Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Debra Nails, The Dramatic Date of Plato's Republic, The Classical Journal, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Apr. - May, 1998), Pp. 383-396

Uploaded by

Valquíria AvelarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Debra Nails, The Dramatic Date of Plato's Republic, The Classical Journal, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Apr. - May, 1998), Pp. 383-396

Uploaded by

Valquíria AvelarCopyright:

Available Formats

The Dramatic Date of Plato's Republic

Author(s): Debra Nails

Source: The Classical Journal, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Apr. - May, 1998), pp. 383-396

Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298163 .

Accessed: 26/08/2013 07:16

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Classical Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE DRAMATICDATE OF PLATO'SREPUBLIC

The scholarly debate that followed Boeckh's 1874 argument

that 411/410 is the dramatic date of Plato's Republic'has led

not to consensus but to a contemporary standstill. Recent

translatorsand commentatorswho are not silent on the issue typi-

cally provide, and with little or no comment, one of two widely

held dramatic dates, Boeckh's 411/410 or the earlier 422/421,2 but

there have been scores of arguments bearing on several suggested

dramatic dates for the Republicranging from 424 to 408.3 Guthrie

declares the date uncertain,4and Moors argues against both dates

that Plato is deliberately producing a "timeless" dialogue.5

1

August Boeckh, GesammelteKleineSchriften(Leipzig 1874) 4.448.

2 For 411/410, cf. Lewis Campbell, Plato's "Republic"(Oxford 1894) 3.2; Paul

Shorey,PlatoTheRepublic(London1930)introduction;BenjaminJowett, TheDialogues

of Plato translatedinto English with Analysesand Introductions(Oxford 1953); Eric

Voegelin, Orderand History (Baton Rouge 1957) 3.53 n. 4; and Allap Bloom, The

Republicof Plato (New York and London 1968) 440 n. 3. For 422/21, cf. D. J. Allan,

Plato RepublicBookI (London 1940) 20; A. E. Taylor, Plato, the Man and his Work

(Cleveland 1956) 264; Desmond Lee, Plato: The Republic(London and New York

1955) 60; Jacob Howland, TheRepublic:TheOdysseyof Philosophy(New York 1993)

xii-who specifies 421/420; and RobinWaterfield,PlatoRepublic(Oxford 1993)380,

with certain reservations. For convenience, I will refer to these dates as 411 and

421 below.

3 At the two extremes, H. D. Rankin, Plato and the Individual(London 1964)

120, supports 424; and Eduard Zeller, Plato and the OlderAcademy(London 1876),

supports 409/408, as does J. Adam, TheRepublicof Plato (Cambridge 1926), who

says "perhaps 409." Kenneth J. Dover, Lysiasand the CorpusLysiacum(Berkeley

1968)4 53, identifies a window of 421-415 on grounds that will be pivotal below.

W. K. C. Guthrie, Plato the Man and His Dialogues(Cambridge 1975) 437-38,

systematically considers dramatic date claims for each of Plato's dialogues. His

word "uncertain,"however, suggests that Plato intended a dramatic date, but that

moderns cannot be sure what it was. I maintain rather that Plato never "edited"

the dialogue from the standpoint of dramatic date at all.

5 Kent Moors, "The Argument Against a Dramatic Date for Plato's Republic,"

Polis 7.1 (1987) 6-31& 22; this amounts to a stronger claim about Plato's literary

technique than that advanced by E. R. Dodds, Plato'sGorgias(Oxford 1959) 17-18,

for the Gorgias(see below). Moors (24 n. 7) cites disputants not included by Guthrie.

For general studies on dramatic order, see Diskin Clay, "Gaps in the Universe' of

the PlatonicDialogues,"BostonAreaColloquium on AncientPhilosophy3 (1987)131-57;

TheClassicalJournal93.4 (1998) 383-96

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

384 DEBRANAILS

One reason for current interest in the dramatic date of the

dialogue is that the well-known "developmental hypothesis" in

the philosophical interpretation of the dialogues has receded in

recent years.6According to this interpretive strategy, the dialogues'

dates of composition are mapped against Plato's evolution from a

mere follower of Socrates to an original philosopher in his own

right: that is, early, middle and late dialogues map the rise and fall

of the theory of forms. So long as this hypothesis held sway, the

supposed order of composition dictated the order in which the

dialogues were read and taught.7 Now, with developmentalism

increasingly under attack,"new and renewed approaches to the

Platonic corpus are emerging. Increased interest in the dialogues

as literature has made the attempt to establish a dramatic date for

the Republicmore urgent,9 particularly because its dramatic date

impinges on those of several other dialogues.10 What makes the

and Charles L. Griswold, "Irony in the Platonic Dialogues," in TheSovereigntyof

Construction:Studiesin the Thoughtof DavidLachterman (Amsterdam 1996).

6 The position has a long history, beginning with Karl Friedrich Hermann,

Geschichteund Systemder PlatonischenPhilosophie(Heidelberg 1839), and strongly

influenced early on by the stylometric work of Lewis Campbell, TheSophistesand

Politicusof Plato (Oxford 1867). It is closely associated nowadays with the writings

of GregoryViastos and those of his many followers.Vlastos'smost complete defense

of the view appears in Socrates:IronistandMoralPhilosopher(Cambridge 1991).

7 Cf. JacobHowland, "Re-readingPlato:The Problemof PlatonicChronology,"

Phoenix45 (1991) 189-214.

8

Directand recentattackshave been made by HolgerThesleff,Studiesin Platonic

Chronology(Helsinki 1982) 8-17, 40-52; and Debra Nails, Agora,Academy,and the

ConductofPhilosophy (Dordrecht1995)53-75--both of which cite numerousprecedents.

Charles Kahn, who remarks in Platoand the SocraticDialogue(Cambridge 1996) on

his having thought innocently in 1991 that the developmental view of the earlier

dialogues "had by then collapsed of its own weight" (xviii), remains remarkably

developmentalist.JohnCooper,PlatoComplete Works(Indianapolis1997),characterizes

the developmental hypothesis charitably but concludes that it is "an unsuitable

basis for bringing anyone to the reading of these works" (xiv).

9 In "The Origins of the Socratic Dialogue," in TheSocraticMovement(Ithaca

1994), Diskin Clay writes, "More than any of the literary Socratics of the fourth

century, Plato took care to provide some of his Socratic dialogues with a signifi-

cant historical setting" (46). Kahn, Plato, ch. 1, echoes the compliment, crediting

Plato with "invent[ing] the conversations of Socrates with the same freedom as

other Socratic authors, but . . more philosophically and more lifelike" (35). The

paucity of extant fragments,much less whole texts, of the several writers of Saicratikoi

logoimakes me reluctant to draw such conclusions myself, and still more reluctant

to infer from them any consequence for reading the Platonic dialogues.

10Implications for the Phaedrusand Symposiumwill be examined below. But

there are others. The Timaeus,for example, has long been viewed as taking place

the day after the Republic,and the Critiasimmediately after that;Guthrie, TheLater

Plato and the Academy(Cambridge 1978) 198, citing precedents, argues that the

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE DRAMATICDATE OF PLATO'SREPUBLIC 385

issue even morecriticalis thatthe two dates most commonly defended

suggest conspicuously dissimilar images of the conversation held

in the Piraeus that summer day, and thus have differentimplications

for how the dialogue as a whole ought to be understood.

If the gathering took place in 421, Socrates (469-399) was forty-

eight, and Plato's brothers as well as the sons of Cephalus were all

in their early to mid twenties; the optimistic springtime Peace of

Nicias was a few months old in a war that had been going on

sporadically for ten years, and which Athens still fully expected to

win. If the date is a decade later, in 411, Socrates was fifty-eight,

and because a different set of historical events and relationships

comes into play, Cephalus's sons were in their mid forties, while

Glaucon and Adeimantus were in their early twenties; more strikingly,

twenty years into the Peloponnesian War, the expedition to Melos,

Alcibiades's betrayal of Athens, and the humiliating Sicilian defeat

had already been suffered, and Athens was living under the Four

Hundred, then the Five Thousand, in the year before the democracy

regained power-a gloomy, violence-torn, and pessimistic time. The

earlier date has stimulated interpretationsthat point to more irony,

more humor, in the dialogue than is found by those whose belief in

411 encourages them to find more allusions to Socrates's death and

a general preoccupation with destruction and corruption.

While a plausible case can be made for each date, as I will

demonstratebelow, there are problemswith each as well. Ultimately,

the strong evidence for two dates is better construed as evidence

that Plato's great dialogue was cobbled together and revised over

decades.

I. INTRODUCTION

The raw material for deciding between the two dates is chiefly

historical and prosopographical. Besides conflicting details from

various sources that will be considered below, two particulars from

the first book of the Republic must fit the date: the peaceful summer

during the Peloponnesian War years in which the conversation

Philebusalso takes place in the wake of the Republic.The dramatic date of the Sym-

posium (416) puts it either soon after, or just before, the Republic,dependent on

whether 421 or 411 is established; the Laches(424-418), and both the HippiasMajor

and HippiasMinor(421-416) are similarly affected. Cf. for Laches,Thesleff, Studies,

93-94; for HippiasMajor (and thus HippiasMinor), Paul Woodruff, Plato Hippias

Major(Indianapolis 1982) introduction.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

386 DEBRANAILS

explicitly takes place (350d), and the new festival honoring the

Thracian goddess Bendis (327a, 354a), with which the Republic

begins; and one item from the second book: a battle at Megara must

have taken place recently (368a).Biographicaldetails that we know

independently-information about Plato's brothers, the family of

Cephalus, Thrasymachus, and Socrates-must fit as well.

Let us begin with a simple enumerationof the kinds of problems

that beset us when we attempt to fix a dramaticdate for the Republic.

First, there are precedents of all sorts in the Platonic corpus: for

exact dramatic dates, for deliberately indeterminate ones, and for

impossible ones. Second, in part because he lacked our current

categories of historical realism and poetic license, Plato's works

are full of anachronisms. Third, it is the characters and events

established in Books I and II-and their incompatibilities-that

most strain efforts to set a dramatic date for the work as a whole.

Fourth, insofar as Book I may have stood as a separate and aporetic

dialogue, and insofar as a proto-Republicmay have been known in

Athens in the 390s, a single dramatic date may recede from our

grasp. The first two points can be treated by way of introduction,

and the third will provide defenses of the two proposed dramatic

dates; aspects of the fourth will then be sketched briefly.

For a familiar example of an exact dramaticdate in the Platonic

corpus, without resorting to the dialogues set in 399: "the occasion

portrayed in Symposiumis Agathon's first theatricalvictory, gained

in Yet there is precedent as well for carefully setting a

416.'"11

dialogue "in no particular year," as Dodds argues is the case for

the Gorgias.It is not that Plato gives no hints about dramatic date

in that dialogue, it is that he gives concrete evidence for at least

seven different dates stretching from 429 to 405.12The dramatic

date of the Lysis is indeterminate in a less radical way. As Guthrie

puts it: "There is nothing to indicate the dramatic date, nor is it

important. At the end (223b), Socrates describes himself as an "old

man," but since he is talking, not very seriously, to two schoolboys

of twelve or thirteen, one cannot attach much weight to this.'13

Finally, there is the baffling Menexenuswith its impossible date.

Guthrie again: "This is the shock. It is Socrates who recites the

11Kenneth J. Dover, "The Date of Plato's Symposium,"Phronesis 10 (1965) 2-20, 2.

12

Dodds, Plato's Gorgias, 17-18.

13 Guthrie, Plato the Man, 135.

14 Guthrie,

Plato the Man, 313. He adds, "It is also unlikely that Aspasia, the

supposed author of the speech, was still alive. She bore a son to Pericles about 440

or earlier." Aspasia, if living, would have been in her late seventies or eighties.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE DRAMATICDATEOF PLATO'SREPUBLIC 387

speech, but the Peace of Antalcidas was concluded twelve or thirteen

years after his death."14 The Republic may have a dramatic date, or

several, or none; precedents cannot help us here.

Anachronisms are a closely related problem. I have just presented

information about the dramatic dates of a few dialogues as if Plato

attended carefully to the notion of dramatic date and controlled it

as skillfully as he did other literary devices. If that assumption is

given free rein, as it sometimes has been,15 interpreters holding a

411 date may gasp and get goose flesh that Plato raises Cephalus

from the dead to play a role in Republic I. Perhaps it is a stroke of

literary genius to have a really dead man speak of dying conven-

tions, but perhaps it is just an anachronism. Republic I includes at

least two anachronisms that are no sparkling literary gems:

Ismenias the Theban is used as an example of a corrupt rich man

(336a) though it was not until after Socrates's death that his iniq-

uities, taking bribes from the Persians, began. And the athlete

Polydamas is hauled in (338c) as someone whose massive physique

requires meat, but his fame for victory in the pancratium occurs

only in 408.16 On the face of it, Plato does not appear to have been

especially concerned with historical accuracy, and that renders

suspect facile claims about his deploying time for literary

purposes. Such manipulation achieves its effect only if there is a

nascent historical realism to play it against. Otherwise it goes

unnoticed.

II. THEEVIDENCE

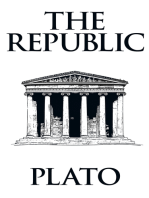

As Figure 1 shows, both dates meet the interval of peace criterion,

albeit very differently: 421 because the Peace of Nicias was in

effect following the Archidamean War; the appearance of Niceratus,

son of Nicias, as a minor character in the Republic may be in honor

of Nicias. But the year 411 also meets the criterion because Athens

was under the rule of the Four Hundred, and then the Five

Thousand-terror, political assassination, and oligarchic revolution,

yes, but no foreign war to draw away Socrates's respondents.17

15Moors, "Argument Against," 23-24 n. 4, argues from Philebus30c that "the

usage of time elements in the dialogues is intentional, as much a part of dialogical

form as setting or characters."

16 Allan, Plato, 20 and 92. In

antiquity, the Babylonian Herodicus, called the

"Cratetean" (secondcenturyB.C.E.),was alsomuchconcernedaboutPlato'sanachronisms;

cf. I. Diiring,HerodicustheCratetean: A Studyin Anti-Platonic

Tradition

(Stockholm1941).

17Thucydides 8.60-109; his narrativebreaks off in the middle of the year.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

388 DEBRANAILS

The inaugural festival of Bendis accommodates 421 marginally

better than it does 411 but it does not accommodate either especially

well. The religion of Bendis may have been known in Athens as

early as 443, though Shorey was persuaded by "inscriptions to prove

its establishment in Attica as early as 429/428."18 Others, Dover

for example, are less sanguine about the value of the inscriptions

since the date itself rests on an emendation.19 It is plausible in any

case that the first formal celebration in the Piraeus was held a few

years later in 421. But it is likewise plausible, as Mommsen held,

that Socrates was referring to special ceremonies introduced in 411 /

410. The depleted Athenian treasuries were in fact filling up again

after so long at war, and religious festivals were early beneficiaries

of the new revenue. So a torch-race on horseback fits both an

inauguration in 421 and a splendid revival resembling an inaugu-

ration around 411. Moors has found in Thucydides a factor that

adjusts the balance in favor of 421:20 Thracians were participants

in the festival, and Bendis was their goddess. Whereas the period

around the Peace of Nicias in 421 was a time of alliances between

Athens and various Thracian cities, by 411 Sparta was pressing

against the Hellespont and Thracian regions, making it less likely

that a contingent of Thracians could afford to leave their homes

vulnerable in summer, the war season.

So far, both dates are possible, and 421 has a slight edge. Let us

now consider evidence based on the ages of the participants, using

precision in the service of clarity, however unwarranted by the

available sources: Socrates was forty-eight in 421 and fifty-eight in

411. At either age he might engage the extremely old Cephalus

(328b) in a discussion of what the last part of the road of life might

hold, and there is not much in his further words or behavior to go

on. One might examine whether his behavior closely resembles that

in any of the dialogues for which a dramatic date is firmer: in the

Protagoras he is about thirty-seven, in the Lachesperhaps forty-five,

in the Symposium, fifty-three, in the Ion sixty-four.21 Despite the

firmer dramatic dates, the tracing of the character Socrates's subtle

18 T. Kock, Comicorum Atticorum Fragmenta (Leipzig 1880) 1.34, and August

Mommsen, Feste der Stadt Athen im Altertum (Leipzig 1898) 490-both cited in

Shorey, Plato, 8, nn. c and f, respectively.

19Dover,

Lysias, 31 n. 3.

20Moors, "Argument Against," 10 and nn. 21-23.

21

Dramatic dates used for this gloss are 432 for the Protagoras, 424 for the

Laches, 416 for the Symposium, and 405 for the Ion-but the literature on even such

"firmer" dates is vast. Cf. note 10 above for Laches and Symposium; for Protagoras,

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE DRAMATICDATE OF PLATO'SREPUBLIC 389

aging across those dialogues, particularly after the Protagoras,is a

speculative matter yielding little if anything of substance. What is

nonetheless important about Socrates's age is its relation to the ages

of the respondents in the Republic,to whom I will now turn.

Since Aristophanes lampoons Thrasymachus of Chalcedon in

427 in the Daiteles, the sophist's reputation was well in place by

either date.22Thrasymachusis assigned aflouritof 430-400, implying

birth around 455, making him some fourteen years or so younger

than Socrates. If the dramatic date is 421, Thrasymachus would be

thirty-four, some ten years older than the rest of the participants;

whereas if the date is 411, he would be forty-four, twenty years

older than Adeimantus and Glaucon, but roughly the same age as

Cephalus's sons, Lysias in particular,whom he may well have been

visiting, perhaps out of their shared interest in rhetoric, for they

are linked not only in the Republic,but in the Phaedrusand Clitophon

as well.23 Clitophon, a minor character in the Republic,may be

assumed to be the same Clitophon as the one linked to

Thrasymachus and Lysias in the dialogue bearing his name. So

Clitophon, Thrasymachus, and Lysias form a sort of unit in the

Republic.24

In the remainder of our consideration of the evidence-which

at this point becomes strikingly more controversial-the ages of

two groups of brothers will be examined: Cephalus's sons,

Polemarchus, Lysias, and Euthydemus; and Ariston's sons,

Adeimantus, Glaucon, and Plato. To establish the facts about the

life of Lysias, we are fortunate to have Dover's careful study. From

the speech of Lysias known as "XII,"the following biographical

data emerge: Pericles persuaded Cephalus to settle in Attica where

he lived for thirty years, dying before the Thirty Tyrants came to

power. Lysias's brother, Polemarchus, was executed by the Thirty

in 404. The remaining contemporary evidence is more difficult to

evaluate, yielding wide open windows rather than exact dates.

Alfred Edward Taylor, Plato:TheManandHis Work(Cleveland 1956) 236, followed

by Guthrie, Plato theMan, 214. The Ion is especially controversial: cf. e.g. W. R. M.

Lamb,PlatoIon(London 1925)introduction,who argues for 405-404; Charles Kahn,

"Did Plato Write Socratic Dialogues," CQ (1981) 31 305-20, argues for internal

contemporary allusions fixing the dramatic date at 394/393, and thus against any

dramatic date, "since Socrates was unavailable" (308 n. 9).

22 H. Diels and W. Kranz,Die Fragmente (7th edn. Berlin 1954)

der Vorsokratiker

fr. A4.

23

Plato, Phaedrus266c, 269d, and 271a;Clitophon406a.

24

Cf. Dover, Lysias,52-53.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

390 DEBRANAILS

Dover accepts very little of the secondary evidence, though Plato's

Phaedrus he finds useful, as we will see.25 From Dionysios of

Halicarnassus, writing in the late first century B.C.E.,Dover allows

only that the family was originally from Syracuse, that Lysias was

born in Athens, and that he was fifteen when he and his brothers

went to the Athenian colony at Thurii.26To allow Dionysios's more

precise claims that Cephalus's sons settled in the colony when it

was founded in 443, or that Lysias returned to Athens in 412/411,

would have had the effect of rendering any dramatic date for the

Phaedrusimpossible since Phaedrus himself was in exile 415-404.

Dionysios's evidence yields a dramatic date of 411 for the Republic,

when Lysias would have been about forty-seven (and his brothers,

perhaps, in their mid forties to early fifties). As I mentioned, that

would make Lysias a rough age-mate of Thrasymachus.Sifting bits

of later evidence, Dover ultimately suggests that Cephalus settled

in Athens after Pericles had become prominent, about 450-445,

Lysias was born about 445, went to Thurii about 430, returned in

the late 20s, and Cephalus died 420-415. For Dover, 421-415 thus

becomes the range for the dramatic date of the Republic.27By this

calculation, Lysias (and his brothers, presumably) are in their mid

twenties at the time of the action in the Republic,that is, roughly

the ages of Glaucon and Adeimantus.

The beginning of Book II provides new dramatic date issues.

As Dover puts the problem: "Plato's brothers, Glaukon and

Adeimantos, are old enough to have distinguished themselves in

"the battle at Megara," but Glaukon, at least, was not too old at

that time to have had a "lover" who composed elegiacs in his

honour (368a)."28So when was the battle? A. E. Taylor, preferring

a dramaticdate of 421, uses Thucydides'sbattle date of 424,29whereas

Shorey, preferring 411, uses Diodorus Siculus's 409-despite the

25 Dover uses evidence from the Republicto establish a prosopography for

Lysias; I omit precisely that evidence below because it would make a very small

circle of my argument. When Dover (Lysias, 32-33, 41-42 & 43) considers the

Phaedrus,while conceding that Plato may not have had a dramatic date or histori-

cal situation in mind, he goes on to argue from better known data about Isocrates's

life that the Phaedrusputs the birth of Lysias "somewhat earlier than 440." When

he reaches conclusions about Lysias's life, he assigns a dramatic date of 418-416 to

the Phaedrus-right between the two candidate Republicdates.

26 Dionysios, Livesof the TenOrators1.8.2-17.

27Although he says "420-415"(Lysias,42) when assigning a plausible dramatic

date, he later says "421-415"(53) without further comment.

28 Dover, Lysias, 31.

29 Thucydides 4.72.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THEDRAMATIC

DATEOFPLATO'SREPUBLIC 391

anachronism.30 Dover, reluctant to turn Plato into a historian,

points out that there were several candidate battles, even limiting

the search to ones mentioned by actual historians, but that the par-

ticular battle need not have been one that made the record books

anyway.31 The Thucydidean date of 424, imagining Glaucon then

about eighteen, would make Glaucon twenty-one at the time of the

Republic,and Adeimantus older than that.32That would cause a

gap of at least fifteen years between the six-year-old Plato and his

older brother Glaucon, more than that for Adeimantus.33 Such a

gap, while not physiologically impossible, has concerned some au-

thors enough that they have postulated that these men were ac-

tually Plato's uncles.34And Moors has argued that Glaucon was in

fact a youngerbrother of Plato on two grounds.35First, Moors sees

"similarities in characterand dialogical structure"between the Re-

publicand the Symposiumthat lead him to conclude that the Glaucon

of the two dialogues is the same person. Second, Xenophon reports

that when Glaucon was less than twenty, he made himself a laugh-

ing-stock by trying to gain political power, and that Socrates took

him under his wing as a favor to Plato and Charmides,implying that

Glaucon must have been Plato's younger brother.36

The conversation to be recited in the Symposiumtook place when

Apollodorus and Glaucon were very young, long ago.37 But the

date is firmly established as 416, so Moors suggests that Glaucon

was born in 420 or later, making him younger than Plato, vindicating

Xenophon, and utterly precluding any sort of participation by

Glaucon in the Republic,no matterwhat its dramaticdate. That suits

Moors because he believes Plato took extraordinarysteps to prevent

the Republicfrom being assigned any dramatic date, and this is one

of those steps. While evidence is not conclusive for any particular

dramatic date, the Glaucon argument will not work. Not only, as

Moors concedes, is Xenophon untrustworthy in some matters of

30Diodorus Siculus, 13.65.

31

Dover, Lysias, 31.

32Assumed from

Apology34a.

33Plato notoriously says at the end of RepublicVII (540e-541a) that those over

the age of ten are beyond the reach of the guardian-teachers and must be sent out

of the polis. If the dramatic date of the dialogue is 421, Plato-born in 427--can

stay, but if the dramatic date is 411, it is too late for Plato.

34Cf. references in Shorey, Plato, 144-45 n. e.

35

Moors, "Argument Against," 13-16.

36Xenophon, Memorabilia,3.6.

37Plato, Symposium173a.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

392 DEBRANAILS

detail, there is a problem with the text as well. Moors says Socrates

does Plato a "favor," implying that the favor had been requested;

but it seems rather that Socrates checked Glaucon out of feeling for

(EiSvou;) Charmides and Plato-an interpretation independent of

hierarchies of age.38

Moors may still be right that the Glaucon of the Republic and

the Symposium are the same, but he probably goes too far when he

gives 420 or later as Glaucon's date of birth. Glaucon and

Apollodorus were "children" (noaid8v 6wvro v iliov E?zr,173a) in 416,

but they need not have been toddlers. To give Moors his due, since

the framing conversation occurs in about 400,39 making Glaucon

forty-two according to those who favor 421, sixteen years earlier

he would have been twenty-six, and that is not a child, so some

other calculation is indeed necessary if coherence is to be achieved.

If one were to substitute the dramatic date of 411 and postulate an

unrecorded Megarian battle the previous summer, Glaucon could

have been fourteen. Or one might use Diodorus Siculus's already-

anachronistic battle date of 409 to make Glaucon twelve or even

ten (not eleven, because then he would be Plato's twin), assuring

that he would fit the dramatic date of the Symposium. But the

consequence of such a maneuver may not please: the upshot is

either that the Symposium's Glaucon is not Plato's brother, or that

the dramatic dates of the Symposium and the Republic are utterly

incompatible.

III. THE REMAINING UNCERTAINTY

I have mentioned only the most formidable problems of assigning

a dramatic date to the Republic, and I have streamlined-though I

hope I have not oversimplified-even those. The dialogue is neither

internally consistent, nor consistent with other dialogues thought

to have been written in the same period,40 nor consistent with the

historical record (such as it is). It does not help to fall back on Moors'

38

50KpETg 8E,)VOuh (6votT 5iatdtrEXapgiinrivrv rakIa1vo ia8th FHdXtr(ovQ

l

06voq E.C.Marchant,Xenophon

i~not7oEv. Memorabilia (London1923),translatesthe

passage,"forthe sakeof Platoand ... Charmides."

39W.R.M.Lamb,PlatoSymposium (London1925)78.

40Althoughthereis controversy overtheorderof compositionof thedialogues,

GerardR. Ledger,Re-Counting Plato:A Computer Analysisof Plato'sStyle(Oxford

1989)esp. 224-25,uses a wide varietyof contemporary statisticaltechniquesand

farsurpasseshis predecessorsin establishingan orderfor segmentsin whichone

mighthaveconfidence.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THEDRAMATIC

DATEOFPLATO'S

REPUBLIC 393

claim, "Only the philosopher, it seems, can truly understand time,

and thereby make a proper judgment on the propriety of the anach-

ronism," because there are just too many anachronisms.41

I earlier raised the issue of whether the Republicwas originally

conceived as an aesthetic unity, or whether it may have had more

than one origin, thus accounting for its lack of a univocal dramatic

date. There are several arguments that raise doubt that the Republic

was written all at once. The least controversial is that Book I stood

as a separate dialogue, an idea with us since 1839 that seems to

have gained some acceptance.42While there are still disputes over

whether Book I as it currently exists is the original Book I, or

whether it was rewritten into its present form; and while there are

disputes about the dating of Book I as a separate dialogue,

stylometric evidence argues for its similarity to other Socratic or

elenctic dialogues.43 But there is a good deal more diversity to be

accounted for in the Republic.Else has argued that a considerable

portion of Book X, though not the myth of Er, was an addition to

the dialogue.44And, apart from the so-called early style of Book I,

there is cramped late style in parts of the dialogue as well, by which

I mean passages that resemblethe distinctive prose of such dialogues

as the Sophist, Timaeusand Laws.45Thesleff has identified several

41Moors,

"ArgumentAgainst," 24 n. 4.

42Cf. Hermann, Geschichte.Thesleff, Studies, 107-110 esp. n. 19, details and

provides referencesfor seven succinctargumentsthat Book I was originallyseparate.

Vlastos, Socrates:Ironist, 46-47, also takes Book I to have been separate, and is

followed by RichardKraut,ed., who separates the composition of Book I from that

of the remainderof the dialogue in the prefatorymaterialof the Cambridge Companion

to Plato (Cambridge 1992) without comment as if the issue were no longer

controversial. Charles Kahn mounts a defense of the opposing side in "Proleptic

Composition in the Republic,or Why Book I Was Never a Separate Dialogue," CQ

ns 43 (1993) 131-42.

43Leonard Brandwood, TheChronologyof Plato's Dialogues(Cambridge 1990)

251, citing Hermann Siebeck, Untersuchungenzur PhilosophiederGriechen(Freiburg

1888), Constantin Ritter, UntersuchungeniiberPlaton (Stuttgart 1888), and H. von

Arnim, De Platonis Dialogis Quaestiones Chronologicae(Rostock 1896). Kahn,

"Proleptic," counters that, in his view, stylometry demonstrates only that Book I

was written earlierthan the other books, but "cannotpossibly show howmuchearlier

it was written" (134, his emphasis); Kahn thinks "scholars like Wilamowitz and

Friedlander were simply taken in" (133) by von Arnim, who himself was "self-

deceived" (134).

44 G. F. Else, "The Structure and Date of Book 10 of Plato's Republic,"

Abhandlungen derHeidelberger AkademiederWissenschaften, Philosophisch-historische

Klasse 3 (1972).

45 None of this material is touched by Kahn, "Proleptic"-nor can it be. His

proposal of prolepsis is a hypothesis about composition, but it fails as a hypothesis

about style.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

394 DEBRANAILS

late-style passages in Books II-V and VII, very likely indicating

late revision of the Republic.46Thesleff has suggested, however, that

when Plato became old enough to require the modern prosthetics

now taken for granted (eyeglasses, hearing aid), an assistant

(dvaypacpe~;), possibly Philip of Opus, is likely to have helped in

the writing of the dialogues we now call "late." If so, alas, we see

the secretary's hand in those late-style passages of the Republic.47

Finally and most controversially, efforts to date not only the

composition of the Republicbut its dramatic date as well will be

altogether feckless if there was in fact a proto-Republic;not Book I,

and not a sketch of the whole, but a subsection of the dialogue that

was known in Athens before 392, and which corresponds roughly

to the late-style passages in Books II-V and VIIthat I just mentioned.

And if the result is what it appears to be, i.e. the very late editing of

a very early segment, it is a perfectexample of what cons a computer

engaged in stylometric studies into a label of "middle": the two

extremes cancel one another out.48While this is not the place to

rehearse the numerous arguments for the existence of a proto-

Republic,49 I would be remissnot to name a few of the more persuasive

among them: (a) there are provocative parallels between Republic

V and Aristophanes'Ecclesiazusae in ideology, action,and language-

yet the play was produced 392, long before the date normally

in

assigned for the writing of the dialogue;50 (b Aulus Gellius writes

that a "two-roll"Republiccame to light initially;51(c) Timaeusexplicitly

46 Thesleff, Studies,137.If he is right about the original boundaries of the proto-

Republic,beginning at 369b, then the biographically problematic passages about

Plato's brothers, like the notorious, appended end of Book I (from 353e), would

seem to have been written to fasten the two previously independent works into one.

47

Thesleff, Studies, 186.

48Ledger, Re-Counting,93.

49 There are many, beginning with Hermann, Geschichte. Cf. J. Hirmer,

"Entstehungund Komposition der Platonischen Politeia," Jahrbiicherfiir Classische

Philologie,Supplementband23 (1897)579-678, esp. 592-98;Thesleff,Studies,102-110,

and his "Platonic Chronology," Phronesis34.1 (1989) 1-26; and Nails, Agora, 116-

22. Kahn, "Proleptic,"131, having introduced what he calls the "separatistpropos-

als" of several early scholars,dismisses their proposals as having "largelycollapsed

under their own weight," but he does not address the contemporaryarguments of

Thesleff,Studies,which he notes only as a "revival"of the earlierenterprise(131 n. 5).

50 Gilbert Murray, Aristophanes(Oxford 1933) 186-89. Thesleff's discussion,

Studies, 103-105, includes extensive citations from the literature. Remarking on

linguistic parallels are two of the play's translators: Douglass Parker,

[Aristophanes's] TheCongresswomen (Ann Arbor 1969) 90 n. 43; and B. B. Rogers,

Aristophanes Ecclesiazusae (London 1924) introduction.

51 Aulus Gellius, NoctesAtticae,14.3.3.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE DRAMATIC DATE OF PLATO'S REPUBLIC 395

purports to summarize the wholeof the preceding day's discussion

rEpiioXtlrEia;,but in fact summarizes only parts of the argument

of RepublicII, III, and V.52

If the Republicsprang whole from the head of Plato, no univocal

dramatic date would thereby be entailed, but the expectation would

gain rather in credibility. If not, if Plato wrote a proto-Republic

before the Academy was established, then its existence militates

against the possibility of determining a single dramatic date for

the dialogue. And if the Republicwas stitchedtogetherfrom a separate

Book I, a proto-Republic,and new material, and revised late into an

almost seamless whole,53 then a single firm dramatic date seems

ever more implausible.54

DEBRANAILS

Mary Washington College

52Plato, Timaeus17b-19b. F. M. Cornford,Plato'sCosmology(Indianapolis 1975)

4-5, argues that Socrates may have described his ideal state more than once, and

that the partial summary that twice calls itself complete is thus not a summary of

the Republicbut of another conversation. Clay, "Gaps,"143-46, argues to the same

end, noting that the sets of characters in the two dialogues are different. Were it

not for the presence and density of other arguments, I would find their explanation

adequate.

53 Diogenes Laertius (3.37) mentions the claim of earlier commentators,

Euphorion and Penaetius, that the beginning of the Republicwas found after Plato's

death in a variety of versions.

54Thispaperdevelops ideas originallypresentedat the HunterCollegeconference

on "The Uses of the Republic"in 1993. It is a pleasure to recall the long and spirited

conversations with Holger Thesleff in the days before the conference that height-

ened my awareness of the complexity of the issues I was raising. I am also grateful

to David Ambuel, WilliamLevitan,JerryPress,and TheClassicalJournal'sanonymous

referee for their comments and helpful insights.

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

396 DEBRANAILS

FIGURE1

SIGNIFICANTEVENTS -458- b. Lysias SIGNIFICANT

EVENTS

FORA 421 DATE -457- FORA 411 DATE

-456-

-455-

-454-

-453-

-452-

-451-

Cephalus settles in Athens -450-

-449-

-448-

-447-

-446-

b. Lysias -445-

-444-

Thurii founded -443- Lysias to Thurii Thurii founded

b. Glaucon -442-

-441-

-440-

-439-

-438-

-437-

-436-

-435-

-434-

-433-

-432-

Peloponn. War, Archidamean War -431- Peloponnesian War

I Lysias to Thurii -430-b. Glaucon

religion of Bendis? -429-

-428-

Aristophanes' Daitqles b. Plato -427- b. Plato Aristophanes' Daiteles

-426-

-425-

Megarabattle (Thucydides) -424-

-423-

Lysias(23) returns -422-

Peace of Nicias -421-

tCep alus -420-

-419-

-418-

-411-

-416-Agathon's victory, Melos expedition

-415- Phaedrus exiled (returns 404)

-414- Alcibiades joins Spartans

-413- Sicilian defeat

-412- Lysias (46) returns

Spartans in Thrace -411- the 400, then the 5,000

-410- "democracy,"festivals renewed

-409- Megarabattle (Diodorus)

-408- pancratiumvictory of Polydamus

This content downloaded from 192.236.36.29 on Mon, 26 Aug 2013 07:16:01 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Dramatic Date of Plato S RepublicDocument15 pagesThe Dramatic Date of Plato S RepublicJavier Arturo Velázquez GalvánNo ratings yet

- Plato's Philosophers: The Coherence of the DialoguesFrom EverandPlato's Philosophers: The Coherence of the DialoguesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Did Plato Coin RhêtorikêDocument16 pagesDid Plato Coin RhêtorikêMohammad AhmadiNo ratings yet

- The Trial and Death of Socrates (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Four DialoguesFrom EverandThe Trial and Death of Socrates (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Four DialoguesNo ratings yet

- Did Plato Write Socratic DialoguesDocument17 pagesDid Plato Write Socratic DialoguesRod RigoNo ratings yet

- Wittgenstein, Plato, and The Historical SocratesDocument42 pagesWittgenstein, Plato, and The Historical SocratesAngela Marcela López RendónNo ratings yet

- Staging - Platos - Symposium SiderDocument22 pagesStaging - Platos - Symposium SiderlicenciaturafilosofiaunilaNo ratings yet

- Plato, Aristotle and SocratesDocument69 pagesPlato, Aristotle and SocratesDan Sima75% (4)

- Republica PDFDocument566 pagesRepublica PDFMouhamed AnisiaNo ratings yet

- 【柏拉图】Leob版理想国第1 5卷Document566 pages【柏拉图】Leob版理想国第1 5卷teetotaler44No ratings yet

- Gorgias & Rhetoric - Joe Sachs TranslatorDocument368 pagesGorgias & Rhetoric - Joe Sachs TranslatorAlfonso Flórez100% (1)

- Socrates: This Article Is About The Classical Greek Philosopher. For Other Uses of Socrates, SeeDocument57 pagesSocrates: This Article Is About The Classical Greek Philosopher. For Other Uses of Socrates, SeeJamie Jampots HapaNo ratings yet

- PHILIP A. STADTER - Pericles Among The IntellectualsDocument15 pagesPHILIP A. STADTER - Pericles Among The IntellectualsM MNo ratings yet

- Represent Things. Right: Too To StateDocument3 pagesRepresent Things. Right: Too To StateAbdul Sami Abdul LatifNo ratings yet

- What Was Socrates CalledDocument13 pagesWhat Was Socrates CalledAngela Marcela López RendónNo ratings yet

- jstor - ethics of soc, 1925Document28 pagesjstor - ethics of soc, 1925Milica MarjanovićNo ratings yet

- Noble Lies &justice On Reading Plato 1973Document28 pagesNoble Lies &justice On Reading Plato 1973hongfengareteNo ratings yet

- Holger Thesleff - Platonic ChronologyDocument27 pagesHolger Thesleff - Platonic ChronologyM MNo ratings yet

- Grotes Plato PDFDocument30 pagesGrotes Plato PDFLuis MartinezNo ratings yet

- Democritus On Politics and The Care of The SoulDocument26 pagesDemocritus On Politics and The Care of The SoulJess Lai-tusNo ratings yet

- 'A Cock For Asclepius' - G. W. MostDocument17 pages'A Cock For Asclepius' - G. W. MostTheaethetus100% (1)

- Protagoras The Atheist - Gabor BolonyaiDocument23 pagesProtagoras The Atheist - Gabor BolonyaiStadec Seminário TeológicoNo ratings yet

- Plato NeoplatonismDocument34 pagesPlato NeoplatonismIvo IvoNo ratings yet

- Phronesis Volume 16 Issue 1 1971 (Doi 10.2307/4181854) B. Darrell Jackson - The Prayers of SocratesDocument25 pagesPhronesis Volume 16 Issue 1 1971 (Doi 10.2307/4181854) B. Darrell Jackson - The Prayers of SocratesNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Plato and SocratesDocument7 pagesPlato and SocratesNiel S. DefensorNo ratings yet

- Leo Strauss - On Plato S SymposiumDocument261 pagesLeo Strauss - On Plato S SymposiumUrko Ibeas100% (1)

- Socrates, or Invoking The Oracle As A WitnessDocument26 pagesSocrates, or Invoking The Oracle As A WitnessAnna LongoNo ratings yet

- Plato and Democracy by S. LangeDocument8 pagesPlato and Democracy by S. LangeGospelNo ratings yet

- Fowler Mythos and LogosDocument23 pagesFowler Mythos and LogosVictor Augusto100% (1)

- Plato's Republic ExplainedDocument509 pagesPlato's Republic ExplainedRemus ĠagaNo ratings yet

- Plato of Athens - Robin WaterfieldDocument253 pagesPlato of Athens - Robin WaterfieldNatan RWNo ratings yet

- Guthrie W K C History Greek Philosophy Volume 3 Part 2 Socrates Fifth Century EnlightenmentDocument205 pagesGuthrie W K C History Greek Philosophy Volume 3 Part 2 Socrates Fifth Century EnlightenmentTorpstrup100% (5)

- A 604578400 PlatuoftDocument628 pagesA 604578400 PlatuoftBranko NikolicNo ratings yet

- Plato - The RepublicDocument508 pagesPlato - The RepublicfmaurorNo ratings yet

- Plato The RepublicDocument508 pagesPlato The Republicdillon_4021848No ratings yet

- Plato - The RepublicDocument508 pagesPlato - The Republichengchao919No ratings yet

- The American Journal of Philology Vol. 100, No. 4 (Winter, 1979), Pp. 497-514Document19 pagesThe American Journal of Philology Vol. 100, No. 4 (Winter, 1979), Pp. 497-514MartaNo ratings yet

- Tarrant Midwifery 1988Document8 pagesTarrant Midwifery 1988Αλέξανδρος ΣταύρουNo ratings yet

- Plato - The RepublicDocument569 pagesPlato - The RepublicGesana BitiNo ratings yet

- Plato's "The RepublicDocument569 pagesPlato's "The RepublicVidi pinemNo ratings yet

- Feedbooks Book 4104 PDFDocument569 pagesFeedbooks Book 4104 PDFVidi pinemNo ratings yet

- Plato - The RepublicDocument569 pagesPlato - The RepublicstregattobrujaNo ratings yet

- Plato - The RepublicDocument573 pagesPlato - The RepublicСукновић ИванNo ratings yet

- Plato - The RepublicDocument508 pagesPlato - The RepublicPacharapol LikasitwatanakulNo ratings yet

- Plato - The RepublicDocument508 pagesPlato - The RepublicPacharapol LikasitwatanakulNo ratings yet

- Review DorionDocument10 pagesReview DorionemcostaNo ratings yet

- Plato: Navigation SearchDocument33 pagesPlato: Navigation SearchhappyminiNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Socrates PDFDocument28 pagesThe Ethics of Socrates PDFShania ShenalNo ratings yet

- Atlantis, L ' Antiquité Classique Author (S) Slobodan Dušanić, Unknown, 2014Document29 pagesAtlantis, L ' Antiquité Classique Author (S) Slobodan Dušanić, Unknown, 2014Dan SimaNo ratings yet

- Pericles' Intellectual Circle ExploredDocument15 pagesPericles' Intellectual Circle ExploredΑλέξανδρος ΣταύρουNo ratings yet

- Plato's Symposium - A Reader's Guide - Cooksey PDFDocument181 pagesPlato's Symposium - A Reader's Guide - Cooksey PDFJonathan TriviñoNo ratings yet

- The Republic of PlatoDocument412 pagesThe Republic of PlatoWaterwind100% (3)

- Composición Del Teseo y Rómulo de PlutarcoDocument16 pagesComposición Del Teseo y Rómulo de PlutarcoFrancisco CriadoNo ratings yet

- MagnesiaDocument448 pagesMagnesiajuliointactaNo ratings yet

- Chance Plato's EuthydemusDocument262 pagesChance Plato's EuthydemusvarnamalaNo ratings yet

- SocratesDocument15 pagesSocratesVishal SawhneyNo ratings yet

- Haileyannotatedbib 1Document4 pagesHaileyannotatedbib 1api-196480787No ratings yet

- The Boy at The Back of The Class-Chapter - 2 QuestionsDocument2 pagesThe Boy at The Back of The Class-Chapter - 2 QuestionsmariannenaNo ratings yet

- Little Red Riding HoodDocument6 pagesLittle Red Riding HoodRailda SantosNo ratings yet

- The Role of Historical Cultural Memory in Uzbek Documentary CinemaDocument5 pagesThe Role of Historical Cultural Memory in Uzbek Documentary CinemaResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Previews Text File 09-2010Document126 pagesPreviews Text File 09-2010usernameNo ratings yet

- AnalogiesDocument12 pagesAnalogiesAamir HussainNo ratings yet

- Odia Sec 2024-25Document6 pagesOdia Sec 2024-25pravatakumars629No ratings yet

- Poems by The Most Eminent LadiesDocument16 pagesPoems by The Most Eminent LadiesRupertoNo ratings yet

- 08 Tintin and The King Ottokars SceptreDocument63 pages08 Tintin and The King Ottokars SceptreSuthinee Owatcharoonroge100% (5)

- The Cambridge Companion To Opera StudiesDocument6 pagesThe Cambridge Companion To Opera StudiesJilly CookeNo ratings yet

- Stylistic Analysis of Psalm 6Document15 pagesStylistic Analysis of Psalm 6Diadame TañesaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Metaphysics of Sanskrit Language: National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, OdishaDocument5 pagesIntroduction To The Metaphysics of Sanskrit Language: National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, OdishaDrSurabhi VermaNo ratings yet

- Preview Ateendriya Rahasyaalu Blavatsky 56369Document12 pagesPreview Ateendriya Rahasyaalu Blavatsky 56369Raj Kumar GundlaNo ratings yet

- The Pre Spanish PeriodDocument8 pagesThe Pre Spanish Periodberdeinatix90% (10)

- De On Tuan 2Document18 pagesDe On Tuan 2Huyền PhạmNo ratings yet

- 129-Article Text-416-4-10-20210803Document7 pages129-Article Text-416-4-10-20210803dg7419648No ratings yet

- Keywordio Longtail KeywordsDocument3 pagesKeywordio Longtail KeywordsDipak Chauhan100% (1)

- The Architectural Technologists Book (Atb) 2015-02Document35 pagesThe Architectural Technologists Book (Atb) 2015-02Lera DenisovaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance Canadian 7th Edition Ross Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesCorporate Finance Canadian 7th Edition Ross Solutions Manual 1rhondamoralesfjmdiwbxkz100% (22)

- Curse of The Crimson Throne - Map FolioDocument17 pagesCurse of The Crimson Throne - Map FolioboNo ratings yet

- Notes Grammar-Phrasal VerbsDocument3 pagesNotes Grammar-Phrasal VerbsMeRy RaHiouiNo ratings yet

- Viola Method Cavallini Book 1Document45 pagesViola Method Cavallini Book 1Roberto TorresNo ratings yet

- Student Weekly Plan: "Spirit Walking in The Tundra" "Spirit Walking in The Tundra"Document15 pagesStudent Weekly Plan: "Spirit Walking in The Tundra" "Spirit Walking in The Tundra"Miss MehwishNo ratings yet

- Alexandre Dumas (Document15 pagesAlexandre Dumas (alexNo ratings yet

- S. Radhakrishnan, J.H. Muirhead (Editors) - Contemporary Indian Philosophy (The Muirhead Library of Philosophy) - George Allen & Unwin (1952)Document654 pagesS. Radhakrishnan, J.H. Muirhead (Editors) - Contemporary Indian Philosophy (The Muirhead Library of Philosophy) - George Allen & Unwin (1952)Frizzy BaoNo ratings yet

- TOGI Research and Referencing Guide 2021Document20 pagesTOGI Research and Referencing Guide 2021Claire DibdenNo ratings yet

- Concise Guide To Information Literacy 2nd Edition 2nd Edition Ebook PDFDocument52 pagesConcise Guide To Information Literacy 2nd Edition 2nd Edition Ebook PDFjohn.kramer819100% (42)

- Daughters of Nri by Reni K AmayoDocument272 pagesDaughters of Nri by Reni K Amayomutiu oluwatosinNo ratings yet

- John Brown Q&aDocument2 pagesJohn Brown Q&aSteve MenezesNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Jazz by Toni MorrisonDocument4 pagesThesis Statement For Jazz by Toni Morrisonbsdy1xsd100% (2)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (83)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentFrom EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- The Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (215)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklFrom EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsFrom EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- The Magical Approach: Seth Speaks About the Art of Creative LivingFrom EverandThe Magical Approach: Seth Speaks About the Art of Creative LivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindFrom EverandThere Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (71)

- The Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaFrom EverandThe Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaNo ratings yet

- Knocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldFrom EverandKnocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (64)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessFrom EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (60)

- Summary: The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living By Ryan Holiday: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living By Ryan Holiday: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNo ratings yet

- How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionFrom EverandHow to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (194)

- Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentFrom EverandWhy Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (753)