Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Futures Studies Art or Science-140111 - 041430

Futures Studies Art or Science-140111 - 041430

Uploaded by

faizalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Futures Studies Art or Science-140111 - 041430

Futures Studies Art or Science-140111 - 041430

Uploaded by

faizalCopyright:

Available Formats

Is Futures Studies a Science or an Art?

By Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com). Australian Foresight Institute/Disinformation®, May 2002.

Abstract:

Futures studies is currently undergoing a process of professional legitimization. A key

debate is the status of futures research as either an art or a science. The author considers

the evolution of North American and European perspectives as a pivotal influence. Ikka

Niiniluoto’s proposal for futures as a “decision science” is contrasted with Wendell Bell’s

case for “action science” and “cultural realism.” Jerry Ravetz’s social critique of highly-

politicized science and Richard Slaughter’s model of critical futures are both mentioned

as ways to frame the sociopolitical landscape of this debate. Niiniluoto’s definition limits

the activist-emancipatory tradition and ignores contributions from hermeneutic ands

cultural theory. Resolving the art-science schism may lie in expanding the global scope of

futures and appreciating its trans-civilization knowledge base.

Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com) Page 1

Copyright 2002 Alex Burns. For individual private educational & non-commercial use only. All

other rights reserved.

Introduction: Futures Studies and Professional Legitimization

After the utopian excesses of the late 1970s, futures studies in the early 21st century is

undergoing a process of academic and professional legitimization. Debate about the

status of futures discourse, usually framed as an art-science schism, remains an important

conflict where different cultural meanings are negotiated. (Slaughter, 1999: 232-233).

Attempts to build consensus have largely occurred through membership in the major

professional institutes (the World Futures Society, the World Futures Study Federation,

the Futuribles group and the Global Business Network), by discussion in journals and

university courses, and by adherence to specific methods and tools. The art-science

schism can serve as a useful lens to view the development of futures studies and the

multi-layered approach (or not) of individual theorists and groups. Wendell Bell was

optimistic when he observed that “Everyone involved in the futurist enterprise—and, for

that matter, nonfuturist consumers of futures work—has a stake in the discussion.” (Bell,

1997: 168).

North American and European Traditions

The debate about futures as an art or science highlights the different views held by North

American and European practitioners. Influenced by Hermann Kahn and Edward

Cornish, the North American trajectory “. . . reflects a sense of optimism and power

which is, perhaps, central to the American experience.” (Slaughter, 1988: 7). Kahn and

Cornish’s emphasis on quantitative methodologies and technocratic scenarios thrived in

the post-World War II climate of ‘big science’, argues Jerry Ravetz, an era exemplified

by the 1960s Space Race and fears of thermonuclear Mutually Assured Destruction

(Ravetz, 2002: 201). The ‘forward view’ was co-opted in America by portfolio-driven

conglomerates during a frenzied period of vertical integration, and by state institutions

for budgetary planning and to inaugurate the utopian ideals of Lyndon Johnson’s Great

Society. The contrasting European tradition, exemplified by Robert Jungk and Eleonora

Masini’s visioning workshops, Bernard de Jouvenal’s The Art of Conjecture (1967), and

Johann Galtung’s peace studies, developed an activist-emancipatory tradition (Slaughter,

1988: 19) which resonated with the trans-Atlantic counterculture and antiwar movements.

This bifurcation reflected the historical matrix of differing post-World War II

experiences: the Holocaust’s ravages and Marshall Plan nation-rebuilding (Europe)

versus laissez-faire economic prosperity (North America).

American technocratic mind-sets were soon challenged by blowback from geopolitical

crises, including the Vietnam conflict and the 1973 OPEC oil crisis. Management by

Objectives gave way to scenario-driven planning and computer simulations. ‘Big science’

was simultaneously facing a post-positivist revolt, which began trickling with Thomas

Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), (Bell, 1997: 198), grew with Paul

Feyrabend’s Against Method (1975) and became a flood of postmodernist critiques. This

philosophical battle would be repeated, during the following decades, in the controversies

Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com) Page 2

Copyright 2002 Alex Burns. For individual private educational & non-commercial use only. All

other rights reserved.

regarding the epistemological status of sociobiology, memetics and evolutionary

psychology.

While these debates created the social space for futures as a “transdisciplinary social

science” (Bell, 1997: 186-187), they also undermined the epistemological assumptions of

the American tradition. The 1990s popularity of complexity theory and Eastern

pantheism heralded the demise of Cartesian dualism: “. . . the Western/industrial

worldview based on certainty, predictability, control and instrumental rationality has

become fractured and incoherent.” (Slaughter, 1988: 102).

Art and Science: A Cognitive Split

The Enlightenment’s cognitive split of art and science, for Wendell Bell, is the historical

nexus of the current debate. “The problem,” Bell observes, “is that the distinctions are

false.” (Bell, 1997: 168). Western intellectual history evolved through the counterpoint of

scientific rationality with Romanticist inspiration, organic nature by non-natural intellect.

Yet when faced with the global problematique, many futurists felt that this progression

had led to a scientific-industrial cul-de-sac (Slaughter, 1988: 101). This realization fueled

a revisionist climate that enabled Michel Foucault’s view that Western science was just

another meta-narrative to flourish. Finally, the American emphasis on quantitative

methodologies, risk management and utilitarian application by think-tanks had

contributed to an over-simplistic public image of how scientific research was actually

being conducted. “It should be remembered,” Ikka Niiniluoto notes, “that creative

imagination is needed in the discovery of scientific theories as well.” (Niiniluoto, 2001:

373).

This over-simplistic image of science has contributed to several narrow definitions of the

telos of futures studies. Jerry Ravetz warns that this image was “constructed for the needs

of particular ideological struggles” and that the sociopolitical transformation of science

was now dominated by “total commodification” (Ravetz, 2002: 201). This reductionist

logic is evident in the commercialization of the Human Genome Project, the late 1990s

dotcom consultancies, and the labyrinth patent wars being fought in biotech and

nanotechnology. Critique of individual tools needs to be extended to the sociopolitical

imperatives of futures institutes: “. . . many of the major institutional centres of futures

activity have tended to maintain close links with the centres of social and economic

power.” (Slaughter, 1988: 18).

Is Futures Studies a Decision Science?

Ikka Niiniluoto’s argument for futures studies as a “decision science” is plausible for

proponents of “total modification”. Herbert Simon’s “design science”—the systematic

deployment of optimal means for utilitarian endsis contrasted with activist views that

emphasized sociopolitical engagement and philosophical views that cultivated self-

reflexive awareness (Niiniluoto, 2001: 373). Acceptance of humanistic values, Niiniluoto

fears, may endanger the normative status of scientific discourse (Niiniluoto, 2001: 374).

The multi-motivational strategies of futures practitioners”a mixture of theoretical and

Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com) Page 3

Copyright 2002 Alex Burns. For individual private educational & non-commercial use only. All

other rights reserved.

empirical research, methodology, philosophy, and political action”results from the

creative tension of probable versus preferable futures (Niiniluoto, 2001: 376).

Niinuluoto shares Ravetz’s concerns that elites may use futures research to manufacture

the “consent of the governed” (Ravetz, 2002: 202) and prevent people from making “their

own morally and politically relevant choices.” (Niiniluoto, 2001: 373). While Ravetz,

alongside Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens, frames this confrontation as a renegotiated

“postwar social contract” (Ravetz, 2002: 201), Niinuluoto is more concerned with ethical

implications for the futurist’s employer (Niinuluoto, 2001: 374). Richard Slaughter

observes that “All science, all futures work is committed,” (Slaughter, 1988: 17), yet by

focusing on different layers, Niinuluoto and Ravetz show that the nature of this

commitment and to who it is given remains varied.

Ars, Scienta and Techne

The “decision science” frame cuts through these often-conflicting strategies: “futures

studies would not be a knowledge-seeking activity but rather a form of social technology,

comparable to the more restricted field of urban planning.” (Niiniluoto, 2001: 375). Yet

this definition remains problematic. Niiniluoto distinguishes “between scienta (as a form

of knowledge) and ars (as a form of skill.” He interprets ars as a subset of techne

(Niiniluoto, 2001: 371). Wendell Bell resolves this false dichotomy with a more precise

definition of ars “dealing with aesthetics, embracing sculpture, painting, music, poetry,

drama, dance, and even literature and some aspects of architecture.” (Bell, 1997: 169).

Niiniluoto’s focus on “futures studies as a branching tree with alternative possibilities”

and “graphical, statistical, and quantitative methods” (Niiniluoto, 2001: 373) limits his

discussion to the level of problem-oriented futures, in contrast to Ravetz’s critical mode.

Futures Discourse as Cultural Evolution

Niiniluoto recognizes that futures discourse is a form of directed cultural evolution: “an

artifact that is created by human actions.” (Niiniluoto, 2001: 375). His arguments

highlight, ironically, how transmitted ideas evolve through mutation. He prefers “the

patterns of the emergence of new scientific specialties” (Niiniluoto, 2001: 371) yet offers

few in-depth analyses of how new sciences emerge through memetic replication, group

selection and paradigm shifts. This is how scientific principles that are discovered,

refined and actualized. His focus on defining futures as “a new form of planning”

(Niiniluoto, 2001: 375) and replacing the term “descriptive science” with “decision

science” (Niiniluoto, 2001: 372-373) has already framed the terms of his ‘debate’. Ravetz

counters with “highly politicised” examples (Ravetz, 2002: 202) from the “pop-

Darwinian disciplines” and the “Gaia hypothesis” as a form of “the ecological way of

thinking.” (Ravetz, 2002: 200).

Adopting Simon’s definition consigns the spectrum of critical/epistemological futures to

the dustbin of history. It enables Niiniluoto to bypass contributions from hermeneutics

and critical theory that might have prompted him to “reflect critically upon the more-or-

less arbitrary conditions” and “skewed power relations” of applied futures (Slaughter,

Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com) Page 4

Copyright 2002 Alex Burns. For individual private educational & non-commercial use only. All

other rights reserved.

1988: 20). By adopting Simon’s definition of “decision science”, Niiniluoto offers a

prescription of things “ought to be” while deleting who decides this criteria. An ongoing

engagement with hermeneutics and critical theory reveals that the pursuit of scientific

objectivity cannot be separated from its sociopolitical origins or the wider context

(normative culture, language and tradition) that are embedded within applied research

and individual projects (Slaughter, 1988: 16). Ravetz wittily sums this up as a shift from

“the traditional grail of Truth” to “the criterion of Quality.” (Ravetz, 2002: 203).

Ikka Niiniluoto’s Cognitive Biases

Niiniluoto’s cognitive bias is also glaringly evident when he misrepresents Plato’s

definition of knowledge as meaning “the same as justified true belief” (Niiniluoto, 2001:

372). Plato actually distinguished between pistis and eikasia (preconventional emotion

and instinct), dianoia (conventional intellect) and noesis (postconventional insight). Thus

Niiniluoto also avoids Slaughter’s discussion of the foresight principle and the prospects

for developing a wisdom culture. His disavowal is a reaction to earlier attempts to codify

futures research as scientific laws (Niiniluoto, 2001: 372).

Given his private support for humanist values such as Ossip Flechtheim’s emancipatory

function (Niiniluoto, 2001: 374), Niiniluoto’s dismissal of the activist-emancipatory

tradition remains unconvincing. The original research emphasis of “decision science” has

been relegated to the “impoverished margins” of academe (Ravetz, 2002: 202). Debate

within the antiglobalist and environmental movements has also shown that laypersons

can challenge experts, contribute to forming policies and deconstructing hidden

ideologies (Ravetz, 2002: 202). Ravetz defines the scientific battleground as being fought

“between reductionist corporate science assuming total certainty and control, and

wholistic environmental/critical science concerned with uncertainty and irreparable

harm.” (Ravetz, 2002: 202-203). Critiques of “decision science”, consequently, parallel

fears that the “professionalising” of futures will limit dissenting voices and alternate

visions.

Wendell Bell Exits the Labyrinth

Wendell Bell proposes three solutions to the art-science schism and the post-positivist

revolt. The first is a recognition that many pioneers, notably Daniel Bell and Bernard de

Jouvenal, felt “that the futures field by its very nature cannot be a science . . . Moreover,

many working futurists today, perhaps a majority, would agree that futures studies is an

art.” (Bell, 1997: 167). Yet Bell concluded that artists, unlike scientists, “are not

obligated by their commitment to art to tell the truth.” (Bell, 1997: 172). This ignores the

domain of Sacred Art (which does hold this obligation) and probably denotes the

lingering influence of post-Dada cynicism and Pop commerciality. Bell’s insight suggests

that the art-science schism is an inter-generational paradigm shift still in-progress and

that a new generation of futurists may have different orientations.

Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com) Page 5

Copyright 2002 Alex Burns. For individual private educational & non-commercial use only. All

other rights reserved.

The second solution Bell offers is to replace Niiniluoto’s “decision science” with an

“action science” orientation (Bell, 1997: 181) that enables the fusion of scientific

methods” conditionals, counterfactuals, dispositionals, theoretical speculations,

creative formulations of hypotheses, and predictions”with the awareness of

psychological, economic, cultural and sociopolitical implications of forecasts (Bell, 1997:

179, 182).

Finally, Bell navigates out of the post-positivist cul-de-sac through Critical Realism,

which defines science as “a body of linguistic or numerical statements about the nature of

reality,” (Bell, 1997: 207), acknowledges sensory knowledge, personal and social biases,

and the simultaneous evolution of discourse “by small continuous additions and

discontinuous paradigms.” (Bell, 1997: 208). Critical Realism appeals to Bell, post-

l’affaire Sokal, because it combines empirical logic, a construction of social reality, “the

conjectural aspects of knowledge, the many threats to validity, and limitations to knowing

with certitude.” (Bell, 1997: 208).

Conclusion: The Dawning of Postconventional Insight

Resolving the art-science schism involves reframing the Aristotelian ‘either-or’ question

into a non-Aristotelian formulation. Proponents of the critical futures tradition have

recognized the need for a “variety of criteria to assess knowledge.” (Slaughter, 1988: 16).

One regenerative solution to the art-science schism may lie in expanding the global scope

of futures and appreciating its trans-civilization knowledge base. To-date, futures

discourse has been molded by existential knowledge of the human condition and the past,

and by the “images, beliefs, goals, values and intentions” of its practitioners (Bell, 1997:

174-179). The current search for a ‘Theory of Everything’ and investigation of

postconventional insight will replace the art-science schism with a more inclusive

framework. The trans-disciplinary focus of futures studies may be closer to Ken Wilber’s

synthesis and Edward O. Wilson’s consilience than the separation implied by Stephen Jay

Gould’s non-overlapping magisteria.

Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com) Page 6

Copyright 2002 Alex Burns. For individual private educational & non-commercial use only. All

other rights reserved.

Select Bibliography

Bell, Wendell (1997). Foundations of Future Studies (volume one). New Brunswick, NJ:

Transaction Publishers.

Niiniluoto, Ilkka (2001). “Future Studies: Science or Art?” Futures 33: 371-377.

Ravetz, Jerry (2002). “The Challenge Beyond Orthodox Science.” Futures 34: 200–203.

Slaughter, Richard (1988). Recovering the Future. Clayton: Monash University Graduate

School of Environmental Science.

Slaughter, Richard (1999). Futures for the Third Millennium: Enabling the Forward

View. St Leonards: Prospect Media.

Alex Burns (alex@disinfo.com) Page 7

Copyright 2002 Alex Burns. For individual private educational & non-commercial use only. All

other rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5808)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (843)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Science Olympiad 2020 Cheat SheetDocument4 pagesScience Olympiad 2020 Cheat SheetLisa RetbergNo ratings yet

- Ernst Mach's World Elements - Erik BanksDocument300 pagesErnst Mach's World Elements - Erik Banksphilosoraptor92No ratings yet

- Weaknesses of Casual Models With Multiple Roles Elements: January 2014Document15 pagesWeaknesses of Casual Models With Multiple Roles Elements: January 2014weranNo ratings yet

- rzStructural_Equation_ModelingDocument21 pagesrzStructural_Equation_ModelingweranNo ratings yet

- Writing Numbers Through 1 Million: AnswersDocument2 pagesWriting Numbers Through 1 Million: AnswersweranNo ratings yet

- Research Trends in The Academy of Management PublicationsDocument31 pagesResearch Trends in The Academy of Management PublicationsweranNo ratings yet

- 26 Algebraic: Unit Expressions and EquationsDocument1 page26 Algebraic: Unit Expressions and EquationsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 26 Practice Problems: Unit 26 Answers Are On Page 239. Unit 26 Additional Practice Problems Are On PageDocument1 pageUnit 26 Practice Problems: Unit 26 Answers Are On Page 239. Unit 26 Additional Practice Problems Are On PageweranNo ratings yet

- Current Trends and Issues in RESEARCH and Its MANAGEMENT: Chiang Mai Journal of Science September 2010Document7 pagesCurrent Trends and Issues in RESEARCH and Its MANAGEMENT: Chiang Mai Journal of Science September 2010weranNo ratings yet

- Urdu Worksheet 1Document1 pageUrdu Worksheet 1weranNo ratings yet

- We Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsDocument17 pagesWe Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 27: Practice ProblemsDocument1 pageUnit 27: Practice ProblemsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 25: Practice ProblemsDocument1 pageUnit 25: Practice ProblemsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 32 Solving Formula Problems: Formula: D RT 420 Miles (R) (7 Hours)Document1 pageUnit 32 Solving Formula Problems: Formula: D RT 420 Miles (R) (7 Hours)weranNo ratings yet

- Unit 27: Solving Multi-Step EquationsDocument1 pageUnit 27: Solving Multi-Step EquationsweranNo ratings yet

- 33 Problems: PracticeDocument1 page33 Problems: PracticeweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 31 Practice: ProblemsDocument1 pageUnit 31 Practice: ProblemsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 29: Triangles and Other PolygonsDocument1 pageUnit 29: Triangles and Other PolygonsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 29: Practice ProblemsDocument1 pageUnit 29: Practice ProblemsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 28 Practice Problems: (A) An Angle With 900Document1 pageUnit 28 Practice Problems: (A) An Angle With 900weranNo ratings yet

- Unit 33 Measuring Perimeter and Circumference: 3. Pi (Pronouncedpie) Is The Numberof 3 14Document1 pageUnit 33 Measuring Perimeter and Circumference: 3. Pi (Pronouncedpie) Is The Numberof 3 14weranNo ratings yet

- Using Formulasto Solve ProblemsDocument1 pageUsing Formulasto Solve ProblemsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 37: Practice ProblemsDocument1 pageUnit 37: Practice ProblemsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 34: Measuring AreaDocument1 pageUnit 34: Measuring AreaweranNo ratings yet

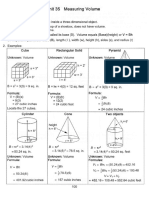

- Unit 35 PDFDocument1 pageUnit 35 PDFweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 35: Measuring VolumeDocument1 pageUnit 35: Measuring VolumeweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 34: Practice ProblemsDocument1 pageUnit 34: Practice ProblemsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 36 Business Formulas: I PRTDocument1 pageUnit 36 Business Formulas: I PRTweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 37 Other Interesting FormulasDocument1 pageUnit 37 Other Interesting FormulasweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 39: Word Problems Using Whole Numbers and DecimalsDocument1 pageUnit 39: Word Problems Using Whole Numbers and DecimalsweranNo ratings yet

- Unit 40 Practice Problems: Unit 40 Answers Are On Page 240. Unit 40 Additional Practice Problems Are On Page 194. 117Document1 pageUnit 40 Practice Problems: Unit 40 Answers Are On Page 240. Unit 40 Additional Practice Problems Are On Page 194. 117weranNo ratings yet

- Multi-Step Word Problems: Unit 38Document2 pagesMulti-Step Word Problems: Unit 38weranNo ratings yet

- BLJ Lesson1Document1 pageBLJ Lesson1JEANNo ratings yet

- Getting Started With CygwinDocument22 pagesGetting Started With CygwinJignaNo ratings yet

- Colloid Chemistry and Phase Rule 4022146-1: (Essentials of Physical Chemistry - Arun Bahl & B.S. Bahl) Chapter 19 and 22Document51 pagesColloid Chemistry and Phase Rule 4022146-1: (Essentials of Physical Chemistry - Arun Bahl & B.S. Bahl) Chapter 19 and 22Razan khalidNo ratings yet

- Ibanez-Guitars Basses AdjustDocument4 pagesIbanez-Guitars Basses AdjustRosalba Maria Leal GiffoniNo ratings yet

- Political Interference and Regulatory Role of The National Broadcasting Commission in NigeriaDocument150 pagesPolitical Interference and Regulatory Role of The National Broadcasting Commission in Nigeriachukwu solomonNo ratings yet

- Principles of LegislationDocument20 pagesPrinciples of LegislationadhiNo ratings yet

- Unit7-CNC Machining CentresDocument56 pagesUnit7-CNC Machining Centresvasudevanrv9405No ratings yet

- Guia Cambio de TransistoresDocument291 pagesGuia Cambio de TransistoresRicardo RiveraNo ratings yet

- Romantic Movies With Bangla SubtitleDocument6 pagesRomantic Movies With Bangla SubtitleTanzimul Lemon100% (1)

- Unit 2 Test: VocabularyDocument4 pagesUnit 2 Test: Vocabularyсабина батыргали100% (1)

- Lecture 2 - Water Sensitive Urban Design 2016 Full Slides PDFDocument24 pagesLecture 2 - Water Sensitive Urban Design 2016 Full Slides PDFAndyNo ratings yet

- Romania Off Plan Property Investment and OpportunitiesDocument12 pagesRomania Off Plan Property Investment and Opportunitiespropertyinvestment100% (2)

- Petition: Magbilang, o Mapabilang, Sa Mga Biktima NG Climate Change?"Document65 pagesPetition: Magbilang, o Mapabilang, Sa Mga Biktima NG Climate Change?"climatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Ecotourism 02Document18 pagesEcotourism 02RosemariePletadoNo ratings yet

- RA 8293-Intellectual Property Code of The PhilippinesDocument57 pagesRA 8293-Intellectual Property Code of The PhilippinesDha RylNo ratings yet

- 3 Asian Values Universality of HRDocument6 pages3 Asian Values Universality of HRElixirLanganlanganNo ratings yet

- Question Bank On Central Banks MCQsDocument20 pagesQuestion Bank On Central Banks MCQsabhilash k.b78% (9)

- (Ronald R - Lee, J - Colby Martin) Psychotherapy After KohutDocument353 pages(Ronald R - Lee, J - Colby Martin) Psychotherapy After KohutFrancisco Robles100% (1)

- Lesson 7 WIKADocument24 pagesLesson 7 WIKANina Alliah J BayangatNo ratings yet

- Simple Python HTTP (S) Server - Example AnvilEight BlogDocument7 pagesSimple Python HTTP (S) Server - Example AnvilEight Blogmamad babaNo ratings yet

- Template AMEFDocument10 pagesTemplate AMEFElvis DiazNo ratings yet

- Tallon Nielsen Final Paper Bio 1615Document4 pagesTallon Nielsen Final Paper Bio 1615api-242199679No ratings yet

- Keterampilan Report TextDocument10 pagesKeterampilan Report TextRahiel Abrar 8.3No ratings yet

- Early Middle College FaqsDocument14 pagesEarly Middle College FaqsWDIV/ClickOnDetroitNo ratings yet

- MOTION FOR EXECUTION-PesimoDocument4 pagesMOTION FOR EXECUTION-PesimoLeo Archival ImperialNo ratings yet

- Laporan Arus Kas Ukk 2022Document2 pagesLaporan Arus Kas Ukk 2022dwi750No ratings yet

- DK Children My Encyclopedia of Very Important AdventuresDocument226 pagesDK Children My Encyclopedia of Very Important AdventuresVinhhoa Pham100% (8)

- XiiDocument2 pagesXiiselinafibri1No ratings yet