Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Working Paper WP-1156-E November, 2016: Inflation

Uploaded by

Bright MafungaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Working Paper WP-1156-E November, 2016: Inflation

Uploaded by

Bright MafungaCopyright:

Available Formats

Working Paper

WP-1156-E

November, 2016

INFLATION

Antonio Argandoña

IESE Business School – University of Navarra

Av. Pearson, 21 – 08034 Barcelona, Spain. Phone: (+34) 93 253 42 00 Fax: (+34) 93 253 43 43

Camino del Cerro del Águila, 3 (Ctra. de Castilla, km 5,180) – 28023 Madrid, Spain. Phone: (+34) 91 357 08 09 Fax: (+34) 91 357 29 13

Copyright © 2016 IESE Business School. IESE Business School-University of Navarra - 1

INFLATION

Antonio Argandoña1

Abstract

This is an entry for the second edition of Sage's Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society. It

is a brief explanation of inflation, its causes and its consequences. Inflation has important

economic, political, social and ethical implications for countries, especially because it affects the

standard of living and distribution of income among citizens. The entry also discusses how

inflation can be reduced and touches upon the issue of deflation.

Keywords: Inflation; Prices; Income distribution; Monetary policy; Ethics

1

"La Caixa" Chair of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Governance

IESE Business School-University of Navarra

INFLATION

Introduction

Inflation is a continued and sustained rise in the general price level of a country, or, equivalently,

a continuous decrease in the value of money. Specifically, inflation is not an increase in a few

prices but in a large number of prices at once; not a one-time increase but an increase that

spreads out over time; and not a temporary, reversible phenomenon, such as the seasonal increase

in the prices of certain consumer goods, but a sustained increase. Usually, inflation is measured

by the change in some price index, based on a basket of goods and services, such as the consumer

price index (CPI). Inflation has important economic, political, social and ethical implications for

countries, especially because it affects the standard of living and distribution of income among

their citizens.

IESE Business School-University of Navarra

What Causes Inflation?

Many factors may cause the price of a good to increase on a one-time basis. These include an

increase in demand for the product, a reduction in supply (a bad harvest, for example), an increase

in costs (wages, materials, energy), and a rise in taxes. Nevertheless, these events may explain

one-time price increases but not continued and sustained increases in the prices of large numbers

of goods over an extended period, which is the definition of inflation.

There is a broad consensus among economists that inflation can be caused only by a high rate

of growth of the quantity of money in a country over a long period. That is why inflation is

called a monetary phenomenon, expressed as too much money chasing too few goods. According

to this explanation, if a country’s financial system creates more money than the value of the

goods available, a bidding war ensues among potential buyers, which leads to price increases.

These price increases pass from one market to another and can persist over time if the quantity

of money increases. Therefore, in order to explain inflation, we need to understand how money

is created and, given that monetary policy is responsible for the control of the quantity of money,

we should ask ourselves what role should be attributed to the monetary authorities in the creation

of inflation.

However, if it is public knowledge that the excessive growth of the quantity of money leads to

inflation, why do governments promote it or allow it to happen? There are many reasons why

they might do this. For example, they may be trying to stimulate demand and production, to

avoid recession, or to address mistakes or accidents. Historically, the most frequent cause of

excessive growth in the money supply has been the financing of the budget deficit. Specifically,

when a government spends above its means, it is tempted to ask the central bank for a loan, and

that loan gives rise to an increase in the quantity of money in the economy. In many countries,

the ultimate cause of chronic high inflation has been the government’s inability to finance public

spending out of its regular revenues, prompting it to resort to inflationary means of financing.

For this reason, many countries have passed statutes that guarantee the independence of the

central bank with respect to the government.

Consequently, wherever inflation is high and persistent, it tends not to be an isolated disorder

but part of a broader problem in the context of expansionary fiscal policies, populist

governments, and central banks held hostage to political pressure or a lack of appropriate

monetary policy tools. In the long run, the price increases may become self-perpetuating because,

when money is losing value, consumers try to spend it as quickly as possible. Consequently,

prices increase to the point where hyperinflation may occur, which means that prices could rise

at an annual rate of more than 1,000%. Two extreme examples of hyperinflation are Germany

after World War I, where the growth rate of prices reached 3.25 million percent in August 1923,

and Zimbabwe, where prices grew at an annual rate of 489 billion percent in September 2008.

Although inflation is typically linked to expansionary monetary policy, its deeper causes may be

social, political or economical. Often monetary authorities try to accelerate the growth of

production and employment in the short term to avoid the recessionary effects of a rise in wages

or oil prices or to facilitate a redistribution of income, forgetting that this can lead to higher,

more durable inflation in the long term.

2 - IESE Business School-University of Navarra

Economic and Social Effects of Inflation

Inflation poses economic and social problems, mainly because it has negative consequences for

the operation of an economy and the welfare of its citizens. In economic terms, a country with

high inflation and a fixed exchange rate will become less competitive, and this may result in low

growth and high unemployment. Moreover, the currency of a country experiencing inflation may

be subject to speculative attacks that cause sudden devaluations that accelerate inflation and

disrupt production. The severe adjustment costs that follow will probably lead to a recession.

An economy with high and variable inflation is likely to be less efficient because the market

signals are distorted. For example, companies may find it difficult to determine whether the

higher price of a specific good is due to higher demand for this good or to a general rise in many

prices, and this confusion may lead to erroneous decisions regarding production and investment.

Moreover, price volatility can create uncertainty in the financial markets, and this may shorten

the maturity of credit, hindering the financing of long-term investments.

Inflation is also a tax on money, as is evident when considering that the loss in purchasing power

of a dollar bill kept for one year with an inflation rate of 10% is equivalent to paying a 10%

annual tax on that dollar bill. This result may be considered unfair and undemocratic. Moreover,

when inflation is high, the ability to speculate in the financial markets becomes more profitable

than work itself.

As the welfare of many citizens is threatened, they may feel wronged. Distributive justice or the

fairness of income distribution is at stake. Specifically, high inflation brings about a redistribution

of income that particularly harms those on a fixed income, such as public pensions or rents. It

also harms those who hold cash or fixed-income securities, as well as creditors, given that the

value of payments declines under conditions of inflation. After an episode of high inflation,

savers may find that their wealth has evaporated, unless it was invested in securities whose value

kept pace with inflation. Additionally, inflation accentuates the income tax progression by

pushing the base up into higher tax brackets, without any corresponding increase in real income.

In society at large, high and variable inflation may generate ill-feeling and conflict, because

citizens will see how prices increase day by day while their wages increase only once a year.

Whenever inflation is high, people tend to pin the blame on minorities, intermediaries or

speculators, which can fuel social violence. Moreover, in an environment of high inflation, ethical

and social values – such as honesty, industry and saving – may deteriorate. For example, people

may believe that it does not pay to be honest because they end up forfeiting their assets while

those who resort to financial speculation may make significant gains.

Also, inflation tends to spread. A rise in one price leads to a rise in another and, more generally,

prices can push up wages and wages can push up prices in a chain of defensive reactions. The

effects of inflation are most severe when its rate is unpredictable and when citizens are unable

to protect their wealth from price swings. Inflation harms citizens’ trust in the economic system

since it affects their purchasing power. On the other hand, low, stable and predictable inflation

allows the development of defense mechanisms, such as wage gains obtained through collective

bargaining that maintains purchasing power.

IESE Business School-University of Navarra - 3

How Can Inflation Be Reduced?

If inflation is a monetary phenomenon, reducing a country’s inflation rate is the main task of the

central bank, which should curb the growth of the money supply and credit by raising interest

rates and draining liquidity from the financial system. However, this can be a traumatic process

because many households will find themselves in financial difficulties and will curtail their

demand. Subsequently, many companies will experience low profits, halt their investments, cut

back their spending and lay off workers. Because this is a recipe for recession, many countries

that have tried to reduce inflation have found that implementing a restrictive monetary policy is

not enough. This policy must also be credible, which is to say that the authorities must have a

firm political will to reduce inflation and to bear the economic and social costs of preventing

prices from rising.

Furthermore, an anti-inflationary monetary policy will be credible only if it is compatible with

other policies, above all exchange rate policy and fiscal policy – that is, the government should

control its deficit. Lastly, the battle against inflation will be easier if institutions and policies are

in place to facilitate price adjustment (for example, labor market flexibility and open and

competitive markets for goods and services) and if they do not resort to so-called incomes policy

because, while the freezing of prices and wages may seem to be a useful instrument to avoid the

evils of inflation, its consequences are disastrous, especially for low-income citizens, because of

the shortages of the goods whose prices were controlled.

Once the inflation rate has been brought down, monetary policy will have to be aimed at keeping

it low. This means that the rate of growth of the money supply must be sufficient to finance the

growth of the economy in real terms, plus a low inflation rate. Once again, that will require a

credible deficit-containing fiscal policy, a sustainable exchange rate and a fair dose of good luck.

All of this brings us back to the attitude that a socially responsible government should take

toward inflation. The most important thing is not to allow unduly expansionary policies, which

generate inflation. Excessive money supply growth has a stimulating effect on the real economy

in the short term, just as alcohol does on a person, but the effect soon wears off, the negative

consequences persist and the dose needed to achieve the same effect keeps on increasing.

Inflation is a problem for many countries but has not always been so in the past. During the

recent financial crisis it has ceased to be an issue in some countries because what has occurred

is negative inflation or deflation. This shows the ambiguity of these phenomena: inflation disturbs

the efficiency of the economic system but deflation also causes evils. For example, it increases

the debt burden of households and companies because debt must be returned in units of a

currency whose purchasing power has increased. Real interest rates may be high and there may

be barriers to lowering them, while the expectation of falling prices can lead households to delay

their consumption decisions to take advantage of lower prices, resulting in reduced demand and

an aggravated recession. Prudence calls for moving the economy between the rock of inflation

and the hard place of deflation.

– Antonio Argandoña

4 - IESE Business School-University of Navarra

See also Income distribution; Justice, distributive; Monetary policy; Regressive tax; Seigniorage;

Wage and price controls.

Further Reading and References

Bagus, P., Howen, D. & Gabriel, A. (2014). “Causes and Consequences of Inflation.” Business and

Society Review, 119(4), 497–517.

Parkin, M. (1987). “Inflation.” In J. Eatwell, M. Milgate & P. Newman (eds.). The New Palgrave: A

Dictionary of Economics (vol. 2). London: Macmillan.

Parkin, M. (ed.) (1994). The Theory of Inflation. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Romer, C.D. & Romer, D.H. (eds.) (1997). Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Siklos, P.L. (ed.) (1995). Great Inflations of the 20th Century: Theories, Policies and Evidence.

Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

IESE Business School-University of Navarra - 5

You might also like

- Introduction of InflationDocument45 pagesIntroduction of InflationSandeep ShahNo ratings yet

- Inflation in Pakistan Economics ReportDocument15 pagesInflation in Pakistan Economics ReportQanitaZakir75% (16)

- Ihna 10Document3 pagesIhna 10Robert GarlandNo ratings yet

- Grain and FeedDocument14 pagesGrain and FeedsaadNo ratings yet

- Esp Gawa at Kilos LoobDocument1 pageEsp Gawa at Kilos LoobLance RV JoteaNo ratings yet

- Inflation Rate ThesisDocument6 pagesInflation Rate ThesisBuyCheapPapersMiramar100% (2)

- InflationDocument2 pagesInflationhamza.shaheenNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Macroeconomics Project: Anti-Unemployment and Anti-Inflation Polices in RomaniaDocument28 pagesQuantitative Macroeconomics Project: Anti-Unemployment and Anti-Inflation Polices in RomaniaAndreea OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Inflation FileDocument5 pagesInflation FileDaliopac John PaulNo ratings yet

- Inflation FileDocument5 pagesInflation FileDaliopac John PaulNo ratings yet

- Inflation FileDocument5 pagesInflation FileDaliopac John PaulNo ratings yet

- Inflation FileDocument5 pagesInflation FileDaliopac John PaulNo ratings yet

- Currency: Inflation Is A Key Concept in Macroeconomics, and A Major Concern For Government PolicymakersDocument3 pagesCurrency: Inflation Is A Key Concept in Macroeconomics, and A Major Concern For Government PolicymakersElvie Abulencia-BagsicNo ratings yet

- Inflation and Its ControlDocument20 pagesInflation and Its Controly2j_incubusNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Impact of Inflation On Economic GrowthDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Impact of Inflation On Economic Growthc5g10bt2No ratings yet

- INFLATIONDocument2 pagesINFLATIONMaricar DomalligNo ratings yet

- Seminar in Economic Policies: Assignment # 1Document5 pagesSeminar in Economic Policies: Assignment # 1Muhammad Tariq Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Inflation, Types and Pakistan's Inflation: Mam Fadia NazDocument16 pagesInflation, Types and Pakistan's Inflation: Mam Fadia NazGhulamMuhammad ChNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Report On Inflation and UnemploymentDocument15 pagesMacroeconomics Report On Inflation and UnemploymentAmar Nam JoyNo ratings yet

- Conflicting Goals in Economic Growth PDFDocument2 pagesConflicting Goals in Economic Growth PDFMrunaal NaseryNo ratings yet

- Inflation in PakistanDocument35 pagesInflation in Pakistanhusna1100% (1)

- Inflation 1Document18 pagesInflation 1Dương Thị Kim HiềnNo ratings yet

- The Looming Shadow of InflationDocument1 pageThe Looming Shadow of InflationElla Mae VergaraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Proposal PDFDocument13 pagesThesis Proposal PDFHimale AhammedNo ratings yet

- What Is Inflation-FinalDocument2 pagesWhat Is Inflation-FinalArif Mahmud MuktaNo ratings yet

- Expert Explains - What Are The Real Causes of InflationDocument6 pagesExpert Explains - What Are The Real Causes of InflationUdbhavNo ratings yet

- Economy Part 5Document13 pagesEconomy Part 5Shilpi PriyaNo ratings yet

- InflationDocument9 pagesInflationUniversal MusicNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Economic Environment Business InflationDocument52 pagesExecutive Summary: Economic Environment Business Inflationsj_mukherjee5506No ratings yet

- SS408 - Prefinal ModulesDocument11 pagesSS408 - Prefinal ModulesAnna Liza MojanaNo ratings yet

- INFLATIONDocument17 pagesINFLATIONlillygujjarNo ratings yet

- What Is InflationDocument7 pagesWhat Is InflationCynthiaNo ratings yet

- Inflation Essay Q6Document4 pagesInflation Essay Q6Vladimir KaretnikovNo ratings yet

- Sanchith Economics SynopsisDocument16 pagesSanchith Economics SynopsisShaurya PonnadaNo ratings yet

- Spotnomics JanDocument2 pagesSpotnomics JanSaira KousarNo ratings yet

- Global InflationDocument16 pagesGlobal InflationImeth Santhuka RupathungaNo ratings yet

- Inflation Impact On EconmyDocument4 pagesInflation Impact On EconmyRashid HussainNo ratings yet

- EconDocument19 pagesEconkajan thevNo ratings yet

- Explain The Functions of Price in A Market EconomyDocument6 pagesExplain The Functions of Price in A Market Economyhthomas_100% (5)

- Guide To UK Inflationary PressuresDocument21 pagesGuide To UK Inflationary PressuresMalik SaadoonNo ratings yet

- Wat Is InflationDocument2 pagesWat Is Inflationindukj1988No ratings yet

- Assignment of InflationDocument13 pagesAssignment of InflationSaira KousarNo ratings yet

- Inflation-Conscious Investments: Avoid the most common investment pitfallsFrom EverandInflation-Conscious Investments: Avoid the most common investment pitfallsNo ratings yet

- Macro - FInal (2nd Y, 2nd Sem)Document28 pagesMacro - FInal (2nd Y, 2nd Sem)MdMasudRanaNo ratings yet

- InflationDocument15 pagesInflationUsaf SalimNo ratings yet

- Monetary Economics AssignmentDocument6 pagesMonetary Economics AssignmentNokutenda Kelvin ChikonzoNo ratings yet

- Inflation in BangladeshDocument19 pagesInflation in Bangladeshradia3990100% (1)

- What Is "ECONOMY"?: Impact of Inflation On Indian EconomyDocument20 pagesWhat Is "ECONOMY"?: Impact of Inflation On Indian EconomyAbhilash ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Chapter One For Ijeoma IG CLASS-1Document77 pagesChapter One For Ijeoma IG CLASS-1Onyebuchi ChiawaNo ratings yet

- Guide To Economics: Part ofDocument11 pagesGuide To Economics: Part ofLJ AbancoNo ratings yet

- Causes of InflationDocument23 pagesCauses of InflationShravan VanaparthiNo ratings yet

- Impact of Relative Price Changes and Asymmetric Adjustments On Aggregate InflationDocument4 pagesImpact of Relative Price Changes and Asymmetric Adjustments On Aggregate InflationEizen LuisNo ratings yet

- Global Capital Markets and Investment BankingDocument6 pagesGlobal Capital Markets and Investment BankingKARANUPDESH SINGH 20212627No ratings yet

- Causes of InflationDocument15 pagesCauses of Inflationkhalia mowattNo ratings yet

- Preserving Wealth in Inflationary Times - Strategies for Protecting Your Financial Future: Alex on Finance, #4From EverandPreserving Wealth in Inflationary Times - Strategies for Protecting Your Financial Future: Alex on Finance, #4No ratings yet

- 4 HUSAIN Anti-Inflation PolicyDocument9 pages4 HUSAIN Anti-Inflation PolicyKeran VarmaNo ratings yet

- Inflation Tutorial: (Page 1 of 7)Document7 pagesInflation Tutorial: (Page 1 of 7)Deepesh VaishanavaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Inflation in Our CountryDocument16 pagesEffects of Inflation in Our CountrySohaib JavedNo ratings yet

- Inflation V/S Interest Rates: Grou P6Document26 pagesInflation V/S Interest Rates: Grou P6Karan RegeNo ratings yet

- Bes Cala 4Document1 pageBes Cala 4Bright MafungaNo ratings yet

- 14.30-16.00 2 BoltDocument51 pages14.30-16.00 2 BoltBright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Inov A 00071Document25 pagesInov A 00071Bright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Background Doc2 For Paper 39 (ILO-WP-90)Document83 pagesBackground Doc2 For Paper 39 (ILO-WP-90)Bright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Evaluation of Unbranded and Unlabelled Food Products: The Case of BacalhauDocument17 pagesConsumer Evaluation of Unbranded and Unlabelled Food Products: The Case of BacalhauBright MafungaNo ratings yet

- 188343-Article Text-478475-1-10-20190722Document24 pages188343-Article Text-478475-1-10-20190722Bright MafungaNo ratings yet

- 2022heritage Cala 3CDocument5 pages2022heritage Cala 3CBright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Bes Cala 5 Pres GD EducationDocument2 pagesBes Cala 5 Pres GD EducationBright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Responding To COVID-19:: Highlights of A Survey in ZIMBABWEDocument6 pagesResponding To COVID-19:: Highlights of A Survey in ZIMBABWEBright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Cala - History 1 (1) 2Document2 pagesCala - History 1 (1) 2Bright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Cala Com Scie 5Document4 pagesCala Com Scie 5Bright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Bes Cala 4Document4 pagesBes Cala 4Bright MafungaNo ratings yet

- Midterm 2 With AnswersDocument5 pagesMidterm 2 With AnswersJijisNo ratings yet

- ch.15 TB 331Document10 pagesch.15 TB 331nickvandervNo ratings yet

- 2nd Dessert at Ion Draft-1Document27 pages2nd Dessert at Ion Draft-1Peter WoodsNo ratings yet

- MULTIPLE CHOICE. Choose The One Alternative That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionDocument14 pagesMULTIPLE CHOICE. Choose The One Alternative That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionOsvaldo GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- 1 Euro To Usd - Google SearchDocument1 page1 Euro To Usd - Google Searchfake nameNo ratings yet

- Horizontalists Vs Verticalists 25 Years LaterDocument15 pagesHorizontalists Vs Verticalists 25 Years Laterpaul_aNo ratings yet

- Johnny FinalDocument4 pagesJohnny FinalNikita SharmaNo ratings yet

- 79 196 1 SM PDFDocument15 pages79 196 1 SM PDFaryarahardyaNo ratings yet

- Defining and Analyzing The International Monetary SystemDocument28 pagesDefining and Analyzing The International Monetary SystemNur Amaliatus FaudinaNo ratings yet

- QuestionnaireDocument6 pagesQuestionnaireKenshin SophisticNo ratings yet

- Putting All Markets Together: The AS-AD ModelDocument22 pagesPutting All Markets Together: The AS-AD ModelMohammadTabbal100% (1)

- Central BankDocument17 pagesCentral BankGaurav KumarNo ratings yet

- What Is Monetary PolicyDocument12 pagesWhat Is Monetary PolicyNain TechnicalNo ratings yet

- Velocity of MoneyDocument1 pageVelocity of MoneyGood Myrmidon100% (1)

- Contemporary WorldDocument4 pagesContemporary WorldTheodore GallegoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 - Managing Nondeposit LiabilitiesDocument16 pagesChapter 13 - Managing Nondeposit LiabilitiesAhmed El KhateebNo ratings yet

- CH 06 - Macro Part 3Document18 pagesCH 06 - Macro Part 3Samar GrewalNo ratings yet

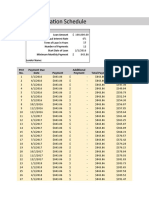

- Loan Amortization ScheduleDocument10 pagesLoan Amortization ScheduleCrisant DemaalaNo ratings yet

- MoneyDocument18 pagesMoneySURAJ GADAVENo ratings yet

- Worksheet (Chapter 15) Foreign Exchange Rate Market (Part1) : SolveDocument2 pagesWorksheet (Chapter 15) Foreign Exchange Rate Market (Part1) : SolveAhmed DabourNo ratings yet

- Loan Amortization Schedule TemplateDocument12 pagesLoan Amortization Schedule TemplateIfeOluwaNo ratings yet

- Bank LoansDocument20 pagesBank LoansMihir ShahNo ratings yet

- FIN 4 Data File - Loan Amortization TableDocument5 pagesFIN 4 Data File - Loan Amortization TableAndyTomasNo ratings yet

- Relationships Between Inflation, Interest Rates, and Exchange RatesDocument18 pagesRelationships Between Inflation, Interest Rates, and Exchange Ratesjahirul munnaNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Cost of Living: Solutions To Text ProblemsDocument4 pagesMeasuring The Cost of Living: Solutions To Text ProblemsMARTIAL9No ratings yet

- Is LM PDFDocument9 pagesIs LM PDFShivam SoniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Money and InflationDocument37 pagesChapter 4: Money and InflationMinh HangNo ratings yet

- Inflation DeflationDocument76 pagesInflation DeflationDeepakHeikrujam0% (1)

- Lesson 5 - Mortgage UpdatedDocument46 pagesLesson 5 - Mortgage Updatedrara wongNo ratings yet

- Currency Market Weekly ReportDocument5 pagesCurrency Market Weekly ReportRahul SolankiNo ratings yet