Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Conceptions of The City-Region - A Critical Review - Simin Davoudi

Uploaded by

Luis StephanouOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Conceptions of The City-Region - A Critical Review - Simin Davoudi

Uploaded by

Luis StephanouCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/250074316

Conceptions of the City-Region: A Critical Review

Article in Urban Design and Planning · January 2008

DOI: 10.1680/udap.2008.161.2.51

CITATIONS READS

37 373

1 author:

Simin Davoudi

Newcastle University

115 PUBLICATIONS 2,369 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

ESPON - Territories and low-carbon economy View project

Tackling Low Standards in Environmental Quality View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Simin Davoudi on 11 November 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Proceedings of the Institution of

Civil Engineers

Urban Design and Planning

Month 2008 Issue DP?

Pages 1–10

doi

Paper 800019

Received 19/10/2007

Accepted 28/04/2008

Simin Davoudi

Keywords: history/public policy/ Professor of Environmental

reviews Policy and Planning, Newcastle

University, UK

Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review

S. Davoudi BArch, MPhil, MRTP, AcSS

Since the 1990s, there has been a remarkable resurgence of McKenzie, an American sociologist, was pointing out that ‘the

the concept of the city-region in both academic and policy metropolitan (or city) region . . . is primarily a functional entity.

communities. In broad terms, the concept articulates the Geographically it extends as far as the city exerts a dominant

relationships between the city and its environs. While the influence’.6

city-region’s rising popularity is recent, its origin is not. However,

despite its long history, the concept of the city-region does not However, despite its long history the concept of the city-region

enjoy a common definition, neither in its use as an analytical term does not enjoy a common definition, neither in its use as

nor in its upsurge as a political one. While there are clear linkages an analytical term nor in its upsurge as a political one.

between the two, the main focus of this review is on the city- Analytically, it represents different spatial entities depending

region as an analytical construct. Hence, the paper provides a on how it has been arrived at methodologically. Politically, it

critical review of the different methodologies that have been means different things depending on the type of policy agenda

employed over the last 50 years for defining and mapping the it serves. In practice, the concept is frequently used simply to

city-region. This work shows that, despite their variations, they refer to the areal extent of a metropolitan area. While there are

share two common features—an urban-centric view of the city- clear linkages between the analytical and political usages of the

region and an economically driven approach to its definition. concept, the main focus of this review is on the city-region as

These are further elaborated by focusing on the prevailing an analytical construct. As such, a key contribution of the

conception of the city-region as a functional economic space and concept to spatial thinking is its departure from a preoccupa-

the dominant top-down approach to delineate the boundaries of tion with the physical structure of the city and the urban form

what is known as the functional urban region. per se towards a focus on the relational dynamics of the social

networks and urban functions that often transcend the bounded

1. INTRODUCTION: THE ASCENDANCE OF THE perceptions of space. Hence, the contemporary relevance and

CITY-REGION significance of the city-region concept lies in its potential—

After about thirty years of policy focus on urban (particularly firstly, to evoke a relational understanding of space and place

inner urban) areas, the 1990s saw a shift of emphasis towards in policy and practice; secondly, to encourage researchers to

the city-region. Indeed, the concept of the city-region, which in seek new methodologies for capturing the less tangible

broad terms articulates the relationships between the city and interconnections that define the virtual contours of what

its environs, has witnessed a remarkable resurgence in both Castells7 called the space of flows.

academic and policy communities. Its revival is not only a

reincarnation of an analytical construct to understand complex 2. THE CITY-REGION INTERACTIONS

spatial relations, but also a manifestation of a political move There is an increasing recognition that city-regional

towards new regionalism.1 This has been coupled with the relationships are dynamic and evolve over time, spanning

rescaling of state intervention to intermediate levels such as the multiple boundaries in a variable geometry of overlapping

city-region.2 spaces with flexible and blurred contours. Some fifty years ago,

Duncan8 noted that ‘there is no such thing as a single, uniquely

While the city-region’s rising popularity is recent, its origin is defined “region” that manifests a full spectrum of city-regional

not. The idea that the city cannot be understood fully by relationships’. Indeed, city-region relations constitute a

reference only to its administrative boundaries has a long complex web of visible and invisible multi-directional flows of

history. The term itself is thought to have been coined by not only economic but also social, cultural and environmental

Robert Dickinson in 19473 but the concept was used well before activities. These include flows of, for example

that in both research and planning practices. For example, as

early as 1909, the Chicago Plan was already promoting a (a) people (daily commuting to work, shopping and leisure;

regional vision of the city that extended well beyond its non-daily commuting for cultural, entertainment and

administrative boundaries.4 Similarly, in 1915 Geddes5 used the recreational activities; migration)

notion of conurbation to advocate the need for planning to (b) goods (manufacturing and semi-processed materials

take into account the resources of regions in which historic but between firms)

rapidly spreading cities are situated. Furthermore, in 1933, (c) services (banking, educational, health, business)

Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch 1

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 1 5/14/2008 2:30:27 PM

(d) capital and assets (investment, taxes, land ownership, 4. THE CITY-REGION AS A FUNCTIONAL

property rights) ECONOMIC SPACE

(e) waste and pollution (solid waste, emissions, water Conceptualising the city-region as a functional economic space

pollution) (as pioneered by Berry et al.13) has remained an enduring and

(f) environmental resources (water, minerals) powerful spatial imagination. For example, a recent study

(g) knowledge (technical information, social ideas and commissioned by the UK Government to produce a ‘framework

experiences) for city-regions’ states that ‘conceptual underpinning is clear:

(h) social norms, values, lifestyles and identities. city-regions are essentially functional definitions of the

economic . . . “reach” of cities’.14 Within this perspective, the

Through these interactions, cities and regions potentially share city-region is depicted as a largely self-contained and

a mutually reinforcing relationship. Furthermore, each of these integrated economic entity, commonly known as the functional

linkages creates its own spatial imaginaries and functional urban region (FUR).

boundaries that do not always overlap. The outcome is a

complex web of interactions and a multiplicity of boundaries. The concept of the FUR was first developed in the USA as

As Hawley, an American sociologist, suggests, ‘. . . the a way of moving away from an earlier population-based

boundaries of the modern community, instead of being precise concept of the metropolitan district that referred to urban

lines, are blurred, if not indeterminate. Each index yields a agglomerations with more than 200 000 inhabitants. The shift

different description of a community’s margins . . . nothing less took place when Gras,15 an economic historian, used economic

than a combination of indexes is adequate for the fullest rather than spatial criteria to identify fourteen metropolitan

approximation to an appropriate boundary’.9 areas in North America. Later, the notion of the ‘metropolitan

area’ was formally adopted by the US Bureau of the Census in

1950—called the standard metropolitan statistical area (SMSA)

However, despite this long-standing recognition of the

and referring to areal units of over 50 000 population. The

complexity and emergence of the city-region’s spatial struc-

defining characteristic of the ‘metropolis’ was considered to be

tures, attempts to define the city-region have remained almost

the commuting pattern of the workforce, which was assumed to

entirely focused on economic relationships that in turn are

be radial from the periphery to the centre(s) where jobs were

narrowly defined by labour market areas, using journey-to-

located. Such a definition was clearly reflected in McKenzie’s

work data. This, as will be discussed later, has led to the

description of the metropolitan area: ‘structurally, this new

dominance of an urban-centred and economically driven

metropolitan regionalism is axiate in form. The basic elements

concept of the city-region.

of its patterns are centres, routes and rims’.6 In the UK, the

notion of conurbation, coined by Geddes5 in 1915 and further

3. DEFINING THE CITY-REGION

developed by Fawcett16 in 1932, was spatially rather than

functionally defined. Fawcett16 argued that

The concept of the city-region, like all concepts, is a mental

construct. It is not, as some planners and scholars seem to think,

One of the most important and striking developments in the

an area which can be presented on a platter to suit their general

growth of the urban population…has been the appearance of a

needs.10

number of vast urban aggregates, or conurbations… These have

usually been formed by the simultaneous expansion of a

Since the 1950s, numerous studies have attempted to define the

number of neighbouring towns, which have grown out towards

components of the city-region; identify, measure and map its each other until they have reached a practical coalescence in

boundaries; and understand the interactions between its one continuous urban area.

constituent parts. Despite their variations they share two

common features. Firstly, they portray an urban-centric Fawcett defined seven conurbations in Britain that more or less

conception of the city-region that puts emphasis on the city, corresponded to those that were later delineated by statisticians

sometimes at the expense of neglecting the region. Secondly, in the General Register Office (GRO) using the 1951 census. For

they represent an economically driven approach to city-region them, ‘the conurbation generally should be a continuous built

definition in which the dominant economic flows determine up area’ with some consideration being given to population

the extent of the city-region. Exceptions to these do exist but density.17 However, they adhered strictly to the existing

are rare and more recent. This is not to suggest that the administrative boundaries in defining their limits.10 So, at the

urban-economic approach to city-region definition has gone time when the British statistical authorities were using the

unchallenged. On the contrary, while its urban-centric dimen- concept of conurbation defined largely on the basis of the

sion has been questioned by the changing patterns of work, physical extent of a city, on the other side of the Atlantic,

mobility and lifestyle in rural areas,11 its economic determinism SMSAs put functional integration at the centre of the definition

has been disputed in the face of growing recognition of the of metropolitan areas. Meanwhile, in other parts of Europe

ecological functions of cities and their environmental footprints researchers were drawing on criteria similar to those used to

on their hinterlands and beyond.12 However, it remains the case define the SMSA to delineate city-regions. A notable example

that the most common and deeply embedded interpretation is Carol’s definition of Zurich city-region in 1956.18 Given the

of the city-region is its conceptualisation as a functional strong influence of Christaller’s central place theory19 on the

economic space. The remainder of this paper will provide a continent, Carol combined two approaches (one based on

historical review of this interpretation and an outline of the commuting data to define a city-region and the other based on

different methodologies that have been used to map its spatial the range of services to define a hierarchy of service centres) to

structure. map the arrangement of central places in the city-region of

2 Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 2 5/14/2008 2:30:27 PM

Zurich. He then argued that a planned decentralisation of In the top-down deductive approach, analyses start from a

activities should be guided by this framework. pre-determined set of ‘cities’ as nodes or destinations for

economic flows and then move out to assign other areas to

By the 1970s, the functional approach was introduced in the them.27 These cities (nodes) are selected on the basis of a

UK through the study of standard metropolitan labour areas specified set of functions, population size, economic

(SMLAs) for England and Wales by Hall and his team.20 Both performance (often measured by gross domestic product),

the SMSA and SMLA consist of the historic city plus its accessibility and connectivity, intensity of financial and

commuting hinterland, instead of being limited to the business services, etc. Depending on the weight given to the

contiguous built-up areas centred upon a particular city. The criteria for the selection of nodes, the numbers of cities, and

functional approach to the city-region definition was advanced hence the frequencies of the city-regions, reduce or increase.25

by further studies21–24 and as part of a pan-European research While a classic example of the top-down definition is the

programme on spatial planning called ESPON 2006 (European official definition of SMSAs in the USA, the approach is also

Spatial Planning Observation Network (www.espon.eu)). As will used in countries such as Canada, France (urban areas),

be discussed later, ESPON has had limited success due to a lack Germany and Portugal,26 as well as in pan-European studies

of consistent and comparable data and methodologies.

such as ESPON 2006.

As regards the utilisation of the FUR in policy and practice,

In the bottom-up inductive approach, city-regions emerge from

Parr25 argues that ‘the importance of the CR [city-region] as an

the full set of commuting data through an algorithm that

organising element in the space economies of developed

simultaneously optimises the boundaries on the basis of a

nations has long been recognised. Until relatively recently,

size of employment criterion and a minimum threshold of

however, this recognition was largely confined to academic

self-containment of flows to workplaces.14 This approach has

circles’. This view is confirmed by evidence from a survey

become feasible only recently as a result of advances in data

conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) in 2002.26 The survey reveals that many manipulation and computation. It still remains an exceptional

developed nations (e.g. Japan, Mexico, Korea, Spain and feature of a landscape that is dominated by the traditional

Turkey) do not use the FUR for organising their national space top-down definition of the FUR (see Eurostat28 for a cross-

economies. It also shows that official recognition of the FUR as national review). The most notable attempt to adopt the

the spatial unit for policy implementation varies considerably bottom-up approach is the work undertaken by Coombes et

from one country to another. In some countries, such as al.29 Different variations of this approach are also used in

Austria, Denmark and Switzerland, FURs are used for the countries such as Finland, France (for defining employment

implementation of policies related mainly to labour markets areas) and Italy.26 More recently, the application of aggregative

and transport. In other countries, e.g. Finland, France, Ger- computer modelling, similar to that used in the bottom-up

many, Italy and the UK, FURs, rather than administrative units, approach, has been used to define housing market areas in the

are used to delineate areas that may qualify for national or UK.

European aid. In Norway, the concept of the FUR has played a

significant role in discussions on regionalism. Finally, in In technical terms, while the first approach is nodal and

countries such as Portugal, Sweden, Czech Republic and the non-exhaustive (not covering the whole of the national

USA, FURs are not used at all as the official spatial unit for territory), the second is non-nodal (or multi-nodal) and

policy implementation. Nevertheless, adopting a FUR approach exhaustive.14 The difference in the approaches is clearly

(as a proxy for the city-region) to policy making has remained illustrated in Figs 1 and 2, which show the resulting FURs for

an attractive proposition, particularly in the field of strategic England.

planning where the need for coordination and integration of

investments, policies and programmes is considered to be It can be argued that the top-down approach is underpinned by

critical. Indeed, such arguments have underpinned the current an urban-centric conception of the city-region, while the

debate in the UK over the co-aligning of local government bottom-up approach marks a departure from it, shifting

structures to those of the city-regions. However, as pointed out emphasis from the city to the region. However, while the

by Parr,25 within this perspective the city-region corresponds to

bottom-up approach provides a more inclusive way of

the administrative boundaries of ‘the over bounded metropoli-

understanding the complex flows of commuting across a wider

tan counties’ that were abolished in 1986. He argues that ‘of all

territory, it continues to be an economically driven approach

the contemporary perspectives on the CR, this one is…the least

and largely reliant on travel-to-work analyses. One advantage

in keeping with original spirit of the CR concept, largely

of the non-nodal approach is that it can reveal potential

because concern is with the metropolitan area and not with the

wider region, of which it is the focus’.25 polycentric patterns in the wider region. As Davoudi30 suggests,

promoting the development of such polycentric urban regions,

5. MAPPING FUNCTIONAL URBAN REGIONS where a number of cities of similar size interact with each other

While there have been numerous attempts to define FURs, economically and complement each other in service provision,

emphasis has remained on the city as the node of interactions has become a central objective of the European spatial

and on the economy (or indeed on work-related commuting) as development policy. However, ironically, the approach taken in

the determining function. This has largely shaped (and been the ESPON research to identify European functional urban

shaped by) the methodologies that have been used to map areas uses a top-down rather than bottom-up methodology, as

FURs. Despite their differences, such methodologies fall into will be further elaborated below. Before that, the next section

one of two broad categories—the top-down deductive approach provides an outline of the evolution of the most common (i.e.

and the bottom-up inductive approach.14 the top-down) approach and its key features.

Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch 3

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 3 5/14/2008 2:30:27 PM

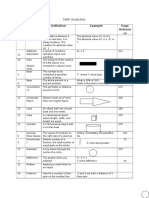

Fig. 1. The top-down approach to city-region definition in England, 2001. This is a nodal approach that starts from a set of pre-

selected cities and hence does not cover the whole of the mapped territory. The map shows the origin areas from which 25% or

more outward commuters travel to one of the destination nodes, and the catchment boundaries for each of the destination nodes.

Source: Robson et al.14

6. THE TOP-DOWN APPROACH have been given various terminologies. The inner area has been

The top-down approach attributes two distinct but interrelated called the core, the centre, the node, the city and the urban

components to the city-region: the inner core area (central tract. The outer area has attracted terms such as the hinterland

urban tract) and the outer surrounding area that is associated by Gras,15 umland (the land around) by the German scholar

with, and sometimes dominated by, the core. The two entities Schöller,31 metropolitan community by Bogue32 and the region

4 Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 4 5/14/2008 2:30:27 PM

Fig. 2. A bottom-up approach to city-region definition in England, 2001. This is a non-nodal approach that does not start from a set

of pre-selected cities and hence covers the whole of the mapped territory. Note that the dividing lines on the map delineate the

functional regions and do not necessarily correspond to administrative boundaries. The 70% self-containment14 refers to the

percentage of commuters not crossing the region’s boundary. Source: Robson et al.14

by McKenzie6 and Dickinson.3 Mumford33 called the city’s can be further divided into two categories—the city settlement

region its field of association or catchment area. More recently, area or the daily commuting area, and the city trade area or the

Parr25 codified these two entities by calling them the ‘C zone’ catchment area for central services.

and the ‘S zone’ to disassociate them from their historical

baggage and to use categories that are ‘exhaustive and An early and striking example of a top-down, urban-centric

mutually exclusive’. According to Dickinson,10 the outer area view of the city-region is portrayed by Bogue32 who, drawing

Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch 5

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 5 5/14/2008 2:30:31 PM

on biological analogies, delineated 67 metropolitan regions in England is in physical terms predominantly rural but in

the USA based on an arbitrary system of decreasing values, socio-economic terms overwhelmingly urban. Indeed, an

beginning with the metropolitan centre as dominant and important feature of the city-region, particularly when based

followed by the hinterland city as sub-dominant, the rural on the bottom-up approach, is its potential to reveal the

non-farm as influent and the rural farm as sub-influent. multi-faceted interrelationships between urban and rural areas

Another example of identifying association zones comes from within a particular spatial context.

work undertaken by Boustedt.34 He defined the city-regions

(stadtregion) of Germany as consisting of a core (one or more 6.2. Delineating the extent of the city-region

contiguous administrative units and associated gemeinden), an There are two ways of defining the extent of the city-region (or

urbanised zone (verstädterte zone), the fringe zone, and the indeed FUR) as a geographical entity: one is through statistical

wider area of umland within which the influence of the city analysis of actual flows and the other is by an approximation

predominates. Mapping the city-region (or more precisely of time–distance from the core.

the FUR) has invariably involved identifying such zonal

arrangements. In the top-down approach, this starts with first 6.2.1. Measuring flows. Dickinson10 argues that ‘. . . the

defining the core and then identifying the extent of its city-region can only be made precise and definable, as a

influence by measuring economic flows to and from the core. geographic entity, by reference to the precise areal extent of

These are elaborated in turn. particular association with the city’. He refers to the fact that

different economic, social, environmental and cultural

6.1. Defining the ‘city’ in the city-region exchanges produce their own spatial structures and hence lead

A top-down approach to map the city-region starts with to multiple and emerging rather than single and static bound-

defining the core city (or the urban tract). Traditionally, this aries. However, the hegemony of economic discourse, which in

has referred to the compact and fairly contiguous built-up area. turn has directed investments into a particular type of data

Such an area has also been a defining feature of conurbation. collection and analysis, has meant that the only city-region

For example, Fawcett16 argued that ‘. . . a conurbation is an area interactions that have proved amenable to measurement and

occupied by a continuous series of dwellings . . . etc., which are mapping are the economic ones. These are often measured by

not separated from each other by rural land’. This approach and flows of people or, more precisely, flows of daily commuters to

its follow up by the GRO in 1956 as well as the American work. This is evident from, for example, an OECD survey of

SMSA were designed partly to distinguish predominantly urban members that concludes ‘the most typical concept used in

areas from predominantly rural ones. In that sense, their defining a functional region is that of labour markets’.26

understanding of ‘conurbation’ was not the same as that of

Geddes.5 His was more consistent with the wider concept of the Within this perspective, after delineation of the core (the city),

city-region as a functional space and came closer to what the extent of the FUR is ‘determined by the inclusion of each

locality having more than a given percentage (as low as 10%)

Friedmann and Miller35 called the urban field. It represented,

of its employed labour force working in the C zone [the core

they argued, ‘. . . a new scale of urban living that will extend

city]’25 and hence commuting from such localities to the core

far beyond existing metropolitan cores and penetrate deeply

on a daily basis. Clearly, the lower the proportion (or the

into the periphery’.

cut-off), the larger will be the extent of the FUR and vice versa.

In technical terms, a low percentage point will cause over-

Meanwhile in France, the notion of urban aggregates was

bounding while a high threshold will lead to under-bounding.

defined (for the 1954 census) as those contiguous communes

In the case of the former, areas whose labour market linkages

that were linked together primarily in terms of family

with the core are not above a certain threshold will be excluded

associations (cadre de l’ existence familiale). Interestingly, this

from the resulting city-region, even if they may be tightly

included the geographic framework in which, for example, connected to it through, for example, environmental, cultural

schools and shops were located but excluded workplaces.36 In or administrative ties. Conversely, when the threshold is low,

Germany, while there were no official definitions of urban the resulting FRU will engulf those cities and towns that fall

areas by census authorities at that time, several studies within the threshold even if they assume historical and political

attempted to define the city-region. A notable example is independence.

Hesse’s work on typologies of gemeinden in southwest Germany

in the 1940s.37 The issue is not a mere technical one and can have

far-reaching implications for spatial planning, investment

Utilising the compactness of urban uses as a criterion remains programmes as well as the development of a sense of place and

at the centre of the statistical definition of the core city as well identity. Indeed, a critical planning issue in the development of

as the distinction between what is urban and what is rural. For regional spatial strategies in the UK has been the conflict over

example, in Finland (in common with other Nordic countries) such boundaries. In the Yorkshire and Humber region for

a built-up area (taajama) refers to a cluster of buildings example, the inclusion of the city of York, which for many

containing at least 200 residents in which the distance between years has assumed an independent historical administrative and

buildings does not exceed 200 m.38 However, given the cultural identity, within the boundary (albeit fuzzy boundary)

diffusion of the urban–rural fringe, the definition of an of Leeds city-region became a contentious issue in the process

urbanised core in terms of continuous urban land uses has of spatial strategy making process.40 Hence, as Dickinson10

become increasingly elusive and in many cases irrelevant.39 As points out, it is important not to overlook the fact that, ‘the city

mentioned previously, definitions of the ‘urban’ based on is a human phenomenon, not simply a bundle of statistics. Its

economic function have grown apart from definitions based on complex relations with its surroundings are as much cultural

physical development. For example, using the terms loosely, and administrative in nature as they are economic’.

6 Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 6 5/14/2008 2:30:35 PM

Indeed, a major criticism of conceptualising city-regions as daily commuting. This, prior to the introduction of public

FURs is its heavy reliance on not only one type of interaction transport in the late 19th century, was considered to be a

(i.e. economic) but also on one economic criterion (i.e. travel to three-mile radius—a distance comfortable for travel by ‘foot

work) for measuring that interaction. As Coombes and Wymer41 and hoof’. In The Modern Metropolis, Blumenfeld46 argued that

argue, such reductionism has been compounded by a lack of the reasonable travel time from the outskirts to the centre had

attention to the differences between labour market areas for to be ‘no more than forty minutes’. Geddes’ rule of thumb for

various social groups. Often, the average commuting distance convenient commuting distance was one hour.5 Whilst most

of the higher order occupational groups (professional and commentators have used the latter as the maximum commuting

managerial) is much longer than that of the lower ones distance, Batten47 argued for the lower limit of half an hour.

(unskilled, manual), leading to more than one city-region More recently, studies undertaken under the ESPON 2006

boundary even for one type of commuting. For instance, while programme48 used a measure of forty five minutes drive time as

on average 40% of the UK’s working population cross at least a proxy for identifying potential functional urban areas across

one administrative boundary during their journey to work Europe. In all these, lines of equal time–distance to and from

(based on the 2001 census), this figure increases for higher the city (isochrones) are used to define the extent of the

skilled and professional workers.42 Furthermore, labour market city-region.

analyses have a limited utility in capturing the economic

relationships of the FUR. For a more inclusive approach, other Whatever is considered a comfortable commuting time, this

non-work trip-generation activities (e.g. journeys to shops, methodology remains arbitrary and suffers from the same

services and leisure facilities) need to be taken into account flawed assumption that was made by Bogue in 1949 when he

despite the difficulties in quantitatively measuring them.43 A mapped metropolitan regions in the USA. He assumed that

notable attempt to embrace the complexities of identifying the accessibility between one centre and another was a basic

boundaries of what are called the ‘localities’ in Britain of the determinant of city-regional relations. The assumption was that

1990s, is the research undertaken by Coombes and colleagues.41 ‘a metropolis can dominate all of the area which lies closer to it

than to any other similar city, even if the other metropolis is

The study shows that when journeys to services are taken into

larger’.32 While proximity may be necessary for the creation of

account, the city-region boundaries will further diverge.

a functional economic space, it is certainly not sufficient.

Having said that, as speed and convenience of travel increase,

An additional complexity arises when housing market areas are

so will the isochrone and hence the extent of the FUR because

brought into consideration. In practice, it appears that ‘the

people can, if other conditions are right, commute further

search areas used by households making residential location

distances within the same time span. A notable example of the

decisions tend to be strongly influenced by their “mental maps”

role of infrastructure in expanding the FUR is the development

of areas with which they are familiar’.14 Such areas do not

of Oresund Bridge between Copenhagen and Malmo, which has

necessary match that of the labour market area,44 hence

led to the creation of a trans-national city-region.

creating yet another boundary for the city-region. As

mentioned earlier, more recent definitions of housing market

Defining the extent of FURs confronts researchers with further

areas in the UK, which use bottom-up analysis, have confirmed challenges when the scale of analysis rises to European level. A

this discrepancy.14 lack of consistent and comparable data and methodologies has

led to the creation of NUTS (nomenclature of statistical

Added to this is the thorny issue of interactions between firms territorial units) by the European Statistical Office (Eurostat).

and businesses, which are crucial in providing a meaningful NUTS classification was introduced in the 1970s in order to

understanding of city-regional economic relationships. In produce regional statistics for the European Union (EU). It was

a recent ambitious attempt to capture such economic relation- given legal status in 2000 and since then has been amended a

ships in ‘mega city-regions’, Hall and Pain45 tried to measure few times, making historical comparison very difficult. The

the interactions between firms and businesses that act as key NUTS classification is based on administrative boundaries as

intermediaries in the knowledge economy, such as advanced defined by each EU country. It includes three ‘regional’ levels

business services, financial institutions, law, accountancy and (NUTS 1–3) and two local levels (local administrative units 1,

management consultancies. Given that many such interactions 2). There are two main drawbacks to this approach. One is that

take place in cyberspace via the internet, measuring them has administrative grounds for defining ‘regions’ differ widely from

proved notoriously difficult if not impossible. What is certain is country to country, making European comparability difficult to

that these interactions take place within a city-regional achieve even in terms of area and population. Hence, for

boundary that is likely to be different from that emerging from example, NUTS 3 regions in Spain (including 52 provincias) are

journey-to-work analyses. Hence, the key message is that there considerably larger than those in Germany (including 439

is no single city-region boundary. Instead, the city-region Kreise).49 The second drawback is that none of the NUTS levels

geometry is best characterised by multiplicity, fuzziness are defined on the basis of functional relations. Hence, in a

and overlaps, manifesting only an approximation of self- recent attempt to identify FURs across 29 countries in Europe,

containment that is likely to vary for different kinds of the ESPON 2006 programme had to use national definitions of

activities, flows and functions. FURs that varied considerably from one country to another.

Based on these definitions, the study identified 1595 ‘functional

6.2.2. Approximating the time-distance. In addition to the urban areas’, out of which 76 were considered to be metropoli-

use of statistical analyses of actual commuting flows, there tan European growth areas (MEGAs). These were selected on a

have also been attempts to map FURs using an approximated top-down basis using population size and significance in terms

time–distance considered to be reasonable or convenient for of

Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch 7

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 7 5/14/2008 2:30:35 PM

(a) economic competitiveness (measured by gross value added Politically, it has become the key justification for channelling

in industry) policy attention, investments and political powers towards the

(b) knowledge base (measured by numbers of university economic growth of major cities, often at the expense of those

students) parts that fall outside the cities’ hinterlands. Gonazales et al.11

(c) accessibility (measured by numbers of airport passengers argue that attentions have been re-directed to the relationships

and volume of port-related freight) between the city (and more precisely the larger city) and

(d) decision making (numbers of headquarters of top 1500 the region rather than to the city-region itself, with the

European firms) consequential neglect of smaller towns and rural areas.

(e) public administration (measured by the highest level of

public administration located there).50 Furthermore, a key shortcoming in the current city-region

agenda is separation of the debate about the city-region as an

It is clear that the methodology and choice of indicators were economic space from discussion on the city-region as an

determined not by a coherent conception of the city-region (or ecological entity. Contemporary city-regions are key sites of

even the FUR) but by the availability of comparable data across consumption of environmental resources and production of

Europe. Such a data-driven approach to research is by no waste. As such, they are engaged in not only economic

means exclusive to the ESPON programme. It is an unfortunate exchanges and distributions of benefits, but also in ecological

side-effect of a desire to widen (rather than deepen) the exchanges and distribution of risks and disadvantages. An

analysis to cover the European territory as a whole in most illustrative example of this is municipal waste management,

European spatial analyses. where city-regional relationships are based largely on

generation of waste in the city and its disposal in the hinter-

7. CONCLUSION land and beyond.55 Critical examination of how these changing

The city-region has enjoyed a widespread resurgence in recent ecological interactions may re-shape our conceptions of the

years in both analytical and political terms. The focus of this city-region and deepen our understanding of the emerging

account has been on the former, aiming to unpack the concept, relational dynamics of the city-region space will therefore

trace its origin and explore its evolution. Particular emphasis

make a valuable contribution in taking the city-regional debate

was placed on a critical review of the methodological

forward.

approaches to the definition of FURs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

While in the last 60 years or so, many approaches have been

A different version of this paper will appear in The Interna-

adopted to define the city-region and map its boundaries, this

tional Encyclopaedia of Human Geography, edited by R. Kitchin

review has shown that, with a few exceptions, the dominant

and N. Thrift, published by Elsevier. The author would like to

concept of the city-region has been urban-centric and econom-

thank the reviewers of this article for their constructive

ic-driven. The supremacy of this urban-economic perspective

comments.

relates partly to the historical evolution of the spatial structure

of the city-region. This, until the mid-20th century, was largely

REFERENCES

influenced by a continuing concentration of population and

1. Special issue on devolution and the English question.

economic activities in the core city in most of the developed

Regional Studies, 2002, 36, No. 7, 715–797.

world. Although this trend began to reverse in the latter part of

2. BRENNER N. Metropolitan institutional reform and the

the 20th century (mainly in parts of Western Europe and North

rescaling of state space in contemporary Western Europe.

America where population and, later, employment began to

European Urban and Regional Studies, 2003, 10, No. 4,

decentralise25), it did not substantially change the urban-

297–324.

economic perspective. Indeed such a view has now been further

3. DICKINSON R. E. City Region and Regionalism. Kegan Paul,

boosted by the re-emergence of cities as the perceived magnets

London, 1947.

for attracting population and economic activities and a

prevailing policy framework based on competitive city- 4. SIMMONDS R. and HACK G. Global City Regions: Their

regionalism.51, 52 It is argued that ‘competitive cities create Emerging Forms. Spon Press, London, 2000.

prosperous regions…through a potential chain reaction which 5. GEDDES P. Cities in Evolution. Williams and Margate,

can follow from a high level commitment to strengthen a city’s London, 1915.

knowledge base as a launch pad for stronger economic 6. MCKENZIE R. D. The Metropolitan Community.

performance and a distinctive external profile’.53 While the McGraw-Hill, New York, 1933.

evidence for such ‘trickle down’ or ‘ripple out’ effects is yet to 7. CASTELLS M. The Rise of the Network Society. Blackwell,

be documented (in fact a recent study has shown that economic Oxford, 1996.

spillover from one city to the surrounding area is highly 8. DUNCAN O. D. Metropolis and Region: Resources for the

contextual and hence hard to generalise54), this argument Future. John Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD, 1960.

continues to frame the debate about the city-region in both 9. HOWELY A. Human Ecology. Xxxxxxxxxx, New York,

analytical and political terms. 1950.

10. DICKINSON R. E. City and Region: A Geographical

Analytically, it has fuelled the dominance of the urban-centric Interpretation. Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd, London,

and economically oriented conception of the city-region. This 1964.

is clearly reflected in the interpretation of the city-region as a 11. GONZALES S., TOMANEY J. and WARD N. Faith in the

FUR and the top-down approach to define its boundaries. city-region? Town and Country Planning, 2006, XX,

No. X, 315–317.

8 Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 8 5/14/2008 2:30:35 PM

12. RAVETZ J. City-region 2020: Integrated Planning for a 32. BOGUE D. J. The Structure of the Metropolitan Community.

Sustainable Environment. Earthscan, London, 2000. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 1949.

13. BERRY B. J. L, COHEEN P. G. and GOLDSTEIN H. Metropolitan 33. MUMFORD L. The City in History. Penguin, Harmondsworth,

Area Definition: A Re-evaluation of Concept and Statisti- 1975.

cal Practice. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC, 1968, 34. BOUSTEDT O. Die stadt und ihr Umland. Raumforschung und

Working Paper No. 28. Raumordnug, 1953, 11, No. X, 20–29.

14. ROBSON B., BARR R., LYMPEROPOULOU K., REES J. and COOMBES 35. FRIEDMAN J. and MILLER J. The urban field. Journal of the

M. G. A Framework for City-regions. Office of the Deputy Institute of American Planners, 1965, XX, No. X,

Prime Minister, London, 2006, Working Paper 1: Mapping 312–320.

City Region. 36. INSTITUTE NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DES ETUDES ECONOMIQUES.

15. GRAS N. S. B. An Introduction to Economic History. Villes et Agglomerations Urbaines. INSEE, Paris, 1955.

Harper, New York, 1922. 37. HESSE P. Grundprobleme der Agrarverfassung. Xxxxxxxx,

16. FAWCETT C. B. Distribution of the urban population of Stuttgart, 1949

Great Britain. Geographical Journal, 1932, 79, No. X, 38. MALINEN P. Rural area typologies in Finland. LEADER

100–113. Workshop on Typology of European Rural Areas,

17. GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE. Census 1951 Report on Greater Luxembourg, 1995.

London and Five other Conurbations. HMSO, London, 39. DAVOUDI S. and STEAD D. Urban–rural relationships: an

1956 introduction and a brief history. Built Environment, 2002,

18. CAROL H. Sozialräuumliche gliederung und planerische 28, No. 4, 269–277.

gestaltung des großstadtbereiches. Raumforschung und 40. DABINETT G. New approaches to space and place in the

Raumordnung, 1956, 14, No. 2/3, 80–92. Yorkshire and Humber Regional Spatial Strategy. In

19. CHRISTALLER W. Die Zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland. Conceptions of Space and Place in Strategic Spatial

Fischer, Jena, 1933. Planning (DAVOUDI S. and STRANGE I. (eds)). Routledge,

20. HALL P., THOMAS R., GRACEY H. and DREWETT R. The Contain- London, to be published.

ment of Urban England: Urban and Metropolitan Growth 41. COOMBES M. G. and WYMER C. A new approach to

Processes or Megalopolis Denied. Allen and Unwin, identifying localities: representing ‘places’ in Britain. In

London, 1973. The Governance of Place: Space and Planning Processes

21. COOMBES M. G, DIXON J. S. et al. Functional regions for the (MADANIPOUR A., HULL A. and HEALEY P. (eds)). Ashgate,

population of Britain. In Geography and the Urban Aldershot, 2001, pp. 51–69.

Environment, Regions in Research and Applications No 5 42. HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE. Devolving Decision-

(HERBERT D. T. and JOHNSTON R. J. (eds)). Wiley, London, Making: 3—Meeting the Regional Economic Challenge: The

1982, pp. 63–112. Importance of Cities to Regional Growth. HMSO, London,

22. HALL P. and HAY D. Growth Centres in the European Urban 2006.

System. Heinemann, London, 1980. 43. GORDON P. and RICHARDSON H. W. Beyond polycentricity: the

23. CHESHIRE P. C. and HAY D. G. Urban Problems in Western dispersed metropolis, Los Angeles, 1970–1990. Journal

Europe: An Economic Analysis. Unwin Hyman, London, of the American Planning Association, 1996, 62, No. 3,

1989. 289–294.

24. TUROK I. and BAILEY N. Twin track cities? Competitiveness 44. MACLENNAN D., GIBB K. and MORE A. Paying for Britain’s

and cohesion in Glasgow and Edinburgh. Progress in Housing. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, 1990.

Planning, 2004, 62, No. X, 135–204. 45. HALL P. and PAIN K. The Polycentric Metropolis: Learning

25. PARR J. Perspectives on the city-region. Regional Studies, from Mega City Regions in Europe. Earthscan, London,

2005, 39, No. 5, 555–566. 2006.

26. ORGANIZATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT. 46. BLUMENFELD H. The Modern Metropolis. MIT Press,

Redefining Territories: The Functional Urban Regions. Cambridge, MA, 1971.

OECD, Paris, 2002. 47. BATTEN D. F. Network cities; creative urban agglomerations

27. DAHMANN D. C. and FITZSIMMONS J. D. (eds) Metropolitan and for the 21st Century. Urban Studies, 1995, 32, No. 2,

Nonmetropolitan Areas: New Approaches to Geographical 313–27.

Definition. US Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC, 48. EUROPEAN SPATIAL PLANNING OBSERVATION NETWORK. ESPON

1995, Population Division working paper 12. 1.1.1 Project: Cities as Nodes of Polycentric Development,

28. EUROSTAT. Study on Employment Zones. Eurostat, Luxem- 2004. See www.espon.eu for further details. Accessed xx/

bourg, 1992, Report E/LOC/20. xx/xxxx.

29. COOMBES M. G., GREEN A. E. and OPENSHAW S. An efficient 49. EUROPEAN COMMISSION. European Urban and Regional

algorithm to generate official statistical reporting areas: Statistics Reference Guide. EC, Brussels, 2005.

the case of the 1984 travel-to-work areas revision in 50. BÖHME K. DAVOUDI S., HAGUE C., MEHLBYE P., ROBERT J. and

Britain. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 1986, SCHÖN P. Territory Matters for Competitiveness and

37, No. X, 943–953. Cohesion: Facets of Regional Diversity and Potentials in

30. DAVOUDI S. Polycentricity in European spatial planning: Europe. ESPON Coordination Unit, Luxembourg, 2006.

from an analytical tool to a normative agenda. European 51. WARD K. and JONAS A. E. Competitive city-regionalism as a

Planning Studies, 2003, 11, No. 8, 979–999. politics of space: a critical reinterpretation of the new

31. SCHÖLLER P. Stadt und Einzugsgebiet. Studium Generale, regionalism. Environment and Planning A, 2004, 36,

1957, 10, No. 10, xx–yy. No. X, 2119–2139.

Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch 9

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 9 5/14/2008 2:30:35 PM

52. SCOTT A. Globalization and the rise of city-regions. 54. COOMBES P. P., DURANTON G. et al. Economic Linkages Across

European Planning Studies, 2001, 9, No. X, 813–826. Space. ODPM, London, 2006.

53. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER. Cities, Regions and 55. DAVOUDI S. Strategic waste planning: the interface between

Competitiveness, Second Report from the Working Group. the ‘technical’ and the ‘social’. Environment and Planning

ODPM, London, 2003. C, 2006, 24, No. 5, 681–700.

10 Urban Design and Planning XX Issue DPX Conceptions of the city-region: a critical review S. Davoudi BArch

UDP-D-07-00003R2.indd 10 5/14/2008 2:30:35 PM

View publication stats

You might also like

- Life Among Urban Planners: Practice, Professionalism, and Expertise in the Making of the CityFrom EverandLife Among Urban Planners: Practice, Professionalism, and Expertise in the Making of the CityNo ratings yet

- Exploring urban design from philosophical and psychoanalytic perspectivesDocument27 pagesExploring urban design from philosophical and psychoanalytic perspectivesAlma Ukhtiani NurhasanNo ratings yet

- Designing Urban Democracy: Mapping Scales of Urban Identity, Ricky BurdettDocument20 pagesDesigning Urban Democracy: Mapping Scales of Urban Identity, Ricky BurdettBrener SxsNo ratings yet

- Ar 451 Module1 6Document33 pagesAr 451 Module1 6Shyra Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Fang 2017Document11 pagesJurnal Fang 2017fadhilah khoirunNo ratings yet

- Urban Agglomeration, An Evolving Concept of An Emerging PhenomenonDocument11 pagesUrban Agglomeration, An Evolving Concept of An Emerging PhenomenongramarianiNo ratings yet

- For Whom Exploring Landscape Design As A Political ProjectDocument5 pagesFor Whom Exploring Landscape Design As A Political ProjectWowkieNo ratings yet

- Overview-of-Urban-and-Regional-Planning-Theories-and-Issues-Implications-to-Architectural-PracticeDocument33 pagesOverview-of-Urban-and-Regional-Planning-Theories-and-Issues-Implications-to-Architectural-PracticeAngelo DongonNo ratings yet

- City Region ReconsideredDocument28 pagesCity Region ReconsideredPaulo SoaresNo ratings yet

- Land 10 01235 v2Document23 pagesLand 10 01235 v2Marica SelenaNo ratings yet

- Basic and Non Basic Activity Economic RegionalDocument17 pagesBasic and Non Basic Activity Economic Regionalsara100% (2)

- Clark UniversityDocument17 pagesClark Universitysyakir akeNo ratings yet

- Status ReportDocument28 pagesStatus ReportNIDHI SINGHNo ratings yet

- Agra in Transition - Globalization and ChallengesDocument16 pagesAgra in Transition - Globalization and ChallengesKapil Kumar GavskerNo ratings yet

- Rural Design and Urban Design: the missing linkDocument9 pagesRural Design and Urban Design: the missing linkCharmaine Janelle Samson-QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- Mapping Urban CapitalismDocument19 pagesMapping Urban CapitalismJavierNo ratings yet

- A Project of ProjectsDocument13 pagesA Project of ProjectsRafaela GretiesNo ratings yet

- 2022 UD Module 1Document20 pages2022 UD Module 1abhiramNo ratings yet

- Lecture No.1 CEDDocument34 pagesLecture No.1 CEDekhtisham ul haqNo ratings yet

- Architecture and Urban Design: Leaving Behind The Notion of The CityDocument33 pagesArchitecture and Urban Design: Leaving Behind The Notion of The CityMariyam SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Dile, Dolly E. Bs Architecture 4A: Ad 417 Introduction Research and ReadingsDocument2 pagesDile, Dolly E. Bs Architecture 4A: Ad 417 Introduction Research and ReadingsMezzy Joyce DelfinNo ratings yet

- 2005 Birch ReviewofPetersonTheBirthofCityPlanningDocument4 pages2005 Birch ReviewofPetersonTheBirthofCityPlanningChukwuemeka Kanu-OjiNo ratings yet

- Journal of Cultural HeritageDocument11 pagesJournal of Cultural Heritagejosefa herrero del fierroNo ratings yet

- Urban DESIGN Unit 1Document34 pagesUrban DESIGN Unit 1RITHANYAA100% (1)

- Urban Design-1: As Land Use, Population, Transportation, Natural Systems, and TopographyDocument18 pagesUrban Design-1: As Land Use, Population, Transportation, Natural Systems, and TopographymilonNo ratings yet

- Alif Gusti RamadhaniDocument17 pagesAlif Gusti RamadhaniAlif gusti R RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Landscape UrbanismDocument4 pagesLandscape UrbanismK.SRI CHAANTHANANo ratings yet

- American Urban ArchitectureDocument12 pagesAmerican Urban ArchitectureGreace Pasache PrietoNo ratings yet

- GSD F2014 - 1503 - The Countryside As A City - Studio Syllabus - 20140827-1Document24 pagesGSD F2014 - 1503 - The Countryside As A City - Studio Syllabus - 20140827-1Mauricio FreyreNo ratings yet

- Urban Design As A Contested FieldDocument4 pagesUrban Design As A Contested FieldPrudhvi Nagasaikumar RaviNo ratings yet

- Where and How Does Urban Design Happen Thought CollectionDocument7 pagesWhere and How Does Urban Design Happen Thought Collectionvince baconsNo ratings yet

- URBAN DESIGN A Deifinition, Approach and Conceptual FrameworkDocument37 pagesURBAN DESIGN A Deifinition, Approach and Conceptual FrameworkLalisa MNo ratings yet

- Messy Urbanism Understanding The Other Cities of A... - (11. Everyday Urban Flux)Document22 pagesMessy Urbanism Understanding The Other Cities of A... - (11. Everyday Urban Flux)lukmantogracielleNo ratings yet

- Apl412 Gumallaoi Judelle v. RNW-MT 01Document6 pagesApl412 Gumallaoi Judelle v. RNW-MT 01Judelle GumallaoiNo ratings yet

- SSE07 Lesson1.2 Urbanreforms2ndsemDocument4 pagesSSE07 Lesson1.2 Urbanreforms2ndsemjlgbaracenaNo ratings yet

- Analysing Chowk As An Urban Public Space A Case of LucknowDocument29 pagesAnalysing Chowk As An Urban Public Space A Case of LucknowAnonymous izrFWiQNo ratings yet

- Urban Forms in Planning and Design by Shashikant Nishant Sharma5Document11 pagesUrban Forms in Planning and Design by Shashikant Nishant Sharma5harsha13486No ratings yet

- Urban Design Process Techniques: Identification, Analysis, Synthesis & ImplementationDocument44 pagesUrban Design Process Techniques: Identification, Analysis, Synthesis & ImplementationsonamNo ratings yet

- 2019 Vic Uag All andDocument15 pages2019 Vic Uag All andJoshua Ekwute IttahNo ratings yet

- City, Which Does Not Go As Far As The Edge City inDocument8 pagesCity, Which Does Not Go As Far As The Edge City inPurushothaman KumaraswamyNo ratings yet

- (JOURNAL) Urban Design and Local Economic DevelopmentDocument9 pages(JOURNAL) Urban Design and Local Economic Developmentcona cocoNo ratings yet

- Urban design fundamentalsDocument65 pagesUrban design fundamentalsVarsha biju100% (2)

- UPD II - IntroductionDocument48 pagesUPD II - IntroductionEdenNo ratings yet

- (Template) Pink Module 2.0Document98 pages(Template) Pink Module 2.0Mia Mones Lunsayan BrionesNo ratings yet

- McFarlane Topology Urban DensityDocument20 pagesMcFarlane Topology Urban Densityzhiyi guoNo ratings yet

- Analysing Extended UrbanizationDocument24 pagesAnalysing Extended Urbanizationonuracar82No ratings yet

- ARC036-Research Work No.2 (Foundation of Planning)Document22 pagesARC036-Research Work No.2 (Foundation of Planning)Lee Bogues100% (1)

- 34 Romice-Pasino HandbookQOLDocument41 pages34 Romice-Pasino HandbookQOLHinal DesaiNo ratings yet

- SPI5715 AssignmentDocument8 pagesSPI5715 AssignmentMarilyn CamenzuliNo ratings yet

- Relationality Territoriality Toward New Conceptualization of CitiesDocument10 pagesRelationality Territoriality Toward New Conceptualization of Citiesduwey23No ratings yet

- Regional PlanningDocument73 pagesRegional Planningaditi kaviwalaNo ratings yet

- Krieger - Where and How Does Urban Design Happen PDFDocument10 pagesKrieger - Where and How Does Urban Design Happen PDFDiego Gómez MartinoNo ratings yet

- Ross Adams Longing For A Greener Present Neoliberalism and The Ecocity 1Document7 pagesRoss Adams Longing For A Greener Present Neoliberalism and The Ecocity 1sam guennetNo ratings yet

- Muir Mapping Landscape UrbanismDocument164 pagesMuir Mapping Landscape UrbanismNoel Murphy100% (3)

- Lecture 1 - Introduction To Urban DesignDocument7 pagesLecture 1 - Introduction To Urban DesignNAYA SCAR100% (1)

- Urban Hacking: The Versatile Forms of Cultural Resilience in Hong KongDocument14 pagesUrban Hacking: The Versatile Forms of Cultural Resilience in Hong KongYoshitomo MoriokaNo ratings yet

- Nodes in SuratDocument7 pagesNodes in SuratSagar GheewalaNo ratings yet

- City Planning and InfrastructureDocument22 pagesCity Planning and InfrastructureSADIA AFRINNo ratings yet

- Research Methods AssignmentDocument9 pagesResearch Methods AssignmentMarilyn CamenzuliNo ratings yet

- Planning and Prospects Chapter Provides InsightDocument27 pagesPlanning and Prospects Chapter Provides InsightRinku MeenaNo ratings yet

- Complex Numbers and The Complex Exponential: Figure 1. A Complex NumberDocument19 pagesComplex Numbers and The Complex Exponential: Figure 1. A Complex NumberHimraj BachooNo ratings yet

- (Note) Area of Surface of RevolutionDocument4 pages(Note) Area of Surface of Revolutionai fAngNo ratings yet

- Mathematics (51) : Class IxDocument3 pagesMathematics (51) : Class IxNikhil SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ansell-Pearson Bergson ProofsDocument12 pagesAnsell-Pearson Bergson ProofsDoctoradoNo ratings yet

- P3 Edexcel Mock QPDocument3 pagesP3 Edexcel Mock QPJonMortNo ratings yet

- Practice Questions On Relative MotionDocument1 pagePractice Questions On Relative Motionmoon007000No ratings yet

- Digital Sundial - WikipediaDocument2 pagesDigital Sundial - WikipediaAri SudrajatNo ratings yet

- Bending A Cantilever Beam PDFDocument7 pagesBending A Cantilever Beam PDFNguyen Hai Dang TamNo ratings yet

- Std03 - Term - I - Maths - EM - WWW - Tntextbooks.inDocument88 pagesStd03 - Term - I - Maths - EM - WWW - Tntextbooks.inmansoorali_afNo ratings yet

- Tute 3 PDFDocument2 pagesTute 3 PDFMike WaniNo ratings yet

- Ackermann SteeringDocument6 pagesAckermann Steeringbangbang63100% (1)

- Physics 10th Edition Cutnell Test Bank 1Document6 pagesPhysics 10th Edition Cutnell Test Bank 1marchowardwacfrpgzxn100% (25)

- Questions On ProjectionsDocument14 pagesQuestions On ProjectionsSeema SharmaNo ratings yet

- CH 6 Differential Analysis of Fluid Flow Part IIDocument78 pagesCH 6 Differential Analysis of Fluid Flow Part IIWaleedNo ratings yet

- Straight Lines Assignment from Bal Bharti Public SchoolDocument2 pagesStraight Lines Assignment from Bal Bharti Public SchoolJEE enius PrepNo ratings yet

- Numericals For MotionDocument2 pagesNumericals For MotionArpit Gaming YtNo ratings yet

- Movement and Topological Space in Japanese ArchitectureDocument4 pagesMovement and Topological Space in Japanese ArchitectureRaluca GîlcăNo ratings yet

- Simple Harmonic Motion and ElasticityDocument105 pagesSimple Harmonic Motion and ElasticityyashveerNo ratings yet

- Engineering Graphics Exam Drawing ProblemsDocument2 pagesEngineering Graphics Exam Drawing ProblemsSalim Saifudeen SaifudeenNo ratings yet

- LECT 9 Ordering PrinciplesDocument43 pagesLECT 9 Ordering PrinciplesRojayneNo ratings yet

- Trigonometry Revision ExamplesDocument16 pagesTrigonometry Revision Examplesnada nadaNo ratings yet

- Chapter: Mechanical - Kinematics of Machinery - Kinematics of Cam Mechanisms CamsDocument25 pagesChapter: Mechanical - Kinematics of Machinery - Kinematics of Cam Mechanisms CamsdhaNo ratings yet

- Preged Math Vocabulary Sorted by TermDocument6 pagesPreged Math Vocabulary Sorted by Termapi-341831401No ratings yet

- Moment of InertiaDocument30 pagesMoment of InertiaNordiea Miller-youngeNo ratings yet

- The Storytelling in Architecture. A Proposal To Read and To Write SpacesDocument9 pagesThe Storytelling in Architecture. A Proposal To Read and To Write SpacesArchiesivan22No ratings yet

- Mechanics I: Tutorial 3Document15 pagesMechanics I: Tutorial 3S.A. BeskalesNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Equations of Motion - 2Document26 pagesAircraft Equations of Motion - 2UNsha bee komNo ratings yet

- Ch. 5 KinematicsDocument11 pagesCh. 5 KinematicsJoanne Aga EslavaNo ratings yet

- Geometric Approaches To Solving Diophantine Equations: Alex J. BestDocument42 pagesGeometric Approaches To Solving Diophantine Equations: Alex J. BestHannah Micah PachecoNo ratings yet