Professional Documents

Culture Documents

mooneAMS 3 66

Uploaded by

dikiprestya391Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

mooneAMS 3 66

Uploaded by

dikiprestya391Copyright:

Available Formats

Original Article - Practice Guidelines

Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia: Surgery and

literature review

Access this article online

Website:

Suresh Menon, Srihari Venkatswamy, Veena Ramu, Khurshida Banu, Sham Ehtaih,

www.amsjournal.com Vinay M. Kashyap

DOI:

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Vydehi Institute of Dental Sciences,

10.4103/2231-0746.110088

Quick Response Code:

Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. (Col) Suresh Menon, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery,

Vydehi Institute of Dental Sciences, # 82 EPIP Area, Whitefield, Bangalore, Karnataka - 560 066, India.

E-mail: psurmenon@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Objective: To highlight the clinical and radiologic features and management of craniofacial fibrous dysplasia with review

of literature. Materials and Methods: A retrospective review of 6 patients who underwent surgical treatment in a tertiary

healthcare centre was done using the parameters of patients’ details, clinical features, radiological findings, management

and postoperative review. Results: Of the six patients, 3 females and 2 males were in the 2nd decade of life and 1 male in the

1st decade of life. The disease was restricted to maxilla in 3 patients, involved the temporal and frontal bones in addition to

maxilla in one, involved the frontal bone in one patient and involved frontal and parietal bones in one patient. The primary

reason for seeking treatment in all the 6 cases was facial deformity. There was absence of pain in all 6 cases. For surgical

treatment in all three cases involving the maxilla, the approach was intraoral while bicoronal approach was used for the other

three cases. Treatment consisted of surgical contouring and reshaping the area. All cases were followed up over a period of

2 years with no signs of recurrence. Conclusion: Treatment of craniofacial fibro-osseous lesions is highly individualized. Most

cases of craniofacial fibrous dysplasia manifest as swellings that cause facial deformity and surgical recontouring after cessation

of growth seems to provide the best results.

Keywords: Craniofacial, fibrous dysplasia, monostotic, polyostotic

INTRODUCTION the involvement of multiple adjacent bones of the craniofacial

skeleton. They are also not truly polyostotic because bones outside

Fibrous dysplasia (FD) is a non-neoplastic developmental the craniofacial complex are spared. These conditions have a

hamartomatous disease of the bone, characterised by a blend of slight female predilection. They are seen in the first 3 decades

fibrous and osseous elements in the region. With an incidence of life and usually stabilize when the patient reaches skeletal

of 1:4000-1:10,000 it seems to be a rare disease.[1] It represents maturity. However, there have also been reports of persistence at

approximately 2.5% of all bone lesions and about 7% of all benign later periods underlining their variable clinical behaviour. Fibrous

bone tumors.[2] Initially described as “osteitis fibrosa generalisata” by dysplasia involves the maxilla almost twice as often as the mandible,

von Recklinghausen in 1891 in a patient with skeletal deformities frequenting the posterior region and is usually unilateral in nature.

due to fibrotic bone changes, the disorder became known as “fibrous

dysplasia” in 1938 when Lichtenstein introduced the term.[3] The Diagnosis

three subtypes of FD are monostotic, polyostotic and craniofacial. The most common presenting symptom in fibrous dysplasia is

The term “craniofacial fibrous dysplasia” (CFD) is used to describe a gradual, painless enlargement of the involved bone or bones

fibrous dysplasia where the lesions are confined to contiguous in the craniofacial region, clinically seen as facial asymmetry.

bones of the craniofacial skeleton. Most cases of craniofacial fibrous In long bones there may be malformed extremity, limb pain, or

dysplasia cannot be truly categorized as monostotic because of pathologic fracture. If constriction of foramina or obliteration

66 Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery | January - June 2013 | Volume 3 | Issue 1

Menon, et al.: Craniofacial dysplasia: Literature review

of bony cavities occurs, orbital dystopia, diplopia, proptosis, 2a]. Though the supraorbital and medial orbital regions were

blindness, epiphora, strabismus, facial paralysis, loss of hearing, also involved due to projection of the frontal bones in 2 of these

tinnitus, nasal obstruction, etc., may also be evident. In addition to patients, there were no visual disturbances. The classic clinical

clinical findings, diagnosis is based on results of the radiographic features in maxillary involvement was a well defined bony hard

examination and histopathological findings. swelling in the maxillary region, obliterating the nasolabial groove

with no sensory impairment of infra orbital nerve. Intraorally

Radiological findings the bony overgrowth extended onto the alveolar crest causing a

The radiological signs of CFD are very distinctive, visualised ledge in the posterior region. In one of these patients, the swelling

as a thin cortex with well defined borders and ground-glass involved the nasomaxillary region with obvious obliteration of the

appearance. Radiographically, the appearance varies with the nasal cavity [Figure 1b and c]. The involvement of frontal bone

stage of development and amount of bony matrix within the in three of the patients manifested as prominence of the region

lesion. The radiographic picture is more radiolucent and well creating a very unaesthetic appearance.

defined in the early stages and becomes mottled and more radio

opaque as the disease progresses. Routine radiographs were taken in 3 patients and CT scan in 5 of

the patients [Figures 1b and c, 3a-c]. Conventional radiographs

showed increased radio opaque appearance of the region. The

MATERIALS AND METHODS

area showed a classic ground glass appearance.

The records of 6 patients of craniofacial fibrous dysplasia were

evaluated in terms of patients’ details like age, sex, clinical features, CT findings

radiological picture, management and postoperative review. Patient 1 had thickening of the frontal and parietal regions with

deposition of bone on the inner aspect, at the expense of the

cranial contents [Figures 1b-c]. The frontal area showed thinning

RESULTS

and perforation with loss of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus.

The mean age of the 6 patients was 15.5 years (range, 8-19 years).

3 females and 2 males were in the 2nd decade of life and 1 male Patient 2 showed increased dimensions of the zygoma and partial

in the 1st decade of life. The male to female ratio was 1:1. The obliteration of the right maxillary sinus. In patient 3, there was

universal clinical feature in all six patients was the presence of dense ossification of the maxilla, its antrum and slight raising

facial deformity. In addition, two of the patients complained of of the orbital floor. Patient 5 and 6 showed gross thickening of

nasal obstruction due to obliteration of the nasal cavities. The the frontal and sphenoid regions with a bilateral frontal bossing

average duration of the condition in the six patients was 8 months. including involvement of roof of the orbit. The bone had a mottled

Three of the patients reported with swelling of the maxillary appearance with partial obliteration of the anterior cranial fossa.

region [Figure 1a]. One of these patients also complained of nasal

obstruction of the involved side due to obliteration of the nasal Lab investigations

cavity by the lesion. Three of the patients had obvious swellings Routine investigations including haematology, serum Calcium

on the frontal region causing aesthetic concerns [Figures 1a and and serum Alakaline Phosphatase (ALP) were performed. All

Figure 1: (a) Monostotic maxillary fibrous dysplasia, (b) CT showing extensive maxillary involvement, (c) PNS Radiograph showing maxillary sinus

obliteration, (d) Intraoral view of the lesion - Amount of bone removed, (e) Postoperative PNS view, (f) Postoperative view

Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery | January - June 2013 | Volume 3 | Issue 1 67

Menon, et al.: Craniofacial dysplasia: Literature review

parameters were within normal limits. The approach to the frontal region in 3 patients was the bicoronal

approach. After exposing the calvarium, bone was removed in small

Management instalments using micro saws, rotary instruments and osteotomes

Incision biopsy was done for 4 patients in whom the maxilla was [Figures 1d, 3d-f]. The contour and aesthetics of the region was

involved. A vestibular approach was used to remove the tissue evaluated from time to time by putting back the scalp flap and

and histopathological picture of the 4 patients showed loosely reviewing the appearance. In one of the patients, the frontal sinus

was devoid of anterior wall due to thinning. The sinus lining

arranged curvilinear trabeculae with fibrous elements leading to

was removed and the anterior wall reconstructed with titanium

a diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia.

mesh [Figure 2b].

In 3 patients where the condition was restricted to maxilla, after

No attempt was made to remove the whole lesion till the

naso-endotracheal intubation, a vestibular approach was used to

intracranial part, considering the large thickness of the bone in

deglove the maxilla on the involved side exposing the anterior this region and the absence of any signs or symptoms. In one of

aspect up to the infraorbital rim. The lesion was removed these patients, since maxillary involvement was also present, an

using rotary instruments and osteotomes. The contouring was additional intraoral approach was used to recontour this region.

checked visually for satisfactory appearance. In one of these The aesthetics was restored in these patients as assessed clinically

patients, the nasal cavity was partially obliterated. The piriform and radiologically.

cavity was reshaped by removal of the osseous extension in

the nasal cavity. The specimens were subjected to histopathological examination.

The reports of the 6 individual cases are given in Table 1.

All 6 patients were periodically reviewed every 3 months

for 2 years [Figures 1f and 2b]. All three patients having only

maxillary involvement had to be subjected to another surgical

procedure to remove the remnant overgrowth of the condition

in the alveolar crestal region after 3 months. Subsequent reviews

did not show any recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Von Recklinghausen first described the condition in 1891 in a

patient with skeletal deformities and coined the term “osteitis

fibrosa generalisata”. It was renamed “fibrous dysplasia” in 1938

Figure 2: (a) Photograph showing frontal and parietal involvement, (b) by Lichtenstein. Perhaps the most accurate term to describe fibrous

Postoperative appearance after recontouring dysplasia is “fibro-osseous dysplasia” or “fibrous osteodysplasia.”

Figure 3: (a) CT showing frontal and parietal involvement, (b) Coronal CT view, (c) Sagittal CT view, (d) Removal of bone using osteotome,

(e) Reconstruction of the frontal sinus wall using mesh, (f) The bone chips that were removed during frontal contouring

68 Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery | January - June 2013 | Volume 3 | Issue 1

Menon, et al.: Craniofacial dysplasia: Literature review

Table 1: Histopathological report of the cases skeleton but are not truly polyostotic either because bones outside

the craniofacial complex are usually not involved. Between 50 to

Sex Age Areas involved Histopathological picture 100% of patients with polyostotic disease will have craniofacial

(in years)

involvement, whereas only 10% with monostotic lesions will

M 17 Frontal and Irregular trabecular bone have involvement of these structures.[10]

Parietal with Chinese letter pattern.

Osteoblasts seen at the

periphery of the trabeculae In the maxillofacial region fibrous dysplasia involves the maxilla

M 8 Maxilla Connective tissue stroma almost twice as often as the mandible and is usually seen

with curvilinear trabeculae of in the posterior region. Most of these lesions are unilateral.

immature bone. Connective Eversole et al.,[11] classified the craniofacial type as polyostotic

tissue showed subperiosteal

because many bones of the craniofacial complex are involved

reactive bone formation

F 15 Maxilla Connective tissue stroma with that are separated from each other only by sutures. The

trabeculae of immature bone polyostotic type may be divided into 3 types: (1) craniofacial

in a moderately cellular fibrous FD, in which only the bones of the craniofacial complex are

connective tissue stroma. affected; (2) Lichtenstein-Jaffe type, in which multiple bones of

Basophilic globular material the skeleton are involved with café au lait pigmentations on the

seen as central masses that

skin and rare endocrinopathies in a few of these patients; and (3)

appears to fuse between

themselves and trabeculae

Albright’s syndrome, characterized by the triad of polyostotic

F 15 Maxilla Connective tissue stroma FD (mostly unilateral), café au lait pigmentations on the skin,

with curvilinear trabeculae of and various endocrinopathies.[12] Another very rare and special

immature bone form is the Mazabraud syndrome, describing an association of

M 19 Frontal, temporal Curvilinear trabeculae of the FD with soft tissue myxomas.

and maxilla immature woven bone showing

Chinese pattern. Surrounding

connective tissue is delicate Diagnosis of polyostotic FD is generally based on clinical

and fibrillar symptoms and radiological images. In contrast, the monostotic

F 19 Frontal Loosely arranged fibro FD requires bone biopsy.

cellular connective tissue

with irregularly shaped thin

Most authors state that fibrous dysplasia in all forms occurs equally

bony trabeculae arranged in

Chinese letter pattern without in male and female patients. However, some authors[13] have

osteoblastic rimming noted the slight female predilection. The condition manifests in

M = Male, F = Female

the first 3 decades of life and it is generally believed that many

of the cases would stabilize when the patients reach skeletal

maturity.[14] The variable clinical behaviour of these lesions can

Reed,[4] has defined the condition as an “arrest of bone maturation however be illustrated by the series of fibrous dysplasia patients

in woven bone with ossification resulting from metaplasia of a in the study by Harris et al.,[15] where one patient presented with

nonspecific fibro-osseous type”. pain at 68 years of age.

Schlumberger,[5] first reported single bone involvement by The main presentation of patients with CFD is a diffuse swelling

the disease process and described it as “monostotic fibrous in the affected region. This affects the calvaria, the skull base,

dysplasia”. Presently, the terms “monostotic” (single bone) and the zygoma, the maxilla and the mandible. The maxilla is more

“polyostotic” (multiple bones) are used to describe the extent of often involved than the mandible. The progression of the lesion

this condition in terms of number of bones involved. Monostotic may cause aesthetic impairment and deformities and clinical

fibrous dysplasia (MFD) constitutes about 70-80% of FD patients symptoms such as visual disturbances, proptosis, orbital dystopia,

and is mostly seen in the second and third decade.[6,7] nasal malfunction, dental problems and sensory disturbances in

the affected regions.[16]

The most commonly involved bones are femur, tibia, ribs and

facial bones. The involvement of facial and cranial bones in FD FD can resemble conditions like cherubism and other giant

occurs in nearly 50% of patients with the polyostotic form and cell lesions radiographically and histologically.[17] In general,

in 10-27% of patients with MFD.[8] fibrous dysplasia occurs more readily in membranous bones and

involvement of ethmoids and sphenoid sinus is uncommon as

The polyostotic form is more frequently seen in female patients, and these ossify in a cartilage.[18]

about 25% of all patients with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (PFD)

exhibit the disease in more than half of the skeleton. Etiology

The etiology of FD is not certain and is probably a genetic

FD can occur in both types of bones, endochondral and predisposition. It is assumed that the mutation is sporadic, postzygotic

membranous. In addition to these two entities, another and located on the GNAS1 gene. This gene is found on chromosome

presentation is “craniofacial fibrous dysplasia” where the lesions 20q13 and is responsible for the formation of the alpha subunit of

are confined to contiguous bones of the craniofacial skeleton.[9] stimulating G-proteins.[19] This mutation activates adenylate cyclise

CFD cannot be truly categorized as monostotic because of the and consequently increases intracellular concentrations of cAMP

involvement of multiple adjacent bones of the craniofacial resulting in abnormal osteoblast differentiation and production of

Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery | January - June 2013 | Volume 3 | Issue 1 69

Menon, et al.: Craniofacial dysplasia: Literature review

dysplastic bone. On the other hand it stimulates release of several Small asymptomatic lesions of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton

cytokines (mainly interleukin-6) which cause normal osteoclasts to that are cosmetically acceptable to the patient are best managed

congregate and increase bone resorption.[20] with observation.

Diagnosis Medical therapy has not occupied a prominent role in the

The usual presentation in fibrous dysplasia is a gradual, painless management of fibrous dysplasia to date. Recognition of

enlargement of the involved bone or bones causing facial pathogenesis of this disease led to treatment with biphosphonates.

asymmetry. They control bone erosion by the inhibition of osteoclastic action.

They have a high affinity for hydroxyapatite of resorbed bone and

Other symptoms in CFD are seen due to constriction of cranial remain tied to it for a long period. The drug is incorporated into the

foramina or obliteration of bony cavities. These include anosmia, cellular cytoplasm, inhibiting acid phosphatase secretion thereby

orbital dystopia, diplopia, proptosis, blindness, epiphora, arresting bone resorption.[22] The theory is that the drug stabilizes

strabismus, facial paralysis, hearing loss, tinnitus, etc. the disease and improves the patient’s pain. Another drug that

has been used is pamidronate given intravenously. Pamidronate

With fibrous dysplasia, the primary goal is to distinguish it from containing a basic nitrogen atom in its alkyl side chain represents

other benign fibro-osseous lesions especially ossifying fibroma. a second generation drug, characterized by increased potency of

Ossifying fibroma, unlike FD grows centrifugally and is clearly inhibition of bone resorption and good tolerance.[23] Pamidronate

demarcated from the surrounding normal bone. 60 mg/day through an intravenous route on 3 successive days

reduces osteoclastic activity. This is repeated every 6 months for

18 months. It has been shown to reduce intensity of bony pain,

Radiology bony resorption, and filling of lytic lesions. Another drug that is

CFD patients can be assessed by plain radiography, magnetic mentioned in literature is calcitonin.[24] Vitamin D and calcium

resonance imaging (MRI) or CT-scans. Radiographically, the supplements have also been recommended since serum calcium

appearance of fibrous dysplasia will vary depending on the stage is low in these patients.

of development and quantity of bony matrix within the lesion.

Thus the lesion is more radiolucent and well-defined initially

Though there are no uniformly accepted protocols for treatment

and gradually changes to a mottled, ill-defined radiopacity in the

of CFD, surgical therapy remains the mainstay of therapy for this

later stages. The radiological picture in fibrous dysplasia is very

disease and is directed at correcting or preventing functional

distinctive showing a thin bony cortex with well defined borders

deficits and achieving normal facial aesthetics.

and ground glass appearance. Three distinct patterns have been

described by Panda et al.,[18] The pagetoid appearance on CT

Conservative surgery involves a remodelling procedure aimed

imaging is characterized by bone expansion and scattered islands

at achieving reasonably acceptable aesthetics. This can however

of bone formation in a low-attenuation field. The sclerotic type

result in recurrence, especially during the growth period[25] and

has a homogeneous appearance with a ground-glass appearance.

can range from 15-20%.[16] A more personalised approach is ideal

The cystic type appears as a well defined low-attenuation lesion

in these conditions and the decision to intervene is based on a

with a sclerotic margin.

careful assessment of the disease on the patient functionally and

aesthetically.

Histopathology

The histopathological features are similar in all three types of FD, The presence of the lesion in the craniofacial region is unique

viewed as benign fibroblastic tissue, arranged in a loose, whorled in that the presence of important structures in the vicinity can

pattern interspersed with spicules of woven bone with typical hamper complete removal of the pathology. Treatment for CFD

osteoblastic rimming embedded in fibrous tissue. Areas of cystic aims at achieving cosmetic or functional goals. The surgical

degeneration with hemosiderin laden macrophages, haemorrhage procedure is usually postponed till puberty hoping that the disease

and osteoclasts may also be seen.[21] will undergo remission. Although conservative surgical resection

is ideal, a more radical approach would be mandatory when

Management the skull base is involved with complications of compression

The aim of the surgical treatment in patients with FD is to prevent around foramina and orbital apex. The importance of a long

pathological fractures, control the pain and to reduce bone term follow up following conservative treatment cannot be over

deformities. emphasized. In general, stabilization usually occurs when bone

maturation is completed. Alvares in a 23 year old follow up has

The surgical treatment of CFD aims at correcting the facial shown stabilisation, 13 years after conservative surgery.[26] Some

deformity in most cases and restoring the obliterated foramina authors recommend monitoring patients their whole life to assess

when they cause problems like visual disturbances, proptosis, the progress of the disease. One reason for this is the potential

orbital dystopia, nasal malfunction, etc. for late growth and dysfunction and a small risk of sarcomatous

change. The risk of malignant transformation has been estimated

Recommended treatment options can be divided into 4 categories: to be 0.4% in fibrous dysplasia and 4% in McCune-Albright

1. Observation syndrome, with the craniofacial region most commonly being

2. Medical therapy the site of occurrence.

3. Surgical remodelling

4. Radical excision and reconstruction Serum alkaline phosphatase levels are an important marker in

70 Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery | January - June 2013 | Volume 3 | Issue 1

Menon, et al.: Craniofacial dysplasia: Literature review

detecting recurrence of FD.[27] ALP has been shown to decline Simultaneous occurrence of facial fibrous dysplasia and ameloblastoma.

in patients treated with palmidronate.[23] The authors postulate J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2009;37:102-5.

that recurrence is rare if the postoperative serum ALP level does 8. Ben Hadj Hamida F, Jlaiel R, Ben Rayana N, Mahjoub H, Mellouli T,

Ghorbel M, et al. Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia: A case report. J Fr

not increase after complete resection. If the patient is older than Ophtalmol 2005;28:e6.

17 years and is in a condition that does not allow complete 9. Daves ML, Yardley JH. Fibrous dysplasia of bone. Am J Med Sci

resection, partial resection is recommended because regrowth is 1957;234:590-606.

not significantly probable. Surgery merely for aesthetic purposes 10. Kim DD, Ghali GE, Wright JM, Edwards SP. Surgical treatment of

is sufficient in patients older than 17 years, regardless of their giant fibrous dysplasia of the mandible with concomitant craniofacial

preoperative serum ALP levels. involvement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;70:102-18.

11. Eversole LR, Sabes WR, Rovin S. Fibrous dysplasia: A nosologic problem

in the diagnosis of fibro osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Pathol

In 1990 Chen and Noordhoff proposed a treatment algorithm 1972;1:189.

for the management of craniomaxillofacial fibrous dysplasia 12. Albright F, Butler AM, Hampton AO, Smith P. Syndrome characterized

incorporating aggressive, radical surgery for the resection of by osteitis fibrosa disemminata, areas of pigmentation and endocrine

diseased tissue.[28] For this algorithm, they proposed that the dysfunction, with precocious puberty in females-report of five cases.

N Engl J Med 1937;216:727-46.

head and face could be divided into 4 zones based on the esthetic

13. Kruse A, Pieles U, Riener MO, Zunker Ch, Bredell MG, Grätz KW.

and functional consequences of the disease at each of these sites Craniomaxillofacial fibrous dysplasia: A 10 year database 1996-2006.

and the unique anatomic considerations for operating in each area. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;47:302-5.

14. Rahman AM, Madge SN, Billing K, Anderson PJ, Leibovitch I, Selva D,

Zone 1 represents the fronto-orbito-malar regions of the et al. Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia: Clinical characteristics and long-term

outcomes. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:2175-81.

face. These are esthetically critical and can be adequately

15. Harris WH, Dudley HR Jr, Barry RJ. The natural history of fibrous

reconstructed with simple bone grafting techniques after dysplasia: An orthopedic, pathological and roentgenographic study.

reconstruction. For this region, they recommended radical J Bone Joint Surg Am 1962;44-A: 207-33.

excision and reconstruction. 16. Valentini V, Cassoni A, Marianetti TM, Terenzi V, Fadda MT, Iannetti G.

Craniomaxillofacial fibrous dysplasia: Conservative treatment or radical

Zone 2 refers to the hair bearing scalp. It is not typically an aesthetic surgery? A retrospective study on 68 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg

2009;123:653-60.

concern, and as such, intervention is optional for the patient. 17. Hyckel P, Berndt A, Schleier P, Clement JH, Beensen V, Peters H,

et al.: Cherubism-New hypotheses on pathogenesis and therapeutic

Zone 3 refers to the central skull base including the sphenoid, consequences. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2005;33:61-8.

pterygoid, petrous temporal bone, and mastoid. Given the 18. Panda NK, Parida PK, Sharma R, Jain A, Bapuraj JR. A clinicoradiologic

difficulty in obtaining surgical access to these areas, the authors analysis of symptomatic craniofacial fibro-osseous lesions. Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg 2007;136:928-33.

recommended observation of lesions in this region.

19. Demirdöver C, Sahin B, Ozkan HS, Durmus¸ EU, Oztan HY. Isolated

fibrous dysplasia of the zygomatic bone. J Craniofac Surg 2010;21:1583-4.

Zone 4 comprises the tooth bearing portions of the skull, the 20. Mandrioli S, Carinci F, Dallera V, Calura G. Fibrous dysplasia. The

maxilla and mandible. The authors recommended conservative clinico-therapeutic picture and new data on its etiology. A review of the

management, given the difficulty in reconstructing defects in literature. Minerva Stomatol 1998;47:37-44.

this region. 21. Abdelkarim A, Green R, Startzell J, Preece J. Craniofacial polyostotic

fibrous dysplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg

Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;106:e49-e55.

CONCLUSION 22. Vasikaran SD. Biphosphonates: An overview with special reference to

alendronate. Ann Clin Biochem 2001;38:608-23.

The fibrous dysplasia affecting the craniofacial region is a 23. Kos M, Luczak K, Godzinski J, Klempous J. Treatment of monostotic

fibrous dysplasia with pamidronate. J Craniomaxillofac Surg

distinctive entity, that can in most cases be treated by conservative

2004;32:10-5.

recontouring. The procedure is preferably indicated after the 24. Yasuoka T, Takagi N, Hatakeyama D, Yokoyama K. Fibrous dysplasia

active growth phase has ceased. A long term follow up of these in the maxilla: Possible mechanism of bone remodeling by calcitonin

patients is mandatory considering the probable flare up of treatment. Oral Oncol 2003;39:301-5.

continuous growth of the lesion. 25. Feingold RS, Argamaso RV, Strauch B. Free fibula flap mandible

reconstruction for oral obstruction secondary to giant fibrous dysplasia.

Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;97:196-201.

REFERENCES 26. Alvares LC, Capelozza AL, Cardoso CL, Lima MC, Fleury RN,

Damante JH. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia: A 23-year follow-up of a

1. Assaf AT, Benecke AW, Riecke B, Zustin J, Fuhrmann AW, Heiland M, patient with spontaneous bone remodelling. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

et al. Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia (CFD) of the maxilla in an 11-year Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;107:229-34.

old boy: A case report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012;40:788-92. 27. Park BY, Cheon YW, Kim YO, Pae NS, Lee WJ. Prognosis for craniofacial

2. Ricalde P, Horswell BB. Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia of the fronto-orbital fibrous dysplasia after incomplete resection: AGE and serum alkaline

region: A case series and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg phosphatise. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010;39:221-6.

2001;59:157-67. 28. Chen YR, Noordhoff MS. Treatment of craniomaxillofacial fibrous

3. Lichtenstein L. Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. Arch Surg 1938;36:874-98. dysplasia: How early and how extensive? Plast Reconstr Surg

4. Reed RJ. Fibrous dyplasia of bone. A review of 25 cases. Arch Pathol 1990;86:835-42.

1963;75:480-95.

5. Schlumberger HG. Fibrous dysplasia of single bones (monostotic fibrous Cite this article as: Menon S, Venkatswamy S, Ramu V, Banu K, Ehtaih S,

dysplasia). Mil Surg 1946;99:504-27. Kashyap VM. Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia: Surgery and literature review.

6. Tabrizi R, Ozkan BT. Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia of orbit. J Craniofac Ann Maxillofac Surg 2013;3:66-71.

Surg 2008;19:1532-7. Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: No.

7. Keskin M, Karabekmez FE, Ozkan BT, Tosun Z, Avunduk MC, Savaci N.

Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery | January - June 2013 | Volume 3 | Issue 1 71

You might also like

- Fibrous Dysplasia in The Maxillo-Mandibular Region - Case ReportDocument4 pagesFibrous Dysplasia in The Maxillo-Mandibular Region - Case ReportDaud Yudhistira100% (1)

- Cabt 12 I 5 P 45Document6 pagesCabt 12 I 5 P 45abeer alrofaeyNo ratings yet

- Radiographic Diagnosis of Fibrous Dysplasia in Maxilla: Corresponding Author: Ahmed Z. Abdelkarim, Ahmedz@hawaii - EduDocument8 pagesRadiographic Diagnosis of Fibrous Dysplasia in Maxilla: Corresponding Author: Ahmed Z. Abdelkarim, Ahmedz@hawaii - Edusolikin ikinNo ratings yet

- Solitary central osteoma of mandible in a geriatric patientDocument4 pagesSolitary central osteoma of mandible in a geriatric patientNurul SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Hed 20192Document6 pagesHed 20192Tiago TavaresNo ratings yet

- Semen ToDocument4 pagesSemen ToyesikaichaaNo ratings yet

- Spindle Cell Tumor in Oral Cavity: A Rare Case Report: Ase EportDocument4 pagesSpindle Cell Tumor in Oral Cavity: A Rare Case Report: Ase EportDeka Dharma PutraNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Non-Ossifying Fibroma Case ReportDocument7 pagesMaxillary Non-Ossifying Fibroma Case ReportfavorendaNo ratings yet

- JOralMaxillofacRadiol1125-7816283 214242Document5 pagesJOralMaxillofacRadiol1125-7816283 214242mutiaaulianyNo ratings yet

- Cabt 12 I 3 P 330Document4 pagesCabt 12 I 3 P 330abeer alrofaeyNo ratings yet

- A Case Report of Paget's Disease of Bone Involving Maxilla and Mandible: A Diagnostic DilemmaDocument8 pagesA Case Report of Paget's Disease of Bone Involving Maxilla and Mandible: A Diagnostic DilemmaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0889540613006197Document3 pagesPi Is 0889540613006197mutiaNo ratings yet

- CBCT Findings of Periapical Cemento-Osseous Dysplasia: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesCBCT Findings of Periapical Cemento-Osseous Dysplasia: A Case ReportRestaWigunaNo ratings yet

- 2017 OmrDocument4 pages2017 Omrcalmua1234No ratings yet

- Odontogenic Keratocyst - A Deceptive EntityDocument4 pagesOdontogenic Keratocyst - A Deceptive EntityIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Rare Paediatric Ossifying Fibroma CaseDocument7 pagesRare Paediatric Ossifying Fibroma CaseRika Sartyca IlhamNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1991790212001626Document6 pagesPi Is 1991790212001626Lina NiatiNo ratings yet

- Unilateral Mandibular Swelling in A Young Female Patient A Case ReportDocument4 pagesUnilateral Mandibular Swelling in A Young Female Patient A Case ReportInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 7 OsteosarcomaDocument4 pages7 OsteosarcomaDodNo ratings yet

- 2016 AlAssiriDocument4 pages2016 AlAssiriazizhamoudNo ratings yet

- Osteoma 1Document3 pagesOsteoma 1Herpika DianaNo ratings yet

- Oncology of ENTDocument4 pagesOncology of ENTAlgivar Dial Prima DaudNo ratings yet

- Periostitis Ossificans: Report of Two CasesDocument7 pagesPeriostitis Ossificans: Report of Two CasesIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Irritational Fibroma A Case ReportDocument2 pagesIrritational Fibroma A Case ReportquikhaaNo ratings yet

- Ijcmr 3499Document4 pagesIjcmr 3499AlfirahmatikaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Publication Case Report - Frontal MucoceleDocument3 pages2021 Publication Case Report - Frontal MucoceleMade RusmanaNo ratings yet

- Gardner Syndrome-The Importance of Early Diagnosis A Case Report and Review of LiteratureDocument5 pagesGardner Syndrome-The Importance of Early Diagnosis A Case Report and Review of LiteratureHarsh ChansoriaNo ratings yet

- Endodontc Surgical Management of Mucosal FenistrationDocument3 pagesEndodontc Surgical Management of Mucosal Fenistrationfun timesNo ratings yet

- Broadie 2Document12 pagesBroadie 2Stefana NanuNo ratings yet

- Min 2018Document7 pagesMin 2018CindyNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Kanistika Jha, Manoj AdhikariDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Kanistika Jha, Manoj AdhikariYeraldin EspañaNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Peripheral Cemento-Ossifying Fibroma: Case Series Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesCase Report: Peripheral Cemento-Ossifying Fibroma: Case Series Literature ReviewMariela Judith UCNo ratings yet

- Duplication of The External Auditory Canal Two CasDocument5 pagesDuplication of The External Auditory Canal Two CasIvana SupitNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Osteoblastoma of The MaxillaDocument6 pagesRecurrent Osteoblastoma of The MaxillamandetoperdiyuwanNo ratings yet

- Jced 10 E1145Document4 pagesJced 10 E1145lily oktarizaNo ratings yet

- Rare Case of Large Peripheral Ossifying FibromaDocument5 pagesRare Case of Large Peripheral Ossifying FibromaSwab IndonesiaNo ratings yet

- JURNALDocument4 pagesJURNALrahastuti drgNo ratings yet

- Dentistry: Monostotic Fibrous Dysplasia: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesDentistry: Monostotic Fibrous Dysplasia: A Case ReportkityamuwesiNo ratings yet

- Three-Dimensional Assessment of The Temporal Bone and Mandible Deformations in Patients With Congenital Aural AtresiaDocument3 pagesThree-Dimensional Assessment of The Temporal Bone and Mandible Deformations in Patients With Congenital Aural AtresiaAdarsh GhoshNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic Myxoma A Rare Case ReportDocument3 pagesOdontogenic Myxoma A Rare Case Reportvictorubong404No ratings yet

- Congenital Agenesis of All The Nasal Cartilages: Casereport Craniofacial/MaxillofacialDocument3 pagesCongenital Agenesis of All The Nasal Cartilages: Casereport Craniofacial/MaxillofacialDiego A. Cuadros TorresNo ratings yet

- 2011 TourenoDocument6 pages2011 TourenoazizhamoudNo ratings yet

- Bibliografie CleidocranianaDocument9 pagesBibliografie CleidocranianaMihaela ApostolNo ratings yet

- Bahan Pagets Disease of MaxillaDocument3 pagesBahan Pagets Disease of MaxillayuniNo ratings yet

- Rapidly Progressive Severe Proptosis Esthesioneuroblastoma Case ReportDocument5 pagesRapidly Progressive Severe Proptosis Esthesioneuroblastoma Case ReportSSR-IIJLS JournalNo ratings yet

- Calcifying Odontogenic Cyst With Atypical FeaturesDocument5 pagesCalcifying Odontogenic Cyst With Atypical FeaturesHerminaElenaNo ratings yet

- SyndromeDocument10 pagesSyndromegosleyjNo ratings yet

- Osteopathia Striata With Cranial SclerosisDocument5 pagesOsteopathia Striata With Cranial SclerosisritvikNo ratings yet

- Dentomaxillofacial Radiology (2005) 34, 240-246 Q 2005 The British InstituteDocument7 pagesDentomaxillofacial Radiology (2005) 34, 240-246 Q 2005 The British Institutechonlada_laiedNo ratings yet

- (Polish Journal of Surgery) Rare Facial CleftsDocument6 pages(Polish Journal of Surgery) Rare Facial CleftspatrickpsilvaNo ratings yet

- ParesthesiaoftheupperlipDocument4 pagesParesthesiaoftheupperlipikeuchi_ogawaNo ratings yet

- Pulpitis JurnalDocument2 pagesPulpitis JurnalIsmail YusufNo ratings yet

- CA LS Bướu Nhiều Hốc - Multilocular Radiolucency in the Body of MandibleDocument4 pagesCA LS Bướu Nhiều Hốc - Multilocular Radiolucency in the Body of MandibleThành Luân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Lateral Periodontal CystDocument8 pagesLateral Periodontal CystTejas KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Surgical-Orthodontic Treatment For Severe Malocclusion in A Patient With Osteopetrosis and Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: Case Report With A 5-Year Follow-UpDocument9 pagesSurgical-Orthodontic Treatment For Severe Malocclusion in A Patient With Osteopetrosis and Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: Case Report With A 5-Year Follow-UpIslam GhorabNo ratings yet

- EmbrioDocument3 pagesEmbrioAmmy ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Osteo Blast OmaDocument5 pagesOsteo Blast OmamandetoperdiyuwanNo ratings yet

- Lobodontia Case Report: Unravelling the Wolf TeethDocument3 pagesLobodontia Case Report: Unravelling the Wolf TeethInas ManurungNo ratings yet

- Giant CellDocument5 pagesGiant CellTamimahNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of TMJDocument6 pagesAnatomy of TMJdikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Pebrian21001@mail Unpad Ac IdDocument7 pagesPebrian21001@mail Unpad Ac Idbahasa inggris1No ratings yet

- A&e Test - ATLSDocument15 pagesA&e Test - ATLSZidan AlanaziNo ratings yet

- Jop 12797 PDFDocument7 pagesJop 12797 PDFNada lathifahNo ratings yet

- Thanks For Ordering Gofood Thanks For Ordering Gofood: Total PaidDocument1 pageThanks For Ordering Gofood Thanks For Ordering Gofood: Total Paiddikiprestya391No ratings yet

- 9870 29215 1 PBDocument4 pages9870 29215 1 PBdikiprestya391No ratings yet

- 2 PDFDocument19 pages2 PDFsolikin ikinNo ratings yet

- GoSend order receipt for small package delivery from Bandung to BandungDocument1 pageGoSend order receipt for small package delivery from Bandung to Bandungdikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Lemvis, Sabtu 09 April 2022: Kemuning V Follow Up Bedah Saraf AsnawatiDocument1 pageLemvis, Sabtu 09 April 2022: Kemuning V Follow Up Bedah Saraf Asnawatidikiprestya391No ratings yet

- ABSTRACT A Challenging Surgical Management With Mandible Reshaping of Fibrous Dysplasia in AdolescentDocument3 pagesABSTRACT A Challenging Surgical Management With Mandible Reshaping of Fibrous Dysplasia in Adolescentdikiprestya391No ratings yet

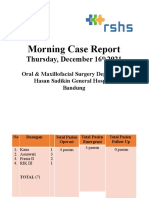

- Morning Case Report: Thursday, December 16 2021Document71 pagesMorning Case Report: Thursday, December 16 2021dikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Fill The Blank Sentences With Negative Form of Simple PresentDocument1 pageFill The Blank Sentences With Negative Form of Simple Presentdikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Dental Expo 2020 Booth Layout and Company ListingDocument12 pagesDental Expo 2020 Booth Layout and Company Listingdikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Pebrian Diki Prestya: Oral Presentation SpeakerDocument1 pagePebrian Diki Prestya: Oral Presentation Speakerdikiprestya391No ratings yet

- BDS 2Document1 pageBDS 2dikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Kumpulan Visi Misi School of DentistryDocument23 pagesKumpulan Visi Misi School of Dentistrydikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Soal Latihan Imperative SentenceDocument3 pagesSoal Latihan Imperative SentenceAnang S100% (2)

- Soal Latihan Imperative SentenceDocument3 pagesSoal Latihan Imperative SentenceAnang S100% (2)

- Nireesh Kumar Paidi - Updated ResumeDocument5 pagesNireesh Kumar Paidi - Updated ResumeNikhil Reddy NamreddyNo ratings yet

- The Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI)Document8 pagesThe Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI)Rakhmatul ArafatNo ratings yet

- Mathematics 2nd Quarter Test With TOSDocument8 pagesMathematics 2nd Quarter Test With TOSRona Mae Aira AvilesNo ratings yet

- Performance Analysis of Cooling TowerDocument7 pagesPerformance Analysis of Cooling TowerIbrahim Al-MutazNo ratings yet

- 3D Bioprinting From The Micrometer To Millimete 2017 Current Opinion in BiomDocument7 pages3D Bioprinting From The Micrometer To Millimete 2017 Current Opinion in Biomrrm77No ratings yet

- 1,16Document138 pages1,16niztgirlNo ratings yet

- 2 Phantom Forces Gui Scripts in OneDocument11 pages2 Phantom Forces Gui Scripts in OneAthallah Rafif JNo ratings yet

- African Healthcare Setting VHF PDFDocument209 pagesAfrican Healthcare Setting VHF PDFWill TellNo ratings yet

- CIB 357th MeetingDocument49 pagesCIB 357th MeetingbarkhaNo ratings yet

- Ames Perception ExperimentsDocument108 pagesAmes Perception ExperimentsMichael RoseNo ratings yet

- Air Pollution Sources & EffectsDocument2 pagesAir Pollution Sources & EffectsJoanne Ash MajdaNo ratings yet

- Cats Meow Edition 3 PDFDocument320 pagesCats Meow Edition 3 PDFbrunokfouriNo ratings yet

- Parts of the Globe: Prime Meridian, Equator and Climate ZonesDocument18 pagesParts of the Globe: Prime Meridian, Equator and Climate Zonesmelgazar tanjayNo ratings yet

- Wa0001.Document1 pageWa0001.Esmael Vasco AndradeNo ratings yet

- 85 KW RequestDocument3 pages85 KW Requestاختر بلوچNo ratings yet

- Footing BiaxialDocument33 pagesFooting BiaxialSanthoshkumar RayavarapuNo ratings yet

- Skin LesionDocument5 pagesSkin LesionDominic SohNo ratings yet

- Calendário Yoruba Primordial PDFDocument18 pagesCalendário Yoruba Primordial PDFNicolas Alejandro Dias MaurellNo ratings yet

- Updated Guiding Overhaul Intervals for MAN B&W EnginesDocument13 pagesUpdated Guiding Overhaul Intervals for MAN B&W EnginesFernando César CarboneNo ratings yet

- Revisiting The Irish Royal Sites: Susan A. JohnstonDocument7 pagesRevisiting The Irish Royal Sites: Susan A. JohnstonJacek RomanowNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Quiz 2 Form A: A. B. C. D. E. F. G. H. I. J. K. L. M. N. O. P. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8Document2 pagesChapter 1 - Quiz 2 Form A: A. B. C. D. E. F. G. H. I. J. K. L. M. N. O. P. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8Olalekan Oyekunle0% (1)

- Week 05 - Mechanical Properties Part 1Document48 pagesWeek 05 - Mechanical Properties Part 1Dharshica MohanNo ratings yet

- Beira Port MozambiqueDocument4 pagesBeira Port Mozambiqueripper_oopsNo ratings yet

- Hydrocarbon ReactionsDocument2 pagesHydrocarbon ReactionsJessa Libo-onNo ratings yet

- Manual: KFD2-UT-E 1Document20 pagesManual: KFD2-UT-E 1Kyrie AbayaNo ratings yet

- July 17, 2015 Strathmore TimesDocument32 pagesJuly 17, 2015 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNo ratings yet

- Pulsar220S PLANOS PDFDocument32 pagesPulsar220S PLANOS PDFJuan Jose MoralesNo ratings yet

- Book Review - Water, Ecosystems and Society A Confluence of Disciplines. by Jayanta BandyopadhyayDocument2 pagesBook Review - Water, Ecosystems and Society A Confluence of Disciplines. by Jayanta BandyopadhyayPDNo ratings yet

- Unit 1.Pptx Autosaved 5bf659481837fDocument39 pagesUnit 1.Pptx Autosaved 5bf659481837fBernadith Manaday BabaloNo ratings yet

- Less Than 60 MilesDocument36 pagesLess Than 60 MilesDavid MckinleyNo ratings yet