Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Positive Impact of ID On Families

Uploaded by

Sylvia PurnomoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Positive Impact of ID On Families

Uploaded by

Sylvia PurnomoCopyright:

Available Formats

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive Impact of Intellectual Disability on Families

Jan Blacher

University of California, Riverside

Bruce L. Baker

University of California, Los Angeles

Abstract

Understanding positive, as well as negative, impact of a child with mental retardation will

lead to a more balanced view of families and disability. In two studies we examined parents’

perceived positive impact of a child with MR/DD. Study 1 involved 282 young adults

with severe mental retardation; Study 2 involved 214 young children with, or without,

developmental delays. In both studies, positive impact was inversely related to behavior

problems. Moreover, positive impact moderated the relationship between behavior prob-

lems and parenting stress. Also, main and moderating effects of positive impact differed

by parent ethnicity. Latina mothers reported higher positive impact than Anglo mothers

did when the child had MR/DD. These findings are discussed in the context of cultural

beliefs.

The idea that a child with mental retardation even a lack of conceptual clarity as to what is

could impact his or her family positively is a rel- meant by positive impact or related terms. We

atively new one. Only in the past decade or two propose three levels at which one could view, and

have researchers considered ‘‘positive impact of assess, the positive impact of a child on his or her

the child’’ worthy of empirical study (Hastings & family. The first is a view that positive impacts

Taunt, 2002; Summers, Behr, & Turnbull, 1989). can be imputed by the absence of negative ones.

By contrast, for over half a century, published re- In this ‘‘low negative’’ view, positive impacts

search has been focused on negative impacts of would be inferred if the parent reported low scores

children with mental retardation on their families on measures of adverse well-being. The second is

(Blacher & Baker, 2002). Although a more bal- that despite their child’s disability, parents expe-

anced view of families and disability is certainly a rience many of the same joys of child-rearing that

conceptual step forward, there is still little well- are experienced by families of children without a

controlled research on positive impact (Helff & disability. In this ‘‘common benefits’’ view, posi-

Glidden, 1998). In the present paper we report on tive impacts would be demonstrated by evidence

two studies of the positive impact of disability, that parents of a child with disabilities report the

assessing families of young children and young same types and extent of positive experiences re-

adults. We examined parents’ perception of both lated to childrearing that are reported by parents

positive and negative impact on the family in re- of children without disabilities. The third is a view

lationship to characteristics of the child (disability that because of the disability the family experi-

status, behavior problems), the parents (mother ences unique benefits not necessarily experienced

vs. father), and the family’s cultural heritage (An- by parents of children without disabilities. In this

glo vs. Latino). ‘‘special benefits’’ view, positive impacts would be

The disability field lacks theoretical models demonstrated by observations of benefits that are

that fully address this idea of positivity. There is not found in families without a child who has a

330 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

disability. These three perspectives often are con- family dynamics, and opportunities to learn new in-

fused in the literature. formation.

The first view of positive impact, low nega- Although reports from such studies have

tive, is reflected in arguments that one way to con- some heuristic value in identifying themes that

ceptualize positive perceptions is by the absence might be special benefits, any conclusions must

of stress, depression, or other forms of negative be tempered not only because of the positive bias

impact (Taunt & Hastings, 2002). To validate this in the way questions have been asked, but also

view, one would need to show that low scores on because, without adequate control groups, we can-

measures of negative impact relate to high scores not know whether these are, indeed, special ben-

on separate measures of positive impact; this rare- efits. It is important to determine whether these

ly has been done. Although such measures are perceived benefits are unique to disability or are

likely to be modestly negatively correlated, par- also reported by parents raising typically devel-

ents may simultaneously report negative and pos- oping children, as well as the extent to which both

itive perceptions. A two-factor model of caregiv- groups reported such benefits. In one of the few

ing appraisal proposed in the gerontology field studies to contrast parents of children with and

(Lawton, Moss, Kleban, Glicksman, & Ravine, without disabilities, Margalit and Ankonina

1991) and further developed with aging parents of (1991) found that parents of children with dis-

adult children with intellectual disabilities (Pruch- abilities exhibited more negative affect but that

no, Patrick, & Burant, 1996) views positive and positive affect did not differ between the groups.

negative emotional states not as polar opposites The conceptual confusion surrounding posi-

but, rather, as partially independent and as having tive impact is increased by two additional domains

different antecedents. In the present studies we considered in the literature. One is the focus in

examined the relationship between a measure of some studies on positive personality dispositions in

positive impact and typical measures of negative the parent, such as optimism, empowerment, per-

impact. ceived competence, self-mastery, or resilience (Has-

The second, common benefits, view has re- tings and Taunt, 2002; Singer & Powers, 1993).

ceived little specific attention, whereas many studies These personal qualities are important to study

have purported to address the third, special benefits because they may buffer the impact of child chal-

view (Hastings & Taunt, 2002; Sandler & Mistretta, lenges on parents’ well-being (Baker, Blacher, &

1998; Stainton & Besser, 1998). Unfortunately, Olsson, 2005). Yet, they do not measure, or even

study methods usually have confused the two views. necessarily reflect, the positive impact of the

For example, Stainton and Besser, through inter- child; indeed, they may be traits that the parent

views with 17 families, asked only the question: possessed before even having children. There is

‘‘What are the positive impacts you feel your son ample nondisability-related literature to suggest

or daughter with an intellectual disability has had that positive ways of thinking can lead to better

on your family?’’ From qualitative analysis of re- mental health outcomes for the individual (Bower

sponses, the authors advanced nine themes (e.g., & Segerstrom, 2004; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Pe-

source of joy and happiness, source of family unity terson, 2005).

and closeness, source of personal growth and The other, and related, view of positive im-

strength). Sandler and Mistretta (1998) administered pact is found in studies that are focused on effec-

a survey to 50 parents of adults with mental retar- tive strategies for coping with childrearing, such

dation and broadly assessed positive attitudes. These as cognitive coping (Turnbull et al., 1993) or ac-

were endorsed by a high percentage of respondents commodation (Gallimore, Hoots, Weisner, Gar-

and clustered in themes of emotional adjustment nier, & Guthrie, 1996). Here, too, these authors

(e.g., confidence, fulfillment), attitudes toward the did not speak directly about how the child posi-

adult child (e.g., feelings of happiness), positive fam- tively impacts the family, although they accentu-

ily impact (e.g., closeness among members), and per- ated family strengths that may contribute to pos-

sonal growth (e.g., compassion). Similarly, Hastings itive outcomes. Several researchers have combined

and Taunt (2002) asked parents to report on the assessments of positive perceptions and coping

positive impact of the child with the disability on strategies. Hastings and his colleagues assessed

the siblings and on the extended family. Parent re- three domains of positive perceptions (Happiness

sponses included having increased sensitivity and and Fulfillment, Strength and Family Closeness,

tolerance, a changed perspective on life, improved Personal Growth and Maturity) of 41 mothers of

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 331

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

children (aged 4 to 19) with intellectual disability an influence on parents’ positive perceptions.

(Hastings, Allen, McDermott, & Still, 2002). All Many researchers have found that behavior and/

three were positively related to the coping strategy or mental health problems relate to parental well-

of reframing. being, including measures of negative impact and

These various perspectives on ‘‘positive’’ parenting stress, depression, and burden (Baker,

come together in more generic coping models, Blacher, Kopp, & Kraemer, 1997; Baxter, Cum-

where ‘‘positive perception’’ is a core component, ming, & Yiolitis, 2000; Hauser-Cram, Warfield,

particularly as applied to physical stress and health Shonkoff, & Krauss, 2001; McIntyre, Blacher, &

outcomes (e.g., women coping with breast cancer; Baker, 2002). In fact, recently investigators have

Taylor, 1983; Taylor, Lerner, Sherman, Sage, & found that the well-established relationship be-

McDowell, 2000) and psychological distress, such tween intellectual disability and adverse parental

as caregiving for partners with AIDS and bereave- well-being can be accounted for almost entirely

ment (Folkman, 1997). In these instances, positive by child behavior problems (Baker, Blacher,

perceptions serve therapeutically as an adaptive Crnic, & Edelbrock, 2002; Baker et al., 2003;

coping mechanism. Floyd & Gallagher, 1997; Floyd & Phillippe,

In sum, the emerging literature on positive ef- 1993). In the present studies we examine the re-

fects is uncoordinated and inconclusive, with lationship of behavioral challenges to parent-per-

varying conceptions of ‘‘positive,’’ bias in the way ceived positive impact of young children and

questions are posed, the absence of nondisabled young adults.

control families, and a focus on mothers only. A At the family level, a key variable is parent

central problem is the shortage of standardized gender. Most researchers examining the impact of

measures of positive impacts. Measures of parent- disability on parents obtained data from mothers

ing stress or negative impact abound, and, from only, giving an incomplete picture. Fathers usually

the first low negative view discussed above, one have different roles in the family as well as differ-

might consider low scores to be positive. How- ent relationships with the child and different op-

ever, in addition to conceptual limitations (as it is portunities to observe the child’s behavior (Phar-

certainly possible to hold both positive and neg- es, 1996). When both parents have been included

ative perceptions simultaneously), there is a draw- in studies of children with disabilities, mothers

back to many of the measures themselves. The have reported more stress than have fathers in

scales primarily used by family-disability research- practically all families (summarized in Hastings,

ers, such as the widely used Questionnaire on Re- Beck, & Hill, 2005; but see Dyson, 1997). Little

sources and Stress QRS (Holroyd, 1985), the is known, however, about positive perceptions of

QRS-short form (Friedrich, Greenberg, & Crnic, mothers and fathers because most reports of pos-

1983), or the Kansas Inventory of Parental Percep- itive perceptions have involved only mothers (e.g.,

tions (Behr, Murphy & Summers, 1992) have a Hastings et al., 2002; Stainton & Besser, 1998;

strong disability focus and are not appropriate for Taunt & Hastings, 2002). However, Hastings,

use with families who have typical children, pre- Beck, and Hill (2005), using the Positive Contri-

cluding comparisons. In the present studies we butions Scale (Behr et al., 1992) with mothers and

used a measure that includes a positive perception fathers of children with intellectual disability,

scale and is not specific to disability, the Family found that mothers reported slightly, though sig-

Impact Questionnaire FIQ (Donenberg & Baker, nificantly, more positive perceptions of their

1993). Thus, in these two studies we could address child.

the common benefits view of positive impact, but, At the cultural level, although family research

due to the nature of our measure, not the special primarily has involved Euro American families,

benefits view. there is developing interest in examining parent-

Parents’ perception of positive impact is likely ing practices and beliefs about disability cross-cul-

to be related to characteristics of the child but also turally (Lynch & Hanson, 2004; Zuniga, 1998).

must be considered within the broader context of For example, investigators have found less per-

the family and the culture. From among the many ceived burden and more satisfaction (i.e., a posi-

child, family, and cultural variables that might in- tive contribution) from providing care to a child

fluence parental perceptions, we focus here on with intellectual disabilities for African American

three. At the child level, behavioral challenges, compared to Caucasian mothers (Valentine,

apart from cognitive disability, are likely to have McDermott, & Anderson, 1998). Some reasons

332 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

for these positive perceptions include the value child and family: preschool and the transition to

attributed to intergenerational family support adulthood.

(Cox, Marshall, Mandleco, & Olsen, 2003) and Five questions were of primary interest. The

the protective factor of spirituality or religious first two relate to the conflicting views of positive

connectedness (Billingsley, 1992; Rogers-Dulan & impact that we have considered. The others relate

Blacher, 1995). Our analysis of culture contrasts to the relationship of salient child, parent, and

the perceptions of parents in the dominant Unit- cultural attributes to expressed positive impact.

ed States culture, Caucasians (herein referred to as First, how do positive impact and negative

Anglos), and the fastest growing cultural group in impact measures relate? If these measures have a

the country, namely, Latinos. Depression symp- strong negative relationship, the ‘‘low negative’’

toms have been found to be high in Latina moth- view of positive impact garners some support.

ers of low-functioning children with disabilities Conversely, if the measures have only a modest

(Blacher, Shapiro, Lopez, Diaz, & Fusco, 1997). relationship, this is supportive of the ‘‘two-factor’’

However, positive impact reported by Latina view, wherein positive and negative perceptions

mothers of young adults in a previous study was are largely independent. Second, do parents of

also high, and equally so regardless of the child’s children with and without disabilities differ on a

diagnosis (i.e., autism, Down syndrome, cerebral measure of positive impact that is not disability-

palsy, undifferentiated mental retardation) (Blach- specific? To the extent that the groups do not dif-

er & McIntyre, 2006). To further our understand- fer, the findings would support the common ben-

ing of positive perceptions of disability, we must efits view that some positive perceptions reported

consider cultural context (Hodapp, Glidden, & by parents of children with disabilities are not spe-

Kaiser, 2005). We designed the studies in the pre- cial but are shared by parents of children without

sent paper to replicate and extend these initial disabilities. Third, does positive impact relate to

findings, contrasting positive perceptions in the extent of child behavioral challenges? We ex-

mothers and fathers of children with and without amined whether positive perceptions also relate to

disability and considering the buffering role of the extent of child and young adult behavior

cultural group on the relationship between behav- problems. Fourth, does positive impact relate to

ior problems and positive impact. parent gender or to cultural origins? In Study 2

In this paper we report on two studies of par- we examined whether mothers and fathers differ

ents’ perceived positive impact of a child with dis- in their perceptions of positive impact, and in

abilities. These studies are focused on positive par- both studies we examined how positive impact is

enting experiences that parents of children with expressed within families of Anglo and Latino or-

mental retardation may share with parents of typ- igins. Fifth, does positive impact moderate the es-

ically developing children. Data were drawn from tablished relationship between child behavior

two samples of families. The first, obtained from problems and parenting stress? Hastings and

the University of California, Riverside Families Taunt (2002) have suggested a functional perspec-

Project, includes 282 young adults with moderate tive of positive perceptions, in that they aid in

to profound mental retardation; the second, from coping with stressors and thus buffer adverse out-

the Collaborative Family Study at Penn State, comes. There is related evidence that the person-

UCLA, and UC, Riverside, includes 214 young ality trait of optimism was a buffer for mothers,

children with mild to moderate developmental de- whereby child behavior problems had the greatest

lays or typical development. Our intent was not negative effect on well-being for mothers who

to provide direct comparison of the two samples were least optimistic (Baker et al., 2005). Thus, we

(the participants were different in age and level of hypothesized that parents low in perceptions of

functioning). Rather, the two contexts provide an positive impact would be more negatively affected

opportunity to examine the robustness of the phe- by child or young adult behavioral challenges

nomenon of positive impact in families who have than parents with higher positive perceptions.

children with mental retardation and to garner in-

formation about the contribution of specific child

STUDY 1: FAMILIES PROJECT

and parent characteristics in assessment of positiv-

ity. These two samples, with overlapping mea- YOUNG ADULTS

sures, afforded us an opportunity to examine pos- Study 1 was focused on three of the aims (1,

itive impact at two critical times in the life of the 3, 5) identified above. First, we considered the low

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 333

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

negative view by examining the relationship be- stitutional Review Board. Table 1 shows selected

tween measures of well-being and positive percep- demographics by sample (Anglo vs. Latino). Ma-

tions. Second, we examined whether mothers’ per- ternal age averaged 49 years (range ⫽ 31 to 70).

ception of positive and negative impact related to Biological mothers were the primary respondents

the degree of young adult behavior and/or mental in 92.2% of families; thus, we refer to parents as

health problems. Third, we examined the main mothers throughout. The majority were married

and moderator effects of positive impact in the (68.6%) and worked outside of the home (63.1%).

relationship between child behavior problems and The Anglo sample was significantly higher than

maternal well-being. the Latina sample on measures of education, in-

come, and health. The majority of the young

adults were male (56.7%) and still attending

Method

school (58.5%). Although most young adults were

Participants still living in the family home (89.8%), signifi-

Participants were mothers of 282 young adults cantly more (though still few) in the Anglo sample

with moderate to profound mental retardation. were living in outside residences; their parents

For the present study, the mean age of the young were still very involved. The young adult demo-

adults was 20.3 years (range ⫽ 16 to 26). There graphics (e.g., age, ambulation, adaptive behavior,

were 150 Anglo and 132 Latina mothers. A sub- maladaptive behavior, and mental health) were

sample of 103 of these mothers participated in the quite similar across the Anglo and Latina samples.

study reported by McIntyre et al. (2002), who re- The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow,

ported on an earlier wave of data collection. All Balla, & Cicchetti, 1984) mean standard scores for

procedures were approved by the University’s In- both samples were about five SDs below the me-

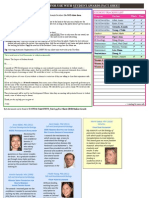

Table 1. Study 1: Family/Mother and Young Adult Characteristics by Sample

Anglo Latino

Characteristic Mean/% Mean/% t/⌾2a

Family/Mother

Mean age in years (SD) 48.5 (5.7) 49.5 (8.1) 1.12

Education (% some college) 76.7 28.8 62.94***

Health (% reported good/excellent) 86.6 53.0 36.51***

Maternal status (% biological) 90.7 93.9 .64

Maternal employment (% employed) 68.0 57.6 2.84

Marital status (% married) 75.3 61.4 5.75*

Family Income (% ⱖ $40,000/year) 73.3 19.7 78.76***

Young adult

Mean age in years 20.4 (2.3) 20.2 (2.8) .70

Gender (% male) 57.3 56.1 .01

Ambulation (% ambulatory) 76.0 75.8 .00

School status (% exited school) 41.3 41.7 .00

Residential status (% out–of–home) 16.0 3.8 10.06**

Mean Adaptive Behavior Standard Score 25.6 (10.4) 24.2 (8.8) 1.19

Mean maladaptive behaviorb ⫺13.2 (10.5) ⫺12.7 (10.9) .38

Mean maladaptive behavior (% mod–high, SIB–R) 21.3 25.2 .39

Mean mental healthc 6.8 (5.1) 7.7 (5.7) 1.38

Mental health (% at-risk)c 33.3 41.9 1.65

Note. Anglo n ⫽ 150, Latino n ⫽ 132)

a

t is used when standard deviations are reported. bScales of Independent Behavior–Revised, General Maladaptive Index.

c

Reiss Screen Total.

*p ⬍ .05. **p ⬍ .01. ***p ⬍ .001.

334 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

dian (100). This was a very low-functioning group The Positive Impact scale has six items en-

of young adults. dorsed on a 0 to 3 scale and one item on a 0 to

6 scale. Thus, the scale score can range from 0 to

24. Each item begins, ‘‘Compared to children,

Procedure

Participants were recruited for an ongoing and parents with children the same age as my

longitudinal study through Southern California child’’ followed by, for example: (a) I enjoy the

Regional Centers, agencies that provide case man- time I spend with my child more; (b) My child

agement services to individuals with mental retar- brings out feelings of happiness and pride more;

dation (see Blacher & McIntyre, 2006, as well as (c) My child makes me feel more energetic; and

McIntyre et al., 2002, for details on recruitment, (d) My child makes me feel more confident as a

informed consent, and interviewer training). Data parent. Internal reliability for mothers in the Fam-

were collected during in-home interviews with ilies Project sample (Study 1) was an alpha of .83.

mothers. All interviews were conducted in the pre- Internal reliabilities in the Collaborative Family

ferred language of the family (English or Spanish); Study sample (Study 2) for mothers and fathers at

most interviewers, and all interviewers for the La- child age 3 years were .81 for both. At 4 years,

tina sample, were bilingual and Latino. Families they were each .86; and at 5 years, .86 and .85,

received honoraria for their participation. respectively. Positive Impact also had moderate to

high stability over time, with Pearson rs ranging

from .60 to .75 across ages 3 to 5 years.

Measures An additional measure of parent well-being

The FIQ (Donenberg & Baker, 1993) is a 50- was the Center for Epidemiological Studies-De-

item measure focused on the child’s impact on pression scale CES-D (Radloff, 1977). This is a

the family compared to the impact other children widely used 20-item self-report of depressive

his/her age have on their families. For use with symptoms. Alpha in the present sample was .90.

parents of young adults, all references to ‘‘chil- The Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised

dren’’ were changed to ‘‘young adults.’’ Parents Problem Behavior Scale SIB-R (Bruininks,

endorse items on a 4-point scale ranging from not Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996) is an

at all to very much. The FIQ was developed to

8-item instrument yielding the General Maladap-

address three limitations shared by most parent

tive Index, with a possible range of ⫹10 to ⫺74.

stress measures used by family researchers. First,

Levels of severity are delineated in the adminis-

many measures are focused on difficult child be-

tration manual as ⫹10 to ⫺10 ⫽ normal; ⫺11 to

haviors or skill deficits and infer parental stress

⫺20 ⫽ marginally serious; ⫺21 to ⫺30 ⫽ moder-

from these rather than asking parents directly

ately serious; ⫺31 to ⫺40 ⫽ serious; ⫺41 and be-

about the impact their child has on them. Second,

low ⫽ very serious (Bruininks et al., 1996). We

most measures are focused exclusively on the neg-

ative impact of the child on the family without have used a score of ⫺21 and lower to indicate a

also assessing the child’s positive impacts. Third, clinical range on this measure (McIntyre et al.,

most stress measures are applicable only to fami- 2002). The manual provides sufficient evidence

lies with children who have mental retardation/ for reliability (e.g., test–retest reliability r ⫽ .86;

developmental disabilities or only to families with Cronbach alpha ⫽ .80) and validity.

typically developing children. The Reiss Screen for Maladaptive Behavior,

There are six scale scores on the FIQ that 2nd ed. (Reiss, 1994) was obtained from 260 of

measure Negative Impact on Feelings About Par- the 282 families. The Reiss Screen is a 38-item

enting, Social Relationships, Finances, Marriage screening tool used to identify mental health

and Siblings, and Positive Impact on Feelings problems in adolescents and adults across the full

About Parenting. In the present study, we utilized range of mental retardation. Items describe dis-

a Negative Impact composite of the first two sub- crete behavior categories with a 3-point response

scales (20 items) as well as the Positive Impact scale of (0) no problem, (1) problem, and (2) major

scale (7 items). The Negative Impact composite, problem. We have used a total score of 9 or above

which has been used in samples with and without to indicate clinically significant risk of mental ill-

mental retardation, has good reliability and valid- ness, as suggested by Reiss (1994). The manual

ity (Baker, Heller, & Henker, 2000; Baker et al., reports adequate total score internal consistency,

2002; Blacher & McIntyre, 2006). alphas ⬎ .70, and sufficient evidence for validity

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 335

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

based on clinical and nonclinical samples (Reiss, Anglo mothers (Ms ⫽ 17.6 and 12.0, respective-

1994). ly), t(267) ⫽ 9.76, p ⬍ .001 (Blacher & McIntyre,

2006). Here, we examined the relationship of

Results young adult behavioral challenges to negative and

positive impact separately for Latina and Anglo

Positive Impact Inferred From Low-Negative mothers. Three levels of young adult behavior and

We first examined the view that positive im- mental health problems were determined from

pact can be inferred from low scores on measures scores on the Reiss Screen and SIB-R. Young

of negative impact or well-being. Positive impact adults in the nonclinical range on both scales (see

correlated inversely with negative impact, r ⫽ Method) received a score of 0 (n ⫽143). Young

⫺.45, p ⬍ .001. To examine this further, we di- adults in the clinical range on either scale received

vided positive impact and negative impact into a score of 1 (n ⫽ 49), and those in the clinical

thirds and compared them in cross-tabs. Of the range on both scales received a score of 2 (n ⫽

87 cases in the lowest third on negative impact, 53). Figure 1 shows FIQ Negative and Positive Im-

only 49% fell into the highest third on positive pact scores by the Behavior Problems/Mental

impact. Thus, although there was a modest cor- Health Index as well as the significance of differ-

relation between positive and negative impact, if ences. One-way ANOVAs showed that negative

only the low third of negative impact were used impact increased significantly with increasing Be-

for determining positive impact, fully half of the havior Problems/Mental Health scores in both the

sample would have been misclassified. Moreover, Anglo and Latina subsamples. Also, positive im-

positive impact was not significantly correlated pact decreased significantly, especially from low

with depression, r ⫽ ⫺.09. to high Behavior Problems/Mental Health scores,

in both the Anglo and Latina subsamples.

Positive Impact and Young Adult Behavioral

Challenges Positive Impact as a Buffer

We previously reported significantly higher We further considered whether perceiving

positive impact scores for Latina mothers than greater positive impact of the young adult would

Figure 1. Study 1: Anglo and Latina mothers’ reports of negative and positive impacts of young adults’

behavior/mental health problem (BPMH).

336 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

moderate, or buffer, the strong relationship be- Conclusions

tween behavior/mental health problems and Study 1 findings indicate that within this sam-

mothers’ well-being. We conducted a regression ple of young adults with moderate to profound

on the FIQ Negative Impact score with the whole mental retardation, mothers’ perceptions of posi-

sample. In Step 1, we entered, as control variables, tive impact were highest when young adults did

the two demographic variables that correlated sig- not have behavior and/or mental health problems

nificantly with negative impact: young adult gen- high enough to be in the clinical range. Moreover,

der and Vineland Standard Score. These account- even after accounting for young adult behavioral

ed for 7.8% of the variance in negative impact. In challenges, mothers with higher perceptions of

Step 2, we entered the Reiss Screen Total score, positive impact reported less stress (main effect).

which accounted for 20.7% additional variance, F Perceptions of positive impact had a somewhat

(change) ⫽ 69.69, p ⬍ .001. In Step 3, we entered greater buffering effect when behavioral challeng-

the Positive Impact score, which accounted for es were high (moderation effect). Although Latina

12.5% additional variance, F (change) ⫽ 50.68, p mothers reported higher positive impact scores

⬍ .001. In Step 4, after converting the Reiss Total than Anglo mothers, positive impact related sim-

and Positive Impact to z scores, we entered the ilarly to young adult behavior and/or mental

product of these two z scores as a test for mod- health problems in both cultural groups.

eration; although this accounted for only 1.3%

additional variance, it was statistically significant,

F (change) ⫽ 5.21, p ⫽ .02. Higher positive im-

STUDY 2: COLLABORATIVE FAMILY

pact somewhat buffered the increase in stress that STUDY YOUNG CHILDREN

accompanies greater young adult mental health In this study we investigated all five aims

problems. This is shown graphically in Figure 2. identified above at a much earlier point in the

We repeated this analysis separately within the family lifespan. In this younger sample, there was

Anglo and Latina subsamples; positive impact ac- a typically developing contrast group, and data

counted for significant additional variance in were obtained from mothers and fathers. First, we

both, but the interaction did not reached signifi- examined the low negative view and by contrast-

cance in either. ing views of parents of children with and without

Figure 2. Study 1. Positive impact as moderator of the relationship between young adult mental disorder

and parenting stress. Square, high; triangle, moderate; and circle, low positive impact.

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 337

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

delay, the common benefits view. Next, we ex- the research center. General selection criteria were

amined whether parents’ perception of positive that the child be between 30 and 40 months of

and negative impact related to child problem be- age and not be diagnosed with autism. Participat-

haviors, to parent gender, and to culture. Finally, ing children were classified as developmentally de-

we examined the main and moderator effects of layed (n ⫽ 82), borderline (n ⫽ 10), or nondelayed

positive impact in the relationship between child (n ⫽ 122). Delayed group families were recruited

behavior problems and parent well-being for both primarily through community agencies that serve

mothers and fathers. persons with developmental disabilities. Further

selection criteria were that the child score between

30 and 75 on the Bayley Scales of Infant Devel-

Method

opment II (see Measures). Borderline group chil-

Participants dren had Bayley II scores of 76 to 84. Delayed

Participants were 214 families, recruited to and borderline children were combined in the

participate in a longitudinal study of young chil- present analyses and designated as ‘‘delayed.’’

dren from ages 3 to 5 years, with samples drawn Nondelayed group families were recruited primar-

from Southern California and Central Pennsyl- ily through local preschools and daycare programs

vania. This Collaborative Family Study is based that serve the same catchment areas as the agen-

at three universities: Penn State University, Uni- cies that support delayed group children. Further

versity of California, Los Angeles, and University selection criteria were that the child (a) score 85

of California, Riverside. All procedures were ap- or above on the Bayley II and (b) not have been

proved by the Institutional Review Boards of the born prematurely or have had any developmental

three universities involved. The present sample disability.

was comprised of all families for whom data were Table 2 shows demographics separately for

available on the primary measures across child the children with developmental delays and those

ages 3, 4, and 5; this constitutes 92% of the orig- with no delays and their parents. Child age at in-

inally recruited sample. take averaged 35.2 months (SD ⫽ 2.9) and the

School and agency personnel mailed bro- majority were boys (59%). Most children in the

chures describing the study to families who met delayed group had not received a specific diag-

selection criteria, and interested parents phoned nosis; when there was one, the most frequent was

Table 2. Study 2: Child and Family Demographics by Delay Status

Delayed No delay

(n ⫽ 92) (n ⫽ 122)

Variable Mean/% Mean/% t/⌾2a

Child

Mean age at testingb (SD) 35.6 (2.9) 34.9 (3.2) 1.73

Gender (% boys) 66.3 53.3 3.16

Mean BSID II: MDIc 60.3 (13.0) 104.2 (11.6) 25.97***

Parent and family

Marital status (% married) 80.4 88.5 2.10

Mean mother age (years) 32.5 (6.2) 34.1 (5.6) 1.93

Mean mother education (grade) 14.3 (2.4) 15.8 (2.5) 4.30***

Mother employment (%) 48.9 60.7 2.47

Mother race (% Caucasian) 58.7 66.4 1.02

Mean father education (grade)d 14.0 (2.7) 15.7 (2.9) 4.22***

Family income (%$50K⫹) 41.3 57.9 5.08*

a

ts are used when standard deviations are reported. bIn months. cBayley Scales of Infant Development, Mental Devel-

opment Index. dNs ⫽ 80 for the delayed group and 116 for the nondelayed group, respectively.

*p ⬍ .05. ***p ⬍ .001.

338 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

Down syndrome or cerebral palsy. Most mothers of 15. Bayley (1993) reported high short-term

(85%) were married because recruitment had ini- test–retest reliability for the MDI, r ⫽ .91.

tially focused on intact families. Mother’s race/ Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale IV (Thorndike,

ethnicity was predominantly Caucasian (63%) or Hagan, & Sattler, 1986). Classification of children

Latina (21%). Mothers and fathers averaged about as delayed or not delayed at 60 months was based

15 years of school, and 51% of families had an on the 60-month administration of the Stanford

annual income of $50,000 or more. Binet, administered in an assessment session at

The two status groups did not differ on the the clinic.

child attributes shown in Table 2. except on Bay- Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1½–5 CBCL

ley II scores. On parent and family attributes, the (Achenbach, 2000). This new version of the widely

highest grade completed in school was higher for used CBCL is aimed at the preschool years. It has

mothers and fathers in the nondelayed group as 99 items that indicate child problems, listed in

was family income. However, because parent ed- alphabetical order (from ‘‘aches and pains without

ucation and family income were unrelated to the medical cause’’ to ‘‘worries’’) and one ‘‘other’’

variable of interest namely, positive impact item. The respondent indicates, for each item,

these were not covaried in analyses. whether it is not true (0), somewhat or sometimes true

(1), or very true or often true (2), now or within the

past 2 months. We utilized only total problem

Assessment Procedure

scores; these are converted to T scores with a

The data examined in this study were ob-

mean of 50 and an SD of 10. Total score alphas

tained in two ways. The initial measures of child

for the present sample at the initial assessment

developmental level and problem behaviors were

were .94 for both mothers and fathers. For some

obtained at a home intake assessment session con-

analyses, behavior problem groups were deter-

ducted when the child was between 30 and 40

mined from parents’ CBCL Total T scores follow-

months of age. Prior to this session, parents had

ing Achenbach’s (1991) suggested cut-offs. These

completed a telephone intake interview with staff

were designated as low (T score ⬍ 60, indicating

and had received an informed consent form. Two

nonclinical range) and high (T score ⱖ 60, indi-

trained research assistants visited the family to re-

cating borderline or clinical range).

view procedures, obtain informed consent, and

administer the Bayley II to the child. Mother, and

father if present, completed a demographic ques- Results

tionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist

(CBCL, see discussion below). The CBCL was ob- Positive Impact Inferred From Low Negative

tained again at home assessment sessions when We examined the view that positive impact

the child was 48 and 60 months of age. The FIQ can be inferred from low scores on measures of

(see Study 1) was part of a packet completed dur- well-being. At child age 36 months, positive im-

ing each annual assessment. This packet also in- pact correlated inversely with negative impact, r

cluded the CES-D (see Study 1); alpha for the ⫽ ⫺.38, p ⬍ .001. Positive impact and negative

present sample was .89. Families were paid an impact were each divided into thirds and com-

honorarium for participation. pared in cross-tabs. Of the 75 cases in the lowest

third on negative impact, 48% fell into the highest

third on positive impact. Here, too, although

Measures

there was a modest correlation between positive

Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (Bayley,

and negative impact, if only the low third of neg-

1993). Classification of children as delayed or not

ative impact were used for determining positive

delayed at 36 and 48 months was based on the

impact, about half of the sample would have been

36-month Bayley II. This is a widely used assess-

misclassified. Positive impact was not significantly

ment of mental and motor development in chil-

correlated with depression, r ⫽ ⫺.08.

dren aged 1 to 42 months. It was administered in

the child’s home, with the mother present. In

most cases, there was a primary examiner and an Positive Impact by Child Delay Status and

assistant. Only mental development items were Behavior Problems

administered; the Mental Development Index Child behavior problems were designated as

(MDI) is normed with a mean of 100 and an SD low (nonclinical range, see Method) or high (bor-

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 339

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

Table 3. Positive Impact Reported by Mothers and Fathers of Young Children at Ages 3, 4, and 5

Years by Delay Status (DS) and Behavior Problems (BP)

Delayed No delay

Parent/

Child agea Low BP Hi BP Low BP Hi BP F (DS) F (BP) F (DS ⫻ BP)

Mothers

3 15.7 14.3 16.4 15.0 0.72 2.62 0.00

4 16.3 13.1 16.3 12.9 0.02 14.52*** 0.01

5 15.2 14.7 16.5 12.7 0.15 5.48* 3.22

Fathers

3 17.7 15.2 17.2 14.2 0.80 11.27*** 0.14

4 16.4 14.5 17.1 15.6 1.03 3.72⫹ 0.05

5 16.7 14.2 16.8 14.0 0.00 6.69** 0.02

Child age in years.

a

⫹p ⬍.10. *p ⬍ .05. **p ⬍ .01. ***p ⬍ .001.

derline/clinical range) at each assessment. Sepa- Neither the time (child age) main effect nor the

rate 2 (behavior problem level) ⫻ 2 (delay status) Parent Gender ⫻ Time interaction was significant.

ANOVAS were conducted on positive impact, for

mothers and fathers, at each assessment (child age Positive Impact by Culture

3, 4, and 5 years). Table 3 shows mean scores and We have seen in the whole sample that par-

F values for delay status, behavior problems, and ents of children with developmental delays and

the interaction. Delay status had no relationship those with children without delays reported nearly

to positive impact in any analysis, a finding that identical positive impact. This finding, however,

is considered further in our examination of cul- could mask a difference between cultural groups.

ture. Clinical-level child behavior problems, how- Table 4 shows means for Anglo and Latino par-

ever, were associated with lower positive impact

in every comparison; for mothers and fathers, the

Table 4. Positive Impact at Child Ages 3, 4, and

relationship was statistically significant in four of

5 Years by Parent and Culture

the six ANOVAs. The Delay Status ⫻ Behavior

Problems interaction term was not significant in Parent Age 3 Age 4 Age 5

any analysis.

Mother 15.6 15.7 15.4

Father 16.8 16.4 16.3

Positive Impact by Parent Gender t (paired) 2.96 1.49 2.00

There was a moderate relationship between df 189 181 177

mother and father positive impact scores at each P .003 ns .047

of the three assessments, rs ⫽ .31, .32, and .43,

respectively, all ps ⬍ .001. Correlations of positive Culture

impact scores across assessments were moderately Anglo mother 15.1 15.3 15.0

high for mothers and for fathers, ranging from .60 Latina mother 17.4 16.4 16.5

to .75, all ps ⬍ .001. Positive impact in the com- t (independent) 2.90 1.23 1.66

bined sample by parent gender (mother, father) is df 178 175 178

shown in Table 4; at each time-point, fathers ex- P .004 ns .098

pressed greater positive impact than did mothers. Anglo father 16.4 15.9 15.6

A repeated measures ANOVA on positive impact Latino father 17.7 18.0 18.3

by parent gender (mother, father) and child age

t (independent) 1.24 2.75 3.20

(3, 4, and 5), showed a significant main effect for

df 154 149 148

parent gender (Ms for mothers and fathers ⫽

P ns .008 .002

15.39 and 16.31, respectively, F ⫽ 5.90, p ⫽ .016.

340 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

ents across the three time points, with consistently or interaction effects of time approached signifi-

higher scores for Latino parents. The relationship cance in mother or father analyses.

between delay status and positive impact was an-

alyzed further within these two cultural subgroups

that corresponded to those in Study 1. Because Positive Impact as Moderator of Child

mothers and fathers in some families had different Behavior Problems and Parenting Stress

ethnicities, we ran analyses separately for each par- We have found a strong relationship be-

ent. Two repeated measures ANOVAs were run tween child behavior problems and both moth-

on Positive Impact ⫻ Delay Status (delays, no de- ers’ and fathers’ perceived negative impact, or

lays) and ethnicity (Anglo, Latino) across child parenting stress, at every assessment point. We

ages 3, 4, and 5. Latina mothers (n ⫽ 44) reported further examined whether positive impact had a

higher positive impact than did Anglo mothers (n moderator effect on this relationship, through re-

⫽ 135), but the difference did not reach statistical gression analyses on the FIQ Negative Impact

significance. There was, however, a significant in- score at each assessment. For each analysis, we

teraction between culture and delay group, first identified demographic variables that corre-

F(1, 173) ⫽ 4.23, p ⫽ .04. Figure 3 shows the lated with negative impact and entered these con-

marginal means. In the no delay group, expression trol variables as Step 1. Step 2 was behavior prob-

of positive impact was about the same for Anglo lems (CBCL Total score) and Step 3 was FIQ

and Latina mothers. In the developmental delay Positive Impact. For Step 4, following the same

group, Anglo mothers expressed lower positive procedures as in Study I, we converted the CBCL

impact than did Anglo mothers in the no delay and Positive Impact scores to z scores and en-

group, whereas Latina mothers expressed higher tered the product of these two z scores as a test

positive impact than did Latina mothers in the no for moderation. For mothers at child age 3, these

delay group. variables accounted for 56.1% of the variance in

Figure 3 also shows results for fathers, which negative impact. The control variables (child IQ,

were highly similar to those for mothers. Latino child gender, and mother education) accounted

fathers reported marginally more positive impact for 10.1%, F(3, 209) ⫽ 7.85, p ⬍ .001, behavior

than did Anglo fathers, F(1, 138) ⫽ 3.69, p ⫽ problems accounted for an additional 37.4%,

.057. There was a similar interaction between cul- F(change, 1, 208) ⫽ 147.95, p ⬍ .001, and pos-

ture and delay group, although only marginally itive impact accounted for an additional 6.7%,

significant, F(1, 138) ⫽ 3.68, p ⫽ .057. No main F(change, 1, 207) ⫽ 30.40, p ⬍ .001. The inter-

Figure 3. Study 2. Delay status and positive impact in Anglo and Latino families.

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 341

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

action term, indicating moderation, accounted pact accounted for significant variance in negative

for an additional 1.9%, F(change; 1, 206) ⫽ 8.77, impact beyond child behavior problems at child

p ⫽ .003. In the final model, behavior problems, ages 3, 4, and 5 years, all ps ⬍ .001. Positive im-

p ⬍ .001, positive impact, p ⬍ .001, the inter- pact was also a significant moderator at ages 4 and

action term, p ⬍ .01, and child IQ, p ⬍ .05, were 5; the interaction term was significant at p ⬍ .001.

all significant. At 36 months, however, the interaction was not

At child ages 4 and 5 years, results for mother significant.

negative impact were highly similar, with 58.4%

and 65.3% of the variance in negative impact ac-

counted for. The control variables (in these anal-

Discussion

yses, child IQ and maternal health) accounted for We examined the positive impact of a child

12.9% and 15.7%, respectively, both ps ⬍ .001. with an intellectual disability on mothers and fa-

Behavior problems accounted for an additional thers in two samples of families: those with (a)

38.2% and 37.9%, both F(changes), p ⬍ .001. Pos- preschool children (with borderline, mild, or

itive impact accounted for an additional 4.2% and moderate intellectual disabilities or without intel-

7.3%, both F(changes), p ⬍ .001. The interaction lectual disabilities) and (b) young adults with se-

term, indicating moderation, accounted for an ad- vere intellectual disabilities. We proposed three

ditional 3.0% at age 4, F change (1, 199) ⫽ 14.37, ways one could conceptualize positive impact: as

p ⬍ .001, and 4.4% at age 5, F change (1, 208) ⫽ low negative outcomes, as common benefits (the

26.49 p ⬍ .001. All of the interactions reported same child-rearing benefits enjoyed by parents of

evidenced the same pattern of effect as that shown children without disabilities), and as special ben-

in Figure 4, which illustrates the moderation effect efits (derived because of the disability).

at age 5 graphically, with the main and moderator Our first question was, Can positive impact

variables centered (Aiken & West, 1991). be inferred from low scores on measures of neg-

We repeated these three regression analyses ative impact or well-being? Findings from these

for fathers, with very similar results. Positive im- two very different samples indicated that inferring

Figure 4. Study 2. Positive impact moderates the relationship between child behavior problems and

parenting stress (mothers, at child age 3 years). Square, high; triangle, moderate; and circle, low positive

impact.

342 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

positive impact from low negative impact would we focused on parent gender and cultural back-

be wrong as often as it would be correct, thus ground. Within the preschool-age sample, reports

providing little support for the low negative per- by mother and fathers of their perceptions of pos-

spective. Moreover, positive impact was unrelated itive impact of parenting were not appreciably dif-

to another measure of well-being, depression, in ferent, although fathers reported significantly

both samples. Although low scores on measures higher scores. As noted earlier, Hastings, Kor-

of psychopathology are, of course, desirable, one shoff‘ et al. (2005), using a different assessment of

must be cautious in interpreting these as related positive perceptions, found that mothers reported

to disability. Even when parents of children with slightly higher scores. To date, perceptions of pos-

and those without disability differ on these mea- itive impact cannot be said to systematically differ

sures, the difference is primarily related to child by parent gender.

behavior problems, not the disability per se (Baker Regarding culture, we sought to replicate and

et al., 2002). Also, as we have seen here, low neg- extend our previous finding in the sample of

ative scores do not strongly predict high scores on young adults with severe disability: that Latina

a more direct measure of positive impact. mothers reported much higher positive impact

Our second question was, Would there be than did Anglo mothers. We contrasted Latino

group differences on a measure designed to assess and Anglo subsamples from the young child sam-

common benefits? To address this question, we ple and replicated this finding with both mothers

utilized a Positive Impacts scale that is equally ap- and fathers. Within the whole young child sam-

propriate for parents of children with and without ple, we had found no relationship between delay

disability. In Study 2, parents of preschool-aged status and positive impact. However, an impor-

children with developmental delays or no delays tant difference was masked by combining Latino

differed significantly on a measure of negative im- and Anglo parents because there was a significant

pact, or stress. We had previously found that in relationship between culture and delay group.

this sample positive impact at child age 3 years With typically developing children, Anglo and La-

did not differ between families of delayed and typ- tino mothers and fathers reported about the same

ically developing children (Baker et al., 2002), and extent of positive impact. However, with devel-

in the present analyses we found no delay status opmentally delayed children, Anglo mothers and

differences at ages 4 and 5 years as well. The ex- fathers both reported lower positive impact (as ex-

pression of common benefits of parenting across pected), but Latino mothers and fathers both re-

families with and without disability, despite dif- ported higher positive impact. Although this De-

ferences in negative impact, lends support to the lay Status ⫻ Culture interaction was of only bor-

two-factor model of caregiving appraisal (Pruchno derline statistical significance, these results were

et al., 1996) and tempers the exclusively negative consistent with the very large cultural group dif-

perspective that has characterized earlier literature ference in the sample of young adults, all of

on families and disability. whom had developmental disabilities.

Our third question of interest was, Do par- To understand Latino families’ increase in

ents’ reports of positive impact vary by child be- positive views in the face of disability, consider

havioral challenges? In the present studies, par- this expression ‘‘No hay mal que por bien no ven-

ents’ reports of positive impact were significantly ga,’’ which translates ‘‘there is nothing bad out of

inversely related to young adult behavior/mental which good cannot come’’ (Zuniga, 1992, p. 151).

health problems and to child behavior problems This positive expression reflects cultural beliefs re-

at all three assessments. This is consistent with lated to disability, family, and religion. For ex-

other findings, noted above, that child behavioral ample, Latina and non-Latina mothers may hold

challenges accounted for more variance in nega- some different beliefs about what are considered

tive indicators of parental well-being than did dis- acceptable child-rearing practices. Juarez (1985)

ability status in the present samples (Baker et al., noted that, in some Latino families, it might be

2002, 2003; McIntyre et al., 2002) and others deemed acceptable for a nondelayed preschooler

(Floyd & Gallagher, 1997; Poehlmann, Clements, to drink from a baby bottle or a preteen to still

Abbeduto, & Farsad, 2005). sit in her or his mother’s lap. Thus, when the son

Our fourth question was, Which factors be- or daughter has a disability, especially a grown

yond the child might contribute to positive per- ‘‘child’’ of age 20 or more whose caregiving needs

ceptions of parenting? To address this question, resemble those of a young child, the daily care

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 343

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

burden may be perceived as less stressful or drain- theless, there is potential usefulness for including

ing for Latino families than for Anglo ones. In- this aspect in parent education or intervention

deed, a lack of push for independence of growing programs, particularly where there is an emphasis

children is characteristic of some cultures, even on cognitions about parenting.

more so when there is a child or young adult with Our final question was, Do parents’ percep-

a severe disability (Rueda, Monzo, Shapiro, Go- tion of positive contributions of the child with

mez, & Blacher, 2005). Religious belief systems disability buffer the established relationship be-

also may incline Latina mothers toward positive tween child behavior problems and parenting

reframing, providing families with a spiritual stress? In both samples, positive impact had a

framework for understanding the disability and main effect relationship to parenting stress; moth-

for providing hope (Zuniga, 1998). ers and fathers who perceived greater positive im-

Latina mothers may report more positive im- pact reported lower parenting stress. Moreover,

pact of their child with disabilities on parenting, there were significant Positive Impact ⫻ Behav-

in part because of the importance of the parent– ioral Challenge interactions in the young adult

child relationship in Latino families and the sample and in the preschool sample for mothers

mother’s own views of her child’s characteristics. at all three time points and for fathers at two of

One interpretation of mother’s positive percep- three time points. Thus, when child-rearing chal-

tions reflects attribution theory. In an earlier study lenges were lower, there was little relationship be-

of 149 Latina mothers of children with develop- tween positive views of parenting and experienced

mental disabilities, Chavira, Lopez, Blacher, and stress. However, when child-rearing challenges

Shapiro (2000) found that most mothers view were higher, parents who held the least positive

their child as not responsible for his or her be- views of parenting reported the greatest stress. Al-

havior problems. By not attributing cause to the though studies have repeatedly linked child be-

child, mothers avoid the formulation of negative havioral challenges to lowered parental well-being,

emotions. Another interpretation reflects the em- there is always considerable unexplained variance

beddedness of the child in the family, and Latina in the well-being variables. The present finding,

mothers’ great pride and responsibility in their that perceptions of positive impact moderate the

knowledge of their child. Thus, as reported in relationship between child challenge and parental

Rueda et al. (2005), Latinas often feel that they stress, is particularly important because it was

are better able to make child-related decisions manifested in two large samples quite different in

than are professionals. This empowerment is like- age and level of disability. This finding relates to

ly very satisfying and positive. Furthermore, Lati- a larger body of literature on positive thinking.

na mothers often perceive their child as more Several researchers have found that positivism in

competent than do professionals who assess or the form of perceptions of positive meaning lead

provide services to the child. In speaking about to better outcomes in health domains, such as

her young adult son who functioned at the level breast cancer (Bower, 2005; Bower & Segerstrom,

of a 6-year-old, one mother said: ‘‘He is a very 2004). Examining mechanisms, Taylor, Lerner,

handsome young man and he is attending the Sherman, Sage, and McDowell (2003) found that

Easter Seals and his functional level is basically a forms of positive illusions or beliefs actually re-

moderate mental retardation, very intelligent’’ duced cardiovascular responses to stress and pro-

(Rueda et al., 2005, p. 7). duced lower baseline levels of cortisol.

Given the empirical evidence of successful in- Models of stress and coping pertaining di-

terventions for depression that have been formu- rectly to families and disability posit that the re-

lated from a positive psychology perspective (Se- lationship between child stressors and parental

ligman et al., 2005), the possibility of building on well-being is affected by resources (e.g., income,

Latina mothers’ positive perceptions in interven- social support) and cognitions (e.g., McCubbin &

tion programs for parents who have children with Patterson, 1983). Although some investigators

disabilities is compelling. We note the impor- have examined the moderating role of resources

tance, though, of documenting and considering (e.g., Suarez & Baker, 1997), there is a need to

culturally relevant variables because Latina moth- study further the personality characteristics that

ers have reported some alienation in their expe- parents bring with them to parenting, as well as

riences with service delivery systems (Shapiro, attitudes concerning parenting, as possible buffers

Monzo, Rueda, Gomez, & Blacher, 2004). None- of child-rearing challenges. Recently, reported re-

344 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

search with the Study 2 sample found that the Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., Kopp, C. B., & Kraemer,

personality trait of dispositional optimism mod- B. (1997). Parenting children with mental re-

erated this relationship for mothers (Baker et al., tardation. International Review of Research in

2005). The present findings also support the mod- Mental Retardation, 20, 1–45.

el of cognitions as moderators of child challenges Baker, B. L., Heller, T. L., & Henker, B. (2000).

on parental outcome. However, it is notable that Expressed emotion, parenting stress, and ad-

in the Study 1 sample, positive views of parenting justment in mothers of young children with

and dispositional optimism were not significantly behavior problems. Journal of Child Psychology

related. and Psychiatry, 41, 907–915.

Finally, we note that longitudinal perspectives Baker, B. L., McIntyre, L. L., Blacher, J., Crnic,

on positive impact of disability are lacking in the K., Edelbrock, C., & Low, C. (2003). Pre-

literature. In the present study, positive impact school children with and without develop-

was stable across the preschool years. Poehlmann mental delay: Behavior problems and parent-

et al. (2005) have suggested that by the time a ing stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Dis-

child with intellectual disability reaches adoles- ability Research, 47, 217–230.

cence, parents have had more time to reflect on Bayley, N. (1993). Bayley Scales of Infant Develop-

the son’s or daughter’s positive attributes and to ment Second Edition: Manual. San Antonio:

develop more positive perceptions. We note that Psychological Corp.

within the disability groups of our studies report- Behr, S. K., Murphy, D. L., & Summers, J. A.

ed here, Anglo mothers’ positive impact mean (1992). User’s manual: Kansas Inventory of Pa-

score was 14.5 in the 3-year old sample and 12.0 rental Perceptions (KIPP). Lawrence: University

in the young adult sample, whereas Latina moth- of Kansas, Beach Center on Families and Dis-

ers had almost identical scores (Ms ⫽ 17.7 and ability.

17.6 in the two samples, respectively). These sam- Billingsley, A. (1992). Black families in white Amer-

ples, of course, differed in many respects, so al- ica. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

though these means do not support Poehlmann Blacher, J., & Baker, B. L. (2002). The best of

et al.’s hypothesis of more positive perceptions AAMR. Families and mental retardation: A col-

over time, the question can only adequately be lection of notable AAMR journal articles across

addressed longitudinally and in different cultural the 20th century. Washington, DC: American

contexts. Association on Mental Retardation.

Blacher, J., & McIntyre, L. L. (2006). Syndrome

specificity and behavioural disorders in young

References adults with intellectual disability: Cultural dif-

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Child ferences in family impact. Journal of Intellectual

Behavior Checklist 4–18. Burlington: Universi- Disability Research, 50, 184–198.

ty of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. Blacher, J., Shapiro, J., Lopez, S., Diaz, L., & Fus-

Achenbach, T. M. (2000). Manual for the Child co, J. (1997). Depression in Latina mothers of

Behavior Checklist 1½–5. Burlington: Univer- children with mental retardation: A neglected

sity of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. concern. American Journal on Mental Retarda-

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regres- tion, 101, 83–96.

sion: Testing and interpreting interactions. New- Bower, J., Meyerowitz, B. E., Desmond, K. A.,

bury Park, CA: Sage. Bernaards, C. A., Rowland, J., & Patricia, A.

Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., & Olsson, M. (2005). Pre- (2005). Perceptions of positive meaning and

school children with and without develop- vulnerability following breast cancer predic-

mental delay: Behaviour problems, parents’ tors and outcomes among long-term breast

optimism, and well being. Journal of Intellectual cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medi-

Disability Research, 49, 575–590. cine, 29, 236–245.

Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., Crnic, K. A., & Edel- Bower, J. E., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2004). Stress

brock, C. (2002). Behavior problems and par- management, finding benefit, and immune

enting stress in families of three-year-old chil- function: Positive mechanisms for interven-

dren with and without developmental delays. tion effects on physiology. Journal of Psycho-

American Journal on Mental Retardation, 107, somatic Research, 56, 9–11.

433–444. Bruininks, R. H., Woodcock, R. W., Weather-

䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 345

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

man, R. F., & Hill, B. K. (1996). Scales of In- mental retardation services. American Journal

dependent Behavior Revised comprehensive man- on Mental Retardation, 109, 53–62.

ual. Itasca, IL: Riverside. Hastings, R. P., Korshoff, H., Brown, T., Ward,

Chavira, V., Lopez, S. R., Blacher, J., & Shapiro, N. J., Espinosa, F. D., & Remington, B.

S. (2000). Latina mothers’ attributions, emo- (2005). Coping strategies in mothers and fa-

tions, and reactions to the problem behaviors thers of preschool and school-age children

of their children with developmental disabil- with autism. Autism, 9, 377–391.

ities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Hastings, R. P., & Taunt, H. M. (2002). Positive

41, 245–252. perceptions in families of children with de-

Cox, A. H., Marshall, E. S., Mandleco, B., & Ol- velopmental disabilities. American Journal on

sen, S. F. (2003). Coping responses to daily Mental Retardation, 107, 116–127.

life stressor of children who have a disability. Hauser-Cram, P., Warfield, M. E., Shonkoff, J. P.,

Journal of Family Nursing, 9, 397–413. & Krauss, M. W. (2001). Children with dis-

Dyson, L. L. (1997). Fathers and mothers of abilities: A longitudinal study of child devel-

school-age children with developmental dis- opment and parent well-being. Monographs of

abilities: Parental stress, family functioning, the Society for Research in Child Development, 66,

and social support. American Journal on Men- 1–131.

tal Retardation, 102, 267–279. Helff, C. M., & Glidden, L. M. (1998). More pos-

Floyd, F. J., & Gallagher, E. M. (1997). Parental itive or less negative? Trends in research on

stress, care demands, and use of support ser- adjustment of families rearing children with

vices for school-age children with disabilities developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation,

and behavior problems. Family Relations, 46, 36, 457–464.

359–371. Hodapp, R. M., Glidden, L. M., & Kaiser, A. P.

Floyd, F. J., & Phillippe, K. A. (1993). Parental (2005). Siblings of persons with disabilities:

interactions with children with and without Toward a research agenda. Mental Retardation,

mental retardation: Behavior management, 43, 334–338.

coerciveness, and positive exchange. American Holroyd, J. (1985). Questionnaire on Resources and

Stress manual. Unpublished manuscript, Uni-

Journal on Mental Retardation, 97, 673–684.

versity of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsy-

Folkman, S. (1997). Positive psychological states

chiatric Institute.

and coping with severe stress. Social Science

Juarez, R. (1985). Core issues in psychotherapy

and Medicine, 45, 1207–1221.

with the Hispanic child. Psychotherapy, 22,

Friedrich, W. N., Greenberg, M. T., & Crnic, K.

441–448.

(1983). A short-form of the Questionnaire on

Lawton, M. R., Moss, M., Kleban, M. H., Glicks-

Resources and Stress. American Journal of Men-

man, A., & Ravine, M. (1991). A two-factor

tal Deficiency, 88, 41–48. model of caregiving appraisal and psycholog-

Gallimore, R., Hoots, J. J., Weisner, T. S., Garnier, ical well-being. Journal of Gerontology: Psycho-

H. E., & Guthrie, D. (1996). Family responses logical Sciences, 46, 181–189.

to children with early developmental disabil- Lynch, E. W., & Hanson, M. J. (2004). Developing

ities II: Accommodation intensity and activity cross-cultural competence (3rd ed.). Baltimore:

in early and middle childhood. American Jour- Brookes.

nal on Mental Retardation, 101, 215–232. Margalit, M., & Ankonina, D. B. (1991). Positive

Hastings, R. P., Allen, R., McDermott, K., & Still, and negative affect in parenting disabled chil-

D. (2002). Factors related to positive percep- dren. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 4, 289–

tions in mothers of children with intellectual 299.

disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intel- McCubbin, H. I., & Patterson, J. (1983). Family

lectual Disabilities, 15, 269–275. transition: Adaptation to stress. In H. I.

Hastings, R. P., Beck, A., & Hill, C. (2005). Posi- McCubbin & C. R. Figley (Eds.), Stress and the

tive contributions made by children with an family: Vol. I. Coping with normative transitions

intellectual disability in the family. Journal of (pp. 5–23). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Intellectual Disabilities, 9, 155–165. McIntyre, L. L., Blacher, J., & Baker, B. L. (2002).

Hastings, R. P., & Horne, S. (2004). Positive per- Behaviour/mental health problems in young

ceptions held by support staff in community adults with intellectual disability: The impact

346 䉷 American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 112, NUMBER 5: 330–348 円 SEPTEMBER 2007 AMERICAN JOURNAL ON MENTAL RETARDATION

Positive impact of intellectual disability J. Blacher and B. L. Baker

on families. Journal of Intellectual Disability Re- pact of children with an intellectual disability

search, 46, 239–249. on the family. Journal of Intellectual and Devel-

Phares, V. (1996). Fathers and developmental psycho- opmental Disability, 23, 57–70.

pathology. New York: Wiley. Suarez, L. M., & Baker, B. L. (1997). Child exter-

Poehlmann, J., Clements, M., Abbeduto, L., & nalizing behavior and parents’ stress: The role

Farsad, V. (2005). Family experiences associ- of social support. Family Relations, 47, 373–

ated with a child’s diagnosis of fragile X or 381.

Down syndrome: Evidence for disruption and Summers, J. A., Behr, S. K., & Turnbull, A. P.

resilience. Mental Retardation, 43, 255–267. (1989). Positive adaptation and coping

Pruchno, R. A., Patrick, J. M. H., & Burant, C. strengths of families who have children with

(1996). Mental health of aging women with disabilities. In G. H. S. Singer & L. K. Irvin

children who are chronically disabled: Ex- (Eds.), Support for caregiving families: Enabling

amination of a two-factor model. Journal of positive adaptation to disabilities (pp. 27–40).

Gerontology: Social Sciences, 51B, S284–296. Baltimore: Brookes.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self- Taunt, H. M., & Hastings, R. P. (2002). Positive

report depression scale for research in the gen- impact of children with developmental disabil-

eral population. Applied Psychological Measure- ities on their families: A preliminary study. Ed-

ment, 1, 385–401. ucation and Training in Mental Retardation and

Reiss, S. (1994). Reiss Screen for Maladaptive Be- Developmental Disabilities, 37, 410–420.

havior: Test manual (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Taylor, S. E. (1983). Adjustment to threatening

IDS. events: A theory of cognitive adaptation.

Rogers-Dulan, J., & Blacher, J. (1995). African American Psychologist, 38, 1161–1173.

American families, religion, and disability: A Taylor, S. E., Kemeny, M. E., Reed, G. M., Bower,

conceptual framework. Mental Retardation, 33, J. E., & Gruenewald, T. L. (2000). Psycholog-

226–238. ical resources, positive illusions, and health.

Rueda, R., Monzo, L., Shapiro, J., Gomez, J., & American Psychologist, 55, 99–109.

Blacher, J. (2005). Cultural models of transi- Taylor, S. E., Lerner, J. S., Sherman, D. K., Sage,

tion: Latina mothers of young adults with de- R. M., & McDowell, N. K. (2003). Are self-

velopmental disabilities. Exceptional Children, enhancing cognitions associated with healthy

71, 1–14. or unhealthy biological profiles? Journal of Per-

Sandler, A. G., & Mistretta, L. A. (1998). Positive sonality and Social Psychology, 85, 605–615.

adaptation in parents of adults with disabili- Thorndike, R. L., Hagen, E. P., & Sattler, J. M.

ties. Education and Training in Mental Retar- (1986). The Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale,

dation and Developmental Disabilities, 33, 123– Fourth edition: Technical manual. Chicago: Riv-

130. erside.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Pe- Turnbull, A. P., Patterson, J. M., Behr, S. K., Mur-

terson, C. (2005). Positive psychology pro- phy, D. L., Marquis, J. G., & Blue-Banning,