Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lassen 2008

Uploaded by

Kaliane BCCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lassen 2008

Uploaded by

Kaliane BCCopyright:

Available Formats

FEATURE

Allowing Normal Food at Will After Major Upper

Gastrointestinal Surgery Does Not Increase Morbidity

A Randomized Multicenter Trial

Kristoffer Lassen, MD, PhD,*† Jørn Kjæve, MD, PhD,*† Torunn Fetveit, MD,‡ Gerd Tranø, MD,§

Helgi Kjartan Sigurdsson, MD,¶ Arild Horn, MD, PhD,储 and Arthur Revhaug, MD, PhD*†

(5.0%) of 220 patients, respectively (P ⫽ 0.83). Time to resumed

Objective: The aim of this trial was to investigate whether a routine

bowel function was significantly in favor of allowing normal food at

of allowing normal food at will increases morbidity after major

will (P ⫽ 0.01), as were the total number of major complications,

upper gastrointestinal (GI) surgery.

length of stay, and rate of postdischarge complications.

Summary Background Data: Nil-by-mouth with enteral tube feed-

Conclusions: Allowing patients to eat normal food at will from the

ing is widely practiced for several days after major upper GI surgery.

first day after major upper GI surgery does not increase morbidity

After other abdominal operations, normal food at will has been

compared with traditional care with nil-by-mouth and enteral feeding.

shown to be safe and to improve gut function.

Methods: Patients were randomly assigned to a routine of nil-by- (Ann Surg 2008;247: 721–729)

mouth and enteral tube feeding by needle-catheter jejunostomy

(ETF group) or normal food at will from the first day after major

upper GI surgery. Primary end point was rate of major complications

and death. Secondary outcomes were minor complications and

adverse events, bowel function, and length of stay. All patients were

invited to a follow-up at 8 weeks after discharge from the hospital.

T he literature concludes that patients should be allowed

food without delay (at will) after colorectal surgery and

that the customary withholding of oral intake (nil-by-mouth)

Results: Four hundred fifty-three patients who underwent major for the first postoperative days is unnecessary.1,2 Robust data

open upper GI surgery in 5 centers were enrolled between 2001 and also suggest that we should avoid the nil-by-mouth regimen

2006. Four hundred forty-seven patients were correctly randomized. after major gynecologic,3,4 urologic,5 and vascular surgery.2,6

Of 227 patients 76 (33.5%) had major complications in the ETF In upper gastrointestinal (GI) surgery, however, a strict nil-

group compared with 62 (28.2%) of 220 patients allowed normal by-mouth regimen for several days is widely practiced.7–11

food at will (P ⫽ 0.26, 95% CI for the difference in rate from ⫺3.3 This reluctance to allow food at will is based on the concern

to 13.9). In the ETF group, 36 (15.9%) patients were reoperated for gastric distension and for anastomotic integrity. This

compared with 29 (13.2%) in the group allowed normal food at will concern is not supported by randomized trials.12,13

(P ⫽ 0.50) and 30-day mortality was 10 (4.4%) of 227 and 11 Upper GI surgeons hesitate to allow anything by mouth

postoperatively, and many advocate enteral catheter feeding

postoperatively to a jejunal segment distal to a new anasto-

From the *Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, University Hospital mosis. The safety and feasibility of postoperative enteral

Northern Norway, Tromsø, Norway; †Institute of Clinical Medicine, nutrition by needle-catheter jejunostomies (NCJ) has been

University of Tromsø, Norway; ‡Department of Surgery, Sørlandet

Hospital, Arendal, Norway; §Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, St. extensively documented,14 –18 but serious complications oc-

Olavs Hospital, University Hospital of Trondheim, Norway; ¶Depart- cur.19 Although enteral catheter feeding has been shown to be

ment of Surgery, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway; and beneficial in upper GI surgery patients,20 the preference for

㛳Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Haukeland University Hospital, this modality also rests on the traditional but undocumented

Bergen, Norway.

Supported by the Norwegian Research Council Grant 147339/V50 and

reluctance to allow food at will. These assumed hazards of

Fresenius Kabi AS, Norway. allowing normal food in the immediate postoperative period

Kristoffer Lassen and Arthur Revhaug are members of the Enhanced Re- have not been scientifically tested and should be viewed

covery After Surgery (ERAS) group. From 2006, Fresenius Kabi is a against both the benefits and side effects of any artificial

main sponsor of this group. feeding modality.21

As the corresponding author, Kristoffer Lassen declares that he has had full

access to all the data in the study and accepts final responsibility for the The objective of this trial was to investigate whether the

decision to submit for publication. alleged increase in morbidity associated with allowing food at

Corresponding author: Kristoffer Lassen, MD, PhD, Department of Gastro- will after major upper GI surgery could be sustained in a

intestinal Surgery, University Hospital Northern Norway, Tromso, 9038, randomized trial. We compared a routine of allowing normal

Norway. E-mail: lassen@unn.no.

Copyright © 2008 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

food at will from the first day after surgery with a routine of

ISSN: 0003-4932/08/24705-0721 nil-by-mouth and enteral nutrition for the first 5 postoperative

DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815cca68 days.

Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008 721

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Lassen et al Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008

METHODS mouth postoperatively.16 Patients with severe extra-abdomi-

nal disease or trauma, life expectancy less than 3 months,

Patients and Hospitals short bowel or other undisputed indication for parenteral

The patients were enrolled in 4 tertiary referral centers nutrition were not eligible. Preoperative assessment included

(University Hospitals of Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim, and weight and albumin concentration for stratification by Nutri-

Tromsø) and in 1 secondary referral hospital (Arendal) in tional Risk Index (NRI: 1.519 ⫻ serum albumin level (g/L) ⫹

Norway. The patients were informed verbally and in writing, 0.417 ⫻ (current weight/usual weight) ⫻ 100).22

and written consent was obtained. Adults undergoing both

scheduled and emergency major upper GI surgery and able to Perioperative Care and Interventions

give written informed consent were eligible. The operations Perioperative routines were largely uniform in all par-

were hepatic, pancreatic, esophageal, and gastric resections, ticipating centers. Bowel cleansing was not used, food was

bilioenteric and gastroenteric bypass procedures, and miscel- allowed until midnight before surgery in scheduled cases, and

laneous procedures (eg, ileus with gross small bowel disten- antithrombotic prophylaxis given as low molecular frag-

sion and severe contamination of the upper abdominal cavity mented heparin. Single-dose perioperative antibiotic cover-

after gut perforation) where tradition would indicate nil-by- age was used, and thoracic epidurals were the mainstay of

TABLE 1. Definitions of Complications

Complication Criteria

Major: Infectious/surgical

SIRS Two or more of the following: temperature ⬎38°C, or ⬍36°C, heart rate ⬎90 beats/min, respiratory rate

⬎20/min or PaCO2 ⬍4.3 kPa, white blood count ⬎12,000 cells/mL, ⬍4000 cells/mL or ⬎10% immature

forms.

Bacteremia At least one positive blood culture of pathogenic organisms

Sepsis SIRS ⫹ bacteremia

Pneumonia X-ray confirmed and necessitating antibiotic treatment

Anastomotic leak Necessitating reoperation or demonstrated on autopsy

Bowel obstruction, necrosis, or Necessitating reoperation or demonstrated on autopsy

perforation

Intra-abdominal abscess Necessitating reoperation or percutaneous drainage or demonstrated on autopsy

Intra-abdominal hemorrhage Necessitating reoperation, transfusion of 6 or more units of packed red blood cells within first 48 h p.o., or

demonstrated on autopsy

Wound rupture Necessitating resuturing in general anesthesia or demonstrated on autopsy

Pancreatitis Serum enzyme level twice upper normal value, absence of known preexisting pancreatitis, ERCP, or

mechanical trauma to pancreas during operation providing satisfactory explanation for elevated enzymes

Cholecystitis Confirmed by histological examination of specimen or by cultured content from percutaneous drainage

Major: Other

Myocardial infarction Diagnostic enzyme pattern and either typical pain or ECG changes, or demonstrated on autopsy

Myocardial arrhythmia ECG-confirmed, with hypotension or symptomatic angina, necessitating stabilizing drugs or electroconversion

Cardiac arrest Confirmed by ECG or cardiac rhythm monitoring, and necessitating resuscitation

Acute cardiac failure Confirmed by echocardiography or necessitating pressure agents

Cerebrovascular hemorrhage or New and persistent (⬎48 h) central neurological deficit, and confirmed by CT scan or demonstrated on

cerebrovascular infarction autopsy

Pulmonary embolism Confirmed by unequivocal nuclear isotope scan, echocardiography, pulmonary angiography, spiral-technique

CT scan, or demonstrated on autopsy

Pulmonary insufficiency Necessitating postoperative ventilation support more than 24 h

Minor

Atelectasis X-ray confirmed and necessitating lung physiotherapy

Wound infection Necessitating removal of stitches and topical treatment, antibiotics or surgical debridement

Incisional hernia As judged clinically

Adverse events

Need for parenteral nutrition, or All intravenous or catheter-delivered substances other than clear crystalloids or colloids will be regarded as

therapeutic enteral feeding (reverting nutrients

to enteral feeding after withdrawal)

Recurrent need of ICU treatment Patients taken from the operating theater to either the ICU department or a postoperative surveillance ward,

depending on clinical status and type of operation. After discharged to the bed ward, any readmission to

these wards will be regarded as failure of this parameter

Use of therapeutic decompression tube Any nasogastric tube inserted after the patient has been primarily extubated and transferred to bed ward

ECG indicates electrocardiogram; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; PaCO2, arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; kPa, kilo pascal; SIRS, systemic inflammatory

response syndrome.

722 © 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008 Food at Will After Surgery Does Not Increase Morbidity

perioperative and postoperative analgesia in all hospitals SPSS 14.0 for Windows. Standard approximation to binomi-

throughout the trial. Nasogastric tubes were removed at the nal distribution by 2 analysis or Fisher exact test was used

end of surgery or at the latest on the first postoperative day when appropriate. Continuous variables were compared by

(POD 1) from when mobilization was encouraged. Student t test. Adjustments were by linear or binary logistic,

The patients randomly assigned to be allowed normal or Cox regression as appropriate. Differences were consid-

food at will were allowed to take ordinary hospital food as ered significant at P ⬍ 0.05.

they wanted from the first day after surgery. They were

encouraged to begin the oral intake carefully and adjust Assignment

according to tolerance. The nutritional intake was not mea- Computerized randomization lists were created and the

sured and there were no target values. results were put in sealed opaque envelopes by individuals not

The patients randomly assigned to enteral tube feeding by involved in the trial. The envelopes were stored in a central

needle-catheter jejunostomy (ETF group) had a feeding catheter randomization office in Tromsø, physically removed from wards

(FloCare Jejunocath, 5 Ch., external diameter 1.7 mm; Nutricia and theaters. Randomization was stratified for hospital and for

Norway AS, Oslo, Norway) passed through the abdominal wall high (esophageal and pancreatic resections) or medium risk

via a split cannula at a 45° angle to the skin and along the axis operations and blocked with a fixed but unknown block size.

of a targeted jejunal loop distal to any anastomosis. Another split After informed consent, the patients were randomized intraop-

cannula allowed a 3 cm intramural passage to be created before eratively if surgery fulfilling the criteria had been performed. A

entering the bowel lumen. The jejunal segment was fixed to the phone call was made to the central randomization office imme-

abdominal wall at the insertion site with absorbable sutures over diately before the closing of the abdominal incision, after the

a length of 3 to 6 cm to prevent kinking.17 The patients received intra-abdominal surgical procedure was completed.

isotonic saline by the catheter at 20 mL/h until the morning of Ethics and Consent

POD 1. Nutrition was then commenced (standard Fresubin, 1

The study was approved by the Regional Division of

kcal/mL; Fresenius Kabi AS, Halden, Norway) at 20 mL/h. The

the National Committee for Research Ethics (P-REK V 52/

rate was increased by 20 mL/h each day if tolerated, up to 80

2000) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on August 23, 2005

mL/h. In the event of abdominal pain, severe distension, or

(NCT00134407). It was carried out in accordance with the

vomiting, infusions were reduced or temporarily halted. A max-

imum of 450 mL of water per day was allowed by mouth. At

POD 6, the patients were allowed food at will and enteral

infusion halted.

End Points and Registration

The primary end point was rates of patients with major

complications or death during hospital stay and within 8 weeks.

Complications were predefined in the protocol (Table 1).

Secondary end points were rates of minor complications

and adverse events, gut-recovery indicators (time to bowel

movement and selective use of nasogastric tube), indica-

tors for underfeeding (clinically indicated selective use of

parenteral nutrition and weight loss) and length of stay after

surgery. Blinding of outcome assessors was not attempted.

All patients were invited to a physical follow-up about

8 weeks after discharge to assess trial outcome. Patients

failing to show up had their hospital files examined for

evidence of unscheduled readmissions to other wards and

hence unregistered postdischarge complications. Finally, the

patients lost to follow-up were crosschecked in the Norwe-

gian Central Population Register to exclude unregistered

death within 8 weeks after discharge.

Statistics

We estimated the minimum rate of patients with major

complications in this heterogeneous population at 25%. A

reduction of this by half (to 12.5%) was considered clinically

important. Detecting a difference of this magnitude or greater

at a level of statistical significance of 0.05 and a power of

0.90 with a two-tailed test of proportions required a total of

215 patients in each group. Correcting for the effect of one

interim analysis, a total number of 444 patients was needed.

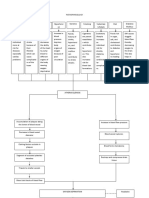

The data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis, with FIGURE 1. Trial flowchart.

© 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 723

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Lassen et al Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008

Helsinki Declaration. An independent interim analysis in RESULTS

2004 confirmed trial continuation to be ethically sound.

Trial enrollment was from February 2001 to April 2006

Role of Funding Source because accrual was slower than expected. Six ineligible

The sponsors did not have any role in the design, data patients were mistakenly randomized and hence excluded. In

collection, analysis or interpretation, writing of the paper, or 3 patients randomized to ETF, catheter insertion was not

in the decision to submit for publication. attempted but they are included in the analysis (trial flow-

TABLE 2. Baseline Comparison of Treatment Groups

Variable Measure Enteral Tube Feeding Allowed Food at Will

Allocated to intervention n 227 220

Treated at university/referral hospital n (%) 202 (89.0) 195 (88.6)

Male proportion % 64.3 53.2

Age (years) Mean (SD) 65 (13.3) 63 (14.4)

Preoperative weight loss (%)* Mean (SD) 4.5 (7.5) 3.4 (6.9)

Preoperative albumine level (g/L)† Mean (SD) 38.7 (5.9) 39.1 (5.3)

Nutritional Risk Index-score‡ Mean (SD) 99.0 (9.5) 99.9 (9.0)

Nutritional status by NRI‡

Not malnourished, NRI: ⬎100 % 49.5 52.4

Borderline malnourished, NRI: 97.5–100 % 12.4 13.4

Mildly malnourished, NRI: 83.5–97.4 % 33.3 29.4

Severely malnourished, NRI: ⬍83.4 % 4.8 4.8

Emergency (not scheduled) operation % 14.1 19.5

*Data available for 193 patients in the Enteral Tube Feeding group and 195 in the Allowed food at will group.

†

Data available for 206 patients in the Enteral Tube Feeding group and 208 in the Allowed food at will group.

‡

Nutritional Risk Index data for calculation available for 186 patients in the Enteral Tube Feeding group, and 187 patients in the Allowed Food

at Will group.

SD indicates standard deviation.

TABLE 3. Operations Performed

Enteral Tube Feeding, Allowed Food at Will, Total,

Operations n (%) n (%) n (%)

Gastrectomy, total 38 (16.7) 39 (17.7) 77 (17.2)

Gastrectomy, subtotal/distal 47 (20.7) 35 (15.9) 82 (18.4)

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple) 47 (20.7) 35 (15.9) 82 (18.4)

Distal pancreatic resection or 3 (1.3) 14 (6.4) 17 (3.8)

pancreaticojejunostomy

Biliodigestive anastomoses 9 (4.0) 9 (4.1) 18 (4.0)

Hepatic resections 25 (11.0) 23 (10.5) 48 (10.1)

Gastroenterostomy 9 (4.0) 5 (2.3) 14 (3.1)

Operation for bowel obstruction with gross 12 (5.3) 26 (11.8) 38 (8.5)

small bowel dilatation

Open redo fundoplications 1 (0.4) 4 (1.8) 5 (1.1)

Transhiatal distal esophagectomies/resections 1 (0.4) 1 (0.5) 2 (0.5)

of the cardia

Transthoracic esophagectomies 4 (1.8) 2 (0.9) 6 (1.3)

Repair of perforated gastric/duodenal ulcers 8 (3.5) 11 (5.0) 19 (4.3)

Operation for bowel perforation/anastomotic leak 10 (4.4) 2 (0.9) 12 (2.7)

Duodenal resection 0 (—) 1 (0.5) 1 (0.2)

Open pancreaticocystogastrostomy 3 (1.3) 1 (0.5) 4 (0.9)

Choledochotomy 1 (0.4) 1 (0.5) 2 (0.5)

Resection of central bile duct 3 (1.3) 2 (0.9) 5 (1.1)

Total pancreatectomy 0 (—) 1 (0.5) 1 (0.2)

Other major, upper abdominal operations or 6 (2.7) 8 (3.6) 14 (3.1)

reoperations

Total 227 220 447

724 © 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008 Food at Will After Surgery Does Not Increase Morbidity

chart: Fig. 1). The groups were comparable by baseline with 100 major complications in the 220 patients allowed

characteristics (Table 2), and by procedures performed normal food at will (P ⫽ 0.012). In the ETF group, 36

(Table 3)—also within each hospital. (15.9%) patients were reoperated compared with 29 (13.2%)

Complications and Adverse Events in the group allowed normal food at will (P ⫽ 0.50) (Table

In the ETF group, 76 (33.5%) of 227 patients suffered 4). Thirty-day mortality was 4.4% in the ETF group and 5.0%

major complications compared with 62 (28.2%) of 220 in the in the group allowed normal food at will (P ⫽ 0.83). Total

group allowed normal food at will (P ⫽ 0.26). When adjusted mortality within the trial period was 8.4% in the ETF

for main baseline variables (gender, age, emergency surgery, group versus 5.9% in the group allowed normal food at

high-risk operations, and operating hospital) there was still no will (P ⫽ 0.36).

significant difference (P ⫽ 0.46). The 227 patients in the ETF Subgroup analysis of the different operations showed

group suffered a total of 165 major complications compared no significant difference in rates of major complications

TABLE 4. Rate of Predefined Complications

Enteral Tube Feeding Allowed Food at will

n ⴝ 227, n (%) n ⴝ 220, n (%) Difference (95% CI) % P

Major, infectious/surgical

SIRS 20 (8.8) 11 (5.0) 3.8 (⫺0.9 to 8.5) 0.14

Bacteremia 6 (2.6) 2 (0.9) 1.7 (⫺0.7 to 4.1) 0.29

Sepsis 12 (5.3) 8 (3.6) 1.7 (⫺2.1 to 5.5) 0.49

Pneumonia 33 (14.5) 26 (11.8) 2.7 (⫺3.6 to 9.0) 0.41

Anastomotic leak 15 (6.6) 10 (4.5) 2.2 (⫺2.1 to 6.5) 0.41

Bowel necrosis 4 (1.8) 2 (0.9) 0.9 (⫺1.2 to 3.0) 0.69

Bowel perforation 1 (0.4) 1 (0.5) ⫺0.1 (⫺1.3 to 1.1) 1.0

Bowel obstruction 6 (2.6) 2 (0.9) 1.7 (⫺0.7 to 4.1) 0.29

Intra-abdominal abscess 16 (7.0) 8 (3.6) 3.4 (⫺0.7 to 7.5) 0.14

Intra-abdominal hemorrhage 8 (3.5) 6 (2.7) 0.8 (⫺2.4 to 4.0) 0.79

Wound rupture 8 (3.5) 6 (2.7) 0.8 (⫺2.4 to 4.0) 0.79

Pancreatitis 1 (0.4) 0 0.4 (⫺0.4 to 1.2) 1.0

Cholecystitis 0 0 — —

Major, other

Myocardial infarction 5 (2.2) 0 2.2 (0.3 to 4.1) 0.06

Myocardial arrhythmia 10 (4.4) 5 (2.3) 2.1 (⫺1.2 to 5.4) 0.29

Cardiac arrest 1 (0.4) 1 (0.5) ⫺0.1 (⫺1.3 to 1.1) 1.0

Acute cardiac failure 5 (2.2) 1 (0.5) 1.7 (⫺0.4 to 3.8) 0.22

Cerebral hemorrhage/infarction 0 1 (0.5) ⫺0.5 (⫺1.4 to 0.4) 0.49

Pulmonary embolism 1 (0.4) 1 (0.5) ⫺0.1 (⫺1.3 to 1.1) 1.0

Pulmonary insufficiency 12 (5.3) 10 (4.5) 0.8 (⫺3.2 to 4.8) 0.83

Patients with major complication 76 (33.5) 62 (28.2) 5.3 (⫺3.3 to 13.9) 0.26

Total number of major complications 165 100 — 0.012

Patients reoperated 36 (15.9) 29 (13.2) 2.7 (⫺3.8 to 9.2) 0.50

Thirty-day mortality 10 (4.4) 11 (5.0) ⫺0.6 (⫺4.5 to 3.3) 0.83

Total mortality within 8 wk (follow-up) 19 (8.4) 13 (5.9) 2.5 (⫺2.3 to 7.3) 0.36

Minor complications and adverse events

Atelectasis 10 (4.4) 11 (5.0) ⫺0.6 (⫺4.5 to 3.3) 0.83

Wound infection 20 (8.8) 11 (5.0) 3.8 (⫺0.9 to 8.5) 0.14

Need for parenteral nutrition 20 (8.8) 25 (11.4) ⫺2.6 (⫺8.2 to 3.0) 0.43

Therapeutic enteral feeding or 6 (2.6) 2 (0.9) 1.7 (⫺0.7 to 4.1) 0.29

reverting to enteral feeding after

transient withdrawal.

Recurrent need of ICU treatment 15 (6.6) 8 (3.6) 3.0 (⫺1.1 to 7.1) 0.20

Use of therapeutic decompression 33 (14.5) 22 (10.0) 4.5 (⫺1.6 to 10.6) 0.15

tube

Patients with any minor complication/ 65 (29.0) 60 (27.3) 1.7 (⫺6.6 to 10.1) 0.75

adverse event

Total number, minor 104 79 — 0.15

complications/adverse events

SIRS indicates systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

© 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 725

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Lassen et al Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008

between groups (data not shown) except for total gastrecto- high-risk operations, and operating hospital) the difference

mies, where 6 (15.8%) of 38 patients in the ETF group had an remained significant (P ⫽ 0.03). The time to first bowel

intra-abdominal abscess compared with none of the 39 pa- movement was not significantly different (mean 4.3 days in

tients in the group allowed normal food at will (P ⫽ 0.012). the ETF group and 4.0 days for those allowed normal food at

Adjusting for the presence or lack of an upper GI anastomosis will, P ⫽ 0.112). The length of stay was longer in the ETF

did not result in any significant differences between treatment group than in the group allowed normal food at will (mean

groups regarding anastomotic leak rate, major infectious 16.7 vs. 13.5 days, P ⫽ 0.046, 95% CI for difference in

complications, or number of patients with any major compli- means from 0.1 to 6.3).

cation.

The rates of minor complications or adverse events Follow-up

were not significantly different (Table 4), nor was the need At follow-up, 40 (19.0%) of 211 patients in the ETF

for parenteral nutrition or selective use of nasogastric tube. group who were discharged alive were found to have suffered

a late complication compared with 24 (11.5%) of 209 in the

Enteral Tube Feeding group allowed normal food at will (P ⫽ 0.04) (Table 6).

Of 224 attempts, 223 NCJ catheters were inserted. Four There were significantly more wound infections in the ETF

patients died within the first 5 postoperative days and another group, 17 of 211 versus 5 of 209 patients in the group allowed

8 patients with functioning catheters requested crossover to normal food at will (P ⫽ 0.01). The patients in the ETF group

food. Thirty-one (13.9%) catheters were prematurely re- had a higher postoperative weight loss (mean 5.2 kg reduc-

moved (Table 5). The remaining 181 patients received a tion in 144 patients) than those in the group allowed normal

median of 4.800 mL enteral feed during the first 5 postoper- food at will (mean 4.0 kg reduction in 152 patients, P ⫽

ative days. Three (1.3%) of 224 patients were reoperated as a 0.06). One of the patients in the ETF group developed a

direct result of catheter complications (two intra-abdominal fistula at the site of the catheter insertion.

leaks and one subcutaneous abscess).

Bowel Function and Recovery DISCUSSION

Time to first flatus was significantly longer in the ETF This randomized trial shows that allowing normal food

group (mean 3.0 days) compared with the group allowed at will immediately after major upper GI surgery does not

normal food at will (2.6 days, P ⫽ 0.01, 95% CI for increase the rate of major complications compared with a

difference in means from ⫺0.7 to ⫺0.2). When adjusted for standard regimen of nil-by-mouth and enteral feeding for 5

main baseline variables (gender, age, emergency surgery, days. Furthermore, both time to resumed bowel function and

postdischarge rate of complications were significantly re-

duced for the group allowed normal food at will.

TABLE 5. NCJ-related Outcome Main Outcome

Enteral Tube Feeding The benefit of allowing normal food at will, as opposed

n ⴝ 227, n (%) to nil-by-mouth, with or without enteral tube feeding, has

Insertion not attempted 3 (1.3) been shown repeatedly for colorectal and major gynecologic

Insertion aborted after difficult 1 (0.4) surgery.1– 4 It does not seem to be dependent either on the

dissection kind or quantity of food taken, and high-caloric sip-feeds

Catheter-related complications Proportion of inserted within the first 5 postoperative days have not been shown to

catheters n ⫽ 223 improve clinical recovery.23 Our aim was to investigate a

Catheter-related infection 3 (1.3) regimen of allowing early food at will in major upper GI

Leakage around insertion site 3 (1.3) surgery as it is practiced in colorectal surgery. The amount of

Intra-abdominal leak verified 2 (0.9) food taken during the first 5 days was not an issue in this trial

Intra-abdominal leak suspected 1 (0.4) as we wanted to investigate the assumed hazards of allowing

Problematic removal 3 (1.3) any food at all, ie, to challenge the tradition of nil-by-mouth.

Other complaints 4 (1.8) Hence, we are not claiming that allowing normal food at will

Total 16 (7.2) confers nutritional benefits in the early postoperative period

Reoperation caused by catheter 3 (1.3) or that selective use of nutritional support is never needed. On

Unscheduled removal (within 31/223 (13.9) the other hand, our results indicate that allowing these pa-

first 5 postoperative days) tients to eat normal food is beneficial and that routine enteral

Clogged 5 feeding by NCJ, although probably providing more calories,

Accidentally pulled or fallen-out 13 is associated with a poorer overall outcome.

Caused by catheter-related 6 Parenteral nutrition support was used selectively in

complaint/complication

both study groups at the discretion of the surgeon based on a

Not caused by catheter 7

clinical judgment of inadequate nutritional intake. The use of

Patient-requested removal 3

parenteral nutrition did not indicate that the group allowed

Removed at reoperation for 3

other reason

food at will was clinically underfed compared with the ETF

Unknown 1

group. Furthermore, we believe that eating food, through the

activation of normal digestive reflexes, has an important

726 © 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008 Food at Will After Surgery Does Not Increase Morbidity

TABLE 6. Outcome at Follow-up

Variable (unit) Measure Enteral Tube Feeding Allowed Food at Will Difference (95% CI) % P

Interval for physical follow-up Median (ICR) 74 (63–91) 71 (63–85) — 0.58

(days postsurgery)

Unscheduled readmittance n (%) 30/211 (14.2) 35/209 (16.7) ⫺2.5 (⫺9.4 to 4.4) 0.45

within 8 wk

Unscheduled reoperation within n 5 3 —

8 wk

Unscheduled re-endoscopy n 2 2 —

within 8 wk

Postdischarge complication (not

predefined)

Abscess n 5 4 —

Pneumonia/sepsis n 5 3 —

Bile-/pancreatic fistula n 1 2 —

Anastomotic leakage n 1 0 —

Anastomotic stricture n 3 1 —

Wound infection n (%) 17 (8.1) 5 (2.4) 5.7 (1.5 to 9.9) 0.01

Incisional hernia n 5 9 —

Cardiovascular (myocardial n 4 1 —

infarction, acute

myocardial insufficiency,

pulmonary embolus,

cerebral infarction, venous

thrombosis)

Other significant n 5 5 —

Total n 46 30 —

Patients with postdischarge n (%) 40/211 (19.0) 24/209 (11.5) 7.5 (0.7 to 14.3) 0.04

complication

Weight loss (follow-up ⫺ Mean ⫺5.2 ⫺4.0 1.3 (⫺2.6 to 0.1) 0.06*

preoperative) kg

*Weight change available for 144 patients in the ETF group, and 152 patients in the Allowed Food at Will group.

ICR indicates interquartile range.

impact on gut recovery, which is central in overall recovery had postdischarge complications and they tended to lose less

after GI surgery.24,25 A multimodal care regimen as used in weight. Length of stay, in an unblinded trial without pre-

this trial (no tubes, thoracic epidural analgesia, avoidance of defined discharge criteria, is a poor outcome parameter and

parenteral opioids, early mobilization, etc) is probably crucial may not reflect recovery. However, alongside the data above,

to exploit the benefits of allowing early food.24,25 In our it might indicate that allowing normal food at will enhances

opinion, the literature somewhat erroneously focuses on the recovery.

different enteral feeding formulas and unjustly disregards the

benefits of eating food as such.

The total number of major complications was signifi- Limitations

cantly lower in the group allowed normal food at will. We Separate analysis of the subgroups in this trial did not

consider such pooling of complications, although widely used reveal any significant increase in morbidity for those allowed

in the medical literature, to be less robust than our primary normal food at will. Although the trial was not powered for

end point: the rate of patients suffering one or more major such stratification, the results of the largest subgroups

complications. We therefore refrain from emphasizing this (Whipple procedures, total and subtotal gastrectomies, and

further. On the other hand, it is important to note that the hepatic resections) accorded with this. Because the group of

catheter-related complications in this trial were similar or operations was heterogeneous, our conclusions may still not

fewer than in most of the recently reported series.14 –16,26 This be automatically valid for each subgroup. Further trials are

indicates that our results are not attributable to errors of needed for each type of surgery to assess the optimal post-

catheter use or technique of insertion. operative practice and there may be subgroups that would

benefit from nasogastric tubes and nil-by-mouth for some

Recovery days. The paucity of esophageal resections in our material

Allowing normal food at will improved recovery of gut reflects the reluctance of the participating surgeons to include

function as indicated by the time to first flatus, which was these patients in the trial. Particular features of these opera-

significantly shorter for those who were allowed to eat. Also, tions might indicate that they should be treated differently

significantly fewer patients in the group allowed normal food from the others.13

© 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 727

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Lassen et al Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008

Approximately 17 percent of the patients were lost to Bjørk and Atle Bernstein (Hospital of Arendal), Jon Sen (now

postdischarge follow-up at 8 weeks. These were evenly East Iceland Regional Hospital, Iceland), Jorunn Sandvik

distributed between the treatment groups, and there were no (now Hospital of Ålesund), and Kristian Storli (now St. Olavs

deaths among them. Major surgical complications would Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital). In addition the

have prompted immediate readmittance to the operating trial- authors thank all the doctors and nurses at the 5 participating

hospital. We cannot exclude the possibility of minor nonsur- centers that made the trial possible by including patients and

gical complications among those lost to follow-up. registering outcomes. Bjørn-Odvar Eriksen, MD, PhD and

Our pretrial estimated rate of major complications was the staff at the Clinical Research Centre, University Hospital

well below that of the trial population. This reduces the risk Northern Norway, Tromsø, provided important assistance in

of type-II error as does our pretrial power set at 0.90. It may methodological discussions, the construction of the database,

be argued that our target reduction (by 50%) is large and that and in pretrial and post-trial statistical calculations. Profes-

a smaller difference may well be clinically important. Clearly, a sors Olle Ljungqvist (Ersta Hospital and Karolinska Institu-

type-II error for a smaller but clinically important difference tet, Stockholm, Sweden), Barthold Vonen (University Hospi-

cannot be excluded. The tendency of our results, however, is tal Northern Norway), and senior consultant Cornelis H.C.

uniform. This might indicate that a nonshowing, smaller differ- Dejong, MD, PhD (University Hospital Maastricht, The

ence would be that of a decrease, not an increase, in major Netherlands) kindly read the manuscript and offered con-

morbidity associated with allowing normal food at will. structive comments. The authors also thank Fresenius Kabi

AS, Norway for providing the enteral nutrition formulas.

Implications and Recommendations

This is the first large randomized trial to challenge the REFERENCES

existing routine of nil-by-mouth in upper GI surgery. Periop- 1. Lewis SJ, Egger M, Sylvester PA, et al. Early enteral feeding versus “nil

erative practice for hepatic and pancreatic surgery and other by mouth” after gastrointestinal surgery: systematic review and meta-

major upper GI procedures may include early removal of the analysis of controlled trials. BMJ. 2001;323:773–776.

nasogastric tube and food at will at some centers, but the 2. Han-Geurts IJ, Jeekel J, Tilanus HW, et al. Randomized clinical trial of

patient-controlled versus fixed regimen feeding after elective abdominal

literature in English is scarce.13 Thus, our results may have surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1578 –1582.

important clinical implications for a large group of patients. 3. Schilder JM, Hurteau JA, Look KY, et al. A prospective controlled trial

We believe that the customary regimen of nil-by-mouth after of early postoperative oral intake following major abdominal gyneco-

major upper GI surgery is unnecessary in most cases. Future logic surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;67:235–240. 关See comments兴.

trials are needed to establish the optimal clinical pathway for 4. Steed HL, Capstick V, Flood C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of

early versus “traditional” postoperative oral intake after major abdomi-

each of the main types of operations reported in this study, nal gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:861– 865.

but we believe that the majority of these patients should be 5. Brodner G, Van Aken H, Hertle L, et al. Multimodal perioperative

allowed normal food at will. There is no evidence that it is management– combining thoracic epidural analgesia, forced mobiliza-

inferior to the current routines, it may enhance recovery, and tion, and oral nutrition–reduces hormonal and metabolic stress and

improves convalescence after major urologic surgery. Anesth Analg.

there is a potential for reducing costs through less expenditure 2001;92:1594 –1600.

on catheters and feeding formulas, and possibly through 6. Mukherjee D. “Fast-track” abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Vasc

shorter lengths of stay. Future trials should focus on the role Endovascular Surg. 2003;37:329 –334.

of nutrition support as an adjunct to food at will, not as an 7. Lassen K, Dejong CH, Ljungqvist O, et al. Nutritional support and oral

alternative. intake after gastric resection in five northern European Countries. Dig

Surg. 2005;22:346 –352.

8. Tanaka M. Gastroparesis after a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenec-

CONCLUSIONS tomy. Surg Today. 2005;35:345–350.

9. Suehiro T, Matsumata T, Shikada Y, et al. Accelerated rehabilitation

This trial has shown that allowing patients to eat normal with early postoperative oral feeding following gastrectomy. Hepato-

food at will from the first day after major upper GI surgery gastroenterology. 2004;51:1852–1855.

does not increase morbidity compared with traditional care 10. Hirao M, Tsujinaka T, Takeno A, et al. Patient-controlled dietary

with nil-by-mouth and enteral feeding. It is the first large schedule improves clinical outcome after gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

World J Surg. 2005;29:853– 857.

randomized trial to challenge the existing routine of nil-by- 11. Atkins BZ, Shah AS, Hutcheson KA, et al. Reducing hospital morbidity

mouth in these patients. and mortality following esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:

1170 –1176.

12. Bisgaard T, Kehlet H. Early oral feeding after elective abdominal

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS surgery–what are the issues? Nutrition. 2002;18:944 –948.

The authors thank the following individuals who par- 13. Lassen K, Revhaug A. Early oral nutrition after major upper gastroin-

ticipated in various phases of the trial: senior consultant Tore testinal surgery: why not? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:

Gauperaa, MD, PhD, implemented the trial in Arendal and 613– 617.

14. Ryan AM, Rowley SP, Healy LA, et al. Post-oesophagectomy early

offered important comments on the manuscript. Implementa- enteral nutrition via a needle catheter jejunostomy: 8-year experience at

tion in the other centers was totally dependent on Professors a specialist unit. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:386 –393.

of Surgery Asgaut Viste (Haukeland University Hospital, 15. Chin KF, Townsend S, Wong W, et al. A prospective cohort study of

Bergen), Jon Arne Søreide (Stavanger University Hospital, feeding needle catheter jejunostomy in an upper gastrointestinal surgical

unit. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:691– 696.

Stavanger); and Helge Myrvold and Jon-Erik Grønbech (St. 16. De Gottardi A, Krahenbuhl L, Farhadi J, et al. Clinical experience of

Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital). For some feeding through a needle catheter jejunostomy after major abdominal

time, trial inclusion locally was done by surgeons Glenn operations. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:1055–1060.

728 © 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

Annals of Surgery • Volume 247, Number 5, May 2008 Food at Will After Surgery Does Not Increase Morbidity

17. Sarr MG. Appropriate use, complications and advantages demonstrated 22. Perioperative total parenteral nutrition in surgical patients. The Veterans

in 500 consecutive needle catheter jejunostomies. Br J Surg. 1999;86: Affairs Total Parenteral Nutrition Cooperative Study Group. N Engl

557–561. J Med 1991;325:525–532. 关see comments兴.

18. Myers JG, Page CP, Stewart RM, et al. Complications of needle catheter 23. MacFie J, Woodcock NP, Palmer MD, et al. Oral dietary supplements in

jejunostomy in 2,022 consecutive applications. Am J Surg. 1995;170: pre- and postoperative surgical patients: a prospective and randomized

547–550. clinical trial. Nutrition. 2000;16:723–728.

19. Han-Geurts IJ, Verhoef C, Tilanus HW. Relaparotomy following com- 24. Kehlet H, Holte K. Review of postoperative ileus. Am J Surg. 2001;

plications of feeding jejunostomy in esophageal surgery. Dig Surg. 182:3S–10S.

2004;21:192–196. 25. Gatt M, Anderson AD, Reddy BS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of

20. Bozzetti F, Braga M, Gianotti L, et al. Postoperative enteral versus multimodal optimization of surgical care in patients undergoing major

parenteral nutrition in malnourished patients with gastrointestinal can- colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1354 –1362.

cer: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1487–1492. 26. Lobo DN, Williams RN, Welch NT, et al. Early postoperative jejunostomy

21. Woodcock N, MacFie J. Optimal nutrition support (and the demise feeding with an immune modulating diet in patients undergoing resectional

of the enteral versus parenteral controversy). Nutrition. 2002;18: surgery for upper gastrointestinal cancer: a prospective, randomized, con-

523–524. trolled, double-blind study. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:716 –726.

© 2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 729

Kaliane Cunha - kalianebcunha@gmail.com - IP: 177.37.205.206

You might also like

- Quiz EmbryologyDocument41 pagesQuiz EmbryologyMedShare90% (67)

- Dr. HY Peds Shelf Parts 1 & 2Document22 pagesDr. HY Peds Shelf Parts 1 & 2Emanuella GomezNo ratings yet

- Basic Care & Comfort Nclex RN UwDocument10 pagesBasic Care & Comfort Nclex RN Uwgwen scribd100% (1)

- Early Oral Intakes After Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy in Esophageal Cancer PatientsDocument9 pagesEarly Oral Intakes After Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy in Esophageal Cancer Patientsaudrey.r.bedwellNo ratings yet

- Post-Oesophagectomy Early Enteral Nutrition Via A Needle Catheter Jejunostomy: 8-Year Experience at A Specialist UnitDocument8 pagesPost-Oesophagectomy Early Enteral Nutrition Via A Needle Catheter Jejunostomy: 8-Year Experience at A Specialist UnitEssoulaymani FirdawsNo ratings yet

- Ne en WhippleDocument9 pagesNe en WhippleOscar VillacresNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 8Document7 pagesContentServer 8Fitra PahlevyNo ratings yet

- JHN 12763Document12 pagesJHN 12763dinosaurio cerritosNo ratings yet

- SURGERY, CURRENT ISSUES IN NUTRITION SUPPORTDocument25 pagesSURGERY, CURRENT ISSUES IN NUTRITION SUPPORTSaadah MohdNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Practical Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryDocument17 pagesESPEN Practical Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryMaríaJoséVegaNo ratings yet

- Timing of Oral Intake After Esophagectomy A Narrative Review ofDocument19 pagesTiming of Oral Intake After Esophagectomy A Narrative Review ofAna RosiNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Transoral Fundoplication Vs Omeprazole For Treatment of Regurgitation in A Randomized Controlled Trial-1Document15 pagesEfficacy of Transoral Fundoplication Vs Omeprazole For Treatment of Regurgitation in A Randomized Controlled Trial-1-Yohanes Firmansyah-No ratings yet

- Vrecenak 2014Document5 pagesVrecenak 2014sigitdwimulyoNo ratings yet

- Feeding The Open Abdomen: Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition September 2007Document7 pagesFeeding The Open Abdomen: Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition September 2007Risda AlwaritsiNo ratings yet

- Clinical NutritionDocument12 pagesClinical NutritionBagus Candra BuanaNo ratings yet

- Cisapride Use in Pediatric Patients With Intestinal Failure and Its Impact On Progression of Enteral NutritionDocument6 pagesCisapride Use in Pediatric Patients With Intestinal Failure and Its Impact On Progression of Enteral Nutritionmango91286No ratings yet

- A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial On The Value of Prophylactic Supplementation Pral NutritionDocument7 pagesA Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial On The Value of Prophylactic Supplementation Pral NutritionOkky IrawanNo ratings yet

- Fast-Track Recovery Programme After Pancreatico-Duodenectomy Reduces Delayed Gastric EmptyingDocument7 pagesFast-Track Recovery Programme After Pancreatico-Duodenectomy Reduces Delayed Gastric EmptyinghoangducnamNo ratings yet

- Penting Banget DibacaDocument15 pagesPenting Banget DibacaDominikus Raditya AtmakaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nutrition: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesClinical Nutrition: Original ArticleBby AdelinaNo ratings yet

- A Myth About Anastomotic LeakDocument3 pagesA Myth About Anastomotic LeakAvinash RoyNo ratings yet

- Early Feeding After Digestive Surgery Is 43f243f3Document4 pagesEarly Feeding After Digestive Surgery Is 43f243f3sarahsamaliaNo ratings yet

- Ebp Presentation 1Document21 pagesEbp Presentation 1api-340248301No ratings yet

- Risk of Failure in Pediatric Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts Placed After Abdominal SurgeryDocument31 pagesRisk of Failure in Pediatric Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts Placed After Abdominal SurgeryWielda VeramitaNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction Is There A PDFDocument3 pagesPattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction Is There A PDFMaría José Díaz RojasNo ratings yet

- Advances in Surgical NutritionDocument11 pagesAdvances in Surgical NutritionOtto Guillermo SontayNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DewiDocument8 pagesJurnal DewiAD MonikaNo ratings yet

- Gastro Graf inDocument12 pagesGastro Graf inquileuteNo ratings yet

- Park 2012Document7 pagesPark 2012Endah Rahayu MulyaniNo ratings yet

- Konstipasi ICUDocument7 pagesKonstipasi ICUHusna LathiifaNo ratings yet

- Chewing Gum PDFDocument5 pagesChewing Gum PDFIndriHariMurtiNo ratings yet

- Can Postoperative Nutrition Be Favourably Maintained by Oral Diet in Patients With Emergency Temporary Ileostomy? A Tertiary Hospital Based StudyDocument5 pagesCan Postoperative Nutrition Be Favourably Maintained by Oral Diet in Patients With Emergency Temporary Ileostomy? A Tertiary Hospital Based StudydwirizqillahNo ratings yet

- Usefulness of Gum Chewing To Decrease Postoperative Ileus in Colorectal Surgery With Primary Anastomosis: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument5 pagesUsefulness of Gum Chewing To Decrease Postoperative Ileus in Colorectal Surgery With Primary Anastomosis: A Randomized Controlled TrialTay LiMinNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Ileus: Cristina R. Harnsberger, MD Justin A. Maykel, MD Karim Alavi, MD, MPHDocument5 pagesPostoperative Ileus: Cristina R. Harnsberger, MD Justin A. Maykel, MD Karim Alavi, MD, MPHfatima chrystelle nuñalNo ratings yet

- Early Feeding in Acute Pancreatitis in Children A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesEarly Feeding in Acute Pancreatitis in Children A Randomized Controlled TrialvalenciaNo ratings yet

- Bar Dram 2000Document6 pagesBar Dram 2000Prasetyö AgungNo ratings yet

- Advances in Surgical NutritionDocument10 pagesAdvances in Surgical NutritionAndyNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Nutritional Support in Cancer Patients With No Clinical Signs of Malnutrition - Prospective Randomized Controlled TrialDocument6 pagesPreoperative Nutritional Support in Cancer Patients With No Clinical Signs of Malnutrition - Prospective Randomized Controlled TrialtttttNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryDocument28 pagesESPEN Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryMicheline Tereza PiresNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryDocument28 pagesESPEN Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryekalospratamaNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: Is There A Change in The Underlying Etiology?Document4 pagesPattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: Is There A Change in The Underlying Etiology?neildamiNo ratings yet

- Superior efficacy of pancreatin 25 000 MMS in PEI after pancreatic surgeryDocument12 pagesSuperior efficacy of pancreatin 25 000 MMS in PEI after pancreatic surgeryNikola StojsicNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic TestsDocument11 pagesDiagnostic TestsMae GabrielNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Fasting: A Time To Relook: Guest EditorialDocument2 pagesPerioperative Fasting: A Time To Relook: Guest EditorialIbraim CervantesNo ratings yet

- Anaemia+in+pregnancy 27042016Document5 pagesAnaemia+in+pregnancy 27042016Alma AwaliyahNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nutrition: Meta-AnalysesDocument13 pagesClinical Nutrition: Meta-AnalysesBby AdelinaNo ratings yet

- @medicinejournal European Journal of Pediatric Surgery January 2020Document126 pages@medicinejournal European Journal of Pediatric Surgery January 2020Ricardo Uzcategui ArreguiNo ratings yet

- Volume 15, Number 3 March 2011Document152 pagesVolume 15, Number 3 March 2011Nicolai BabaliciNo ratings yet

- Gum Chewing SurgeryDocument3 pagesGum Chewing SurgeryTony YuliantoNo ratings yet

- Access and Complications of Enteral Nutrition Support For Critically Ill PatientsDocument17 pagesAccess and Complications of Enteral Nutrition Support For Critically Ill Patientsribka sinurayaNo ratings yet

- Nasal Feeding Tubes Are Associated With Fewer AdveDocument7 pagesNasal Feeding Tubes Are Associated With Fewer AdveuchoaNo ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitisDocument9 pagesAcute PancreatitisJayari Cendana PutraNo ratings yet

- Gastrografin TrialDocument12 pagesGastrografin Trialkelly_ann23No ratings yet

- Incidence of Aspiration and Gastrointestinal Complications in CriticallyillDocument6 pagesIncidence of Aspiration and Gastrointestinal Complications in CriticallyillHernando CastrillónNo ratings yet

- 65 Stenoza GDDDocument7 pages65 Stenoza GDDGabriela MilitaruNo ratings yet

- Post Whipple, Nutrition ManagementDocument9 pagesPost Whipple, Nutrition ManagementHinrich DoradoNo ratings yet

- Enteral Nutrition Therapy For The Surgical PatientDocument52 pagesEnteral Nutrition Therapy For The Surgical PatientelenNo ratings yet

- Ahbps-24-44 Appendicitis After Liver Transplantation JournalDocument8 pagesAhbps-24-44 Appendicitis After Liver Transplantation JournalIndah JamtaniNo ratings yet

- Protocol oDocument8 pagesProtocol oCynthia ChávezNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Pancreatoduodenectomy With or Without Pyloric Preservation: A Clinical Outcomes ComparisonDocument9 pagesResearch Article: Pancreatoduodenectomy With or Without Pyloric Preservation: A Clinical Outcomes ComparisonHiroj BagdeNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryDocument28 pagesESPEN Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryMeliSsa DanielaNo ratings yet

- Top Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyFrom EverandTop Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Nutritional Support after Gastrointestinal SurgeryFrom EverandNutritional Support after Gastrointestinal SurgeryDonato Francesco AltomareNo ratings yet

- Locomotion and Movement-1Document41 pagesLocomotion and Movement-1Satender Yadav100% (1)

- Medical History FormatDocument5 pagesMedical History Formatkrzia TehNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Fetal Growth and DevelopmentDocument12 pagesAssessment of Fetal Growth and Developmentaracelisurat100% (1)

- Body FluidsDocument85 pagesBody FluidsShanta BharNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology Tia VS CvaDocument6 pagesPathophysiology Tia VS CvaRobby Nur Zam ZamNo ratings yet

- Milk Powder Production: by N.ChikuniDocument17 pagesMilk Powder Production: by N.Chikunimatthew matawoNo ratings yet

- MebendazolDocument11 pagesMebendazolDiego SalvatierraNo ratings yet

- Sleep Disorder Risks for Elderly CoupleDocument2 pagesSleep Disorder Risks for Elderly CoupleMushy_ayaNo ratings yet

- Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews-1973-Payne-409.fullDocument44 pagesMicrobiology and Molecular Biology Reviews-1973-Payne-409.fulljvan migvelNo ratings yet

- Class 9 TissueDocument10 pagesClass 9 Tissuekhatridheeraj657No ratings yet

- MTF, Sba-Gmt202: (Ne Osa)Document5 pagesMTF, Sba-Gmt202: (Ne Osa)Zahra HussainNo ratings yet

- Slide 1 Pharmacological Management of Cancer Pain in AdultsDocument64 pagesSlide 1 Pharmacological Management of Cancer Pain in Adultsbagus satriyasaNo ratings yet

- The Resilience Workbook Essential Skills To Recover From Stress, Trauma, and Adversity (Glenn R. Schiraldi) (Z-Library)Document306 pagesThe Resilience Workbook Essential Skills To Recover From Stress, Trauma, and Adversity (Glenn R. Schiraldi) (Z-Library)amazzineayoub100% (2)

- Excretion: Excretion. Elimination of Drugs and Its Metabolites FromDocument18 pagesExcretion: Excretion. Elimination of Drugs and Its Metabolites FromAlphahin 17100% (1)

- Oral MucoceleDocument4 pagesOral MucoceleankitbudhirajaNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Coral Reefs - Status Report 1970-2012 PDFDocument306 pagesCaribbean Coral Reefs - Status Report 1970-2012 PDFbutterflybreNo ratings yet

- Western Mindanao State University College of Nursing: Zamboanga CityDocument11 pagesWestern Mindanao State University College of Nursing: Zamboanga CitySHAINA ALIH. JUMAANINo ratings yet

- Simsek & Duman, 2017 PDFDocument4 pagesSimsek & Duman, 2017 PDFCáceres EmiNo ratings yet

- 6mwt Guidelines Brochure Abs3103Document3 pages6mwt Guidelines Brochure Abs3103ec16043No ratings yet

- India's Oral Healthcare Industry Growing Despite Low PenetrationDocument3 pagesIndia's Oral Healthcare Industry Growing Despite Low PenetrationSaranya KRNo ratings yet

- Multiple MyelomaDocument28 pagesMultiple MyelomaBHAGYASHREE SHELAR100% (2)

- Tracheoesophageal Fistula Surgery OutcomesDocument59 pagesTracheoesophageal Fistula Surgery OutcomesTulasiNo ratings yet

- Patient's Profile Name: S.T. Age: 3y/o SexDocument3 pagesPatient's Profile Name: S.T. Age: 3y/o SexCharles_Guzman_1567No ratings yet

- A Single-Arm Study of Sublobar Resection For Ground-Glass Opacity Dominant Peripheral Lung CancerDocument15 pagesA Single-Arm Study of Sublobar Resection For Ground-Glass Opacity Dominant Peripheral Lung CancerYTM LoongNo ratings yet

- Management of Migraine Headache: An Overview of Current PracticeDocument7 pagesManagement of Migraine Headache: An Overview of Current Practicelili yatiNo ratings yet

- NCM 101 Health AssessmentDocument7 pagesNCM 101 Health AssessmentCristoper Bodiongan100% (1)

- Telehealth and Telemedicine (Reaction Paper)Document2 pagesTelehealth and Telemedicine (Reaction Paper)Thartea RokhumNo ratings yet