Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Property Law End Term

Uploaded by

Deepti UikeyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Property Law End Term

Uploaded by

Deepti UikeyCopyright:

Available Formats

NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, BHOPAL

SEMESTER IV

PROPERTY LAW

END TERM PROJECT

R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

[AIR 1970 SC 1872]

SUBMITTED TO

Prof. Dr. Sanjay Yadav

SUBMITTED BY

Srajan Tyagi

Page |1 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

(2019BALLB107)

Page |2 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

CERTIFICATE

“This is to certify that the case analysis – R. Khemraj v. Barton Sons and Co. has been prepared

and submitted by Srajan Tyagi who is currently pursuing their BALLB at National Law Institute

University, Bhopal in fulfilment of Constitutional Law I course. It is also certified that this is an

original case analysis and this has not been submitted to any other university, nor published in

any journal.”

Date-

Signature of the student-

Signature of Research Supervisor-

Page |3 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

“The project has been made possible by the unconditional support of many people. I would like

to acknowledge and extend my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Sanjay Yadav for guiding me

throughout the development of this paper into a coherent whole by providing helpful insights and

sharing her brilliant expertise. I would also like to thank the officials of the Gyan Mandir, NLIU

for helping us to find the appropriate research material for this study.”

I am deeply indebted to my parents, seniors and friends for all the moral support and

encouragement.

Srajan Tyagi

2019BALLB107

Page |4 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE................................................................................................................................2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT...............................................................................................................3

TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................4

NAME OF THE CASE:..................................................................................................................5

DATE OF THE JUDGEMENT:......................................................................................................5

CITATION OF THE JUDGEMENT:.............................................................................................5

TYPE OF BENCH:..........................................................................................................................5

HONOURABLE JUDGES:.............................................................................................................5

NUMBER & TYPE OF OPINIONS:..............................................................................................5

AUTHOR OF THE JUDGEMENT:................................................................................................5

COUNSELS REPRESENTING THE PARTIES:...........................................................................5

BACKGROUND.............................................................................................................................6

MATERIAL FACTS.......................................................................................................................6

ISSUES............................................................................................................................................7

CONTENTIONS.............................................................................................................................7

PROVISIONS OF STATUTES/CONSITUTION CITED..............................................................7

DOCTRINES/THEORIES/CONCEPTS INVOKED......................................................................7

LITEREATURE CITED.................................................................................................................8

PRECEDENTS CITED...................................................................................................................9

JUDGEMENT...............................................................................................................................10

REASONING................................................................................................................................11

CRITICAL ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSION............................................................................11

Page |5 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

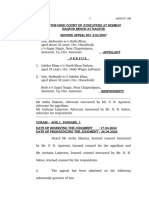

NAME OF THE CASE:

R. KEMPRAJ V. BARTON SONS AND CO.

DATE OF THE JUDGEMENT:

29TH AUGUST,1969

CITATION OF THE JUDGEMENT:

AIR 1970 SC 1872

TYPE OF BENCH:

IT WAS A SPECIAL LEAVE APPEAL BEFORE A FULL BENCH OF THE SUPREME COURT.

HONOURABLE JUDGES:

JUSTICE A.N. GROVER, JUSTICE J.C. SHAH AND JUSTICE VAIDYNATHIER RAMASWAMI.

NUMBER & TYPE OF OPINIONS:

THE BENCH HAD A SINGLE OPINION AND A UNANIMOUS JUDGEMENT.

AUTHOR OF THE JUDGEMENT:

JUSTICE A.N. GROVER

COUNSELS REPRESENTING THE PARTIES:

PETITIONER: Adv. A.K. Sen; Adv. Shyamala Pappu: Adv. Vineet Kumar.

RESPONDENT: Adv. S.V. Gupte; Adv. Janendra Lal; Adv. B.R. Agarwala; Adv. Kumar M.

Mehta.

INTERVENORS/ AMICUS: No Amicus Curie or Intervenor was present in the Court.

Page |6 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

BACKGROUND

The current case had reached the Apex court by the way of a Special Leave Petition under

Article 136 of the Indian Constitution 1, by the respondent against the verdict of the Hon’ble

Mysore High Court. Before the verdict of the appellate High Court, initially the Plaintiff had

filed a suit for specific performance against the defendant, which the Trial court also agreed with

and thus granted the decree. After which the defendant naturally filed an appeal in the High

Court and further in the Supreme Court in anticipation of a favourable verdict.

Thus, the matter stood before the Supreme Court, which on 29 th of August in 1969 settled the

issue while setting a landmark case in Property Jurisprudence.

MATERIAL FACTS

The main subject matter of the case deals with a Lease deed between the petitioner and the

respondent. So, both the parties entered a deed of lease on October 26, 1951 which was initially

stipulated for a time period of 10 years i.e., till November 1, 1961.

Now the point of contentions arose on a certain clause of said deed which allowed for a renewal

of the lease deed if applied by the leasee any time before the expiry of the current deed period of

10 years, for the similar period of time (10 years) and under the same conditions such as the

original lease deed. Further, the lessee couldn’t transfer this deed to any 3 rd party; also, it was

provided that the lessor would not object to such renewal as long as all the stipulations were met

with.

Now, sometime before the expiry of these initial 10 years i.e., before November 1, 1961 the

lessee showed his intention to renew his lease in the same conditions as were previously

stipulated. But the lessor refused to comply with such request. Then, upon serving a notice to the

lessor the lessee filed before the Tribunal Court for a decree of specific performance.

1

India Const. Art. 136.

Page |7 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

ISSUES

The court very suitably formulated the following issue/s pertaining to the said case: -

Whether the deed in question, subject to the renewal clause is hit by Section 14 of

TPA2, and accordingly void?

Hence, the issue thus formulated was a mixed question of fact and law.

CONTENTIONS

1. PETITONER

a. Petitioner contends that the current lease deed isn’t remotely concerned with §14

of TPA.

2. RESPONDENT

a. On the other hand, the primal argument of the respondent i.e., the lessor is that the

lease is inherently void as it is hit by the rule against perpetuity has mentioned u/s

14 of TPA.

3. INTERVENORS/AMICUS

Not Applicable.

PROVISIONS OF STATUTES/CONSITUTION CITED

The Transfer of Property Act,1883.

Section 5: “Transfer of property” defined.

Section 14: Right Against Perpetuity

Section 40: Burden of obligation imposing restriction on use of land, or of obligation

annexed to ownership but not amounting to interest or easement.

Section 105: “Lease” defined.

2

Transfer of Property Act, 1883, Act. No. 4, Acts of Parliament.

Page |8 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

DOCTRINES/THEORIES/CONCEPTS INVOKED

LIBERTY OF ALIENATION

The doctrine dictates that an inherent right which comes along a property is the right to

alienate it. Once a person owns a property in all regards, he has the exclusive right to

dispose off said property however he wants to. Thus, a hindrance in the right of the owner

in regards to alienation is generally considered null and void and the owner can enjoy the

property as if such an impediment was never there. [This rule is subject to exceptions in

the contemporary world]

RULE AGAINST PERPETUITY

This rule which has been a part of English common law from as back as 1600s, dictates

and prohibits a successive vertical transfer of property. It says that a property might be

transferred to any number of living people but in case of an unborn person the property

may only pass once i.e., no two unborn persons can be declared as successive future

owners of any property [son → grandson]. It is such, so as to prevent the perpetual

transfer of property in one’s own kin, as it contravenes the liberty of alienation of such an

unborn owner who even though should have a complete interest can only enjoy said

property as limited interest.

LEASE

A Lease of property is a transfer of the right to enjoy such property for a time period, or

even for perpetuity.

LITEREATURE CITED

Halsbury's Laws of England3 by Edward Jenks

Halsbury's Laws of England is a uniquely comprehensive encyclopaedia of law, and

provides the only complete narrative statement of law in England and Wales.

It was cited to enunciate how in English law a covenant for even a perpetual renewal

would not be hit by the rule of perpetuity as long as the intention was clear.

Transfer of Property Act4 by Mulla

3

Edward Jenks, Halsbury’s Laws of England, Fourth Edition, Vol. 24, 1907.

4

Sir D.F. Mulla, Transfer of Property Act 1882, 13th edition, 2018.

Page |9 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

It’s a classic section wise analysis of the primary legislation in respect of property

matters.

It was cited to explain how section 40 of TPA wouldn’t affect the current case scenario in

any way.

PRECEDENTS CITED

A. INDIAN JUDGEMENTS

1. Ganesh Sonar v. Pumendu Narayan Singha and Ors.5

In the Patna High Court, a case was decided where it distinguished the English

law from the contemporary Indian law. It explained how after the enactment of

TPA no mere contract of sale of property can’t be considered as transfer of

property and thus s.14 would not be attracted.

It was cited to directly affect the decision of the current case and the legal analysis

was spot on and very pertinent to the current case.

B. FOREIGN JUDGEMENTS

1. Woodall v. Clifton6

In this case “it was held that a proviso in a lease giving an option to the lessor to

purchase the fee simple of the land at a certain rate was invalid as infringing the

rule against perpetuity”.

It was cited as this case was distinguished by the Patna High Court in Ganesh

Sonar.

2. Midler v. Traffword7

In said case Justice Farwell held that the covenant in a lease for renewal was not

strictly a covenant for renewal but was a covenant running with the land thus free

form the rule of perpetuity.

It was cited to explain the English law on the regard of running covenants,

renewal clauses and rule of perpetuity.

3. Weg Motors Ltd. v. Hales and Ors.8

5

Ganesh Sonar v. Pumendu Narayan Singha and Ors. (1962) Patna 201.

6

Woodall v. Clifton (1905) 2. Ch.257 [UNITED KINGDOM].

7

Midler v. Traffword (1901) 1 Ch.54 [UNITED KINGDOM].

P a g e | 10 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

Justice Farwell yet again observed, “But now I will assume that this is a covenant

for renewal running with the land; it is then in my opinion free from any taint of

perpetuity because it is annexed to the land.”

It was cited again for the reason of drawing corelation to running covenants,

renewal covenants and rule of perpetuity.

4. London & South Western Rly. v. Gomm9

Sir George Jessal held that if a covenant “binds the land it creates an equitable

interest in the land.”

It was cited to be distinguished from the Indian jurisprudence that a covenant can

never create an interest in the property as TPA does not provides for it.

JUDGEMENT

In Personam [CONCRETE JUDGEMENT]

The Appeal was dismissed and the verdict from the tribunal was upheld, that is the decree

was granted and the lessor was made to oblige the renewal of the lease according to the

deed.

In Rem [RATIO DECIDENDI]

The judgement dealing with quite a unique case also delivers a quite unique and case

specific RATIO:

In cases where a similar kind of covenant relating to the renewal of lease deed would be

of question, the covenant and thus the deed would not be hit by the rule of perpetuity u/s

14 of TPA.

8

Weg Motors Ltd. v. Hales and Ors. [1961] 3 A.E.I.R.181[UNITED KINGDOM].

9

London & South Western Rly. v. Gomm [1882] 20 Ch.D.562 [UNITED KINGDOM].

P a g e | 11 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

REASONING

The judgement is comprised of various cases mostly from English Jurisprudence along with

commendable commentaries on the subject matter “Rule against perpetuity” to substantiate their

decision. Firstly, the court clears basic terminologies and concepts relating to the matter at hand

like ‘Transfer of Property’ which is the conveyance of property among living beings; ‘Lease’

which is not a mere contract but the transfer of a right to enjoy and thus creates an interest in the

land in rem; finally, ‘Rule Against Perpetuity’ the court summarises s.14 of TPA and explains

the intention and nexus behind said rule which is protection of the right of alienation.

Now, the court’s first line of reasoning begins from the fact that s.14 is to apply only in cases of

Transfer of Property. Here, even if a lease deed is considered under the expression of ‘transfer of

property’, such transfer is technically only for 10 years; any covenant of renewal does not create

any interest in lease property but only renews the prior already existing one. Thus, as this

covenant does not create any interest in the property it can’t be said to be in the ambit of ‘transfer

of property’ and thus can’t be hit by the rule of perpetuity.

This point is further substantiated by a Patna High Court decision Ganesh Sonar v. Pumendu

Narayan Singha and Ors.10 Where there was a covenant in the lease deed which allowed the

lessor to take possession of the lease property in specific conditions, this was in turn in

contravention of English law which said a covenant which allows the lessor to buy lease property

for a fee simple is void as it’s hit by the rule of perpetuity. The Patna High Court distinguished

this English law form the Indian perspective as after passing of TPA no mere contract of sale of

immovable property can create any interest in the property, thus in Ganesh Sonar the option

given by the lessee to the lessor to resume the lease hold land was only a personal covenant and

thus saved from the application of s.14. Thus, this case was directly applied on the present case

as such covenant of renewal is only a personal covenant and no way creates and interest and thus

isn’t hit by the rule of perpetuity.

The next point arises is whether such a renewal covenant is a covenant running with the land.

Landmark English cases in these regards were cited which established that a covenant for

renewal would be a covenant running with the land and thus no question of perpetuity would

10

Supra, see note 5.

P a g e | 12 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

arise. Further, the provision for such covenants in the TPA, s.40 was discussed. But the Indian

law was distinguished by the English counter part by the help of Mulla’s commentary on

Transfer of Property Act, which elucidated the fact that right of the covenantee cannot be

considered as an interest in the property for the reason that TPA does not recognises the concept

of equitable estates; in simple words as a mere contract/covenant can only be considered as much

as a sale of property but in no way a ‘transfer of property’.

Justice A.N. Grover then very beautifully concluded by explaining that, “Even on the footing

that the clauses relating to renewal in the lease, in the present case, contain covenants running

with the land the rule against perpetuity contained in Section 14 of the Act would not be

applicable as no interest in property has been created of the nature contemplated by that

provision.”

CRITICAL ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSION

The present is a landmark judgement in the explanation and application of s.14 of TPA and till

this day is taught and used as an important authority. When a lessor attached a renewal clause to

a lease deed, he was by natural law bound by his own covenant, but when the lessee wanted to

enforce this provision and renew his lease for another 10 years the lessor goes back on his word

refuses to honour the deed, and further even challenge its validity till the Apex Court on the

superficial ground that it violates the rule against perpetuity as enshrined u/s 14 of TPA.

The judgement itself is not the most comprehensive one but it quite clearly explains all the point

that the court touched upon while coming onto the decision that such a covenant would not be hit

by the rule of perpetuity. It goes on to first explain how all these concepts work in contemporary

jurisprudence, by the help of commentaries, judgements though of lower jurisdiction and

authority but still embraced as they give perfect logical reasoning. Further, the judgement is also

an important authority on interplay of various aspects and concepts of Property law

Jurisprudence.

The bench very selectively dissects the rule of perpetuity which is found u/s 14 of TPA i.e., they

explain how rule of perpetuity might very well be applicable in case of a lease deed which is

even though only a transfer of right to enjoyment but is still very well a ‘transfer of property’.

But a mere covenant which is present in said deed does would in no way be hit by the rule of

P a g e | 13 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

perpetuity as such a covenant may only create an obligation of sorts to follow but never under

the TPA a covenant may create an interest in suit property, and as the rule of perpetuity may only

be invoked when an actual transfer has happened i.e., an actual vesting of interest.

The latter half of the judgement, it is contemplated by the court whether such a covenant would

be considered a covenant running with the land. By a comparison of English law and s.40 of

TPA which deals with any Burden of obligation imposing restriction on use of land, or of

obligation annexed to ownership but not amounting to interest or easement. Which in affect

explains the concept of such negative covenants and covenants running with land and how would

be binding on the successive transferees given they had a notice of such a covenant. Finally, it is

explained that even if such a covenant might be running with the land it would not be hit by the

rule of perpetuity as the TPA has never recognised the concept of an equitable estate is nowhere

to be found under the principal law relating to properties in India TPA, in essence which means

that by the way of a covenant no real interest may be created in any property.

In the personal opinion of the researcher the judgement was fairly a small one spanning only 4

pages including the citations in effect only approx. 1500 words long. The themes and concepts

discussed and talked about in the decision are quite vast and comprehensive and in researcher’s

personal opinion four A4 sized pages don’t do these topics/ concepts justice for example the

correlation of rule of perpetuity and s.40 was discussed in a very hasty and complicated matter

which could only be understood by prior thorough research and knowledge on the topic. Now,

this might not be a problem for the legal fraternity but as law is a social phenomenon it should be

accessible to the common man, which to be honest wouldn’t be possible by the quality and

intricacy of this ruling. On the contrary a leeway might be given to the fact that the said

judgement is 42 years old and much has changed since then i.e., this sentiment of accessibility of

law to common man would’ve only concerned with the upholding of law and order and

providing justice to members of the society.

In researcher’s regards this special appeal was only a last desperate attempt of the lessor aimed at

protecting his own interest in said property which was already waived off when he signed on the

lease deed containing a covenant for the renewal of deed. Now objectively speaking the case

does not even remotely touch or tread upon the territory of ‘rule of perpetuity’. S.14 only

provides that a property might be perpetually transferred among living beings but to only one

P a g e | 14 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

unborn person i.e., a father can’t create a remote interest in the property for his son then his

grandson then his grand-grandson and further on. So, in effect s.14 deals and prohibits

successive vertical transfer of property. Coming to the case at hand no such scenario is apparent

the transfer was only a single fold and that too in the favour of a living being; on the flip side as

already explained s.14 only deals with ‘transfer of property’ and obviously a personal covenant

would be excluded form this definition. In researcher’s opinion apparently the respondent’s

contentions were based on the fact that this renewal clause may extend to perpetuity and this the

closest provision which he sought fit to apply was s.14 rule against perpetuity completely

ignoring the actual meaning and application of the provision.

Finally, the researcher wants to point out how Indian jurisprudence has outgrown and developed

form its original English common law [strictly in regards of Property Law Jurisprudence]. It

was very evident form the rulings of Patna High Court and even the case at hand that the Indian

jurisprudence has developed into something different and independent of the original English

common law. The most important instance from this judgement, TPA does not recognises the

idea of Equitable Estates even though the traditional English law does but still outgrowing the

colonial common law India doesn’t recognises such superficial concepts. Thus, even in very

small regards India has matured from England’s initial common law though it is still very much

prevalent in other aspects (TPA itself is a colonial law) but still its commendable and gives us a

positive light for the future where India respecting its own sovereignty create/amend/codify laws

which are completely indigenous. This hope could be realised sooner than expected as recently

there were news of overhauling the colonial criminal law which is still being followed after 73

years of Independence.

P a g e | 15 Case Analysis: R. Kempraj v. Barton Sons and Co.

You might also like

- Karan CPC FinalDocument13 pagesKaran CPC Finalkaran aroraNo ratings yet

- LEGAL METHODS Prabhu DayalDocument16 pagesLEGAL METHODS Prabhu DayalShivam TiwaryNo ratings yet

- 2nd Moot Memorial Defendant AmolDocument15 pages2nd Moot Memorial Defendant AmolAmol NavalpureNo ratings yet

- Before The Learned District Court of BurnpurDocument13 pagesBefore The Learned District Court of BurnpurashiNo ratings yet

- Legal Methods 2Document16 pagesLegal Methods 2Devvrat TyagiNo ratings yet

- 004 - 1977 - Law of Property PDFDocument28 pages004 - 1977 - Law of Property PDFMuruganNo ratings yet

- Prem Singh Vs BirbalDocument10 pagesPrem Singh Vs Birbalajay narwalNo ratings yet

- Before The Honorable Supreme Court of India: M.S. Bansal (PVT.) Ltd. and Anr. V. Bhagwan Swarup Mathur and OrsDocument10 pagesBefore The Honorable Supreme Court of India: M.S. Bansal (PVT.) Ltd. and Anr. V. Bhagwan Swarup Mathur and OrsToshan Chandrakar100% (1)

- Pomal Kanji Govindji & Ors Vs Vrajlal Karsandas Purohit & Ors1988Document31 pagesPomal Kanji Govindji & Ors Vs Vrajlal Karsandas Purohit & Ors1988samiaNo ratings yet

- Ordjud 2Document11 pagesOrdjud 2CA Mihir ShahNo ratings yet

- University of North Bengal 22Document34 pagesUniversity of North Bengal 22Bodhisatya DeyNo ratings yet

- Moot Court Criminal AppellantDocument11 pagesMoot Court Criminal AppellantRikar Dini BogumNo ratings yet

- Case Comment CPC Project Work 19131Document12 pagesCase Comment CPC Project Work 1913119131 TATIREDDY KIRANKUMAR REDDYNo ratings yet

- Memorial of Civil LawDocument14 pagesMemorial of Civil Lawsaurabh shakya50% (2)

- Memo LegalDocument16 pagesMemo LegalDevvrat TyagiNo ratings yet

- Vishal ADR Law ProjectDocument14 pagesVishal ADR Law ProjectShivamPandeyNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis - Danamma@Suman Surpur Vs AmarDocument14 pagesCase Analysis - Danamma@Suman Surpur Vs Amardurgesh4yadav-14023No ratings yet

- BHARATHA MATHA v. R. VIJAYA RENAGANATHANDocument13 pagesBHARATHA MATHA v. R. VIJAYA RENAGANATHANMANASVI SHARMANo ratings yet

- Concept of Restrictive Covenant (TOPA)Document18 pagesConcept of Restrictive Covenant (TOPA)DIWAKAR CHIRANIANo ratings yet

- Tyr CPC MootDocument16 pagesTyr CPC MootAbinayaSenthil0% (1)

- K.T. Thomas and R.P. Sethi, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: AIR2000SC 2912Document11 pagesK.T. Thomas and R.P. Sethi, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: AIR2000SC 2912Deeptangshu KarNo ratings yet

- CPC ProjectDocument13 pagesCPC ProjectPrithish DekavadiaNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University, Bhopal: Common Law Method Case AnalysisDocument20 pagesNational Law Institute University, Bhopal: Common Law Method Case AnalysisSundram GauravNo ratings yet

- MemorialDocument12 pagesMemorialPtNo ratings yet

- SubjectDocument15 pagesSubjectravi prakash0% (1)

- National Law Institute University BhopalDocument11 pagesNational Law Institute University Bhopalgaurav singhNo ratings yet

- Case Law Review Limitation ActDocument9 pagesCase Law Review Limitation ActCHIRAYUNo ratings yet

- Topa Second Case ProjectDocument16 pagesTopa Second Case ProjectSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Burden of Proof and The Applicability of Principle of Presumption On DefendantDocument96 pagesBurden of Proof and The Applicability of Principle of Presumption On DefendantMullaiperiyar DamNo ratings yet

- Aatif Pe Final ProjectDocument16 pagesAatif Pe Final Projectraj100% (2)

- In The Hon'Ble Supreme Court of IndiaDocument10 pagesIn The Hon'Ble Supreme Court of IndiahjbkhbjtNo ratings yet

- Compulsory Moot - VishalDocument18 pagesCompulsory Moot - Vishaldishu kumar100% (1)

- LEJANO V BANDAKDocument7 pagesLEJANO V BANDAKIndia ContractNo ratings yet

- Gorman V AnsongDocument22 pagesGorman V AnsongBernard Nii Amaa50% (2)

- Contract Project .OokkDocument14 pagesContract Project .OokkPriyal AgarawalNo ratings yet

- 2020BALLB 100 Contracts Case AnalysisDocument29 pages2020BALLB 100 Contracts Case AnalysisShriyadita SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law Universi Ty: Bhagwandas V. Prabhati Ram and AnrDocument12 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law Universi Ty: Bhagwandas V. Prabhati Ram and AnrJeevan PramodNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics - Assignment NotesDocument12 pagesProfessional Ethics - Assignment NotesBangalore Coaching CentreNo ratings yet

- 2145 CPC Final DraftDocument13 pages2145 CPC Final DraftSachin KumarNo ratings yet

- Deva Ram and Another VS Ishwar ChandDocument14 pagesDeva Ram and Another VS Ishwar ChandsankalpmiraniNo ratings yet

- Session 2 - Case NotesDocument10 pagesSession 2 - Case NotesYash MayekarNo ratings yet

- Topa CaseDocument17 pagesTopa CaseSonia SabuNo ratings yet

- Memorail Santosh Sept 2019 V5Document20 pagesMemorail Santosh Sept 2019 V5Santosh Chavan Bhosari100% (1)

- Sra DefDocument18 pagesSra DefPRIYANKA NAIRNo ratings yet

- Yaksh Shah, Respondent 2Document13 pagesYaksh Shah, Respondent 2Yaksh ShahNo ratings yet

- BEN MIREKU & ANOR. v. ARCHIBALD OKPON TETTEH & 3 ORS.Document8 pagesBEN MIREKU & ANOR. v. ARCHIBALD OKPON TETTEH & 3 ORS.Dzandu KennethNo ratings yet

- Alternative Dispute Resolution AbstractDocument25 pagesAlternative Dispute Resolution AbstractNikhil KalyanNo ratings yet

- Ji ShanDocument6 pagesJi ShanChaw ZenNo ratings yet

- Case PresentqationDocument12 pagesCase PresentqationutkarshNo ratings yet

- ArgfvaDocument3 pagesArgfvaGrace Ann TamboonNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University BhopalDocument18 pagesNational Law Institute University Bhopalkratik barodiyaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: T. R. Reyes & Associates For Petitioner. Soleto J. Erames For RespondentsDocument3 pagesSupreme Court: T. R. Reyes & Associates For Petitioner. Soleto J. Erames For RespondentsRitz DayaoNo ratings yet

- Case Comment On Ramesh Kumar Agarwal V. Rajmala EXPORTS (P) LTD., AIR 2012 SC 1887 6.1 Code of Civil Procedure & Law of LimitationDocument11 pagesCase Comment On Ramesh Kumar Agarwal V. Rajmala EXPORTS (P) LTD., AIR 2012 SC 1887 6.1 Code of Civil Procedure & Law of LimitationVaishnavi Murkute0% (1)

- Mst. Kiran Chhabra and Anr. Vs Mr. Pawan Kumar Jain and Ors. On 14 February, 2011Document2 pagesMst. Kiran Chhabra and Anr. Vs Mr. Pawan Kumar Jain and Ors. On 14 February, 2011Sandeep KhuranaNo ratings yet

- FD - CPC and LimitationDocument13 pagesFD - CPC and Limitation19103 JOTSAROOP SINGHNo ratings yet

- Ang Yu Asuncion, Et Al. vs. Court of Appeals, Et Al. - Supra Source PDFDocument14 pagesAng Yu Asuncion, Et Al. vs. Court of Appeals, Et Al. - Supra Source PDFmimiyuki_No ratings yet

- Contracts Case AnalysisDocument29 pagesContracts Case AnalysisSuman sharmaNo ratings yet

- Stanley W. ROSENFIELD and The First National Bank & Trust Company of Oklahoma City, Trustees, Appellants, v. Kay Jewelry Stores, Inc., AppelleeDocument3 pagesStanley W. ROSENFIELD and The First National Bank & Trust Company of Oklahoma City, Trustees, Appellants, v. Kay Jewelry Stores, Inc., AppelleeScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- MemorialDocument7 pagesMemorialbhatiaanul0001No ratings yet

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Ir End TermDocument19 pagesIr End TermDeepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- Law and Urban DevelopmentDocument19 pagesLaw and Urban DevelopmentDeepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- Itl ProjectDocument11 pagesItl ProjectDeepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- IHL ProjectDocument19 pagesIHL ProjectDeepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- Juris New 2022Document21 pagesJuris New 2022Deepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- JALINGODocument15 pagesJALINGODeepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- Deepti CLMDocument10 pagesDeepti CLMDeepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence Project VII SEMDocument7 pagesJurisprudence Project VII SEMDeepti UikeyNo ratings yet

- AUSL Pre-Week Review On Civil Law II (Reduced Bar Coverage) Notes For RevieweesDocument163 pagesAUSL Pre-Week Review On Civil Law II (Reduced Bar Coverage) Notes For RevieweesKristine Fallarcuna-TristezaNo ratings yet

- Wagering AgreementDocument4 pagesWagering AgreementrahatNo ratings yet

- SUJEET JHA Indian Contract Act NotesDocument61 pagesSUJEET JHA Indian Contract Act Notes2050101 A YUVRAJ100% (1)

- Sales Cases 1-25 (Except No. 8)Document160 pagesSales Cases 1-25 (Except No. 8)Kay AvilesNo ratings yet

- SpecPro Rules 89-91Document18 pagesSpecPro Rules 89-91BananaNo ratings yet

- KMC Quitclaim - Jesly SaliganDocument2 pagesKMC Quitclaim - Jesly Saliganjercon vince olisNo ratings yet

- Re Lo Siong Fong - (1994) 2 MLJ 72Document9 pagesRe Lo Siong Fong - (1994) 2 MLJ 72Razali ZlyNo ratings yet

- Name: Rosel Joy A. Provido LLB Iii Wills and Succession S.Y. 2018-2019 Compulsory Heirs Combined With Legitime Under The Civil Code, As AmendedDocument3 pagesName: Rosel Joy A. Provido LLB Iii Wills and Succession S.Y. 2018-2019 Compulsory Heirs Combined With Legitime Under The Civil Code, As AmendedJui Aquino ProvidoNo ratings yet

- Case 1Document176 pagesCase 1EllieNo ratings yet

- ERECTION ALL RISKS - Policy WordingDocument14 pagesERECTION ALL RISKS - Policy WordingSudheer KumarNo ratings yet

- Vicente Vs GeraldezDocument13 pagesVicente Vs Geraldezroselleyap20No ratings yet

- Reyes Vs Baretto DatuDocument2 pagesReyes Vs Baretto DatunathNo ratings yet

- Talent ContractDocument2 pagesTalent ContractKatalyst JaNo ratings yet

- CH 1nature and Classification of ContractsDocument13 pagesCH 1nature and Classification of ContractsRam KapoorNo ratings yet

- COMM 229 Notes Chapter 6Document5 pagesCOMM 229 Notes Chapter 6Cody ClinkardNo ratings yet

- OTL Exam E Answer Key NewDocument16 pagesOTL Exam E Answer Key Newpatrick Muyaya100% (1)

- Extra Judicial Settlement With WaiverDocument3 pagesExtra Judicial Settlement With WaiverAtty Reynan Dollison86% (7)

- Modes of Extinguishment of ObligiationDocument4 pagesModes of Extinguishment of Obligiationpatricia louise montejoNo ratings yet

- LeasingDocument19 pagesLeasingHassan IjazNo ratings yet

- Honda Tour: Letter of IndemnityDocument2 pagesHonda Tour: Letter of IndemnityDr Bugs TanNo ratings yet

- Aplha Insurance v. CastorDocument3 pagesAplha Insurance v. CastorRoger Montero Jr.No ratings yet

- California LLC Operating Agreement Short Form ExampleDocument11 pagesCalifornia LLC Operating Agreement Short Form ExampleRandy HuiNo ratings yet

- Omnibus IndemnityDocument4 pagesOmnibus IndemnityNitin UpretiNo ratings yet

- Assured Shorthold TenancyDocument6 pagesAssured Shorthold TenancyArsalanNo ratings yet

- WORK FioranoMQHandBook PDFDocument438 pagesWORK FioranoMQHandBook PDFJayath GayanNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Ypon v. PonterasDocument3 pagesHeirs of Ypon v. PonterasCzarina CidNo ratings yet

- Option Market Making - Trading and Risk Analysis For The Financial and Commodity Option Markets (PDFDrive)Document221 pagesOption Market Making - Trading and Risk Analysis For The Financial and Commodity Option Markets (PDFDrive)ЛайдNo ratings yet

- Causation & RemotenessDocument5 pagesCausation & Remotenessdharani shashidaranNo ratings yet

- Hints On Answering Problem QuestionsDocument2 pagesHints On Answering Problem QuestionsLij SinclairNo ratings yet

- CR BuildEyeSetupDocument2 pagesCR BuildEyeSetupQAZwsx13No ratings yet