1Nguyễn DuyênNo ratings yet

- Mircea Eliade Between The History of Rel PDFDocument205 pagesMircea Eliade Between The History of Rel PDFLarisaOniga100% (2)

- English k-10 SyllabusDocument227 pagesEnglish k-10 Syllabuslan100% (1)

- Gamification in Education 2Document8 pagesGamification in Education 2Kimberly McdonaldNo ratings yet

- An Intensive Course in Tamil - Dialogues, Drills, Exercises, Vocabulary, Grammar, and Word Index-Central Institute of Indian Languages (1979) - (CIIL Intensive Course Series, 2) S RajaramDocument873 pagesAn Intensive Course in Tamil - Dialogues, Drills, Exercises, Vocabulary, Grammar, and Word Index-Central Institute of Indian Languages (1979) - (CIIL Intensive Course Series, 2) S RajaramNeha Naik100% (4)

- Life of Christ Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesLife of Christ Reflection Paperapi-284304444No ratings yet

- Siop Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesSiop Lesson Planapi-475024988No ratings yet

- Assignment Ele3103Document14 pagesAssignment Ele3103Yizhar EfendyNo ratings yet

- Personal Data Sheet: Magaru Demy Bueno 11/4/1994Document11 pagesPersonal Data Sheet: Magaru Demy Bueno 11/4/1994Demy MagaruNo ratings yet

- Outwitting The Crocodile PresentationDocument28 pagesOutwitting The Crocodile PresentationEthel Marie Casido Burce76% (17)

- Prof. Madya DR Hj. Noor Shah Bin HJ SaadDocument17 pagesProf. Madya DR Hj. Noor Shah Bin HJ SaadMya SumitraNo ratings yet

- Iet Report Pavithra NewDocument80 pagesIet Report Pavithra NewPriyaNo ratings yet

- Table of SpecificationDocument6 pagesTable of SpecificationDin Flores MacawiliNo ratings yet

- Soft Skills Interview Chapter# 6Document23 pagesSoft Skills Interview Chapter# 6Sayed Waheedullah MansoorNo ratings yet

- Managing Self and Teams - Course OutlineDocument9 pagesManaging Self and Teams - Course OutlineRishabh MishraNo ratings yet

- Part 3 Human Process Interventions: Results of Intergroup Conflict InterventionsDocument2 pagesPart 3 Human Process Interventions: Results of Intergroup Conflict InterventionsRifky Dwi HendrawanNo ratings yet

- BECGDocument80 pagesBECGNikunj BhalodiNo ratings yet

- Basic Education Department 2 Quarter: School Year 2020-2021Document8 pagesBasic Education Department 2 Quarter: School Year 2020-2021Joshua ApolonioNo ratings yet

- Cultural StrategiesDocument26 pagesCultural StrategiesDeepshikha BhowmickNo ratings yet

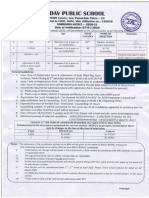

- DAV BSEB Admission 2020 FinalDocument1 pageDAV BSEB Admission 2020 FinalShivam ShreshthaNo ratings yet

- GS Form 101 - Thesis/Dissertation Topic ApprovalDocument2 pagesGS Form 101 - Thesis/Dissertation Topic ApprovalSyrile MangudangNo ratings yet

- ODCPL Information: 416 James Street Ozark, Alabama 36360Document4 pagesODCPL Information: 416 James Street Ozark, Alabama 36360odcplNo ratings yet

- Scholarly Research Journal'sDocument13 pagesScholarly Research Journal'sAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet