Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Long-Term E Ects of Discontinuation From Antipsychotic Maintenance Following First-Episode Schizophrenia and Related Disorders

Uploaded by

wen zhangOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Long-Term E Ects of Discontinuation From Antipsychotic Maintenance Following First-Episode Schizophrenia and Related Disorders

Uploaded by

wen zhangCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Long-term effects of discontinuation from antipsychotic

maintenance following first-episode schizophrenia and

related disorders: a 10 year follow-up of a randomised,

double-blind trial

Christy L M Hui, William G Honer, Edwin H M Lee, Wing Chung Chang, Sherry K W Chan, Emily S M Chen, Edwin P F Pang, Simon S Y Lui,

Dicky W S Chung, Wai Song Yeung, Roger M K Ng, William T L Lo, Peter B Jones, Pak Sham, Eric Y H Chen

Summary

Background The long-term consequences of discontinuing antipsychotic medication after successful treatment of Lancet Psychiatry 2018

first-episode psychosis are not well studied. We assess the relation between early maintenance therapy decisions Published Online

in first-episode psychosis and the subsequent clinical outcome at 10 years. March 15, 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S2215-0366(18)30090-7

Methods This is a 10 year follow-up study, spanning Sept 5, 2003, to Dec 30, 2014, of a randomised, double-blind trial

Department of Psychiatry

in seven centres in Hong Kong in which 178 patients with first-episode psychosis with full positive symptom (C L M Hui PhD,

resolution after at least 1 year of antipsychotic treatment were given maintenance treatment (n=89; oral quetiapine E H M Lee MBChB,

400 mg daily) or early treatment discontinuation (n=89; placebo) for 12 months. After the trial, patients received W C Chang MBChB,

S K W Chan MBBS,

naturalistic treatment. Overall this cohort of patients will have received about 3 years of treatment before entering the

E S M Chen MPhil,

follow-up phase of the study: about 2 years of maintenance treatment before study entry and 1 year of treatment in the Prof P Sham PhD,

trial. The primary outcome of this follow-up was the proportion of patients in each group (including those for whom Prof E Y H Chen MD), State Key

direct follow-up was not available) with good or poor long-term clinical outcomes at 10 years, with poor outcome Laboratory of Brain and

Cognitive Sciences (W C Chang,

defined as a composite of persistent psychotic symptoms, a requirement for clozapine treatment, or death by suicide.

S K W Chan, Prof P Sham,

The randomised trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00334035, and the follow-up study was Prof E Y H Chen), and Centre for

registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01926340. Genomic Sciences

(Prof P Sham), University of

Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special

Findings Poor 10 year clinical outcome occurred in 35 (39%) of 89 patients in the discontinuation group and 19 (21%) of

Administrative Region, China;

89 patients in the maintenance treatment group (risk ratio 1·84, 95% CI 1·15–2·96; p=0·012). Suicide was the only Department of Psychiatry,

serious adverse event that occurred in the follow-up phase (four [4%] patients in the early discontinuation group vs University of British Columbia,

two [2%] in the maintenance group). Canada (Prof W G Honer MD);

Department of Psychiatry,

United Christian Hospital,

Interpretation In patients with first-episode psychosis with a full initial response to treatment, medication continuation Hong Kong Special

for at least the first 3 years after starting treatment decreases the risk of relapse and poor long-term clinical outcome. Administrative Region, China

(E P F Pang MBChB);

Department of Psychiatry,

Funding Food and Health Bureau, Research Grants Council of Hong Kong, and AstraZeneca. Castle Peak Hospital,

Hong Kong Special

Introduction clozapine, the only medication with convincing efficacy Administrative Region, China

National clinical practice guidelines broadly agree that in treatment-resistant schizophrenia,9 but which is (S S Y Lui MBBS); Department of

Psychiatry, Tai Po Hospital,

antipsychotic medication is indicated for the acute associated with substantial side-effects. Hong Kong Special

treatment and initial maintenance of first-episode One report combines findings from an RCT of dose Administrative Region, China

psychosis. However, subsequent decisions to continue reduction in the early phase of illness with a follow-up (D W S Chung MBChB);

medication, reduce dose, or discontinue medication are study of long-term clinical outcome.10,11 In the follow-up, Department of Psychiatry,

Pamela Youde Nethersole

not well informed by available randomised controlled patients were reassessed 7 years after the start of the Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

trials (RCTs). On the one hand, naturalistic studies raise original trial. A greater proportion of patients randomly Special Administrative Region,

concerns about the long-term side-effects of maintenance assigned to the early dose-reduction group had good China (W S Yeung MBBS);

medication.1,2 On the other hand, a small number of functional outcome (24 [46%] of 52 patients) than patients Department of Psychiatry,

Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong

RCTs suggest that dose reduction or medication randomly assigned to the treatment as usual group Special Administrative Region,

discontinuation results in an increase in relapse.3 (ten [20%] of 51 patients). However, sustained medication China (R M K Ng MBChB);

However, the relation between relapse and long-term discontinuation was achieved in only 14 (22%) of Department of Psychiatry, Kwai

Chung Hospital, Hong Kong

outcome is not well studied. Some evidence suggests the 65 patients in the dose-reduction group, whereas

Special Administrative Region,

immediate consequences of relapse are limited,4 whereas 21 (32%) of 65 patients relapsed and the remainder were China (W T L Lo MBBS); and

others raise the concern that each relapse might be unable to discontinue medications, complicating the Department of Psychiatry,

associated with a poorer treatment response.5–7 Poor interpretation of the long-term outcomes.10,11 The University of Cambridge,

Cambridge, UK

clinical response is a cardinal feature of treatment- implications of early relapse were not investigated. The

(Prof P B Jones MD)

resistant psychosis8 and is the key indication for absence of adverse consequences, or perhaps even

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7 1

Articles

Correspondence to:

Dr Christy L M Hui, Department Research in context

of Psychiatry, University of

Hong Kong, Queen Mary Evidence before this study group; no difference was found in terms of severity of psychotic

Hospital, Hong Kong Special Comprehensive programmes for identifying and treating symptoms. However, in the 2 year initial phase of that trial,

Administrative Region, China first-episode psychosis have been implemented in many sustained medication discontinuation was achieved in only

christy@lmhui.com

countries to improve the health of young people and prevent 20% of participants, whereas approximately 30% relapsed and

long-term disability associated with chronic illness. the remainder were unable to discontinue medications,

Antipsychotic medication is an integral part of the treatment of complicating the interpretation of the long-term outcomes.

first-episode psychosis, and full remission of symptoms can be

Added value of this study

obtained. However, the decision of whether or not to

This study is the first double-blind, randomised trial to address

discontinue antipsychotic medication after a sustained period

the long-term consequences of the clinical decision to

of remission is a common clinical problem. In 2012,

discontinue antipsychotic medication treatment over a nearly

a systematic review of clinical guidelines available at that time

10-year follow-up period. Early discontinuation of medication

concluded that medication should continue for at least

(year 2) for patients with full remission of key positive

12–24 months after remission from first-episode schizophrenia.

symptoms of psychosis was associated with a higher risk of

For clinical guidelines published between Jan 1, 2012, and

long-term, poor clinical outcome of schizophrenia and related

Dec 31, 2017, we searched the PubMed database using the

psychotic illness than maintenance treatment. Mediation

search terms “schizophrenia” and “guideline”, and conducted a

analysis suggested that the consequences of early

manual search of the reference list of relevant guidelines found.

discontinuation for long-term poor clinical outcome were

Inclusion criteria were that the guidelines had to be developed

mediated in part through early relapse during the 12 month

using a systematic and defined process, contain

period of the randomised trial.

recommendations about pharmacological treatment for

first-episode schizophrenia, and be written in English. Implications of all available evidence

Nine relevant guidelines were found, of which five contained a Discontinuation of medication within the 3 years after starting

recommendation on the duration of medication maintenance. treatment in patients with first-episode psychosis (ie, from when

In accordance with guidelines published before 2012, these patients started maintenance treatment before study entry

five guidelines also gave a recommendation of 12–24 months. [22 months on average] to their completion of the 12 month trial

However, because of the scarcity of data concerning the period) should be carefully considered with awareness of the

long-term consequences of early medication maintenance or potential costs in terms of outcome. Patients who opt for

discontinuation, all such guidelines are ambivalent in their discontinuation should be monitored with adequate support.

recommendations for longer periods beyond 24 months. In patients with first-episode psychosis with a full initial response

The only 2 year, open-label, randomised trial of discontinuation to treatment, medication continuation for at least the first 3 years

versus maintenance treatment in first-episode psychosis after starting treatment is effective in preventing relapse and

reported outcomes at 7 years. The dose reduction group had decreasing the risk for a poor long-term clinical outcome.

better psychosocial function than the maintenance treatment

advantages of early dose-reduction, have important 10 year follow-up study of these patients to determine

implications for patient care. the effect of early medication discontinuation on long-

Many patients with first-episode psychosis have an term clinical outcomes. Maintenance treatment during

encouraging initial treatment response.12 A full the RCT was hypothesised to be less likely to be

resolution of positive symptoms of psychosis presents a associated with poor long-term outcome. We also

compelling case for medication discontinuation after an investigate the contribution of early relapse to the long-

initial maintenance period of at least 1 year, as term outcome.

recommended by many clinical practice guidelines. We

previously reported the short-term relapse outcomes of Methods

a 1 year, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Study design and participants

trial13 of early discontinuation compared with This 10 year follow-up study, spanning Sept 5, 2003, to

maintenance treatment with quetiapine 400 mg daily in Dec 30, 2014, of an RCT13 investigating the effects of early

such a group of patients. Patients were required to be discontinuation of antipsychotic medication on risk for

free of positive symptoms of psychosis and have already relapse of positive symptoms of psychosis, was designed to

had at least 1 year of antipsychotic treatment before examine the long-term consequences of early medication

randomisation. The Kaplan–Meier estimate of the discontinuation for clinical outcome. The original RCT

proportion relapsed was 79% (95% CI 68–90) in the early was a multisite study involving seven psychiatric hospitals

discontinuation group, and 41% (29–53) in the main in Hong Kong and was conducted under the Early

tenance treatment group (p<0·0001).13 After the study, Assessment Service for Young People with Psychosis. In

patients received naturalistic treatment. We now report a the original RCT,13 a higher proportion of patients in the

2 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7

Articles

placebo group had relapse at 12 months than in the randomly assigned to a group in the original RCT, giving

maintenance group.13 The study protocol is available in the them a 10 year follow-up through face-to-face interview

appendix. and obtaining chart reviews. Direct personal assessments See Online for appendix

The inclusion criteria for the RCT were a diagnosis of were done at the follow-up interview by a Master’s level

schizophrenia or non-affective psychosis (schizophreniform research assistant to obtain the primary outcome

disorder, schizoaffective disorder, brief psychotic disorder, component of persistent positive symptoms of psychosis.

or psychosis not otherwise specified) by use of criteria from We also did longitudinal chart reviews for all patients to

DSM-IV.14 Diagnostic assessments used the Chinese identify death by suicide or clozapine treatment as primary

version of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. outcome components. For any remaining patients for

Eligible patients were aged 18–65 years, had received whom death by suicide or clozapine treatment were not

antipsychotic medication continuously for at least identified as primary outcome components and for whom

12 months, were free of positive symptoms of psychosis, face-to-face interviews were not possible for obtaining

and had no history of relapse (no increase of positive data on persistent positive symptoms, we used positive

symptoms of psychosis requiring admission to hospital or symptom assessment information from the RCT to

adjustment of medication). predict outcomes.

Exclusion criteria were treatment with clozapine, depot Medication adherence was assessed with clinical

antipsychotic medication, or mood stabilising therapy interviews and pill counting during the RCT. Adherence

(lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine); poor adherence was assessed with a standardised scale during the

to treatment (missing >50% of drug, >50% missed clinic follow-up.15

visits, or a history of medication discontinuation); or a We adapted the existing dose recommendation tables

risk of suicide or violence. All patients from the original to convert the antipsychotic medications to chlorpro-

study were traced and invited to participate in the present mazine equivalents.16–18

study. Participants provided written informed consent.

Outcomes

Randomisation and masking The primary outcome of this follow-up study was the

In the original RCT, patients were randomly assigned proportion of patients in each group with good or poor

to early discontinuation (placebo) or maintenance long-term clinical outcomes at the 10 year follow-up. A poor

treatment. Details of the randomisation and masking can long-term clinical outcome was defined by persistent

be found in the original study.13 positive symptoms of psychosis, requirement for clozapine

The longitudinal review used case-note and centralised treatment (treatment-resistant schizophrenia), or death by

records of longitudinal, monthly data extracted by suicide. Positive symptoms of psychosis in the previous

research assistants masked to the randomised trial 1 month of follow-up were assessed by face-to-face interview

assignment. The first research assistant checked for using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.19 The

relevant information in the case-notes and redacted same thresholds were used as in the RCT to define presence

these, before passing to the second research assistant for of positive symptoms (delusions ≥3, conceptual

rating. disorganisation ≥4, hallucinations ≥3, suspiciousness ≥5,

or unusual thought content ≥4; appendix).13 The last

Procedures positive symptom assessment (using the Positive and

In the original RCT, patients with no residual psychotic Negative Syndrome Scale) from the randomised phase was

symptoms who already had received at least 12 months of used in our analyses for patients who could not be followed

antipsychotic treatments were randomly assigned to early up. The other two indicators of poor long-term outcome,

discontinuation (placebo) or maintenance treatment (oral initiation of clozapine for treatment resistance at any time,

quetiapine 400 mg daily; mean daily dose 411·9 mg and death by suicide at any time, were assessed through the

[SD 63·5]) for 12 months. Before starting the RCT, patients medical record review. Absence of all three of these was

had been administered antipsychotic medication for a deemed to indicate a good long-term clinical outcome.

mean of 21·9 months (SD 8·2; table 1). Participation in After the initial submission of the data analysis protocol,

the RCT ended after 1 year or if the patient relapsed or but before data collection, the primary outcome measure

withdrew for other reasons, whichever came first. Overall was modified on Dec 12, 2013, from “recovery”, an

this cohort of patients with first-episode psychosis will aggregate measure composed of clinical outcome

have received about 3 years of treatment in total before (symptoms), functioning, and hospital admission defined

entering the follow-up phase of the study: about 2 years of using the Strauss & Carpenter Scale to a composite clinical

maintenance treatment before study entry and 1 year of outcome (persistent positive symptoms, use of clozapine

treatment in the trial. After the trial, patients received for treatment resistance, or death by suicide), which was

naturalistic treatment. Specialised teams in Hong Kong defined as the primary outcome to align the present study

provided the first 3 years of care for patients after their with the primary outcome of symptom remission in the

first episode of psychosis; subsequent care was provided original RCT,13 as well as with previously available and

by general services. We attempted to trace the 178 patients subsequently published data supporting the concept that

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7 3

Articles

long-term outcome consists of several independent and the Role Functioning Scale.23 Health-related quality

dimensions.20,21 of life was assessed as an additional outcome (36-item

Secondary outcome assessments from direct ass short-form health survey).24

essment were occupational status and scores on the Serious adverse events assessed throughout the 10-year

Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale22 course were death, hospital admission, or persistent

Maintenance treatment Early discontinuation All patients

(n=89) (n=89) (n=178)

Type of disorder at final review

Schizophrenia 67 (75%) 67 (75%) 134 (75%)

Schizophreniform disorder 10 (11%) 12 (13%) 22 (12%)

Schizoaffective disorder 3 (3%) 2 (2%) 5 (3%)

Brief psychotic disorder 7 (8%) 2 (2%) 9 (5%)

Delusional disorder 1 (1%) 5 (6%) 6 (3%)

Psychosis not otherwise specified 1 (1%) 1 (1%) 2 (1%)

Substance misuse at end of naturalistic open treatment

Alcohol abuse* 2/74 (3%) 0/64 (0%) 2/138 (1%)

Other drug abuse* 0/74 (0%) 0/63 (0%) 0/137 (0%)

At start of randomised trial

Age (years) 23·5 (5·2) 24·9 (7·3) 24·2 (6·4)

Men 39 (44%) 41 (46%) 80 (45%)

Education (years) 12·0 (2·6) 11·7 (3·1) 11·8 (2·8)

Employed 62 (70%) 65 (73%) 127 (71%)

PANSS score†

Total 33·0 (4·5) 34·0 (6·3) 33·5 (5·5)

Positive 7·2 (0·6) 7·3 (0·7) 7·2 (0·6)

Negative 8·7 (2·9) 9·1 (3·6) 8·9 (3·3)

Previous open-label antipsychotic duration (months) 22·4 (8·6) 21·3 (7·8) 21·9 (8·2)

Previous antipsychotic dose at baseline (mg/day)‡ 177·4 (165·9) 125·9 (84·1) 151·6 (133·6)

Duration of untreated psychosis (days)§ 88·0 (38·0–155·0) 120·0 (40·0–378·0) 91·0 (39·8–230·8)

Randomised trial

Duration (months) 6·2 (4·8) 4·9 (4·1) 5·6 (4·5)

Longitudinal antipsychotic dose (mg/day)‡ 558·9 (31·1) 40·2 (66·1) 299·5 (265·1)

Naturalistic, open treatment

Duration (months) 105·7 (18·5) 107·0 (17·7) 106·4 (18·1)

Longitudinal antipsychotic dose (mg/day)‡ 209·0 (178·8) 245·5 (195·8) 227·3 (187·8)

End of open-treatment assessment¶

Type of medication

None 17/72 (24%) 11/66 (17%) 28/138 (20%)

Typical antipsychotic only 11/72 (15%) 10/66 (15%) 21/138 (15%)

Atypical antipsychotic only 41/72 (57%) 42/66 (64%) 83/138 (60%)

Both typical and atypical antipsychotic 3/72 (4%) 3/66 (5%) 6/138 (4%)

Antipsychotic dose at end of follow-up (mg/day)‡|| 353·8 (256·7) 356·1 (313·9) 355·0 (285·4)

Medication adherence behaviour** 3·5 (0·5) 3·6 (0·5) 3·5 (0·5)

Medication adherence attitude** 3·2 (0·6) 3·4 (0·7) 3·3 (0·6)

Data are n (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR), unless stated otherwise. PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Differences between the maintenance and discontinuation

groups were not significant. *Data were available in patients who had an end of open-treatment assessment. †PANSS measures the severity of symptoms in schizophrenia with a

range of 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. ‡The mean daily dose of each antipsychotic was converted to an equivalent dose of chlorpromazine.

§Duration of untreated psychosis was defined as the interval between onset of psychotic symptoms and first receipt of antipsychotic treatment. Duration of untreated psychosis

was assessed using the Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia, which is a standardised, semi-structured interview conducted on patients and

their close relatives within 4 months following the first episode. A review of the case notes was also done as collateral information to minimise recall bias. ¶Data are missing for

four of 142 patients with an end of open treatment assessment: 72 in the maintenance group and 66 in the early discontinuation group. ||For patients taking medication.

**The modified Medication Adherence Rating Scale was used to capture behaviours and attitude towards medication in the previous month. The first five items capture patients’

compliance behaviours in a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The remaining nine items refer to patients’ attitude towards taking medication, ranging from 1

(strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate better adherence behaviour and a more positive attitude. Data were available in patients who had completed the

end of open-treatment assessment: 60 in the maintenance treatment group and 54 in the early discontinuation group.

Table 1: Clinical and treatment characteristics of the patients

4 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7

Articles

incapacity. Each event was assessed for a relation to the early discontinuation group), we used positive

treatment during the randomised trial. Side-effects were symptom assessment information from the RCT to predict

assessed directly at the follow-up study visit, including outcomes. The inter-rater reliability for positive symptom

movement disorders assessed with three scales.25–27 ratings (intraclass correlation), between three raters on ten

Because antipsychotic drugs can cause metabolic independent cases, was 0·99 for delusions, 1·00 for

dysregulation, weight, height, fasting glucose, total conceptual disorganisation, 0·88 for hallucinations,

cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were measured. 0·99 for suspiciousness, and 0·95 for unusual thought

General side-effects were assessed using a standardised content. At 10 year follow-up, there were no significant

scale.28 differences across all variables at baseline between the

intervention groups (table 1).

Statistical analysis After completion of the RCT, patients received

For the primary outcome analysis, we used risk ratios [RR] naturalistic treatment, with antipsychotic drug treatment

and 95% CIs to compare the frequency of long-term poor

outcomes between all patients in the intervention groups

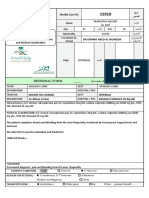

of the RCT, irrespective of whether direct follow-up was 1606 patients assessed for eligibility

available. We did sensitivity analyses to assess the use of

positive symptom assessment information from the RCT

to predict outcomes in patients for whom chart reviews 1428 excluded

1134 did not meet inclusion criteria

could not be obtained, reclassifying these remaining 384 different diagnosis

patients as either having all good outcomes or all poor 332 relapsed

284 active psychosis

outcomes. We also assessed the validity of our definitions 96 non-adherent

for good and poor clinical outcomes with a series of 38 suicidal or other risk

comparisons of symptomatic and functional measures 294 refused to participate

between the outcome groups, irrespective of assignment

during the randomised trial. We compared secondary 178 randomly assigned to a group

outcome measures using RR or independent t tests.

To determine if relapse accounted for in whole or in

part the effects of early treatment discontinuation on

long-term outcome, we did a mediation analysis using 89 assigned to maintenance 89 assigned to early

treatment and received discontinuation and received

logistic regression models and a Sobel test. We also quetiapine placebo

calculated the percentage of the total effect being

mediated by the indirect effect of relapse.29 For serious

28 discontinued trial 18 discontinued trial

adverse events, we calculated standardised mortality 15 adverse events 6 adverse events

ratios based on age–gender population mortality rate and 1 serious adverse 1 serious adverse

age–gender death by suicide rate. All statistical analyses event event

6 withdrew consent 6 withdrew consent

were done using IBM SPSS, version 24.0. 6 other 5 other

The randomised trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.

gov, number NCT00334035, and the follow-up study was

61 completed randomised phase 71 completed randomised phase

registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01926340.

Role of funding source 89 entered open-treatment and 89 entered open-treatment and

The funders of the study had no role in study design, given longitudinal chart review given longitudinal chart review

86 followed up 84 followed up

data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or 3 lost to follow-up 5 lost to follow-up

writing of the report. CLMH and EYHC had full access to

all the data in the study, and the corresponding author

had final responsibility for the decision to submit for 15 did not complete 21 did not complete

endpoint interview endpoint interview

publication. 12 declined interview 16 declined interview

assessment assessment

2 died by suicide 4 died by suicide

Results 1 unable to contact 1 unable to contact

We interviewed and obtained chart reviews for 142 (80%) of

178 patients who participated in the original RCT13

(figure 1). For the 36 remaining patients, we also did 74 completed endpoint interview 68 completed endpoint interview

longitudinal chart reviews, identifying death by suicide or

clozapine treatment as primary outcome components in 89 included in intention-to-treat 89 included in intention-to-treat

eight patients (two from the maintenance group and six analysis at 10 years analysis at 10 years

from the early discontinuation group). For the remaining

28 patients (13 from the maintenance group and 15 from Figure 1: Trial profile

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7 5

Articles

Early maintenance treatment Early discontinuation p value Effect size*

(n=89) (n=89)

Composite good primary outcome† 70 (79%) 54 (61%) 0·012 1·84 (1·15–2·96)

Composite poor primary outcome† 19 (21%) 35 (39%) ·· ··

Required clozapine 3 (3%) 8 (9%) 0·13 2·76 (0·73–10·39)

Suicide 2 (2%) 4 (4%) 0·42 2·00 (0·37–10·93)

Persistent psychosis 16 (18%) 24 (27%) 0·11 1·57 (0·90–2·74)

Delusions 8 (9%) 18 (20%) 0·030 2·36 (1·08–5·13)

Conceptual disorganisation 2 (2%) 2 (2%) 1·00 1·05 (0·15–7·27)

Hallucinations 11 (12%) 16 (18%) 0·24 1·52 (0·75–3·09)

Suspiciousness 5 (6%) 6 (7%) 0·70 1·26 (0·40–3·97)

Unusual thought content 2 (2%) 4 (4%) 0·39 2·10 (0·39–11·14)

Secondary outcomes‡

Employed 51/74 (69%) 48/68 (71%) 0·65 0·02

SOFAS§ 61·9 (9·6) 64·0 (8·9) 0·19 –0·23

RFS total¶ 21·3 (3·4) 21·5 (2·8) 0·72 –0·06

RFS work 5·4 (1·1) 5·5 (1·1) 0·73 –0·09

RFS independent living 5·7 (1·0) 5·8 (0·9) 0·72 –0·11

RFS immediate social 5·6 (1·0) 5·5 (0·9) 0·88 0·11

RFS extended social 4·7 (1·2) 4·8 (1·0) 0·64 –0·09

Other outcomes

PANSS||

Total 34·8 (5·9) 35·4 (6·6) 0·55 –0·10

Positive 7·7 (2·3) 8·4 (3·1) 0·16 –0·30

Negative 8·1 (2·1) 7·9 (1·9) 0·62 0·10

Global clinical impression**

Severity of illness 1·5 (1·1) 1·7 (1·1) 0·45 –0·13

Improvement 3·9 (0·5) 3·9 (0·7) 0·96 0

Calgary Depression Scale†† 1·1 (2·6) 1·0 (2·4) 0·87 0·04

SUMD‡‡ 1·3 (0·6) 1·3 (0·6) 0·59 0·09

SF-36:MCS§§ 50·2 (9·1) 51·0 (8·4) 0·61 –0·09

SF-36:PCS§§ 56·6 (7·6) 56·9 (6·6) 0·80 –0·04

Data are n (%) or mean (SD), unless stated otherwise. Risk ratio was used for categorical variables; hazard ratio (Cox regression) was used for time to event variables

(requiring clozapine and suicide); independent t test was used for continuous variables. SOFAS=Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. RFS=Role

Functioning Scale. PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. SUMD=Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder. SF-36=36-item short-form health survey.

MCS=mental component summary. PCS=physical component summary. *Risk ratio (95% CI) was used for the primary clinical outcome. For other measures, we used

Cramer’s V for categorical variables, Cohen’s d (normally distributed) and Rosenthal’s r (non-normally distributed) for continuous variables. Effect sizes were categorised as

small (0·2–0·4), medium (0·5–0·7), or large (≥0·8). †The primary long-term outcome measure was defined categorically, with poor outcome including any of the following:

persistent positive symptoms of psychosis, requirement for clozapine, or death by suicide; absence of all three of these was deemed to indicate a good long-term clinical

outcome. ‡Secondary outcomes from end of open treatment assessments were available for 74 patients in the early maintenance treatment group and 68 patients in the

early discontinuation group. §SOFAS assesses social and occupational functioning in patients with psychiatric illness using a range of scores from 1 to 100, with lower

scores representing impaired functioning. ¶RFS measures the functioning level in patients with psychiatric disorders, focusing on four domains: work, independent living

and self-care, immediate social network relationships, and extended social network relationships. Each domain is rated on a 7-point scale, with lower scores representing

lower functioning. ||PANSS measures the severity of symptoms in schizophrenia with a range of 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. PANSS has

a total of 30 items, with seven items on positive symptoms, seven on negative symptoms, and 16 on general psychopathology. Data were obtained from 74 patients in the

early maintenance treatment group and 68 patients in the early discontinuation group. **Global clinical impression assesses the global symptoms in patients with

psychotic disorders and is consisted of two individual scores—namely, the severity of illness (ranging from 1 [not mentally ill] to 7 [extremely ill]) and improvement

(ranging from 1 [very much improved] to 7 [very much worsened]). Data were obtained from 75 patients in the early maintenance treatment group and 68 patients in the

early discontinuation group. ††The Calgary Depression Scale for schizophrenia assesses the depressive level in schizophrenia, exclusive of other dimensions of

psychopathology. The scale consists of nine items rated on a 4-point scale from absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), to severe (4). Data were obtained from 74 patients in the

early maintenance treatment group and 67 patients in the early discontinuation group. ‡‡The abridged SUMD measures insight in schizophrenia. It consists of three items:

global awareness of mental disorders, awareness of the consequences of mental disorder, and awareness of the effects of medication; with a rating of 1 indicating

awareness, 2 indicating somewhat aware or unaware, and 3 indicating severely unaware. A global mean score was computed by summing up the three items, with higher

scores indicating poor awareness. Data were obtained from 75 patients in the early maintenance treatment group and 66 patients in the early discontinuation group.

§§SF-36 consists of 36 items on functional health and wellbeing. The scores can be classified into the MCS (scores ranging from 14 to 70; data obtained from 70 patients in

the early maintenance treatment group and 58 patients in the early discontinuation group) and the PCS (scores ranging from 21 to 74; data were obtained from 71 patients

in the early maintenance treatment group and 58 patients in the early discontinuation group). Higher scores indicate better functional health and wellbeing.

Table 2: Primary-composite, secondary, and other long-term outcome measures

6 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7

Articles

received for a mean duration of 106·4 months (SD 18·1;

A Model 1

table 1). 110 (80%) of 138 patients with complete β 0·87 (SE 0·34);

medication data at follow-up continued to take Placebo or maintenance

p=0·010

Long-term clinical

antipsychotic medication at the follow-up assessment, treatment outcome

with a mean total dose of 355·0 mg (SD 285·4) of

chlorpromazine equivalents per day. Self-reported B Model 2

adherence was high. Aside from the difference in β 1·36 (SE 0·32); p<0·0001 β 1·56 (SE 0·38); p<0·0001

Relapse of positive

exposure during the RCT, no differences in duration or symptoms of psychosis

doses of antipsychotic drug treatment between the early

discontinuation and maintenance groups over the

10 years of naturalistic treatment were reported. Similarly, Placebo or maintenance Long-term clinical

treatment outcome

clinical care received did not differ between the two β 0·43 (SE 0·37);

p=0·24

intervention groups (appendix).

Poor long-term clinical outcome occurred in 35 (39%) of Figure 2: Mediation models

89 patients randomly assigned to the discontinuation Model 1 shows the direct effect of treatment during the randomised trial on

group versus in 19 (21%) of 89 patients assigned to the long-term clinical outcome using a logistic regression analysis. Model 2 shows

the effects of testing for relapse during the randomised trial as a mediator of the

maintenance group (RR 1·84, 95% CI 1·15–2·96; effects of the randomised treatment on long-term clinical outcome. The results

p=0·012; table 2). Sensitivity analyses indicated similar of a Sobel test indicate significant mediation was present (p=0·0030).

results if analyses were limited to patients available for

direct follow-up assessment (150 of 178 patients; RR 2·05, component scores on the 36-item short-form health

1·15–3·68; p=0·016) or if the remaining 28 patients were survey measure of health-related quality of life

classified as either poor outcome (RR 1·58, 1·06–2·34; (p=0·0030).

p=0·023) or good outcome (RR 2·00, 1·10–3·63; We did a binary logistic regression analysis to assess

p=0·023). whether diagnosis (schizophrenia vs non-schizophrenia)

The initially positive, symptom-free patients recruited would affect the significant relation between treatment

in the present study represent a relevant group to answer and outcome. Treatment group was a significant factor

the clinical question of maintenance discontinuation. To related to outcome (odds ratio [OR] 0·41, 95% CI

provide an indication of the long-term outcome of a 0·21–0·80; p=0·0090): schizophrenia diagnosis was not

broader range of patients with first-episode psychosis, (OR 1·85, 0·95–3·60; p=0·070). There were no significant

we did a post-hoc analysis to compare patients with first- differences between long-term clinical outcome and the

episode psychosis whose initial treatment response was baseline measures of age (t=0·953; p=0·342), gender

less favourable than would have been included in this (χ²=1·966; p=0·161), years of education (t=–0·202;

study (ie, patients with at least 1 month of mild positive p=0·840), employment (χ²=0·070; p=0·792), medication

symptoms or who had already relapsed) with the dose taken (t=–0·814; p=0·417), or schizophrenia

maintenance and discontinuation groups (appendix).16 diagnosis (χ²=0·018; p=0·893).

The early discontinuation group in our study had a There were no significant differences in the secondary

similar high prevalence of poor long-term clinical outcomes between the early discontinuation and

outcomes (35 [39%] of 89 patients) as this initially less maintenance treatment groups (table 2).

favourable cohort (33 [49%] of 68 patients) after 10 years As previously reported, the early discontinuation group

(RR 0·80, 95% CI 0·56–1·14; p=0·21), whereas the had more relapses during the RCT.13 However, the clinical

maintenance group had fewer long-term poor clinical characteristics of relapses, including severity, duration,

outcomes (19 [21%] of 89; RR 0·43, 0·27–0·69; and resolution of positive symptoms, did not differ

p<0·0001). between the intervention groups (appendix), and these

We also did a post-hoc analysis to investigate the relapse characteristics did not differentiate between the

relation between poor long-term clinical outcome and good and poor long-term outcome groups (appendix).

measures of symptomatic and functional outcome We did a post-hoc mediation analysis of the effects of

(appendix). Our direct assessment of psychosis at the relapse and of treatment group during the RCT on risk for

outcome timepoint was a one-time face-to-face long-term poor clinical outcome (figure 2; appendix). The

assessment. The presence of psychosis (persistent total effect between treatment group and long-term

positive symptoms above threshold) was the largest clinical outcome was significant (β 0·87 [SE 0·34];

contributor to poor clinical outcome. Patients with poor p=0·010). Treatment group was a significant predictor of

long-term clinical outcomes also had more severe overall relapse during the RCT (β 1·36 [SE 0·32]; p<0·0001), and

symptom scores than patients with good long-term that relapse was a significant predictor of long-term

clinical outcomes (p<0·0001), more months with outcome (β 1·56, [SE 0·38]; p<0·0001). The direct effect

psychosis present during the entire follow-up period between treatment and outcome was no longer significant

(p=0·0030) indicated by chart review, a lower score on after controlling for the mediator of relapse (β 0·43

independent living (p=0·034), and lower mental health [SE 0·37]; p=0·24). The estimated indirect effect of relapse

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7 7

Articles

on treatment group and outcome was significant, group, and 21·0 (3·60–70·89; p<0·0001) in the early

suggesting that the increased risk for poor long-term maintenance group.

outcome associated with early discontinuation was For participants assessed directly at the 10 year

mediated through the increased risk of relapse during the follow-up, no significant differences in movement

RCT (Sobel test, t=2·97 [SE 0·71]; p=0·0030). The disorders, metabolic measures, or other side-effects were

proportion of the total effect of the treatment group on reported (table 3).

outcome that was mediated by the indirect effect of relapse

was 58% (0·1362 [indirect effect]/0·2337 [total effect]). Discussion

Death by suicide was the only serious adverse event and Early discontinuation of antipsychotics after 1 year of

did not differ between treatment intervention groups maintenance was associated with a higher risk of poor

(table 2). During the 1661 person-years of observation, long-term clinical outcome at 10 years. A post-hoc

six (3%) of 178 participants died, all by suicide analysis suggested that the adverse consequences of early

(four patients in the discontinuation group and two in the discontinuation were mediated in part through early

maintenance group; all during the follow-up period). The relapse during the 1 year period following medication

crude mortality rate was 3·6 deaths per 1000 person- discontinuation.

years. Compared with age-matched and gender-matched This study addresses a pressing question (medication

Hong Kong population data, the standardised mortality discontinuation) in an important population (patients

ratio was 5·64 (95% CI 2·29–11·73; p<0·0001). The with first-episode psychosis who responded well to

suicide-specific standardised mortality ratio was treatment with no residual psychotic symptoms), in a

31·82 (12·90–179·13; p<0·0001) in the whole population, context that goes beyond available guidelines and data

40·4 (12·84–97·46; p<0·0001) in the early discontinuation (broadly suggesting at least 1 year of treatment).

Early maintenance treatment Early discontinuation (n=89) p value

(n=89)

n Measure n Measure

Serious adverse event

Death 89 2 (2%) 89 4 (4%) 0·42

Number of admissions to hospital following randomisation 89 1·0 (0·0–2·0) 89 0·0 (0·0–2·0) 0·78

Duration of hospital admission following randomisation (days)† 89 55·0 (23·5–106·0) 89 71·0 (23·5–193·0) 0·38

Side-effects of medication

Simpson-Angus Scale‡ 67 0 (0·0) 63 0·0 (0·1) 0·32

Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale§ 66 0·0 (0·1) 63 0·3 (1·5) 0·13

Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale¶ 66 0·3 (1·0) 63 0·3 (1·2) 0·82

Weight (kg) 71 71·7 (16·9) 60 71·6 (14·2) 0·99

Body-mass index|| 71 26·4 (5·6) 60 26·1 (5·0) 0·73

Fasting glucose (mg/dL)** 65 97·3 (28·8) 59 100·9 (37·8) 0·57

Cholesterol total (mg/dL)†† 64 189·5 (34·8) 57 189·5 (36·7) 0·88

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) 60 46·4 (11·6) 55 50·3 (11·6) 0·28

UKU Side-Effects Rating Scale‡‡ (≥mild)

Sleepiness or sedation 59 22 (37%) 60 25 (42%) 0·40

Failing memory 59 15 (25%) 60 11 (18%) 0·78

Weight gain 59 20 (34%) 60 15 (25%) 0·17

UKU Global Side-Effects (≥mild)

Assessed by patient 59 21 (36%) 60 15 (25%) 0·20

Assessed by physician 59 12 (20%) 60 13 (22%) 0·65

Data are n (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR), unless stated otherwise. UKU=Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser. *Other adverse events and side-effects during the randomised trial

phase were reported in detail previously. Risk ratio was used for categorical variables; independent t tests were used for continuous variables. †Reported for 89 patients who were

admitted to hospital only: 45 in the early maintenance treatment group and 44 in the early discontinuation group. ‡The Simpson-Angus Scale ranges from 0 (normal) to

4 (severe), with a higher score indicating more severe extrapyramidal side-effects. §The Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale ranges from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating

more severe tardive dyskinesia. ¶The Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale ranges from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more severe akathisia. ||The body-mass index is the weight

in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres. **To convert values for blood glucose to millimoles per litre, multiply by 0·05551. ††To convert values for total

cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol to millimoles per litre, multiply by 0·02586. ‡‡The numbers and percentages of patients who had any of 42 side-effects scored

as 1 (mild) or higher according to the UKU, a side-effects rating scale. According to this scale, each item is rated from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe side-effects.

Movement-disorder side-effects are not shown because these were assessed according to more detailed scales above. Only side-effects that occurred in at least 20% of the

patients in a treatment group are reported. For all side-effects, there were no significant differences between the groups (all p values >0·05).

Table 3: Serious adverse events, movement disorders, metabolic measures, and general side-effects*

8 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7

Articles

Notably, the clinical outcome started to diverge in the might be course-modifying. In the group of patients

cohorts included in this study from the very first episode studied in this Article, we found no evidence that any

of psychosis. Some patients did not achieve resolution of specific clinical features of the relapse such as severity,

psychotic symptoms30 and some had relapsed within need for hospital admission, or time to resolution

months.5 In the real-world setting, medication contributed to long-term outcome.

discontinuation is generally not recommended for these The main limitation of our study is the extent to which

groups.22,31 For patients who attained symptom resolution, conclusions can be generalised. A low proportion of

present guidelines suggest maintenance treatment for at the patients with first-episode psychosis studied in

least 1 year,22,31 but do not offer more specific guidance for Hong Kong had comorbid substance abuse and

after this point because of the paucity of long-term consequently the cohort would be likely to have more

outcome studies. homogeneity than an equivalent cohort studied

In an open-label study,10,11 Wunderink and colleagues elsewhere.

randomly assigned a broad range of patients with early We focused on patients with complete symptom

psychosis (including those with persistent psychotic resolution after the first episode because in practice this

symptoms corresponding to a score of moderate is the group in whom an understandable expectation

[rating of 4] using the Positive and Negative Syndrome about medication discontinuation arose. To put the

Scale), and found a dose reduction or discontinuation present findings in a wider first-episode psychosis

strategy might be beneficial to the long-term functional context, we compared data from the present RCT cohort

outcome. However, the issue of medication with a cohort of patients with less satisfactory initial

discontinuation was not addressed directly because outcome (thus excluded from the RCT). Patients with

discontinuation was implemented in only half of the early symptom resolution randomly assigned to

patients. In that study, only 45% of patients had a maintenance in our study fared best. Patients with

diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 35% had comorbid early symptom resolution randomly assigned to

substance dependence or abuse. The patients differed discontinuation had less favourable long-term outcome,

from the present study in having only 6 months of similar to patients without early symptom resolution.

maintenance treatment at entry. A high proportion of our patients were employed

In our double-blind RCT,13 we focused on patients (71% during the RCT and 70% at follow-up), which is

with good initial outcome (no residual psychotic different from cohorts in other countries. The high

symptoms) and investigated the effect of discontinuation employment might be related to the fact that we

because this is generally consistent with patients’ specifically targeted a highly responsive cohort of patients

preferences. Our patients had no comorbid substance with first-episode psychosis, in addition to the cultural

abuse, most fulfilled the diagnosis of schizophrenia expectation among Chinese patients to participate in the

(75%), and all had completed at least 1 year of workforce like other people in the community.

maintenance treatment. The present study addresses Non-adherence ratings based on pill counting during

the 10 year outcome of this cohort. Our primary the RCT and patients’ self-reports at follow-up might

outcome was clinical (persistent positive symptoms, overestimate true adherence. Owing to the more

need for clozapine, and death by suicide), aligned with collectivistic culture, with more family involvement in

previous recommendations,7 suggesting that persistent facilitating medication adherence, non-adherence in

positive symptoms were the largest contributor to poor Hong Kong was lower than in other countries.

long-term outcome.32,33 Notably, our study excluded Additionally, the original RCT excluded patients who

patients who were non-responsive to treatment from required depot medication to ensure adherence because

the outset,34,35 and some of the included patients the design involved randomisation to an oral medication

developed a poor response later, after initially good or placebo. Future studies designed to use depot

responses. This late poor response necessitated medication, and depot placebo, would help address

clozapine treatment in some patients, with its these important considerations concerning adherence.

associated side-effects and risks. A possible consequence of using a standardised

Mediation analysis supported early relapse as a mediator maintenance treatment (quetiapine) in the RCT could be

of the long-term effect of treatment discontinuation. This some early relapses in the maintenance group related to

finding indicates that relapse might itself alter the course switching medication.

of a psychotic illness. In this regard, it is important to Finally, although our study is the largest yet reported

recognise that 80% of patients in both intervention groups of an RCT testing the effects of early medication

eventually had a relapse during the 10 year period. discontinuation, we cannot be certain of the possible

However, relapse early in the second to third year during effects of schizophrenia versus other diagnoses of

the course of illness, following treatment discontinuation, psychotic illness on the effects of early relapse on long

seemed to carry more adverse implications for long-term term outcome, investigation of which will require larger

outcome, raising the suggestion that there might be a studies with careful documentation of diagnoses over

time window or critical period during which a relapse time.

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7 9

Articles

A 2017 review and commentary highlight the increasing 2 Goff DC, Falkai P, Fleischhacker WW, et al. The long-term effects of

interest in the long-term consequences of antipsychotic antipsychotic medication on clinical course in schizophrenia.

Am J Psychiatry 2017; 174: 840–49.

drug treatment.2,36 One consequence of long-term 3 Zipursky RB, Menezes NM, Streiner DL. Risk of symptom

antipsychotic medications in animals, and possibly in recurrence with medication discontinuation in first-episode

some patients, is the development over time of dopamine psychosis: a systematic review. Schizophrenia Res 2014;

152: 408–14.

receptor hypersensitivity, or a so-called supersensitivity 4 Gitlin M, Nuechterlein K, Subotnik KL, et al. Clinical outcome

psychosis. Characteristics of this syndrome are a severe following neuroleptic discontinuation in patients with remitted

rebound of symptom severity after switching or recent-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1835–42.

5 Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, Harvey BH. The nature of relapse in

discontinuing medication, and the development of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13: 50.

tardive dyskinesia. The prevalence of supersensitivity 6 Wiersma D, Nienhuis FJ, Slooff CJ, Giel R. Natural course of

psychosis is uncertain, and although individual patients schizophrenic disorders: a 15-year followup of a Dutch incidence

cohort. Schizophrenia Bull 1998; 24: 75–85.

might exhibit this pattern of symptomatology, substantial

7 Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Koreen A, et al. Psychobiologic correlates

evidence suggests that the more usual pattern of of treatment response in schizophrenia.

response or changes in response to maintenance Neuropsychopharmacol 1996; 14 (suppl 3): 13S–21S.

antipsychotic medications over time is not consistent 8 Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, et al. Treatment-resistant

schizophrenia: treatment response and resistance in psychosis

with the supersensitivity phenomena.2,36 Our study was (TRRIP) working group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and

not designed to investigate the possibility of terminology. Am J Psychiatry 2017; 174: 216–29.

supersensitivity psychosis in detail. 9 Kane JM. Treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 1987;

13: 133–56.

In summary, our data are relevant to patients who have

10 Wunderink L, Nienhuis FJ, Sytema S, Slooff CJ, Knegtering R,

symptomatic resolution following 1 year’s treatment of Wiersma D. Guided discontinuation versus maintenance treatment

first-episode psychosis (predominantly schizophrenia) in remitted first-episode psychosis: relapse rates and functional

outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 654–61.

and wish to consider medication discontinuation after a

11 Wunderink L, Nieboer RM, Wiersma D, Sytema S, Nienhuis FJ.

period of maintenance. The data suggest that an Recovery in remitted first-episode psychosis at 7 years of follow-up

awareness of the increased risk for poor long-term of an early dose reduction/discontinuation or maintenance

outcome, in addition to the risk for relapse in the short- treatment strategy: long-term follow-up of a 2-year randomized

clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 913–20.

term, must be taken into consideration in this decision. 12 Zhu Y, Li C, Huhn M, et al. How well do patients with a first

In patients with first-episode psychosis with a full initial episode of schizophrenia respond to antipsychotics: a systematic

response to treatment, medication continuation for at review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;

27: 835–44.

least the first 3 years after starting treatment (about 13 Chen EYH, Hui CLM, Lam MML, et al. Maintenance treatment

2 years of maintenance treatment before study entry and with quetiapine versus discontinuation after one year of treatment

1 year of treatment in the trial) is effective in preventing in patients with remitted first episode psychosis: randomised

controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 341: c4024.

relapse and decreasing the risk for a poor long-term 14 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual

outcome. of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Washington: American Psychiatric

Association, 1994.

Contributors

15 Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a

CLMH, WGH, and EYHC designed the study, analysed the data, and

new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses.

wrote and revised the Article. CLMH, EHML, WCC, SKWC, and EYHC

Schizophrenia Res 2000; 42: 241–47.

obtained funding and supervised the study. ESMC collected and

16 American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the

analysed the data and revised the Article. CLMH, EHML, WCC, SKWC,

treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd edn. Washington, DC:

and EYHC collected the data and revised the Article. EPFP, SSYL, American Psychiatric Association, 2004.

DWSC, WSY, RMKN, WTLL, and PBJ revised the Article. PS analysed

17 Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical

the data and revised the Article. CLMH and EYHC are guarantors. antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64: 663–67.

Declaration of interests 18 Taylor D, Paton C, Kerwin R. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines,

WGH has received consultation fees from Otsuka, Lundbeck, 10th edn. UK: CRC press, 2009.

AphaSights, and Eli Lilly. WTLL has participated as a paid consultant for 19 Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome

Jansen. EYHC has received speaker honoraria from Otsuka and DSK scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 1987; 13: 261–76.

BioPharma, received research funding from Otsuka, participated in paid 20 Chan SKW, So HC, Hui CLM, et al. 10-year outcome study of an

advisory boards for Jansen and DSK BioPharma, and received funding to early intervention program for psychosis compared with standard

attend conferences from Otsuka and DSK BioPharma; EYHC reports no care service. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 1181–93.

other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the 21 Revier J, Reininghaus U, Dutta R, et al. Ten-year outcomes of

submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests. first-episode psychoses in the MRC AESOP-10 study.

J Nerv Ment Dis 2015; 203: 379–86.

Acknowledgments 22 Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV:

The randomised-treatment phase of the study was supported by the a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry 1992;

Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (7655/05M) and AstraZeneca 149: 1148–56.

(investigator-initiated study award). AstraZeneca prepared the quetiapine 23 Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, Leavitt N. Assessing levels of

and the placebo, and packaged the study medications according to the adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale.

randomisation schedule. The follow-up study was supported by the Food Community Ment Health J 1993; 29: 119–31.

and Health Bureau of Hong Kong (10111101). WGH was supported by 24 Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health

the Jack Bell Chair in Schizophrenia. summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute,

New England Medical Center, 1994.

References

25 Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side

1 Correll C. Acute and long-term adverse effects of antipsychotics.

effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212: 11–19.

CNS Spectrums 2007; 12: 10–14.

10 www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7

Articles

26 Guy W. Abnormal involuntary movements scale (AIMS). 32 Jordan G, Lutgens D, Joober R, Lepage M, Iyer SN, Malla A.

In: Guy W, ed. The ECDEU assessment manual for The relative contribution of cognition and symptomatic remission

psychopharmacology, revised edn. Washington, DC: Department of to functional outcome following treatment of a first episode of

Health, Education and Welfare, National Institute of Mental Health, psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2014; 75: e566–72.

1976: 534–37. 33 Haro JM, Altamura C, Corral R, et al. Understanding the impact of

27 Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. persistent symptoms in schizophrenia: Cross-sectional findings

Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154: 672–76. from the Pattern study. Schizophrenia Res 2015; 169: 234–40.

28 Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU 34 Meltzer H. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia—the role of clozapine.

side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for Curr Med Res Opin 1997; 14: 1–20.

psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in 35 Lally J, Ajnakina O, Di Forti M, et al. Two distinct patterns of

neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1987; treatment resistance: clinical predictors of treatment resistance in

334: 1–100. first-episode schizophrenia spectrum psychoses. Psychol Med 2016;

29 MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in 46: 3231–40.

prevention studies. Eval Rev 1993; 17: 144–58. 36 Leucht S, Davis JM. Do antipsychotic drugs lose their efficacy for

30 Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Medori R et al. Remission in early relapse prevention over time? Br J Psychiatry 2017; 211: 127–29.

psychosis: rates, predictors, and clinical and functional outcome

correlates. Schizophrenia Res 2007; 89: 129–39.

31 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical

Practice Guidelines Team for the Treatment of Schizophrenia and

Related Disorders. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of

Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of

schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust NZJ Psychiatry 2005;

39: 1–30.

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online March 15, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30090-7 11

You might also like

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in Clozapine-Resistant Schizophrenia (FOCUS) : An Assessor-Blinded, Randomised Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesCognitive Behavioural Therapy in Clozapine-Resistant Schizophrenia (FOCUS) : An Assessor-Blinded, Randomised Controlled TrialRabiatul AdawiyahNo ratings yet

- Tapering Clonazepam in Patients With Panic Disorder After at Least 3 Years of Treatment.Document4 pagesTapering Clonazepam in Patients With Panic Disorder After at Least 3 Years of Treatment.Anonymous mxuaruDNo ratings yet

- Pituitary Tumors: A Clinical CasebookFrom EverandPituitary Tumors: A Clinical CasebookLisa B. NachtigallNo ratings yet

- Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Outcome Identification Planning Intervention Rationale Evaluation Subjective Data: Short Term: IndependentDocument2 pagesAssessment Nursing Diagnosis Outcome Identification Planning Intervention Rationale Evaluation Subjective Data: Short Term: IndependentDimple Castañeto Callo100% (1)

- Jurnal JiwaDocument6 pagesJurnal JiwaoldDEUSNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Electroacupuncture and ElectroconDocument9 pagesEffectiveness of Electroacupuncture and ElectroconKrithika Devi CNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument11 pagesArticles: Backgroundyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- Acute and Preventive Pharmacologic Treatment of Cluster HeadacheDocument12 pagesAcute and Preventive Pharmacologic Treatment of Cluster Headachelusi jelitaNo ratings yet

- DemenciaDocument8 pagesDemenciajuby30No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673623020330 Main 2Document12 pages1 s2.0 S0140673623020330 Main 2Uriel EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Electroconvulsive TherapyDocument10 pagesElectroconvulsive TherapyYasinNo ratings yet

- IJPsy 45 26 PDFDocument4 pagesIJPsy 45 26 PDFanettewillNo ratings yet

- Algorithm-Based Pharmacotherapy For First-Episode Schizophrenia Involuntarily Hospitalized: A Retrospective Analysis of Real-World PracticeDocument8 pagesAlgorithm-Based Pharmacotherapy For First-Episode Schizophrenia Involuntarily Hospitalized: A Retrospective Analysis of Real-World PracticerischaNo ratings yet

- Short-Term and Long-Term Evaluation of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in The Treatment of Panic Disorder: Fluoxetine Vs CitalopramDocument6 pagesShort-Term and Long-Term Evaluation of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in The Treatment of Panic Disorder: Fluoxetine Vs CitalopramBakhita MaryamNo ratings yet

- CTS PDFDocument6 pagesCTS PDFBiola DwikoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Affective DisordersDocument8 pagesJournal of Affective DisordersDeni SetyawanNo ratings yet

- 2013 Burmester (TOFA Vs PLA)Document10 pages2013 Burmester (TOFA Vs PLA)Marcel JinihNo ratings yet

- 60 - Minocycline Combination Therapy Withfluvoxaminein Moderate-To-Severe Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomized TrialDocument10 pages60 - Minocycline Combination Therapy Withfluvoxaminein Moderate-To-Severe Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomized TrialPaula CantalapiedraNo ratings yet

- Lancet Duration of DAPT After SCA (Article Onlinefirst)Document11 pagesLancet Duration of DAPT After SCA (Article Onlinefirst)Mr. LNo ratings yet

- Furukawa 2016Document8 pagesFurukawa 2016Luis CsrNo ratings yet

- Pitman 2002 Biological-PsychiatryDocument4 pagesPitman 2002 Biological-PsychiatryQwerty QwertyNo ratings yet

- Pilot Study of Sphenopalatine Injection of Onabotulinumtoxina For The Treatment of Intractable Chronic Cluster HeadacheDocument7 pagesPilot Study of Sphenopalatine Injection of Onabotulinumtoxina For The Treatment of Intractable Chronic Cluster HeadacheadriantiariNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Nefazodone, The Cog Behav Sys of Psychotherapy TX DepressionDocument9 pagesComparison of Nefazodone, The Cog Behav Sys of Psychotherapy TX DepressionCarolina BerríosNo ratings yet

- Artigo InglesDocument11 pagesArtigo InglesEllen AndradeNo ratings yet

- Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptor Agonist and Peripheral Antagonist For Schizophrenia (2021)Document10 pagesMuscarinic Cholinergic Receptor Agonist and Peripheral Antagonist For Schizophrenia (2021)ShadeLRKNo ratings yet

- Journal - Effectiveness of Electroconvulsive Therapy in Patients With Treatment Resistant SchizophreniaDocument22 pagesJournal - Effectiveness of Electroconvulsive Therapy in Patients With Treatment Resistant SchizophreniaAntikka PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Music Therapy Derived From The Five Elements in Traditional Chinese Medicine On Post-Stroke DepressionDocument6 pagesEffect of Music Therapy Derived From The Five Elements in Traditional Chinese Medicine On Post-Stroke DepressionwindapuspitasalimNo ratings yet

- Clozapine For Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesClozapine For Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic ReviewAsepDarussalamNo ratings yet

- Cuma Abstraknya Aja: TTG Risperidone: Stroke Therapy TreatmentsDocument6 pagesCuma Abstraknya Aja: TTG Risperidone: Stroke Therapy TreatmentsChandz ChanDra ErryandariNo ratings yet

- Jama Yang 2023 Oi 230112 1697473261.42652Document12 pagesJama Yang 2023 Oi 230112 1697473261.42652adol1018No ratings yet

- Ect Skizo ResistenDocument28 pagesEct Skizo ResistenZulvikar UmasangadjiNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument13 pagesArticles: BackgroundBianca AlinaNo ratings yet

- Hongos Contra La MigrañaDocument10 pagesHongos Contra La MigrañaRamón Vargas CortezNo ratings yet

- Critical Review of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy in The Treatment of SchizophreniaDocument18 pagesCritical Review of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy in The Treatment of SchizophreniaFatkha RizqianaNo ratings yet

- Articles: B AckgroundDocument8 pagesArticles: B AckgroundNurul Kamilah SadliNo ratings yet

- 08 Art ORIGINALE Fazzari1-DikonversiDocument3 pages08 Art ORIGINALE Fazzari1-DikonversiAkhsay ChandraNo ratings yet

- Clozapine For Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesClozapine For Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic ReviewAsepDarussalamNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Electroacupuncture and Body Acupuncture On Gastrocnemius Muscle Tone in Children With Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Single Blinded, Randomized Controlled Pilot TrialDocument6 pagesComparison of Electroacupuncture and Body Acupuncture On Gastrocnemius Muscle Tone in Children With Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Single Blinded, Randomized Controlled Pilot TrialrezteevicNo ratings yet

- Studyprotocol Open Access: Begemann Et Al. Trials (2020) 21:147Document19 pagesStudyprotocol Open Access: Begemann Et Al. Trials (2020) 21:147Priti BhosleNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading SarafDocument10 pagesJournal Reading SarafRifa RoazahNo ratings yet

- Current Treatments of The Anxiety Disorders in Adults: James C. BallengerDocument16 pagesCurrent Treatments of The Anxiety Disorders in Adults: James C. BallengerElizaIancuNo ratings yet

- Acupuncture For Primary Fibromyalgia: Study Protocol of A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesAcupuncture For Primary Fibromyalgia: Study Protocol of A Randomized Controlled TrialSILVIA ROSARIO CHALCO MENDOZANo ratings yet

- Critical Review of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy in The Treatment of SchizophreniaDocument11 pagesCritical Review of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy in The Treatment of SchizophreniaRagabi RezaNo ratings yet

- Do Analgesics Improve Functioning in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain? An Explorative Triple-Blinded RCTDocument7 pagesDo Analgesics Improve Functioning in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain? An Explorative Triple-Blinded RCTMiki DoktorNo ratings yet

- PIIS2215036623002584Document12 pagesPIIS2215036623002584Dr. Nivas SaminathanNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Transitional Palliative Care Model On Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure - A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesEffects of A Transitional Palliative Care Model On Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure - A Randomised Controlled TrialcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Does Cognitive Behavioural Therapy InfluenceDocument11 pagesDoes Cognitive Behavioural Therapy InfluenceRido Prama Eled PatopangNo ratings yet

- RCT - Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - 2017Document10 pagesRCT - Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - 2017RayssaNo ratings yet

- ZhangDocument5 pagesZhangLi-Hao Steven ChengNo ratings yet

- Sun 2016Document12 pagesSun 2016trifamonika23No ratings yet

- Effects of A Transitional Palliative Care Model On Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure: A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesEffects of A Transitional Palliative Care Model On Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure: A Randomised Controlled TrialNujaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy Relapse Prevention in Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesPharmacotherapy Relapse Prevention in Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trialyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- Paper 2Document5 pagesPaper 2fernanda cornejoNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Effects of The Concomitant Use of Memantine With Cholinesterase Inhibition in Alzheimer DiseaseDocument10 pagesLong-Term Effects of The Concomitant Use of Memantine With Cholinesterase Inhibition in Alzheimer DiseaseDewi SariNo ratings yet

- Manuscrip 2 PDFDocument41 pagesManuscrip 2 PDFayu purnamaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1876201822001307 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S1876201822001307 Maincherish60126No ratings yet

- Predictors of Relapse in Chinese Schizophrenia Patients: A Prospective, Multi-Center StudyDocument7 pagesPredictors of Relapse in Chinese Schizophrenia Patients: A Prospective, Multi-Center StudyDhienWhieNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673613622461 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0140673613622461 MainFrancisco Javier RamosNo ratings yet

- h1n1 JurnalDocument9 pagesh1n1 JurnalAnonymous fbvYMXNo ratings yet

- Paroxetine, Cognitive Therapy or Their Combination in The Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder With and Without Avoidant Personality Disorder: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument11 pagesParoxetine, Cognitive Therapy or Their Combination in The Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder With and Without Avoidant Personality Disorder: A Randomized Clinical TrialAdm Foto MahniteseNo ratings yet

- What Works in Therapy?Document12 pagesWhat Works in Therapy?Ariel PollakNo ratings yet

- Master of Hospital AdministrationDocument3 pagesMaster of Hospital AdministrationDEEPESH RAINo ratings yet

- AEFA9Document3 pagesAEFA9Aaser AhmedNo ratings yet

- Jonas Salk BiographyDocument3 pagesJonas Salk BiographyhapsNo ratings yet

- Job Description of PWCDocument4 pagesJob Description of PWCYang WangNo ratings yet

- Sabrina BroughtonDocument1 pageSabrina Broughtonapi-539874337No ratings yet

- Advances in The Management of Persistent Pain.110Document5 pagesAdvances in The Management of Persistent Pain.110EmaDiaconuNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Leprosy ControlDocument16 pagesEvolution of Leprosy ControlSanthosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Porth Pathophysiology Concepts of Altered Health States 1st Canadian Edition HannonDocument15 pagesTest Bank For Porth Pathophysiology Concepts of Altered Health States 1st Canadian Edition Hannonuncapepais16614100% (44)

- Coversyl Plus Launch Plan (Revised)Document37 pagesCoversyl Plus Launch Plan (Revised)Shauket HossainNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Dehydration of NewbornDocument7 pagesJurnal Dehydration of NewbornRSU Aisyiyah PadangNo ratings yet

- 2018 Nhis MLDocument23 pages2018 Nhis MLYoussef KaidNo ratings yet

- Referral FormDocument2 pagesReferral Formraad_alghamdi_1No ratings yet

- Lesson 7 - Communication and Culture or ClilDocument26 pagesLesson 7 - Communication and Culture or Clilphamngocduc050707No ratings yet

- 3097693951-Guidelines For Setting Up of 10 Bedded AYUSH HospitalDocument10 pages3097693951-Guidelines For Setting Up of 10 Bedded AYUSH Hospitalwk100% (1)

- Global Spending On Health: A World in TransitionDocument68 pagesGlobal Spending On Health: A World in TransitionKamalakar KaramchetiNo ratings yet

- Trial of ScarDocument12 pagesTrial of Scarnyangara50% (2)

- The FIM Instrument Background Structure and UsefulnessDocument31 pagesThe FIM Instrument Background Structure and UsefulnessAni Fran SolarNo ratings yet

- Management of Dental Emergencies in Children and Adolescents - 2019 - Neuhaus PDFDocument296 pagesManagement of Dental Emergencies in Children and Adolescents - 2019 - Neuhaus PDFFran GidiNo ratings yet

- Group 4Document19 pagesGroup 4SAGARGAONKAR386079No ratings yet

- Future Challenges and Objectives For Pda in Asiapac: Connecting People, Science and RegulationDocument11 pagesFuture Challenges and Objectives For Pda in Asiapac: Connecting People, Science and RegulationhuykhiemNo ratings yet

- 4NCPDocument2 pages4NCPSoleil AuNo ratings yet

- Laporan SGD LBM 1 Blok Emergency Dan Medicolegal: Disusun Oleh: Kelompok 3 AnggotaDocument3 pagesLaporan SGD LBM 1 Blok Emergency Dan Medicolegal: Disusun Oleh: Kelompok 3 AnggotaYann BhieNo ratings yet

- Document 12Document1 pageDocument 12selbal0% (1)

- Pharmacy Assistant's CompetencyDocument8 pagesPharmacy Assistant's CompetencyFelipe De OcaNo ratings yet

- Built With Science 5 Minute Daily Stretch RoutineDocument12 pagesBuilt With Science 5 Minute Daily Stretch Routinelisa martinNo ratings yet

- UniKl 171114 PDFDocument1 pageUniKl 171114 PDFCokelat KingNo ratings yet

- TIGER Initiative Informatics DefinitionsDocument9 pagesTIGER Initiative Informatics DefinitionslaggantigganNo ratings yet