Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stadler (1994)

Stadler (1994)

Uploaded by

Luis Antonio La Torre Quintero0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views35 pagesOriginal Title

Stadler(1994)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views35 pagesStadler (1994)

Stadler (1994)

Uploaded by

Luis Antonio La Torre QuinteroCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 35

Real Business Cycles

George W. Stadler

Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Dec., 1994), 1750-1783.

Stable URL:

btp//links jstor.org/sici?sict=0022-05 15% 281994 12%2932% 3A4%3C 1750%3ARBC%3E2.0,CO%3B2-2

Journal of Economic Literature is currently published by American Economic Association.

‘Your use of the ISTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

hhup:/www.jstororg/about/terms.hml. JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you

have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and

you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

hup:/ www jstor.org/journalsaea.himl

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the sereen or

printed page of such transmission,

STOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of

scholarly journals, For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact support @jstor.org.

hupulwww jstor.org/

‘Tue Sep 7 10:22:12 2004

Journal of Economics Literatute

Vol. XXXII (December 1994), pp. 1750-1783

Real Business Cycles

By GEORGE W. STADLER

University of Newcastle upon Tyne

T have received numerous valuable comments from many indi-

viduals, comprising a list that is

ut special thanks are due to Jeremy Greenwood an

too long to acknowledge here,

David

Laidler, I also wish to acknowledge the excellent comments I re-

ceived from the reviewers, which also substantially improved this

article.

1. Introduction

HE 1970s saw a distinctive shift in

macroeconomic research. The tradi-

jonal Keynesian research program was

concerned with the determination of

output and employment at a point in

time and with how to alter and stabilize

the time paths of major macroeconomic

variables. In the 1970s this research pro-

gram increasingly gave way to business

cycle theory, that is, the theory of the

nature and causes of economic fluctua-

tions. This paper is a summary and as-

sessment of Real Business Cycle (RBC)

theory.!

1 There have been a numberof surveys of Real

Bosiness Cele “Theory, inhndng TetsPere

Danthine and John Donaldson (1988) Chan Huh

and. Bharat frehan (1991), Grogory Mankiw

(i960), and Bennett McCallum (1980) These sure

‘eye donot always consider recent developments

{nd extensions, which have. gone. some Way to

wards migatg some of the early crits of

this theory"However, even where they do consider

‘evelopment, they tend to focus on pa.

‘pects of REC research, For example,

Danthine and Donaldson focus on developments

Concerning the labor market, while Huh and Tre

isan focus on the ole of money Jn these: models

Anyone interested tn further reading on business

The development of the New Classical

macroeconomics brought about the re-

vival of business eycle theory. The New

Classical paradigm tried to account for

the existence of eycles in perfectly com-

petitive economies with rational expecta-

tions. It emphasized the role of imper-

fect information, and saw nominal

shocks, in the form of monetary misper-

ceptions, as the cause of cycles. The New

Classical theory posed a challenge to

Keynesian economics and stimulated the

development of both the New Keynesian

economics and RBC theory. The New

Keynesian economies has generally ae-

cepted the idea of rational expectations,

but emphasizes the importance of imper

fect competition, costly price adjustment

and externalities and considers nominal

shocks as the predominant impulse

mechanism.

RBC theory has developed alongside

cycles f refered to Thomas Cooley (ortheom-

ingl, which covers a number of areas of RBC Te-

srl ta re eth ayy oh

sey, ih greater depth, and provides an excellent

invoduction to the techniques required for bud:

ing RBC modet.

Stadler: Real Business Cycles

the New Keynesian economies, but,

unlike it, RBC theory views cycles as

arising in frictionless, perfectly competi-

tive economies with generally complete

markets subject to real shocks. RBC

models demonstrate that, even in such

environments, cycles can arise through

the reactions of optimizing agents to real

disturbances, such as random changes in

technology or productivity.? Further-

more, such models are capable of mim-

icking the most important empirical

regularities displayed by business cycles.

Thus, RBC theory makes the notable

contribution of showing that fluctuations

in economic activity are consonant with

competitive general equilibrium environ-

ments in which all agents are rational

maximizers. Coordination failures, price

stickiness, waves of optimism or’ pessi-

mism, monetary policy, or government

policy generally are not needed to ac-

count for business cycles.

The following section of the paper de-

seribes the background of RBC theory,

the key features of RBC models and out-

lines a simple, prototype RBC model.

Section III considers some of the many

recent developments that have built on

this basic RBC model. It finds that a

number of cyclical phenomena cannot be

explained by a model driven only by

technology shocks. Increasingly, this has

lead to the development of models

where technology shocks are supple-

mented by additional disturbances that

are analogous to taste shocks. It also as-

sesses extensions of the basic model that

incorporate money, government policy

4 An alternative way of classifying these models

ts through the location of the dominant impulee

driving the jeer do they arise on the demand

Side oF the supply side ofthe econouny? Now Cla

Sealand New Keynesian anodes are deen by da

tmandside shock, while HDGs are driven by up.

Phide. shocks Some writers question the

Tecilmes ofthis distinction, pointing out thet any

suppbyids innovation caunces hangs in demand

ane vers

1751

actions, and traded goods. Section IV ex-

amines the criticisms that have been lev-

eled against RBCs. The strongest criti-

cisms are first, there is no independent

corroborating ‘evidence for the large

technology shocks that are assumed to

drive business cycles and second, RBC

models have difficulty in accounting for

the dynamic properties of output be-

cause the propagation mechanisms they

employ are generally weak. Thus, while

RBC models can generate cycles, these

are, as a general rule, not like the cycles

observed. Section V surveys the empiri-

cal evidence, and finds little to mitigate

these criticisms. The final section sums

up, and considers the challenges that

RBC theory still faces. The strong aggre-

gation assumptions these models make

by relying on representative agents cast

doubt on their ability to assess. policy

questions, and also on their claim to have

provided a more rigorous microfounda-

tion for macroeconomics than competing

paradigms.

IL. The Basic Real Business Cycle Model

A. Historical Background and

Development

Business cycles vary considerably in

terms of amplitude and duration, and no

two cycles appear to be exactly ali

Nevertheless, these cycles also contain

qualitative features or regularities that

persistently manifest themselves. Among

the most prominent are that output

movements in different sectors of the

economy exhibit a high degree of coher-

ence; that investment, or production of

durables generally, is far more volatile

than output; consumption is less variable

than output; and the capital stock much

less variable than output (Robert Lucas

1977). Velocity of money is countereycli-

cal in most countries, and there is con-

siderable variation in the correlation be-

tween monetary aggregates and output

1752

(Danthine and Donaldson 1993). Long-

term interest rates are less volatile than

short-term interest rates, and the latter

are nearly always positively correlated

with output, but the correlation of longer-

term rates with output is often negative

or close to zero. Prices appear to be

countercyclical, but I argue below that

this evidence is tenuous. Employment is

approximately as variable as output,

while productivity is generally less vari-

able than output, although certain coun-

tries show deviations from this pattern.

RBC models demonstrate that at least

1 of these characteristics can be rep-

ed in competitive general equilib-

rium models where all agents maximize

and have rational expectations. Further-

more, this research program originated

in the U.S.A. and usually American data

have been used as the benchmark against

which these models are judged.

Real Business Cyclé theory regards

stochastic fluctuations in factor produc-

tivity as the predominant source of fluc-

tuations in economic activity. These

theories follow the approach of Ragnar

Frisch (1933) and Eugen Slutzky (1937),

which clearly distinguishes between the

impulse mechanism that initially causes a

variable to deviate from its steady state

value, and the propagation mechanism,

which causes deviations from the steady

state to persist for some time. Exogenous

productivity shocks are the only impulse

mechanism that these models originally

incorporated. Other impulse mecha-

nisms, such as changes in preferences,?

Taste oF preference shocks, by themselves,

cannot explain eles, Olivier Jean Blancl

Staley locher (080b, p.'80) argue th

equilibrium framework, fast shoes Tead to large

Fidetustions in consumption relative to output Gn

realty consumption inch ey aril than ot

ut) and Fall to generat the procylical movement

Miaventores and tavestment that Is observed in

the dt Furthermore dificult to bive that

‘most agent suffer recurrent changes in their pref

trences that are large enough to drive eyees,

Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XXXII (December 1994)

or tax rates, or monetary policy, have

been generally regarded by RBC theo-

rists as having at best minor influence on

the business cycle. It is this emphasis on

productivity changes as the predominant

source of cyclical activity that distin-

guishes these models from their pre-

decessors and rivals. In particular, the

absence of a role for demand-side inno-

vations coupled with the assumption of

competitive markets marks a clear break

from the traditional Keynesian theory

where changes in investment, consump-

mn, oF government spending are the

main determinants of output in the short

run,

The importance of exogenous produe-

tivity changes in economie theory can be

traced to the seminal work of Robert

Solow (1956, 1957) on the neoclassical

growth model that appeared in the

1950s. Solow postulated a one-good

‘economy, in which the capital stock is

merely the accumulation of this compos-

ite commodity. The technical possibili-

ties facing the economy are captured by

a constant returns to scale aggregate pro-

duction funetion. Technical progress

proceeds at an exogenous rate in. this

theory, and augments the productivity of

labor. (Technical change is Harrod neu-

tral, so ensuring the constancy of relative

shares and sustained steady-state

growth.)

However, it is Solow’s work on esti-

mating the sources of economic growth

that has proved most influential in the

RBC literature. If markets are competi-

tive and there exist constant returns to

scale, then the growth of output from

the aggregate production function is:

By = Og + (1 ean +2,

where g,, g1 and gy are the growth rates

of output, labor, and capital respectively,

Gis the relative share of output of labor,

and z measures the growth in output that

cannot be accounted for by growth in la-

Stadler: Real Business Cycles

bor and capital. Thus z represents multi-

factor productivity growth and has been

dubbed the “Solow residual.” Rearrang-

ing the above equation one obtains:

@-00=(E9)ig- 4) + (Ware

This states that growth of output per

capita depends on the growth of the

capital-output ratio and on the Solow re-

sidual, z. The Solow residual has ac-

counted for approximately half the

growth in output in the U.S.A. since the

1870s (Blanchard and Fisher 1989b, pp.

3-5). This residual is not a constant, but

fluctuates significantly over time, It is

well described as a random walk with

drift plus some serially uncorrelated

measurement error (Edward Prescott

RBC analysis. RBC theorists contend

that the same theory that explains long-

run growth should also explain business

cycles, Once one incorporates stochas-

tic fluctuations in the rate of technical

progress into the neoclassical growth

‘model, it is capable of displaying business

cycle phenomena that match reasonably

closely those historically observed in the

U.S.A. Thus, RBC theory can be seen as

‘a development of the neoclassical growth

theory of the 1950s,

B, The Basic Features of Real Business

Cyele Models

The evolution of RBC theory is nota-

ble for its emphasis on microfounda-

tions: macroeconomic fluctuations are

the outcome of maximizing decisions

made by many individual agents. To ob-

tain aggregates, one adds up the decision

outcomes of the individuel players, and

imposes a solution that makes those deci-

sions consistent.

1753

Typically, RBC models contain the fol-

lowing features:

i) They adopt a representative agent

framework, focusing on a representative

firm and household, and in so doing the

models circumvent aggregation prob-

lems

ii) Firms and households optimize ex-

plicit objective functions, subject to the

resource and technology constraints that

they face.

ili) The cycle is driven by exogenous

shocks to technology that shift produc-

tion functions up or down. The impact of

these shocks on output is amplified by

intertemporal substitution of

vise in productivity raises the cost of le

sure, causing employment to inerease,

iv) All agents have rational expecta-

tions and there is continuous market

clearing. There are complete markets

and no informational asymmetries.

v) Actual cycles are generated by pro-

viding a propagation mechanism for the

tffects oF shocks. This can take several

forms. First, agents generally seek to

smooth consumption over time, so that a

rise in output will manifest itself partly

as a rise in investment and in the capital

stock. Second, lags in the investment

process can result in a shock today af-

fecting investment in the future, and

thus future output. Third, individuals

will tend to substitute leisure intertem-

porally in response to transitory changes

in wages—they will work harder when

wages are temporarily higher and com-

pensate by taking more leisure once

‘wages fall to their previous level. Fourth,

firms may use inventories to meet unex-

pected changes in demand. If these are

depleted, then, if firms face rising mar-

ginal costs, they would tend to be re-

plenished only gradually, causing output

to rise for several periods.

The first propagation mechanism

likely to be weak, while focusing on

ventories yields negative serial correla-

1754

tion for output-output movements are

strongly positively serially correlated in

reality (Fischer 1988). Most RBC models.

focus on the second and third propage-

tion mechanisms.

The intertemporal substitution mecha-

nism is also likely to be weak. Most inno-

vations in technology are regarded as

highly persistent or even permanent,

rising the real wage permanently, This

is unlikely to eliet «large labor 5

response, because the substitution eRe

of the higher wage is likely to be offset

by the income effect. Only in response to

temporary shocks is significant intertem-

poral substitution likely to occur. How-

ever, to fit the data, RBC models assume

that most of the technology innovation is

highly persistent. This points to the gen-

cral difficulty of trying to reconeile ob-

served labor market data with a technol-

ogy driven equilibrium theory, and is

examined in more detail in Section ILA

below.

C. A Simple Prototype RBC Model

Consider an economy populated by

identical, infinitely lived agents that pro-

duce a single good as output. There are

no frictions or transactions costs, and, for

simplicity we abstract from the existence

of money and government. Each agent's

preferences are

o

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- 6Document48 pages6Luis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Risk Executive Committee Scotiabank: Lima, 25 de Septiembre 2020Document56 pagesRisk Executive Committee Scotiabank: Lima, 25 de Septiembre 2020Luis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet

- 5Document46 pages5Luis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet

- 4Document58 pages4Luis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Hodrick Prescott (1981)Document26 pagesHodrick Prescott (1981)Luis Antonio La Torre Quintero100% (1)

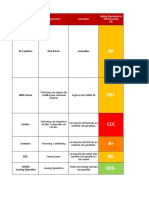

- Ffii Subyacentes Garantías Rating Equivalencia Internacional PDDocument4 pagesFfii Subyacentes Garantías Rating Equivalencia Internacional PDLuis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Blanchard Kahn (1980)Document8 pagesBlanchard Kahn (1980)Luis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Financiamiento Estructurado - Advance - CXC Utilities: FundamentosDocument10 pagesFinanciamiento Estructurado - Advance - CXC Utilities: FundamentosLuis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Silabo ModelosDSGE1 March2020Document3 pagesSilabo ModelosDSGE1 March2020Luis Antonio La Torre QuinteroNo ratings yet