Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Peter Drucker

Peter Drucker

Uploaded by

Milind Singh0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views23 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views23 pagesPeter Drucker

Peter Drucker

Uploaded by

Milind SinghCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 23

d

Br oO

yB8 2

Bao

sqcZza>

pero

aN mS

aes

eed 25%

ieee "2

wand 4 Malad

RAI

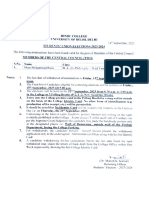

DEEP XEROX CENTER HINO FAI EGE R K.MLC COLLEGE MOBILE: 8130462424,9711492324

cee int s¥ematc wrk teat na

Preneurship in fc, par ofthe executive's jo

is a practical book, but its nota “how

th the what, when, and why.

ns; opportunities sid risks;

stefing,

compensation, and rewards,

ag Innovatiotrand entrepr

heading’: The Pract

” book, Inste

Such tangibles as polices

eneurship are discussed under three main

eof | Innovat

and Entrepreneurial Strategies, Each of these ig an

and entrepreneurship rather than a stage,

of Lnnovation presents innovation alike a

ine It shows fist where and how the entre-

vii

Structures and strategies,

Ep XEROX!

ssTATIONARY SHOP.

ee ing Available | 5

Alissedee tea

PRADE!

Ecological Niches

‘Changing Values and Characteristics

Conclusion: The Entrepreneurial Sociery

Suggested Readings

Index

About the Author

Boos by Peter F. Drucker

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

209

cep XERON!

RAD!

any sHOP

STAN

Hindu Coleg, jzable

324

712490

0462424

a+ ancopiLe: 8254

i

: PREPAC

hen they have been tested, vali:

than twenty years of my own con:

ns has been involved

fined, and revised in more t

tech” -ones suc

insurance companies; “world-class” banks, both Ameioey ad

European; one-man startup ventures; regional wholesalers of buildin

products; and Japanese multinationals. But a host of "non

also were included: several major labor unions; major comm

jons such as the Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. or CARE. t

international relief and development cooperat 2 few |

iversities and research labs; and rel

2 diversity of denominations

Becauge this book

tice, 1 was able to use act

both of the right and the wrong pc

name of an i

Is years of observation, study, and prac-

sases,” examples and illustrations

n itself has disclosed the story. Otherwise organizat

whom I have worked remain anonymous, as has been my prac-

in all my management books. But the cases themselves report

actual events and deal with actual enterprises.

Only in the last few years have writers on management begun to

{tention to innovation and entrepreneurship. I have. been

my management books for decades.

pay much

entirety and in systematic forty, This is surely'a fi

be accepted as a

topic rather than the last word—but I do hope it wi

seminal work. 1

Claremont, California

Christmas 1984

EEbOL ‘vErZOvOELE

zsL

~ corimon

: in the marketplace.

SUCRE he aa flanked by an Introduct

"> elates them to society.

0 a viable busi-

ive idea int

po’s and Dont’s of developing an innovative idea 4

o's and Dons : '

the institu-

fessor service. ship, focuses 0”

Entrepreneus reneurial

Par The Pate ot Ergon. dea vce

ae are iting BUSIRES: CO ee

service, t0 be @ 3

sa esp entepreneur? HOW nice and staff for entre”

successful entrepreneur?

What are the ih a discussion of in :

ns. =

k be |

takes? The section con:

their roles and

vidual entrepreneurs,

| Part Ill, Entrepreneurial Strategics» '2

innovation successfully to market. The test of an innovelcr»

not its novelty, its scientific content, or its cleverness.

‘by a Conclusion that

‘These three parts are fl

vation and entrepreneurship to the economy, and

Entrepreneurship is neither a science nor an art. [tis a practice. It

has a knowledge base, of course, which this book attempts to present

in organized fashion. But asin all practices, medicine, for instance, oF

engineering, knowledge in entrepreneurship is 2 means to an end.

Indeed, what constitutes knowledge in a practice is largely defined by

the ‘ends, that ice. Hence a book like this should be

backed by long years of practice.

‘My work on innovation and entrepreneurship began thirty years

ago; in tye mid-fifties. For two years, then, a small group met under

my leadership at the Graduate Business School of New York

every week for a long evening's seminar on Innovation

The group included people who were just

ir own new ventures, most of them successfully. It

book publishers; pharmaceuticals; a worldwide charitable or;

c y rganiza-

ton, the Catal, Aehaoees ‘of New York and the Presbyterian

‘The conceptssand ideas developed in this seminar wer

: Te test

its members week by week during those two years in their cana

Moasisil

S

Ie

$e é tc ESE ELE

b

Introduction:

The Entrepreneurial Economy

1 4

Since the mid-seventies, such slogans as

the “deindustrialization of America,” and a longrtenn “Kondeeret

‘S{2enation of the economy" have become popular and are invoked se

iCaxioms. Yet the facts and figures belie every one of these slogave

‘What is happening in the United States is something quite differeat «

Profound shift from a “managerial” to an “entrepreneurial” economy,

In the two decades 1965 to 1985, the number of Americans over

sixteen (thereby counted as being in the work force under the eon:

ventions of American statistics) grew by two-fifths, from 129 to 180

million, But the number of Americans in paid jobs grew in the same

period by one-half, from 71 to 106 million, The labor force growth

‘Was fastest in the second decade of that period, the decade from 1974

to 1984, when total jobs in the American economy grew by a full 24

million, : ‘

In no other peacetime period has the United States. created ais

many new jobs, whether measured in percentages or in absolute num.

bers. And yet the ten years that began with the “oil shock” in the late

fall of 1973 were years of extreme turbulence, of “energy crises,” of

the near-collapse of the “smokestack” industries, and of two siz Zable.

ns,

reste American development is unique. Nothing like it has happened

yet in any other country. Westem Europe during the period 1970 to

1984 actually lost jobs, 3 to 4 million of them. In 1970, westem Europe

still had 20 million more jobs than the United Statas; in 1984, it-had

almost 10 million less, Even Japan did far less well in job creation than

the United States. During the twelve years from 1970 through 1982, +

“the no-growth economy.”

‘bev29bOETS ‘ABO 3931109 I'W'YR-2937109 NONIH YILN3D XOUIX dIIGVud

veerevrtce'

spRpNRURIAL ECONOMY

fe ENTREE

| 3 67 grace

umber of schoolteachers has umes

mere 10 percent, that is, at less tha

topped in the as sch :

wake of thi ool enrol bs in Japan grew by @

Univers eae of the ear ste eve

declining. Ana in since then, employment thats! 1s performance in ereating jobs during the seved

early eighties, even hoy ‘ pan oane rice eso ran counter to what every expert Ie

Seen

Tmillion new jobs; we have created 40 million or mare

fet a permanent job shrinkage of

nal employing ins these ne

bai ae by small and medium-sized inst

reel acts peat uy on ee ea tere

ed in the United States every year now—abor aaa

t labor force a

go, The Jrowth, fo be unable to provide jobs

soa ‘o were going to reach work-

jes—the first large cohorts of

1949 and 1950. Actually,

hat number. For—some-

3 mid-eighties, every other married woman wi

seve

as were started in each ofthe boom years ofthe fifies and sation : “folds a paid job, whereas only one out of every five did so in 1970.

: ‘And the American economy found jobs for these, many cases

u ' far better jobs than women had ever held befo

‘And yet “everyone knows” th

‘were periods of “no growth,” of stagnat

y, “high tech” But things ae not thsi Amerie because everyone

me bs created since 1965 i the growth areas in the twenty-five years after World War

Faan ry, gh technology did not contibute more ts that came to an end around 1970.

High tech thus contributed no more than “smokestac In those earlier years, America’s economic dynamics centered in

additional jobs in the economy were generated elsewhere, And only one institutions that were already big and were geting bigger: the Forune |

or two out of every hundred new businesses—a total of ten thousand a county's largest businesses: governments, whether

year—are remotely “high-tech,” even in the loosest sense of the term. the large

i

i

a

everybody

the years

4)

We are indeed in the early stages of a major technélogical a

transformation, one that is far more sweeping than the most ecstat- . 5

” yet realize, greater even than Megatrends Al the np jobs provide in the American economy in the quarter

ire Shock. Three hundred years of technology came to an . century dfter World War Il. And in every recession during this period,

end after World War I Dyring those thee entries ‘the model for jo loss nd unemployment geared predominantly i small c

one: the event ions and, of course, mainly in small businesses.

Senn es Thue period bagen when But since the late 1960s, job creation and job grawth in the

star such as the sun. This.period began

* envisaged United States have shifted to a new sector. The old job creators

unknown French physicist, Denis Papit al Sites ave chia a a

a 'd 1680. They ended when we rej ave, actually last jobs in these last twenty years. Permanent =<

engine aroun : ide a star. For these jobs (not counting recession unemployment) in the Fortune $00 ¥

nuclear explosion the events inside a SF ft" - hhave been shrinking steadily year by'year since around 1970, at

advance in technology meant as it dees in irs, Since the first slowly, but since 1977 or 1978 at a pretty fast clip. 1

es--more speed, higher temperatures, higher pressures. Hines Tied" the pore 300 bad lost perme . a

end of World War Il, however, ‘the model of in jobs, And governments in Ame! yw employ fewer >

tioned in the test will be found inthe index than they did ten or fifteen years ago, if only-because the

«The dates ofall persons mentioned in i

£

x daIGvEd

‘vevesvOELs ‘AGOW 3931109 IW" 3937109 NANIH YILNaS XOUR

wzeteprtce

SSE St

: 7

T do not mean to imply that there are no economi

no economic:

gers. Quite the contrary. A major shift in the techn roblems or dan-

in

century surely presents tremendous problems cere

, and political. We are also in the throes of a majer political

great twentieth-century

ith the attendant danger of an uncontrl

or Mexico, su: i

sono takcot and disastrous rth oaks pote ee

global depression of 1930 proportions, And then there isthe Righter

ing specter of the runaway armaments race. But at least one of the

fears abroad these days, that of a Kondratieff stagnation, can be ae

sidered more a figment of the imagination than reality for the United

States. There we have a new, an entrepreneurial economy.

Itis still to early to say whether the entrepreneurial economy will

remain primarily an American phenomenon or whe

westem Europe,

Europe lags some ten to fifteen years behind America:

boom” and the “baby bust” came later in Europe than

States. Equal

westem Europe some ten years later than in the

Japan; and in Great Britain it has barely started y

hhics has been a factor in the emergence of the.entrepre-

ll

Where did all the new jobs come from? ‘The answer is from anywhere

source.

‘and nowhere; in other words, from no one single s ;

“The magazine Inc., published in Boston, has printed each yest SE

1982 list of the one hundred fastest-growing, publicly owned Amefican

companies more than five years and less than fifteen years 1°

+ has already happened that is ineomp:

syniRtAL ECONOMY

6 inTRODUICTION: THE ENTREPRM

i jobs to the Am

ice) are not expected to add as many j

ate 1980s and early 1990s as the id auton’

almast certain to lose.

‘But the Kondratieff theory fails tot

jobs which the American econo! ie

45 be sure has so far been following the Kondratiefl Sor Bae

United States, and perhaps not Japan either, SomnToe

ndratieff “long wave of

ey peed tat i sible with the theory of long-term

to account for the 40

y did create. Western

stagnation.

, Nor does it appear at al

the Kondratieff eycle, For

ale new jobs in the U.S. economy

has been in the last twenty years,

depend far less on job creation. The nur

‘American work force will be up to one-third smaller,for the

the century—and indeed through the year 2010—than it was in the

yeats when the children of the “baby boom” reached adulthood, that

js, 1965 until 1980 or so, Since the “baby bust” of 1960-61, the

an they were during the

‘baby boom” years. And with ipation of

‘women under fifty already equal to that of men, additions to the

‘number of women available for paid jobs will from now on be lim-

ited to natural growth, which means that they will also be down by

|, about 30 percent. :

For the future of the traditional “smokestack”" industries, the

Kondratieff theory must be accepted as a serious hypothesis, if not

indeed ag the most plausible of the available explanations. And as far

~ asthe indbility of new high-tech industries to offset the stagnation of

yesterday's growth industries is concerned, Kondratieff agai

deserves to be taken seriously. For all their tremendous qualitative

rtance as vision makers and pacesetters, quantitatively the high-

justries represent tomorrow rather than today, especially as

creators of jobs. They are the makers of the future rather than the

sly that we have simply postponed

the next twenty years the need to crc

jower than

1 eff can be considered di

proven: EA discret . The 40 millon new jobs created in the U.S.

economy during a “Kondratieff long-term stagnation” be

explained in Kondratieff's terms. Pee tamnat be

ray

ny

= eg

|=

and by a finan

Ad eY 2 finance company that leases mai

x Wee .

the most eee eeusinesses 1 know personally, the one that has crested

during the fi 4 and has also grove the

two thousand new oor mente

Shimslone has cre ind new jobs, most of them

Exchange, only about one-eighth ofla ere Nee oes

ks, The res

professional,

suburbs, who

places «

and thus looks for

ic enough not to

mation about the growth sectors

hundred fastest-growing "mid-size" companies that commas

with revenues of ion and $1 billion. This study was-

conducted during 1981-83 for the American Business Conference by

two senior partners of McKinsey & Company, the consulting firm:*

These mid-sized growth companies grew at three times the rate of

the Fortune 500

ing jobs steadily since 1970. But

added jobs between 1970 and 1983

in the enti

jobs in U.S, industry d

es the rate of job growth

mid-sized growth companies increased their employment by one full

ercentage point. The companies span the economic spectrum. There are

igh-tech ones among them, to be sure. But there are also financial serv-

Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, for instance. One of the best performers

is a company making and selling living-room furi

a third, high-quality

the grouy

household paints; @

i

another one is making and marketing doughnut

chinaware; a fourth, writing instruments; a fifth,

was published under the ee eal

Companies," by Richard E. Cavenaug!

1983 issue of the MeKinsey Quarterly.

jh and Donald K. Clifford,

sales and in profits. The Fortune 500 have been los-

CH

ET

U.S. economy. Even in the depression years 1981-82 |

ices companies—the New York investment and brokerage firm of

cessons from America's Mid-sized Growth |

TIONARY SHOP

1@, Delhi

7042223162

ling Available

AllReaaing 3

10462424,

PRADEEP XEROXisTa

Hindu Cot)

813%

ANGE

4

URN

INARY SHOP

98, (MM) 813046340,

Ex

‘OX/STATION

NOE

- PRADEE®

Hindu ER

8 IVTRODUCTION: THE ENTREPRENEURIAL ECONOMY

Being confined to publicly owned companies, the list is heavily

biased toward high tech, which has easy access to underwriters, to

stock market money, and to being traded on one of the stock

exchanges of over the counter. High tech is fashionable. Other new

ventures, as a rule, can go public only after long years of seasoning,

and of showing profits for a good deal more than five years. Yet only

‘one-quarter of the “Inc. 100” are high-tech; three-quarters remain

most decidedly “low-tech,” year after year.

In 1982, for instance, there were five restaurant chains, wo

and twenty health-care providers on

the list, but only twenty to thirty high-tech companies. And whilst

‘America's newspapers.in 1982 ran one article after the other bemoan-

ing the “deindustrialization of America,” a full half of the Inc. firms

were manufacturing companies; only one-third were in services,

Although word had it in 1982 that the Frost Belt was dying,

Sun Belt the only possible growth area, only one-third of the

100" that year were in the Sun Belt. New York had as many of these

fast-growing, young, publicly owned companies as California or

‘Texas. And Pennsylvania, New Jetsey, and Massachusetts—while

supposedly dying, if not already dead—also had as many 2s

and as many as New York. Snowy, Minnesota,

ists for 1983 and 1984 showed a very similar dis-

oth to industry and to geography.

‘women’s wear manufacturers,

aye

a Califomia manufacturer of physical exercise equipment for the

home,

ts yields the same pattern.

«nent. The portfolio of one of the most successful venture cay

investors does include several high-tech companies: a ew com-

cchnology, and

s portfolio, the new

revenues and

|-83, is that most mundane

barbershops. And

, both in sales growth and profitability, comes a chain of

try offices, followed by a manufacturer of handtools

next to

denti

PRADEEP XEROX/STATI

IONARY Sup

'D

98,

Hindu Cotto

NEC COLLEGE MOBILE: 8130462424,9711491324

fel

all

saa

All Res

NEERIAUNEY,

PRADEEP XEROX CEI

‘DebZSPOETR # WH 8

O€T8 :3TIGOW 3937109 9'W'H B 3937109 NaNIH Y3INID XOUBY azzQVvala

vzetevttce'

EE

ly lover costs, The

he He Ba

ine

224 Wiliam lenny Dyas eat

ership of public services. Pioneering. wok in

=xas—in San Antonio and in Houston,

in Minneapls the Huber Huey

psa ny of Mine, Cone ats Carey

eas in Minneapolis bulang pub

ips in education and even in the management re.

|s there anything

‘other than grow

‘Since Joseph Schumpeter first pointed

that what aetually happened inthe United States and in Germany inthe

fifty years between 1873 and

Bee The frst Kondratieff cy!

ith the crash ofthe Vienna

an end wit

depres :

trial stagnal

indus allen) 0

weno THE ENTREPRENEURIAL FOND!

snd publishing local newspapers

re eventh produces yam forthe textile

knows" that growth in the

eer ethan al of hese

sixth ha expanded from pi

censumer marketing Services;

ny,

‘amecian ‘economy is ‘exclusively ee

“a a the growth sector ‘of the U.S.

fusing sti

Tomake things move ry vo fiezn years, while erly tone

1g number of enter-

ough quite afew

je

in deep trouble these days. But there

chains, both “profit” and

faster growing are the

25 for the terminally il,

ratories, freestanding surgery centers,

ic “walk-in” clnies, or c2-

ters for geriatric diagnosis and treatment.

“The public schools are shrinking in almost every American com.

decline in the total number of children of

f the 1960s, a whole new

In the small

y afew mothers for their own children,

1 school with two hundred students going

tristan” school founded a few

taking over from the city of

fifteen years ago and left

3¢ last five years. Continuing

he form of executive manage

career managers or refresher courses for

I therapists, is booming;

ring the severe 1982-83 recession, such programs suffered

onlya short setback.

‘One additonal area of entrepreneurship, and a very important one,

ig the emerging “Fourth Sector” of pub fe partnerships in which

sof muna, deters perform

e ‘money. But then they contract out 2

sence proton, gibagecllection, orbs taspertation 0

«private business on the bass of competitive bids, thus ensuring both

rs ago by the local Ba

high school by

the stagnation in

the old industrigs, such as railway construction, coal mining, or textiles

But this did not happen in the United States or in Germany, of

indeed in Austria despite the traumatic impact of the Viennese stock

market crash ftom which Austrian never quite recovered.

‘These countries were severely jolted at fist. Five years later they had

polled out of the slump and were growing again, fast. In terms of

“echnology”” these countries were no different from stagnating

Britain or France. What explains their different economic behavior

‘was one factor, and one factor only: the entrepreneur. In Germany, for

instance, the single most important ecanomic event in the years

between 1870 and 1914 was surely the creation ofthe Universal Bank.

Deutsche Bank, wis founded by Georg Siemens

specific mission of finding entrepre

and forcing upon them organized, dis

EXCHANGE

RETURN

0462424

STATIONARY SHOP

(M) 8131

v

seems to be happening in the

5 and pethaps also to some extent

igh tech isthe one sector that isnot p

PRADEEP XEROX/S'

Hindu College,

NO

Xe major modem economists only Joseph Sch .

yp Seed himself with the entepreneurandisipea

Every economist knows that important and his

impact. But, for economists, ent ip isa“meta-economic” © & oy

\ event, something that profoundly influences and indeed shapes the a°.o p the world will beat a path to your door” It does not yet

Br cconomy without itself being part oft. And so too, for economists, is“. - 3 = Bf oecurto them to ask what makes a mouseuap “beter” ot for who?

technology. Economists do not, in other words, have any explanation Span ‘There-are, of course, plenty of exceptions, high-tech companies

as to why entrepreneurship emerged as it did in the late nineteenth’ soR Q that know well how to manage entrepreneurship and inno

century and as it seems to be doing again today, nor wh Bee 8 en there were exceptions during the nineteenth century,

B _toone country or to one culture. Indee : 8 Siemens, who founded and

entrepreneurship becomes effective are probably

The causes are likely to

name. There was George Westinghot

inventor but

em

0422

PRADEEP x

snr

AIL

iaoadp.

7

ig, surely,

ly age numbers of

in the last twent f

nyone looking atthe young Amaia ft ie 96

Mee iced: How do we enplai, fr instance, a 16S

=< therevare such large numbers of Ped

PRADEEP XEROX CENTER HINDU COLLEGE &K.M.C COLLEGE MOBILE: 8130462424,9711491324

‘vebz9vOETS TGOW.393T109 JW" B. 3937109 NANIH WILNID XOURX JIIGVUE

beerevttce'

es

1s

1930s, there were a few major enterprises

ly businesses—that pr

DuPont Company an

hat time most-

United St

agement boom+The social technology we call management was first pre

sented tothe general publi including managers themselves, some forty,

ago. It then rapidly became a discipline rather than the hitor-miss prachee of

a few isolated true believers. And in these forty years management has had as

"much impact as ay ofthe “scientfe brealchroughs" ofthe petiod-—pertaps

1 good deal more. It may not be solely or even primarily responsible for the

fact that society in every single developed country has become since World

le for the fat that in every developed society today the ior

ity of people—and the overwhelming mao ofeduatel fet

‘employees in organizations, including of course the bosses themselves, who

increasingly tend to be “professional managers,” that is, hired hands, rather

than owners, But surely if management had not emerged as a systematic dis-

cipline, we could not have organized what is now a socal reality in

developed country: of organizations and the “employee

We still have quite a bit to learn about management, admittedly,

and above all about the management of the knowledge worker. But

the fundamentals are reasonably well known by now. Indeed, what

‘was an esot

in large companies did not in fact realize that they practiced manage-

ment, now has become commonplac . 5

But by and large management until recently was seen! as being

Chinese government after the

Enterprise Ntanagement Agen

import a Graduate Business School from the United Stats.

'

* mons for long years and to ch

* todevelop as a

FroNoMY

4 INTRODUCTION: THE ENTREPRENEURIAL EOF

fave risks rather than big

oe Eis the status seekers, the “me-too-

n security? Where are the hedonists,

the conformists? Conversely, where are

‘we were told fifteen years ago, were turning

uues,on money, goods, and worldly succes:

America a “laid-back” if not pastor

3 fit in with what f

explanation, it dobs no th wa

thirty years—David Riesman in y

in Pr epichan ‘Man, Charles Reich in The Greening of America,

cr Herbert Marcuse—predieted about the younger generation. Surely

the emergence ofthe entrepreneurial economy is as much a cultural an

psychological as itis an economic or technological event. Yet whatever

‘are above all economic ones.

attitudes, values, and

above all in behavi called management.

‘What has made possible the emergence of the entrepreneurial econo-

my in America i8 new applications of management:

to new enterprises, whether businesses or not, whereas most

* people until now have considered management applicable to

existing enterprises only;

to small enterprises, whereas most people were absolutely sure

ly a few years ago that management was for the “big boys”

jealth care, education, and so on), whereas

“business” when they encounter the

:: to the search for and

for satisfying human

Asa“usefil knowledge;

the other major areas of kno

techné management is the same age as

cdge that underlie today’s high-tech

te physics, ger or

time around World War I.

atuse-

had

« before it could become a discipline. By the late

the

DAR Plea hint Na a it \

mn

i

>

of the succes:

years—management was being apy

hit-and- }, Mom-and-;

as qu:

ibsolute cleanliness

f these, trai

s, and friendliness,

ined for them, and geared comp:

rensation to ther

Management is the new technology (rather than any specific new

seience’or invention) that is makin,

entrepreneurial economy. It is also about to make America into an

entrepreneurial society. Indeed, there may be greater scope in the

United States—and in developed societies generally—

innovation in education, health care, government, and pol

ss and the economy. And again, entrepr

ty—and it is badly needed—requires above all application of the

basic concepts, the basic fechné, of management to new problems and

new opportunities.

i i in general

novation what we first did for management i

years ago: to develop the principles, the practice, and the dis

management, and fairly advanced management-at”

ig the American economy into an *

‘This meansithat the time has now come to do for entrepreneurship

16 INTRODUCTION: THE ENTREPRENEURIAL ECONOMY

confined to business, and within business, to “big busi

carly seventies, when the American Management Assoc

the heads of small business residents’ Course” in Manager

it was told again and again: “Management? That's not for

only for big companies” Up to 1970 of 1975,

admi

me—t

, American hospital

ejected anything that was labee

are still saying the same thing even

simultaneously complain how “badly managed” their

id indeed for a long time, from the end of World War If unt

rogress” meant building bigger institutions.

‘This twenty-five-year trend toward building bigger organizations

in every social sphere—business, labor union, hospital, school, uni-

ity, and so on—had many causes. But the belief that we knew how

to manage bigness and did nof-really know how to mariage small

enterprises was gurely a major factor. tt had, for instance, a great deal

todo withthe lsh tovard ihe very large cowsfined Amesean hgh

school was argued, “requires professional administra

‘tion, and this in tum works only in large rather than small enterprises.”

During the last ten or fifteen years we have reversed this trend. In

for anyone seriously sick. “The

hospital, the better care we can take of

ge in

‘acquired the competence and the confidence t0

stat masinesse," that, healcate

tena 2 eeveeere nacinit es 8190862424,9711493324

veetebTtLe'bzpzap0ETs -TEOW. 3937109 9'W'W/8. 3937109 NGNIH Y3LN39 XOURK dIzVud

THE PRACTICE

OF INNOVATION

|

Innovation is the specific tool of entrepreneurs, the means by which

they exploit change as an opportunity for a different business or a

ferent service. It is capable of being presented as a discipline, cap

ble of being learned, capable of being practiced. Entrepreneurs need

to search purposefully for the sources of innovation, the changes and

their symptoms that indicate opportunities for successful innovation.

And they need to know and to apply the principles of successful

vation, ‘

Bee Es

L

1

Systematic Entrepreneurship

1 |

“The id the French economist J.

‘shifts economic resources o1

higher product

“The entrepreneur,” sai

nd “entrepreneurs

S, for instance, the entrepreneur is often defined

as one who starts his own, new and small business. Indeed, the cout:

cs in “Entrepreneurship” that have become popular ‘of late in

American business schools are the linear descendants of the coutse in

starting one’s own small business that was offered thirty years ego,

But not every new small business is entrepreneurial or represents

entrepreneurship,

The husband and wife who open another delicatessen stofe-o

another Mexican restaurant in the American suburb surely take a risk.

But are they entrepreneurs? All they do is what has been done rhany

times before, They gamble on the increasing popularity of eating out

in their area, but create neither a new satisfaction nor new consumer.

demand. Seen unde

irs is a new venture.

however, was entrepreneurshi

concepts and managem

customer?), standardizing t

and by basing training on the analysis

is

8

ie

q

:

is perspective they are surely not entrepreneurs *

did not invent

‘bevCSpOELE ‘3TIGOW. 3937109 9'W'H® 2937109 naNIH UBLNED XOWRX d330viid

beetevrrce'

mneing arm,

Upheaval

is now spreadin

ll. G.E. Credi in

'd Marks and Spencer have many things i

large and established businesses that are to

What makes them “entrepreneurial” are sp

than size or growth,

rie eentfepreneurship is by no means confined soleiy to eco-

Ne Calter text for a History of Entrepreneurship could'be found

ment of the modern univers

‘an university. The modem

invention of a German diplomat and civil ser

. Wilhelm von Humboldt, who in 1809 conceived and founded the

University of Berlin with two clear object tak

fic leadership away from the French and

the energies released by the French Re

ly Napoleon. Sixty years

ity itself had peaked,

treat ferrous

2 thi

ted a new market and a new cus-

isthe growing foundry started by a hus-

2 ago in America's Midwest, fo

ly entrepreneuri

band and wife team a few years ago

land and

itches for a natural gas pipeline across Alaska. The science

needed is well known; indeed, the company does little that has not

been done before. But in the first place the founders systematized

mn: ‘they can now punch the performance

ir computer and get an immediate printout of

rent required. Secondly, the founders systematized the

dozen pieces o:

ings are being

‘effect, a flow process rather than in batches,

computer-controlled machines and ovens adjusting them:

selves,

‘castings of this kind used to have a rejection rate of 30 to

40 percent; iew foundry, 90 percent or more are flawless when

line. And the costs are less than two-thirds of those of

cheapest competitor (a Korean shipyard), even though the

/estem foundry pays full American union Wi

‘What is “entrepreneurial” in this business is not that

small (though growing rapi

ind are distinct and separa

to create “market niche”

to have special char-

indeed, entrepreneurs

ite something new,

Indeed, entrepreneurshi

8 Tong Mstory of starting new entrepreneurial businesses frase eos

qo.

pee EE EH EEE

soon

leadership in scholarship and

had gamed worldwide lead-

iin

te of Technology ih the New

in Boston Sanja Clara and Golden Gate

$0 on, They have constituted a major

in American higher education in the last

9 these new schools seem to differ

ions in their curriculum. But they were

esigned for a new and different “market"—for people

ther than for youngsters fresh out of high school, for

tudents commuting tothe university at ail hours

er than for students living on campus and

time, five days a week from nine to five; ikl

Widely diversified, indeed, heterogenous back

founds rather than for the

5,” and to a major shift

They represent entrepreneurship,

One could equally write a casebook én ent

Cn the history ofthe hospital, from the fi

though of course they need ra hospital in the late eighteenth eentu

noneconomic) creation ofthe various forms of

take risks, of course, but so” *

of economic a

is the com

ip based

ist appearance of the mod-

yin Edinburgh and

the “community hos

They are not investors, either T

does anyone engaged’ in

essence of economic act

Fesources to future expectations, and that means to

ri

Menninger

5 health-care cen

iny and

entrepreneur is also not an employer, but ean be and

an employce—or someone who works alone and entirely

by himself or herself,

tory surgi

ri enters where

on caring for

ion is eneprene

the characteristics,

ig marks ofthe service institution * What

' co Oy

spon rates, but ao Chapter 14 ofthis Book

Monagersent Tasks, Responsibilities, Prates, ap

"Ont seth ston Peomance inthe Seni lt

Eirepreneurship inthe Service Institution.

0 (Chspers

Rucaitahles

5

=

‘vebe9POET8 :311G0W. 3937109 'W'¥9 3931709 NONIH ULNID XOUIX dIa0vid

beetevites'

Systematic &

27

ion of technology—he was

Of technology—he

entrepreneurship into either hi

nomic change in Marx beyond

that is, the establishm rut

Property and power relationships, and he!

i outside the economic system itself.

say Seph Schumpeter was the first major econom

fay. In his classic Die Theorie der Wirtschafilichen bu

Dynar

ne of the best his-

1 entrepreneur and

is economics. All eco

n of present resources,

e f ck

to go back to

icklung (The

Schumpeter

than John

tet. He postulated that

, normally considered “eco-

inly economic criteria are hardly appropriate to deter-

f education (though no one knows what other criteria,

sumption and

resources, whet

cc between entrepreneurship whatever the sphere.

‘The entrepreneur in education and the entrepreneur in health care—both

have been fertile fields—do very much the same things, use very much

‘and encounter very much the same problems as the

entrepreneur in a business or a labor union,

Entrepreneurs see change as the norm and as he

do not bring about the change themselves. But—and

26 “rin PRACTICE OF INNOVATION

, people who need certain-

wellin eneprenerial challenges. Tobe sur, people who need

ty, unlikely to make good entrepren. But such people are ut

1y't0 do. well in 2 host of other acti

Hance orn command postions ina

ofan ocean ern al uch pursuits decisions have

ence of any decision is uncerainy:

ee Srcnane who can face up to decision making can learn to be

an eneeproveur and to behave entrepreneurially, Entepreneurshi,

them is behavior rather than pers is foundation les

“imeOncept and theory rather than

1

Every practice rests on theory, even if the practitioners themselves

are unaware of it. Entrepreneurship rests on a theory of economy and

ety. The theory sees change as normal and indeed as healthy

ees the major task in society—and esp:

‘my—as doing something different rather than

already being done. This is basically what Say, two hundred years

ago, meant when he coined the term entrepreneur. It was intended as

‘a manifesto and ‘as a declaration of dissent: the entrepreneur upsets

and disorganizes. As Joseph Schumpeter formulated it, his task is

“creative destruclion.”

Say was an admirer of Adam Smith. He translated Smith's Wealth

ution 0 e60-

f the entrepreneur and of entreprene

ical ics and indeed incompatible

iready exists, as does

uding the Key

io

and weather, gov-

pestilence and war, but also technology. The tra-

ditional economist, regardless of school or ddesnot deny, of

course, that these extemal forces exist or that they matter. But they

| aTe not part of his world, not accounted for in his model, his equa-

tions, or his predictions. And while Karl Marx had the keenest appre~

29

one hundred new businesses on

® PRACTICE OF INNOVATION

ful our out of rae Tei

of

ple ofthe entreprene yo ies

sk Surely there are ny or WhO some

Chana ad entepreneurship—the enrepreneur always searches for

00 many of , change, responds to it, and expo

neursip tbe a fuke a 9 dispensation ef low-risk entrepre:

mere chanee. ‘Bods, an accident, oy

‘There are also enough individual ent acu om

ting average in stating new Ventures isso hiens a0UNd Whos bat : 7

of the high tisk of entre oa Entrepreneurs ‘commonly believed, is enormously risky. And,

Entrepreneurship i mais oe deed, n such highly vise areas of inmovation as igh ok enn

manatees Gara, ly because so few of the ts fr instance, or bogenetcs—tbe casualty rate i high sed

ives ig. The ‘he chances of successor even of survival seem i 6

‘They violate elementary and well-known ra s, Th Hn : But why should this be so? Entepreneurs, by deinen, shift

Chane stteh entrepreneurs, To be sure of low produetivty and yield to areas of higher

Chapter 9), tech entrepreneurship and innovation ate i iy and yield. OF course there is a risk they may -

'y more difficult and more risky than innovate based on econo! : if they are even moderately successful, the retusas shold

and market structure, on OF even on somethin adequ tever risk there might be. One

seemingly nebulous and intangible as Weltanschawungperceptions epreneurshi to be considerably less risky then

and moods. But even highstech entrepreneurship need nate opt Indeed, nothing could be as risky as optimizing

Bell Lab and IBM prove Itdocs nord bee {floes in areas where the proper and profitable course & imonee

needs to be managed. Above al fee citotan besyici? uh Non, that is, where the opportunities for innovation already exist.

pinposefl nmosang 0 be based on Pret atreprenersip should eth least risky rather than

“i fac, there are a

‘ ion

States, for instance, there i Beli Lab the innovative

am of te Bell Telephone System. For more than seventy yo

: from the design ofthe first automatic switchboard argued

i the dengn ofthe optical fiber cable around 1980, luting

Sy conductor, but also basic theoretical and

So Lab produced one

Boh

BES

ean

Bees

: 2824,971 91324,

PRADEEP XEROX CENTER HINDU COLLEGE & K.M.C COLLEGE MOBILE: 8130462424,

° EROK!

PRA oe Cote

Ail Roe!

6130462424,

Seven Sources un

Equal ever ch

tever changes

already existing resources constitutes innovation

jere was not much new technology involved in t

3K body off is wheels and onto a eatgo vessel

he cor id not grow out of ted

atl th et, did not grow out of technology at

rather than which meant that whi

a ‘ch meant that what re.

make the time in por as shor as posible, But this wumdsum ime,

tion roughly quadrupled the productivity of the ocean-going

and probably saved shipping. Without it, the tremendous expat

World trade in the last forty years—the fastest growth in any major

conomic activity ever recorded—could not possibly have taken

ing a

ig device

place. ‘

What really made universal schooling possible—more so than the

P tment to the value of education, the systemat

ing of teachers in schools of education, or pedagogic theory—was

that lowly innovation, the textbook. (The textbook was probably the

invention of the great Czech educational reformer Johann Amos

Comenius, who designed.aud used the first Latin primers

popular com

'y poor teacher can get a

ity-five studel

Innovation, as these example:

cal, does not indeed have to be

innovations can compete in terms of

vations as the newspaper or insurance. Installment puying

transforms economies. Whereyer introduced, it changes the econo-

ven, regardless almost of the

my from supply-driven to demaiid:

fe level of the ecpnomy (wliich explains why installment

the rrxist government com

the Communists di

1959). The hospi

shtenment of

ci

Nances in medicine. Management, that is, the “useful knowlege

aevaiables man for the first time to render produetive people of

Is and knowledge working together in an “organiza

‘as converted modern soci

f this century. It hi

something, by the way, for

tion,” is an innovation of

ety into something brand new,

not a resource. Bacteriologists went

cia aa a il

2

=—

1 Sources

Purposeful Innovation and the Seven

for Innovative Opportunity

‘

i fic instrument of

" Entéeprenes Innovation is the speci of

Barner ns, METS pga esures WS ACL

Sepasiy to rele ee, creates & THROU:

lc anh 8 ee ae, Un Se

thing in nature and thus endows it them,

st another rock. N

fuer f the ground

every plant is a weed and every ag

ther mineral il seeping out Of he ror

more than a century ago, neithe

nor bauxite, the ore of aluminum, =

ances; both render the soil infertile.

cultures against contaminat

bacteri i

London doctor, Alexander Flemin

“exactly the bacterial killer bacteriol

the penicillin mold became a valuable resource.

‘Fhe gume hotds just as true in the social and economic spheres

‘an economy than “purchasing

. power” But purchasing power is the creation of the innovating

entrepreneur. :

"The Americans farmer had virtually no purchasing power in the

early nineteenth century; he therefore could not buy farm machinery.

There were dozens of harvesting machines on the market, but how-

ever miuch he might have wanted them, the farmer could not pay for

them. Then one of the many harve e inventors, Cyrus

McCormick, ent buying. This enabled the farmer to

pay for a harve out of his future earnings rather than out

of past savings—and suddenly the farmer had “purchasing power” to

buy farm equipment.

: 30

FS ago to concentra

fined entrepreneurshi

8 a modem economist woul

ind terms rather than

and satisfaction obtaine

shift from the integrated steel mi

with steel scra

-mi

ip rather than iron ore and ends

» beams and rods, rather than raw steel

best described and analyzed in sup-

ind the customers are:

lower, And the same

then has to be fal

ply terms. The end product

more so, are better described or analyzed in terms of consumer

32 ‘Tit PRACTICE OF INNOVATION

which we have neither political nor Social theory: a society of

rBjooks on economic history mention August Borsig as the first *

‘man to build steam locomotives in Germany. But surely far more

Important was his innovation—sgainst stenuous opposition from

‘raft guilds, teachers, and government bureaucrats—of what to

day is the German system of factory organization and the foundation

of Germany’s industrial strength. It was Borsig who devised the idea

of the Meister (Master), the highly skilleg and highly respected sen-

ior worker who runs the shop with considerable autonomy: and the

Lehrling System (apprenticeship system), which combines pra

1g (Lehre) on the job with schooling (Ausbildung) in the

room. And the twi entions of modern government by

in The Prince (1513) and ofthe modern

lower, Jean Bodin, sixty years later, ha

impacts than most technologies.

One ofthe most interesting examples of soc

importance ean be seen in modem Japan,

From the time she opened her doors to the modem world in

1867, Japan has been consistently underrated by we

despite her successful defeats of China and ti en Rus in 1894

and 1905, respectively; despite Pearl Harbor; and despite her sud.

den emergence as an econot superpower and the toughest com-

petitor in the world market of the 1970s and 1980s. A major rea.

Son, Perhaps the major one, is the prevailing belief that innovation

has to do igs and is based on science or technology. And

the Japatiese, so the common belief has held

in the Wes

surely had more lasting

‘Was to avoid the fates afi

century China, both of which were conquered:

ternized” by the West The basic ai

to use the weapons of the ‘West to hold the

innovation was far more crit

‘aph. And social innova

ons as schools and

ph 0h ope, Hai

All Reading Av

ica aera

‘’eb29b0E18 :31IGOW. 3937109 'W'¥:R 3937109 NONIH WIINID xOUaX d33qvud

beetevrice'

re

JF INNOVATION '

and different, Syst

Poseful and org

analysis of the ope

or social innovai

therefore consists in the pur-

nges, and in the systematic

'eS such changes might offer for economic.

Sure, there are innovations that in themselves consi jor

fone ofthe major tecnica imvaton, such asthe Wigh ene oe

plane, are examples. But these are exceptions, and fairly uncommon oxee

aa innovations are far more prosaic; they exploit change, And

us the discipline of innovation (and itis the know! repre

neurship) is a diagnostic : mica

change that typically offer entrepreneurial opportunities, ¢

Specifically, systematic innovation means monitoring seven

sources fot innovative opportunity,

four sources lie

‘They are therefore

service sector. Th

able indicators

to happen with

hanges that have already happened or can be made

le effort: These four source areas are: :

+ The unexpected—the unexpected success, the unexpected fail

is assumed to be or as it “ought to be’

jovation based on process need;

ianges in industry structure or market structure that catch

everyone unawares. z

1 i

The second set of sources for innovative. opportu

three, involves changes ouiside the enterprise or indust

+ Demographics (popul

+ Changes

+ New knowledge, bot

The lines between these seven source areas of innovative opportuni

ties are blurred, and there is considerable overlap between them. They

can be likened to seven windows, each on a different side of;the same

. ocial innov:

values and consume!

sp enactice OF

hs

atisfactions, a8 aTe SUCK 97

developed by Henry 1

's, or the money-™mar!

¢ of Ti

fund of the late

az

“inven-

rary waste “iver

Se eeu atl

tention was myeeius

hi

the time World War I broke

oseful

me “research,” a systematic, purposeful

ers fanned and organized w figs predict bo

: at and likely to be achieves :

Eneepencur will have to leam to practice sstematc innovation.

Secesfleaepreneus donot wait unt “the Muse kisses them”

wolutionize the

ake one rich

dt create a

overnight” Those entreprencurs who start out with the idea that

ake it big—and in a hurry—can be guaranteed failure. They

imost bound to do the wrong things. An innovation that looks

‘cal virtuosity; and inno-

a McDonald's, for

vations

instance, may turn into

same’ applies to nonbusiness, public-service inno

‘Successful entrepreneurs, whatever the | motivation—

be it money, power, curiosity, or the desire for fame and recogni-

n—try to create value and to make a contribution. Still, successful

iply to improve on

‘or to modify it. They try to create new and dif-

and new and different satisfactions, to convert a “mate.

Tesources in a new and

S.

ive configuration,

change that always provides the opportunity for the new

11

— =

Principles of Innovation

4 1 |

cians have seen “mis

ina inesses recover suddenly “soi

neously, sometimes by going to faith healers, by ¢

absurd by sleeping during the 1

y g to some

day and being up and about all

extremely rare;

I cases do die, after all

innovations that are not

stematic inanner. There are

ee 4 ‘and whose innovations are .

ier than of hard, orgar 1, pur-

poseful work. But such innovations cannot be replated They exroot

be taught and they cannot be learned, There is no known way to teach

someone how to be a genius. But also, contrary to popular bel

z the romance of invention and innovation, “flashes of ge

a

i

—.

“flash of geni

uncommonly rare. What is worse, I know of not one such

genius” that turned into an innovation. They all remained bi

ideas.

recorded history was surély

idea—submarine or helicop-

ter or automatic forge—on every single page of his notebooks. But n

one of these could have been converted into an innovation with the tech-

nology and the materials of 1500. Indeed, for none of them would there

133

2 “IME PRACTICE OF INNGVATION

exploit, And in these areas we know how to look, what to look fos,

do.

All one can do for

jovators who go in for bright ideas isto tell

them what fo do should theit-innavation, against all odds, be suc-

Tul ‘Then the rules for a new venture apply (see Chapter 15). And

1 reason why so much of the literature on entre-

Starting and running the new venture rather

than with innovation itself.

‘And yet an entrepreneurial economy epnnot dismiss cavalierly

innovation based on a bright idea. The individual innovation

kind is not predictable, cannot be organized, cannot be systematized,

and fai 1c overwhelming majority of cases. Also many,

many, are tri

cations for new can openers, for new wi

an for anything else. And in any list of new patents there

farmer than can: double as a dish towel. Yet

the voluime of such bright-idea innovation is 50

centage of successes represents 2 substantial source of new

es, new jobs, and new performancé capacity for the economy.

In the theory and practice of innovation and entrepreneurs

bright-idea innovation belongs in the appendix. Bu

ty can do, per-

‘hat one does,

iscourage, penali

discoura vidual who tries to come up with a brig

innovation (by raising patent fees, for instance) and generally

courage patents as " short-sighted and deleterious.

nannies O8amAcdana 711401774

XOWIX d3zqvud

‘3IgOW. apy ;

37109 9'W8. 3937109 nant Ua:

B]

URTGVITLE' bebzapoete

SSPE ae CE EEC

Prncoes of tmovation Bs

a

ies, Denogis, fr gz

ro. I

ices mama srem nite |

: Where 8

Pose Sonam ena ne eB car enguty

0 exanee 10 someone innovating anew socel ane,

: cre i ‘1 a

Sources of innova eat Changing demogrpis Bat i 8

Systmatenly gues aren shld ese edind 8

Sto be organized, and i

8

®

8

the customers,

their needs are,

Receptivity can be

this or that approach will net frig ae

of the people who have to use

people who have to use it

a int their opporténity?” Otherwise one

ing the right innovation in the wrong f

happened tote leading producer of computer programs fer learing

a se excellent and effective

not used by teachers scared stiff of the computer, who pereived the

machine as something that, far from being helpful, threatened them.

3. An innovation, to be effective, has to be simple and it has to be

shor

focuse’

takingly simpl

is for people to s.

Even the innovation that creates new uses and new markets should be

c, clear, designed application. Itshould be focused

sfies, on a specific end result that it produces."

taht small. They are not grandiose: They try

be to enable 2 moving vehicle to draw

the innovation that made possi-

to do one specific

electric power while it runs along rals—t

INLSIMOWAX daROVEd

dOHS At

se PRACTICE, OF INNOVATION

f the time. Every

ve society and economy 0

in the so inventor” of the steam engine,

know that Thomas

performed

134

ceptivity

have ben any ee the

1. Historians of technology

he frst steam engine which actual

imped set of an English coal mine. Both men

Watt's steam engi

innovators.

wation in which newly available

‘and the design of 2“

ized, systemat

isthe very model of 28 es

rn

i ae ire

nich had been created by ‘Newcomen’s engine

the true “inventor” of the com-

‘modem technology, was nei~

it Anglo-Irish chemist Robert

Only Boyle’s engine did not

jon of gun~

particular is

knowledge

ther 3Watt nor Newcomen. It was the

who did so in a “flash of genius.

Boyle,

werk and could not have worked. For Boyle used the expl

and this so fouled the cylinder that it had to be

jea enabled first Denis

power to drive the piston,

after each stroke. Boyle’s id

the gunpowder engine),

taken apart and cleaned i

Papin (Who had been Boyle's assistant in building

hen Newcomen, and finally Watt, to develop a working combustion

jus, had was ab in the his-

ion.

f°

fal innovation resulting from analysis, system, and

3 discussed and presented as the practice of

innovation, But ths is all that need be presented since it surely cov-

crs at least 90 percent of all effective innovations. And the extra

nary performer in innovation, as in every other area, will be effective

only if grounded in the discipline and master of it

‘Whatthen, ae the principles of innovation, representing the hard

core‘of the discipline? There are a number of “do’s”—things that

have.to be done. There are also a few “dont

+ ternot be done, And then there are what I would cal

“The purpose

hard work isa that can b

. THE DO'S

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Hindu College Parliament - ConstitutionDocument4 pagesHindu College Parliament - ConstitutionMilind SinghNo ratings yet

- PM NominationDocument2 pagesPM NominationMilind SinghNo ratings yet

- Hindu College Students' Union Elections 2023-2024: Following Members Central CouncilDocument1 pageHindu College Students' Union Elections 2023-2024: Following Members Central CouncilMilind SinghNo ratings yet

- Public-Private Dichotomy, Mohit BhattacharyaDocument5 pagesPublic-Private Dichotomy, Mohit BhattacharyaMilind SinghNo ratings yet

- Electoral Systems AssignmentDocument25 pagesElectoral Systems AssignmentMilind SinghNo ratings yet