Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ndered Experiences of Mobility - Travel Behavior of Middle-Class Women in Dhaka City (Transfers, Vol. 3, Issue 3) (2013)

Uploaded by

kemala firdausiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ndered Experiences of Mobility - Travel Behavior of Middle-Class Women in Dhaka City (Transfers, Vol. 3, Issue 3) (2013)

Uploaded by

kemala firdausiCopyright:

Available Formats

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

Travel Behavior of Middle-class Women

in Dhaka City

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

University of Dhaka

Abstract

This article examines the travel behavior of middle-class women in Dhaka,

the capital city of Bangladesh and one of the world’s largest and most densely

populated cities. In particular, we focus on women’s use of non-motorized

rickshaws to understand the constraints on mobility for women in Dhaka. Pri-

mary research, in the form of an empirical study that surveyed women in six

neighborhoods of Dhaka, underpins our findings. Our quantitative and quali-

tative data presents a detailed picture of women’s mobility through the city. We

argue that although over 75 percent of women surveyed chose the rickshaw as

their main vehicle for travel, they did so within a complex framework of limited

transport options. Women’s mobility patterns have been further complicated

by government action to decrease congestion by banning rickshaws from major

roads in the city. Our article highlights the constraints on mobility that middle-

class women in Dhaka face including inadequate services, poorly maintained

roads, adverse weather conditions, safety and security issues, and the difficulty

of confronting traditional views of women in public arenas.

Keywords

cycle rickshaw, Dhaka city, middle class, rickshaw ban, women

Introduction

The primary question of this study, how middle-class women experience

travel in Dhaka City, Bangladesh, connects obviously and clearly to a broad

understanding of mobility.1 Women move about the city for numerous rea-

sons, including travelling to workplaces and educational institutions, or to

accompany children to school and take elderly relatives to hospitals. In the

process they may undertake journeys by foot, or by one of the many options

for vehicular transport. Within Dhaka, these modes of transport range from

the rickshaw (both non-motorized and motorized versions) to public trans-

port such as buses and private transport such as bicycles, scooters, and cars.

Transfers 3(3), Winter 2013: 79–98 ISSN 2045-4813 (Print)

doi: 10.3167/TRANS.2013.030306 ISSN 2045-4821 (Online)

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

Dhaka has a high proportion of pedestrian traffic with estimates suggest-

ing that over 60 percent of daily travel is undertaken by foot.2 Many of these

daily journeys undertaken by its citizens, particularly women, take the form

of multi-part trips that connect bodily movement to vehicular movement of

various kinds and in various combinations—a creation of “chain trips” that

map everyday activity onto the geography of the city.3

Yet, as Tim Cresswell notes, the mobility paradigm invokes more than

physical movement; instead, it becomes an “ethical and political issue.”4 The

subject of our study exemplifies this “mobilities approach;” research in travel

behavior within South Asian countries indicates gender difference in the con-

text of cultural and socioeconomic conditions. Much of this difference stems

from the long-established social attitude towards women’s traditional roles as

homemakers and caregivers for children and the elderly in their families. As

such women’s mobility outside their homes was largely restricted irrespective

of their religion or social class. Thus, in examining the pattern of middle-class

women’s movement in Dhaka, we need also to consider how the social mi-

lieu for women in Bangladesh intersects with and impacts on the transporta-

tion flows within Dhaka itself. This more comprehensive framework means

that travel within the city must be interrogated as an experience that “lies at

the centre of constellations of power, the creation of identities and the micro-

geographies of everyday life.”5 That is, through our surveys and interviews, we

examine middle-class women’s travel in relation to their position and pro-

file in society; their interactions with people, places and objects connected

to travel around the city; and the way they negotiate movement from place

to place in a society that has not always encouraged the presence of women

in the public sphere. Thus, our discussion is not only about mobility, but it is

more specifically about the gendered experience of mobility.

The gendered experience of mobility in Dhaka needs to be understood

within several contexts: the historical context of purdah; the development of

Dhaka as a city and its transportation patterns; and recent attempts by local

and national governments to improve women’s position in Bangladeshi so-

ciety, including access to transport. As Cresswell has observed, the mobility

paradigm enables us to link together different elements and scales of move-

ment; thus, this contextual information is significant as it will deepen readers’

understanding of middle-class women’s mobility patterns in Dhaka.6 Back-

ground information provided in the next section will be developed further in

later sections of the article when we examine the responses from our survey

and interviews.

The practice of purdah is a religious and social norm that developed from

segregation of the sexes and respect for family traditions into the seclusion of

girls and women away from the public eye. The observation of purdah may

mean physical separation of women and girls within the household or the

covering up of their bodies outside their family spaces.7 Although purdah has

80 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

not been uniformly observed in Bangladeshi society across time and place, it

is an important part of our discussion as it contributes to restrictions on wom-

en’s mobility and visibility in public space.8 Purdah is often seen as a strict

imposition of limitations on female mobility within a patriarchal society, yet

the interpretation of religious teachings that restrict women’s movement may

be flexible: a woman’s economic status, age, religion, and geographic location

may all mitigate the impact that purdah may have on individual women or,

more broadly, groups of women in specific communities.9

The practice of purdah is generally seen as more prevalent in rural areas

than in major urban areas; however, steadily increasing migration from ru-

ral areas into Dhaka and the existing cultural norms of the city have meant

that purdah is an important factor in women’s visibility and ability to access

transport. In a report investigating gender and transport in the metropolitan

areas of Dhaka in 1997, Pratima Paul-Majumder and Masuda Khatoon identi-

fied purdah as a “dominant part of the culture” that would continue to restrict

women’s access to public transport in the city.10 Nevertheless, more recently,

Kamal Siddique and his colleagues reflected that conditions for women have

“come a long way from the strict purdah observed by Dhaka women in the

1950s.”11 An alternative view is provided by Salma Islam, who identified Dhaka

as less conservative, and therefore less dominated by strict observation of pur-

dah, than other Bangladeshi cities such as Chittagong and Noakhali, largely

because of the historical and contemporary opportunities for women’s work

in Dhaka.12 Growth in women’s employment opportunities, especially within

the garment-manufacturing industry, means that working-class women are

more visible on Dhaka’s streets. Increasing educational opportunities for

young women have also led to a decrease in the strict observance of purdah,

as well as the need for middle-class women to negotiate city life on behalf of

their families—shopping or taking children to school, for example. Thus, the

mobility of women has expanded and the attitude towards women travelling

around the city for various reasons has also changed.

Understanding the historical development of Dhaka is also integral to un-

derstanding the changing patterns of women’s mobility. Dhaka is the capital

city of Bangladesh and is also the national center for much of the adminis-

trative, financial, and manufacturing activity of the country, consequently

attracting large numbers of migrants from rural areas. Geographically, it is sit-

uated in the middle of the country, on the north-eastern side of the Buriganga

River.13 Dhaka was world-renowned for its muslin industry in the Mughal pe-

riod (fifteenth to sixteenth centuries). This industry, which was capitalized on

by foreign traders, especially during the British period, is significant because

it embedded women’s employment in the area well before the recent phase

of globalization; indeed, Islam notes that women’s historical “participation

in the paid labor force in Dhaka has been higher than in any other part of the

country.”14

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 81

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

With the partition of British India in 1947, Dhaka became the provincial

capital of East Pakistan. The mass migrations that accompanied partition had

a significant impact on Dhaka as its Hindu population diminished and was

replaced with a Muslim majority. The struggles in Muslim politics between

East and West Pakistan in the 1960s culminated in the War of Liberation in

1971 and the birth of the independent nation of Bangladesh. Dhaka evolved

from a provincial capital into a national capital and became one of the

fastest-growing cities in Asia. The impoverished situation of the war-torn

country worsened and more women from poor families engaged in work out-

side the home to contribute to their family income; similarly, families from

poor rural areas migrated to the city to find employment. In the late twentieth

century, the population of Dhaka comprised about 25 percent of Bangladesh’s

urban population and the city grew at an average annual rate of 7 percent, put-

ting extreme pressure on the provision of adequate housing and infrastructure

for its inhabitants.15 Dhaka City, administered by the Dhaka City Corporation

(DCC), is now the largest single urban concentration in Bangladesh, with a

population currently in excess of 15 million and projected to grow beyond 25

million by 2025. The city is divided into four zones and seventy-five municipal

wards, with twelve thanas (see figure 4).16

As Siddique et al. point out, population growth has far outpaced the city’s

ability to plan, build and maintain roads.17 Narrow and unplanned lanes and

roads continue to emerge alongside larger infrastructure projects supported

by financial institutions such as the World Bank. These narrow lanes are pres-

ent mostly in areas inhabited by the lower middle class and in the unplanned

Zones 1 and 3, where most of the city’s poor and working class live. Zone 4, the

area occupied by the upper middle class and the wealthy, is serviced by wider

roads. In 2005, less than 10 percent of residential roads in Dhaka were wide

enough for two cars to pass each other, while over half of residential roads

were so narrow that they would only allow two rickshaws, or one rickshaw

and one car, to travel side-by-side.18 Residents of Zones 3 and 4, in particular,

highlighted these narrow or unsuitable roads and lack of road repair as major

and ongoing civic concerns.19

Similarly, the number of motorized vehicles is not increasing as per the

needs of the city population. A study by Mannan and Karim shows that in the

year 2001 there were only 2,630 vehicles (all types) per 100,000 population of

Dhaka and among these about 2,195 were non-motorized vehicles, mainly the

human-driven three-wheeler cycle rickshaws.20 According to a World Bank

study non-motorized transport (NMT) contributes significantly to the trans-

port system of Dhaka and cycle rickshaws are the notably preferred mode of

transport by middle-class people.21

The city’s growth has also meant a growth in crime and general percep-

tions of safety and security. In Siddique et al.’s gathering of statistical data

on Dhaka in 2005, crime (related mostly to theft, robbery and hijacking) was

82 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

mentioned as one of the two most pressing civic problems by inhabitants in

all four Zones.22 Eighty-six percent of respondents in this important longitudi-

nal study suggested that the position for women was “insecure” in Dhaka City,

with the worst problems perceived in Zone 2. Women in public places, espe-

cially at night, were believed to be at risk of harassment or attack, including

hijacking and rape.23 These complex factors of Dhaka’s growth clearly have a

direct relationship to the availability and accessibility of transport for women

in the city.

Our study also needs to be placed in the context of broader social and po-

litical goals in Bangladesh in the last part of the twentieth century and in the

early parts of the twenty-first century. Salma Chaudhuri Zohir, in her case

study of gender issues in transport in Bangladesh (a project completed un-

der the auspices of the Dhaka Urban Transport Project, with support from the

World Bank) methodically notes the political framework for advancing wom-

en’s rights in Dhaka.24 For example, men and women have formal equality

within the Constitution of Bangladesh, with various articles specifying equal-

ity before the law and equal rights in “all spheres of the state and of public

life.”25 Bangladesh also ratified the Convention on Elimination of All Forms

of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), with some reservations in 1984.

However, Zohir also notes that, despite the preparation of the National Land

Transport Policy (drafted in January 2003), the issue of gender in transport

policy and practice was often overlooked. In the report, Zohir argues that

“several policy objectives could promote gender equality,” including safe, re-

liable and environmentally sustainable transport.26

Modes of Transportation in Dhaka

The available literature does not provide much specific detail about the forms

of transport that existed in the city before the seventeenth century; however,

it can be assumed that people in the past used to move in and around the city

mostly on foot—as they still do now. Other modes of transport in the city were

boats, horse-driven carts (tonga), and bullock and push carts. For the upper

classes, the horse-drawn palanquin was the main form of transport. Huq in-

dicates that the boats that linked the city with other parts of the country were

the primary means of transport in seventeenth-century Dhaka.27 These boats

were also used to travel within the city’s numerous canals and water bodies.

During the British period few cars were introduced on the roads of Dhaka;

the most significant development of transport and the overall expansion of

the city started when Dhaka became the capital of East Pakistan and later the

national capital of Bangladesh. Motorized transport such as buses were intro-

duced in the city but cycle rickshaws and push carts were the common non-

motorized vehicles which plied almost all roads.

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 83

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

According to Zohir, when the World Bank began its appraisal of roads and

transport in Dhaka in the late 1990s, the following patterns were noted: non-

motorized transport (NMT) and walking comprised the majority of mobility

modes, with almost 60 percent of Dhaka’s inhabitants walking to work. Ad-

ditionally, 19.2 percent engaged manually pedaled cycle rickshaws while

a much lower number (1.4 percent) used auto-rickshaws. These are locally

known as auto tempos or CNGs, and are improvised vehicles, powered by

compressed natural gas (CNG), with long seats on both sides that can carry

eight to ten passengers. The study also noted that some 9.2 percent of Dhaka’s

inhabitants travelled by bus, while 3.1 percent used private cars, and the re-

maining 7.7 percent of local travelers employed other modes.28 More recently,

these figures have been updated in a study of traffic conditions by Mahmud,

Gope and Chowdury, who observed that buses are now more in use than in

the latter decades of the twentieth century, operated by both private compa-

nies and the state-run Bangladesh Road Transport Corporation (BRTC). The

authors also identified Dhaka’s traffic system as “one of the most chaotic ones

in the world,” and noted that rickshaws (both cycle and auto) dominate the

city’s roads. There are conflicting reports on the current number of rickshaws

in Dhaka: according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, in 2011 there

were 121,702 registered rickshaws and 84,776 non-registered rickshaws in

the Dhaka metropolitan area.29 However, Mahmud and his colleagues suggest

that almost 400,000 rickshaws are in circulation in the city each day although

only a relatively small number (about 85,000) of these are licensed by the city

government.30 They also believe that this is the largest number of rickshaws

operating in any city in the world, and like Zohir, they agree that the cycle

rickshaws are non-polluting and low-cost as well as offering accessible em-

ployment to poorly educated workers, many of whom are recent arrivals from

impoverished rural areas; however, all authors agree that the cycle rickshaws

are a significant factor in the growing traffic problems in Dhaka.31

Despite this negative profile of rickshaws, they are the most common ve-

hicle for travel for women in the city, particularly for those from the lower

and middle classes. This is for a number of reasons: they are more convenient

than other public modes of transport such as auto rickshaws and buses; taxi

cabs are less available in the city and tend to be expensive; and the cycle rick-

shaw is the only kind of vehicle that can be ridden in any neighborhood of the

city, many of which have narrow streets and lanes; thus, passengers can use

rickshaws for door-to-door service. Conversely, traveling on public transport

such as buses can be difficult for women because of the various kinds of ha-

rassment and abuse by the drivers, helpers, and some male travelers. This is

particularly the case when women must compete for seats with men in rush

hour in overcrowded buses. In their rush to complete journeys, bus drivers

sometimes start moving before passengers have boarded. Passengers then run

to catch the bus and many women are injured in such circumstances. Thus,

84 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

for women the rickshaw has been the preferred and main mode of transport

in the city. It may be noted here that the huge number of low-income women

who work in the readymade garment industry may walk for long distances

to save money on transport. But these women, who often have to travel after

dark, are always fearful of sexual harassment in the street due to the absence

of safe and secure transport facilities and street lights. For safety reasons, they

prefer to ride in rickshaws when they travel at night to their place of residence

in the poor neighborhoods. They also feel that the rickshaw pullers are their

escorts and can help them in case of any problem. Rickshaws are also chosen

by women for traveling in adverse weather conditions ensuring safety and se-

curity. On a lighter note, rickshaws may also offer privacy, providing a space

for romantic expression for young couples. As the rickshaw is central to our

discussion, we provide now some history of the vehicle and its use in Dhaka.

The word “rickshaw” comes from the Japanese word “jin riki sha,” which

literally means “man-powered vehicle.”32 The name was originally given to

the hand-pulled rickshaw which was seen in Asian cities in the 1920s and

1930s, but Gallagher suggests that it also applies to the cycle rickshaws of In-

dia and Bangladesh.33 The first cycle rickshaw in Bangladesh was introduced

in the 1930s. Rashid states that “in 1938, a Bengali Zamider of Sutrapur and

a Marwari Gentleman of Wari area of Dhaka purchased about six rickshaws

each to introduce them in the town.”34 According to Banglapedia (the national

encyclopedia of Bangladesh), “this new imported vehicle from Calcutta cre-

ated huge curiosity among the people of Dhaka.” Despite this curiosity, the

number of rickshaws increased slowly, from only 37 rickshaws in 1941 to 181

rickshaws in 1947.35 The first licensed rickshaws plied the city roads during the

British period in 1944. The growth of cycle rickshaws up to 1989 in Dhaka has

been studied by Amin (see Table 1).36

After the introduction of rickshaws in Dhaka in 1944, women used this ve-

hicle mainly for occasional social visits but under strict purdah. The rickshaw

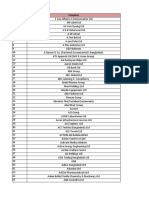

Table 1: Trend in growth of rickshaw numbers in Dhaka

Year Number of Rickshaws Remarks

1938 6 Rickshaw industry begins

1944 100 British first licensed rickshaw

1960 4,000 Denotes early sixties figure

1967 18,000 Liberal licensing policy of the Dhaka Municipality

Chairman Contributed to this big increase.

1978 40,000 Lower bound

1987 100,000 Upper bound

1989 300,000 Upper bound

Source: A.T.M. Nurul Amin, “Dhaka’s Informal Sector and Its Role in the Transformation of Bangla-

desh Economy”, in DHAKA Past Present and Future, ed. Sharif Uddin Ahmed (Dhaka: The Asiatic

Society of Bangladesh, 1991), 455.

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 85

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

was wrapped with a long cloth so that the passenger could not be seen by

those outside; the rickshaw pullers were also well trusted. With the expan-

sion of women’s education rickshaws became the prime mode of transport to

take young women to educational institutions and for other visits. The role of

women in the society has changed over time and they are increasingly con-

tributing to the economy of their families and the country by providing vari-

ous services and cash earnings. Such social and economic liberalization of

women is reflected in the changing pattern of the rickshaw appearance from

completely wrapped to half-wrapped vehicles to rickshaws with hoods until

now, when women ride in open rickshaws. This increasing visibility may indi-

cate women’s growing social liberation and empowerment (see figures 1–3).

Huq and Rashid37 note that only 6.8 percent of passengers depend on mo-

torized vehicles while Mannan and Karim indicate that “women make an

average of 2.21 trips compared to 2.76 for males per day by rickshaw.”38 Sul-

tana39 and Shefali40 state that middle-class women are highly dependent on

rickshaws for their intra urban mobility and about half of women’s trips are

on cycle rickshaws. The Dhaka Transport Coordination Authority (DTCA)

indicated that city dwellers make about 25 million daily trips; rickshaw use

comprises 7 million within this total number of trips.41

Over time the rickshaw design has also undergone transformation to ca-

ter for different kinds of needs for low to middle income people. Rickshaws

may be turned into open vans so they can carry more people as well as being

able to carry different kinds of materials through the narrow lanes. Covered

rickshaw vans have been introduced to carry young children to schools from

or into areas where buses cannot enter because of narrow roads. Such school

vans save time for many women who normally accompany their children to

school.

To make the transport system more efficient, the Bangladesh government

with the help of the World Bank initiated a project entitled “The Dhaka Urban

Transport Project” (DUTP). To allow faster movement of motorized vehicles

the Dhaka City Corporation has imposed a ban on non-motorized vehicles

like rickshaws on major roads as these vehicles were thought to be the main

reason of congestion. But counter arguments also exist: some researchers

argue that this project has failed to capture the differential impacts of vari-

ous transports on men and women. Zohir suggests that gender issues have

not been mainstreamed in the strategies to meet the specific problems of

women.42 The banning of rickshaws has seriously affected the mobility pat-

terns of city residents, particularly middle-class women who rely largely on

rickshaws for their transport. The ban has not only increased journey times as

rickshaws have to take alternative routes through secondary roads and lanes

but has also increased the discomfort associated with the journey because

of the rough conditions of such lanes. The longer routes have also increased

the rickshaw fares. Khandoker and Rouse argue that “rickshaws provided af-

86 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Figures 1–3: Patterns

of rickshaw riding.

Photos: authors.

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 87

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

fordable means of transport for many middle and lower income people. The

rickshaw ban has resulted in many journeys being made either impracticable

or very lengthy along congested small streets, so some pedestrians have been

forced either to walk or catch buses.”43 To provide alternative transportation,

the BRTC has introduced a small number of “women only buses” on certain

routes. However, many women are not able to access these buses, due to the

infrequent service and erratic time schedule. As such, women have to depend

largely on cycle rickshaws for their mobility.

Given this background, this empirical study focuses on the travel behavior

of middle-class women in Dhaka, looking at their preferred mode of trans-

port; the accompanying advantage and disadvantages of forms of transport;

and their perceptions of the ban on rickshaws from the city streets.

The Method and Findings of the Research Study

Our study is mainly based on a field survey conducted in December 2012.

For gathering primary data, a questionnaire was developed with twenty-eight

indicators having both structured and open-ended questions including costs

of transport and travel behavior during peak and off-peak times as well as sea-

sonal variability. The questionnaire also captured the demographic charac-

teristics of the respondents. Some narratives were collected to substantiate

the study.

Six thanas situated within the Dhaka metropolitan area and in neighbor-

hoods with a large concentration of middle-class residents were selected

randomly for the survey. Three of these (North Shahjahanpur, Khilgaon and

Ramna) are from Dhaka South City Corporation and three (Sher e Bangla na-

gar, Tejgaon and Uttara) are from Dhaka North City Corporation (See Figure

4). From each thana twenty-five samples were collected; the total sample size

was 150. Primary data was collected using a purposive sampling method to

fulfill the objectives. The respondents were selected randomly but attention

was given to all age groups and varied educational backgrounds.

The term “middle class” is critical to the study; it is widely used around the

world and it means different things to different people in different places. In-

deed, definitions may change over time as ongoing debates about the emer-

gence and role of the middle class in society indicate. For example, Roberts

has argued that the middle class represents a significant break in the class

structure both subjectively and objectively.44 Abercrombie and Urry define

the middle class as those “who stand in the middle between the workers on

one side and the capitalists and landed proprietors on the other side.”45 In

Bangladesh, the middle class has been identified by Rajat Sanyal as the “intel-

lectually advanced section of a social group. This group however was not ex-

clusively urban in origin and a substantial section of them lived in villages or

88 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

Figure 4: Location of study areas (the straight line denotes the border

between the south and north city corporation of Dhaka City).

Source: Field survey, December 2012

semi urban areas.”46 Sanyal goes on to describe how the middle class “tended

to converge in the urban areas to get suitable education and jobs.”47

Homi Kharas, in a working paper for the OECD Development Center, notes

that “middle class” is an “ambiguous social classification, broadly reflecting

the ability to lead a comfortable life.”48 In the absence of any formal definition

in Bangladesh it is difficult to place people in an income or economic class.

Considering the existing situation, monthly expenditure was taken as the in-

dicator of economic class in this study. The families with monthly expenditure

between 10,000 to 50,000 taka are considered as middle-class families for this

study, which aims to identify the travel pattern of women’s mode of trans-

port in Dhaka City. To complement this definition, we might also consider

the work of Kamal Siddique and his colleagues, whose longitudinal studies of

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 89

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

Dhaka suggest that continued rural migration into the city may have eroded

traditional middle-class signifiers such as higher education, professional em-

ployment and urban culture.49

Among the 150 respondents, a high proportion (42 percent) was young, be-

longing to the 16–25 age group. About 19 percent of the respondents belonged

to the 26–35 age group and some 7 percent were below 15 years of age. The

proportion of the middle-aged group (46–55 years) was about 5 percent while

only 4 percent of the women travelers were of ages between 55 and 75 years.

In terms of literacy about 18 percent were graduates and 3 percent had

post graduate degrees. Over a quarter (27 percent) of the respondents had

education up to higher secondary and another 25 percent had some second-

ary level of education. About 19 percent had primary education and some 7

percent had no formal education or could sign their names only. About half

(50.67 percent) of the respondents were married and 45.33 percent were un-

married. Some 2.67 percent of respondents were widows and 1.33 percent

were divorced.

Respondents’ expenditure ranged between 10,000 to over 50,000 taka per

month. The proportion of monthly expenditure for 24 percent of respondents

was less than 10,000–20,000 taka followed by 34 percent spending 20,000–

30,000 taka per month. Nearly a fifth of respondents, 19 percent of house-

holds, indicate they spend 30,000–40,000 taka and 10 percent spend up to

50,000 taka per month. Monthly expenditure exceeding 50,000 taka was noted

for 12 percent of respondents.

Responses to the survey indicate that while many middle-class women

would prefer to travel by bus for its low fare and speed, only about 1 percent

use the bus as their main mode of transport. The majority of women use the

rickshaw, either on its own or in combination with other forms of transport.

Thus, the main mode of transport for short-distance travel is still the rickshaw

(even for a walking distance). About 52 percent of the study population said

the rickshaw is their main mode of transport and about 33 percent used a

combination of rickshaw and bus as their main mode of transport. The auto

rickshaw (known as CNG) is used by 3 percent of respondents while 10 per-

cent use both CNG and cycle rickshaw as their main travel mode. Only 2 per-

cent use a private car.

Women in the city make trips for different purposes although most trips are

classified by a single main purpose; for example, travelling to one’s workplace,

to an educational institution, or to a healthcare center. As shown in Table 2,

22 percent of all trips by rickshaw were undertaken for attending educational

institutions. For the remaining women, the breakdown is as follows: some 18

percent of women use rickshaws to travel for social visits; 15 percent for ac-

companying children to schools; about 14 percent for household shopping;

11 percent for recreation or entertainment; and 11 percent for going to their

place of work.

90 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

Table 2: Respondents’ purpose for travel

North Dhaka City South Dhaka City

Corporation Corporation Total

Types of Purpose Number Percentage Number Percentage Number Percentage

Going to place of 17 9.14 21 13.29 38 11.05

work

Attending 30 16.13 46 29.11 76 22.10

educational

institution

Accompanying 31 16.67 22 13.92 53 15.41

children to school

Household shopping 30 16.13 18 11.39 48 13.95

Social visit 41 22.04 21 13.29 62 18.02

Visiting doctor, 18 9.68 10 6.33 28 8.14

health center or

hospital

For recreation or 19 10.22 20 12.67 39 11.33

entertainment

Total 186* 100 158 100 344* 100

Source: Field survey, December 2012; *multiple responses recorded

There is no road or lane where rickshaws are not found in Dhaka. Survey find-

ings reveal that 27 percent use a rickshaw for its door-to-door facility, while

23 percent of respondents use a rickshaw for its easy availability within their

area of residence. The low cost of rickshaw travel over other vehicles for short

distances was the reason given by 20 percent of respondents. A further 17 per-

cent use rickshaws because they are suitable for riding in a narrow street or

lane. Thirteen percent, mostly educated or student respondents, chose rick-

shaws because they were environmentally friendly and comfortable vehicles.

Rickshaws are used mainly for short-distance trips where speed is not a

significant factor. The present survey found that 49 percent or respondents

travel for 1–3 km by rickshaw while 23 percent use rickshaws for distances of

less than 1 km. A fifth of women surveyed (20 percent) travel 3–6 km while a

very small number, only 1 percent travel 12–15 km. However, these trips are

influenced more by the road and daily weather conditions than the distance.

As for the frequency of daily rickshaw trips, 59 percent of respondents use

rickshaws two to three times per day, while 27 percent utilize the vehicles

three to five times, 9 percent ride only once a day and 5 percent of respon-

dents travel by rickshaw more than five to seven times a day. No respondents

reported using rickshaws more than seven times a day. The following narra-

tive, from an interview with Rahela Begum (a 42-year-old housewife), illus-

trates how respondents typically use a rickshaw for multiple trips during one

day: “I accompany my daughter to her school by a rickshaw and take another

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 91

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

rickshaw from her school to do daily kitchen market; I take another rickshaw

to come back home from the market. After cooking lunch for the family I shall

go to pick up my daughter from her school by a rickshaw; I make about six

to eight trips by rickshaw per day.” As most rickshaw trips are over short dis-

tances, only very rarely will it take more than 90 minutes to reach a particular

destination. This study noted that 40 percent of women spend 15–30 minutes

on a single rickshaw ride. Twenty-eight percent may spend 30–45 minutes on

a single trip, while the longest travel time spent was 90 minutes. Only 5 per-

cent of respondents travel for 75 to 90 minutes a day on rickshaw. However,

the time spent depends on distance to destination, road congestion, and the

time of day.

Expenditure on rickshaw travel varied among respondents because they

live in different areas of the city and have different reasons for travel. Other

factors relate to demand by other travelers (potential sharing of costs) and the

time of the journey. The study findings suggest that only 3 percent of the re-

spondents spend less than 20 taka per day while a little over 25 percent spend

20–40 taka per day. A more significant amount, 60–80 taka per day, is spent by

22 percent of respondents, while 13 percent spend 80–100 taka per day (see

Table 3). Overall, the average daily expenditure by women travelers is about

15 taka. However, the expenditure increases in unusual circumstances such

as rough weather or when traffic is disrupted in the city.

Table 3: Daily expenditure on rickshaws

Amount (in taka) Number Percentage

Less Than 20 taka 5 3.33

20–40 taka 38 25.33

40–60 taka 33 22.00

60–80 taka 16 10.67

80–100 taka 20 13.33

100–120 taka 19 12.67

120–140 taka 14 9.34

140–160 taka 5 3.33

More than 200 taka 0 0

Total 150 100

Source: Field survey, December 2012

Rickshaws are generally available at all times in most roads except the major

arterial roads of the city. Peak hour of rickshaw demand is from 6 a.m. to 10

a.m. and off-peak times are after 12 p.m. However, the traveler’s purpose and

travel time are important factors that contribute to peak and off-peak demand.

About 20–26 percent of the respondents make rickshaw journeys between

6 a.m. and 10 a.m. while 19 percent make their journeys between 4 p.m. and

92 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

6 p.m. The off-peak hour for women starts from about 7 p.m. onwards when

they remain busy with household work or rest. Farhana Sultana, a banker who

lives about 15 kilometers away from her office, provides us with a glimpse of

the importance of the rickshaw to women travelers.

Sultana uses a combination of vehicles to go to her office. She rides a rick-

shaw to connect to the office bus and comes back in the same manner, spend-

ing 30 minutes on the journey. Sultana observes, “On a strike day when office

bus does not operate and other buses are scarce, rickshaw is the main trans-

port for me to go to office although it takes a long time and [I] have to pay

more fare for travelling.”

The Respondents’ Perceptions of Rickshaw Travel

Most of the respondents prefer the rickshaw because it is the only mode of

transport that can be used for door-to-door service, it is always available and

has an affordable fare for short distances for middle-class families. Some re-

spondents also perceive the rickshaw as a comfortable and environmentally

friendly vehicle, which can give riders privacy, safety and accessibility in nar-

row lanes (see Table 4). It is an important vehicle for making journeys from

the doorstep regardless of possible adverse conditions, including rainy days,

poor road conditions or political strikes.

Table 4: Reasons for using rickshaws as main transport (multiple responses)

Types of reason Number Percentage

Low fare (for short distance) 67 20.49

Environment friendly 41 12.54

Comfortable 40 12.23

Safe 17 5.20

Maintain privacy 6 1.83

Always available 75 22.94

Takes less time to reach the destination 27 8.26

(in some areas)

Easily accessible to narrow lanes 54 16.51

Total 327 100

Source: Field survey, December 2012

Although respondents to our survey indicated their reliance on the rickshaw,

they also expressed concerns about using these vehicles for their daily mo-

bility. Our study found that 29 percent of respondents felt that travelling in a

rickshaw is not safe at all times. Additionally, 24 percent of respondents said

that it is a very risky form of transport on isolated roads and 13 percent of

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 93

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

women are scared about potential accidents. Other concerns about rickshaw

travel came from 3 percent of respondents who said there is less space for

families; 7 percent said that rickshaws are not accessible on major roads; and

4 percent of respondents said the rickshaw fare is high compared to other mo-

torized vehicles such as buses.

According to the respondents their travel pattern by rickshaw varies with

the season and may be affected by seasonal weather patterns: 6 percent of

respondents indicated that rickshaw travel was not suitable in seasonally ad-

verse weather conditions. Among the respondents 30 percent of women travel

more by rickshaw in spring (February to April) and 16 percent travel more in

autumn (August to October) as the nicer weather is a factor. However, there is

not much variation in rickshaw travel in summer (April to June), the monsoon

season (June to August), in foggy weather (October to December) or in the

winter (December to February) season due to limited choice of transport and

the necessities of life.

Bangladesh is a disaster-prone country and consequently rickshaw travel-

ers may face a range of adverse weather conditions in different seasons. This

study noted that 59 percent of women faced various kinds of problems using

rickshaws during extreme rain, storms, or flooding. During these periods 33

percent of respondents use other transport such as auto rickshaws, 21 percent

use buses, 20 percent avoid going out other than for emergencies, 4 percent

walk and only 5 percent use a private car. To mitigate the problems the re-

spondents carry umbrellas and use synthetic clothing and waterproof shoes

to avoid the dirt and water associated with travelling in a rickshaw. During

these periods, the cost of travel escalates and respondents report that they

have to bear these extra costs. The average extra expense is about 500 taka

per month but some women may pay up to an extra 1,000 taka per month.

Women travelers also remain anxious about their personal security and are

concerned about falling victim to different types of crimes and accidents

while riding a rickshaw. They may be fearful of muggings and feel unsafe on

lonely roads, particularly after dark. They also feel insecure in rough roads

with pot holes that may cause accidents or injuries from falling. Sometimes,

though very rarely, the rickshaw puller himself can abuse or assault a woman

passenger.

Conclusion

As our study shows, middle-class women in Dhaka City are reliant on the rick-

shaw for their daily mobility. Thus, government action to ban or restrict rick-

shaw travel on major arterial roads in the city area also has a major impact on

women travelers. The perception of the study population in our survey reveals

that the respondents agree that the low speed of the rickshaw may contribute

94 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

to traffic congestion in the fast-moving motorized roads. However, the study

also noted that 56 percent of the respondents do not support the banning of

rickshaws from the main roads. The analysis is complicated by a further 44

percent of respondents who support withdrawal of rickshaws from the main

roads because of the added dangers of rickshaw rides along main roads with

fast-moving motorized transport. The chances of accidents increase when

the rickshaw pullers are new to the city. These respondents would prefer a

separate rickshaw lane at some major crossings so that the riders do not have

to change rickshaws to reach their destination on the other side of the main

roads.

When asked how a total ban on rickshaws in the city would affect middle-

class women, a large majority of the respondents agreed that “it will be disas-

trous and impossible to live without rickshaws in the city:” the rickshaw is the

main vehicle for women’s daily mobility and the effect of the ban will be felt

in every sector of life. The travel cost will be high and the frequency of travel

will be replaced by longer waiting periods. Orna, a student at Dhaka Univer-

sity, illustrates many women’s concerns in her response: “It is impossible to

move in the city without rickshaw. Many like me who not only study but are

also involved in outdoor activities totally depend on rickshaw. Two or three of

us share the fare for going out to save money. The rickshaw ban has seriously

affected us as we have to break our journey in different crossings and change

rickshaw and pay extra fare.”

Orna’s observation supports the general findings of our study. The rick-

shaw still appears to be the prime mode of transport for middle-income

families and women in particular. The increasing economic pressure and ne-

cessities of life has brought increasing number of middle-class women out of

their homes and the proportion of working women has also increased sub-

stantially over the years—all of these women are heavily dependent on all

kinds of transport, but especially the rickshaw. Although public and private

buses have emerged as the cheapest mode of transport in Dhaka, rickshaws

are the most popular mode of transport and dominate the streets, particularly

the lanes and bi-lanes. Transport choices vary significantly depending on lo-

cation and other socio-demographic factors. Research into these choices, and

travel behavior in general, needs to continue to expand our understanding of

how urban mobility affects women in Bangladesh. While the rickshaw ban

has many supporters, it also has serious implications on women’s mobility in

a fast-growing mega-city like Dhaka.

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain is Professor of Geography and Environment at the

University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. She received her M.Sc. from the London

School of Economics and Political Science and her Ph.D. from the School of

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 95

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

Oriental and African Studies of the University of London, U.K. Her research

interests include gender, migration, poverty, and environment and disaster

studies. She has over thirty-eight publications in local and international jour-

nals (including book chapters) and has written two books and contributed

to three atlases. Address: Department of Geography and Environment, Kazi

Motahar Hossain Bhaban, University of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh.

E-mail: shuqhussain@gmail.com

Umme Habiba is a research officer at the Disaster Research Training and

Management Centre, University of Dhaka. She received her M.S. in Geog-

raphy from the University of Dhaka and is currently a Ph.D. researcher at

the Department of Geography and Environment, University of Dhaka. She is

the co-author of “Gender and Food Security in Bangladesh: A Geographical

Perspective,” Oriental Geographer, 53, Nos. 1&2 (2009): 41–54. Address:

Disaster Research Training and Management Centre, Room No. 241, Depart-

ment of Geography and Environment, Kazi Motahar Hossain Bhaban, Univer-

sity of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh. E-mail: uhabiba2006@yahoo.com

Notes

1. The authors deeply appreciate the editorial corrections done by Dr Deborah

Breen, Boston University.

2. Md. Shafiqul Mannan and Md. Masud Karim, “Current State of the Mobility of

the Urban Dwellers in Greater Dhaka” (paper presented at the annual confer-

ence and exhibition of Air and Waste Management Association, Orlando, Florida,

U.S.A., June 24–28, 2001).

3. Salma Choudry Zohir, “Integrating Gender into World Bank Financed Transport

Programs: Case Study of Bangladesh,” Report prepared for Dhaka Urban Trans-

port Project (2003): http://www4.worldbank.org/afr/ssatp/Resources/HTML/

Gender-RG/Source%20%20documents/case%20studies/ICNET%20Case%20Stu

dies%20for%20WB/CSICN5%20BangladeshThirdRural.pdf (last accessed on 26

October 2013; this applies to all following website references).

4. Tim Cresswell, “Mobilities I: Catching Up,” Progress in Human Geography 35 no. 4

(2010): 550–558, esp. 552.

5. Cresswell, “Mobilities I,” 551.

6. Ibid., 552.

7. Salma Islam, “Middle-income Women in Dhaka City: Gender and Activity Space,”

Durham theses, Durham University (1995), 7. Available at Durham E-Theses On-

line: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5235/

8. Astrid Marxen, “Negotiating Gender: Changing Lifestyles of Female Students

in Dhaka,” University of Bielefeld, Germany (n.d.): www.uni bielefeld.de/tdrc/

downloads/lefo_marxen.pdf

96 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

Gendered Experiences of Mobility

9. Mohammad Niaz Asadullah and Zaki Wahhaj, “Going to School in Purdah: Fe-

male Schooling, Mobility Norms and Madrasas in Bangladesh,” BRAC Research

and Evaluation Division, Research Monograph Series No. 57, Dhaka, Bangladesh

(January 2013): http://research.brac.net/srch_dtls.php?tid=747

10. Pratima Paul-Majumder and Masuda Khatoon Shefali, Examining Gender Dimen-

sions of Transportation in Dhaka Metropolitan Area (Dhaka: Nari Uddug Kendra,

1997), cited in Deike Peter, “Gender and Transport in Less Developed Countries:

A Background Paper in Preparation for CSD-9,” Gender Perspectives for Earth

Summit 2002: Energy, Transport, Information for Decision-making, Berlin, Ger-

many (January 2001).

11. Kamal Siddique et al., Social Formation in Dhaka, 1985-2005 A Longitudinal

Study of Society in a Third-world Megacity (Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing,

2010), 19.

12. Islam, “Middle-income Women in Dhaka City,” 10.

13. Siddique et al., Social Formation in Dhaka, 11, 3.

14. Islam, “Middle-income Women in Dhaka City,” 31.

15. Ibid., 30; and Rangalal Sen, “The Changing Middle Class of Dhaka City and Its

Impact on Bangladesh Society” (paper presented to the Asiatic Society of Bangla-

desh, June, 2008).

16. Thana is the Urdu word for police station; it generally refers to the administrative

area controlled by a local police station.

17. Siddique et al., Social Formation in Dhaka, 11.

18. Ibid., 64.

19. Ibid., 80.

20. Mannan and Karim, “Current State of the Mobility of the Urban Dwellers in

Greater Dhaka.”

21. World Bank, “Bangladesh: Dhaka Urban Transport Project. Mid-term Review

Mission”: http://go.worldbank.org/IIUFI3L6A0

22. Siddique et al., Social Formation in Dhaka, 3.

23. Ibid., 11.

24. Zohir, “Integrating Gender,” 3.

25. Ibid., 6.

26. Ibid., 10.

27. A.T.M. Zahurul Huq, “Transport Planning for Dhaka City”, in DHAKA Past Pres-

ent and Future, ed. Sharif Uddin Ahmed (Dhaka: The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh,

1991), 464–481.

28. Zohir, “Integrating Gender,” 3.

29. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Yearbook of Bangladesh (Government

of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2011).

30. Khaled Mahmud, Khonika Gope and Syed Mustafizur Rahman Chowdhury,

“Possible Causes and solutions of Traffic Jam and Their Impact on the Economy

of Dhaka City,” Journal of Management and Sustainability 2 no. 2 (2012): 112–

135.

31. Mahmud, Gope and Chowdhury, “Possible Causes,” 30.

32. Maruf Hossain and Yusak O. Susilo, “The Exploration of Rickshaw Usage Pattern

and Its Social Impact in Dhaka City, Bangladesh,” Transportation Research Record

2239 (2011), 74–83.

Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013 • 97

Shahnaz Huq-Hussain and Umme Habiba

33. Rob Gallagher, The Rickshaws of Bangladesh (Dhaka: The University Press, 1992),

25.

34. Salim Rashid, “The Rickshaw Industry of Dhaka,” Preliminary Findings, Research

Report 51 (Dhaka: Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, June 1986), 2.

35. National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh: www.banglapedia.org

36. A.T.M. Nurul Amin, “Dhaka’s Informal Sector and Its Role in the Transforma-

tion of Bangladesh Economy”, in DHAKA Past Present and Future, ed. Sharif Uddin

Ahmed (Dhaka: The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, 1991), 446–470, here: 455.

37. Ziaush Shams M.M. Huq and Touhida Rashid, “Rickshaw as a Viable Mode of

Transport in Dhaka City” Oriental Geographer 48 (2004), 58–72, here: 61.

38. Mannan and Karim, “Current State of the Mobility of the Urban Dwellers in

Greater Dhaka,” 2.

39. Sayeda Rabeya Sultana, “Accompanying Children to Schools of Dhaka by Parents

and Total Time Spent: A Behavioral Geographical Analysis” (unpublished M.S.

diss., Department of Geography and Environment, University of Dhaka, 1996).

40. Mashuda Khatum Shefali, “Study on Gender Dimension in Dhaka Urban Trans-

port Project,” Report submitted to the World Bank (2000), http://siteresources

.worldbank.org/INTGENDERTRANSPORT/Resources/bangurbantransport.pdf

41. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, “Dhaka Transport Coordi-

nation Authority (DTCA),” http://www.dtcb.gov.bd

42. Zohir, “Integrating Gender,” 3.

43. Nasrin Khandoker and Jonathan Rouse, “Urban Development and Livelihoods of

the Poor in Dhaka” (paper presented at the 30th Water Engineering and Develop-

ment Center International Conference, Vientiane, Lao PDR, October 2004), www

.dfid.gov.uk/r4d/PDF/Outputs/Urbanisation/R8176-Dhaka.pdf

44. Kenneth Roberts, The Fragmentary Class Structure (London: Heinemann Educa-

tional, 1977).

45. Nicholas Abercrombie and John Urry, Capital, Labour and the Middle Classes:

Controversies in Sociology (London: G. Allen and Unwin, 1983), 50.

46. Rajat Sanyal, “Protiva and Shikha: Two Faces of Literary Culture of Early 20th

Century Dhaka,” in The Freedom of Intellect Movement (Buddhir Mukti Andolan)

in Bengali Muslim Thought, 1926–1938, ed. Shahadat H. Khan (Lewiston, New

York: The Edward Mellen Press, 2007), 287–304.

47. Ibid.

48. Homi Kharas, “The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries,” OECD

Working Paper No. 285, OECD Development Centre, January 2010: 7.

49. Siddique et al., Social Formation in Dhaka, 11.

98 • Transfers • Volume 3 Issue 3 • Winter 2013

You might also like

- Understanding How Women Travel Full ReportDocument168 pagesUnderstanding How Women Travel Full ReportMetro Los Angeles100% (1)

- A Society of Young Women: Opportunities of Place, Power, and Reform in Saudi ArabiaFrom EverandA Society of Young Women: Opportunities of Place, Power, and Reform in Saudi ArabiaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Qatari Women Between Tribalism and Modernity - Hessa Al-MuhannadiDocument92 pagesThe Role of Qatari Women Between Tribalism and Modernity - Hessa Al-MuhannadiEsraa AJ100% (1)

- Legal Notice SampleDocument5 pagesLegal Notice SampleIzaz Arefin100% (1)

- Resume of Shakura AkterDocument12 pagesResume of Shakura AkterMuhammad Ali Imam MahadiNo ratings yet

- Exporter List PDFDocument178 pagesExporter List PDFSaifullah Sheraji80% (5)

- Devising Gender Responsive Transport Policies in South AsiaDocument19 pagesDevising Gender Responsive Transport Policies in South AsiajaysonNo ratings yet

- Post-Modernist Rift and The Role of Feminism in Saudi ArabiaDocument16 pagesPost-Modernist Rift and The Role of Feminism in Saudi ArabiaHumza FarooqNo ratings yet

- Azad Foundation: Making Delhi Safer: Source: SABRE Awards, Gold, South Asia, 2020Document7 pagesAzad Foundation: Making Delhi Safer: Source: SABRE Awards, Gold, South Asia, 2020Ayusha BandiwdekarNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Social Media and Empowerment in The Tourism Sector For Decision Making: A Case Study On Solo Female Travelers in Delhi (India)Document33 pagesDissertation Social Media and Empowerment in The Tourism Sector For Decision Making: A Case Study On Solo Female Travelers in Delhi (India)Rabia KashifNo ratings yet

- Gender Urbanism & Feminist Town PlanningDocument10 pagesGender Urbanism & Feminist Town PlanningCharu PawarNo ratings yet

- City of Men: Masculinities and Everyday Morality on Public TransportFrom EverandCity of Men: Masculinities and Everyday Morality on Public TransportNo ratings yet

- Bangladeshi Women's Experiences ofDocument27 pagesBangladeshi Women's Experiences ofAshok KumarNo ratings yet

- AhonaDocument4 pagesAhonaAsif ANo ratings yet

- Research Question Option 1: ContextDocument2 pagesResearch Question Option 1: ContextAnushka KelkarNo ratings yet

- Mobility & Empowerment: Formative UnderstandingDocument8 pagesMobility & Empowerment: Formative Understandingshadab0123No ratings yet

- Gender and TransportationDocument7 pagesGender and Transportationsuranjanac100% (1)

- 20130722133425Document16 pages20130722133425Mohammad MHNo ratings yet

- Raita Puro 2016Document16 pagesRaita Puro 2016Enamul Hoque TauheedNo ratings yet

- A Study On Women Safety in Public Transport in Lucknow by Pooja ShuklaDocument94 pagesA Study On Women Safety in Public Transport in Lucknow by Pooja ShuklaTahir HussainNo ratings yet

- School of Hospitality, Tourism and Events, Faculty of Social Sciences and Leisure Management, Taylor's University, MalaysiaDocument20 pagesSchool of Hospitality, Tourism and Events, Faculty of Social Sciences and Leisure Management, Taylor's University, MalaysiaBaseerat KhanNo ratings yet

- Education 3 2 3 - 230110 - 115124Document5 pagesEducation 3 2 3 - 230110 - 115124nurul shafifah bt ismailNo ratings yet

- The Interface Between Tradition and Modernity in Naga Society Plagirism CheckingDocument25 pagesThe Interface Between Tradition and Modernity in Naga Society Plagirism CheckingjohnNo ratings yet

- The Women's Movement in Bangladesh: A Short History and Current DebatesDocument30 pagesThe Women's Movement in Bangladesh: A Short History and Current DebatesSrty100% (1)

- Female Taxi Drivers - PakistanDocument3 pagesFemale Taxi Drivers - Pakistanapi-488178103No ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTD., Oxfam GB Development in PracticeDocument16 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTD., Oxfam GB Development in PracticeShohanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Original Irp - MCMCDocument42 pagesOriginal Irp - MCMCNaushad Ahmad100% (1)

- Gender Differences in Commuting Among "Other Workers" in Urban IndiaDocument8 pagesGender Differences in Commuting Among "Other Workers" in Urban IndiaDhruvaditya JainNo ratings yet

- Alainna LiloiaDocument24 pagesAlainna LiloiaAlaa AlobaidNo ratings yet

- Women in Tourism BaliDocument24 pagesWomen in Tourism BaliEndah0% (1)

- Reading 6 SoverigntyDocument48 pagesReading 6 SoverigntyHarry StylesNo ratings yet

- The Role of Women in Chakma CommunityDocument10 pagesThe Role of Women in Chakma CommunityMohammad Boby Sabur100% (1)

- Dhakaiyas GentrificationDocument14 pagesDhakaiyas Gentrificationtarikul islamNo ratings yet

- CM L 1 030115 Bhoomika JoshiDocument5 pagesCM L 1 030115 Bhoomika JoshiAshwani RanaNo ratings yet

- 08 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument17 pages08 - Chapter 2 PDFcharan9015572821No ratings yet

- Article ReviewDocument5 pagesArticle Reviewputri tariza sNo ratings yet

- Private Space in Public Transport: Locating Gender in The Delhi MetroDocument4 pagesPrivate Space in Public Transport: Locating Gender in The Delhi Metrojoejoe3697No ratings yet

- Mobility Aspirations and Indigenous Belonging Among Chakma Students in DhakaDocument17 pagesMobility Aspirations and Indigenous Belonging Among Chakma Students in DhakaEnamul Hoque TauheedNo ratings yet

- Love Marriage or Arranged Marriage Choice Rights and Empowerment For Educated Muslim Women From Rural and Low Income Pakistani Communities PDFDocument18 pagesLove Marriage or Arranged Marriage Choice Rights and Empowerment For Educated Muslim Women From Rural and Low Income Pakistani Communities PDFminaNo ratings yet

- Changing Gender RelationsDocument23 pagesChanging Gender Relationsl_hakim87No ratings yet

- Transforming Faith by Sadaf AhmadDocument3 pagesTransforming Faith by Sadaf AhmadfaisalrehmanchannaNo ratings yet

- 07 P Is There SexismDocument15 pages07 P Is There SexismJOURNAL OF ISLAMIC THOUGHT AND CIVILIZATIONNo ratings yet

- Icphr: Title Women and Transport in Countries DevelopingDocument22 pagesIcphr: Title Women and Transport in Countries DevelopingDicky Purnama AjiNo ratings yet

- Confrontation and Compromise Middle-Class Matchmaking in Twenty-First Century South IndiaDocument21 pagesConfrontation and Compromise Middle-Class Matchmaking in Twenty-First Century South IndiakousikNo ratings yet

- The Moving City: Scenes from the Delhi Metro and the Social Life of InfrastructureFrom EverandThe Moving City: Scenes from the Delhi Metro and the Social Life of InfrastructureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Cin PosterDocument1 pageCin PosterBirmingham Summer School 2012No ratings yet

- Bangladesh Institute of Development StudiesDocument20 pagesBangladesh Institute of Development StudiesShohanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Exploring Travel Characteristics and Factors Affecting The Degree of Willingness of SeniorsDocument8 pagesExploring Travel Characteristics and Factors Affecting The Degree of Willingness of SeniorsShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Relevance of Education For Women's EmpowermentDocument23 pagesRelevance of Education For Women's EmpowermentXahid UsmanNo ratings yet

- Ghs 211 Paper 2 - Qatar 3Document6 pagesGhs 211 Paper 2 - Qatar 3api-584013842No ratings yet

- Portrayal of Women in Pakistani MediaDocument15 pagesPortrayal of Women in Pakistani Medialaiba israrNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 182.255.0.242 On Thu, 18 Mar 2021 06:06:24 UTCDocument24 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 182.255.0.242 On Thu, 18 Mar 2021 06:06:24 UTCArca MaidaNo ratings yet

- Sex and Salvation: Imagining the Future in MadagascarFrom EverandSex and Salvation: Imagining the Future in MadagascarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Examining The Demographic and Socio Economic Differentials in Commuting A Review of LiteratureDocument5 pagesExamining The Demographic and Socio Economic Differentials in Commuting A Review of LiteratureEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- 5 Hurdles in Women Deveopment DR Aisha Anees & Muhammad AamirDocument12 pages5 Hurdles in Women Deveopment DR Aisha Anees & Muhammad AamirjunaidyousafNo ratings yet

- David Willmer Women As Participants in The Pakistan MovementDocument18 pagesDavid Willmer Women As Participants in The Pakistan MovementSaira MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Outline For q3 SmallDocument23 pagesOutline For q3 SmallRameen MalikNo ratings yet

- 1993 Urban Rural Ghunghat Chowdhry PDFDocument23 pages1993 Urban Rural Ghunghat Chowdhry PDFBeled Fourth YrNo ratings yet

- The Psycho-Social Impact of The Olympic Winter Games Organization On The Romanian TourismDocument5 pagesThe Psycho-Social Impact of The Olympic Winter Games Organization On The Romanian Tourismkemala firdausiNo ratings yet

- Rural Cultural Economy - Tourism and Social Relations (Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 28, Issue 3) (2001)Document22 pagesRural Cultural Economy - Tourism and Social Relations (Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 28, Issue 3) (2001)kemala firdausiNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Social Impacts of Tourism Research - A New Research Agenda (Tourism Management, Vol. 33, Issue 1) (2012)Document10 pagesRethinking Social Impacts of Tourism Research - A New Research Agenda (Tourism Management, Vol. 33, Issue 1) (2012)kemala firdausiNo ratings yet

- Alternative Tourism and Social Movements (Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 29, Issue 1) (2002)Document20 pagesAlternative Tourism and Social Movements (Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 29, Issue 1) (2002)kemala firdausiNo ratings yet

- Middle-Class Travel Patterns, Predispositions and Attitudes, and Present-Day Transport Policy in Bangkok, ThailandDocument21 pagesMiddle-Class Travel Patterns, Predispositions and Attitudes, and Present-Day Transport Policy in Bangkok, Thailandkemala firdausiNo ratings yet

- No - Busy Travelers - Leisure-Travel Patterns and Meanings in Later Life (World Leisure Journal, Vol. 44, Issue 2) (2002)Document11 pagesNo - Busy Travelers - Leisure-Travel Patterns and Meanings in Later Life (World Leisure Journal, Vol. 44, Issue 2) (2002)kemala firdausiNo ratings yet

- Tourism and The Environment Regional, Economic, Cultural and Policy Issues (Helen Briassoulis, Jan Van Der Straaten (Auth.) Etc.)Document377 pagesTourism and The Environment Regional, Economic, Cultural and Policy Issues (Helen Briassoulis, Jan Van Der Straaten (Auth.) Etc.)kemala firdausiNo ratings yet

- Tutul Final CVDocument2 pagesTutul Final CVNishaNo ratings yet

- List of Cambridge Attached Centres in BangladeshDocument12 pagesList of Cambridge Attached Centres in BangladeshpalashndcNo ratings yet

- Pritam Mitra PDFDocument3 pagesPritam Mitra PDFpmbappaNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2018 19 UPGDCL PDFDocument192 pagesAnnual Report 2018 19 UPGDCL PDFANSNo ratings yet

- 5th 2010 ResultDocument936 pages5th 2010 ResultShopnoPathik AionNo ratings yet

- Asian Paints Brand Presentation.v9 PDFDocument125 pagesAsian Paints Brand Presentation.v9 PDFSamiul Kabir Rokon100% (1)

- Sample CVDocument3 pagesSample CVahamedtouhid899No ratings yet

- A Study On Higher Education in Bangladesh PDFDocument15 pagesA Study On Higher Education in Bangladesh PDFJerin100% (3)

- 孟加拉客戶資料Document23 pages孟加拉客戶資料batsy4evNo ratings yet

- Trade Vis inDocument13 pagesTrade Vis inTaifHossainNo ratings yet

- CV of Tanvir IqbalDocument2 pagesCV of Tanvir IqbalThe-Tanvir IqbalNo ratings yet

- List of Bank and Insurance CompaniesDocument11 pagesList of Bank and Insurance CompaniesThomas HarveyNo ratings yet

- Amex Offers Dining 2022Document21 pagesAmex Offers Dining 2022Mohammad Ashraf UddinNo ratings yet

- Case On Berger Paints Bangladesh LTDDocument12 pagesCase On Berger Paints Bangladesh LTDDanny Martin GonsalvesNo ratings yet

- Apllication For AISD NewDocument3 pagesApllication For AISD NewBazlul KarimNo ratings yet

- CV of Engr. Muhammad Musleh UddinDocument3 pagesCV of Engr. Muhammad Musleh UddinShahed48bdNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of Bangladesh Decision in Mulla Qadir CaseDocument790 pagesSupreme Court of Bangladesh Decision in Mulla Qadir CaseFarhat Abbas DurraniNo ratings yet

- Life in Dhaka City - EssayDocument2 pagesLife in Dhaka City - EssayK. Saykat100% (1)

- SSC (Voc) & Dakhil (Voc) Class-IX Result 2020Document627 pagesSSC (Voc) & Dakhil (Voc) Class-IX Result 2020MITO AKTERNo ratings yet

- Impact of Rural-Urban Migration in BangladeshDocument33 pagesImpact of Rural-Urban Migration in BangladeshKhondker Rawan Hamid91% (11)

- Course Code: GEHE 2301 Course Title: History of Emergence of Bangladesh 3:3CHDocument20 pagesCourse Code: GEHE 2301 Course Title: History of Emergence of Bangladesh 3:3CHAzwad HabibNo ratings yet

- Category List Latest Amar TakaDocument200 pagesCategory List Latest Amar TakaJonayed HossainNo ratings yet

- Bus Services in BangladeshDocument103 pagesBus Services in BangladeshNabendu LodhNo ratings yet

- Formation of National Identity in Bangladesh and Rabindranath TagoreDocument2 pagesFormation of National Identity in Bangladesh and Rabindranath TagorerezaaaronNo ratings yet

- Existing ATM List With Location: SL# Entity Nos. Branch Location District Agrani Bank LTDDocument107 pagesExisting ATM List With Location: SL# Entity Nos. Branch Location District Agrani Bank LTDমান্দা,নওগাঁ - Manda,NaogaonNo ratings yet

- Assignment On FIN211Document18 pagesAssignment On FIN211Muhtasin Monir GemNo ratings yet

- Merged Arch PDFDocument24 pagesMerged Arch PDFatiqurNo ratings yet