Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pane Presitoria

Uploaded by

umberto de vonderweidOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pane Presitoria

Uploaded by

umberto de vonderweidCopyright:

Available Formats

Feature

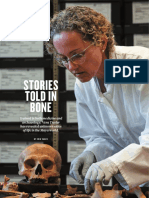

VINCENT J. MUSI

THE ANCIENT CARB

Grains were on the menu more than 11,000 years ago at Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, even before crops were domesticated.

REVOLUTION

Well before people domesticated crops, they were grinding

grains for beer and hearty dishes. By Andrew Curry

O

n a clear day, the view from the ruins that its T-shaped pillars and circular enclo- Tepe, suggesting that its residents hadn’t yet

of Göbekli Tepe stretches across sures pre-date pottery in the Middle East. made the leap to farming. The ample animal

southern Turkey all the way to the The people who built these monumental bones found in the ruins prove that the people

Syrian border some 50 kilometres structures were living just before a major living there were accomplished hunters, and

away. At 11,600 years old, this transition in human history: the Neolithic there are signs of massive feasts. Archaeol-

mountaintop archaeological site revolution, when humans began farming and ogists have suggested that mobile bands of

has been described as the world’s domesticating crops and animals. But there hunter-gatherers from all across the region

oldest temple — so ancient, in fact, are no signs of domesticated grain at Göbekli came together at times for huge barbecues,

488 | Nature | Vol 594 | 24 June 2021

©

2

0

2

1

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

and that these meaty feasts led them to build to produce porridge and beer. Archaeologists perception was to go back to the kitchen. That

the impressive stone structures. had long argued that stone vats at the site was the inspiration of Soultana Valamoti, an

Now that view is changing, thanks to were evidence of occasional ceremonial beer archaeobotanist at the Aristotle University of

researchers such as Laura Dietrich at the Ger- consumption at Göbekli Tepe, but thought of Thessaloniki in Greece who, not coinciden-

man Archaeological Institute in Berlin. Over it as a rare treat. tally, is also a passionate home cook. Valam-

the past four years, Dietrich has discovered Teasing answers from the stones there oti spent the early years of her career toting

that the people who built these ancient struc- and at other sites is not a simple process. In buckets and sieves from one excavation site

tures were fuelled by vat-fulls of porridge and archaeology, it is much easier to spot evidence to another across Greece, all while combing

stew, made from grain that the ancient resi- of meat meals than ones based on grains or museum storerooms for ancient plant remains

dents had ground and processed on an almost other plants. That’s because the bones of to analyse. The work convinced her there was

industrial scale1. The clues from Göbekli Tepe butchered animals fossilize much more readily an untapped wealth of evidence in burnt food

reveal that ancient humans relied on grains than do the remains of a vegetarian feast. The remains — if she could find a way to identify

much earlier than was previously thought — fragile nature of ancient plant remains makes what she was looking at.

even before there is evidence that these plants archaeobotany — the study of how ancient peo-

were domesticated. And Dietrich’s work is part ple used plants — tricky, time-consuming work.

of a growing movement to take a closer look Researchers use sieves, fine mesh and buckets

at the role that grains and other starches had to wash and separate debris from archaeolog- That’s revolutionary.

in the diet of people in the past. ical sites. Tiny bits of organic material such

The researchers are using a wide range of as seeds, charred wood and burnt food float

It’s an unprecedented

techniques — from examining microscopic to the top, while heavier dirt and rocks sink. source of information.”

marks on ancient tools to analysing DNA resi- The vast majority of what emerges amounts

dues inside pots. Some investigators are even to the raw ingredients, the bits that never made

experimentally recreating 12,000-year-old it into a pot. By identifying and counting grass More than 20 years ago, Valamoti decided

meals using methods from that time. Look- seeds, grain kernels and grape pips mixed into to turn her lab into an experimental kitchen.

ing even further back, evidence suggests that the soil, archaeobotanists can tell what was She ground and boiled wheat to make bulgur,

some people ate starchy plants more than growing in the area around the settlement. and then charred it in an oven to simulate a

100,000 years ago. Taken together, these Unusual amounts of any given species offer cir- long-ago cooking accident (see ‘Fast food of

discoveries shred the long-standing idea that cumstantial evidence that those plants might the Bronze Age’). By comparing the burnt

early people subsisted mainly on meat — a view have been used, and perhaps cultivated, by remains to 4,000-year-old samples from a site

that has fuelled support for the palaeo diet, people in the past. in northern Greece, she was able to show that

popular in the United States and elsewhere, Some of the earliest evidence for plant the ancient and modern versions matched, and

which recommends avoiding grains and other domestication, for example, comes from that this way of preparing grain had its roots

starches. einkorn wheat grains recovered from a site in the Bronze Age3.

The new work fills a big hole in the under- near Göbekli Tepe that are subtly different Over the decade that followed, she con-

standing of the types of food that made up in shape and genetics from wild varieties2. At tinued experimenting. Beginning in 2016, a

ancient diets. “We’re reaching a critical mass Göbekli Tepe itself, the grains look wild, sug- European Research Council grant allowed her

of material to realize there’s a new category gesting that domestication hadn’t taken place to create a crusty, charred reference collec-

we’ve been missing,” says Dorian Fuller, an or was in its earliest stages. (Archaeologists tion of more than 300 types of ancient and

archaeobotanist at University College London. suspect that it might have taken centuries for experimental samples. After making bread

domestication to alter the shape of grains.) dough, baked bread, porridge, bulgur and a

A garden of grinding stones Direct proof that plants landed in cooking traditional food called trachana from heirloom

Dietrich’s discoveries about the feasts at pots is harder to come by. To work out what wheat and barley, Valamoti chars each sample

Göbekli Tepe started in the site’s ‘rock garden’. people were eating, archaeologists are turn- in an oven under controlled conditions.

That’s the name archaeologists dismissively ing to previously ignored sources of evidence, She than magnifies the crispy results by 750

gave a nearby field where they dumped basalt such as charred bits of food. They’re the mis- to 1,000 times to identify the tell-tale changes

grinding stones, limestone troughs and other takes of the past: stews and porridge left on in cell structure caused by different cooking

large pieces of worked stone found amid the the fire for too long, or bits of bread dropped processes. Whether boiled or fresh, ground

rubble. in the hearth or burnt in the oven. “Anyone or whole, dried or soaked, the grains all look

As excavations continued over the past two who’s cooked a meal knows sometimes it different at high magnification. Baking bread

decades, the collection of grinding stones burns,” says Lucy Kubiak-Martens, an archae- leaves tell-tale bubbles behind, for example,

quietly grew, says Dietrich. “Nobody thought obotanist working for BIAX Consult Biological whereas boiling grain before charring it gelat-

about them.” When she started cataloguing Archaeology & Environmental Reconstruction inizes the starch, Valamoti says. “And we can

them in 2016, she was stunned at the sheer in Zaandam, the Netherlands. see all that under the scanning electron micro-

numbers. The ‘garden’ covered an area the size Until the past few years, these hard-to-an- scope.”

of a football field, and contained more than alyse remnants of ruined meals were rarely Comparing the ancient samples with her

10,000 grinding stones and nearly 650 carved given a second look. “It’s just a difficult modern experiments, Valamoti has been

stone platters and vessels, some big enough to material. It’s fragile, ugly stuff,” says Andreas able to go beyond identifying plant species to

hold up to 200 litres of liquid. Heiss, an archaeobotanist at the Austrian Acad- reconstruct the cooking methods and dishes

“No other settlement in the Near East has emy of Sciences in Vienna. “Most researchers of ancient Greece. There is evidence that peo-

so many grinding stones, even in the late Neo- just shied away.” Pottery sherds encrusted with ple in the region have been eating bulgur for at

lithic, when agriculture was already well-es- food remains were cleaned off or discarded least 4,000 years4. By boiling barley or wheat

tablished,” Dietrich says. “And they have a as ‘crud ware’, and charred bits of food were and then drying it for storage and quick rehy-

whole spectrum of stone pots, in every think- dismissed as unanalysable ‘probable food’ and dration later, “you could process the harvest in

able size. Why so many stone vessels?” She shelved or thrown out. bulk and take advantage of the hot sun”, Valam-

suspected that they were for grinding grain The first step towards changing that oti says. “Then you can use it throughout the

Nature | Vol 594 | 24 June 2021 | 489

©

2

0

2

1

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

Feature

year. It was the fast food of the past.” the extraction of bacterial DNA from the part of a larger trend in archaeology to look

Other researchers are also pursuing ancient dental plaque of Neanderthals, including a at household activities and daily lives. “Essen-

cooking mistakes. Charred food remains “are 100,000-year-old individual from what is tially, we’re trying to figure out what kind of

providing us with direct evidence of food”, says now Serbia. The species they found included information you can find out about people

Amaia Arranz-Otaegui, an archaeobotanist at some that specialized in breaking down starch who have never had histories written about

the Paris Museum of Natural History. “That’s into sugars, supporting the idea that Neander- them,” says Sarah Graff, an archaeologist at

revolutionary. It’s an unprecedented source thals had already adapted to a plant-rich diet8. Arizona State University in Tempe.

of information.” Plaque on the teeth of early modern humans In the past, when researchers found plant

In the past, it has been difficult for research- shared a similar bacterial profile, providing remains at archaeological sites, they often con-

ers to find hard evidence that our distant more evidence to suggest that they were eat- sidered them as accidental ‘ecofacts’ — natural

ancestors ate plants. “We’ve always suspected ing starchy plants. objects, such as seeds, pollen and burnt wood,

starch was in the diet of early hominins and The finds push back against the idea that that offer evidence for what kind of plants

early Homo sapiens, but we didn’t have the our ancestors spent their time sitting around grew in a region. But there has been a shift

evidence,” says Kubiak-Martens. campfires mostly chewing on mammoth towards treating food remains as evidence

Genetic data support the idea that people steaks. It’s an idea that has penetrated pop- of an activity that required craft, intent and

were eating starch. In 2016, for example, genet- ular culture, with proponents of the palaeo skill. “Prepared food needs to be looked at as

icists reported5 that humans have more copies diet arguing that grains, potatoes and other an artefact first and a species second,” Fuller

of the gene that produces enzymes to digest says. “Heated, fermented, soaked — making

starch than do any of our primate relatives. food is akin to making a ceramic vessel.”

“Humans have up to 20 copies, and chimpan- And, as researchers increasingly collaborate

zees have 2,” says Cynthia Larbey, an archae-

obotanist at the University of Cambridge, UK.

The old-fashioned to compare ancient remains, they’re finding

remarkable similarities across time and cul-

That genetic change in the human lineage idea that hunter- tures. At Neolithic sites in Austria dating back

helped to shape the diet of our ancestors,

and now us. “That suggests there’s a selective

gatherers didn’t eat more than 5,000 years, for example, archaeol-

ogists found unusually shaped charred crusts.

advantage to higher-starch diets for Homo starch is nonsense.” It was as though the contents of a large jar or

sapiens.” pot had been heated until the liquid burned

To find supporting evidence in the archae- off, and the dried crust inside began to burn.

ological record, Larbey turned to cooking starchy foods have no place on our plates The team’s first guess was that the crusts were

hearths at sites in South Africa dating back because our hunter-gatherer ancestors didn’t from grain storage jars destroyed in a fire. But

120,000 years, picking out chunks of charred evolve to eat them. under the scanning electron microscope, the

plant material — some the size of a peanut. But it has become clear that early humans cell walls of individual grains looked unusually

Under the scanning electron microscope, she were cooking and eating carbs almost as soon thin — a sign, Heiss says, that something else

identified cellular tissue from starchy plants6 as they could light fires. “The old-fashioned was going on.

— the earliest evidence of ancient people cook- idea that hunter-gatherers didn’t eat starch After comparing the Austrian finds to sim-

ing starch. “Right through from 120,000 to is nonsense,” says Fuller. ilar crusts found in Egyptian breweries from

65,000 years ago, they’re cooking roots and around the same time, Heiss and Valamoti con-

tubers,” Larbey says. The evidence is remark- Invisible cooks cluded that the thin cell walls were the result

ably consistent, she adds, particularly com- The push to better understand how people of germination, or malting, a crucial step in

pared with animal remains from the same site. were cooking in the past also means paying the brewing process. These early Austrian

“Over time they change hunting techniques more attention to the cooks themselves. It’s farmers were brewing beer9. “We ended up

and strategies, but still continue to cook and

eat plants.”

Early humans probably ate a balanced diet,

leaning on starchy plants for calories when

game was scarce or hard to hunt. “And being

able to find carbohydrates as they moved into

new ecologies would have provided important

staple foods,” Larbey adds.

Evidence suggests that plants were popular

among Neanderthals, too. In 2011, Amanda

Henry, a palaeoanthropologist now at Leiden

University in the Netherlands, published her

findings from dental plaque picked from the

teeth of Neanderthals who were buried in Iran

and Belgium between 46,000 and 40,000

years ago. Plant microfossils trapped and pre-

served in the hardened plaque showed that

they were cooking and eating starchy foods

including tubers, grains and dates7. “Plants are

ubiquitous in our environment,” Henry says,

“and it’s no surprise we put them to use.”

JOE ROE

In May, Christina Warinner, a palaeo

geneticist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Amaia Arranz-Otaegui (right) and colleagues found evidence of bread from 14,500 years ago.

Massachusetts, and her colleagues reported

490 | Nature | Vol 594 | 24 June 2021

©

2

0

2

1

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

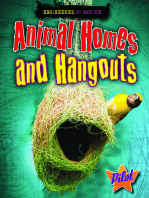

FAST FOOD OF THE BRONZE AGE stones piled in Göbekli Tepe’s rock garden,

Bulgur-like grain fragments found at a roughly 4,000-year-old site in northern Greece have Dietrich could show that fine-ground bread

microscopic features resembling those of modern samples that had been parboiled and charred

in experiments. The ancient grain was apparently boiled then dried to speed up later cooking.

flour was the exception. In a 2020 study11, she

argues people there were mostly grinding

grain coarsely, just enough to break up its

SOULTANA MARIAVALAMOTI ET AL./J. ARCHAEOL. SCI.

tough outer layer of bran and make it easy to

boil and eat as porridge or ferment into beer.

To test the theory, Dietrich commissioned

a stonemason to carve a replica of a 30-litre

stone vat from Göbekli Tepe. In 2019, she and

her team successfully cooked porridge using

heated stones, carefully recording and timing

50 µm

each step of the process. They also brewed a

200 µm

Scanning electron Smooth, almost glassy, surface Neolithic beer from hand-ground germinated

microscope reveals surface indicates that the grain gelatinized, grain, or malt, in the open vessel. The results

textures of grain fragment. perhaps from parboiling.

were “a bit bitter, but drinkable”, Dietrich says.

“If you’re thirsty in the Neolithic.”

with something completely different” from another overlooked part of the ancient diet. From the grind stones and other plant-pro-

the earlier hypotheses, Heiss says. “Several Because raw greens and vegetables are even cessing tools at Göbekli Tepe, a picture is now

lines of evidence really interlocked and fell harder to find in the archaeological record emerging for what was going on there 12,000

into place.” than cooked seeds and grains, Kubiak-Mar- years ago. Rather than just starting to experi-

Bread, it seems, goes even further back. tens calls them the “missing link” in knowl- ment with wild grains, the monument builders

Arranz-Otaegui was working at a 14,500-year- edge about ancient diets. “There’s no way to were apparently proto-farmers, already famil-

old site in Jordan when she found charred bits prove green leaves were eaten from charred iar with the cooking possibilities grain offered

of ‘probable food’ in the hearths of long-ago remains,” Kubiak-Martens says. “But you would despite having no domesticated crops. “These

hunter-gatherers. When she showed scanning be surprised at how much green vegetables are the best grinding tools ever, and I’ve seen

electron microscope images of the stuff to Lara are in human coprolites”, or preserved faeces. a lot of grindstones,” Dietrich says. “People

González Carretero, an archaeobotanist at the Kubiak-Martens got a grant in 2019 to look at at Göbekli Tepe knew what they were doing,

Museum of London Archaeology who works on 6,300-year-old palaeofaeces preserved at and what could be done with cereals. They’re

evidence of bread baking at a Neolithic site in wetland sites in the Netherlands, which she beyond the experimentation phase.”

Turkey called Çatalhöyük, both researchers hopes will reveal everything prehistoric farm- Her experiments are shifting the way archae-

were shocked. The charred crusts from Jordan ers there had on their dinner tables. ologists understand the site — and the period

had tell-tale bubbles, showing they were burnt when it was built. Their initial interpretations

pieces of bread10. Recreating ancient meals made the site sound a bit like a US college fra-

Most archaeologists have assumed that The quest to understand ancient diets has led ternity house: lots of male hunters on a hilltop,

bread didn’t appear on the menu until after some researchers to take extreme measures. washing down barbecued antelope with vats

grain had been domesticated — 5,000 years That’s the case with Göbekli Tepe, which has of lukewarm beer at occasional celebrations.

after the cooking accident in question. So it yielded very few organic remains that could “Nobody really thought of the possibility of

seems that the early bakers in Jordan used wild provide clues to the prehistoric plant-based plant consumption” on a large scale, Dietrich

wheat. meals there. So Dietrich has tried innovative says.

The evidence provides crucial clues to the thinking — and a lot of elbow grease. Her In a study late last year12, Dietrich argues the

origins of the Neolithic revolution, when peo- approach has been to recreate the tools people ‘barbecue and beer’ interpretation is way off.

ple began to settle down and domesticate used to make food, not the dishes themselves. The sheer number of grain-processing tools at

grain and animals, which happened at differ- In her airy lab on a tree-lined street in Ber- Göbekli Tepe suggest that even before farming

ent times in various parts of the world. Before lin, Dietrich explains her time-consuming and took hold, cereals were a daily staple, not just

farming began, a loaf of bread would have been physically demanding process. Starting with part of an occasional fermented treat.

a luxury product that required time-consum- a replica grindstone — a block of black basalt

ing and tedious work gathering the wild grain the size of a bread roll that fits neatly in the Andrew Curry is a science journalist in Berlin.

needed for baking. That hurdle could have palm of her hand — she photographs it from

helped to spur crucial changes. 144 different angles.

Arranz-Otaegui’s research suggests that — After spending eight hours grinding four

at least in the Near East — demand for bread kilograms of heirloom einkorn wheat kernels, 1. Dietrich, L. et al. PLoS ONE 14, e0215214 (2019).

might have been a factor in driving people Dietrich photographs the stone again. A soft- 2. Heun, M. et al. Science 278, 1312–1314 (1997).

to attempt to domesticate wheat, as they ware program then produces 3D models from 3. Valamoti, S. M. Veget. Hist. Archaeobot. 11, 17–22 (2002).

4. Valamoti, S. M. et. al. J. Archaeol. Sci. 128, 105347 (2021).

looked for ways to ensure a steady supply the two sets of pictures. Her experiments have 5. Inchley, C. E. et al. Sci. Rep. 6, 37198 (2016).

of baked goods. “What we are seeing in Jor- shown that grinding fine flour for baking bread 6. Larbey, C., Mentzer, S. M., Ligouis, B., Wurz, S. &

dan has implications for bigger processes. leaves a different finish on the stones from pro- Jones, M. K. J. Hum. Evol. 131, 210–227 (2019).

7. Henry, A. G., Brooks, A. S. & Piperno, D. R. Proc. Natl Acad.

What drove the transition to agriculture is ducing coarsely ground grain that is ideal for Sci. USA 108, 486–491 (2011).

one of the fundamental questions in archae- boiling as porridge or brewing beer. 8. Fellows Yates, J. A. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118,

e2021655118 (2021).

ology,” Arranz-Otaegui says. “This shows And after handling thousands of grind-

9. Heiss, A. G. et al. PLoS ONE 15, e0231696 (2020).

hunter-gatherers were using cereals.” stones, she is often able to identify what they 10. Arranz-Otaegui, A., Gonzalez Carretero, L., Ramsey, M. N.,

The next frontier for archaeobotanists is were used for by touch. “I touch the stones to Fuller, D. Q. & Richter, T. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115,

7925–7930 (2018).

prehistoric salad bars. Researchers are work- feel for flattening,” she says. “Fingers can feel

11. Dietrich, L. & Haibt, M. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 33, 102525

ing on ways to look for the remains of food changes at the nano level.” By comparing the (2020).

that wasn’t cooked, such as leafy greens, wear patterns on her modern replicas to the 12. Dietrich, L. et al. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 34, 102618 (2020).

Nature | Vol 594 | 24 June 2021 | 491

©

2

0

2

1

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

You might also like

- How Did Ancient Humans Learn To Count?: FeatureDocument4 pagesHow Did Ancient Humans Learn To Count?: FeatureAnahí TessaNo ratings yet

- Nature aDNA Archaeology Vs Genetics PDFDocument4 pagesNature aDNA Archaeology Vs Genetics PDFMonika MilosavljevicNo ratings yet

- Urine To Save The WorldDocument5 pagesUrine To Save The WorldmiguelNo ratings yet

- MayanBones Nature 0219 PDFDocument4 pagesMayanBones Nature 0219 PDFAnthony CerlaNo ratings yet

- The Quest For An All-Inclusive Human GenomeDocument4 pagesThe Quest For An All-Inclusive Human GenomeAnahí TessaNo ratings yet

- Prova Selecao Ingles PG-EIA 2021-2osemDocument4 pagesProva Selecao Ingles PG-EIA 2021-2osemGabriel Cristofoletti DiorioNo ratings yet

- Articulo NatureDocument2 pagesArticulo Natureivan.quijano.aranibarNo ratings yet

- Nature MagazineDocument3 pagesNature MagazineArdian Kris BramantyoNo ratings yet

- Sydney Brenner: Molecular Biology Pioneer DiesDocument3 pagesSydney Brenner: Molecular Biology Pioneer DiesIstanislao Dimitrova EluvoitieNo ratings yet

- The Science That Never Has Been CitedDocument4 pagesThe Science That Never Has Been CitedCuentaLibrosScribdNo ratings yet

- Paper MillsDocument4 pagesPaper Millsalvin susetyoNo ratings yet

- Corrigenda: Corrigendum: Pramel7 Mediates Ground-State Pluripotency Through Proteasomal-Epigenetic Combined PathwaysDocument1 pageCorrigenda: Corrigendum: Pramel7 Mediates Ground-State Pluripotency Through Proteasomal-Epigenetic Combined PathwaysnugrahoneyNo ratings yet

- Food System PrioritiesDocument3 pagesFood System Prioritiesbubursedap jbNo ratings yet

- Importance of Integrating Spiritual, Existential, Religious, and Theological Components in Psychedelic-Assisted TherapiesDocument6 pagesImportance of Integrating Spiritual, Existential, Religious, and Theological Components in Psychedelic-Assisted TherapiesKenzo SunNo ratings yet

- Wine, Water, Oil and Spit: Books & Arts CommentDocument3 pagesWine, Water, Oil and Spit: Books & Arts CommentBEN DUNCAN MALAGA ESPICHANNo ratings yet

- 10 People - NatureDocument9 pages10 People - NaturePaulo César de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- 10 - ING - Cartilla Ingles Decimo Tercer Periodo InglesDocument13 pages10 - ING - Cartilla Ingles Decimo Tercer Periodo InglesvivianegubuNo ratings yet

- The Race To Understand Colombia's Exeption BiodiversityDocument4 pagesThe Race To Understand Colombia's Exeption BiodiversityMinh Khôi QuáchNo ratings yet

- The Hunt For A Healthy Microbiome: OutlookDocument3 pagesThe Hunt For A Healthy Microbiome: OutlookLindo PulgosoNo ratings yet

- Cities - Try To Predict SuperspreadingDocument4 pagesCities - Try To Predict SuperspreadingJavier BlancoNo ratings yet

- TEst EnglezaDocument9 pagesTEst Englezajeo mamaNo ratings yet

- Criteria For AutorsDocument3 pagesCriteria For Autorsviviana84No ratings yet

- The Scientists Who Publish A Paper Every Five DaysDocument3 pagesThe Scientists Who Publish A Paper Every Five DaysKarol MachadoNo ratings yet

- Technology Recorded History Prehistoric Hominids Stone ToolsDocument13 pagesTechnology Recorded History Prehistoric Hominids Stone ToolsAnna Maria.No ratings yet

- The Power of Diversity.Document4 pagesThe Power of Diversity.Jonas JacobsenNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument35 pagesUntitledSimon VotteroNo ratings yet

- Geologic Time ScaleDocument30 pagesGeologic Time ScaleAnonymous IgPWVyNo ratings yet

- Scientia Experia 6Document6 pagesScientia Experia 6ramsiriusNo ratings yet

- A World Without Cause and Effect: Logic-Defying Experiments Into Quantum Causality Scramble The Notion of Time ItselfDocument3 pagesA World Without Cause and Effect: Logic-Defying Experiments Into Quantum Causality Scramble The Notion of Time ItselfWalterHuNo ratings yet

- A New History of EthiopiaDocument400 pagesA New History of EthiopiaTayeNo ratings yet

- Taxonomy AnarchyDocument3 pagesTaxonomy AnarchyRuth Yanina Valdez MisaraymeNo ratings yet

- Garnet & Christidis 2017Document3 pagesGarnet & Christidis 2017Gerard QuintosNo ratings yet

- Nature - The Hydrogen RevolutionDocument4 pagesNature - The Hydrogen RevolutionOUSSAMA BEN OMARNo ratings yet

- KathmanduDocument10 pagesKathmandupratiksha.aryaixNo ratings yet

- Mediterranean SeaDocument6 pagesMediterranean SeaJonahNo ratings yet

- Futures: Don't Feed The PhysicistsDocument2 pagesFutures: Don't Feed The PhysicistsDominic GreenNo ratings yet

- 2017 HerendeenEtAL Angiosperms LectureFossilPlants PalynologyDocument8 pages2017 HerendeenEtAL Angiosperms LectureFossilPlants PalynologyJavier PautaNo ratings yet

- Rangoli: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument5 pagesRangoli: Jump To Navigation Jump To Searchhareram panchalNo ratings yet

- Could An Infection Trigger Alzheimer's Disease?Document5 pagesCould An Infection Trigger Alzheimer's Disease?BereRodriguezNo ratings yet

- Classroom OrientationDocument32 pagesClassroom OrientationTin Cabrera-LansanganNo ratings yet

- Presentation 3Document1 pagePresentation 3api-3698735No ratings yet

- KunalDocument36 pagesKunalSubhash KumarNo ratings yet

- WT SanitarywareDocument84 pagesWT SanitarywarePOOJA YOGENDRANo ratings yet

- What Stars Are Made Of-The Life of Cecilia Payne-GaposchkinDocument2 pagesWhat Stars Are Made Of-The Life of Cecilia Payne-GaposchkinlaurakaiohNo ratings yet

- Portrait of A MemoryDocument3 pagesPortrait of A MemoryprinceNo ratings yet

- The Pain GapDocument3 pagesThe Pain GapSILVANA GISELLE LLANCAPAN VIDALNo ratings yet

- The Coronavirus Will Become Endemic: FeatureDocument3 pagesThe Coronavirus Will Become Endemic: FeatureNawdir ArtupNo ratings yet

- W-Boson NewsDocument2 pagesW-Boson News8q74ndhrhxNo ratings yet

- Kami Export - 1688 - 001 PDFDocument4 pagesKami Export - 1688 - 001 PDFAlexander RussellNo ratings yet

- Comment: Biodiversity Needs Every Tool in The Box: Use OecmsDocument4 pagesComment: Biodiversity Needs Every Tool in The Box: Use Oecmsmudhof05No ratings yet

- Reboot For The AI Revolution: CommentDocument4 pagesReboot For The AI Revolution: CommentAaron YangNo ratings yet

- Red Zone Report 2018Document211 pagesRed Zone Report 2018YunquanNo ratings yet

- Scratch and Claw EncountersDocument1 pageScratch and Claw EncountersWilliam RobinsonNo ratings yet

- 01 Control Valve PicturesDocument27 pages01 Control Valve PicturesNyoman RakaNo ratings yet

- Finals PortfolioDocument21 pagesFinals PortfolioERIN JOY RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- d41586 018 03790 5Document2 pagesd41586 018 03790 5OmbralastNo ratings yet

- Covid and KidsDocument3 pagesCovid and Kidsumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Origine Etruschi Suppl 2Document18 pagesOrigine Etruschi Suppl 2umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Intramural Burials Catal HuyukDocument29 pagesIntramural Burials Catal Huyukumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Oι σημερινοί Έλληνες όμοιοι με τους πληθυσμούς του Β. Αιγαίου του 2.000 π.Χ.Document44 pagesOι σημερινοί Έλληνες όμοιοι με τους πληθυσμούς του Β. Αιγαίου του 2.000 π.Χ.ARISTEIDIS VIKETOSNo ratings yet

- End Life Decisions Early Human Development 2009Document5 pagesEnd Life Decisions Early Human Development 2009umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Anatolia SkourtaniotiDocument47 pagesAnatolia Skourtaniotiumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Success Maternal Feeding VLBWDocument2 pagesSuccess Maternal Feeding VLBWumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Bone Marrow Transplantation RdsDocument4 pagesBone Marrow Transplantation Rdsumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- FA Terapia PrystowskyDocument11 pagesFA Terapia Prystowskyumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Acilcarnitine e AA Nel LADocument4 pagesAcilcarnitine e AA Nel LAumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- End Life Decisions Early Human Development 2009Document5 pagesEnd Life Decisions Early Human Development 2009umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- End of Life Jama 2000Document9 pagesEnd of Life Jama 2000umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- PPEpidemiol 97Document13 pagesPPEpidemiol 97umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Parental Visiting, Communication, and Participation in Ethical Decisions: A Comparison of Neonatal Unit Policies in EuropeDocument8 pagesParental Visiting, Communication, and Participation in Ethical Decisions: A Comparison of Neonatal Unit Policies in Europeumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- IMS Acta PaediatrDocument2 pagesIMS Acta Paediatrumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Growth HormoneDocument2 pagesGrowth Hormoneumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Treatment Choices J Ped 2000Document9 pagesTreatment Choices J Ped 2000umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Family Centered Neonatal CareDocument2 pagesFamily Centered Neonatal Careumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- PPEpidemiol 97Document13 pagesPPEpidemiol 97umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- End of Life Lancet 2000Document7 pagesEnd of Life Lancet 2000umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Parental Visiting ADCDocument8 pagesParental Visiting ADCumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Mortality in ItalyDocument1 pageNeonatal Mortality in Italyumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- PPEpidemiol 97Document13 pagesPPEpidemiol 97umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Bone Marrow Transplantation RdsDocument4 pagesBone Marrow Transplantation Rdsumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- End Life Decisions Early Human Development 2009Document5 pagesEnd Life Decisions Early Human Development 2009umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Family Centered Neonatal CareDocument2 pagesFamily Centered Neonatal Careumberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- End of Life Jama 2000Document9 pagesEnd of Life Jama 2000umberto de vonderweidNo ratings yet

- Archeology N BotanyDocument7 pagesArcheology N BotanyKlinsman NunesNo ratings yet

- Marinova Plant Economy and Land Use in Middle EgyptDocument18 pagesMarinova Plant Economy and Land Use in Middle EgyptDiana BujaNo ratings yet

- Garcia-Granero Etal 2017 QIDocument12 pagesGarcia-Granero Etal 2017 QIMaria LymperakiNo ratings yet

- Archaeobotany in Turkey A Review of Current ResearchDocument7 pagesArchaeobotany in Turkey A Review of Current ResearchAlireza EsfandiarNo ratings yet

- Nubia Handbook Final MsDocument40 pagesNubia Handbook Final MsMmabutsi MathabatheNo ratings yet

- The Study of Archaeobotanical RemainsDocument15 pagesThe Study of Archaeobotanical RemainsEugen Popescu100% (1)

- Balcanica XLIII 2013Document372 pagesBalcanica XLIII 2013mvojnovic66No ratings yet

- Alonso Plant Use and Storage Veget Hist Archaeobot (2016)Document15 pagesAlonso Plant Use and Storage Veget Hist Archaeobot (2016)Martin Palma UsuriagaNo ratings yet

- John M. Marston: Professional AppointmentsDocument21 pagesJohn M. Marston: Professional AppointmentsJohn MarstonNo ratings yet

- Lepofsky y Lyons 2003Document15 pagesLepofsky y Lyons 2003valentinaNo ratings yet

- Paleoethnobotany Third Edition 2015Document514 pagesPaleoethnobotany Third Edition 2015jptereso100% (1)

- The Development of Weed Vegetation in The Pannonian Basin As Seen in The Archaeobotanical RecordsDocument14 pagesThe Development of Weed Vegetation in The Pannonian Basin As Seen in The Archaeobotanical RecordsLaszlo NyariNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument31 pagesPDFTarek AliNo ratings yet

- An Archaeobotanical Analysis of The Isla PDFDocument19 pagesAn Archaeobotanical Analysis of The Isla PDFAna StNo ratings yet

- PearsallDocument46 pagesPearsallManuel AndradeNo ratings yet

- Ethnobotany For Beginners Springer InternationDocument79 pagesEthnobotany For Beginners Springer Internationerino n100% (1)

- Balcanica XLIII 2012 PDFDocument372 pagesBalcanica XLIII 2012 PDFPetrokMaloyNo ratings yet

- Hallucinogenis Snuff CojobaDocument17 pagesHallucinogenis Snuff CojobaNavila ZayerNo ratings yet

- Plants, Politics and Empire in Ancient Rome - Bryn Mawr Classical ReviewDocument4 pagesPlants, Politics and Empire in Ancient Rome - Bryn Mawr Classical ReviewGorriónNo ratings yet

- Caracuta2020 Article OliveGrowingInPugliaSoutheasteDocument26 pagesCaracuta2020 Article OliveGrowingInPugliaSoutheasteEdoardo VanniNo ratings yet

- Agriculture: Definition and Overview: January 2014Document11 pagesAgriculture: Definition and Overview: January 2014darthvader909No ratings yet

- Sill Ar 2013Document26 pagesSill Ar 2013Ei FaNo ratings yet

- Roman and Medieval Crops in The Iberian Peninsula - A First Overview of Seeds and Fruits From Archaeological SitesDocument18 pagesRoman and Medieval Crops in The Iberian Peninsula - A First Overview of Seeds and Fruits From Archaeological SitesSofia SerraNo ratings yet

- Ethnobotany Scope and ImportanceDocument43 pagesEthnobotany Scope and ImportanceZafar Khan100% (1)

- Balcanica XLVIDocument463 pagesBalcanica XLVIHristijan CvetkovskiNo ratings yet

- Merlin M.D. "Archaeological Evidenct of Pcychoactive Plant Using"Document29 pagesMerlin M.D. "Archaeological Evidenct of Pcychoactive Plant Using"shu_sNo ratings yet

- Recent Research in PaleoethnobotanyDocument49 pagesRecent Research in PaleoethnobotanyHannah Fernandes100% (1)

- Terramaras On The Po PlainDocument18 pagesTerramaras On The Po Plainsmitrovic482100% (1)

- Price Bar Yosef 2011Document13 pagesPrice Bar Yosef 2011Claudio WandeNo ratings yet

- (Blackwell Companions To The Ancient World) David Hollander, Timothy Howe - A Companion To Ancient Agriculture-Wiley-Blackwell (2020) PDFDocument738 pages(Blackwell Companions To The Ancient World) David Hollander, Timothy Howe - A Companion To Ancient Agriculture-Wiley-Blackwell (2020) PDFCarlos Adolfo100% (1)