Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3 Mandfractures

Uploaded by

Anggi PutriOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3 Mandfractures

Uploaded by

Anggi PutriCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/279757587

Pattern and Management of Mandibular Fractures: A Study Conducted on 264

Patients

Article · June 2007

CITATIONS READS

17 1,159

3 authors, including:

Syed Amjad Shah

Peshawar Dental College & Hospital

21 PUBLICATIONS 102 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

The relation of Peripheral Nerve injury with Maxillofacial Trauma View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Syed Amjad Shah on 06 July 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Mandibular Fractures

PATTERN AND MANAGEMENT OF MANDIBULAR FRACTURES:

A STUDY CONDUCTED ON 264 PATIENTS

*AMJAD SHAH, FCPS (Pak)

**ADNAN ALI SHAH, MDS (UK), FRACDS (Aus), FDSRCS (London)

***ABDUS SALAM, MDS, FCPS (Pak)

ABSTRACT

The descriptive study was undertaken to determine the pattern and different methods of

treatment of maxillofacial fractures. Two hundred and sixty four patients with mandibular fractures

were treated during the year 2001-2002. A review of patients’ records and radiographs was conducted.

Data regarding age, gender, cause of fracture, anatomic site and treatment modalities were reviewed.

There was higher prevalence in male (4.8:1), with occurrence peak between 21-30 years. The principal

causes of fracture in this study were RTA (Road Traffic Accidents) representing 62.8%(n=166), followed

by fall (n=53; 20%), assault, sports, Fire Arm Injury (FAI). The most injured sites were, in decreasing

order, body of the mandible (30.3%) followed by condylar region (24.2%), angle, paraymphysis,

dentoalveolar, symphysis, ramus, coronoid. Most patients of mandibular fractures were treated by

closed reduction [eyelet wiring, arch bars with intermaxillary fixation (IMF) & splint fixation], 18.9%

of patients were treated with open reduction (Interosseous & miniplates fixation. This study reflects

patterns of mandibular fracture within the community and, it is hoped that assessment presented here

will be valuable to government agencies and health care professionals involved in planning future

programs of prevention & treatment.

Key words: Trauma, Mandibular fractures, facial fractures, Etiology

INTRODUCTION restored bone losses, with dental occlusion affection or

temporomandibular joint disorder. If not identified or

The mandible is a unique bone having a complex inappropriately treated, these lesions may lead to

role in aesthetics of the face and functional occlusion. severe sequelae, both cosmetic and functional.1,2

Because of the prominent position of the lower jaw,

mandibular fractures are the most common fractures It has been reported that fractures of the mandible

of the facial skeleton. Given that the mandible is the account for 36% to 59% of all maxillofacial fracture.3-5

only facial bone that has mobility and the remaining The large variability in reported prevalence is due to a

portion is part of the fixed facial axis, the fracture is variety of contributing factors such as gender, age,

never left unnoticed because it is very painful, pain that environment, and socio-economic status of patient, as

worsens with mastication and phonation movements, well as the mechanism of the injury. The most

and even respiratory movements; sometimes there are favourable site of fracture( in descending order) in

facial asymmetry complaints. Mandible fractures may mandible are the body, angle, condylar region, symphy-

lead to deformities be them by displacement or non- sis, and coronoid process.

* Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeon, Dentistry Department PGMI/Govt Lady Reading Hospital, Peshawar

** Professor & Head Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery de,Montmorency College of Dentistry,

Punjab Dental Hospital, Lahore

*** Professor & Head Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery/Principal Khyber College of Dentistry,

Peshawar

Correspondence: Dr. Amjad Shah, Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeon, Dentistry Department PGMI/Govt Lady

Reading Hospital, Peshawar, Mobile: 0333-9107122, E-mail: amjadshahsyed@yahoo.com

Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal Vol 27, No. 1 103

Mandibular Fractures

Treatment of mandibular fractures has changed No of cases Percent

over the last 20 years. There has been a decrease in the

RTA 166 63

use of wire osteosynthesis and intermaxillary fixation

and an increase in preference for open reduction and Fall 53 20

internal fixation with miniplates.6,7 This has helped to Assault 26 10

reduce malocclusion, non-union, improved mouth open-

ing, speech, oral hygiene, decrease loss and the ability Sports 16 6

for patients to return to work earlier.6,8 FAI 3 1

The aim of the study was to examine the pattern Total 264 100

and treatment of mandibular fractures. A clearer un- TABLE 1: DISTRIBUTION OF MANDIBULAR

derstanding of pattern of mandibular fractures will FRACTURES ACCORDING TO ETIOLOGY

assist health care providers as they plan and manage

the treatment of traumatic maxillofacial injuries. Such Approximately 15% cases involved combination

information can also be used to guide the future fractures (2.65% sustained fractures of both Mandible

funding of public health programmer geared toward and Maxilla whereas Zygoma is involved in 12.97%(n=34)

prevention. of patients with mandibular fractures). The distribu-

tion of the mandibular fractures is detailed in tables 2,

MATERIALS AND METHODS 3. The most common site was body of the mandible

(30.3%), followed by condylar process (24.2%), angle

The records and radiographs of all patients were (21.6%), parasymphysis (10.6%), dentoalveolar (5.7%)

reviewed who have presented with mandibular frac- symphysis (4.9%), ramus (1.9%) and the coronoid pro-

tures to the department of Oral and Maxillofacial cess (8%).

Surgery, de Montmorency College of Dentistry, Punjab

Dental Hospital Lahore, from June 2001 to Dec 2002.

No of Percent

Punjab Dental Hospital is a tertiary care hospital

cases

serving central Punjab’s demographically diverse popu-

lation. All patients treated for mandibular fracture, Mandibular Fractures alone 223 84.4

whether admitted to hospital and treated in operating Mandible and Maxilla 7 2.65

room or seen as outpatients, were included in this

Mandible and Zygomatic Complex 34 12.97

investigation. Patient information was collected by

proforma specially designed for this purpose. The Total 264 100

fractures were classified according to standard nomen-

TABLE 2: DISTRIBUTION OF MANDIBULAR

clature. An appropriate management plan was devised

FRACTURES

and followed up for 6-weeks. The mandibular fractures

were compiled according to age, gender, etiology,

Number Percent

anatomic site and methods of fixation.

of cases

RESULTS Body 80 30.3

Condyler 64 24.2

In the studied period, mandibular fractures were

diagnosed in 264 patients. The main cause of mandibu- Angle 57 21.6

lar fractures in the study was RTA (n=166; 63%). Falls Parasymphysis 28 10.6

were the second most frequent causative factor of

Dentoalveolar 15 5.7

fractures (n=53; 20%), followed by fight (n=26; 10%),

sports (n=16; 6%). The causes of mandibular fractures Symphysis 13 4.9

are listed in table 1. Ramus 5 1.9

By crosschecking the data collected from age and Coronoid 2 0.8

gender, we detected a predominance of male gender Total 264 100.0

cases in all age ranges, mean of approximately 4.8:1,

we also found a peak occurrence in young adults, age TABLE 3: DISTRIBUTION OF MANDIBULAR

21-30 years. FRACTURES ACCORDING TO ANATOMIC SITE

104 Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal Vol 27, No. 1

Mandibular Fractures

Several methods of reduction and fixation were When the maxillofacial region is injured, the man-

used in the treatment of mandibular fractures as dible is more vulnerable than the midface fractures.17

shown in table 4. Of the 264 mandibular fractures, 214 This could be because the mandible is mobile and has

cases (81%) were treated by closed reduction; 106(40.2%) less bony support than midfacial bones. These frac-

of these with IMF (eyelet wiring), 65(24.6%) with arch tures are, however, more common in certain sites of

bars and IMF used to treat condylar fractures, 28(10.6%) the mandible than others. Almost all studies showed

with splint fixation mostly used for children and eden- that the body of the mandible was the most frequently

tulous patients. 50 (19%) patients were treated by open affected area. The least affected site is the coronoid

reduction and fixation with interosseous wiring and process.

miniplates.

In this study condyler region of the mandible is the

Number Percent 2nd most commonly involved site, which is in contrast

of cases with figures obtained from studies in Nigeria18 and

IMF (eyelet wiring) 106 40.2 Jordan.10 It is difficult to cite a reason for this differ-

ence; perhaps further study on the causes of the

IMF (arch bar+elastics) 65 24.6 regional mandibular fractures would be useful. One

Splint fixation 28 10.6 can speculate that inter-population difference in the

sites of mandibular fractures partly related to the

Interosseous wiring 28 10.6

with IMF diverse etiologic factors involved.

Miniplates fixation 22 8.3 There are many different therapeutic possibilities,

with IMF given that many author disagree about the best treat-

Plain arch bar 15 5.7 ment approach. Regardless of the type of fracture and

treatment, we should achieve anatomical reduction by

Total 264 100.0 positioning the teeth and precisely readjusting bone

TABLE 4: TREATMENT MODALITIES fragment for appropriate treatment, whose main objec-

FOR MANDIBULAR FRACTURES tive is to maintain mandible function19. Therefore, the

objectives of the therapy are: mandible symmetry,

DISCUSSION absence of pain or cracking upon TMJ palpation with

closed and opened mouth, satisfactory dental occlu-

The mandible is the only mobile bone of the face sion, maximum interincisal opening greater than 40mm,

and it participates in basic function such as mastica- and absence of midline deviation or deviation smaller

tion, phonation, swallowing and maintenance of dental than 2mm at mouth opening.20

occlusion.1 Despite the fact that it is the heaviest and

strongest facial bone, the mandible is prone to frac- Several studies have suggested that most

tures for some specific reason: 1) it is an open arch; 2) mandibular fractures can be treated by closed reduc-

it is located in the lower portion of the face; 3) it is the tion and I.M.F. Olson et al21 and Hill et al22 concluded

mechanism of hyperextension and hyperflection of the that most mandibular fractures were amenable to

head in traffic accidents; 4) it gets atrophy as a result management by Closed Reduction. Of the 264 patients

of aging.9 in our series, 50 cases of mandibular fractures

had required open reduction. All methods were used

The results of this investigation of patients with for fixation without the use of any devices for exter-

mandibular fractures are largely in agreement with nal fixation. Furthermore, simple methods of

those of previous reports particularly with regard to Reduction and Immobilization were used on outpatient

age and gender of the patients. The finding that age basis under local anesthesia. And the results were

group 21-30 years constituted the group with the satisfactory.

highest frequency of jaw fractures is consistent with

previously published reviews.10-15 It has also been con- In recent years, there has been a trend towards

sistently shown that the frequency of mandibular rigid fixation with miniplates. In our study 22 cases

fractures among male is far grater than that of female. (8.3%) were treated with miniplates. The postoperative

Reported overall ratios of male to female have ranged results were satisfactory. Most of the patients belong to

from 3:1 to 5.4:14,5,10,14 similar to the ratio observed here low socio-economic status; therefore, limited numbers

(4.8:1). of cases were selected for miniplate fixation.

Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal Vol 27, No. 1 105

Mandibular Fractures

CONCLUSION & RECOMMENDATIONS 16 Voss R. The etiology of jaw fractures in Norwegian patients.

J Maxillofac Surg 1982; 10:146-8.

In the present study, the mandibular fractures 17 Shahid H, Ahmad M, Khan I, Anwar M, Amin M, Sumera et

al. Maxillofacial Trauma: Current practice in management at

were more prevalent in male patients and during the Pakistan institute of medical sciences. J Ayub Med Coll

3rd decade of life. The most common cause was RTA and Abottabad 2003; 15: 8-11.

the more frequently affected regions were body and 18 Oji C. Jaw fractures in Enugu, Nigeria, 1985-95. Br J Oral

condyle. Isolated mandibular fracture occure in more Maxillofac Surg 1999; 37:106-9

19 Gilmer TL. A case of fracture of the lower jaw with remarks

than 80% of cases. Most patients were treated with

on the treatment. Arch Dent 1887; 4:388.

closed reduction and conventional means. 20 Gilmer TL. Fractures of inferior maxilla. Ill St Dent Soc Trans

1881; 67:67.

It is hoped that assessments such as the one 21 Olson RA, Fonseca RJ, Zeitler DL, Osbon DB. Fractures of the

presented here will be valuable to the government mandible: a review of 580 cases. J oral Maxillofac Surg 1982;

agencies and health care professionals involved in 40: 23-8.

planning futures programmes of prevention and treat- 22 Hill CM, Crosher RF, Carroll MJ, Mason DA. Facial fractures:

the results of a prospective four years study. J Maxillofac Surg

ment. 1984; 12:267-70.

23 Stacey DH, Doyle JF, Mount DL, Snyder MC, Gutowski KA.

REFERENCES Management of mandible fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg

2006; 117: 48e-60e.

1 Busuito MJ, Smith Jr, Robson MC. Mandibular fractures in an 24 Sakr K, Farag IA, Zeitoun IM. Review of 509 mandibular

urban trauma center. J Trauma 1986; 26:826-9. fractures treated at the University Hospital, Alexandria,

2 Olson B, Fonseca RJ, Zeitler DL, et al. Fractures of the Egypt. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006; 44:107-11.

mandible: A review of 580 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1982; 25 Oikarinen K, Schutz P,Thalib L, Sandor GK, Clokie C, Meisami

40:23-8. T, Safar S, Moilanen M, Belal M. Differences in the etiology

3 Brook IM, Wood N. Aetiology and incidence of facial fractures of mandibular fractures in Kuwait, Canada, and Finland. Dent

in adults. Int J Oral Surg 1983; 12:193-8. Traumatol 2004; 20:241-5.

4 Ellis E 3rd, Moos KF, el-Attar A. Ten years of mandibular 26 King RE, Scianna JM, Petruzzelli GJ. Mandible fracture

fractures: an analysis of 2137 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral patterns: a suburban trauma center experience Am J

Pathol 1985; 59:120-9. Otolaryngol 2004; 25:301-7.

5 Von Hoof Rf, Merkx CA, Stekelenbrug EC. The different 27 Unnewehr M, Homann C, Schmidt PF, Sotony P, Fischer G,

patterns of fractures of the facial skeletonin European coun- Brinkmann B, Bajanowki T, DuChesne A. Fracture proper-

tries. Int J Oral Surg 1977; 6: 3-11. ties of the human mandible. Int J Legal Med 2003; 117:

326-30.

6 Rix L, Stevenson ARL, Punnia-Moorthy A. An analysis of 80

cases of mandibular fractures treated with miniplates osteo- 28 Qudah MA, Al- Khateeb T, Bataineh AB, Rawashdeh MA.

synthesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991; 20:337-41. Mandibular fractures in Jordanians: a comparative study

between young and adult patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg

7 Renton TF, Wiesenfeld D, Mandibular fractures osteosynthe-

2005; 33:103-6.

sis: a comparison of three technique. Br J Oral Maxillifac Surg

1996; 34:166-73. 29 Ogundare BO, Bonnick A, Bayley N. Pattern of mandibular

fractures in an urban major trauma center. J Oral Maxillofac

8 Hayter JP, Cawood JI. The functional case for miniplates in

Surg 2003;61:713-8.

maxillofacial surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993; 22:

91-96. 30 Remi M, Christine MC, Gael P, Soizick P, Joseph AJ. Mandibu-

lar fractures in children: long term results. Int J Pediatr

9 Holt RG, Maxillofacial Trauma. In: Otolarygology Head and

Otorhinolaryngol 2003; 67: 25-30

Neck Surgery. Mosby Company.19: 313-4,1986.

10 Bataineh AB. Etiology and incidence of maxillofacial fractures 31 Dongas P, Hall GM. Mandibular fracture patterns in Tasma-

in the north of Jordan. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral nia, Australia. Aust Dent J 2002; 47:131-7.

Radiol Endod 1998; 86: 31. 32 Sojot AJ Meisami T, Sandor GK, Clokie CM. The epidemiology

11 Ugboko VI, Oduanya SA, Fagade OO. Maxillofacial fractures of mandibular fractures treated at the Toronto general hos-

in a semi-urban Nigerian teaching hospital. A review of 442 pital: A review of 246 cases. J Can Dent Assoc 2001; 67:

cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 27: 286-9. 640-4.

12 Tanaka N, Tomitsuka, Shionoya K, Andou, Kimjim Y, Tashiro 33 Wong KH. Mandible fractures: a 3-year retrospective study of

T, et al. Aetiology of maxillofacial fractures. Br J Oral Maxillofac cases seen in an oral surgical unit in Singapore. Singapore

Surg 1994; 32:19-23. Dent J 2000; 23: 6-10.

13 Heimdahl A, Nordenram A. The first 100 patients with jaw 34 Patrocinio LG, Patrocinio JA, Borba BH, Bonatti BS, Pinto LF,

fractures at the Department of Oral Surgery, Dental school, Vieira JV, Costa JM. Mandibular fracture: analysis of 293

Huddinge. Swed Dent J 1977; 1; 177-82. patients treated in the Hospital of Clinics, Federal University

14 Marker P, Nielsoen A, Bastian HL. Fractures of the mandibu- of Uberlandia: Rev Bras otorrinolaringol 2005; 71: 256-5.

lar condyle. Part 2: Result of treatment of 348 patients. Br J 35 Sidal T, Curti DA. Fractures of the mandible in the aging

Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000;38:422-6. population. Spec Care Dentist 2006; 26:145-9.

15 Adi M, Ogden G R, Chisholm D M. An analysis of mandibular 36 Imazawa T, Komuro Y, Inoue M, Yanai A. Mandibular frac-

fractures in Dundee, Scottland (1977 to 1985). Br J Oral tures treated with maxillomandibular fixation screws (MMFS

Maxillofac Surg 1990; 28:194-99. method). J craniofac Surg 2006; 17: 544-9.

106 Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal Vol 27, No. 1

View publication stats

You might also like

- Peri-Implant Complications: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and TreatmentFrom EverandPeri-Implant Complications: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and TreatmentNo ratings yet

- 13 Samira AjmalDocument6 pages13 Samira AjmalMuhammad RizqiNo ratings yet

- 2021 Incidence and Pattern of Mandible Fractures An Urban Tertiary Care Centre ExperienceDocument5 pages2021 Incidence and Pattern of Mandible Fractures An Urban Tertiary Care Centre ExperienceSatisha TSNo ratings yet

- Open Reduction With Internal Fixation of Mandibular Angle Fractures: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesOpen Reduction With Internal Fixation of Mandibular Angle Fractures: A Retrospective StudyRudnapon AmornlaksananonNo ratings yet

- Parameters Deciding Orthognathic Surgery or Camouflage? - A ReviewDocument8 pagesParameters Deciding Orthognathic Surgery or Camouflage? - A ReviewDr. Sagar S BhatNo ratings yet

- Fixation of Mandibular Fractures With 2.0 MM MiniplatesDocument7 pagesFixation of Mandibular Fractures With 2.0 MM MiniplatesRajan KarmakarNo ratings yet

- Zygomatico-Maxillary Complex Fractures: A Retrospective Study On Etiology, Pattern and ManagementDocument12 pagesZygomatico-Maxillary Complex Fractures: A Retrospective Study On Etiology, Pattern and ManagementSweet SumanNo ratings yet

- Zygomatico-Maxillary Complex Fractures: A Retrospective Study On Etiology, Pattern and ManagementDocument12 pagesZygomatico-Maxillary Complex Fractures: A Retrospective Study On Etiology, Pattern and ManagementSweet SunNo ratings yet

- Al-Dumaini - 2018 - A Novel Approach For Treatment of Skeletal Class II Malocclusion - Miniplates-Based Skeletal AnchorageDocument9 pagesAl-Dumaini - 2018 - A Novel Approach For Treatment of Skeletal Class II Malocclusion - Miniplates-Based Skeletal AnchoragefishribbonNo ratings yet

- Complications in The Use of The Mandibular Body, Ramus and Symphysis As Donor Sites in Bone Graft Surgery. A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesComplications in The Use of The Mandibular Body, Ramus and Symphysis As Donor Sites in Bone Graft Surgery. A Systematic ReviewBrenda Carolina Pattigno ForeroNo ratings yet

- Ongodia 2014Document4 pagesOngodia 2014Sung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S027823911501438XDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S027823911501438Xhyl776210No ratings yet

- Occurrence and Type of Complications Associated With Mandibular Bilateral Removable Partial Denture: Prospective Cohort DataDocument7 pagesOccurrence and Type of Complications Associated With Mandibular Bilateral Removable Partial Denture: Prospective Cohort DataIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Trendsand Outcomesof Managementof Mandibular FracturesDocument8 pagesTrendsand Outcomesof Managementof Mandibular FracturesVincent AriesNo ratings yet

- Treatment Effects After Maxillary Expansion Using Tooth-Borne Vs Tissue-Borne Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion ApplianceDocument9 pagesTreatment Effects After Maxillary Expansion Using Tooth-Borne Vs Tissue-Borne Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion ApplianceRolando Huaman BravoNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Prosdent 2019 06 018Document10 pages10 1016@j Prosdent 2019 06 018Mayank AggarwalNo ratings yet

- 1548-1336 (2004) 030 0030 Aocarc 2 0 Co 2Document10 pages1548-1336 (2004) 030 0030 Aocarc 2 0 Co 2waf51No ratings yet

- 2021 Does The Timing of 1-Stage Palatoplasty With Radical Muscle Dissection Effect Long-Term Midface Growth A Single-Center Retrospective AnalysisDocument7 pages2021 Does The Timing of 1-Stage Palatoplasty With Radical Muscle Dissection Effect Long-Term Midface Growth A Single-Center Retrospective AnalysisDimitris RodriguezNo ratings yet

- KeypointsDocument8 pagesKeypointsMaydith Tarazona MelgarejoNo ratings yet

- MidfaceDocument12 pagesMidfacedehaaNo ratings yet

- Oral and Maxillofacial SurgeryDocument5 pagesOral and Maxillofacial SurgeryGabriel LazarNo ratings yet

- Bone GraftDocument4 pagesBone Graftsmansa123No ratings yet

- Correcting Severe Scissor Bite in An Adult: Case ReportDocument12 pagesCorrecting Severe Scissor Bite in An Adult: Case ReportLikhita ChNo ratings yet

- Etiology, Distribution, Treatment Modalities and Complications of Maxillofacial FracturesDocument9 pagesEtiology, Distribution, Treatment Modalities and Complications of Maxillofacial FracturesPinguin SatuNo ratings yet

- Management of Sub Condylar Fracture in 15 Yr Old Patient: Case ReportDocument6 pagesManagement of Sub Condylar Fracture in 15 Yr Old Patient: Case ReportIma ShofyaNo ratings yet

- Management of Zygomatic Fractures: A National SurveyDocument5 pagesManagement of Zygomatic Fractures: A National Surveystoia_sebiNo ratings yet

- JPM 12 00508 PDFDocument9 pagesJPM 12 00508 PDFMans TvNo ratings yet

- Management of Maxillofacial Fracture: Experience of Emergency and Trauma Acute Care Surgery Department of Sanglah General Hospital Denpasar BaliDocument4 pagesManagement of Maxillofacial Fracture: Experience of Emergency and Trauma Acute Care Surgery Department of Sanglah General Hospital Denpasar Balisiti rumaisaNo ratings yet

- Sinha 2020Document10 pagesSinha 2020ABKarthikeyanNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors in Early Implant Failure: A Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesRisk Factors in Early Implant Failure: A Meta-AnalysisstortoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0278239108011452 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0278239108011452 MainAshish VyasNo ratings yet

- Journal Endang - Ijsr Juli 2020, Fracture MandibleDocument5 pagesJournal Endang - Ijsr Juli 2020, Fracture MandibleEndang Samsudin FKGNo ratings yet

- 2005 J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005-63-1567 Marx Bisphosphonate InduDocument9 pages2005 J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005-63-1567 Marx Bisphosphonate InduVerónica RuizNo ratings yet

- Deep Bite Malocclusion - Exploration of The Skeletal and Dental FaDocument7 pagesDeep Bite Malocclusion - Exploration of The Skeletal and Dental FaR. Yair Delgado JaimesNo ratings yet

- El Tratamiento de Las Fracturas Del Ángulo MandibularDocument8 pagesEl Tratamiento de Las Fracturas Del Ángulo MandibularCristhian ChanaméNo ratings yet

- Shaft of Humerus Fracture Managed by Anteromedial Plating Through Anterolateral ApproachDocument5 pagesShaft of Humerus Fracture Managed by Anteromedial Plating Through Anterolateral ApproachMukesh KumarNo ratings yet

- 2176 9451 Dpjo 24 05 52Document8 pages2176 9451 Dpjo 24 05 52Crisu CrisuuNo ratings yet

- Jawline Contouring AlfaroDocument5 pagesJawline Contouring AlfaroÂngelo Rosso LlantadaNo ratings yet

- Journal Analysis of Fractured MandibleDocument5 pagesJournal Analysis of Fractured MandiblePrazna ShafiraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S088954061001005X MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S088954061001005X MainPanaite TinelaNo ratings yet

- Current Practice For Transverse Mandibular and Maxillary Discrepancies in The NetherlandsDocument10 pagesCurrent Practice For Transverse Mandibular and Maxillary Discrepancies in The NetherlandsDONGXU LIUNo ratings yet

- Disadvantages RmeDocument6 pagesDisadvantages RmeSiwi HadjarNo ratings yet

- 16 Influence of Bruxism On Survival of Porcelain Laminate Veneers PDFDocument7 pages16 Influence of Bruxism On Survival of Porcelain Laminate Veneers PDFLouwis MarquezNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Kanistika Jha, Manoj AdhikariDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Kanistika Jha, Manoj AdhikariYeraldin EspañaNo ratings yet

- Navigating The Gray Area: Managing Borderline Cases in OrthodonticsDocument6 pagesNavigating The Gray Area: Managing Borderline Cases in OrthodonticsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- ArticulosDocument7 pagesArticuloslupita.sm1988No ratings yet

- Zygomatic Bone FracturesDocument5 pagesZygomatic Bone FracturesAgung SajaNo ratings yet

- Rapid Maxillary Expansion. Is It Better in The Mixed or in The Permanent Dentition?Document8 pagesRapid Maxillary Expansion. Is It Better in The Mixed or in The Permanent Dentition?Gustavo AnteparraNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Three Different Types of Implant-Supported Fixed Dental ProsthesesDocument11 pagesComparison of Three Different Types of Implant-Supported Fixed Dental ProsthesesIsmael LouNo ratings yet

- Multidetector Coputed Tomographic Evaluation of Maxilofacial TraumaDocument5 pagesMultidetector Coputed Tomographic Evaluation of Maxilofacial TraumaDwi PascawitasariNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Retromandibular TransparotDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Retromandibular TransparotbhannupraseedhaNo ratings yet

- CPFSDocument7 pagesCPFSSASIKALANo ratings yet

- Embrasure Wire Tracy and GuttaDocument6 pagesEmbrasure Wire Tracy and Gutta6hd6mnrzw2No ratings yet

- Berlin Et Al (2023) Multidisciplinary Approach For Autotransplantation and Restoration of A Maxillary PremolarDocument7 pagesBerlin Et Al (2023) Multidisciplinary Approach For Autotransplantation and Restoration of A Maxillary PremolarISAI FLORES PÉREZNo ratings yet

- 31MDI RET '17 JacksonDocument6 pages31MDI RET '17 Jacksoncd.brendasotofloresNo ratings yet

- Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion: A Literature ReviewDocument13 pagesSurgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion: A Literature ReviewRahulLife'sNo ratings yet

- Sadowsky 2007Document9 pagesSadowsky 2007barbara buhlerNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between Intermaxillary Fixation With Screws and An Arch Bar For Mandibular FractureDocument3 pagesComparison Between Intermaxillary Fixation With Screws and An Arch Bar For Mandibular Fracture6hd6mnrzw2No ratings yet

- Treatment of Class II Malocclusion With Mandibular Skeletal AnchorageDocument9 pagesTreatment of Class II Malocclusion With Mandibular Skeletal AnchorageAnonymous 9PcFdakHcNo ratings yet

- Deep Bite Malocclusion: Exploration of The Skeletal and Dental FactorsDocument6 pagesDeep Bite Malocclusion: Exploration of The Skeletal and Dental FactorsSofeaNo ratings yet

- Post Parturition Back PainDocument35 pagesPost Parturition Back PainARF TYONo ratings yet

- Anatomy 2Document15 pagesAnatomy 2christinejoanNo ratings yet

- Ab Rehab Guide 2019Document15 pagesAb Rehab Guide 2019maria jose100% (3)

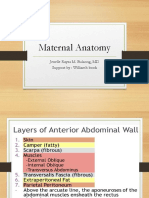

- Maternal Anatomy WilliamsDocument60 pagesMaternal Anatomy WilliamsZari Novela100% (2)

- PatellofemuralDocument216 pagesPatellofemuralandrei_costea100% (2)

- Kai Greene Leg Workout PDFDocument2 pagesKai Greene Leg Workout PDFHarith SimonNo ratings yet

- Pressure Ulcer Staging CardDocument2 pagesPressure Ulcer Staging CardMary RiveroNo ratings yet

- Late Swing or Early Stance? A Narrative Review of Hamstring Injury Mechanisms During High Speed RunningDocument9 pagesLate Swing or Early Stance? A Narrative Review of Hamstring Injury Mechanisms During High Speed Runninggaston9reyNo ratings yet

- Working With Hip Mobility (Myofascial Techniques)Document4 pagesWorking With Hip Mobility (Myofascial Techniques)Advanced-Trainings.com100% (2)

- Coaching Manual Level2 PDFDocument242 pagesCoaching Manual Level2 PDFleanabel77100% (1)

- Chiropractic Green Books - V09 - 1923Document582 pagesChiropractic Green Books - V09 - 1923Fernando BernardesNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of NeckDocument100 pagesAnatomy of NeckdiptidigheNo ratings yet

- Fixation of The Distal Tibiofibular Bone-Bridge in Transtibial Amputation PDFDocument4 pagesFixation of The Distal Tibiofibular Bone-Bridge in Transtibial Amputation PDFThomas BowersNo ratings yet

- Frozen Shoulder (Buku Komplit Etiologi DLL)Document7 pagesFrozen Shoulder (Buku Komplit Etiologi DLL)Ricky Diah Ayu AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Course Content 1st Year DPT (1st Semester)Document20 pagesCourse Content 1st Year DPT (1st Semester)KhanNo ratings yet

- Antagonistic PairsDocument1 pageAntagonistic PairsKasam ANo ratings yet

- CTEVDocument61 pagesCTEVSylvia LoongNo ratings yet

- Principles of Patient PositioningDocument62 pagesPrinciples of Patient PositioningMelody JusticeNo ratings yet

- Sport Injury and ManagementDocument56 pagesSport Injury and ManagementEva GustianiiNo ratings yet

- Movement Analysis ProjectDocument13 pagesMovement Analysis ProjectPatrickNo ratings yet

- Femoral Neck Fracture - Lembar BalikDocument24 pagesFemoral Neck Fracture - Lembar BalikAristyo RajaNo ratings yet

- Paley2002 Anatomical AxisDocument37 pagesPaley2002 Anatomical Axisprajwal guptaNo ratings yet

- Kinesiology of Shoulder ComplexDocument13 pagesKinesiology of Shoulder ComplexJaymin BhattNo ratings yet

- Cervical SpondylosisDocument25 pagesCervical Spondylosisjeevan ghimireNo ratings yet

- OsteoarthritisDocument29 pagesOsteoarthritisniekoNo ratings yet

- Osteoarthritis of The Knee Exercises PDFDocument4 pagesOsteoarthritis of The Knee Exercises PDFPooja jainNo ratings yet

- PerineumDocument5 pagesPerineumtechzonesNo ratings yet

- Determinants of GaitDocument35 pagesDeterminants of GaitAnup Pednekar50% (2)

- Sideline ManagementDocument60 pagesSideline ManagementkotraeNo ratings yet

- Proximal Phalanx Fracture Management 2018 PDFDocument8 pagesProximal Phalanx Fracture Management 2018 PDFMr BrewokNo ratings yet

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsFrom EverandAlgorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (722)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)