Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Case For Mantegna As Printmaker

Uploaded by

Lubava ChistovaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Case For Mantegna As Printmaker

Uploaded by

Lubava ChistovaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Case for Mantegna as Printmaker

Author(s): Keith Christiansen

Source: The Burlington Magazine , Sep., 1993, Vol. 135, No. 1086 (Sep., 1993), pp. 604-612

Published by: (PUB) Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/885852

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

(PUB) Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to The Burlington Magazine

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KEITH CHRISTIANSEN

The case for Mantegna as printmake

fragmentary

VASARI was not among Mantegna's great admirers.* Con- impression from the Metropolit

ditioned as he was by those twin ideals of hors

facility and - testified to a remarkable range o

catalogue)

experimentation

grazia, he could not help finding Mantegna's manner dry (Figs. 1 and 2).4 For those wh

and laboured and his treatment of drapery somewhat

exhibition in London, where paintings, drawings

wereconsider-

crude.' Yet there was no denying Mantegna's very arranged thematically and chronologicall

able contributions to the history of Italianbeart, andnoting

worth in that at the Metropolitan the pr

concluding his biography of the artist in theshown separately, and that the seven prints trad

1550 edition

attributed

of the Vite he noted that Mantegna 'bequeathed to painting to Mantegna were isolated from th

the difficulty of foreshortening figures seen fromascribed

below to

- a him in the catalogue. This had the eff

difficult and fanciful invention; and the manner phasising the issues of authorship, chronology an

of copper

engraving, truly a most singular convenience; intention that are the focus of this article, whic

by which

the whole world has seen not only the Bacchanal, perhaps be theread as a postscript to the catalogue

Battle of the Sea Monsters, the Deposition from the Cross,

the Entombment, the Resurection with Longinus York

Theshowing.,

first

and St point is that when seen together in

Andrew - works by the said Mantegna - but the gallery the seven engravings did, indeed, seem t

manners

of all other subsequent artists'.2 For him,real group. What, in their still fundamental study

Mantegna's

mastery of engraving was as much a part of Levenson, Oberhuber, and Sheehan described as a

the artist's

ingenio as his mastery of those other difficultiesdevelopment

of art, such from the 'delicate, tonal style' of th

ment

as foreshortening and perspective. Of course, (cat.no.39) to a 'vigorous, linear manner,

Mantegna

did not invent copper engraving, and in his 1568the individual

edition shading lines begin to express plas

well could

Vasari hastened to correct this error. Still, there as chiaroscuro',

be culminating in the Battle

no more eloquent testimony to the prestige the godsgroup

(no.79)

ofand the Virgin of humility (no.48), w

engravings associated with Mantegna enjoyed, firmed.6 Just as importantly, the subjects could b

and there

embracethey

could be no greater justification for the prominence the range of Mantegna's output - a

were accorded in the Mantegna exhibitionnarrative,held at thea devotional theme, an iconic composit

Royal Academy and the Metropolitan Museum ceived di sotto in su", and two mythological narra

last year.3

Vasari's testimony should also remind us thatemulate the artistic language of classical sarc

the modern

tendency to divide the study of the fine arts was, indeed,

by media hasdifficult to avoid feeling that the e

little validity for the renaissance. were actually conceived by Mantegna as a man

his art in

This article is the direct result of my involvement - one

the that addressed an audience reared, a

Mantegna exhibition and the unique opportunity patron Ludovico Gonzaga, on Alberti's ideas i

it afforded

Pictura. The point may seem egregious, but I bel

to study these works on a daily basis. It cannot sufficiently

be emphasised how important the occasion was for an

central to a understanding of the genesis and n

clearer understanding of the engravings, forthese remarkable

the late im- works. It is in the engravin

Entombment,

pressions commonly encountered in print cabinets give the Bacchanals and the Battle of the

but a pale reflection of the tonal richness andwith theirof

subtlety emphasis on expression and dramat

that Mantegna most fully and effectively exploite

execution of the rare, fine examples. At the Metropolitan

three fine impressions of the Entombment - the recommendations

unique first for an historia. As Michael Baxandall

has noted,

state from the Albertina and two of the second state in (that

the Entombment the figure of StJohn functions

from the National Gallery, Washington and as anaAlbertian

second, choric figure, setting the emotional tone

*I should like to acknowledge my indebtedness to many thought-provoking obviously has a bearing on any evaluation of the prints as well as the range of

conversations with Suzanne Boorsch over the period of our involvement in the effects the artist was experimenting with.

Mantegna exhibition. Andrea Bayer, David Ekserdjian and Giovanni Agosti 5The following, partial list of reviews of the exhibition should be noted here:

kindly read and commented on the manuscript. M. WARNER, in the Times Literay Supplement [7th February 1992], pp.14-15;

G. VASARI: Le vite de'pid eccellenti architetti, pittori . ., 1550, ed. L. BELLOSI and A. KUNZ, in the Neue Ziiricher Zeitung [8th-9th February 1992], pp.65-66; R. LIGHT-

A. ROSSI, Turin [1986], p.493: 'Et ancora ch'egli avesse il modo del panneggiar suo BOWN, in Apollo, CXXV [1992], pp.185-89; H.R. TREVOR-ROPER in The New York

crudetto e sottile, a la maniera alquanto secca, e' vi sono perb cose con molto artificio e con Review of Books [28th May 1992], pp.3-4 (less a review than an overview of

molta bonti da lui lavorate e ben condotte'. Mantegna); M. HIRST, inTHE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, CXXXIV [1992], pp.318-

2VASARI, ed.cit. above, p.496, my translation. 21; D. ROSAND, in The New Republic [22ndJune 1992], pp.29-32; A. HAVUM, in Art

3See Andrea Mantegna, exh.cat. Royal Academy of Arts, London and The in America [June 1992], pp.68-78, 125; w. STEDMAN SHEARD, in the Art Journal,

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [1992]. The American edition corrects LI [1992], pp.85-93; c. GILBERT, in The New Criterion [October 1992], pp.47-52;

minor errors in the British edition and incorporates additional colour plates; it c. CERI VIA: 'Un'esposizione per Andrea Mantegna', Civilta mantovana, XXVII

is the edition cited here, and the numbers in parentheses throughout the text [1992], pp.189-94; L. VENTURA: 'Discorrendo di Mantegna. Luci ed ombre

refer to it. degli studi nell'anno della mostra di Londra e New York', loc.cit., pp.198-201;

4In the Washington impression an almost grainy ink creates heavy lines em- G. GOLDNER, in Master Drawings, XXXI, no.2 [1993]; P. EMISON: 'Andrea Mantegna,

phasising contours and contrasts of value, while in the Metropolitan impression a Printmaker?! A Controversy', Print Collectors' Newsletter, XXIII [1992], pp.41-

the inking gives a marvellously tonal effect. Without a detailed, line by line 66. Only the reviews ofRosand, Stedman Sheard and Emison deal at any length

comparison, one might be led to believe that these two impressions were actually with the engravings, but see also the comments of A. GENTILI: 'Mantegna,

different states. A. HIND (Early Italian Engraving, A Critical Catalogue with Complete l'incisione e la Discesa al Limbo', Civiltd mantovana, XXVII [1992]; pp.53-75,

Reproduction of all the Prints Described, London [1948], V, pp.4-5), commented on whose article is in part a response to the exhibition.

such variations in printing, but his observation is worth repeating, since it 6J. LEVENSON, K. OBERHUBER and J.L. SHEEHAN: Early Italian Engravings from the

National Gallery ofArt, exh.cat., Washington [1973], p.168.

604

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER

for the viewer, while the scuttling clouds provide a more

naturalistic explanation for the movement of the draperies

than does Alberti's recommended personification of the

west wind (to a similar end, in the Bacchanal with a wine vat,

no.74, the fluttering ribbons fastening the inscribed tablet

to the branch of an apple tree function as a sort of weather-

cock).7 For Alberti, these details of windswept drapery

and of hair that 'twist around as if to tie itself in a knot'

(as in the Battle of the sea gods), were desirable not only

because they were inherently pleasing, but because they

directly pertained to the artist's task of giving visible form

to 'the movements of the mind' - what he referred to as

the affectiones or affezione (II, 43): the affetti.8 In the Risen

Christ between St Andrew and Longinus (no.45) we find those

effects of foreshortening that so impressed Vasari and, in

the words of Giovanni Santi, 'inganan l'ochio e l'arte fan

gioire'.9 And in the Battle of the sea gods we very likely have

an allegory of artistic envy- an invenzione of exactly the

sort Alberti recommended.10 In short, the prints Vasari

singled out as a conspicuous aspect of Mantegna's legacy

really do provide a summary of the artist's ambitions and

achievement. It hardly seems surprising that, with his

strong sense of artistic identity, Mantegna should have

turned to the nascent art of engraving to publicise himself,

or that his involvement was a temporary one and the sub-

jects treated so purposefully selected."

What I would propose is that the seven engravings

traditionally ascribed to Mantegna be viewed not as the

products of a peculiar excursus by a painter into a secondary

medium, but a coherent and focused project, the germ of

1. Entombment (detail), by Andrea Mantegna. H.2, engraving, 29.9 by 42.2 cm.

which lies in those model-books and albums that were

(whole). (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.).

produced in the workshops of Pisanello, Jacopo Bellini,

Squarcione, and Marco Zoppo (we know, in fact, that

Mantegna had managed to procure just such a model-

book with drawings after ancient sculpture, especially

battles of centaurs, before October 1476).I2 As is pointed

out in the catalogue, Mantegna's engravings were widely

mined by artists in a fashion consistent with this function.13

7M. BAXANDALL: Giotto and the Orators, London [1971], pp.127-34, still provides

the best argument for the importance of the De Pictura for Mantegna's engravings.

'The comments of j. GREENSTEIN (Mantegna and Painting as Historical Narrative,

New York [1992], pp.44-52) on Alberti's notion of the afetti should be read

with extreme caution, since they are based on a very debateable interpretation

of Alberti's text.

9For Santi's text, with its long panegyric on Mantegna, see C. GILBERT: L'Arte

del Quattrocento nelle testimonianze coeve, Florence and Vienna [ 1988], p.120.

'0See M. JACOBSEN: 'The Meaning of Mantegna's Battle of Sea Monsters', Art

Bulletin, LXIV [1982], pp.623-29.

" Ribera presents an analogy for this short-term involvement with printmaking

by a painter.

"2See C. BROWN: 'Gleanings from the Gonzaga Documents in Mantua: Gian

Cristoforo Romano and Andrea Mantegna', Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen

Institutes in Florenz, XVII [ 1973], pp.158-59.

13See pp.39-42, notes 16-17, and pp.45, 213-14, cat.no.45 (where, however, a

notice of Gerolamo Casio in 1506 lamenting the death of 'quello [che] intaglio il

Christo. . .' is incorrectly taken as a reference to Mantegna and his print of

Christ between St Andrew and Longinus: as Suzanne Boorsch reminds me, the

object in question is more likely to be a carved gem than an engraving). See also

the examples cited in HIND, op.cit. at note 4 above, and LEVENSON, OBERHUBER

and SHEEHAN, op.cit. at note 6 above, in the relevant catalogue entries. A

particularly interesting case is presented by the studies after the Entombment in

the so-called Venetian Sketchbook created in the circle of Raphael in the early

years of the sixteenth century: see s. FERINO PAGDEN: Disegni umbri del Rinascimento

da Perugino a Raffaello, exh.cat., Uffizi, Florence [1982], p.196. C. LLOYD ('A

Short Footnote to Raphael Studies', THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, CXIX [1977],

pp.113-14) has demonstrated that Raphael turned not only to Mantegna's

Entombment for his painting in the Villa Borghese but to the Bacchanal with

2. Entombment (detail), by Andrea Mantegna. H.2 (fragmentary), engraving.

Silenus, thus suggesting a full study of Mantegna's prints - something we would

expect, given his father's high opinion of the Paduan artist. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

605

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER

For the provincial Matteo Cesi, working in Belluno in the

1480s, the Risen Christ between Longinus and St Andrew provided

a means of updating two altar-pieces (both in the former

Bode Museum, Berlin). About the same time, in the late

1480s, the young Cima da Conegliano made repeated

reference to the same engraving for the poses of Sts Peter

and John the Baptist in his polyptych at Olera, of St Roch

in the altar-piece in the Brera, Milan, and of St John the

Baptist in the altar-piece at Conegliano of 1492-93.14

Mantegna's engraving also lies behind Michele da Verona's

frescoed figure of St Andrew in the church of S. Anastasia

in Verona. For the brilliantly gifted Ercole de' Roberti,

working between 1478 and 1486 in the Garganelli Chapel

w

in S. Petronio in Bologna, Mantegna's Entombment was an

obvious starting point for his Crucifixion (destroyed, but

known both through a compositional drawing in the Kupfer-

stichkabinett, Berlin, illustrated in the catalogue, p.39

and a later copy of the fresco itself); the engraving served

the same purpose for Agostino de'Fonduli's terracotta

Pieta of 1483 in S. Satiro, Milan. 15 Perhaps a decade or so

later Riccio looked to the Entombment and the Risen Christ

for motifs for a bronze plaquette, just as he turned to

Mantegna's Battle of the sea gods in the creation of a bronze

3. Virgin and Child with St

statuette of a triton and nereid and for the decoration of century. Enamelled glass

of Art, New York).

the Paschal Candlestick in the Santo, Padua. 16

Typical of the various compositional uses to which these

homage

prints were put is the transformation of the Bacchanal with (the pain

lection).

a wine vat into a miniature of the Entombment by the Veronese

miniaturist Francesco dai Libri around 1480 (Courtauld

Mantegna's engravings may never have achieved the

Collection, London), and the reappearance of figures ubiquity

from of Marcantonio Raimondi's prints after Raphael,

the Battle of the sea gods in the terracotta frieze onbutthe

by the early sixteenth century the shelves of many a

Palazzo Mozzanica in Lodi (usually dated around 1488 humanist's study were decorated with a version in bronze

and sometimes ascribed to Agostino de'Fonduli).7 Diirer,

of one of the sea monsters in the Battle of the sea gods, while

by contrast, looked to the Battle of the sea gods anda the

private oratory might contain, among its decorations, a

Bacchanal with Silenus as a lexicon of the classical style in plaque of the Emtombment (Museo Civico, Padua);

maiolica

his well-known drawn copies of 1494. At the turn ofabout thethe same time the Virgin of Humility was adapted as

the enamelled decoration of a glass flask (Fig.3).18 The

century, in a devotional painting in the Museo del Castel-

vecchio, Verona, Domenico Morone repeated the affectiveinspiration Raphael, Rubens and Rembrandt drew from

pose of the Virgin of humility, which also served Moretto as

the engravings is well known.

a point of reference for his Madonna and Child with saints As

in these and other examples attest, the engravings,

the National Gallery, London, of 1540. We may not withbe

the possible exception of the Virgin of Humility, must

surprised that long after he had left Mantegna'shave shopbeen in circulation by about 1480.19 Indeed, if the

Francesco Caroto turned to the Entombment for one of the drawings in the Louvre (RF 28.918) and British Museum

predella scenes of his altar-piece in S. Giorgio in Braida,

(1854-6-28-62) copying motifs from the Entombment are by

Marco Zoppo - as has been argued - then we may say

Verona, but its direct translation by a Bolognese artist of

the generation of Francia into a painting with an extensive

with some confidence that Mantegna's prints had already

landscape background must be considered an exceptional begun their peregrinations by 1478, when Zoppo died.20

14P. HUMFREY: Cima da Conegliano, Cambridge [1983], pp.117, 127, 139, 159, Archivio Storico Lombardo, 5-6 [1966-67], pp.131-33.

notes three further possible references by Cima to this print as well as one to '8"The sea monsters originated from the workshop of Severo da Ravenna as a

Mantegna's engraving of the Entombment. popular variant of his statuette of Nepture on a sea-monster, the finest version of

'See G. PACCAGNINI: Andrea Mantegna, exh.cat., Mantua [1961], p.195; LEVEN- which is in the Frick Art Museum, New York. The 1542 inventory of Isabella

SON, OBERHUBER and SHEEHAN, op.cit. at note 6 above, p.170; and S. BANDERA d'Este's collection cites one such statuette of Neptune. For the plaque, see

BISTOLETTI: 'La Piet& di Agostino de'Fonduli in S. Satiro nell'occasione del suo PLANISCIG, op.cit. at note 16 above, p.292. The enamelled roundel in the Metro-

restauro', Arte lombarda, 86-7 [1988], pp.71-82. Paccagnini also reproduces a politan, probably from a glass flask, is unpublished. It is worth noting that a

polychrome wood relief repeating Mantegna's composition. number of prints after Mantegna's designs, above all those of the Triumphs,

'6L. PLANIsCIG: Andrea Riccio, Vienna [1927], pp.288-92, masterfully analyses the enjoyed equal celebrity.

features of the plaquette, which combines quotations from Mantegna's two '9David Landau's assertion in the catalogue (pp.53-54), that Mantegna's prints

prints with others from a well-known bronze plaque in the Kunsthistorisches were hard to come by seems contradicted by their widespread circulation.

Museum, Vienna (for which see note 39 below). For the bronze statuette and Diirer surely made copies after Mantegna's engravings, as he did after other

Paschal Candlestick, see ibid., pp.263-72. Italian prints, in an effort to master the elements of renaissance style, not

17See E. ARSLAN: 'La scultura nella seconda meta del quattrocento', in Storia di because he could not afford them.

Milano, Milan [1956], VI, p.713. Giovanni Agosti kindly reminds me that the 20The British Museum sheet was first ascribed to Zoppo by Popham and

frieze on the Palazzo Landi, Piacenza is also pertinent. It can be dated by Pouncey and is accepted as his work in both E. RUHMER: Marco Zoppo, Vicenza

documents to 1484: see G. FIORI: 'Le sconosciute opere piacentine di Guiniforte [1966], p.76, and L. ARMSTRONG: The Paintings and Drawings of Marco Zoppo, New

Solari e di Gian Pietro da Rho: I Portali di S. Francesco e del palazzo Landi', York [1976], p.416. The Louvre drawing is discussed only by Riihmer, p.72.

606

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER

A dating in the 1470s would make the 1476 notice of

Mantegna's temporary possession of a model book with

drawings whose subjects were directly relevant to his own

antique-inspired engravings particularly meaningful. No

less so is the demonstrated dependence of the figure of

Neptune in the Battle of the sea gods on the Felix gem,

acquired by Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga after the death

of Pope Paul II in 1471.21 This dating would also lend

further credibility to the postulated connexion of the Risen

Christ between Longinus and St Andrew to the foundation of

Alberti's church of S. Andrea, Mantua, in 1472 - the en-

graving at once commemorating that event and raising

the humble pilgrim's print to an object suitable for culti-

vated, Albertian tastes.22 The association of the print with

Mantua's most famous church would also explain how it

was that the figure of the risen Christ in the engraving

came to serve as the compositional model for one of the

frescoed roundels in the portico of S. Andrea (the tondo of

the facade contains the now illegible frescoes of St Andrew

and Longinus, dated 1488). And, of course, a dating of

the engravings prior to 1480 gives even greater resonance

to the well-known and variously interpreted letter of the

painter-engraver Simone da Reggio to Ludovico Gonzaga

in 1475 relating to some plates he was remaking for the

Mantuan painter Zoan Andrea.

Whatever precise meaning we may attach to Mantegna's

violent reaction to Simone's activity, it is clear that by

1475 prints were being made in Mantua, and that they

were being made by someone who described himself as

4. Bacchanal with a wine vat (detail), by Andrea Mantegna. H.4, engraving,

'pictore e taliatore de bolino' and 29.9

whom

by 43.7 cm. (TheLudovico,

Metropolitan Museum of Art,inNew hisYork).

letter of safe conduct, described more simply as a 'pictore':

in other words, by a painter-engraver such as Mantegna

himself was later reputed to be.23One We of themay

main issues

alsoraisedbetter

in the catalogue to the

appreciate Mantegna's expressionexhibition

of relief was the question

thatofhe authorship:

stillthat is, who

had the plates ('le stampe') at hand to

actually cut replace an image

these seven engravings (that they were designed

given as a present by Francesco Gonzaga by Mantegnain has never been doubted). Suzanne Boorsch's

1491.24

The success of the engravings was provocative

immediate.thesis that Mantegna

Not employed

only a professional

did they acquire an unparalleled status printmaker toamong artists

engrave his designs - an ideaas

first raised by

paradigms of the new humanist style Erica Tietze-Conrat

Mantegna in 194327

had - has thus far elicited sur-

forged

in Padua and refined in Mantua, they prisingly little response

were much among reviewers, as though the

sought

after by amateurs, a fact demonstrated question were

by either

theof little importance or were best left

imitations

and copies obviously created in response to print specialists.28

to this Yet,demand.

the central position of these

In every sense of the word these engravings engravings in the history of printmaking makes the issue

are landmarks

in the history of printmaking, andfar itfrom

is academic.

hardly Nor surprising

does it seem to me that one has to

that six of those currently assigned to Mantegna be a specialist to appreciate thatarethe technical innovations

mentioned in the 1550 edition of Vasari's Vite25 and five and experimental character of the prints presuppose an

in Scardeone's 1560 biography of Mantegna;26 nor that artist of the first order. Nothing could be further from

Baccio Baldini's workmanlike translation of Botticelli's

Vasari should also have ascribed the invention of engraving

to Mantegna. designs for the Divina Commedia.

21 See M. VICKERS: 'The Felix Gem in Oxford and Mantegna's Triumphal Pro-ascribed to him. It is assumed that the Entombment he mentions is the

tentatively

gramme', Gazette des Beaux-Arts, CI [1983], pp.97-102; and C. BROWN: horizontal

'Cardinalversion and not the vertical one (no.29) based on Mantegna's design.

26SCARDEONE

Francesco Gonzaga's collection of Antique Intaglios and Cameos: Questions of (De Antiquitate Patavii, Basel [1560], reprinted in KRISTELLER,

provenance, identification and dispersal', Gazette des Beaux-Arts, CI [1983],

op.cit. at note 24 above, pp.502-03) does not mention the Risen Christ, but he

pp.102-04. includes the Deposition from the Cross as well as the Triumphs, '& alia permulta'. He

22See LEVENSON, OBERHUBER and SHEEHAN, op.cit. at note 6 above, pp.178-80. then declares that although these prints were held in highest esteem but hard to

E. LINCOLN: 'Mantegna's Culture of Line', Art History, 16 [1993], pp.53-54, come by in his day, he owned nine, each different.

relates the print to the celebration of the Feast of the Blood in Mantua but goes 27E. TIETZE-CONRAT: 'Was Mantegna an Engraver?', Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 6th

on to make the implausible suggestion that the di sotto in si" viewpoint somehow ser., XXIV [1943], pp.375-81.

relates to the high placement of the two vases containing the relics. Much more 28An exception to this are the reviews of ROSAND, EMISON and STEDMAN-SHEARD,

interesting is her reminder that the first book printed in Mantua in 1472, an cited at note 5 above. Stedman-Sheard more or less follows Boorsch, as, appar-

edition of the Decameron, was intended to help offset the costs of S. Andrea. ently, does LINCOLN (loc.cit. at note 22 above, pp.37, 43, 49-52), who seems to me

23See the Appendix below. to accept too readily a tidy division between craftsman and painter while at the

24The relevant letters are in P.O. KRISTELLER: Andrea Mantegna, Berlin [1902], same time not sufficiently recognising that before the technical and stylistic

pp.550-51, docs.l112-14. innovations of Mantegna's engravings could be imitated, they had to be created

25Vasari also mentions the Deposition from the Cross, an engraving which is - obviously by an artist of the highest order. I wrongly underplayed the issue in

certainly based on a design of Mantegna's and in the catalogue (no.32) was my own catalogue essay, p.75.

607

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER

features more evident than in what seems to be the earliest

of the prints, the Entombment. The subsequent prints show

an increasing understanding of the inherent properties of

the medium, sacrificing tonal subtlety to greater formal

clarity. Yet only in the Virgin of humility- now usually

thought to be the latest of the prints - can one speak of a

distinction between the graphic style of the engravings

and the finest of the highly finished drawings attributable

to Mantegna.

It is indicative of the exceptional status of the engravings

that a comparison of the Battle of the sea gods to the related

drawing at Chatsworth (no.81) - often accepted as a

preparatory study - reveals the engraving to be superior

(compare, for example, the exaggeratedly wizened features

of the figure of the hag or the somewhat tentative relation-

ship of the legs, neck and head of the frontally viewed sea

horse in the drawing to their counterparts in the en-

graving).30 Even with the exquisite, if faded and foxed,

drawing of the Risen Christ with Longinus and St Andrew

(no.44), which David Ekserdjian convincingly argues in

the catalogue is by Mantegna, the engraving introduces

further, minute refinements, particularly in the drapery of

Christ, and is in many respects the stronger work of art.

In none of the engravings is there a sacrifice of overall

effect to detailed presentation or a misunderstanding of

spatial relationships. By contrast, in the engravings ascribed

with greater or lesser plausibility to the anonymous 'Premier

Engraver' (about whose consistency as a personality I

have strong reservations), one finds all the hallmarks of

the copyist: deadeningly regular contours, generalised

modelling that flattens rather than models the forms, a

5. Virgin and Child enthroned with an angel, by Andrea coarsening of expression,

Mantegna. and a frequent misunderstanding

Pen and light-

brown ink on paper, 19.7 by 14 cm. (The British ofMuseum,

the relationship

London).of one part of anatomy to another (the

awkward relationship of the head, arm and drapery in the

Hercules and Antaeus - technically one of the master's finest

The burin is handled with the dexterity engravings and

- is afreedom

case in point).ofIt is, to my mind, incon-

a pen rather than the steady regularity ceivable thatassociated with

the artist who created the Silenus with a group

the engraver's tool:29 instead of the of sharp, evenly

children (no.84), in whichincised

the heavy, uninflected contours

furrows of a professional goldsmith/engraver, and banal modelling the betray

lines theare copyist's hand, could

wonderfully varied in thickness, the havefacial and anatomical

been responsible for the Bacchanals. The Virgin and

features described with an almost gestural quality,

Child in the grotto (no.21) iswhile

no less deficient, and if we apply

modelling is achieved through a subtle to this hatching

heterogeneous that

corpusboth

the same critical standards

throws the forms into relief and confers on them a tonal we do to the variously attributed drawings, their status as

unity (see Figs.1, 2 and 4). As in Mantegna's most highlythe products of one or more talented technicians will

finished drawings, such as the Man lying on a stone slabbecome clear. In this respect, the comments of Kristeller

(no.43) or the Virgin and Child enthroned with an angel (Fig.5),

and Hind still carry complete conviction.3'

repeated strokes of the burin are used in an unorthodox In the catalogue it is argued that the production of the

way to create those dark contours by which Mantegna engravings involved the use of a detailed drawing or cartoon

habitually set off his figures, either drawn or painted (whatthat was transposed to the copper plate in successive sittings

Alberti would have called circonscrizione). or sessions by means of tracing paper (carta lucida). Super-

The lines have the richness generally associated with ficially, this seems a plausible thesis, and the production of

the presence of a burr, but whether there is any true use aofsheet of carta lucida according to the recipe found in

drypoint seems to me a moot point. Nowhere are these

Cennino Cennini reveals just how efficient this system

2' . . a clear outline is supported by shading in open parallels and lighter connexion between his highly worked-up drawings and the style of his engravings.

return strokes laid obliquely between the parallel lines. The return stroke would

She then goes on to use as a point of departure for her discussion the drawings of

be natural to a draughtsman but not to an engraver, so that its use in engraving

St James led to execution and the studies of Christ at the column, which are compo-

shows a direct imitation of a draughtsman's manner. The seven platessitional

of sketches whose function is far removed from that of the more highly

undoubted authenticity, and a few of the remainder, show an even more

finished drawings and the engravings.

methodical use of the return stroke than most of the Florentine engravings,

3"The attribution of the drawing to Mantegna is defended by GOLDNER, 0loc.Cit.

and their scheme closely follows the linear system of Mantegna's own pen

at note 5 above.

drawings. . .': HIND, op.cit. at note 4 above, p.4. Curiously, LINCOLN (loc.cit. at note

31 HIND, op.cit. at note 4 above, p.5; KRISTELLER, op.cit. at note 24 above, pp.387-

22 above, pp.44-45) while accepting the notion that Mantegna's engravings 88.

are

meant in some way to simulate his drawings, denies that there is a demonstrable

608

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER

6. Tracing of the drawing of the Risen Christ between St Andrew and Longinus in the Staatliche

superimposed over the related engraving by Andrea Mantegna in the Metropolitan Museum

would have been.32 However, the matter

(evidently can only

slightly out be

of register).

tested in one instance, and that is the drawing in Munich

itioning of the head of Christ does

of the Risen Christ between Longinus and St Andrew.

significantly fromAtthe

thedrawing. Yet

close of the exhibition I examined this drawing

which underwas

the drawing the manifestl

microscope and in good light, and being excised and glued it

made a tracing of down onto

(Fig.6). It should be stated at the on

outset that the

the sheet. drawing

This readjustment comp

is of the highest quality: nowhere are thepoint

sit viewing contours orthe most in

that is

internal hatching mechanical. The hand

design. of St

Were theAndrew

head to be re-po

holding the cross is of a marvellous subtlety,

conceived, and

the the facial

drawing would confor

features are described with consummate mastery.

print, and we Theto conclude

are bound

quality of the drawing is crucial

wasto an appraisal

done by a later of its

owner of the

status, for the tracing of it revealed that in

understand all but one

Mantegna's intention. O

respect it conforms to the engraving.

drawingThere is no sign

is either of

the cartoon from

the sorts of adjustment of design posited

made or in the catalogue

is based on a mechanical

on the misleading basis of superimposed

graving. Thetransparencies

quality of the drawi

tracing

32A sheet of carta lucida was kindly made for me paperJennings.

by Jeffrey and received ink

Apart readily.

from

a rather unpleasant fishy smell, the sample had all the properties of transparent

609

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER

second thesis. By the same token, small - almost insignifi-

cant - variations of internal modelling argue strongly that

the engraving is a further, clarifying stage in the creative

process rather than a craftsman-like copy.33 These two

works provide the best gauge for understanding the relation-

ship between the various prints and their putative designs

by Mantegna.

What of the four engravings newly attributed to Man-

tegna by David Landau (nos.29, 32, 36, 67)? One of

them, the Descent from the Cross, was included by Vasari

and Scardeone among the engravings by Mantegna, and

another, the vertical Entombment, enjoyed a fame among

artists in the late fifteenth century almost as great as its

horizontal counterpart.34 The other two, the Flagellation

and the Descent into Limbo, are noble compositions, but

Hind recognised that they differ technically from the seven

key works, conforming to more conventional practice.35

We may, moreover, note those hallmarks of the copyist

mentioned above. In the Descent into Limbo, the tunnel-like

entrance to the underworld is treated in a perfunctory

fashion, obliterating any sense of depth (how are we to

understand that curiously abrupt shading at the right of

the cave opening?); the tail of the central demon is reduced

to a flat pattern; and Eve appears to have inadvertently

stepped on the foot of her companion. All of these awk-

wardnesses are resolved in the pen drawing in the Ecole

des Beaux-Arts, Paris (no.66) and the painting at Bristol

(no.69), and regardless of what one makes of those two

works, they surely argue against Mantegna having executed

the engraving.36 Similarly, in the Flagellation of Christ the

placement of the background figures on the squared pave-

ment is contradicted by their diminutive scale, and the

column at the right has no base but hangs suspended in

the air (this omission is hardly due to the unfinished state

of the engraving, since the squaring of the pavement is

complete in this section). This is simply inconceivable in a

work by Mantegna. (Even Giovan Antonio da Brescia, in

his copy of the engraving, realised that this omission was

unacceptable.)

The vertical Entombment and the Descent from the Cross

are superior as works of art, but far more conventional in

the handling of the burin when compared to the seven by

Mantegna, and there is, again, a notable flattening of

forms, as if the engraver had somehow lost sight of the

overall effect in his effort carefully (and somewhat mech-

7. Nudeputto, after a model by Andrea Mantegna. Bronze, with silvered eyes,

anically) to reproduce the details of his compositions. 20.5 cm. high. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

This is particularly evident in the left-hand seated woman

33Ekserdjian's attribution of the Munich drawing is accepted by both HIRST presentation drawing, such as those inJacopo Bellini's albums. Its draughtsman-

(loc.cit. at note 5 above, p.321: 'only severe fading of the sheet prevents unequivocal ship is not, therefore, strictly comparable to either pen and ink sketches or to a

endorsement'), and GOLDNER, loc.cit. at note 5 above. cartoon. What seems to me to weigh in its favour is the consistency and

34See the derivations I cite in the catalogue, p.42 note 16. The composition of economy with which the conception is realised - a consistency found in neither

the Entombment is reproduced on a maiolica plaque dated 1523 (Victoria and the print nor the painting and, I believe, uncharacteristic of a copy as well. A

Albert Museum, no.278). Much the most slavish use of the Deposition is in a fresco single viewing point is adopted for the whole scene, with the audaciously

in the ex-convent of the Poor Clares in Martinengo (Bergamo), for which see foreshortened demons viewed from below and the plateau from above (this

F. MAZZINI: Affreschi lombardi del Quattrocento, Milan [1965], pp.472-73, ills.231- effect is greatly compromised in both the print and the painting). The space of

33. Just how popular the composition of this print became may be judged by the plateau on which the action takes place is articulated with consummate

the fact that it is reproduced in a bronze plaquette (see, for example, E. MOLINIER: mastery, particularly obvious at the left, where the rise of the ledge has been

Les Plaquettes, Paris [1886], II, p.36). thought out with Mantegna's scrupulous care and the relation of the obliquely

35 Op.cit. at note 4 above, p.5. held cross and foreshortened piece of lumber effectively measure the depth of

36HIRST and GOLDNER (both cited at note 5 above) dismiss the Ecole des Beaux- Christ's stance. The details of the splintered door are treated with a concision

Arts drawing out of hand. 'Journeyman level' is how Hirst characterises it, a and logic found in neither the print nor the painting. I think it would be hard to

surprising judgement in view of James Byam Shaw's ascription of it to Bellini argue that the handling of the interior of the opening of the cave is by a minor

and Giles Robertson's cogent arguments in favour of Mantegna. It is on vellum, master or copyist; the scaly arm of the left hand demon is no less masterfully

and although in part unfinished, it has the character we might associate with a described.

610

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER

in the Entombment and in the three standing

doubted thatfigures to the

the remarkable foundry

left of the cross in the Descent from the opportunities

ample Cross, where the for an artist inte

shoulders, arms, and heads lie on the

ing. same

This plane.

aspect But

of Mantegna's work w

perhaps most indicative is the way the the lights and

exhibition exceptdarks by Anthony Ra

have been so evenly distributed that the spatial

entry for theeffect bronze is bust of Manteg

greatly compromised. If the landscapeto haveand beenfigure castgroups

by Mantegna (a plas

of the vertical Entombment are compared to those in the

in the exhibition), and in a passing

horizontal Entombment, where tone and value

Landau.39 At are Newused to

York, a bronze st

define space and not simply to model form,

the same the distinction

pose (although reversed) as the infant on the

will be apparent. Moreover, the engraved line

extreme left of is strangely

the Bacchanal with a wine vat was added to

uninflected. Rather than transmitting the graphology

the exhibition of a that Mantegna

(Fig.7). Lomazzo records

drawn composition, the print gives the

used effect

modelled of

figurines to a careful

stage his compositions, and the

rendition of the minutely described forms

model ofputto,

of this bronze a painting.

of which the finest cast is in the

That many of the engravings associated with

Museum of Fine Mantegna

Arts, Houston, may well have been by

replicate paintings - even muralsMantegna

- hashimself.

frequently

A genericallybeen

Mantegnesque drawing

asserted, but it can really be sustained only in

in the Fondazione the

Horne case

(5858) of the figure from

studying

these two, in which an attempt seems to have

two different angles been

would seemmadeto certify the genesis of

to transcribe the terms of Mantegna's painted

the statuette and thecompositions

uses to which it was put.40 It seems

into black and white. It follows reasonable

that the drawings

that, like Pisanello before at

him, Mantegna should

Brescia, the British Museum andhave the Courtauld

turned to this medium -(nos.27,

which, like engraving, offered

26 and 35) that are related to the themes of these

the possibility engravings

of replication (something that had been a

are more likely to be studies for paintings.

concern of37

Donatello and was to fascinate other renaissance

In her essay Boorsch makes much of

artists theIf difficulty

as well). of that he also

it could be demonstrated

engraving and the improbability ofchased

an his own bronze

artist of statuettes,

Mantegna's then there would be no

stature taking the trouble to master

reasonthis time-consuming

to be surprised at his proficiency with the burin. It

and secondary medium. However, is, inthese

any event,concerns seem

indicative of his experimentation in other

not to have bothered sixteenth-century writers,

media that the bronze and

statuette, of whichitfour casts exist, is

should not be forgotten that among virtuallyScardeone's

contemporary with the sources

engravings.41 (Mantegna's

was a letter written by Girolamo Campagnola, a friend

bronze portrait is usually dated to theof1480s on the basis

Mantegna who sent his painter/engraver

of the apparent age son Giulio to

of the artist.)

Mantua in 1497 to work with the great man.

Of all the Butofbeyond

great artists the early renaissance, Mantegna

this circumstantial evidence, we know

was the that Mantegna

most self-possessed, had

and there is no reason to be

a keen interest in media other than painting.

surprised In Padua

that he should have seizedheon the medium of

had first-hand acquaintance with modelling in terracotta,

engraving to advertise his artistic stature. Indeed, when

the medium of the altar-piece in the Ovetari

we consider Chapel

his humanist that

friends and their use of the

Mantegna had made a bid to carry printing

out but presswhich,

to spread theirin fame

1449,- men such as Filippo

was assigned to his erstwhile partner Niccol6

Nuvolone, Pizzolo.38

whose speech delivered on His

the occasion of King

Christian

first project in Mantua had been the of Denmark'sof

designing arrival in Mantua in 1474 was

a chapel

for Ludovico, to which a drawing of a paschal

printed candlestick

that same year, or Felice Feliciano, who in 1475

(no.27v) may be related, and in 1483 he designed

collaborated vases

with the printer to of Ferrara and the

Severino

be made in silver. Nothing seems to haveyear

following come ofown

set up his his de-

press at Poiano in partnership

signs for the tomb of Barbara of Brandenburg

with Innocente Zileto42 and, later,

- it seems only natural that

for a statue of Virgil for IsabellaMantegna

d'Esteshould

beyond prelimi-

have appropriated engraving not only

nary drawings, but Giovanni Santi as a states

means of that Mantegna

reproducing his designs but as a way of

practised sculpture as well as painting, and

transmitting it cannot

his drawing style: asbe

an exemplum of his

37GOLDNER, loc.cit. at note 5 above, has reasonably queried whether the fore- Drawings, and their relation to the Engravings of Mantegna's School', Old

shortened figures on the recto of cat.26 have any necessary relation to the theme Master Drawings, IX [1936-37], p.59.

at all. GENTILI (loc.cit. at note 5 above, p.62) reasonably associates the engravings 4 The four casts are in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Metropolitan

with an extensive Passion series of which three paintings in the National Gallery, Museum of Art, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, and the Museo Nazionale

London, record further compositions. di Capodimonte, Naples. The Naples cast is from the Farnese collection.

38The attribution of this remarkable work is still uncertain. Recently, G. GENTILINI

J. MONTAGU (review in THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE, CVIII [1966], p.46) rightly

('Sulle prime tavole d'altare in terracotta dipinta e invetriata', Arte Cristiana,

emphasises the 'Mantegnesque pose and bodily structure' of the bronze and

LXXX [1992], pp.444-45, and 450 note 38) has urged considering Mantegnarejects both Pope-Hennessy's assertion that the statuette was Florentine and

as the author of the predella of the Adoration of the Magi. This idea has much to

recommend it.

Planiscig's contention that there was an antique prototype. For a recent summary

of the literature see D.A. COVI, in Italian Renaissance Sculpture in the Time of

39Landau's comment (p.48) concerns a bronze plaque of the Entombment in the

Donatello, exh.cat., Detroit and Fort Worth [1986], pp.211-12. Covi inexplicably

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (inv.no.Pl.6059), a work with a probable missed the fact that the related figure in the Bacchanal with a wine vat is virtually a

provenance from Mantua but more likely of Paduan than Mantuan origin: see mirror image, and the drawing in the Fondazione Horne a study based directly

M. LEITHE-JASPER: Renaissance Master Bronzesfrom the Collection of the Kunsthistorisches

on the statuette. If the similarities already noted by Montagu with Francesco

Museum Vienna, exh.cat., Washington, Los Angeles and Chicago [1986], pp.61- del Cossa's decorations in the Palazzo Schifanoia are accepted, then the model

64. See also the analysis in PLANISCIG, op.cit. at note 16 above, pp.290-92. The for the statuettes must pre-date 1470.

Vienna plaque was exhibited at New York alongside Mantegna's engraving, 42For Nuvolone's oration, see D. RHODEs: Studies in Early Italian Printing, London

and I do not think there could have been a clearer demonstration of its very [1982], p.147; for Feliciano, see C. MITCHELL: 'Felice Feliciano Antiquarius',

different, Donatellesque approach to narration. Proceedings of the British Academy, 47 [1961], pp.201-02.

40This connexion is recognised in j. BYAM SHAW: 'A Group of Mantegnesque

611

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MANTEGNA AS A PRINTMAKER " SIGNORELLI AND RAPHAEL

contact in Mantua was not Mantegna but Zoan Andrea, and that after havin

ingenio.43 Nor does there seem to me to exist a real basis for

paid the obligatory visit to Mantegna he turned to his old friend, who required

denying his insistence on wielding the burin

his assistance. himself.

Zoan, it seems, He

had owned some engraved plates ('stanpe') that had

was, after all, intolerant of mediocrity, whether

been stolen together intellectual

with drawings and medals. Simone offered to remake th

engravings. The fact that Simone offered to 'refarge le dite stanpe' makes it virtually

or technical. It is, indeed, difficult to believe that anyone

certain that plates, not prints were involved; it also indicates that Zoan was not

other than Mantegna could haveable

pushed the

to recut the plates recalcitrant

himself. (Had Simone made the first, stolen set that h

medium of copper-plate engraving into the

now offered 'remake'?)directions

This action so enraged he

Mantegna that he took violen

measures to forestall their production. There is an implication that Zoan

did, and although he was hardly the inventor of engraving,

activity - twice halted - somehow trespassed on Mantegna's interests, althoug

he may legitimately claim to have been

whether its

this was greatest

because Italian

Zoan was attempting to turn a profit by pirating

practitioner - the first in a long linedesigns,

Mantegna's of those painter-

as both Kristeller and Hind maintained, or becaus

Mantegna simply would not abide independent artistic activity in Mantu

engravers who redefined the making of prints.

cannot be said. There is no basis for the suggestion of Landau that Zoan Andre

had stolen some of Mantegna's own plates and that it was these Simone se

The Metropolitan Museum about

ofArt,

to copy.New

Nor can York

LIGHTBOWN's assertion that 'Mantegna was anxious to

recruit [Simone] to engrave his own designs and that he was furious when a

enemy succeeded in capturing his services' (Mantegna, Oxford [1986], p.237 be

sustained. All that Simone ever received from Mantegna during his four-month

43The analogy of Mantegna's engravings withstay

printing

were vague is effectively

promises of work and aargued by

show of friendship. The crucial point is

LINCOLN, op.cit. at note 22 above, pp.52-55.

that She also 1475

even before notes the analogy

printmaking to

was a going concern in Mantua in which

Pisanello's medals. Mantegna had a vested interest. It is also worth noting that Simone settled in

Verona to complete the plates, suggesting that prints by Simone do exist. No

without reason KRISTELLER (Andrea Mantegna, London [1901], p.391; very tenta-

tively followed by Hind) suggested that these were likely to be the four engraving

Appendix: Simone da Reggio's letter to Ludovico Gonzaga of 1475.Landau has attempted to reascribe to Mantegna - works Boorsch has, instead

included in her expanded list of engravings by the anonymous Premier Engraver

(for which, see below). Note should be made of JACOBSEN'S tentative suggestion

Simone's letter (printed in KRISTELLER, see note 24 above) has been used to bolster

so many conflicting views of Mantegna's involvement with printmakink that (loc.cit.

it at note 10 above, p.627, note 24) that Simone's letter may refer to a con-

tact

may be well to examine exactly what it does say. It establishes that Simone's mainwith Mantegna going back to the early 1460s.

TOM HENRY

Signorelli, Raphael and a 'mysterious' pri

in Oxford

ONE element on a drawing in the Ashmolean Museum, model posed in the manner of Michelangelo's David).2

The sheet is generally considered to date from early in

Oxford, has repeatedly been described as 'mysterious'.'

Raphael's

The recto of the sheet (Fig.9), a pen and ink study of a so-called Florentine period (c.1505-07), a date

group of four standing warriors, has been unanimouslyderived from the style of the group on the recto. The other

('mysterious') element on the sheet, inked-in on the verso

attributed to Raphael, and most critics have commented

on the relationship of the central figure to Dqnatello's also visible on the recto, is a pricked profile of a head.

but

St George from Orsanmichele, Florence (now in the MuseoThis pricked design was first discussed in the nineteenth

century by Sir Charles Robinson. Both he, and then Carl

Nazionale di Bargello). The verso (Fig.8) has other studies

Ruland, noticed the head and concluded that the figure

in pen and ink - two side views of a nude male .torso, one

concentrating on the right arm, and one of a knee- and a female.3 In 1919 Oskar Fischel proposed a connexion

was

standing male nude drawn in black chalk. These studies with Luca Signorelli's frescoes at Orvieto, suggesting that

have not been accepted as Raphael with the same enthusi-the pricked design 'reminds one of some of the profiles by

asm, but have found champions who consider them to be Signorelli in the Resurrection of the flesh' (Fig. 10).4 Sub-

youthful studies of a nude figure (the two torsos after sequently,

a in 1956, Karl Parker suggested a more precise

discussion (with an updated bibliography) is C.B. CAPPEL: 'A Substitute Cartoon

*This article would not have been possible without the assistance of Patricia

Robertson, Giusi Testa of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Ambientali Artisticifor Raphael's "Disputa"', Master Drawings, XXX [1992], pp.9-30.

Architettonici, e Storici di Umbria, the restorers of the Cooperativa C.B.C.2The

di studies on the verso were rejected by FISCHEL and PARKER (both loc.cit.

Roma, Catherine Whistler, Judith Chantry, Mira Hudson, Fabrizio Mancinelli above), but accepted implicitly by J.D. PASSAVANT (Raphael d'Urbin et son pare

and Arnold Nesselrath. Dugald McClellan kindly sent me a copy of his unpub- Giovanni Santi, Paris [1860], II, p.510, no.541) and by GERE and TURNER (0loc.Cit.

above, with a comparison to their no.38 on pp.60-61). A. FORLANI TEMPESTI

lished doctoral thesis (Melbourne University, 1992) which was otherwise unob-

(Raffaello: L'Opera, Le Fonti, La Fortuna, Novara [1968], II, p.337) was the first

tainable. I also appreciated the opportunities to discuss my findings with Claire

Van Cleave, Laurence B. Kanter and Michael Hirst. to propose the relationship to Michelangelo's David.

3j.c.

' See O. FISCHEL: Raffaels Zeichnungen, Berlin [1913-41] (cited in these notes asROBINSON: A Critical Account of the Drawings by Michael Angelo and Raffaello in

the University Galleries, Oxford, Oxford [1870], p.168, no.46; C. RULAND: The

FISCHEL), II, p.113, no.87; and K.T. PARKER: Catalogue of the Collection of Drawings

in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford [1956] (cited in these notes as PARKER), II,

Works of Raphael Santi da Urbino . . . in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle .

privately printed [1876], p.319, nos.xliii (recto) and xliv (verso).

pp.271-72, no.523. Together with j. GERE and N. TURNER (Drawings by Raphael

4Loc.cit. at note 1 above: 'Er erinnert an einige Profile Signorellis in der Auferstehung

from the Royal Library, the Ashmolean, the British Museum, Chatsworth and other English

Collections, exh.cat., British Museum, London [1983], p.67, no.46), both these der Seligen'.

scholars describe the pricking discussed below as 'mysterious'. The most recent

612

This content downloaded from

84.204.8.138 on Wed, 14 Sep 2022 09:16:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Mantegna or Pollaiuolo?Document5 pagesMantegna or Pollaiuolo?Lubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Annibale Carracci's Visual WitDocument7 pagesAnnibale Carracci's Visual WitМарија РистићNo ratings yet

- Burlington Magazine Publications LTDDocument5 pagesBurlington Magazine Publications LTDTiziano LicataNo ratings yet

- Jacobsen, The Meaning of Mantegna's Battle of Sea MonstersDocument8 pagesJacobsen, The Meaning of Mantegna's Battle of Sea MonstersClaudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- Tenebrism in Baroque Painting and Its Ideological BackgrowndDocument23 pagesTenebrism in Baroque Painting and Its Ideological BackgrowndAlexandra ChevalierNo ratings yet

- Andrea Mantegna and the Italian RenaissanceFrom EverandAndrea Mantegna and the Italian RenaissanceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- CARPO How Imitate 2001Document12 pagesCARPO How Imitate 2001Marina BorgesNo ratings yet

- Masaniello's Revolt in Seventeenth-Century Naples PaintingsDocument17 pagesMasaniello's Revolt in Seventeenth-Century Naples PaintingsAlbaAlvarezDomequeNo ratings yet

- Robert Rosenblum - The Origin of Painting A Problem in The Iconography of Romantic ClassicismDocument17 pagesRobert Rosenblum - The Origin of Painting A Problem in The Iconography of Romantic Classicismlaura mercaderNo ratings yet

- A Trick of the Eye Trompe Loeil MasterpiDocument2 pagesA Trick of the Eye Trompe Loeil MasterpierjauraNo ratings yet

- A Forgotten Chapter in The Early History of Quadratura Painting. The Fratelli RosaDocument13 pagesA Forgotten Chapter in The Early History of Quadratura Painting. The Fratelli RosaClaudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- Baroque Painting's Tenebrism Technique and Its Ideological InfluencesDocument23 pagesBaroque Painting's Tenebrism Technique and Its Ideological InfluencesJuan Carlos Montero VallejoNo ratings yet

- College Art AssociationDocument4 pagesCollege Art AssociationCallsmetNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 01, No. 02, December, 1857 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsFrom EverandThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 01, No. 02, December, 1857 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Prints and Visual C 009941 MBPDocument302 pagesPrints and Visual C 009941 MBPnaluahNo ratings yet

- A Concise History of Modern PaintingDocument378 pagesA Concise History of Modern PaintingSimone Ferreira100% (1)

- The Fruit Vendor by CaravaggioDocument7 pagesThe Fruit Vendor by CaravaggionnazolgacNo ratings yet

- Renaissance in Italy: The Fine ArtsDocument214 pagesRenaissance in Italy: The Fine ArtsGutenberg.org100% (2)

- Role of the Mænad in 15th-16th Century Florentine ArtDocument6 pagesRole of the Mænad in 15th-16th Century Florentine ArtMiguel Ángel Rego RoblesNo ratings yet

- Paul GrendlerDocument2 pagesPaul GrendlerMarijana NikolicNo ratings yet

- PAOLETTI, John T. Michelangelo's Masks.Document19 pagesPAOLETTI, John T. Michelangelo's Masks.Renato MenezesNo ratings yet

- Illuminated Manuscripts 120 illustrationsFrom EverandIlluminated Manuscripts 120 illustrationsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Art History Reviewed X Francis Haskell PDocument4 pagesArt History Reviewed X Francis Haskell PAdna MuslijaNo ratings yet

- Landscape Drawing Pietro Da CortaDocument27 pagesLandscape Drawing Pietro Da CortaAgung PirsadaNo ratings yet

- Nordenfalk FiveSensesLate 1985Document32 pagesNordenfalk FiveSensesLate 1985Luba Lubomira NurseNo ratings yet

- Architecture and ekphrasis: Space, time and the embodied description of the pastFrom EverandArchitecture and ekphrasis: Space, time and the embodied description of the pastNo ratings yet

- Greene GameDocument4 pagesGreene GameExtraslimfilterNo ratings yet

- Southern Baroque Art - Painting-Architecture and Music in Italy and Spain of the 17th & 18th CenturiesFrom EverandSouthern Baroque Art - Painting-Architecture and Music in Italy and Spain of the 17th & 18th CenturiesNo ratings yet

- Some Observations On The Brancacci Chapel Frescoes After Their CleaningDocument18 pagesSome Observations On The Brancacci Chapel Frescoes After Their CleaningvolodeaTisNo ratings yet

- Donatello's Influence On Mantegna's Early Narrative ScenesDocument11 pagesDonatello's Influence On Mantegna's Early Narrative ScenesLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- The Venetian Painters of The RenaissanceThird Edition by Berenson, Bernard, 1865-1959Document119 pagesThe Venetian Painters of The RenaissanceThird Edition by Berenson, Bernard, 1865-1959Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- The Venetian Painters of The RenaissanceThird Edition by Berenson Bernard 1865 1959Document119 pagesThe Venetian Painters of The RenaissanceThird Edition by Berenson Bernard 1865 1959Ariel SpallettiNo ratings yet

- Toward A New Model of Renaissance AnachronismDocument14 pagesToward A New Model of Renaissance Anachronismρεζίν ντέιNo ratings yet

- The Paradox of Rembrandt's 'Anatomy of Dr. TulpDocument5 pagesThe Paradox of Rembrandt's 'Anatomy of Dr. TulpUn StableNo ratings yet

- Jacob Burckhardt - The CiceroneDocument356 pagesJacob Burckhardt - The CiceroneCydLosekann100% (3)

- The Metropolitan Museum Journal V 7 1973Document169 pagesThe Metropolitan Museum Journal V 7 1973Éva TarczaNo ratings yet

- Sebastiano - New DrawingDocument3 pagesSebastiano - New DrawingD ANo ratings yet

- Derbes A. - A Crusading Fresco Cycle at The Cathedral of Le PuyDocument17 pagesDerbes A. - A Crusading Fresco Cycle at The Cathedral of Le PuyIoannis VitaliotisNo ratings yet

- Timothy J Clark From Cubisam To Guernica - CompressDocument327 pagesTimothy J Clark From Cubisam To Guernica - Compresskailanysantos441No ratings yet

- S.J. Freedberg - Circa 1600 - A Revolution of Style in Italian Painting-Harvard University Press (1983)Document146 pagesS.J. Freedberg - Circa 1600 - A Revolution of Style in Italian Painting-Harvard University Press (1983)Pablo GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Michelangelo and The Reform of Art ComplDocument160 pagesMichelangelo and The Reform of Art ComplDiagoNo ratings yet

- Francesco Xanto Avelli and PetrarchDocument13 pagesFrancesco Xanto Avelli and PetrarchClaudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- CARABELL, Paula. Figura Serpentinata, Becoming Over Being in Michelangelo's Unfinished WorksDocument19 pagesCARABELL, Paula. Figura Serpentinata, Becoming Over Being in Michelangelo's Unfinished WorksRenato MenezesNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 188.252.255.208 On Tue, 07 Mar 2023 19:53:21 UTCDocument35 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 188.252.255.208 On Tue, 07 Mar 2023 19:53:21 UTCMarkoNo ratings yet

- The Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art - Carl NordenfalkDocument32 pagesThe Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art - Carl NordenfalkAntonietta BiagiNo ratings yet

- Divine Inspiration in Caravaggios Two St. MatthewsDocument24 pagesDivine Inspiration in Caravaggios Two St. MatthewsMaría Magdalena ZieglerNo ratings yet

- Pathosformel Pathos Formula Affective SoDocument10 pagesPathosformel Pathos Formula Affective SoLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- A Touching Image Andrea Mantegna S EngraDocument19 pagesA Touching Image Andrea Mantegna S EngraLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 188.170.82.94 On Sat, 24 Dec 2022 10:44:41 UTCDocument18 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 188.170.82.94 On Sat, 24 Dec 2022 10:44:41 UTCLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Artists Art in The Renaissance Full Book PDFDocument242 pagesArtists Art in The Renaissance Full Book PDFLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Icon To Narrative, The Rise of The Dramatic Close-Up in Fifteenth-Century Devotional Painting by Sixten Ringbom Review By: Colin EislerDocument4 pagesIcon To Narrative, The Rise of The Dramatic Close-Up in Fifteenth-Century Devotional Painting by Sixten Ringbom Review By: Colin EislerLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Despair and Hope Personified in Medieval ArtDocument13 pagesDespair and Hope Personified in Medieval ArtLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Antiquity and Its InterpretersDocument15 pagesAntiquity and Its InterpretersLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- A Closer Look at Mantegna's PrintsDocument40 pagesA Closer Look at Mantegna's PrintsLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Arcimboldo and Propertius. A Classical Source For Rudolf II As VertumnusDocument8 pagesArcimboldo and Propertius. A Classical Source For Rudolf II As VertumnusLubava Chistova100% (1)

- A Re-Evaluation of Two Mantegna PrintsDocument12 pagesA Re-Evaluation of Two Mantegna PrintsLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Donatello's Influence On Mantegna's Early Narrative ScenesDocument11 pagesDonatello's Influence On Mantegna's Early Narrative ScenesLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Beroaldus On Francia. Michael Baxandall and E. H. GombrichDocument5 pagesBeroaldus On Francia. Michael Baxandall and E. H. GombrichLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Allure of Ancient Rome PDFDocument28 pagesAllure of Ancient Rome PDFLubava Chistova100% (1)

- The Scandal of Metaphor Metaphorology and SemioticsDocument42 pagesThe Scandal of Metaphor Metaphorology and SemioticsLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- "Tanto Che Basti": La 'Notomia' Nelle Arti Figurative Di Età Barocca e Nel Pensiero Di Carlo Cesi e Carlo MarattiDocument12 pages"Tanto Che Basti": La 'Notomia' Nelle Arti Figurative Di Età Barocca e Nel Pensiero Di Carlo Cesi e Carlo MarattiLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- Shapes of Earth and Time in European GardensDocument8 pagesShapes of Earth and Time in European GardensLubava ChistovaNo ratings yet

- XXCCCDocument17 pagesXXCCCwendra adi pradanaNo ratings yet

- ChromosomesDocument24 pagesChromosomesapi-249102379No ratings yet

- How Do I Prepare For Public Administration For IAS by Myself Without Any Coaching? Which Books Should I Follow?Document3 pagesHow Do I Prepare For Public Administration For IAS by Myself Without Any Coaching? Which Books Should I Follow?saiviswanath0990100% (1)

- LNG Vaporizers Using Various Refrigerants As Intermediate FluidDocument15 pagesLNG Vaporizers Using Various Refrigerants As Intermediate FluidFrandhoni UtomoNo ratings yet

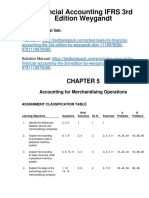

- Financial Accounting IFRS 3rd Edition Weygandt Solutions Manual 1Document8 pagesFinancial Accounting IFRS 3rd Edition Weygandt Solutions Manual 1jacob100% (34)

- Oas Community College: Republic of The Philippines Commission On Higher Education Oas, AlbayDocument22 pagesOas Community College: Republic of The Philippines Commission On Higher Education Oas, AlbayJaycel NepalNo ratings yet

- Masterbatch Buyers Guide PDFDocument8 pagesMasterbatch Buyers Guide PDFgurver55No ratings yet

- Quality Improvement Reading Material1Document10 pagesQuality Improvement Reading Material1Paul Christopher PinedaNo ratings yet

- Galambos 1986Document18 pagesGalambos 1986gcoNo ratings yet

- Marulaberry Kicad EbookDocument23 pagesMarulaberry Kicad EbookPhan HaNo ratings yet

- Eportfile 4Document6 pagesEportfile 4api-353164003No ratings yet

- PBS-P100 Facilities Standards GuideDocument327 pagesPBS-P100 Facilities Standards Guidecessna5538cNo ratings yet

- Visualization BenchmarkingDocument15 pagesVisualization BenchmarkingRanjith S100% (1)

- Plastic Welding: We Know HowDocument125 pagesPlastic Welding: We Know Howprabal rayNo ratings yet

- Document-SAP EWM For Fashion 1.0: 1.general IntroductionDocument3 pagesDocument-SAP EWM For Fashion 1.0: 1.general IntroductionAnonymous u3PhTjWZRNo ratings yet

- X RayDocument16 pagesX RayMedical Physics2124No ratings yet

- Jotrun TDSDocument4 pagesJotrun TDSBiju_PottayilNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behaviour Group Assignment-2Document4 pagesOrganizational Behaviour Group Assignment-2Prateek KurupNo ratings yet

- Rotational Equilibrium SimulationDocument3 pagesRotational Equilibrium SimulationCamille ManlongatNo ratings yet

- Basic LCI To High LCIDocument3 pagesBasic LCI To High LCIIonut VladNo ratings yet

- Sample QuestionsDocument70 pagesSample QuestionsBushra MaryamNo ratings yet

- Fermat points and the Euler circleDocument2 pagesFermat points and the Euler circleKen GamingNo ratings yet

- Bhakti Trader Ram Pal JiDocument232 pagesBhakti Trader Ram Pal JiplancosterNo ratings yet

- Cell Selection ReselectionDocument35 pagesCell Selection ReselectionThiaguNo ratings yet

- TILE FIXING GUIDEDocument1 pageTILE FIXING GUIDEStavros ApostolidisNo ratings yet

- Android TabletsDocument2 pagesAndroid TabletsMarcus McElhaneyNo ratings yet

- Hydrocarbon: Understanding HydrocarbonsDocument9 pagesHydrocarbon: Understanding HydrocarbonsBari ArouaNo ratings yet

- Hisar CFC - Approved DPRDocument126 pagesHisar CFC - Approved DPRSATYAM KUMARNo ratings yet

- Copy Resit APLC MiniAssignmentDocument5 pagesCopy Resit APLC MiniAssignmentChong yaoNo ratings yet

- GKInvest Market ReviewDocument66 pagesGKInvest Market ReviewjhonxracNo ratings yet