Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adhd and Lifestyle Habit in Chidren and Adolescent

Adhd and Lifestyle Habit in Chidren and Adolescent

Uploaded by

ariestianiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adhd and Lifestyle Habit in Chidren and Adolescent

Adhd and Lifestyle Habit in Chidren and Adolescent

Uploaded by

ariestianiCopyright:

Available Formats

Original

Juan Luis Párraga1

Beatriz Calleja Pérez2 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Sara López-Martín3

Jacobo Albert4

and lifestyle habits in children and

Daniel Martín Fernández-Mayoralas5

Ana Laura Fernández-Perrone5

adolescents

Ana Jiménez de Domingo5

Pilar Tirado6

Sonia López-Arribas7 1

Estudiante de Medicina. Universidad Europea de Madrid

Rebeca Suárez-Guinea8 2

Atención Primaria de Pediatría. Centro de Salud “Doctor Cirajas”. Madrid

Alberto Fernández-Jaén5,9

3

Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Centro Neuromottiva. Madrid

4

Facultad de Psicología. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

5

Servicio de Neurología Infantil. Hospital Universitario Quirónsalud. Madrid

6

Sección de Neurología Infantil. Hospital Universitario La Paz. Centro CADE Madrid

7

Servicio de Psiquiatría. Hospital “Gómez Ulla”. Madrid. Centro CADE. Madrid

8

Psiquiatría. Centro CADE. Madrid

9

Facultad de Medicina. Universidad Europea de Madrid

Introduction. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder Keywords: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Life Habits, Television, Videogames,

Study, Homework, Sleep

(ADHD) is one of the most prevalent disorders in the child

and adolescent population, with a known impact on learn-

ing, social relations and quality of life. However, the lifestyle Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64

habits of patients with this disorder have been poorly stud-

ied.

Material and methods. A total of 160 children and ad- Trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad y

olescents, aged between 6 and 16 years, participated in the hábitos de vida en niños y adolescentes

study. Half of them were treatment-naïve patients with a

clinical diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, Introducción. El trastorno por déficit de atención/hipe-

and without comorbidities. The remaining 80 participants ractividad (TDAH) es uno de los trastornos más prevalentes

were typically developing (TD) controls without known neu- en la población infanto-juvenil con un impacto ya conocido

rodevelopmental or psychiatric disorders. Parents of all par- sobre el aprendizaje, la relación social y la calidad de vida.

ticipants completed a questionnaire about their children´s Sin embargo, los hábitos de vida de los pacientes con este

lifestyle habits (e.g, daily hours of sleep, media use and trastorno han sido pobremente estudiados.

study).

Material y métodos. Un total de ciento sesenta niños

Results. The groups had a similar socioeconomic back- y adolescentes con edades comprendidas entre los 6 y los

ground and did not differ with respect to age and sex distri- 16 años (104 varones y 56 mujeres) participaron en este

bution. However, patients with ADHD spent more time than estudio. La mitad de ellos tenían un diagnóstico de TDAH

TD children studying, and less time watching TV, playing vid- de acuerdo a los criterios del DSM-IV-TR; eran pacientes sin

eo games, using computers and playing with other people. tratamiento y sin comorbilidades. El Group control estaba

They also slept fewer hours per night than children and ad- formado por 80 niños y adolescentes sin trastornos del neu-

olescents with TD. ADHD and TD groups spent similar time rodesarrollo o psiquiátricos conocidos. Las familias comple-

reading, listening to music and playing sports. taron un cuestionario sobre los hábitos de vida de sus hijos

Conclusions. The results of this study suggest that chil- e hijas (dedicación extraescolar -horas al día- a diferentes

dren and adolescents with ADHD have different lifestyle actividades durante la semana lectiva).

habits compared to age- and sex-matched controls. These Resultados. Los Groups tenían un nivel socioeconómico

findings are not explained by comorbid disorders or medica-

similar y no diferían en edad y sexo. Sin embargo, los pa-

tion/psychological treatment.

cientes con TDAH dedicaban más tiempo al estudio que los

Correspondence:

controles y menos a actividades como la TV, el ordenador,

Alberto Fernández-Jaén. los videojuegos y el juego con otras personas. Además, los

Hospital Universitario Quirónsalud. C/ Diego de Velázquez, 1, 28223 Pozuelo de Alarcón

(Madrid) pacientes con TDAH dormían menos horas diarias que los

Centro CADE. C/ Jimena Menéndez Pidal 8-A, 28023 Aravaca (Madrid, Spain)

Tel.: 914521900

controles. No se observaron diferencias entre los Groups en

E-mail: aferjaen@telefonica.net. el tiempo dedicado a la lectura, el deporte o la música.

158 Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64

Juan Luis Párraga, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and lifestyle habits in children and adolescents

Conclusiones. Los resultados del presente estudio su- METHODS

gieren que los niños y adolescentes con TDAH tienen hábitos

de vida diferentes a los niños y adolescentes con desarro-

llo típico. Estos hallazgos no se explican por la presencia de Participants

trastornos comórbidos o por el tratamiento farmacológico

o psicológico. A total of 160 children and adolescents, aged between

Palabras Clave: Trastorno de Déficit de Atención/Hiperactividad, Hábitos de Vida,

6 and 16 years, participated in the study. Half of them were

Televisión, Videojuegos, Estudio, Deberes, Sueño treatment-naïve patients with a clinical diagnosis of ADHD

according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, and without comorbidities.

The remaining 80 participants were TD controls without

known neurodevelopmental or psychiatric disorders. Clinical

diagnosis of ADHD was made according to DMS-IV-TR crite-

ria16 and international guidelines, as assessed by a multidis-

ciplinary team17-19. All patients were medication-naïve at the

time of the study and did not have any comorbid neurode-

INTRODUCTION

velopmental disorders, including intellectual disability, au-

tism spectrum disorder, learning, and language-related dis-

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one

orders. Further exclusion criteria included evidence of a

of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders1,2, af-

neurological disorder or a history of psychiatric disorders

fecting between 5-7% of children and adolescents. The car-

such as psychosis and bipolar disorder. TD controls were free

dinal symptoms of ADHD (inattention, hyperactivity, and

from neurodevelopmental, psychiatric or neurological disor-

impulsivity) have to be clearly present for at least 6 months ders, as assessed by the same procedure used in ADHD pa-

in two or more settings to an extent that is inappropriate for tients. All participants were Caucasian and lived in the Co-

person´s age/general cognitive level. Moreover, they should munidad de Madrid. All of them belonged to high

have a significant impact on social and/or school function- socio-economic status according to Graffar´s scale20.

ing3. Notably, ADHD symptoms and neuropsychological cor-

relates affect the quality of life of patients and their fami- Parents of all participants completed a questionnaire

lies4. Indeed, it has been shown that the severity of the about their children´s lifestyle habits (e.g, daily hours of

symptomatology and comorbidity are directly related to the sleep, media use or study). A full version of this question-

patients’ quality of life5. naire has been previously used in other studies21. Parents

were asked to complete the questionnaire indicating the

All neurodevelopmental disorders have a significant im- time spent by their children in several out-of-school activi-

pact on patients’ lifestyle habits whether due to the symp- ties during the five-day school week. The following variables

tomatology per se or the functional impairment they cause4. were measured: age, sex and amount of time (average num-

However, the lifestyle habits of children and adolescents ber of hours per day) that their children spend studying (in-

with neurodevelopmental disorders (including those diag- cluding, school homework assignments), watching TV, play-

nosed with ADHD) have been scarcely investigated6-8.. More- ing video games, listening to music, reading books (not

over, previous studies on this issue have generally focused related to school assignments), playing sports, playing with

on specific lifestyle habits (e.g., food, sleep or media use)9-14. friends or with family members, and sleeping. Informed con-

Surprisingly, although ADHD is characterized by impair- sent was obtained from all participants’ parents, with the

child giving assent.

ments in school and/or social functioning, study and leisure

time habits have been scarcely examined in these children

and adolescents with this disorder15. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The present study investigated the lifestyle habits of

Before statistical analysis, individual variables were as-

children and adolescents with ADHD in comparison to typi- sessed for outliers. They were defined as more than three

cally developing (TD) controls. We focused on the amount of interquartile ranges below the first quartile, or more than

time that children and adolescents with ADHD spend study- three interquartile ranges above the third quartile. Outliers

ing and doing homework assignments during the school were then replaced with the value 2 standard deviations

week. Additionally, we examined the amount of time they from the mean of each group and each dependent vari-

spend doing leisure-time activities, such as watching TV, able22. Twenty-six outliers were found and replaced (1.6%).

playing video games, listening to music or reading books. We Assumptions of normality were checked for each group

hypothesized that, relative to TD controls, patients with separately using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov procedure. As

ADHD would show different lifestyle habits. expected, the normality assumption was rejected in all de-

Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64 159

Juan Luis Párraga, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and lifestyle habits in children and adolescents

pendent variables (all ps<0.001). Thus, non-parametric controls, ADHD children spent more time on screen-related

tests were employed (Mann-Whitney statistic) to investi- activities (TV, video games, etc.) and less time on reading

gate possible differences between ADHD and TD controls in during the school week (differences were not found on

lifestyle habits (i,e., the average number of hours per day weekends or holidays). By contrast, differences between

dedicated to each activity during the school week). The groups were not found regarding the number of hours of

false discovery rate (FDR) procedure was applied to control studying and sleeping. However, although the study showed

for multiple comparisons (n=9). Effect sizes were estimated that lifetime habits could be influenced by comorbidity (pri-

using r (r=Z/√N; (23)), which is similar to Cohen´s d for marily, anxiety and mood disorders), it did not examine if

non-parametric tests. Analyses were performed using SPSS such comorbid disorders had a significant impact on the

20 (SPPS Inc, Chicago, USA). lifestyle habits of ADHD patients. Moreover, this study did

not control for other comorbid disorders (e.g, dyslexia) that

might have influenced habits concerning reading, studying

RESULTS and playing. Similarly, Tong and colleagues25 reported that

children with ADHD spent more time on screen-related ac-

The mean ages and sex distribution of groups can be tivities without affecting other habits such as physical activ-

found in Table 1. Groups did not differ in mean age (Z=- ity25. However, they did not control for comorbid disorders

0.83, p=0.41) or the proportion of participants for each age or medication use.

year (from 6 to 16 years in one-year intervals: χ2=2.42,

p=0.99). Groups neither differed significantly concerning Interestingly, lifestyle habits of 25 Spanish adolescents

sex (χ2=0.99, p=0.32). with ADHD compared to 184 Spanish adolescents without

the disorder were examined15. Results from this study sug-

As detailed in Table 2 and Figures 1 and 2, differences gested that patients with ADHD spent more time than con-

between groups were found in six of the lifestyle habits as- trols playing video games and watching TV (not only on

sessed. Specifically, children and adolescents with ADHD school days, unlike that in Holton’s study), but spent less

spent more time than TD controls studying. By contrast, TD time with family and friends15. In adults, Weissenberger and

controls spend more time watching television, using a com- colleagues6 reported that individuals showing ADHD symp-

puter and playing video games than those with ADHD. Thus, toms spend less time watching TV but more time carrying

the time dedicated to playing in the TD group was greater out physical activities than those with fewer ADHD symp-

than in the ADHD group. Finally, we also observed that chil- toms. Although these studies provide evidence that ADHD

dren and adolescents with ADHD slept fewer hours per night affects lifestyle habits, their results could be heavily influ-

than TD controls (see Table 2 and Figure 2). enced by comorbid disorders. Moreover, given the lack of

control for multiple comparisons, some of the significant

results might be due to chance (false positives).

DISCUSSION

The relation between cardinal ADHD symptoms and

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that time spend on screen-related activities has been examined

examined lifestyle habits in medication-naïve children and by several groups. However, studies have yielded discrepant

adolescents with ADHD without any comorbid disorders. As results. A number of investigations have shown a significant

mentioned above, there are only a few studies on lifestyle relationship between ADHD symptoms and time spend

habits of ADHD patients6-8, and most of them did not control watching TV and playing videogames26-28. However, results

for multiple testing 25. from these previous studies do not clarify whether neuro-

psychological deficits underlying ADHD (e.g., motivation

Holton and colleagues7 examined the lifestyle habits of and/or sustained attention problems) lead to spend more

184 children with ADHD. They found that, compared to TD time watching TV and playing video games or, by contrast,

whether the use of TV and video games contribute to cogni-

tive deficits and symptoms characteristic of ADHD29,30. Nev-

ertheless, other studies have found improvements in cogni-

Table 1 Demographic variables tive functions after watching TV and/or playing

videogames27,31,32. Contrarily, other studies have failed to

TDAH Control find a significant association between ADHD and me-

dia-use34,35. Although our study was not designed to analyze

Sex (m/f)* 55/25 49/31 the relationship between screen time and ADHD, our results

Age 10.1 ±2.39 9.78 ±2.38 do not support this hypothesis. Our patients with ADHD

spent less time on video games and TV than the children in

*m: male; f: female

the control group, although they were naïve patients with-

160 Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64

Juan Luis Párraga, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and lifestyle habits in children and adolescents

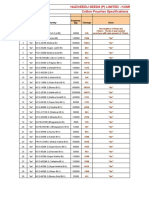

Table 2 Descriptive statistics and results of non-parametric tests used to examine between-group differences

on the amount of time (average hours per day) spend in each activity

ADHD Skewness Kurtosis TD controls Skewness Kurtosis U Mann p q** r***

(mean±SD) (mean±SD) Whitney

(Z)

No. of hours studying* 1.94±1.08 1.4 4.9 1.49±0.85 0.4 -0.7 -2.69 0.007 0.03 0.21

No. of hours watching TV* 0.89±0.63 0.4 -0.3 1.23±0.92 1.4 3.2 -2.32 0.021 0.04 0.18

No. of hours using computer* 0.28±0.5 2 3.8 0.41±0.53 1.4 1.3 -2.22 0.027 0.04 0.17

No. of hours playing video game* 0.21±0.4 1.8 2.2 0.52±0.72 1.7 2.5 -3.07 0.002 0.02 0.24

No. of hours listening to music* 0.27±0.42 1.7 2.6 0.38±0.48 1.1 0.4 -1.66 0.097 0.1

No. of hours reading* 0.44±0.42 1.6 3.7 0.4±0.38 1.1 2.4 -0.5 0.617 0.08

Physical activity* 0.7±0.61 0.7 1.3 0.81±0.61 0.4 -0.3 -1.05 0.294 0.29

No. of hours playing with others* 0.72±0.75 1.1 0.9 1.01±0.89 1.4 3.8 -2.25 0.024 0.04 0.18

No. of hours sleeping* 9.02±1.17 0.03 -0.2 9.41±0.98 -0.8 0.5 -2.62 0.009 0.03 0.21

*Hours per day devoted to each activity during the school week; ** P adjusted for multiple comparisons using the FDR procedure24;*** Effect size

calculated as r=Z/√N, where Z is the absolute value of the statistic and N is the total number of participants23

NO. OF HOURS PLAYING VIDEO GAME

2,5 2,5

NO. OF HOURS WATCHING TV

2,5

NO. OF HOURS STUDYING

2,0 2,0 2,0

1,5 1,5 1,5

1,0 1,0 1,0

0,5 0,5 0,5

0 0 0

TDAH Control TDAH Control TDAH Control

Group Group Group

2,5 2,5

NO. OF HOURS USING COMPUTER

NO. OF HOURS PLAYING WITH

2,0 2,0

1,5 1,5

OTHERS

1,0 1,0

0,5 0,5

0 0

TDAH Control TDAH Control

Group Group

Figure 1 Lifestyle habits showing significant differences between ADHD and TD groups (error bars represent ±1

standard error of the mean). The average number of hours per day dedicated to each activity during the

school week was assessed (0, minimum, and, 10 hours, maximum)

Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64 161

Juan Luis Párraga, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and lifestyle habits in children and adolescents

10 problems may be temporary or permanent, they may con-

tribute to ADHD symptomology, and, in some cases, they

may worsen with psychostimulants pharmacological treat-

ments48-50. Present results suggest that certain sleep-related

difficulties (fewer hours of sleep per night on average) may

NO. OF HOURS SLEEPING

8 be even present in medication-naïve children and adoles-

cents with the disorder.

Little research has been done to examine the time ded-

icated by patients with ADHD to studying and doing home-

6 work outside of class. Of note, the time dedicated to these

two activities seems to be related to academic perfor-

mance51-54. This association has also been observed amongst

ADHD patients55, with effect sizes from medium to large54.

Although children and adolescents with ADHD typically

4 have poor academic performance and problems related to

TDAH Control the failure of completing homework assignments, a few

Group studies have investigated how many hours per day ADHD

patients spend studying and doing homework assign-

ments56,57. This lack of information about the time dedicated

Figure 2 Differences between ADHD and TD by individuals with ADHD to studying outside of class is sur-

groups on the average number of sleep prising because a negative impact on school functioning is a

hours per night during school days diagnostic criterion of ADHD3. The clinical diagnosis and its

(error bars represent ±1 standard error treatment should probably be reviewed in those patients

of the mean) who, although they meet the diagnostic criteria for ADHD,

do not dedicate time to studying and doing homework as-

signments outside of class. An alternative or additional dis-

order could be present in such cases.

out comorbid disorders; the presence of mood disorders,

Holton and colleagues7 found that the percentage of

anxiety disorders or behavioral problems seem to be signifi-

individuals who spend more than two hours to homework

cantly related to increased exposure or dedication to me-

assignments was slightly higher in the ADHD group com-

dia-use36-39.Previous studies have also shown that children

pared to the TD group, though these results were not statis-

and adolescents with ADHD spend less time interacting with

tically significant. In the current study, medication-naïve

peers and family members15. Whether due to the patients’

and non-comorbid patients with ADHD had to dedicate 30%

socio-cognitive difficulties, their symptoms or the social im-

more time than TD controls to studying. It is therefore likely

pact of the disorder, individuals with ADHD often encounter

that the quality of life of ADHD patients was affected4,5. No-

problems in social interactions with peers and adults (teach-

tably, it should be noted that current findings do not sup-

ers and parents)40-42. Some authors have used these argu-

port the notion that children and adolescents with ADHD

ments, as well as the presence of comorbid developmental

dedicate less time to studying than individuals without the

coordination disorder, to explain why patients with the dis-

disorder.

order devote less time to sports and physical activities43-45.

This relation could be influenced by the presence of a coach Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. The

supervising the activity43. ADHD group devoted slightly less generalization of the current results to the overall popula-

time than the control group to playing sports, although this tion of patients with ADHD would be limited because “pure”

trend is not significant. The absence of comorbidity in our cases of ADHD (without comorbidity) are the exception

sample of patients with ADHD and the fact that, in most rather than the rule. Further research on the influence of

cases, they participated in organized and supervised sport- most common comorbidities on the lifestyle habits of pa-

ing activities could have influenced present results. tients with ADHD is therefore needed. Furthermore, future

research should examine the effect that psychopharmaco-

Although we did not find significant differences be-

logical and non-psychopharmacological interventions could

tween ADHD and control groups in the amount of time have on lifestyle habits. It would be also interesting to ex-

spent reading or listening to music, we observed that pa- amine how spending more time studying and less time play-

tients slept less than controls. Sleep-related problems (pri- ing can affect the quality of life of children and adolescents

marily those related to sleep onset difficulties) have been with ADHD. Finally, the current study did not examine the

broadly discussed in the literature11,46,47. These sleep-related

162 Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64

Juan Luis Párraga, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and lifestyle habits in children and adolescents

living conditions and lifestyle habits of the families, or how hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J Can Acad

patients’ habits might be influenced by their parents’ life- Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(2):92-102.

10. Betancourt-Fursow de Jimenez YM, Jimenez-Leon JC, Jimenez-

style.

Betancourt CS. Trastorno por deficit de atencion ehiperactividad

y trastornos del sueno. Rev Neurol. 2006;42(Suppl 2):S37-51.

Regardless of these limitations, this study suggests that

11. Chamorro M, Lara JP, Insa I, Espadas M, Alda-Diez JA. Evaluacion

lifestyle habits of children and adolescents with ADHD are y tratamiento de los problemas de sueno en ninos diagnosticados

associated to or mediated by the disorder itself and that de trastorno por deficit de atencion/hiperactividad: actualizacion

these habits are different from those observed in TD children de la evidencia. Rev Neurol. 2017;64(9):413-21.

and adolescents. Because patients with ADHD were medica- 12. Lingineni RK, Biswas S, Ahmad N, Jackson BE, Bae S, Singh KP.

tion-naïve and did not have comorbid disorders, current re- Factors associated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

among US children: results from a national survey. BMC Pediatr.

sults seem to be related to the disorder itself. Results ob- 2012;12:50.

tained in the control group are comparable to those obtained 13. Bertholf RL, Goodison S. Television viewing and attention

in previous studies using similar procedures21, thus support- deficits in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):511-2; author reply

ing the current findings. Future studies examining the life- 511-2.

style habits of patients with the disorder in different coun- 14. Ray M, Jat KR. Effect of electronic media on children. Indian

Pediatr. 2010;47(7):561-8.

tries and/or regions are needed to gain greater insight into

15. Aierbe A, Medrano C. Consumo mediático y actividades

the impact of ADHD on different aspects of patients’ lives. alternativas: un estudio comparativo entre adolescentes con

Moreover, such studies would facilitate a more in-depth TDAH y estándar. Infad Rev Psicol. 2011;2:117-26.

analysis of the alternative diagnostic hypotheses mentioned 16. American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV.

above. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-

TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association;

2000. p. 943.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 17. Alda JÁ, Fernández Anguiano M, Grupo de Trabajo de la Guía

de Práctica Clínica sobre el Trastorno por Déficit de Atención

con Hiperactividad (TDAH) en Niños y Adolescentes, Fundación

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y San Juan de Dios, España. Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación,

Competitividad (MINECO) of Spain (PSI2017-84922-R). España. Ministerio de Sanidad Política Social e Igualdad. Guía

de práctica clínica sobre el trastorno por déficit de atención

con hiperactividad (TDAH) en niños y adolescentes. Madrid:

REFERENCES Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación; 2010.

18. Kendall T, Taylor E, Perez A, Taylor C, Guideline Development G.

1. Willcutt EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/ Diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity

hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics. disorder in children, young people, and adults: summary of NICE

2012;9(3):490-9. guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1239.

2. Fernandez-Jaen A, Lopez-Martin S, Albert J, Martin Fernandez- 19. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,

Mayoralas D, Fernandez-Perrone AL, Calleja-Perez B, et al. Steering Committee on Quality Improvement Management,

Trastorno por deficit de atencion/hiperactividad: perspectiva Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M,

desde el neurodesarrollo. Rev Neurol. 2017;64(s01):S101-S4. Feldman HM, et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/

manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics.

Londres: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. XLIV, 947 p. p. 2011;128(5):1007-22.

4. Fernandez-Jaen A, Martin Fernandez-Mayoralas D, Fernandez- 20. Graffar M. Une methode de classifcation sociales d´echantillons

Perrone AL, Calleja-Perez B, Albert J, Lopez-Martin S, et al. de population. Courrier. 1956;6:445-59.

Disfuncion en el trastorno por deficit de atencion/hiperactividad: 21. Román B, Serra L, Ribas L, Pérez C, Aranceta J. Crecimiento y

evaluacion y respuesta al tratamiento. Rev Neurol. 2016;62 desarrollo: actividad física. Estimación del nivel de actividad

(Suppl 1):S79-84. física mediante el Test Corto Krece Plus. Resultados en la

5. Danckaerts M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, población española. In: Serra L, Aranceta J, Rodríguez-Santos

Dopfner M, Hollis C, et al. The quality of life of children with F, editors. Crecimiento y desarrollo Estudio enKid Krece Plus

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Eur Barcelona: Masson, S.A.; 2003. p. 57-98.

Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):83-105. 22. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6th ed.

6. Weissenberger S, Ptacek R, Vnukova M, Raboch J, Klicperova- Harlow: Pearson; 2014. ii, p. 1056.

Baker M, Domkarova L, et al. ADHD and lifestyle habits in Czech 23. Field AP. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 2nd ed. London:

adults, a national sample. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018; SAGE Publications; 2005. xxxiv, p. 779.

14:293-9. 24. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a

7. Holton KF, Nigg JT. The Association of Lifestyle Factors and practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc

ADHD in Children. J Atten Disord. 2016. Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57(289-300).

8. Bijlenga D, van der Heijden KB, Breuk M, van Someren EJ, Lie ME, 25. Tong L, Xiong X, Tan H. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Boonstra AM, et al. Associations between sleep characteristics, Disorder and Lifestyle-Related Behaviors in Children. PLoS One.

seasonal depressive symptoms, lifestyle, and ADHD symptoms in 2016;11(9):e0163434.

adults. J Atten Disord. 2013;17(3):261-75. 26. Nikkelen S. The role of media enterainment in children´s

9. Owens JA. A clinical overview of sleep and attention-deficit/ and adolescent´s ADHD-related behaviors. Amsterdam: CPI

Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64 163

Juan Luis Párraga, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and lifestyle habits in children and adolescents

Koninklijke Wöhrmann; 2015. 2011;39(6):339-48.

27. Acevedo-Polakovich ID, Lorch EP, Milich R, Ashby RD. 42. Fernandez-Jaen A, Martin Fernandez-Mayoralas D, Lopez-

Disentangling the relation between television viewing Arribas S, Pardos-Veglia A, Muniz-Borrega B, Garcia-Savate

and cognitive processes in children with attention-deficit/ C, et al. Social and leadership abilities in attention defi cit/

hyperactivity disorder and comparison children. Arch Pediatr hyperactivity disorder: relation with cognitive-attentional

Adolesc Med. 2006;160(4):354-60. capacities. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2012;40(3):136-46.

28. Swing EL, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Walsh DA. Television 43. Wu X, Ohinmaa A, Veugelers PJ. The Influence of Health

and video game exposure and the development of attention Behaviours in Childhood on Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity

problems. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):214-21. Disorder in Adolescence. Nutrients. 2016;8(12).

29. Mistry KB, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM, Borzekowski DL. 44. Harvey WJ, Reid G, Bloom GA, Staples K, Grizenko N, Mbekou

Children’s television exposure and behavioral and social V, et al. Physical activity experiences of boys with and without

outcomes at 5.5 years: does timing of exposure matter? ADHD. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2009;26(2):131-50.

Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):762-9. 45. Gapin JI, Labban JD, Etnier JL. The effects of physical activity on

30. Stevens T, Mulsow M. There is no meaningful relationship attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: the evidence.

between television exposure and symptoms of attention-deficit/ Prev Med. 2011;52 Suppl 1:S70-4.

hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):665-72. 46. Owens JA, Maxim R, Nobile C, McGuinn M, Msall M. Parental

31. Rosenqvist J, Lahti-Nuuttila P, Holdnack J, Kemp S, Laasonen and self-report of sleep in children with attention-deficit/

M. Relationship of TV watching, computer use, and reading to hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;

children’s neurocognitive functions. J Applied Develop Psychol. 154(6):549-55.

2016;46:11-21. 47. Betancourt-Fursow de Jimenez YM, Jimenez-Leon JC,

32. Hubert-Wallander B, Green CS, Sugarman M, Bavelier D. Changes Jimenez-Betancourt CS. Trastorno por deficit de atención de

in search rate but not in the dynamics of exogenous attention hiperactividad y trastornos del sueño. Rev Neurol. 2006;42

in action videogame players. Atten Percept Psychophys. (Suppl 2):S37-51.

2011;73(8):2399-412. 48. Lycett K, Mensah FK, Hiscock H, Sciberras E. A prospective

33. Cao F, Su L, Liu T, Gao X. The relationship between impulsivity study of sleep problems in children with ADHD. Sleep Med.

and Internet addiction in a sample of Chinese adolescents. Eur 2014;15(11):1354-61.

Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):466-71. 49. Idiazabal-Aletxa MA, Aliagas-Martinez S. Sueño en los trastornos

34. Bioulac S, Arfi L, Bouvard MP. Attention deficit/hyperactivity del neurodesarrollo. Rev Neurol. 2009;48(Suppl 2):S13-6.

disorder and video games: a comparative study of hyperactive 50. Fernández-Jaén A, Martín D, Fernández-Perrone A, Calleja-

and control children. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):134-41. Pérez B. Psicofarmacología del TDAH: estimulantes. In: Soutullo

35. Ferguson CJ. The influence of television and video game use C, editor. Guía esencial de psicofarmacología del niño y del

on attention and school problems: a multivariate analysis with adolescente. Madrid: Panamericana; 2017. p. 79-92.

other risk factors controlled. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(6):808-13. 51. Mau W, Lynn R. Gender differences in homework and test scores

36. Mundy LK, Canterford L, Olds T, Allen NB, Patton GC. The in Mathematics, Reading and Science at tenth and twelfth

Association Between Electronic Media and Emotional and grade. Psychol Evol Gender. 2010;2(2):119-25.

Behavioral Problems in Late Childhood. Acad Pediatr. 2017; 52. Valle A, Regueiro B, Nunez JC, Rodriguez S, Pineiro I, Rosario P.

17(6):620-4. Academic Goals, Student Homework Engagement, and Academic

37. de Wit L, van Straten A, Lamers F, Cuijpers P, Penninx B. Are Achievement in Elementary School. Front Psychol. 2016;7:463.

sedentary television watching and computer use behaviors 53. Suarez N, Regueiro B, Epstein JL, Pineiro I, Diaz SM, Valle A.

associated with anxiety and depressive disorders? Psychiatry Homework Involvement and Academic Achievement of Native

Res. 2011;186(2-3):239-43. and Immigrant Students. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1517.

38. Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, Allender S. The associations between 54. Cooper H, Robinson JC, Patall EA. Does homework improve

sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: a academic achievement? A synthesis of research. Rev Educat

systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):108. Research. 2006;76:1-62.

39. Rikkers W, Lawrence D, Hafekost J, Zubrick SR. Internet use and 55. Langberg JM, Dvorsky MR, Molitor SJ, Bourchtein E, Eddy

electronic gaming by children and adolescents with emotional LD, Smith Z, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of the importance

and behavioural problems in Australia - results from the second of homework assignment completion for the academic

Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. performance of middle school students with ADHD. J Sch

BMC Public Health. 2016;16:399. Psychol. 2016;55:27-38.

40. Pardos A, Fernandez-Jaen A, Fernandez-Mayoralas DM. 56. Merrill BM, Morrow AS, Altszuler AR, Macphee FL, Gnagy EM,

Habilidades sociales en el trastorno por deficit de atencion/ Greiner AR, et al. Improving homework performance among

hiperactividad. Rev Neurol. 2009;48(Suppl 2):S107-11. children with ADHD: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin

41. Fernandez-Jaen A, Fernandez-Mayoralas DM, Lopez-Arribas Psychol. 2017;85(2):111-22.

S, Garcia-Savate C, Muniz-Borrega B, Pardos-Veglia A, et al. 57. Mautone JA, Marshall SA, Costigan TE, Clarke AT, Power TJ.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and its relation to social Multidimensional assessment of homework: an analysis of

skills and leadership evaluated with an evaluation system of the students with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(7):600-9.

behavior of children and adolescents (BASC). Actas Esp Psiquiatr.

164 Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47(4):158-64

You might also like

- S4965V2166 FS Preliminary PDFDocument20 pagesS4965V2166 FS Preliminary PDFmartinuruguayNo ratings yet

- Trastorno de Espectro Autista: Una guía con 10 puntos clave para diseñar la estrategia más adecuada para tu hijoFrom EverandTrastorno de Espectro Autista: Una guía con 10 puntos clave para diseñar la estrategia más adecuada para tu hijoNo ratings yet

- UtahDocument7 pagesUtahFNo ratings yet

- Trastorno Por Déficit de Atención Con Hiperactividad: de La Teoría A La PrácticaDocument11 pagesTrastorno Por Déficit de Atención Con Hiperactividad: de La Teoría A La Prácticajose manuelNo ratings yet

- SNAPIV Vs Impresion ClínicaDocument8 pagesSNAPIV Vs Impresion ClínicaLittle HiuxNo ratings yet

- Función y Utilidad de Los Cuestionarios en El Diagnóstico de TDAHDocument22 pagesFunción y Utilidad de Los Cuestionarios en El Diagnóstico de TDAHVioleta SotoNo ratings yet

- TDAHDocument24 pagesTDAHchristiandNo ratings yet

- Prevalencia de Trastornos Del Neurodesarrollo, Comportamiento y Aprendizaje en Atención PrimariaDocument9 pagesPrevalencia de Trastornos Del Neurodesarrollo, Comportamiento y Aprendizaje en Atención PrimariaGiiszs AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Guiatdahreinasofia 120110055412 Phpapp02Document36 pagesGuiatdahreinasofia 120110055412 Phpapp02lul 49No ratings yet

- TDAHDocument10 pagesTDAHCarlos Padilla SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Actividad 5 Ensayo Tdah Irais Esmeralda Penilla RoblesDocument12 pagesActividad 5 Ensayo Tdah Irais Esmeralda Penilla RoblesIrais Penilla RoblesNo ratings yet

- Tdah 2Document11 pagesTdah 2guadalupe mendezNo ratings yet

- Guia para Padres y Educadores TDAHDocument36 pagesGuia para Padres y Educadores TDAHjmaa2100% (1)

- Tdahconsensomultidisciplinar 2009Document25 pagesTdahconsensomultidisciplinar 2009brendavanessameraaNo ratings yet

- Guía TDAH. EspañolDocument2 pagesGuía TDAH. EspañolJuan Carlos Muñoz SalmerónNo ratings yet

- Trastorno Fonologico y Conciencia Fonologica en TelDocument76 pagesTrastorno Fonologico y Conciencia Fonologica en Telgrace prambsNo ratings yet

- TDAHDocument23 pagesTDAHJesus LopeezNo ratings yet

- TCC en TdahDocument67 pagesTCC en Tdahalexis_castillejo_1No ratings yet

- Efectos de Los Psicoestimulantes en El Desempeño Cognitivo y Conductual de Los Niños Con Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad Subtipo CombinadoDocument8 pagesEfectos de Los Psicoestimulantes en El Desempeño Cognitivo y Conductual de Los Niños Con Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad Subtipo CombinadoJahir GomezNo ratings yet

- 50 Preguntas y Respuestas Sobre ThdaDocument29 pages50 Preguntas y Respuestas Sobre ThdaEduardo Lopez JimenezNo ratings yet

- Baremación Edah AdolescentesDocument10 pagesBaremación Edah AdolescentesIrune Zarraga100% (1)

- TdahDocument86 pagesTdahMartina NavarreteNo ratings yet

- Trabajo de Investigación TDAHDocument6 pagesTrabajo de Investigación TDAHGrisel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Rev Sopnia 2016-1Document80 pagesRev Sopnia 2016-1Jose Luis Gonzalez CelisNo ratings yet

- Trabajo TDAHDocument41 pagesTrabajo TDAHyanna violetaNo ratings yet

- ENSAYO ACADÉMICO. PROGRAMA DE INTERVENCION TDAH. Dra Iraima V - Martínez. MDocument12 pagesENSAYO ACADÉMICO. PROGRAMA DE INTERVENCION TDAH. Dra Iraima V - Martínez. MIraima 12No ratings yet

- Manual de Diagnc3b3stico y Manejo Del Tdah Enfoque MultidisciplinarioDocument159 pagesManual de Diagnc3b3stico y Manejo Del Tdah Enfoque MultidisciplinarioErick Escalante100% (2)

- 45-Texto Del Artículo-68-1-10-20181022Document14 pages45-Texto Del Artículo-68-1-10-20181022Isabel EccoñaNo ratings yet

- Intervencion en Niños 2Document34 pagesIntervencion en Niños 2Luis Alfredo Ramírez SernaqueNo ratings yet

- Intervencion en Niños 2Document37 pagesIntervencion en Niños 2Luis Ramirez SernaqueNo ratings yet

- Consenso Multidisciplinar en TDAH Infancia y Adolescencia - Gob - AragonDocument44 pagesConsenso Multidisciplinar en TDAH Infancia y Adolescencia - Gob - AragonElena RosasNo ratings yet

- Tdha Test de TdhaDocument21 pagesTdha Test de Tdharonysmar rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Gui - A TDAH IMPRESA PDFDocument24 pagesGui - A TDAH IMPRESA PDFmartin salgueiroNo ratings yet

- Revista SOPNIA Marzo 2013Document173 pagesRevista SOPNIA Marzo 2013Clarita MoralesNo ratings yet

- Utilización de Técnicas Complementarias en Niños Con Trastornos Del Espectro Autista: Una Revisión SistemáticaDocument33 pagesUtilización de Técnicas Complementarias en Niños Con Trastornos Del Espectro Autista: Una Revisión SistemáticaOscar David CedenoNo ratings yet

- Transtorno de Deficit de Atenciòn e Hiperactividad ImprimirDocument5 pagesTranstorno de Deficit de Atenciòn e Hiperactividad ImprimirMichaelRodríguez100% (1)

- Escala WFIRS DescripcionDocument15 pagesEscala WFIRS DescripcionDamian AgatsumaNo ratings yet

- (Evolutionary Issues in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) From Risk Factors To Comorbidity and Social and Academic Impact)Document9 pages(Evolutionary Issues in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) From Risk Factors To Comorbidity and Social and Academic Impact)MARIA HEREDERO HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Tdah TeptDocument11 pagesTdah TeptNiebla JohansonNo ratings yet

- Articulo Sobre Salud Mental y EmocionalDocument169 pagesArticulo Sobre Salud Mental y EmocionalSayuri MuñozNo ratings yet

- Updates in Pharmacologic Strategies in Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder - En.esDocument16 pagesUpdates in Pharmacologic Strategies in Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder - En.esIVAN ALVAREZNo ratings yet

- Trastornos Por Deficit de AtencionDocument8 pagesTrastornos Por Deficit de AtencionYo Promuevo A San IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Articulos TDAHDocument10 pagesArticulos TDAHRenato AymeNo ratings yet

- Matriz Art TDAHDocument20 pagesMatriz Art TDAHKelly Johanna Martinez BermudezNo ratings yet

- Utilidad de La Escala Wender-Utah y de Las Escalas de Síntomas para El TDAH en Adultos PDFDocument10 pagesUtilidad de La Escala Wender-Utah y de Las Escalas de Síntomas para El TDAH en Adultos PDFPacoNo ratings yet

- Utilidad de La Escala Wender-Utah y de Las Escalas de Síntomas para El TDAH en Adultos PDFDocument10 pagesUtilidad de La Escala Wender-Utah y de Las Escalas de Síntomas para El TDAH en Adultos PDFPacoNo ratings yet

- 50 Preguntas y Respuestas Sobre ThdaDocument29 pages50 Preguntas y Respuestas Sobre ThdaDaniela Díaz SantibáñezNo ratings yet

- TdahDocument19 pagesTdahElba GalanNo ratings yet

- 50 Preguntas y Respuestas Sobre Tdah - Nestor SzermanDocument29 pages50 Preguntas y Respuestas Sobre Tdah - Nestor SzermanAlejandro Díaz RivasNo ratings yet

- Revista-SOPNIA 201908Document118 pagesRevista-SOPNIA 201908Dana BelenNo ratings yet

- TDAH Posibles SolucionesDocument9 pagesTDAH Posibles SolucionesAlejandraNo ratings yet

- Consenso Multidisciplinar en TdahDocument44 pagesConsenso Multidisciplinar en TdahThuaretNo ratings yet

- Maria Luisa Jimenez Izquierdo01Document8 pagesMaria Luisa Jimenez Izquierdo01Rute Road TripNo ratings yet

- Articulo EbscoDocument7 pagesArticulo EbscoDiana CamachoNo ratings yet

- TDAH: Trastorno por Déficit de Atención e HiperactividadFrom EverandTDAH: Trastorno por Déficit de Atención e HiperactividadRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- TDAH y Focalización: Técnicas para hombres y mujeres adultos con TDAH para potenciar la autodisciplina, la productividad, la gestión del tiempo y el control emocional, superando la procrastinación, las distracciones y el agotamiento.From EverandTDAH y Focalización: Técnicas para hombres y mujeres adultos con TDAH para potenciar la autodisciplina, la productividad, la gestión del tiempo y el control emocional, superando la procrastinación, las distracciones y el agotamiento.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (29)

- Vivir con TDAH: Una guía completa para hombres y mujeres adultos con TDAH para lograr el control emocional, aumentar la productividad, mejorar las relaciones y lograr el éxito en la vida.From EverandVivir con TDAH: Una guía completa para hombres y mujeres adultos con TDAH para lograr el control emocional, aumentar la productividad, mejorar las relaciones y lograr el éxito en la vida.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (33)

- FXSQ - PAVE FCU-Daikin-VRV-CutsheetDocument1 pageFXSQ - PAVE FCU-Daikin-VRV-Cutsheetsergio.anacletoNo ratings yet

- General Biology 1 Final Exam 2nd QuarterDocument9 pagesGeneral Biology 1 Final Exam 2nd Quarterjoei Arquero100% (1)

- 2 Nutrient Management For Hydroponics COOKDocument33 pages2 Nutrient Management For Hydroponics COOKhyperviperNo ratings yet

- PCW Applicant's Information SheetDocument1 pagePCW Applicant's Information SheetGrateful FeatureNo ratings yet

- Samuel, Bucher & Suzuki - CAP 5, The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical PsychologyDocument9 pagesSamuel, Bucher & Suzuki - CAP 5, The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical PsychologyCarla AbarcaNo ratings yet

- Fruits 75 (6), 281-287 Effect of Fertilizer Treatments On Fruit Nutritional Quality of Plantain Cultivars and Derived HybridsDocument7 pagesFruits 75 (6), 281-287 Effect of Fertilizer Treatments On Fruit Nutritional Quality of Plantain Cultivars and Derived HybridsSol InvictusNo ratings yet

- 2012 FDA Warning Letter To AlereDocument8 pages2012 FDA Warning Letter To AlereWhatYou HaventSeenNo ratings yet

- Understanding DUI Laws in CaliforniaDocument6 pagesUnderstanding DUI Laws in CaliforniaSan Fernando Valley Bar AssociationNo ratings yet

- Cotton Pouches SpecificationsDocument2 pagesCotton Pouches SpecificationspunnareddytNo ratings yet

- Forest Fire Detection Using Image ProcessingDocument16 pagesForest Fire Detection Using Image ProcessingChilupuri Sreeya100% (1)

- ESP - MAK, Arthur Dun Ping Et Al. (2019)Document7 pagesESP - MAK, Arthur Dun Ping Et Al. (2019)Rafael ConcursoNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineers 05-2022Document180 pagesCivil Engineers 05-2022PRC Baguio60% (5)

- Data Bahan BakuDocument5 pagesData Bahan BakuTaofik NurdiansahNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Gas Turbine Operation MaintenanceDocument21 pagesFundamentals of Gas Turbine Operation MaintenanceAndrey Ekkert100% (2)

- 11) en Dzulkifli Mat Hashim - WHR2010 - Unraveling The Issue of Alcohol - FinalDocument66 pages11) en Dzulkifli Mat Hashim - WHR2010 - Unraveling The Issue of Alcohol - FinalAshyura25No ratings yet

- Case Study 1Document10 pagesCase Study 1api-242123281No ratings yet

- Commission Structure Agency Channel FCs Wef 04 Oct 2023Document47 pagesCommission Structure Agency Channel FCs Wef 04 Oct 2023Sanket D ZankarNo ratings yet

- Education Vs TrainingDocument3 pagesEducation Vs TrainingMark Lyndon M OrogoNo ratings yet

- Polymer StructureDocument2 pagesPolymer StructureElvince Tuazon BernardoNo ratings yet

- Urine Preservatives-Collection and Transportation For 24-Hour Urine SpecimensDocument5 pagesUrine Preservatives-Collection and Transportation For 24-Hour Urine SpecimensFaryalBalochNo ratings yet

- c11 - The Gallbladder and The Biliary System ExamDocument10 pagesc11 - The Gallbladder and The Biliary System ExamMarcus HenryNo ratings yet

- Fibrinolitiktrombolitik, Antikoagulan Dan AntiplateletDocument31 pagesFibrinolitiktrombolitik, Antikoagulan Dan AntiplateletAnggra OlgabellaNo ratings yet

- CE109 Infiltration Horton's Equation March 10,2023Document32 pagesCE109 Infiltration Horton's Equation March 10,2023angusdelosreyes23No ratings yet

- A American Sex SurveyDocument27 pagesA American Sex SurveyRamesh RajagopalanNo ratings yet

- What You Need To Know InfographicDocument1 pageWhat You Need To Know InfographicBitcoDavidNo ratings yet

- ConLaw II - Class NotesDocument20 pagesConLaw II - Class NotesAngelaNo ratings yet

- SUMMARYDocument16 pagesSUMMARYStanley OmezieNo ratings yet

- Notice: Committees Establishment, Renewal, Termination, Etc.: Designated Organ Procurement Service Area Hospital Waiver RequestDocument2 pagesNotice: Committees Establishment, Renewal, Termination, Etc.: Designated Organ Procurement Service Area Hospital Waiver RequestJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Karlissafirman Resume This OneDocument3 pagesKarlissafirman Resume This Oneapi-294290655No ratings yet