Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.250 On Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

Uploaded by

akbarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.250 On Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

Uploaded by

akbarCopyright:

Available Formats

Being a Stepparent: Live-In and Visiting Stepchildren

Author(s): Anne-Marie Ambert

Source: Journal of Marriage and Family , Nov., 1986, Vol. 48, No. 4 (Nov., 1986), pp.

795-804

Published by: National Council on Family Relations

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/352572

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

National Council on Family Relations is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Journal of Marriage and Family

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Being a Stepparent: Live-in and

Visiting Stepchildren

ANNE-MARIE AMBERT

York University, Canada

Quantitative and qualitative data are presented to document certain aspects of

perience of stepparenting in a subsample of 109 stepparents. A focus is placed on

of residence of stepchildren as a variable affecting stepparents' marital life, attac

stepchildren, and stepchildren 's relationships with stepparents' own children. For

ple, the stepparenting experience, particularly for stepmothers, was a more po

with live-in stepchildren than with those who live elsewhere. Stepsiblings' rela

also more positive when they lived together rather than visited. The arrival of a c

to the remarried couple had a different impact on the stepparent-stepchild rel

depending on the gender of the stepparent and the stepchild's locale of residen

Studies of divorce and remarriage have minority of stepmothers live with their stepchil-

largely

neglected what it means to be a stepparent dren (Glick,

and1980, 1984).'

how it affects one's life, especially one's Themarital

focus of inquiry in the present study is on

life. It is only recently that researchers and the structural aspects of stepparenting. There are

research-oriented clinicians have focused on this three basic, although not exhaustive, structural

topic, generally as part of studies of the entire stepparenting situations in terms of where the

reconstituted family system and, occasionally, stepchildren

as are living: (a) stepchildren live with

"how-to" books (Brown, 1982; Burgoyne and stepparent; (b) stepchildren live with the other

Clark, 1984; Jacobson, 1979; Maddox, 1975; parent; (c) stepchildren live on their own. Each of

Messinger, 1976; Robinson, 1980; Visher and these living arrangements carries behavioral and

Visher, 1979). A majority of the published studies attitudinal possibilities (see also Clingempeel,

on stepkin relationships have placed a heavy em-Ievoli, and Brand, 1984).

phasis on the experience of stepchildren, especial- Under current custody arrangements, more

ly with their stepfathers (Bohannan, 1975; Ferri,male stepparents experience a live-in stepchild,

1984; Harper, 1984; McCormick, 1974; Perkins while more female stepparents experience a visit-

and Kahan, 1979; Railings, 1976; Stern, 1978). ing stepchild (Glick, 1980). In a majority of the

Fewer studies have focused on stepmothers existing studies referred to earlier, structural

(Bowerman and Irish, 1962; Duberman, 1973; situations are not adequately explored. For in-

Visher and Visher, 1979), perhaps because only astance, we do not know if stepfathers who have

visiting stepchildren are better accepted and ac-

The research for this study was supported by a leave cept their role better than stepfathers who have

fellowship from the Social Science and Humanities live-in stepchildren. On the female side, there are

Research Council of Canada (1984-85), by a SSHRCC many indications that the role of stepmothers may

Faculty of Arts research grant (1984-85), and by a be more difficult than that of stepfathers (Bower-

Faculty of Arts research grant, York University man and Irish, 1962; Burgoyne and Clark, 1982b;

(1985-86). The author gratefully acknowledges the feed-Fishman and Hamel, 1981; Visher and Visher,

back received during a colloquium at the Child Care and 1979), but we do not know how stepfathers and

Development Unit at the University of Cambridge, May

stepmothers compare under the two structural

1985, as well as the helpful comments of two anony-

mous reviewers. situations of visiting and live-in stepchildren (e.g.,

see Duberman, 1973). Unfortunately, obtaining a

Department of Sociology, York University, North sufficiently large and representative sample of

York, Ontario, Canada M3J 1P3. live-in stepmothers to compare with live-in step-

Journal of Marriage and the Family 48 (November 1986): 795-804 795.

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

796 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY

fathers is very difficult because the former situa- METHODS

tion occurs only rarely.

Sample

Another structural variable is whether the new

marriage has produced a child or children.2 How The data presented here were gathered at Time

does this affect the stepparenting experience? 3 of a threC-wave longitudinal and cross-sectional

Again, this question can be answered fully only study of divorced and remarried persons. In

when considered in relation to the first set of 1978--80 (Time 1), 49 separated or divorced per-

structural variables, that is, where the stepchil- sons who were not remarried were interviewed in

dren live. A third variable concerns whether the depth within a semistructured format. The sample

stepparents also had children from a previous was of the snowball type but excluded friends,

marriage and where those children live. The most was not biased by self-selection, and was not

frequent occurrence is for men to have live-in clinical. (Additional details on the sample may be

stepchildren while their own children live with found in Ambert, 1982.) The 26 men and 23

their mothers. These men not only experience women

a had then been separated an average of

disruption in the structure of their paternal role over two years; only 12 were childless. Because of

but are suddenly vested with a new set of children the design requirements of the Time 1 phase, all

who "belong" to their new wives. They havebut to one of the children in these single-parent

devote some time to their stepchildren (if only families

for had to be of school age and living at

the reason of their being present), while they may home (age range: 3 to 19). In 1981, or at Time 2,

resent not being able to see their own children 48 of the 49 respondents were reinterviewed and

more often (see Duberman, 1973; Messinger,their ex-spouses were also interviewed, thus bring-

1984). They may have to support both their live-in ing the sample to 98 respondents.

stepchildren and their own children, and may suf- In 1984, 96 of these persons were reinterviewed

fer from many conflicts of loyalty (Messinger, while a questionnaire was given to their new

1976). spouses when applicable. When the new spouse

We would expect, however, that live-in step- had been divorced, his or her own ex-spouse was

mothers who do not have the custody of their own sought and interviewed while, once again, a ques-

children will suffer from even more conflicts, tionnaire was given this person's new spouse when

because such women are often stigmatized in our applicable, so as to study networks of divorced

society (Duberman, 1973: 287; Spanier and and formerly divorced persons. Thus, at Time 3,

Thompson, 1984: 78). In addition, when women 252 respondents were reached, including 109 step-

opt to leave their children in the custody of their parents who form the basis of this report.

ex-husbands because they wish to be free from the The average age of the 109 stepparents was 36-

daily duties of their maternal role, they may not 40.5 for men and 36 for women who were remar-

be so likely to remarry custodial fathers.3 The ried, and 34 and 30, respectively for the men and

statistical chance that such a double anomaly will women who were in their first marriage (as

occur in a remarriage (a noncustodial mother spouses of remarried persons). The stepparents

married to a custodial father) is slim, which makes had been married or remarried for slightly over

it even more problematic to study. two years on average. In terms of social class,

The purpose of this report is to examine the there was an overrepresentation of interviewees at

diversity and complexity of the structure of the the upper echelons because the Time 1 sample had

stepparenting experience by combining quantita- included more men and women in the higher-SES

tive and qualitative data. Two key areas in the ex- brackets as a result of purposive oversampling of

perience of stepparenting are examined: step- career women and of custodial fathers, who

parents' reported marital life and their perceived tended to be in a higher-SES category.4

relationship with their stepchildren. These two

Data Collection

sets of dependent variables are studied in conjunc-

tion with stepchildren's locale of residence (live-in The interviews addressed the following demo-

stepchildren; stepchildren living with other graphic questions: whether a married person was

parent; and stepchildren living on their own), as a stepparent; where the stepchildren lived;

well as several other variables, namely, where whether there were children born from the remar-

stepparents' children from a previous marriage riage; whether the stepparent was also a parent

live and whether there are children born to the from a previous marriage, and where these chil-

remarriage. Also examined are stepsiblings' rela- dren lived.

tionships as perceived by stepparents. Because Several questions measuring the perceived

many of these issues concern potential gender dif- quality of the stepparents' marital relationship

ferences, the analysis of the data is carried out were included: marital happiness; satisfaction

along gender lines. with spouse; and perception of spouse's satisfac-

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LIVE-IN AND VISITING STEPCHILDREN 797

tion with the respondent. Two other indicators measures forofthe marital relationship and the

the stepparenting experience consisted, first, feelings

stepparents' in for their stepchildren that

asking respondents if they would be "happier, less

were significantly affected by locale of residence

happy, or the same" if they did not have stepchil- but not for stepfathers.

for stepmothers

dren and, second, if they would get along Many of with

the stepfathers in this sample were

their spouse "better, less well, or not married differently"

to the stepmothers they are compared to

without stepchildren. In a section dealing because,with

as indicated earlier, both spouses of a

potential sources of conflict between the remarriage

spouses,were interviewed. Also, because both

one question dealt with conflicts engendered by a divorce were also interviewed,

ex-spouses from

one's stepchildren (spouses always agree manyabout

stepfathers had formerly been married to

stepchildren = 1; always disagree = 5). some of the stepmothers, and vice versa. Thus,

In addition, the interviews allowed us because stepmothers and stepfathers often

to explore

the stepparents' feeling for their stepchildren; belonged tothepairs, the data are dependent. The

stepparents' perception of how closetests their rela-

of significance have to be viewed with this

tionship with their stepchildren was, limitation and percep-in addition to the limitation imposed by

tions of their stepchildren's feelings toward the nature of the sample.

them.5 When the stepparents also were parents

from a previous marriage, four questions focused RESULTS

on the interrelations of these two sets of children:

how they get along, how often they quarrel, howMarital Relationship

they feel about each other, and whether the step- The results of the analysis for the marital rel

parents' own children would be happier without tionship are detailed in Table 1. Only the one-w

stepsiblings. Qualitative data were elicited ANOVAs and chi-squares that are statistically si

throughout the interviews by asking the respon- nificant are presented. (Two-way ANOVAs' m

dents, "Could you talk about this?" or "Now effect for residence were statistically significa

that you've answered all these questions about when one-way ANOVAs by residence were for

your stepchildren, I'd like to hear about this in women.) Stepchildren's locale of residence was

your own words" or "I see you're happy [un- significantly related to six of the eight indicators

happy] about this. Do you care to tell me more?"of marital relationship for stepmothers. The

results for stepfathers were nonsignificant and

Data Analysis

mixed, in that some followed the direction of the

Because of the small cell sizes resulting from theresults for stepmothers while others did not.

several concurrent structural variables, the data Thus, stepmothers who lived with their stepchil-

pertaining to the respondents' stepchildren dren reported a very high level of marital happi-

and/or own children from a previous marriageness and were totally satisfied with their spouses

and the remarriage are analyzed qualitatively after an average of two years of remarriage. These

only. The qualitative data serve to illustrate and stepmothers also believed that their husbands

complement the statistical data and bring addi- were satisfied with them. The stepmothers who

tional understanding of the processes involved in reported getting along best with their husbands

the experience of stepparenting. Indeed, such were these same stepmothers with live-in stepchil-

processes can best be understood and explained dren.

through qualitative material, which presents a In contrast, when stepchildren were relatively

more global perspective as opposed to the less young (from 2 to 12 years old) and lived with the

fluid results of statistical analyses. other parent, stepmothers were less happy

The quantitative analyses in this study include maritally and had more conflicts with their

two-way ANOVAs that were performed for each husbands. They did not feel appreciated by their

indicator of the two variables of marital relation- husbands, nor did they appreciate them as much.

ship and the stepparents' feelings for their step- While stepfathers were not as affected by stepchil-

children in order to test for interaction (gender bydren's locale of residence, for them the ideal situa-

locale of residence). Only one interaction proved tion was when the stepchildren were on their

to be significant. In addition, because of the smallown.6

cell sizes for certain categories of stepparents Nearly one-third of stepparents with live-in

(such as for stepfathers with live-out stepchil-stepchildren but over half of those with stepchil-

dren), we chose to rely on one-way ANOVAs by dren living with the other parent felt that they

residence for each gender separately. Because would get long better with their spouse without

there was no main effect for gender, one-waystepchildren and that their marriage would be

ANOVAs had the advantage of highlighting those happier. The qualitative material presented below

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

798 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY

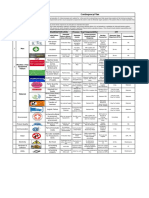

TABLE 1. STEPPARENTS' MARITAL RELATIONSHIP BY STEPCHILDREN'S RESIDENCE AND GENDER OF STEPPARENT

Stepchildren Stepchildren Live Stepchildren Live

Live with Subject with Other Parent on Their Own

Men Women Men Women Men Women

Stepparents' Marital Relationship n = 37 n = 10 n -- 5 n = 42 n = 6 n = 9

1. Marital happiness:

1 = high, 5 = low 1.32 1.20 1.40 2.00 1.33 1.89

2. Satisfaction with spouse:

1 = high, 5 = low 1.32 1.00 1.20 2.26 1.17 2.00

3. Perception of spouse's satisfaction

with self: 1 = high, 5 = low 1.30 1.00 1.80 1.57 1.17 1.22

4. Getting along with spouse:

1 = poor, 4 = well 3.13 3.50 3.00 2.71 3.50 3.33

5. Frequency of arguments with spouse:

1 = many, 4 = none 2.92 3.30 2.80 2.60 3.67 3.11

6. Agreement on spouse's children:

1 = always agree, 5 = never agree 1.81 1.90 1.60 2.29 1.33 1.78

7. Marriage would be happier without

stepchildren: % happier 227o 30% 60% 54% 20% 22%

8. If no stepchildren, would get along

with spouse better: % better 30% 30% 40% 40% 20% 22%

Note: 1. One-way ANOVA for women: F = 2.485, p < .092

2. Two-way ANOVA, interaction: F= 3.07, p < .051

One-way ANOVA for women: F = 4.050, p < .023

3. One-way ANOVA for women: F = 3.453, p < .038

4. One-way ANOVA for women: F = 3.643, p < .032

5. One-way ANOVA for women: F = 3.153,p < .050

6. ns

7. Chi-square for women = 11.2075,

4 df, p < .024

8. ns

expresses the stepparenting dilemma quite well. anomaly also led wives to feel more "appreci-

When the stepchildren lived with the other parent, ated" because they contributed to raising "my

the stepparents tended to feel that their marriage husband's children." They knew that the situa-

would be happier without these stepchildren who tion was unusual in that few divorced men have

came in for disquieting visits and whose other custody of their children. These wives felt closer

parent often ruined the peace. However, men to their husbands and feared the ex-wives' in-

whose stepchildren lived with the other biological fluence and criticism much less than if their hus-

parent felt that they disagreed slightly less with bands' children were with the ex-wives. The new

their spouse about the stepchildren than when wives unavoidably compared themselves to the ex-

they lived with them. wives and felt superior. The husbands' negative

The following is a summary of the qualitative appraisal of the children's mothers reflected well

material that was gathered in interviews regarding on the live-in stepmothers. In spite of the above

these relationships. While it was not generally advantages, and in spite of their high scores in

easy for either a man or a woman to raise, sup- Table 1, stepmothers also reflected a great deal of

port, and care for live-in stepchildren, the live-in ambivalence about having live-in stepchildren.

situation was felt to be a less divisive one than

when the children lived with the other parent and

Relationship with Stepchildren

came for visits. In the former situation, the newAs shown in Table 2, both stepmothers and

couples mentioned that they had more control

stepfathers developed a closer and deeper rela-

tionship with their live-in stepchildren than with

and were less at the mercy of the ex-spouses, while

the stepchildren became part of the households stepchildren living elsewhere. Thus, while step-

rather than occasional and at times disruptive children's locale of residence was not related to

guests. Moreover, when fathers had custody and stepfathers' marital life, it was related to their

remarried, a great deal more planning was feelings toward their stepchildren. Despite the

reportedly done to ensure the stability of the unitshigher positive scores of live-in stepmothers

than if they did not have custody. This stems inshown in Table 2, these women were nonetheless

part from the anomaly of the situation. This ambivalent toward their live-in stepchildren, as

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LIVE-IN AND VISITING STEPCHILDREN 799

TABLE 2. STEPPARENTS' RELATIONSHIP WITH STEPCHILDREN BY STEPCHILDREN'S RESIDENCE AND STEPPAREN 'S'

GENDER

Stepchildren Stepchildren Live Stepchildren Live

Live with Subject with Other Parent on Their Own

Stepparents' Relationship Men Women Men Women Men Women

with Stepchildren n = 37 n = 10 n = 5 n = 43 n = 6 n = 9

1. Closeness of relationship with step-

children: 0 = very close, 8 = no

contact 1.21 1.00 4.60 4.61 4.00 2.11

2. Feelings about stepchildren:

0 = love them, 8 = no contact 0.68 0.80 3.60 2.71 1.60 1.67

3. Perceived stepchildren's feelings

about self: 0 = love me, 8 = no

contact 1.08 0.90 3.80 3.13 2.60 2.67

Note: 1. One-way ANOVA for men: F = 9.327, p < .000

One-way ANOVA for women:

F= 11.212,p < .000

2. One-way ANOVA for men: F = 13.352, p < .000

One-way ANOVA for women: F= 4.173, p < .021

3. One-way ANOVA for men: F = 5.609, p < .007

One-way ANOVA for women: F = 4.868, p < .011

expressed in the following quotation from an It in-

was also noticeable in the interviews that

terview: stepfathers with live-in stepchildren talked about

[One stepmother reports liking her stepson:] them

I less than did similar stepmothers, probably a

would choose him if I were asked to choose a reflection of the fact that stepmothers spent more

time in close proximity to their live-in stepchildren

stepson. He's a nice boy, very nice, mannered,

not difficult. But I find it hard to take care of than did stepfathers with live-in stepchildren.

another woman's son and I have to keep tellingWhen stepfathers talked about their live-in step-

myself that he is my husband's son. I don't think children, it was generally in relation to the con-

it's fair because she never babysits for me and I

flicts of loyalty vis-a-vis their biological children

always do for her. She likes her freedom but it who did not live with them.

seems to me that she's having it at our expense.

After the birth of our first child my husband told

her that . . . her son's weekends would have to

So long as you have stepchildren you might as

be more regular because I needed the rest with well have them with you, otherwise it's too com-

the baby. I think they worked it out but you see it

plicated. It would be more simple if I had my

is a problem to care for a stepchild. There are in-

daughters here all the time. Visiting is a very

equities involved and I am not sure I like being at

complicated arrangement both for parents and

the receiving end.

children. However, I would have preferred not to

This theme of inequity recurred throughout the have acquired stepdaughters. They're cute little

interviews with live-in stepmothers. Two more ex- girls. The only problem is that my own daughters

amples follow. are jealous of them but I think that it is getting

better. I should adopt them but I feel I can't do it

Yes, I feel it's not fair to have to keep someone so long as my own daughters don't live with me.

else's children in general. They're not related to So that part is dicey.

me in any way by blood. If my husband was wid-

owed it would be different because I could

become their mother. However, men and women were equally verbose

I'd rather not have my stepsons. Mind you, I on the topic of stepchildren living with the other

care for them and I am attached to them but I parent. The volume of qualitative material

never set out to have children, and having some-

gathered on this topic in the interviews indicated

one else's children is a burden. I often resent it.

the complexity of the situation. The following is a

At the same time, I wish they didn't have their

quote from a woman reminiscing about the prob-

mother so that way I would benefit at least from

lems created by visiting stepchildren in her pre-

being a mother. But in my situation I have all the

problems a mother has since they live here and vious remarriage:

none of the advantages, maybe less so with the His kids kept coming here because he didn't want

younger one because he was so little when I to visit them at their place, of course, because he

moved in. hated his ex-wife. We had six kids here at times

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

800 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY

parent.the

and his are the rough type: after they'd gone, In this study, however, the men and

whole house was a mess for us to clean and the women with both children and stepchildren in

fridge was empty and I had to pay. They were

their household had unusually well-functioning

just low class persons in a bad sense. remarriages (and, prior to that, they had had

Thus, while live-in stepchildren were preferable

smoothly functioning divorces during which they

to stepchildren living with the other parent, had maintained an amicable coparental relation-

step-

children were nevertheless a mixed blessing for

ship with their ex-spouse). Any conclusions from

these data are therefore tentative. For a man, at

stepparents, especially stepmothers. Stepparent-

ing was a rewarding affective experience whenleast,

it having custody of his own children in-

worked. But it was often considered to be an ex- creased his chances of a close relationship with

live-in stepchildren. When a man's children lived

ploitative condition, at best a tolerated one. Step-

parenting was a more difficult role for womenwith in their mother, but his stepchildren lived with

this sample because most women had stepchildren him, he was drawn to his stepchildren when he

who lived with the "other woman," and we have had no access to his own children or when they

seen that, in this sample, this was the least had sorely disappointed him. But when he had ac-

favorable condition for stepmothers. cess to them, however limited the access was

(either by himself or by the other parent), he

Stepchildren and Own Children from

maintained a certain distance with his live-in step-

Previous Marriage

children as if fearing to be unfair to his own chil-

In this section and the next, relationships be- dren by giving affection to his wife's children.

tween stepchildren and other family members are

summarized on the basis of qualitative material Stepchildren and New Children

derived from the interviews in this study. These What happens to the stepparent's feelings

descriptions may serve as a source of hypotheses toward stepchildren with the arrival of a child or

for larger studies rather than as generalizable children in the remarriage? Although there were

data. 25 remarriages with at least one "new" child, the

Both men and women felt that their own chil- cell sizes for "new" children were limited for the

dren and their stepchildren were more attached purpose

to of this analysis, not only because most of

each other and were getting along better when the children had been born to persons previously

both sets of children were living together. How-

childless, but also because we were subdividing

ever, there were only three such occurrences for

them by the place of residence of stepchildren as

whom all relevant data were gathered, and these well as by the presence of own children from a

happened to be particularly successful marriages. previous marriage. Thus, there were few cases of

In these three cases, with both sets of stepchildren respondents with both live-in stepchildren and

living with the remarried couple, the strength of children from the new marriage, and only one

the spousal relationship may have integrated the man had live-out stepchildren and children from

entire family. his new marriage. (In other words, only one non-

In contrast, where women were custodial custodial mother had children in her remarriage.)

mothers and had stepchildren who lived with the Both the qualitative and quantitative data in-

other parent, the two sets of children were de-dicate that the five men who had live-in stepchil-

scribed as getting along less well and being less at-dren and a child from the new marriage were not

tached to each other than when living together.only the happiest maritally but were also those

"They [daughters] don't get along well with my stepfathers with the warmest feelings toward their

stepdaughters because there is too much jealousy,stepchildren:

and when these girls [visiting stepdaughters] get

The baby has provided me with a secure feeling;

here they want their father all to themselves and he is the symbol of family life. My wife's daugh-

my little girls have difficulty coping with this." ter [live-in] is a very pleasant child who needs a

However, there were no noncustodial women with father and she is a sharp contrast to my [older,

live-in stepchildren and, conversely, there were no visiting] daughter. These two children have

custodial fathers whose stepchildren lived with healed the wounds .... We have children of our

their own fathers. Thus, we were unable to test own, not a child here and a child there, and no

for possible gender differences of stepparents and custody problems.

parents in this area. In contrast, the three women who had live-in step-

Along the same lines of attachment, stepfatherschildren and a child from the new marriage, al-

and stepmothers were more attached to their live-though very happy maritally, were significantly

in stepchildren when their own children lived with more distant from their live-in stepchildren than

them than when their children lived with the other were all other categories of stepmothers with live-

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LIVE-IN AND VISITING STEPCHILDREN 801

in stepchildren. These three women would have

not the stepfathers, who are primarily responsible

wanted to devote more of themselves to the child

for child care and the functioning of the house-

hold.7

born of this marriage and less to the children born

during the husband's previous marriage: We found that, when stepchildren visited, it

I think I am less patient with them [live-in step- was usually the stepmothers, and not the

children] since he's born. He is mine and they're children's fathers, who acquired extra work

not, but they're always here and I just don't seem (housecleaning, shopping for food, cooking, bed-

to be able to be alone with the baby, you know, making), and this work was perceived as a burden

to get to be a mother. I'd like that so much but because the stepmothers would benefit little emo-

these children are in the way. They have a mother tionally from the visits. However, with live-in

and they don't belong to this marriage. stepchildren, although additional work also befell

the women, they at least felt attached to their

stepchildren, and vice versa. The live-in stepchil-

DISCUSSION

dren were likely to do more household chores and

The results clearly indicate that the help their stepmothers more. Such stepmothers

stepparent-

ing experience is a more positive one tended withtolive-in

feel more secure than the ones whose

stepchildren. Both stepmothers and husband stepfathers

had to visit his children and cater to his

tend to be closer to their stepchildren when

ex-wife, the financially or in terms of house-

whether

stepchildren live with them, rather than hold

in help (Visher and Visher, 1979). When the

another

household. However, even with live-in stepchil-

stepchildren lived with them, stepmothers felt

dren, a great deal of ambivalence about they werestep- raising them and were part of a team

parenting was expressed by stepmothers in this

with their husband (Furstenberg and Spanier,

study. The results also indicate that, after

1984). an visiting situation, stepmothers felt

In the

average of two years of remarriage, the leftperceived

out because their husband's coparental role

quality of stepmothers' marital life was was signifi-

carried out more with the ex-wife than with

cantly affected by the place of residence them. ofThestep-

husband's coparental role was often

children: stepmothers with live-in stepchildren threatening to the new wife's sense of security, as

were most positive, while stepmothers whose

she feared a renewed emotional bond between her

young stepchildren lived with their own mothers

husband and his ex-wife. This insecurity stems in

were the least positive in terms of their part frommarital

the fact that our society lacks clear-cut

life. In contrast, stepfathers' perception norms ofseparating

their the ex-spouses' coparental role

marital life was not significantly affected by the bonding (see Ahrons, 1979, 1980;

from emotional

variable under consideration. Nevertheless, McGoldrick from and Carter, 1980).8

20% to 60% of both stepmothers and stepfathers In the routine of daily contacts, stepchildren

indicated that their marriage wouldand bestepparents

happier developed a closer relationship,

and more harmonious without stepchildren. quarrels were more easily overshadowed by other,

These data are consistent with White and Booth's pleasant daily occurrences. With visiting stepchil-

findings (1985) that the presence of stepchildren dren, a quarrel stood out as the event of the week;

negatively affects the stability of a remarriage. ill feelings simmered without opportunities for

The statistical data as well as the qualitativehealing during the hubbub of daily activities and

material presented in this report also lend support

were often exacerbated by the children's mothers'

to the findings of other researchers who have indi-

own comments. Moreover, fathers were more

cated that the role of stepmother is a more dif- likely to side with their own children when they

ficult one than that of stepfather (Burgoyne were and visiting, leaving the stepmothers feeling

Clark, 1982a; Duberman, 1973; Fishman and bruised, while fathers were more likely to form a

Hamel, 1981; Furstenberg and Nord, 1985). Oncoalition with their new wives in households with

the basis of our structural analysis, we can go one

live-in children (and stepchildren).

step further and hypothesize that the greater dif- Similarly, as in Duberman's study (1975), there

ficulty and complexity of the stepmother role may were indications that the parents' own children

stem from the fact that most stepmothers do not and stepchildren got along better when they lived

have live-in stepchildren-which was the most together most of the time than when one set mere-

favorable structural variable in this study from ly visited the house of the other. The rationale for

the stepmothers' perspective (but not from that of

this observation would follow the same line as

stepchildren in Furstenberg and Nord's study,that delineated above for the stepparents.

1985). In contrast, most stepfathers have live-in We have also seen that a combination of one's

stepchildren. A second explanation may well children and stepchildren living in the household

reside in that it is generally the stepmothers, and

was positive for both stepmothers and step-

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

802 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY

fathers, but that the combination of live-in step- FOOTNOTES

children and new children from the current mar-

1. Comparisons regarding relationships and attitu

riage was less favorable for the relationships be- have also been made between families with step-

tween stepmothers and live-in stepchildren. Al- fathers and with natural fathers (Perkins and Kahan,

though the frequencies are so limited that no con- 1979; Santrock, Warshak, Lindberg, and Meadows,

clusions are drawn, these latter data are neverthe-1982; Wilson, Zurcher, McAdams, and Curtis,

less interesting, because women who had children 1975).

from a previous marriage as well as live-in step-

children were the most attached stepmothers.2.The Duberman's work (1973, 1975) was especially

implication is that, since both sets of childrenhelpful for devising the structural orientation of the

present study.

were from a previous marriage, they had a similar

meaning to the women. These children repre- 3. There is no literature documenting this directly;

sented the past and were equal. In comparison,however, in the current study, not one noncustodial

the children or child born within the current mar- mother remarried a custodial father. Moreover, only

riage had a special meaning: they represented the one of these noncustodial mothers had children from

present. In addition, these women did not have a her remarriage and she clearly indicated that these

child from a previous marriage: the "new" chil- children were to compensate for the loss of her first

dren were their first and only children.9 It is also ones: she had not chosen noncustody and her ex-

possible that these women may have made a husband had manipulated the children away from

her psychologically. (This was corroborated during

clearer distinction between their stepparental and

three interviews with the ex-husband since 1980.)

parental roles (Visher and Visher, 1979).

Men may have an easier time accepting live-in4. The respondents were distributed as follows: 52.5%

stepchildren after their wives have given them a of the men belonged to the higher-SES group, while

child, while women who bear, nurse, and care for 41 % of the women did; 40% of the men were placed

their new child may feel that the live-in stepchil- in the middle-SES category versus 51% of the

dren intrude in their intimacy with their own bio- women, while only 8% of the men and 9% of the

logical child. But there were also indications that women fell in the lower-SES group. However,

the new child made stepmothers tolerate visiting remarried respondents tended to cluster in the

higher- and middle-SES categories, with only 8% in

stepchildren better. Here, it might be hypothe-

the lower SES; in contrast, 43% of the 49 unmarried

sized that, with the arrival of the new child, step- or long-term divorced respondents belonged to the

mothers feel that they finally are on a team with lower SES, indicating that, in this sample, higher-

their husband and may be less threatened by the SES divorced persons were more likely to remarry

visiting stepchildren and their mother. Duberman than those of lower SES. This was especially so

(1975) also found that a new child often con- among men. Among women, the middle- and lower-

tributed to the integration of the reconstituted middle-SES women were the most likely to have

remarried.

family. More recently, White, Brinkerhoff, and

Booth (1985) have found that a new child in- Socioeconomic status was determined by using the

1976 revision of the Blishen scale, which is adapted

creases a live-in stepchild's attachment to his or

to the Canadian classification of occupations,

her stepfather, even to the detriment of the non-

related income, education, and prestige (Blishen and

custodial father.

Roberts, 1976). Women's SES was determined strict-

Both the statistical analyses carried out for this ly on the basis of their own occupations when gain-

report and the qualitative material presented sug- fully employed or even doing full-time unpaid

gest the breadth of research on stepparenting that volunteer work.

has yet to be undertaken. Other variables that

should be considered are the time elapsed since 5. These questions were operationalized as follows:

remarriage, the age of the stepparents and step- "How do you feel about your stepchildren? (love

them, like them a lot, like them some, do not like

children at remarriage, the number and gender of

them, resent them)"; "How would you describe

stepchildren, stepparents' socioeconomic status, your relationship with your stepchildren? (very

and their previous marital status. Because of this close, fairly close, not too close, not close at all, no

multiplicity of relevant variables, large samples contact)"; and "Do you know how they feel about

Will be required for statistical analyses. However, you? (love us ... I don't know)." The coding took

qualitative and semiqualitative studies may prove into account those respondents who liked one step-

equally fruitful in studying the processes involved child but disliked the other, for instance. Thus, in

and in discovering those questions that would be Table 2, love them = 0; like them a lot = 1; like

them some = 3; love/like some but not others = 4

meaningful to explore further (LaRossa and .. to dislike them = 7, and no contact = 8.

Wolfe, 1980; Sprey, 1985).

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LIVE-IN AND VISITING STEPCHILDREN 803

6. "On their own" included married stepchildren Clingempeel, or W. Glenn, R. Ievoli, and E. Brand. 1984.

others old enough to live independently,"Structural as well as complexity and the quality of stepfather-

three cases of adolescents residing in group stepchild

homes.relationship." Family Process 23: 547-560.

Duberman, Lucille. 1973. "Step-kin relationships."

7. Data on the division of labor are available from the Journal of Marriage and the Family 35: 283-292.

author in tabular form. These data show that step- Duberman, Lucille. 1975. The Reconstituted Family.

mothers are responsible for most of the householdChicago: Nelson-Hall.

duties, even though some are raising their husbands'Fast, Irene, and Albert C. Cain. 1966. "The stepparent

children, and most are employed. role: Potential for disturbances in family function-

ing." American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 36:

8. On the lack of institutionalization of the stepparen- 485-491.

Ferri, Elsa. 1984. Stepchildren in the National Child

tal role in general, see Cherlin, 1978; Fast and Cain,

1966; Visher and Visher, 1982. Development Study. London: National Children's

Bureau.

Fishman, Barbara, and Bernice Hamel. 1981. "From

9. The sample did not have a case involving live-in own

children, live-in stepchildren, and "new" chil- nuclear to stepfamily ideology: A stressful change."

dren-the romanticized "yours, mine, and ours" Alternative Lifestyles 2: 181-204.

situation-under one roof. Furstenberg, Frank F., Jr., and Christine Winquist

Nord. 1985. "Parenting apart: Patterns of childrear-

ing after marital disruption." Journal of Marriage

and the Family 47: 893-904.

Furstenberg, Frank F., Jr., and Graham B. Spanier.

1984. Recycling the Family: Remarriage after

Divorce. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

REFERENCES Glick, Paul C. 1980. "Remarriage: Some recent changes

and variation." Journal of Family Issues 4: 455-478.

Ahrons, Constance R. 1979. "'The binuclear family: Glick, Paul C. 1984. "Marriage, divorce, and living ar-

Two households, one family." Alternative Lifestyles rangements: Prospective changes." Journal of Fami-

2: 499-515. ly Issues 5: 7-26.

Ahrons, Constance R. 1980. "Redefining the divorced Harper, Patricia. 1984. Children in Stepfamilies: Their

family: A conceptual framework." Social WorkLegal 6: and Family Status. Policy Background Paper

437-441. No. 4, Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne,

Ambert, Anne-Marie. 1982. "Differences in children's

Australia.

behavior toward custodial mothers and custodial Jacobsen, Doris S. 1979. "Stepfamilies: Myths and real-

fathers." Journal of Marriage and the Family 44: Social Work 24: 202-207.

ities."

73-86. LaRossa, Ralph, and Jane H. Wolf. 1985. "On qualita-

Bohannan, Paul. 1975. Stepfathers and the Mentaltive family research." Journal of Marriage and the

Health of Their Children. La Jolla, CA: La Jolla Family 47: 531-541.

Western Behavioral Service Institute. Maddox, Brenda. 1975. The Half Parent. London:

Blishen, Bernard B., and Hugh A. Roberts. 1976. "A Andre Deutsch.

revised socioeconomic index of occupations in McCormick, M. 1974. Stepfathers: What the Literature

Canada." Canadian Review of Sociology and An- Reveals. La Jolla, CA: Western Behavioral Sciences

thropology 13: 71-79. Institute.

Bowerman, Charles E., and Donald P. Irish. 1962. McGoldrick, Monica, and Elizabeth A. Carter. 1980.

"Some relationships of stepchildren to their "Forming a remarried family." In Elizabeth A.

parents." Marriage and Family Living 24: 113-121. Carter and Monica McGoldrick (eds.), The Family

Brown, D. 1982. The Stepfamily: A Growing Challenge Life Cycle: A Framework for Family Therapy. New

for Social Work. Social Work Monographs, Universi- York: Gardner Press.

ty of East Anglia. Messinger, Lilian. 1976. "Remarriage between di-

Burgoyne, Jacqueline, and David Clark. 1982a. "From vorced people with children from previous marriages:

father to stepfather." In L. McGee and M. O'Brien A proposal for preparation for marriage." Journal of

(eds.), The Father Figure. London: Tavistock. Marriage and Family Counseling 2: 193-200.

Burgoyne, Jacqueline, and David Clark. 1982b. "Re- Messinger, Lilian. 1984. Remarriage: A Family Affair.

constituted families." In R. N. Rapoport, M. F. New York: Plenum.

Fogarty, and R. Rapoport (eds.), Families in Britain.

Perkins, Terry F., and James P. Kahan. 1979. "An em-

London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. pirical comparison of natural father and stepfather

Burgoyne, Jacqueline, and David Clark. 1984. Making- family systems." Family Process 18: 175-183.

A-Go-Of-It: A Study of Stepfamilies in Sheffield. Railings, E. M. 1976. "The special role of the step-

London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. father." Family Coordinator 25: 445-449.

Cherlin, Andrew. 1978. "Remarriage as an incompleteRobinson, Margaret. 1980. "Step-families: A reconsti-

institution." American Journal of Sociology 84: tuted family system." Journal of Family Therapy 2:

634-649. 45-69.

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

804 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY

Santrock, John W., Richard Warshak, C. Lindbergh, Visher, Emily B., and John S. Visher. 1982. Stepfami-

and L. Meadows. 1982. "Children's and parents' ob- and Realities. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

lies: Myths

served social behavior in stepfather families." White, Child

Lynn K., and Alan Booth. 1985. "The quality

Development 53: 472-480. and stability of remarriages: The role of stepchil-

Spanier, Graham B., and Linda Thompson. 1984. dren."Part-

American Sociological Review 689-698.

ing: The Aftermath of Separation andWhite, Divorce.Lynn K., David B. Brinkerhoff, and Alan

Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Booth. 1985. "The effect of marital disruption on

Sprey, Jetse. 1985. "Editorial comments." Journal child's attachment

of to parents." Journal of Family

Marriage and the Family 47: 523. Issues 6: 5-22.

Stern, P. N. 1978. "Stepfather families: Integration Wilson, Kenneth L., Louis A. Zurcher, Diana C. Mc-

around child discipline." Issues in Mental Health Adams, and Russell C. Curtis. 1975. "Stepfathers

Nursing 1: 50-56. and stepchildren: An exploratory analysis from two

Visher, Emily B., and John S. Visher. 1979. Stepfami- national surveys." Journal of Marriage and the Fami-

lies: A Guide to Working with Stepparents and Step- ly 37: 526-536.

children. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

I - C I _I

Widows in African Societies

Choices and Constraints

Edited by Betty Potash. Although widows constitute a quarter of the adult female

population in many African societies, they have not been the focus of detailed, cross-

cultural research. This is the first comparative anthropological study of widowhood in

Africa, comprising ten case studies that cover a broad spectrum of societies in different

parts of the continent. It shows clearly that widows are not passive objects of male

transactions; they have interests and options, and make choices affecting their own lives.

The book provides a needed corrective both to the male perspective on kinship and to

women's studies that deal almost exclusively with the adult married women. In contrast

to the traditional emphasis on widow remarriage and the functions such marriages have

for the maintenance of marriage alliances, these papers deal with the women themselves

and the quality of their lives. $35.00

Stanford University Press

STANFORD, CA 94305

a

This content downloaded from

157.193.240.250 on Tue, 17 May 2022 10:47:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Twin Mythconceptions: False Beliefs, Fables, and Facts about TwinsFrom EverandTwin Mythconceptions: False Beliefs, Fables, and Facts about TwinsNo ratings yet

- Number of Siblings, Sibling Spacing, Sex, and Birth Order Their Effects On PerceivedDocument19 pagesNumber of Siblings, Sibling Spacing, Sex, and Birth Order Their Effects On PerceivedJanine Marie SanglapNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.141 On Thu, 06 Jan 2022 13:08:48 UTCDocument10 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.141 On Thu, 06 Jan 2022 13:08:48 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- Wiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentDocument10 pagesWiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentAstridNo ratings yet

- Nonfamily Living and The Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young AdultsDocument15 pagesNonfamily Living and The Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young AdultsNajmul Puda PappadamNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.220 On Tue, 08 Mar 2022 12:17:31 UTCDocument12 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.220 On Tue, 08 Mar 2022 12:17:31 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- Ganong Et Al - A Meta-Analytic Review of Family Structure Stereotypes - 1990Document12 pagesGanong Et Al - A Meta-Analytic Review of Family Structure Stereotypes - 1990Anna MariaNo ratings yet

- KhenDocument67 pagesKhenApril RoxasNo ratings yet

- JournalofFamilyIssues 2009 Mitchell 1651 70Document21 pagesJournalofFamilyIssues 2009 Mitchell 1651 70makmurNo ratings yet

- Grandparenting and Its Relationship To ParentingDocument30 pagesGrandparenting and Its Relationship To ParentingElsa PaulinaNo ratings yet

- Perceived Parental SupportDocument32 pagesPerceived Parental SupportGena MatewosNo ratings yet

- Widow and Widower Remarriage: An Analysis in A Rural 19th Century Costa Rican Population and A Cross-Cultural DiscussionDocument7 pagesWidow and Widower Remarriage: An Analysis in A Rural 19th Century Costa Rican Population and A Cross-Cultural DiscussionMaría Julia BarbozaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Imprisonment On Families and ChildrDocument22 pagesThe Effects of Imprisonment On Families and ChildrwhatamjohnbnyNo ratings yet

- Manual PcrsDocument11 pagesManual PcrsAJNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 163.22.18.73 On Sat, 23 Apr 2022 04:45:01 UTCDocument4 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 163.22.18.73 On Sat, 23 Apr 2022 04:45:01 UTC杜智平No ratings yet

- Family Ties During Imprisonment 2015Document19 pagesFamily Ties During Imprisonment 2015Νουένδραικος ΧρίστιανοιNo ratings yet

- National Council On Family Relations and Wiley Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Family RelationsDocument3 pagesNational Council On Family Relations and Wiley Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Family RelationsNatalia MocNo ratings yet

- Caught in The Middle: Mothers in Stepfamilies: Shannon E. WeaverDocument22 pagesCaught in The Middle: Mothers in Stepfamilies: Shannon E. WeaverSimona UlrichováNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Choices in Relationships An Introduction To Marriage and The Family 11th Edition KnoxDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Choices in Relationships An Introduction To Marriage and The Family 11th Edition Knoxtoo.tasty.if9ou3100% (48)

- Grandparenting and Adolescent Well-Being: Evidence From The UK and IsraelDocument14 pagesGrandparenting and Adolescent Well-Being: Evidence From The UK and IsraelGokma TampubolonNo ratings yet

- Fischer - 1983 - Mothers and Mothers-in-LawDocument7 pagesFischer - 1983 - Mothers and Mothers-in-LawMary SueNo ratings yet

- Decision-Making in Planned Lesbian Parenting - Commented and AnalyzedDocument22 pagesDecision-Making in Planned Lesbian Parenting - Commented and AnalyzedAshley LisaNo ratings yet

- Katie BrookesDocument18 pagesKatie BrookesManole Eduard MihaitaNo ratings yet

- SOBO, E. Bodies, Kin and Flow Family Planning in Rural JamaicaDocument25 pagesSOBO, E. Bodies, Kin and Flow Family Planning in Rural JamaicafernandoNo ratings yet

- 210314Document45 pages210314Siyabonga NdabaNo ratings yet

- Gay Men Who Become Fathers Via Surrogacy: The Transition To ParenthoodDocument31 pagesGay Men Who Become Fathers Via Surrogacy: The Transition To ParenthoodAyen YambaoNo ratings yet

- Why Polyandry FailsDocument25 pagesWhy Polyandry FailsLilla PferschitzNo ratings yet

- Family Processes Rather Than Form Impact Child DevelopmentDocument11 pagesFamily Processes Rather Than Form Impact Child DevelopmentApril Joy Andres MadriagaNo ratings yet

- 2005, The Effects of Imprisonment On Families and Children of PrisonersDocument22 pages2005, The Effects of Imprisonment On Families and Children of PrisonersEduardo RamirezNo ratings yet

- Teti, D. M., & Ablard, K. E. (1989) - Security of Attachment and Infant-Sibling Relationships: A Laboratory Study. Child Development, 60 (6), 1519.Document11 pagesTeti, D. M., & Ablard, K. E. (1989) - Security of Attachment and Infant-Sibling Relationships: A Laboratory Study. Child Development, 60 (6), 1519.GELNo ratings yet

- J of Marriage and Family - 2015 - Amato - Parent Child Relationships in Stepfather Families and Adolescent Adjustment ADocument16 pagesJ of Marriage and Family - 2015 - Amato - Parent Child Relationships in Stepfather Families and Adolescent Adjustment AakbarNo ratings yet

- FR Marriage 2006-01pr Sandwich GenerationDocument3 pagesFR Marriage 2006-01pr Sandwich GenerationTanja WatzNo ratings yet

- Ebook Cultural Anthropology Canadian Canadian 4Th Edition Haviland Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesEbook Cultural Anthropology Canadian Canadian 4Th Edition Haviland Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFengagerscotsmangk9jt100% (7)

- Cultural Anthropology Canadian Canadian 4th Edition Haviland Solutions ManualDocument10 pagesCultural Anthropology Canadian Canadian 4th Edition Haviland Solutions Manualykydxnjk4100% (22)

- Lesbian Gay ParentingDocument20 pagesLesbian Gay ParentingLCLibrary100% (2)

- Caldera Father Attachment QsetDocument22 pagesCaldera Father Attachment QsetLuciana RizzoNo ratings yet

- The Transition To Fatherhood: Identity and Bonding in Early PregnancyDocument20 pagesThe Transition To Fatherhood: Identity and Bonding in Early PregnancyLuciana RizzoNo ratings yet

- 3 McGoldrick, M. & Carter, B. (2003) - Normal Family Process A New YorkDocument25 pages3 McGoldrick, M. & Carter, B. (2003) - Normal Family Process A New YorkOlinka García HernándezNo ratings yet

- M Fine Reinvestigating 2000Document35 pagesM Fine Reinvestigating 2000Simona UlrichováNo ratings yet

- Residential Patterns of Parents and Their Married Children in Contemporary ChinaDocument25 pagesResidential Patterns of Parents and Their Married Children in Contemporary ChinaIrene ZhangNo ratings yet

- Basic Electronics CourseDocument5 pagesBasic Electronics CourseJmoammar De VeraNo ratings yet

- Sex Typing and Consumer BehaviorDocument8 pagesSex Typing and Consumer Behavioram_lunaticNo ratings yet

- Premarital Sex and The Risk of DivorceDocument12 pagesPremarital Sex and The Risk of DivorceOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Effects of Imprisonment on Families and ChildrenDocument21 pagesEffects of Imprisonment on Families and ChildrenJu100% (1)

- DP47Document77 pagesDP47soffleswafflesNo ratings yet

- Gay Fathers Have Strong Bonds With Their Children Despite MisconceptionsDocument10 pagesGay Fathers Have Strong Bonds With Their Children Despite MisconceptionsKevin Arditti VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Extending Non-Monogamies: T&F Proofs: Not For DistributionDocument15 pagesExtending Non-Monogamies: T&F Proofs: Not For DistributionAaron HellrungNo ratings yet

- Step Parenting PDFDocument7 pagesStep Parenting PDFAmalia R. SholichahNo ratings yet

- Hunter SocialfinalDocument22 pagesHunter Socialfinalapi-495099138No ratings yet

- ChildfreeDocument10 pagesChildfreeJessica PutriNo ratings yet

- Lewis-Lamb 2003 - Fathers' Influences On Children's DevelopmentDocument18 pagesLewis-Lamb 2003 - Fathers' Influences On Children's Developmentİnanç EtiNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Parental Care in Fish Explained by Williams' PrincipleDocument11 pagesThe Evolution of Parental Care in Fish Explained by Williams' PrinciplepomajoluNo ratings yet

- Baber & Monaghan - 1988 - IDocument15 pagesBaber & Monaghan - 1988 - ILília Bittencourt SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of GrandparenthoodDocument22 pagesThe Meaning of Grandparenthoodraudah bungaNo ratings yet

- Artigo Hetherington Cox Cox 1985Document13 pagesArtigo Hetherington Cox Cox 1985ex01010No ratings yet

- The Concept of The Family Demographic and GenealogDocument10 pagesThe Concept of The Family Demographic and GenealogJoana RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Brescoll Attitudes Towards ParentsDocument10 pagesBrescoll Attitudes Towards ParentsAlice KilljoyNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument13 pagesResearch Papertobee_polsci100% (5)

- Module 2 Institutions Family, Marriage and Kinship - Part IDocument4 pagesModule 2 Institutions Family, Marriage and Kinship - Part IMIR SARTAJNo ratings yet

- Men's Psychological Transition To Fatherhood: An Analysis of The Literature, 1989-2008Document13 pagesMen's Psychological Transition To Fatherhood: An Analysis of The Literature, 1989-2008Guy IncognitoNo ratings yet

- Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual ApproachDocument108 pagesFamily Theories and Methods: A Contextual ApproachakbarNo ratings yet

- Development Is Global SouthDocument34 pagesDevelopment Is Global SouthakbarNo ratings yet

- Structural-Functionalism: I Nancy Kingsbury and John ScanzoniDocument12 pagesStructural-Functionalism: I Nancy Kingsbury and John ScanzoniakbarNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.106 On Tue, 22 Nov 2022 13:47:41 UTCDocument10 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.106 On Tue, 22 Nov 2022 13:47:41 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.106 On Tue, 22 Nov 2022 13:47:31 UTCDocument5 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.106 On Tue, 22 Nov 2022 13:47:31 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.5.24 On Mon, 31 Oct 2022 22:56:03 UTCDocument14 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.5.24 On Mon, 31 Oct 2022 22:56:03 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- Family Supportand Child AdjustmentDocument14 pagesFamily Supportand Child AdjustmentakbarNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.5.24 Onf:ffff:ffff On Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCDocument14 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.5.24 Onf:ffff:ffff On Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- The Adjustment of Children in StepfamiliesDocument8 pagesThe Adjustment of Children in StepfamiliesakbarNo ratings yet

- Personal and Social Adjustment of Overachievers and Underachievers-A Comparative StudyDocument17 pagesPersonal and Social Adjustment of Overachievers and Underachievers-A Comparative StudyakbarNo ratings yet

- J of Marriage and Family - 2015 - Amato - Parent Child Relationships in Stepfather Families and Adolescent Adjustment ADocument16 pagesJ of Marriage and Family - 2015 - Amato - Parent Child Relationships in Stepfather Families and Adolescent Adjustment AakbarNo ratings yet

- J of Marriage and Family - 2004 - Amato - Parenting Practices Child Adjustment and Family DiversityDocument14 pagesJ of Marriage and Family - 2004 - Amato - Parenting Practices Child Adjustment and Family DiversityakbarNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.162 On Wed, 26 Oct 2022 15:20:51 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.193.240.162 On Wed, 26 Oct 2022 15:20:51 UTCakbarNo ratings yet

- Done ..... RelevantDocument5 pagesDone ..... RelevantakbarNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis - Dalong Zhao-ZnO TFT Thin Film Passivation - Noise Analysis, Hooge ParameterDocument169 pagesPHD Thesis - Dalong Zhao-ZnO TFT Thin Film Passivation - Noise Analysis, Hooge Parameterjiaxin zhangNo ratings yet

- Digital Banking in Vietnam: A Guide To MarketDocument20 pagesDigital Banking in Vietnam: A Guide To MarketTrang PhamNo ratings yet

- Development of Science in Africa - CoverageDocument2 pagesDevelopment of Science in Africa - CoverageJose JeramieNo ratings yet

- Quick Start Guide - QualiPoc AndroidDocument24 pagesQuick Start Guide - QualiPoc AndroidDmitekNo ratings yet

- Practice Exercise For Final Assessment 2221Document3 pagesPractice Exercise For Final Assessment 2221Guneet Singh ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Skills and Techniques in Counseling Encouraging Paraphrasing and SummarizingDocument35 pagesSkills and Techniques in Counseling Encouraging Paraphrasing and SummarizingjaycnwNo ratings yet

- Articulo SDocument11 pagesArticulo SGABRIELANo ratings yet

- MCA 312 Design&Analysis of Algorithm QuestionBankDocument7 pagesMCA 312 Design&Analysis of Algorithm QuestionBanknbprNo ratings yet

- Fif-12 Om Eng Eaj23x102Document13 pagesFif-12 Om Eng Eaj23x102Schefer FabianNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of History as a Social ScienceDocument14 pagesNature and Scope of History as a Social SciencejustadorkyyyNo ratings yet

- FS2-EP-12 - LanceDocument9 pagesFS2-EP-12 - LanceLance Julien Mamaclay MercadoNo ratings yet

- A Guide For School LeadersDocument28 pagesA Guide For School LeadersIsam Al HassanNo ratings yet

- Fireclass: FC503 & FC506Document16 pagesFireclass: FC503 & FC506Mersal AliraqiNo ratings yet

- Baikal Izh 18mh ManualDocument24 pagesBaikal Izh 18mh ManualMet AfuckNo ratings yet

- AGWA Guide GlazingDocument96 pagesAGWA Guide GlazingMoren AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Samuel Mendez, "Health Equity Rituals: A Case For The Ritual View of Communication in An Era of Precision Medicine"Document227 pagesSamuel Mendez, "Health Equity Rituals: A Case For The Ritual View of Communication in An Era of Precision Medicine"MIT Comparative Media Studies/WritingNo ratings yet

- Sketch 5351a Lo LCD Key Uno 1107Document14 pagesSketch 5351a Lo LCD Key Uno 1107nobcha aNo ratings yet

- The Tower Undergraduate Research Journal Volume VI, Issue IDocument92 pagesThe Tower Undergraduate Research Journal Volume VI, Issue IThe Tower Undergraduate Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Effect of In-Store Shelf Spacing On PurchaseDocument20 pagesEffect of In-Store Shelf Spacing On Purchasesiddeshsai54458No ratings yet

- RPH Sains DLP Y3 2018Document29 pagesRPH Sains DLP Y3 2018Sukhveer Kaur0% (1)

- Engine Cpta Czca Czea Ea211 EngDocument360 pagesEngine Cpta Czca Czea Ea211 EngleuchiNo ratings yet

- Limit of Outside Usage Outside Egypt ENDocument1 pageLimit of Outside Usage Outside Egypt ENIbrahem EmamNo ratings yet

- Contingency PlanDocument1 pageContingency PlanPramod Bodne100% (3)

- Module 1 Power PlantDocument158 pagesModule 1 Power PlantEzhilarasi NagarjanNo ratings yet

- Ice Problem Sheet 1Document2 pagesIce Problem Sheet 1Muhammad Hamza AsgharNo ratings yet

- An Approach To Predict The Failure of Water Mains Under Climatic VariationsDocument16 pagesAn Approach To Predict The Failure of Water Mains Under Climatic VariationsGeorge, Yonghe YuNo ratings yet

- Oracle Property Manager System OptionsDocument6 pagesOracle Property Manager System OptionsAhmadShuaibiNo ratings yet

- M-2 AIS Installation Manual ContentDocument57 pagesM-2 AIS Installation Manual ContentAdi PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Four Golden RuleDocument6 pagesFour Golden RulerundyudaNo ratings yet

- Jallikattu: Are Caste and Gender the Real Bulls to TameDocument67 pagesJallikattu: Are Caste and Gender the Real Bulls to TameMALLIKA NAGLENo ratings yet