Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scjohn N Inghamsc Italicmaking Iron and Steel Independent Mills 1992

Uploaded by

AmlaanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Scjohn N Inghamsc Italicmaking Iron and Steel Independent Mills 1992

Uploaded by

AmlaanCopyright:

Available Formats

United States

1291

cracker, who intentionally misspelled many of his successful on paper only because the high number of

words, and who used quaint anecdotes and personal convictions concealed lenient sentencing. The record

and family reminiscences to make his points, was of prosecution of outlaw "cowboys" and other viola-

humor. Parker misses a great opportunity to study tors of federal laws in Arizona was mixed, with some

Arp's relationship to his readers by failing to specu- successes but continuing citizen resentment. Gener-

late about why his audience found his work so funny. ally Cresswell blames unimpressive results on inade-

Arp was his day's Lewis Grizzard, another cranky quate congressional appropriations for federal law

southern satirist, and both Grizzard and Arp owed enforcement; attorneys general who rarely assisted

their popularity far less to their ideas than to the the district attorneys with useful legal advice in diffi-

unique ability of humor to make audiences feel cult cases; and federal district judges who reflected

superior and secure. local attitudes rather than national standards. The

TED OWNBY bottom line, though, was the unwillingness, some-

University of Mississippi times forced by violence and intimidation, of local

citizens to cooperate as witnesses or jurors.

Cresswell reveals how political history, even admin-

STEPHEN CRESSWELL. Mormons and Cowboys, Moonshin-

istrative history, is intimately linked to social history.

ers and Klansmen: Federal Law Enforcement in the South

He demonstrates that authority and law reflect both

and West, 1870-1893. Tuscaloosa: University of Ala-

the conceptions and activities of representatives of

bama Press. 1991. Pp. viii, 323. $35.95.

the state at the top and the customs and responses of

citizens at the bottom. His book will be of interest to

Stephen Cresswell, although not explicitly addressing

historians of state development as well as southern

the issues of political science state-building theory,

and western specialists.

deepens American historians' current effort to "bring

WILBUR R. MILLER

the state back in." He examines a major agency of the

State University of New York,

national government, the Department of Justice, and

Stony Brook

its efforts to enforce federal law in the face of

widespread citizen resistance. He reveals the limits of

the "center's" ability to extend its authority to the JOHN N. INGHAM. Making Iron and Steel: Independent

"periphery" as well as the conditions under which Mills in Pittsburgh, 1820-1920. (Historical Perspec-

national authority was successfully asserted in the late tives on Business Enterprise Series.) Columbus: Ohio

nineteenth century. State University Press. 1991. Pp. xi, 297. $45.00.

Beginning with the Civil War, the number of

legally defined federal crimes steadily increased. The In this volume John N. Ingham highlights the vitality

Department of Justice's marshals arrested violators, of small and mid-sized manufacturing firms in the

district attorneys prosecuted them, and district judges nation's most dynamic industry. Frustrated by the

heard federal criminal cases. Other agencies, partic- prevailing Chandlerian preoccupation with huge,

ularly the post office, treasury, and army, worked capital intensive, integrated mass producers, Ingham

with Justice to track down and punish federal crimi- counters with a close look at the resilient independent

nals. iron and steel firms in Pittsburgh between 1820 and

There have been studies of episodes and specific 1920. These moderate-sized businesses found prod-

agencies of federal law enforcement but no general uct and market niches that allowed them to survive

history of the Department of Justice since Homer and even multiply in the face of an organizational and

Cummings and Carl McFarland's Federal Justice technological revolution. Masters of the local econ-

(1937). Cresswell's book is not a comprehensive his- omy as early as the 1850s, the iron barons and their

tory but is valuable because it focuses on the officials mercantile partners became Pittsburgh's elite. A self-

on the front lines of particularly difficult enforcement conscious upper class, they jealously guarded entry

campaigns and how local citizens responded to their into their social world. Rising with the Republican

efforts. Party, this elite held the reins of political power; when

Cresswell's case studies examine two southern waves of immigrants flooded the city, they used

states and two western territories. He chooses the progressive rhetoric and reforms to maintain and

South and West because citizen resistance to distant even extend their dominance. In short, the barons

central authority was greatest in these peripheral "remained lords of all they surveyed" (p. 190).

regions. The only clearly successful assertion of na- This book draws on two sets of mid-nineteenth to

tional authority was the crackdown on Mormon po- early twentieth-century data: a listing of all the inde-

lygamy in Utah, because it was backed by widespread pendent mills, their choice of technique, and volume

condemnation among non-Mormons, congressional of output; and a roster of all mill owners, their

determination to outlaw the practice, and presidential representation in selected social registers, and an

will to enforce the laws. Battling the Ku Klux Klan in assigned family rank. The roster of mill owners

northern Mississippi was a losing war against vio- divides the mill families into elite, core, noncore, and

lence. Prosecuting Tennessee moonshiners looked marginal categories based on a method devised and

AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW OCTOBER 1992

1292 Reviews of Books

described by Ingham in an earlier book, The Iron the company were the norm. Anticompany feelings

Barons (1978). Armed with this information, Ingham and anticompany behavior such as strikes and vio-

measures the persistence of firms and, with selected lence were the aberrations.

examples, explains how the independent firms sur- Arranged topically rather than chronologically, the

vived. After two bruising experiences, independent study is divided into four parts. Part 1 discusses

iron and steel manufacturers avoided head-to-head preindustrial Appalachia that, according to the au-

competition with Carnegie Steel. Because Andrew thor, was a worse place to live and work than the

Carnegie did not benefit from economies of scale in company town. Part 2 explores the coming of the coal

puddling, crucible steelmaking, or the open hearth companies and the making of the company town. Part

process, smaller, nonintegrated firms could profitably 3 examines the union. Part 4 looks at coal towns as

employ these techniques to supply niche markets with social and cultural communities and the activities of

highly specialized wares. These were the typical iron the miners and their families within them.

The book has some commendable aspects. Shiffiett

and steel firms of their day, accounting for more of

makes extensive use of both oral histories and coal

Pittsburgh's employment and productive capacity

company records for his research. Especially well told

than the newly formed U.S. Steel.

and documented are the rise of several southern

More than scale separated these iron barons from

Appalachian coal companies and the early methods

the Carnegie men. While Carnegie engaged in rabid

of mining coal.

antiunionism that led to violence, the independents

As a revisionist study, however, the book is weak.

grudgingly accepted Amalgamated unions and en-

There is no effort to reinterpret the dynamics of the

joyed relatively peaceful labor relations. This en- coal town or the interaction between company offi-

trenched elite shunned Carnegie and his lieutenants, cials and coal miners. Shiffiett merely tells what was

excluding them from Pittsburgh's social and cultural good about the towns and leaves out the bad: the

swirl. The Carnegie interests avoided local politics, deadly mine explosions, the unsanitary conditions,

perhaps because they knew that the entrenched elite the mine guard system and the beating and murders

would blunt demands for government regulation of of union organizers, black lists and housing contracts,

business and expenditures for social welfare. coal company scrip and monopolistic company store

This volume owes much to Philip Scranton's pio- prices, the companies' refusal to put checkweighmen

neering book Proprietary Capitalism (1983). It demon- at their mines, and all those other things that pro-

strates once again that industrialization involved duced Bloody Mingo, the Armed March on Logan,

more than the simple progression of scale and tech- the Matewan Massacre, Bloody Harlan, and other

nique. To re-create our history we need to study small events that characterized the Appalachian coal fields

businesses as well as large ones. But we also need to until the coming of the union in the 1930s.

recognize that the independent iron and steel enter- In trying to make his revisionist case about life and

prises were not typical small businesses. With their culture in the coal camps, Shiffiett leans heavily on

demands for inanimate power, sizable physical plant, oral histories. "Most striking about former miners

and working capital, iron firms discouraged entry by and their families are their positive recollections of

those who possessed only luck, pluck, and diligence. life and work in [the] company town" (p. 150), he

Escalating costs of entry limited the number of po- writes, and the "perspectives of former miners on life

tential entrants to those who had ready access to in the company town sometimes contrast sharply with

capital, while retained earnings and intermarriage conventional images of company towns" (p. xiv).

enabled the pre—Civil War elite families to bequeath Oral histories give a nostalgia about company towns

their positions to the next generation and beyond. that belies the actions of their inhabitants: open and

DIANE LINDSTROM expressed opposition and hostility to the system. The

University of Wisconsin, contradiction between the nostalgia and the reality is

Madison certainly worthy of exploration. Shiffiett, however,

ignores the miners' protests against the system and

dwells instead on their fond memories.

CRANDALL A. SHIFFLETT.Coat Towns: Life, Work, and The author decries "generalizations about the 'av-

Culture in Company Towns of Southern Appalachia, erage' company town" (p. 9), but his book is filled with

1880-1960. Knoxville: University of Tennessee sweeping generalizations and, too often, he provides

Press. 1991. Pp. xx, 259. no supporting evidence for the broad assertions.

"Goal companies prohibited the use of the church for

This book is intended as a revisionist study of Appa- labor agitation," he contends, "but it is doubtful that

lachian coal company towns. Instead of being oppres- the miners were troubled by that to any great extent"

sive and exploitive, as previous historians claim, coal (p. 197). "There is little evidence that mine work

mining offered the Appalachians work, and company mitigated social prejudice against immigrants and

towns gave them a better life style, Crandall A. blacks" (p. xv). Abundant evidence exists to the

Shiffiett argues. Harmony, a strong sense of commu- contrary of each assertion and other historians have

nity, and positive feelings about both the town and cited it.

AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW OCTOBER 1992

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Metallurgical EngineeringDocument126 pagesMetallurgical EngineeringAmlaanNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- M. Tech. Phy Metallurgy Curriculum Structure 03 March 2016Document45 pagesM. Tech. Phy Metallurgy Curriculum Structure 03 March 2016AmlaanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Tinywow Functional Level Strategies 8772818Document24 pagesTinywow Functional Level Strategies 8772818AmlaanNo ratings yet

- Santa Waj A 2020Document10 pagesSanta Waj A 2020AmlaanNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Huang 2011Document6 pagesHuang 2011AmlaanNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- 10 2307@25067027Document4 pages10 2307@25067027AmlaanNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Ahmed 2013Document14 pagesAhmed 2013AmlaanNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Date of Rāmāyana: Vedveer AryaDocument29 pagesThe Date of Rāmāyana: Vedveer AryaAmlaanNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Xu 2010Document7 pagesXu 2010AmlaanNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Gita-Govinda - Jayadeva - Commentary PrabodhanandaDocument164 pagesGita-Govinda - Jayadeva - Commentary PrabodhanandaAmlaanNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Dokumen - Tips - Sarva Mula TikasDocument5 pagesDokumen - Tips - Sarva Mula TikasAmlaanNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Blackwell 1852Document2 pagesBlackwell 1852AmlaanNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- IskconDocument1 pageIskconAmlaanNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Indian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, ShibpurDocument3 pagesIndian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, ShibpurAmlaanNo ratings yet

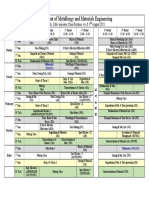

- Department of Metallurgy and Materials Engineering: B. Tech. Odd-Semester Class Routine, W.E.F. 9 August 2021Document1 pageDepartment of Metallurgy and Materials Engineering: B. Tech. Odd-Semester Class Routine, W.E.F. 9 August 2021AmlaanNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Placement Statistic 2020Document3 pagesPlacement Statistic 2020AmlaanNo ratings yet

- Indian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, ShibpurDocument4 pagesIndian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, ShibpurAmlaanNo ratings yet

- Provisional Academic Calendar: Academic Year 2021-22Document3 pagesProvisional Academic Calendar: Academic Year 2021-22AmlaanNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Spouses Roque vs. AguadoDocument14 pagesSpouses Roque vs. AguadoMary May AbellonNo ratings yet

- Vicar International Corp vs. Feb Leasing Case DigestDocument3 pagesVicar International Corp vs. Feb Leasing Case Digestkikhay11No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Legal MaximsDocument18 pagesLegal MaximsDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Hollier v. Rambler Motors AMC LTD (1972)Document5 pagesHollier v. Rambler Motors AMC LTD (1972)Saurabh MisalNo ratings yet

- SSIP SampleDocument6 pagesSSIP SampleAngelo Delgado100% (6)

- Form For Nomination / Cancellation of Nomination / Change of NominationDocument2 pagesForm For Nomination / Cancellation of Nomination / Change of NominationShyamgNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Appointment of TrusteesDocument8 pagesAppointment of TrusteesNaveen PatilNo ratings yet

- Tennessee School Discipline Laws and RegulationsDocument119 pagesTennessee School Discipline Laws and RegulationsBrad ChurchwellNo ratings yet

- UNIT-2 BS-XI RK SinglaDocument36 pagesUNIT-2 BS-XI RK SinglaJishnu Duhan0% (1)

- Transmission Indemnity BondDocument3 pagesTransmission Indemnity BondJose JohnNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Potain MR605Document4 pagesPotain MR605Jhony Espinoza PerezNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesDocument14 pagesDoctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesEmmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciNo ratings yet

- Labor Law UST Golden NotesDocument267 pagesLabor Law UST Golden NotesLeomard SilverJoseph Centron Lim93% (15)

- Visa Application Document GermanyDocument4 pagesVisa Application Document GermanyKrishna MuthaNo ratings yet

- AMLA (RA 9160 As Amended by RA 10365)Document83 pagesAMLA (RA 9160 As Amended by RA 10365)Karina Barretto AgnesNo ratings yet

- Contents of Partnership Deed: 1. NameDocument4 pagesContents of Partnership Deed: 1. NameRizwan AliNo ratings yet

- SPL Reviewer MidtermDocument4 pagesSPL Reviewer MidtermGui Pe100% (1)

- Tort LawDocument3 pagesTort LawChamara SamaraweeraNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila: Chan v. Sec. of Justice, Formaran & PAOCTFDocument7 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila: Chan v. Sec. of Justice, Formaran & PAOCTFJopan SJNo ratings yet

- Football The Legendary Game: Physical EducationDocument20 pagesFootball The Legendary Game: Physical EducationDev Printing SolutionNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- United States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitDocument20 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CSC Vs SojorDocument3 pagesCSC Vs SojorManuel AlamedaNo ratings yet

- PD 957 PDFDocument4 pagesPD 957 PDFInnah MontalaNo ratings yet

- Old Standard ClippingsDocument9 pagesOld Standard Clippings9newsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 26771, September 23, 1927 (Malcolm, J.) - G.R. NO. 83558, February 27, 1989 (Cortes, J.) - G.R. No. 147861 November 18, 2005 (Tiñga, J.)Document2 pagesG.R. No. 26771, September 23, 1927 (Malcolm, J.) - G.R. NO. 83558, February 27, 1989 (Cortes, J.) - G.R. No. 147861 November 18, 2005 (Tiñga, J.)DONCHRISTIAN SANTIAGONo ratings yet

- BSL 605 - Lecture 3 PDFDocument24 pagesBSL 605 - Lecture 3 PDFShivati Singh KahlonNo ratings yet

- Undertakings in and Out of Court - Nadine, Barmaria PDFDocument30 pagesUndertakings in and Out of Court - Nadine, Barmaria PDFfelixmuyoveNo ratings yet

- LTD Reviewer From Jason LoyolaDocument21 pagesLTD Reviewer From Jason LoyolaDuncan McleodNo ratings yet

- Kawayan Hills vs. Court of AppealsDocument4 pagesKawayan Hills vs. Court of AppealsShaneena KumarNo ratings yet

- Young Drivers DeathsDocument49 pagesYoung Drivers Deathsjmac1987No ratings yet

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisFrom EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (49)

- The Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarFrom EverandThe Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)