Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Blithe Dale Term

Uploaded by

kevinandy83Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Blithe Dale Term

Uploaded by

kevinandy83Copyright:

Available Formats

Kevin Cline The Sexuality Frustrated Narrator: A Contemporary Look at Coverdales Interpretations of Women and Men in Hawthornes The

Blithedale Romance. October 24, 2005 English 422: Dr. Rodier

I never had a nightcap in my life! Coverdale, pg 51. A nightcap is another word for sex (thinly veiled enthusiasm for). Would you like to come upstairs for a nightcap? http://www.urbandictionary.com. Contemporary readers of Nathaniel Hawthornes The Blithedale Romance first meet the narrator walking to his bachelor-apartment after attending the wonderful exhibition of the Veiled Lady (Hawthorne 5). From the first page, the contemporary reader may decide whether he will assume that the narrator was merely attending a play, a vocal concert, or something mainstream, or if this self-professed bachelor attended a more vulgar exhibition that evening. Though the former may be more widely accepted, one cannot discount the latter interpretation in a modern society where a popular psychological study found that men think of sex every seven seconds. With sex on the minds of some prospected readers (males), it is not erroneous to interpret the lines as the pathetic confession of a sexually frustrated man telling his readers he lives alone watches women in show. Throughout The Blithedale Romance, the narrator, named Coverdale, proves to the contemporary reader that he was sexually frustrated through his interactions with and interpretations of Zenobia, Hollingsworth, and Priscilla. Coverdale presents the characters he plays with in the novel from the start. On page 13, Coverdale explains to the reader the name of Zenobia by saying that it was not her real name, and that she assumed it, and her friends adopted it in familiar intercourse with her. The word intercourse in that passage is full of sexual meaning to many contemporary readers. Though implying that a contemporary reader would not understand other practical uses of the word besides that of the sex would be unfair, it is the familiar use in the modern society. Therefore, with this inclination toward sex, the reader then looks to see how Coverdale himself ranks in Zenobias world with words like, our Zenobia on page 13. Perhaps he is alluding to being a friend of Zenobia, but Coverdale never says we when describing Zenobias friends. On page

14, Coverdale quotes Zenobia saying, I have long wished to know you, Mr. Coverdale . . . This implies that Coverdale also wished to know Zenobia in perhaps the same familiar way that her friends knew her. Coverdales sexual impulses for Zenobia do not end with her name, as on page 15 Coverdale shows the reader that Zenobia wears a flower in her hair, which can be symbolic and mean that he has yet to deflower Zenobia. This analogy of flowers and sex not only has root in the modern world, but also on page 72 of the novel where Coverdale is describing Priscilla (another character to be addressed later). Coverdale says, Priscilla had grown to be a very pretty girl, and still kept budding and blossoming. If flowering terminology can be used to describe the physical maturity of Priscilla, it is certainly conceivable that Coverdale meant the flower in Zenobias hair to have some sexual connotations to it as well. Again, Coverdale is showing the reader what he desires, what he does not see fulfilled. Continuing with the sexual allusions to Zenobia and Coverdales inability to see them through, Coverdale almost admits that he will never get the chance to deflower Zenobia on page 164. Here, Coverdale shows the reader how Zenobias constantly changing flower had undergone a cold and bright transfiguration when the flower became a permanent jewel. The flower is now bright because it sparkles but cold because it no longer has the freshness of a natural flower; one that can be plucked. It appears that Coverdale has missed his chance at fulfilling one of his earliest ambitions. Though Coverdale fails to deflower Zenobia, he demonstrates other sexual interests as well. Perhaps the most surprising sexual possibility is with the other male character in The Blithedale Romance, Hollingsworth. On page 42, the desperate, apparent, heterosexual Coverdale finds himself looking for the feminine qualities of Hollingsworth. He says, There

was something of a woman moulded into the great, stalwart frame of Hollingsworth; nor was he ashamed of it, as men often are of what is best in them . . . I knew it well. Coverdale continues: Methought there could not be two such men alive as Hollingsworth. There never was any blaze of a fireside that warmed and cheered me, in the down-sinkings and shiverings of my spirit, so effectually as did the light out of those eyes, which lay so deep and dark under his shaggy brows (Hawthorne 42). Coverdales line, there could not be two such men alive as Hollingsworth says that he has probably never felt attraction to another the man the way he feels attraction to Hollingsworth. Though a classic reader might assume Coverdales affections are platonic at most, the contemporary reader, well informed about bisexuality and homosexuality, would see this as another sexual desire that goes unfulfilled for Coverdale. Coverdales descriptions of Hollingsworth are not necessarily emotional, but they are physical; Coverdale talks about how nothing warmed and cheered him like Hollingsworths eyes. In this moment, Coverdales desperateness to have sex is awakened at the possibility of it in any form and with any person. Here, Coverdale tries to find the woman in Hollingsworth just in case the opportunity for a sexual encounter comes about, which it never does. Moreover, perhaps the most intriguing character besides Coverdale, even if only for her role in Coverdales final confession, is Priscilla. At the end of the novel, Coverdale admits that he loved Priscilla, and there is at least evidence to show that he was sexually attracted to her. As was mentioned above, Coverdale had moments where he took time to describe the developing body of Priscilla. On page 72, he describes her as now grown and budding and blossoming. The latter two analogies again play into the flower/deflower sexual reference. On page 73, he describes her small as having a bloom. His descriptions of her attractive physical features

demonstrate his willingness and even eagerness to have Priscilla in a sexual way. Now that she is dead, he cannot fulfill these desires. Further examples of Coverdales sexual desires for Priscilla come on pages 71 and 73. On page 71, Coverdale takes it upon himself to save her from loving Hollingsworth. Coverdale explains how Priscilla is a girl in need and compares her to the damsel in distress that is so common in folklore: When a young girl comes within the sphere of such of a man, she is as perilously situated as the maiden whom, in the old classical myths, the people used to expose to a dragon. If I had any duty whatever, in reference to Hollingsworth, it was, to endeavor to save Priscilla from that kind of personal worship which her sex is generally prone to lavish upon saints and heroes. It often requires but one smile, out of the heros eyes into the girls or womans heart, to transform this devotion, from a sentiment of the highest approval and confidence, into passionate love. (71) Coverdales analogy demonstrates his own desires to save the maiden from the dragon. Though he admits his love for Hollingsworth on the previous page, he himself is in need of a conquest. Coverdales sexual frustrations have carried him as far as playing a game with Priscilla where he will try to be the knight in shining armor, so to speak. Coverdale is certainly not ignorant to the fact that his readers know what the stereotypical maiden left exposed to the dragon looks like; she is often very beautiful. Coverdales adventure is yet another way for him to attempt to relieve his sexual tension. On page 73, Coverdale continues to describe Priscilla in a way that makes her out to be someone or somethings prey again (in the previous paragraph, she was the prey of the dragon). He talks about the animal in Priscilla and how it turns him on:

After she had been a month or two at Blithedale, her animal spirits waxed high, and kept her pretty constantly in a state of bubble and ferment, impelling her to far more bodily activity than she had yet strength to endure. She was very fond of playing with other girls, out-of-doors. There is hardly another sight in the world so pretty, as that of a company of young girls, almost women grown, at play, and so giving themselves up to their airy impulse that their tiptoes barely touch the ground. (73) This fantasy playing out for the readers thanks to Coverdales voyeuristic nature demonstrates how much sex he is missing. Like an old man who can only watch the young ladies and dream of more youthful days, Coverdale, in a sense, spies of these women, gawking at how pretty they are. If Coverdale had sexual partner, perhaps he would not have spend his time concentrating so deeply on women frolicking around outside. Coverdales interpretations of his fellow characters in The Blithedale Romance lead to the conclusion that he was deprived of sex and therefore was sexually frustrated. From the first page of the novel, where Coverdale admits that he is a bachelor and that he attends exhibitions (whatever they may be) of veiled ladies (or the Veiled Lady); through his descriptions of Zenobia and her ever present yet constantly updated flower which is eventually replaced by a permanent one; to a near sexual encounter by the fire with Hollingsworth; to the adventure of winning attempting to win Priscillas love, Coverdale finds himself alone and frustrated at the endin love with a girl whom he can never have now that she is dead. Coverdales sexual frustrations lead him to, at times, show the reader parts of the three other main characters that the reader may not need to see. In the mind of the contemporary reader, the final proclamation is not necessary, though it not a surprising conclusion coming from a narrator who has not had enough intercourse with close friends to suffice and to make his conclusions seem rational.

Work Cited: Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Blithedale Romance, Penguin Books, New York, 1986.

You might also like

- Aleister Crowley, Sexual LiberatorDocument4 pagesAleister Crowley, Sexual LiberatorMogg Morgan100% (1)

- The Prophetic QualitiesDocument5 pagesThe Prophetic QualitiesClara RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Femininity in The Duchess of MalfiDocument8 pagesFemininity in The Duchess of MalfiZahra BarancheshmehNo ratings yet

- Kafka's Metamorphosis - An AnalysisDocument8 pagesKafka's Metamorphosis - An AnalysisArghya Chakraborty100% (1)

- Symbolism and AllusionDocument12 pagesSymbolism and AllusionAmorBabe Tabasa-PescaderoNo ratings yet

- Theme of Religion in 'Dracula'Document2 pagesTheme of Religion in 'Dracula'Miss_M90100% (5)

- Mrs Dalloways Stream of ConsciousnessDocument11 pagesMrs Dalloways Stream of Consciousnessmahifti93% (14)

- For There She Was - Dissolution and Unity in Virginia Woolf's Novel Mrs. DallowayDocument9 pagesFor There She Was - Dissolution and Unity in Virginia Woolf's Novel Mrs. DallowayMaria Carolina AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Into TypeDocument114 pagesMathematics Into TypeSimosBeikosNo ratings yet

- Roald Dahl' S Nonsense Poetry: A Method in MadnessDocument8 pagesRoald Dahl' S Nonsense Poetry: A Method in MadnessImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Answers To Quiz No 19Document5 pagesAnswers To Quiz No 19Your Public Profile100% (4)

- Isolation & Struggle in 'The Handmaid's Tale'Document3 pagesIsolation & Struggle in 'The Handmaid's Tale'Kate Turner100% (2)

- Harry Lavender EssayDocument3 pagesHarry Lavender EssayTanishNo ratings yet

- Hypnosis ScriptDocument3 pagesHypnosis ScriptLuca BaroniNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person: Presented By: Mr. Melvin J. Reyes, LPTDocument27 pagesIntroduction To Philosophy of The Human Person: Presented By: Mr. Melvin J. Reyes, LPTMelvin J. Reyes100% (2)

- Bleak House Narrative StyleDocument5 pagesBleak House Narrative StyleRose Quentinovna WallopNo ratings yet

- 60617-7 1996Document64 pages60617-7 1996SuperhypoNo ratings yet

- The Angel in The HouseDocument10 pagesThe Angel in The Houseapi-280869491100% (1)

- The Blithedale Romance, Hawthorne Aggressively Confronted For The First Time in HisDocument15 pagesThe Blithedale Romance, Hawthorne Aggressively Confronted For The First Time in HisClaudiuo JehanNo ratings yet

- Blithedale Romance ThesisDocument4 pagesBlithedale Romance Thesisreneecountrymanneworleans100% (2)

- DOC1Document5 pagesDOC1kheymiNo ratings yet

- Literary Research PaperDocument3 pagesLiterary Research PaperNikko San QuimioNo ratings yet

- The Dysmorphic Bodies of Alice in Wonderland: Be A Little Girl, As The Choice of His Pen Name Goes To ShowDocument12 pagesThe Dysmorphic Bodies of Alice in Wonderland: Be A Little Girl, As The Choice of His Pen Name Goes To Showমৃন্ময় ঘোষNo ratings yet

- JOE ATWILL - The Freemason in The RyeDocument29 pagesJOE ATWILL - The Freemason in The Ryebizboz1000No ratings yet

- Poor Miss Finch by Wilkie Collins - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)From EverandPoor Miss Finch by Wilkie Collins - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Androgyny and HomosocialityDocument3 pagesAndrogyny and HomosocialityFlorencia ZurbrikggNo ratings yet

- Creeley On WoolfDocument4 pagesCreeley On Woolfmigo_phonoNo ratings yet

- The Solitude of Virginia WoolfDocument6 pagesThe Solitude of Virginia WoolfrienNo ratings yet

- Dejection ShitDocument7 pagesDejection Shitfor jstorNo ratings yet

- Assignment Stream of ConsciousnessDocument6 pagesAssignment Stream of ConsciousnessChan Zaib CheemaNo ratings yet

- Luke Baldwin's Vow and Moriey Callaghan's VisionDocument13 pagesLuke Baldwin's Vow and Moriey Callaghan's VisionTú Quỳnh Nguyễn ĐặngNo ratings yet

- Clandestine Happiness Postword "A Thread Above The Abyss"Document5 pagesClandestine Happiness Postword "A Thread Above The Abyss"Caio MNo ratings yet

- Dark Lord: The First Tome of the Chronicles of Greywolf and the GoddessFrom EverandDark Lord: The First Tome of the Chronicles of Greywolf and the GoddessNo ratings yet

- Family and Love: The Dichotomy and Power of Connection in "Klara and The Sun" and "Water"Document5 pagesFamily and Love: The Dichotomy and Power of Connection in "Klara and The Sun" and "Water"pantack72No ratings yet

- Design and Truth in AutobiographyDocument7 pagesDesign and Truth in AutobiographyArunima ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- The Enchanted World of The Color PurpleDocument7 pagesThe Enchanted World of The Color PurpleScott MillerNo ratings yet

- Love and Conversion in Mrs. Dalloway - Blanch GelfantDocument18 pagesLove and Conversion in Mrs. Dalloway - Blanch GelfantLuciana GhanemNo ratings yet

- Catcher in The Rye - PresentationDocument9 pagesCatcher in The Rye - PresentationBethanyNo ratings yet

- The Gift of Loneliness - Alice Walkers - em - The Color Purple - emDocument6 pagesThe Gift of Loneliness - Alice Walkers - em - The Color Purple - emPriyaNo ratings yet

- Geoffrey Wall: Thinking With Demons: Flaubert and de SadeDocument28 pagesGeoffrey Wall: Thinking With Demons: Flaubert and de Sadedon biosNo ratings yet

- Heart of Darkness Literary Analysis EssayDocument7 pagesHeart of Darkness Literary Analysis Essayapi-439121896No ratings yet

- Fate Magazine September 1949 Men of MysteryDocument7 pagesFate Magazine September 1949 Men of MysteryRavi KumarNo ratings yet

- English Writing 1900-1960Document5 pagesEnglish Writing 1900-1960natassayannakouli100% (2)

- Britlitresearchpaper KatherinecurlessDocument9 pagesBritlitresearchpaper Katherinecurlessapi-315541105No ratings yet

- Zelazny - Essai Sur - EN - ZelaznyDocument6 pagesZelazny - Essai Sur - EN - ZelaznyscribdNo ratings yet

- Rachel Carson - Breaking The SilenceDocument7 pagesRachel Carson - Breaking The Silencecarolyn6302No ratings yet

- Beautiful Words About WomenDocument6 pagesBeautiful Words About WomenTheVineNo ratings yet

- Tirra Lirra by The River AnalysisDocument6 pagesTirra Lirra by The River Analysisrohit sebastian asusNo ratings yet

- Superficial Relationships - A DOLLS HOUSE & DORIAN GRAY COMPARISONDocument3 pagesSuperficial Relationships - A DOLLS HOUSE & DORIAN GRAY COMPARISONEmilia WilliamsNo ratings yet

- The Weavers: a tale of England and Egypt of fifty years ago - CompleteFrom EverandThe Weavers: a tale of England and Egypt of fifty years ago - CompleteNo ratings yet

- "Mrs. Dalloway" "The Waves" "To The Lighthouse" "A Room of One's Own"Document18 pages"Mrs. Dalloway" "The Waves" "To The Lighthouse" "A Room of One's Own"Наталия КарбованецNo ratings yet

- The Art of Detection in A World of ChangDocument32 pagesThe Art of Detection in A World of ChangM. Abdul SalamNo ratings yet

- Veritas CloudPoint Administrator's GuideDocument294 pagesVeritas CloudPoint Administrator's Guidebalamurali_aNo ratings yet

- K3VG Spare Parts ListDocument1 pageK3VG Spare Parts ListMohammed AlryaniNo ratings yet

- Science Project FOLIO About Density KSSM Form 1Document22 pagesScience Project FOLIO About Density KSSM Form 1SarveesshNo ratings yet

- Florida v. DunnDocument9 pagesFlorida v. DunnJustice2No ratings yet

- Nandurbar District S.E. (CGPA) Nov 2013Document336 pagesNandurbar District S.E. (CGPA) Nov 2013Digitaladda IndiaNo ratings yet

- The BreakupDocument22 pagesThe BreakupAllison CreaghNo ratings yet

- Chain of CommandDocument6 pagesChain of CommandDale NaughtonNo ratings yet

- IndianJPsychiatry632179-396519 110051Document5 pagesIndianJPsychiatry632179-396519 110051gion.nandNo ratings yet

- 123456Document4 pages123456Lance EsquivarNo ratings yet

- Reflection On Sumilao CaseDocument3 pagesReflection On Sumilao CaseGyrsyl Jaisa GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Alice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland)Document11 pagesAlice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland)Oğuz KarayemişNo ratings yet

- La Fonction Compositionnelle Des Modulateurs en Anneau Dans: MantraDocument6 pagesLa Fonction Compositionnelle Des Modulateurs en Anneau Dans: MantracmescogenNo ratings yet

- Pre T&C Checklist (3 Language) - Updated - 2022 DavidDocument1 pagePre T&C Checklist (3 Language) - Updated - 2022 Davidmuhammad farisNo ratings yet

- StatisticsAllTopicsDocument315 pagesStatisticsAllTopicsHoda HosnyNo ratings yet

- Psychology and Your Life With Power Learning 3Rd Edition Feldman Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument56 pagesPsychology and Your Life With Power Learning 3Rd Edition Feldman Test Bank Full Chapter PDFdiemdac39kgkw100% (9)

- CA-2 AasthaDocument4 pagesCA-2 AasthaJaswant SinghNo ratings yet

- Employer'S Virtual Pag-Ibig Enrollment Form: Address and Contact DetailsDocument2 pagesEmployer'S Virtual Pag-Ibig Enrollment Form: Address and Contact DetailstheffNo ratings yet

- Different Types of Classrooms in An Architecture FacultyDocument21 pagesDifferent Types of Classrooms in An Architecture FacultyLisseth GrandaNo ratings yet

- Diane Mediano CareerinfographicDocument1 pageDiane Mediano Careerinfographicapi-344393975No ratings yet

- Test 1Document9 pagesTest 1thu trầnNo ratings yet

- W 26728Document42 pagesW 26728Sebastián MoraNo ratings yet

- Account Statement From 1 Jan 2017 To 30 Jun 2017Document2 pagesAccount Statement From 1 Jan 2017 To 30 Jun 2017Ujjain mpNo ratings yet

- 1 Introduction To PPSTDocument52 pages1 Introduction To PPSTpanabo central elem sch.No ratings yet

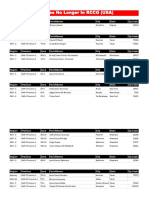

- Churches That Have Left RCCG 0722 PDFDocument2 pagesChurches That Have Left RCCG 0722 PDFKadiri JohnNo ratings yet

- Fry 2016Document27 pagesFry 2016Shahid RashidNo ratings yet