Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antiplatelet Drugs

Uploaded by

Ahmad DzakyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antiplatelet Drugs

Uploaded by

Ahmad DzakyCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2019; 00: 1–5

doi 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0154

Antiplatelet Drugs: A Review of Pharmacology and

the Perioperative Management of patients in Oral

and Maxillofacial Surgery

H Mahmood1, I Siddique2, A McKechnie3

1

Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Clinical Dentistry, University of Sheffield,

Sheffield, UK

2

Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford, UK

3

Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Leeds Dental Institute, Leeds, UK

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION An increasing number of patients are taking oral antiplatelet agents. As a result, there is an important patient

safety concern in relation to the potential risk of bleeding complications following major oral and maxillofacial surgery. Surgeons

are increasingly likely to be faced with a dilemma of either continuing antiplatelet therapy and risking serious haemorrhage or

withholding therapy and risking fatal thromboembolic complications. While there are national recommendations for patients

taking oral antiplatelet drugs undergoing invasive minor oral surgery, there are still no evidence-based guidelines for the

management of these patients undergoing major oral and maxillofacial surgery.

METHODS MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched to retrieve all relevant articles published to 31 December 2017.

FINDINGS A brief outline of the commonly used antiplatelet agents including their pharmacology and therapeutic indications is

discussed, together with the haemorrhagic and thromboembolic risks of continuing or altering the antiplatelet regimen in the

perioperative period. Finally, a protocol for the management of oral and maxillofacial patients on antiplatelet agents is

presented.

CONCLUSIONS Most current evidence to guide decision making is based upon non-randomised observational studies, which

attempts to provide the safest possible management of patients on antiplatelet therapy. Large randomised clinical trials are

lacking.

KEYWORDS

Aspirin – Clopidogrel – Antiplatelets – Perioperative – Haemorrhage – Thrombosis

Accepted 8 September 2019

CORRESPONDENCE TO

Hanya Mahmood, E: hanya.mahmood@nhs.net

Introduction antiplatelet therapy undergoing major oral and maxillofa-

cial surgery where the risk of bleeding complications is

An increasing number of patients are taking oral

potentially greater.

antiplatelet agents for primary or secondary prevention of

vascular thrombosis. Surgeons are increasingly likely to be

faced with the dilemma of continuing or omitting

antiplatelet therapy prior to major surgery.1 The potential Methods

risk of continuing therapy could result in severe MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched to

haemorrhage, whereas the potential risk of omitting retrieve all relevant articles published to 31 December

therapy may result in fatal thromboembolic complications. 2017. Linked search terms included ‘oral’, ‘maxillofacial’,

Due to the challenges faced when dealing with this cohort ‘surgery’, ‘antiplatelets’ and ‘anticoagulants’, together with

of patients, the need for evidence-based guidelines is generic and brand names for all commonly used

essential to address this important patient safety concern. antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel. General consensus

Although there are national guidelines for patients was used to agree upon discrepancies in article selection

taking antiplatelet drugs undergoing invasive minor oral otherwise our second author (IS) made the final decision

surgery procedures, these are based on consensus and to resolve any disagreement between the authors. Only

expert opinions alone.2 There are no evidence-based articles in English language were included in our review.

guidelines for the perioperative management of patients on

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2019; 000: 1–5 1

MAHMOOD SIDDIQUE MCKECHNIE ANTIPLATELET DRUGS: A REVIEW OF PHARMACOLOGY AND

THE PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS IN ORAL

AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY

Findings who have been medically treated and eligible for

thrombolytic therapy. This combination is also licensed

This is the first review to propose recommendations based following insertion of drug-eluting and bare-metal stents.10

upon the current literature and scientific evidence. A brief Aspirin and clopidogrel block complementary pathways in

outline of the commonly used antiplatelet agents including platelet aggregation and therefore have synergistic effects

their pharmacology and therapeutic indications is when used in combination.11

discussed along with the haemorrhagic and thromboem-

bolic risks of continuing or altering the antiplatelet Dipyridamole

regimen in the perioperative period. Finally, a protocol for Dipyridamole is used in combination with oral

the management of oral and maxillofacial patients on anticoagulation for prophylaxis of prosthetic heart valve

antiplatelet agents is presented. thromboembolic events.12 It inhibits cellular adenosine

uptake leading to its greater availability for binding to the

Effect of antiplatelet agents on clotting and bleeding time adenosine receptor on platelets. It also inhibits the enzyme

After a vascular injury, platelets aggregate to plug the cyclic guanine monophosphate phosphodiesterase.8

defect at the earliest stage of haemostasis. However, they Dipyridamole has less antiplatelet activity compared with

are also fundamental in the pathological process of arterial aspirin and ADP receptor blockers and its action on

thrombosis leading to coronary and cerebrovascular phosphodiesterase ceases to exist within 24 hours of

events.3 Antiplatelet agents reduce the ability of blood to stopping the drug.13

clot or coagulate by reversibly or irreversibly inhibiting

platelet activation and aggregation necessary for the initial Aspirin and dipyridamole

platelet plug in primary haemostasis. Platelet function is Aspirin and dipyridamole as a combined drug is licensed

quantified using the cutaneous bleeding time with a for secondary prevention of cerebrovascular disease and

normal range of 2–10 minutes,3 although there is no transient ischaemic attacks but does not appear to increase

reliable correlation between bleeding time and the rate of the incidence of adverse bleeding events compared with

surgical bleeding complications.4 individual antiplatelet agents.14

Antiplatelet agents and their therapeutic indications Prasugrel and ticagrelor

Antiplatelet agents are prescribed for patients after an Prasugrel and ticagrelor are new generation anti-platelet

acute coronary syndrome or coronary stent placement. drugs. They are currently only licensed for use in

Damaged endothelium and stents act as unstable plaques. combination with aspirin for the secondary prevention of

A bare-metal stent is covered by endothelium within 12 cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.15,16

weeks,5 whereas a drug-eluting stent has a slower Prasugrel has irreversible antiplatelet activity by binding

endothelialisation rate of 13% at three months and 56% at to P2Y12 ADP receptors.15 It is more effective than

three years.6 Thus, the recommended duration of clopidogrel in preventing stent thrombosis but has an

antiplatelet therapy for a bare-metal stent is a minimum of increased rate of serious bleeding (1.4% vs 0.9% in the

6 weeks and a minimum of 12 months for a drug-eluting clopidogrel group) and fatal bleeding (0.4% vs 0.1%).16

stent.7 Ticagrelor is an allosteric antagonist which reversibly

blocks ADP receptors of subtype P2Y12. Unlike clopidogrel

Low-dose aspirin and prasugrel, ticagrelor is not a prodrug and does not

Aspirin (75–300 mg daily) is primarily used for secondary require metabolic activation for antiplatelet activity.16

prevention of thromboembolic cardiovascular and

cerebrovascular disease. Patients also self-prescribe aspirin Vorapaxor

based upon professional recommendation or a belief it will Vorapaxar is a novel antiplatelet agent which was granted

offer cardiovascular protection. It irreversibly acetylates by the European Union marketing authorisation in June

cyclooxygenase-1 to inhibit thromboxane-A2 production 2015 for secondary prevention of thrombotic cardiovascular

and reduces platelet aggregation.8 events in patients with a history of myocardial infarction

or peripheral arterial disease.2 It is a tricyclic himbacine-

Clopidogrel derived selective inhibitor of protease-activated receptor-1,

Clopidogrel offers greater thromboembolic protection than a thrombin receptor expressed on platelets. By inhibiting

aspirin in the secondary prevention of myocardial protease-activated receptor-1, vorapaxar prevents thrombin-

infarction, cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular related platelet aggregation.

disease.9 Clopidogrel irreversibly inhibits the adenosine

diphosphate (ADP) receptors on platelet membranes to

reduce platelet aggregation.2 Antiplatelet agent therapy cessation and

thromboembolism risk

Aspirin and clopidogrel dual-therapy

Dual therapy with low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel is used Stopping antiplatelet therapy in the perioperative period is

for patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial particularly hazardous due to increased platelet

infarction and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction aggregation. Thromboembolic events associated with the

2 Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2019; 00: 1–5

MAHMOOD SIDDIQUE MCKECHNIE ANTIPLATELET DRUGS: A REVIEW OF PHARMACOLOGY AND

THE PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS IN ORAL

AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY

interruption of antiplatelet therapy are well recognised and Antiplatelet agent continuation and

although the risk is low the consequences are serious. haemorrhagic risk

Recurrent venous thromboembolism has a mortality of 6%.

Arterial thromboembolism is more serious with a mortality Aspirin continuation

of 20%.17 The nature of surgery will dictate the possible clinical con-

sequences of bleeding. A meta-analysis of 474 studies

Aspirin cessation including 49,590 patients reviewed the thromboembolic

A meta-analysis of 14,981 patients comparing the risks in discontinuing aspirin compared with the haemor-

perioperative continuation with discontinuation of low- rhagic risks with its continuation in the perioperative

dose aspirin revealed that 93 (0.6%) patients who period in a variety of non-cardiac surgical procedures

discontinued aspirin presented with acute vascular events including ophthalmic, dental, visceral, minor general sur-

with 14 (15.1%) of these discontinuing aspirin due to gical and endoscopic procedures. It found that surgeons

dental surgery.18 Furthermore, a review and meta-analysis who were blinded to patient aspirin status could not differ-

of 50,279 patients revealed that aspirin discontinuation had entiate between the two groups according to intraoperative

a detrimental effect regardless of its indication.19 It Is bleeding. Although quantitative bleeding was greater in the

therefore not advised to alter aspirin therapy prior to aspirin cohort, there was no change in mortality and the

surgery, particularly when it is prescribed for secondary bleeding complications could be managed using identical

prevention after cerebrovascular accident, acute coronary measures as without the influence of aspirin and without

syndrome, myocardial infarction or coronary compromising the surgery. However, discontinuing low-

revascularisation. dose aspirin resulted in thromboembolic complications,

including death.18 For dentoalveolar surgery, several small

Clopidogrel cessation prospective observational studies investigated possible

Patients with coronary stents are at high risk of bleeding consequences in continuing perioperative aspirin.

thromboembolic complications. This is particularly Compared with those not taking aspirin, there were no sig-

important for the first 6–12 months after insertion of a nificant differences in mean intraoperative blood loss,

drug-eluting stent and 6–12 weeks after insertion of a bleeding duration or intraoperative bleeding complications

bare-metal stent.7 The most important independent risk that could not be controlled with local measures.25

factor for drug-eluting stent thrombosis within the first 18

months of placement is cessation of clopidogrel therapy.20 Clopidogrel or dipyridamole continuation

In one prospective study of 192 patients who underwent There are few published studies on the relative risks of

non-cardiac surgery within two years of commencing dual perioperative bleeding with clopidogrel or dipyridamole

antiplatelet therapy after PCI21, 5 of 91 (5.5%) patients monotherapy. The pharmacological mechanisms underly-

who had their antiplatelet agents withheld experienced ing the antiplatelet action of these agents suggests patients

an adverse cardiac event. No patients who continued taking these medications will be at no greater risk of

antiplatelet therapy experienced a cardiac complication. excessive bleeding compared with those taking aspirin

Clopidogrel should be continued at the correct dose prior alone.22

to minor oral surgical procedures, 22 but can be stopped

seven days before surgery in patients without stents who Dual therapy continuation

are at low risk of cardiac events and recommenced the For invasive oral procedures, there is little evidence avail-

morning after surgery once haemostasis is achieved.23 able on haemorrhagic complications in patients taking

aspirin and clopidogrel. The TRITON-TIMI 38 trial col-

Dual-therapy cessation lected data on 158 patients who were on dual antiplatelet

A Science Advisory Summary issued jointly by the therapy for acute coronary syndrome (prasugrel and

American Dental Association, American Heart Association, aspirin: 78 patients, clopidogrel and aspirin: 80 patients)

American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular who received oral surgery. There were no bleeding compli-

Angiography and Intervention and American College of cations during the oral surgery procedures but there was

Surgeons emphasised the importance of continuing dual one minor bleeding event reported within seven days in

antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery both groups.16

stents.22 Stopping aspirin and clopidogrel dual therapy in The management of antiplatelet agents depends upon

patients with coronary stents is associated with a five- to taking account of both the haemorrhagic and thromboem-

tenfold increased risk of a myocardial infarction and bolic risks. The vast majority of oral and maxillofacial pro-

mortality. The risk is inversely proportional to the time of cedures are of minor or moderate haemorrhage risk. A

revascularisation and surgery.24 summary of recommendations is outlined in Table 1.

Overall, the risk of coronary thrombosis is greater than

that of surgical haemorrhage, so perioperative cessation of

aspirin and clopidogrel dual therapy should be avoided if

Conclusions

possible.23 Patients on dual antiplatelet therapy should be Oral and maxillofacial surgeons will be involved in the

managed in an oral and maxillofacial surgery unit.24 perioperative management of patients taking antiplatelet

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2019; 00: 1–5 3

MAHMOOD SIDDIQUE MCKECHNIE ANTIPLATELET DRUGS: A REVIEW OF PHARMACOLOGY AND

THE PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS IN ORAL

AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY

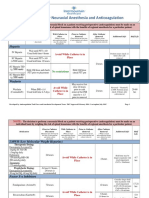

Table 1 Suggested perioperative management of the oral and maxillofacial patient on antiplatelet agents according to cardiac and

bleeding risk levels.

Surgical bleeding risk level Cardiac risk level

Lowa Intermediateb Highc

Low Maintain aspirin Maintain aspirin Elective surgery: Postpone

(dentoalveolar, soft tissue, and/or clopidogrel and/or clopidogrel

salivary gland, minor trauma Urgent surgery:

surgeries; transfusion not required) proceed and maintain

aspirin and/or clopidogrel

Intermediate Maintain aspirin Elective surgery: Elective surgery: Postpone

(oncological resection ± reconstructive, and/or clopidogrel proceed according

orthognathic, vascular, major trauma to risk balance

surgeries; transfusion may be required) Urgent surgery: Urgent surgery:

proceed and proceed and maintain

maintain aspirin aspirin and/or clopidogrel

and/or clopidogrel

High Maintain aspirin Elective surgery: postpone Elective surgery: postpone

(surgery in closed spaces: intracranial Consider stopping Urgent surgery: Urgent surgery: proceed

neurosurgery, posterior eye chamber; clopidogrel 7 days proceed and maintain and maintain aspirin.

craniofacial surgery; transfusion required) before surgery and aspirin. If necessary, If necessary, consider

recommence 24 hours consider stopping stopping clopidogrel

postoperatively after clopidogrel 7 days 7 days before surgery.

haemostasis achieved before surgery and Do not alter dual

recommence 24 hours antiplatelet regime

postoperatively after without seeking advice

haemostasis achieved. from a cardiologist

Do not alter dual

antiplatelet regime

without seeking

advice from a

cardiologist

a

> 3 months after percutaneous coronary intervention, bare-metal stenting or coronary artery bypass grafting; > 6 months after acute

coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction; > 12 months after drug-eluting stenting.

b

6–12 weeks after percutaneous coronary intervention, bare-metal stenting or coronary artery bypass grafting; 6–24 weeks after acute

coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction; > 12 months after high-risk drug-eluting stenting.

c

< 6 weeks after percutaneous coronary intervention, bare-metal stenting, coronary artery bypass grafting, acute coronary syndrome or

myocardial infarction(< 3 months if complications); < 12 months after drug-eluting stenting (may be longer in high-risk drug-eluting

stenting). These delays can be modified according to the amount of myocardium at risk, the instability of the coronary situation or

the risk of spontaneous haemorrhage. The same recommendations apply to newer second-generation drug-eluting stents.

agents for primary or secondary prevention of vascular It is considered safe to continue aspirin throughout the

thrombosis. The surgeon must balance risking primary or oral and maxillofacial perioperative period. Aspirin therapy

recurrent arterial thromboembolism if antiplatelet therapy should not be altered or stopped for surgery when it is

is altered against potentially troublesome or catastrophic prescribed for secondary prevention after cerebrovascular

haemorrhage if therapy is continued. Troublesome accident, acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction

haemorrhagic complications do not carry the same weight or coronary revascularisation.

of risk as thromboembolic complications. Overall, patients Clopidogrel or dipyridamole monotherapy should not

are at greater risk of permanent disability or death if be stopped or altered prior to oral surgical procedures.

antiplatelet therapy is altered before a surgical procedure Clopidogrel should be continued at the correct dose prior

than if it is continued. to minor oral surgical procedure,22 but can be stopped

There has been no single report of uncontrollable seven days before surgery in non-stented patients who

haemorrhage in patients receiving oral surgical procedures are at low risk of cardiac events and recommenced the

and taking dual anti-platelet therapy. Therefore, there is no morning after surgery once haemostasis is achieved.23

indication to interrupt antiplatelet medication in such Current guidance for patients who have received

cases. Bleeding can usually be controlled with local coronary stents recommends that all elective operations

measures. are postponed beyond the recommended time patients are

4 Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2019; 00: 1–5

MAHMOOD SIDDIQUE MCKECHNIE ANTIPLATELET DRUGS: A REVIEW OF PHARMACOLOGY AND

THE PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS IN ORAL

AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY

receiving dual antiplatelet therapy. In such cases, only vital 7. Gershlick AH, Richardson G. Drug eluting stents. BMJ. 2006; 333:

1,233–1,234.

surgery should be undertaken without interrupting dual

8. Dogne J-M, de Leval X, Benoit P et al. Recent advances in antiplatelet agents.

anti-platelet therapy. This is particularly important for Curr Med Chem 2002; 9: 577–589.

patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary 9. CAPRIE Steering Committee. A Randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus

intervention with a bare-metal stent fitted within one aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996; 348:

month or a drug-eluting stent fitted within six months, 1,329–1,339.

10. Sanofi. Plavix 75mg tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium 19 September

because of the increased risk of fatal coronary stent 2019. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5935/smpc (cited October

thrombosis. Aspirin should be continued if clopidogrel 2019).

therapy is stopped.23 Patients on dual antiplatelet therapy 11. Alam M, Goldberg LH. Serious adverse vascular events associated with

should be managed in an oral and maxillofacial surgery perioperative interruption of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy.

Dermatol Surg 2002; 28: 992–998.

unit.22 A 2018 systematic review highlighted the

12. Persantin Retard 200mg capsules. Drugs.com 2019. https://www.drugs.com/uk/

importance of weighing individual risks for coronary stent persantin-retard-200mg-capsules-leaflet.html (cited October 2019).

thrombosis with those of fatal surgical haemorrhage to 13. Lenz TL, Hilleman DE. Aggrenox: a fixed-dose combination of aspirin and

inform clinical decisions. The review also emphasised the dipyridamole. Ann Phamacother 2000; 34: 1,283–1,290.

need to adopt a collaborative multidisciplinary approach 14. Asasantin Retard capsules. Drugs.com 2019. https://www.drugs.com/uk/

asasantin-retard-capsules-leaflet.html (cited October 2019).

through liaison with an interventional cardiologist, 15. Daiichi Sankyo UK Limited. Efient 10 mg film-coated tablets. Electronic

haematologist, anaesthetist and surgeon to enable specific Medicines Compendium November 2018. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/

tailored dual antiplatelet therapy management.26 product/6466/smpc (cited October 2019).

Coronary stent thrombosis is a platelet-induced 16. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators.

Greater clinical benefit of more intensive oral antiplatelet therapy with

phenomenon so heparin has no useful role as bridging

prasugrel in patients with diabetes mellitus in the trial to assess

therapy due to its lack of antiplatelet therapy. Short-acting improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibition

platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (for example with prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38. Circulation 2008;

eptifibatide or tirofiban) are used as a substitute for 118: 1,626–1,636.

clopidogrel while aspirin is being maintained but this has 17. Anderson CS, Jamrozik KD, Broadhurst RJ, Stewart-Wynne EG. Predicting

survival for 1 year among different subtypes of stroke: results from the Perth

not been proven by any randomised controlled trials. Community Stroke Study. Stroke 1994; 25: 1,935–1,944.

Most of the current evidence to guide decision making is 18. Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, Rücker G. Low dose aspirin for

based upon non-randomised observational studies, which secondary cardiovascular prevention: cardiovascular risks after its perioperative

attempts to provide the safest possible management of withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation; review and meta-analysis.

J Intern Med 2005: 257: 399–414.

patients on antiplatelet therapy. Large randomised clinical

19. Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P et al. A systematic review and

trials are lacking. meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin

among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J

2006; 27: 2,667–2,674.

References 20. Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome

1. Korte W, Cattaneo M, Chassot PG et al. Peri-operative management of of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA

antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: joint position 2005; 293: 2,126–2,130.

paper by members of the working group on Perioperative Haemostasis of the 21. Schouten O, van Domburg RT, Bax JJ et al. Noncardiac surgery after coronary

Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Research (GTH), the working group stenting: early surgery and interruption of antiplatelet therapy are associated

on Perioperative Coagulation of the Austrian Society for Anesthesiology, with an increase in major adverse cardiac events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;

Resuscitation and Intensive Care (ÖGARI) and the Working Group Thrombosis 49: 122–124.

of the European Society for Cardiology (ESC). Thromb Haemost 2011; 105: 22. Little JW, Miller CS, Henry RG, McIntosh BA. Antithrombotic agents:

743–749. implications in dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod

2. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Management of Dental 2002; 93: 544–551.

Patients Taking Anticoagulants or Antiplatelet Drugs. Dental Clinical Guidance. 23. Douketis JD, Berger PB, Dunn AS et al. The perioperative management of

Dundee: SDCEP; 2015. antithrombotic therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based

3. Merritt JC, Bhatt DL. The efficacy and safety of perioperative antiplatelet Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008; 133(6 Suppl):

therapy. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2002; 13: 97–103. 299S–339S.

4. Brennan MT, Wynn RL, Miller CS. Aspirin and bleeding in dentistry: an update 24. Airoldi F, Colombo A, Morici N et al. Incidence and predictors of drug-eluting

and recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; stent thrombosis during and after discontinuation of thienopyridine treatment.

104: 316–323. Circulation 2007; 116: 745–754.

5. Grewe PH, Deneke T, Machraoui A et al. Acute and chronic tissue response to 25. Partridge CG, Campbell JH, Alvarado F. The effect of platelet-altering

coronary stent implantation: pathological findings in human specimens. J Am medications on bleeding from minor oral surgery procedures. J Oral Maxillofac

Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 157–163. Surg 2008; 66: 93–97.

6. Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A et al. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: 26. Childers CP, Maggard-Gibbons M, Ulloa JG et al. Perioperative management

delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48: of antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery following

193–202. coronary stent placement: a systematic review. Syst Rev 2018; 7: 4.

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2019; 00: 1–5 5

You might also like

- Oral Surgery in Patients Under Antithrombotic Therapy. Narrative ReviewDocument7 pagesOral Surgery in Patients Under Antithrombotic Therapy. Narrative ReviewAsmy ChubbiezztNo ratings yet

- Articulo - FarmacologíaDocument13 pagesArticulo - FarmacologíaJhon RVNo ratings yet

- Latelet Function Testing Guided Antiplatelet Therapy: Ekaterina Lenk, Michael SpannaglDocument7 pagesLatelet Function Testing Guided Antiplatelet Therapy: Ekaterina Lenk, Michael SpannaglViona PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Antithrombotic Drugs: Pharmacology and Implications For Dental PracticeDocument9 pagesAntithrombotic Drugs: Pharmacology and Implications For Dental PracticeMariana VLedezmaNo ratings yet

- New Antithrombotic Agents in The Ambulatory SettingDocument8 pagesNew Antithrombotic Agents in The Ambulatory SettingyuyoideNo ratings yet

- Dental Management of Patients Receiving Anticoagulation or Antiplatelet TreatmentDocument0 pagesDental Management of Patients Receiving Anticoagulation or Antiplatelet TreatmentmanikantatssNo ratings yet

- Terapia Antiplaquetaria y ExodontiaDocument6 pagesTerapia Antiplaquetaria y ExodontiaDentalib OdontologíaNo ratings yet

- Antipatelet Drug TherapyDocument6 pagesAntipatelet Drug TherapySayali KhandaleNo ratings yet

- Manejo Perioperatorio de Pacientes Usuarios de Antiagregantes PlaquetariosDocument9 pagesManejo Perioperatorio de Pacientes Usuarios de Antiagregantes PlaquetariosErick ToHuNo ratings yet

- 0718 4026 Rchcir 70 03 0291Document9 pages0718 4026 Rchcir 70 03 0291Erick ToHuNo ratings yet

- Aaid Joi D 13 00158Document8 pagesAaid Joi D 13 00158Meta Anjany FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- 309 Novel Anti-Platelet Agents and AnticoagulantsDocument13 pages309 Novel Anti-Platelet Agents and AnticoagulantsPhani NadellaNo ratings yet

- Adj 12751Document13 pagesAdj 12751Irfan HussainNo ratings yet

- What Are Optimal P2Y12 Inhibitor and Schedule of Administration in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome?Document10 pagesWhat Are Optimal P2Y12 Inhibitor and Schedule of Administration in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome?david1086No ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Therapy: New Antiplatelet Drugs in PerspectiveDocument4 pagesAntiplatelet Therapy: New Antiplatelet Drugs in Perspectivegeo_mmsNo ratings yet

- 2019 Anticoagulant Reversal Strategies in The Emergency Department SettingDocument16 pages2019 Anticoagulant Reversal Strategies in The Emergency Department SettingNani BernstorffNo ratings yet

- Anti Platelet PreopDocument6 pagesAnti Platelet Preopbrigde_xNo ratings yet

- Ehad 123Document12 pagesEhad 123Daiane GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Managing Patients Taking Novel Oral Anticoagulants (NOAs) in Dentistry: A Discussion Paper On ClinicDocument14 pagesManaging Patients Taking Novel Oral Anticoagulants (NOAs) in Dentistry: A Discussion Paper On ClinicEliza DraganNo ratings yet

- Br. J. Anaesth. 2007 Chassot 316 28Document13 pagesBr. J. Anaesth. 2007 Chassot 316 28Rhahima SyafrilNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based College of Chest Physicians: American New Antithrombotic DrugsDocument25 pagesEvidence-Based College of Chest Physicians: American New Antithrombotic DrugsDiego Fernando Escobar GarciaNo ratings yet

- Version of Record:: ManuscriptDocument23 pagesVersion of Record:: Manuscriptmiko balisiNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Review On Antithrombotic Therapy For Peripheral Artery DiseaseDocument8 pagesA Comprehensive Review On Antithrombotic Therapy For Peripheral Artery DiseasesunhaolanNo ratings yet

- Fondaparinux in Acute Coronary Syndromes CA5068 Admin OnlyDocument9 pagesFondaparinux in Acute Coronary Syndromes CA5068 Admin OnlynaeamzNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Agents For Stroke PreventionDocument13 pagesAntiplatelet Agents For Stroke PreventionYanthie Moe MunkNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Anesthesia Anagement OnDocument30 pagesPerioperative Anesthesia Anagement OnryandikaNo ratings yet

- AntiagreganteDocument19 pagesAntiagregantecNo ratings yet

- AHA Journals 2020Document52 pagesAHA Journals 2020carla garcíaNo ratings yet

- Hemostasis in Oral Surgery PDFDocument7 pagesHemostasis in Oral Surgery PDFBabalNo ratings yet

- CPG3 Secondary Stroke PreventionDocument10 pagesCPG3 Secondary Stroke Preventionmochamad rizaNo ratings yet

- Antithrombotic Therapy After Revascularization in Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease: What Is Here, What Is NextDocument12 pagesAntithrombotic Therapy After Revascularization in Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease: What Is Here, What Is NextenviNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Therapy in Flow Diversion-2019Document6 pagesAntiplatelet Therapy in Flow Diversion-2019ariNo ratings yet

- Clopi 2Document11 pagesClopi 2Chicinaș AlexandraNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 382 PDFDocument16 pages2019 Article 382 PDFAhmed NahrawyNo ratings yet

- Proton-Pump Inhibitors in Patients Requiring Antiplatelet Therapy: New FDA LabelingDocument7 pagesProton-Pump Inhibitors in Patients Requiring Antiplatelet Therapy: New FDA LabelingRabeprazole Sodium100% (1)

- AnnMaxillofacSurg11175-8428373 232443Document5 pagesAnnMaxillofacSurg11175-8428373 232443Wilson WijayaNo ratings yet

- 2719-Article Text Orig-23698-1-10-20210712Document2 pages2719-Article Text Orig-23698-1-10-20210712Oeij Henri WijayaNo ratings yet

- AFP 2014 12 Clinical RahmanDocument6 pagesAFP 2014 12 Clinical RahmanmyscribeNo ratings yet

- Update On Anti Platelet TherapyDocument4 pagesUpdate On Anti Platelet TherapyhadilkNo ratings yet

- Cortez-Neuroradiology 2020Document10 pagesCortez-Neuroradiology 2020Pedro VillamorNo ratings yet

- Evidencia Clinica de Antiagregantes Plaquetarios y Ima 2015Document11 pagesEvidencia Clinica de Antiagregantes Plaquetarios y Ima 2015Edgar PazNo ratings yet

- AnticuagulacionDocument11 pagesAnticuagulacionLuis EduardoNo ratings yet

- P P22Y Y12 12 Receptors Receptors Antagonists Antagonists: Prof. Medhat Ashmawy Prof. Medhat AshmawyDocument25 pagesP P22Y Y12 12 Receptors Receptors Antagonists Antagonists: Prof. Medhat Ashmawy Prof. Medhat AshmawyNidal OmranNo ratings yet

- On-Treatment Function Testing of Platelets and Long-Term Outcome of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease Undergoing Transluminal AngioplastyDocument8 pagesOn-Treatment Function Testing of Platelets and Long-Term Outcome of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease Undergoing Transluminal AngioplastyGono GenieNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 6Document10 pagesJurnal 6rifkipspdNo ratings yet

- ClopidogrelDocument12 pagesClopidogrelChicinaș AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Kidney News Article p20 7Document2 pagesKidney News Article p20 7ilgarciaNo ratings yet

- Acute StrokeDocument10 pagesAcute StrokeFriska RizalNo ratings yet

- Combined Therapy With Clopidogrel and Aspirin Significantly Increases The Bleeding Time Through A Synergistic Antiplatelet ActionDocument6 pagesCombined Therapy With Clopidogrel and Aspirin Significantly Increases The Bleeding Time Through A Synergistic Antiplatelet ActionAnjas DwikaNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceuticals 05 00279Document18 pagesPharmaceuticals 05 00279babakirisssNo ratings yet

- GI Bleeding in Patients Receiving Antiplatelets and Anticoagulant TherapyDocument11 pagesGI Bleeding in Patients Receiving Antiplatelets and Anticoagulant TherapyTony LeeNo ratings yet

- Haemorrhage and Risk Factors Associated With RetrobulbarDocument12 pagesHaemorrhage and Risk Factors Associated With RetrobulbarVidola Yasena PutriNo ratings yet

- Amlodipine-10mg TabletDocument7 pagesAmlodipine-10mg TabletMd. Abdur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Guide to using a polypill for cardiovascular risk reductionDocument12 pagesGuide to using a polypill for cardiovascular risk reductionjordiNo ratings yet

- 2022 - Antihypertensive Deprescribing in Older Adults - A Practical GuideDocument10 pages2022 - Antihypertensive Deprescribing in Older Adults - A Practical GuideQui Nguyen MinhNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Rivaroxaban Versus Aspirin For Non-Disabling Cerebrovascular Events (TRACE) : Study Protocol For A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesTreatment of Rivaroxaban Versus Aspirin For Non-Disabling Cerebrovascular Events (TRACE) : Study Protocol For A Randomized Controlled TrialVivi NurviantiNo ratings yet

- DVT TreatmentDocument24 pagesDVT TreatmentphoechoexNo ratings yet

- High-Dose Clopidogrel, Prasugrel or Ticagrelor: Trying To Unravel A Skein Into A Ball. Alessandro Aprile, Raffaella Marzullo, Giuseppe Biondi Zoccai, Maria Grazia ModenaDocument8 pagesHigh-Dose Clopidogrel, Prasugrel or Ticagrelor: Trying To Unravel A Skein Into A Ball. Alessandro Aprile, Raffaella Marzullo, Giuseppe Biondi Zoccai, Maria Grazia ModenaDrugs & Therapy StudiesNo ratings yet

- Articulo DR OrtizDocument4 pagesArticulo DR Ortizcarolina Sotomayor BerthetNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet, Anticoagulant and Thrombolytic Agents: Basic Pharmacology Block Pdnt/Pmed - PMSC/PPHR - 213Document30 pagesAntiplatelet, Anticoagulant and Thrombolytic Agents: Basic Pharmacology Block Pdnt/Pmed - PMSC/PPHR - 213JedoNo ratings yet

- Algorithm For Perioperative Management of Anticoagulation1Document8 pagesAlgorithm For Perioperative Management of Anticoagulation1andi namirah100% (1)

- Comparison Between Two Different Local Hemostatic Methods For Dental Extractions in Patients On Dual Antiplatelet Therapy - A Within-Person, Single-Blind, Randomized StudyDocument11 pagesComparison Between Two Different Local Hemostatic Methods For Dental Extractions in Patients On Dual Antiplatelet Therapy - A Within-Person, Single-Blind, Randomized StudySedalys TrainingNo ratings yet

- POINT TrialDocument27 pagesPOINT TrialRutaNo ratings yet

- Clopidogrel - ClinicalKeyDocument79 pagesClopidogrel - ClinicalKeydayannaNo ratings yet

- Classification of Antiplatelet AgentsDocument5 pagesClassification of Antiplatelet AgentsWita Ferani KartikaNo ratings yet

- Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Vs Alteplase For Patients With Minor NondisablingDocument10 pagesDual Antiplatelet Therapy Vs Alteplase For Patients With Minor Nondisablingbetongo Bultus Ocultus XVNo ratings yet

- Herb Drug InteractionsDocument16 pagesHerb Drug Interactionsakotopollan100% (2)

- Aspirin Formulation EvidenceDocument2 pagesAspirin Formulation EvidencekookyinNo ratings yet

- Materia Medica Summary SheetDocument13 pagesMateria Medica Summary Sheetglenn johnstonNo ratings yet

- ICU - Drug InteractionDocument35 pagesICU - Drug InteractionAhmadNo ratings yet

- Charisma TrialDocument10 pagesCharisma TrialYahya AlmalkiNo ratings yet

- Secondary Stroke PreventionDocument17 pagesSecondary Stroke PreventionNidia BracamonteNo ratings yet

- PRADAXA: Dosing Guide: Starting Patients On PRADAXADocument2 pagesPRADAXA: Dosing Guide: Starting Patients On PRADAXAPapp Szodorai BeátaNo ratings yet

- Cardiology: Nature ReviewsDocument15 pagesCardiology: Nature ReviewsluonganhsiNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Stroke Management by The Nurse PR - 2019 - The Journal For Nurse PractDocument9 pagesIschemic Stroke Management by The Nurse PR - 2019 - The Journal For Nurse PractLina SafitriNo ratings yet

- Miscellaneous For FinalsDocument30 pagesMiscellaneous For Finalsjames.a.blairNo ratings yet

- AccrivaDocument8 pagesAccrivaakr200714No ratings yet

- Bleeding Disorders Ce319Document25 pagesBleeding Disorders Ce319cesimpsonNo ratings yet

- Index in Platelet Aggregation Analysis Fea and Effect Antiplatelet TherapiesDocument9 pagesIndex in Platelet Aggregation Analysis Fea and Effect Antiplatelet Therapiesiq_dianaNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewsDocument7 pagesBook Reviewsrahman10191871No ratings yet

- Naturales CapsiumDocument8 pagesNaturales CapsiummaryNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet drugs mechanisms and clinical usesDocument31 pagesAntiplatelet drugs mechanisms and clinical usesPaul Behring ManurungNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument4 pagesDocument PDFDebasis SahooNo ratings yet

- Overview of hemostasis antiplatelets, anticoagulants & fibrinolytic agentsDocument21 pagesOverview of hemostasis antiplatelets, anticoagulants & fibrinolytic agents黄資元100% (1)

- Clopidogrel and AspirinDocument12 pagesClopidogrel and AspirinNandan GuptaNo ratings yet

- Aspirin and Aspilet Compared PDFDocument18 pagesAspirin and Aspilet Compared PDFEfrianti Viorenta HutapeaNo ratings yet

- Orion - Mona NasrDocument169 pagesOrion - Mona Nasrلوى كمال100% (1)

- MCQs PDFDocument234 pagesMCQs PDFPeter Osundwa Kiteki100% (4)

- Academic Emergency Medicine - 2017 - Zahed - Topical Tranexamic Acid Compared With Anterior Nasal Packing For Treatment ofDocument8 pagesAcademic Emergency Medicine - 2017 - Zahed - Topical Tranexamic Acid Compared With Anterior Nasal Packing For Treatment ofathallaNo ratings yet