Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dementia 2011 Saunders 1471301211421187

Dementia 2011 Saunders 1471301211421187

Uploaded by

Tamta NagervadzeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dementia 2011 Saunders 1471301211421187

Dementia 2011 Saunders 1471301211421187

Uploaded by

Tamta NagervadzeCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/254085813

The discourse of friendship: Mediators of communication among dementia

residents in long-term care

Article in Dementia · May 2012

DOI: 10.1177/1471301211421187

CITATIONS READS

26 292

4 authors:

Pamela Saunders Kate de Medeiros

Georgetown University Miami University

35 PUBLICATIONS 546 CITATIONS 103 PUBLICATIONS 1,139 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Patrick J Doyle Amanda Mosby

Bowling Green State University University of Maryland, Baltimore

17 PUBLICATIONS 202 CITATIONS 6 PUBLICATIONS 80 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

one of several book reviews--not working on now View project

Language and Dementia View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Kate de Medeiros on 05 October 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Article

Dementia

The discourse of friendship: 0(0) 1–15

! The Author(s) 2011

Mediators of communication Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

among dementia residents DOI: 10.1177/1471301211421187

dem.sagepub.com

in long-term care

Pamela A. Saunders

Georgetown University, USA

Kate de Medeiros

Miami University, USA

Patrick Doyle

University of Maryland, USA

Amanda Mosby

University of Maryland, USA

Abstract

One the most difficult challenges experienced by people with dementia and their caregivers is

their communication. The ability to communicate is essential to creating and maintaining social

relationships. Many individuals who suffer from dementia experience increased agitation and

diminished social interaction in the long-term care living setting. This paper demonstrates how,

through language, they construct social relationships. As part of The Friendship Study, which is an

ethnographic observation of persons with dementia living in a long-term care setting, we analyzed

transcripts from video- and audio-taped data and performed a discourse analysis of conversations

to show how persons with dementia who live in a long-term care setting use language to create

friendships. These analyses show that friendships are constructed using concepts such as

conversational objects, discourse deixis, indexicality, and alignment among speakers.

Keywords

alignment, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, discourse, friendship, indexicality, social relationships

Corresponding author:

Pamela A. Saunders, PhD, Departments of Neurology and Psychiatry, Georgetown University, School of Medicine,

Washington, DC 20057, USA

Email: saunderp@georgetown.edu

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

2 Dementia 0(0)

Introduction

Communication problems are among the most difficult faced by people with dementia and

their caregivers (Orange & Colton-Hudson, 1998), contributing to an increase in stress,

mortality, and decreased quality of life for both persons with dementia and their

caregivers (Dunn et al., 1994; Mittelman, Ferris, & Steinberg, 1993; Mobily, Maas,

Buckwalter, & Kelley, 1992; Schulz & O’Brien, 1994; Wright, 1993). A variety of studies

of communication-related stress show that caregivers perceive communication breakdown to

be a major problem in coping with the disease (Clark, 1995; Gurland, Toner, Wilder, Chen,

& Lantigua, 1994; Orange, 1991; Richter, Roberto, & Bottenberg, 1995; Williamson

& Schulz, 1993). For example, Williamson and Schulz (1993) found that communication

problems increase the risk of early institutionalization of the person with dementia. Better

understanding of the processes of communication used by persons with dementia in creating

and maintaining relationships in the long-term care setting might reduce the negative

impacts of communication problems (Orange, 1991). The present paper is part of a larger

ethnographic project, The Friendship Study, examining social interactions of persons with

dementia who live in the long-term care setting.

Background

In the last three decades, most of the research regarding dementia has focused on the

neurobiologic or the neuropsychological processes of the disease (Harris, 2002) and has

made efforts to link these findings with the presentation of symptoms. The aim of

treatment has been almost exclusively to improve cognition and to manage undesirable

behaviors through pharmacologic and behavioral efforts, as well as by the manipulation

of the physical environment. There is a growing body of literature studying psychosocial

dimensions of persons with dementia (Clare, 2002, 2003; Clare, Goater, & Woods, 2006;

Clare & Pearce, 2006; Downs, 1997; Harman & Clare, 2006; Hughes, Louw, & Sabat, 2006;

Keady & Nolan, 1995; Keady, Nolan, & Gilliard, 1995; Kontos, 2006; Leibing & Cohen,

2006; Pearce, Clare, & Pistrang, 2002; Sabat, 2001; Van Dijkhuizen, Clare, & Pearce, 2006;

Cotrell & Schulz, 1993). This current project broadens this body of research by examining

how persons with dementia living in a long-term care setting interact socially and suggests

ways that formal and informal caregivers may learn from these interactions.

Starting with the personhood movement, Kitwood and colleagues (Kitwood, 1993, 1997;

Kitwood & Benson, 1995; Kitwood & Bredin, 1992) have attempted to bring to the forefront

the person-centered approach to dementia research and care. In this approach, the person

with dementia is viewed and treated under the assumption that she or he retains an identity

with which to construct and maintain a self through usual types of social interaction. This

approach views a person with dementia as being the same as any other to the extent that her

or his ‘selfhood’ is publicly manifested in various discursive practices such as telling

autobiographical stories, taking on the responsibility for one’s actions, expressing doubt,

declaring an interest in care, decrying the lack of fairness in a situation (Sabat & Harré,

1992). Our paper examines the language of persons with dementia to show how they

establish social relationships with their conversational partners in the institutional setting.

Kitwood (1993) developed a person-centered approach to evaluating dementia care in

formal settings, called Dementia Care Mapping. He examined the viewpoint of the person

with dementia, using both empathy and observational skills. Working within this

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Saunders et al. 3

framework, Phinney (2002) described the different ways persons with dementia talk about

living with the disease. She pointed out that to understand the symptoms, as people who

actually have the illness experienced and articulated them, provides a richer understanding of

the whole person. In addition, she suggested that intervention strategies are available only by

paying attention to the communicative behaviors of persons with dementia. For example,

persons in the early stages of dementia often fall silent in conversations. It may be because

they are having trouble keeping up with the pace of the conversation. This is a salient issue

for conversations between persons with dementia in the institutional setting. Conversational

partners may limit conversation because they have difficulty keeping pace or understanding

the semantic content. Knowing this, one conversational partner might try to slow down,

making extra effort to repeat or rephrase previous comments and to ensure that the person

with dementia is following along. If the partner has cognitive impairment, there may be

problems accommodating the conversational needs of the other.

Discourse studies of persons with dementia

Social psychologists and sociolinguists have a long tradition of examining the

communicative experiences of persons with dementia. Sabat and Harré (1992) suggested

that it was common to perceive strategies used by persons with dementia as symptoms of

the disease rather than as attempts to maintain selfhood. Communicative behaviors are a

relevant example of this phenomenon. For example, data collected by the present author

(Saunders, 1998a) include a conversation excerpt from the clinical setting between a

physician and a person diagnosed with dementia. When the physician asked the patient,

‘Who is the president of the United States?’, the patient responded, ‘Oh, he was forgettable’.

This statement is open to a variety of interpretations. Clinicians may call this a

circumlocution (i.e. words and phrases substituted for intended word) and view it as a

symptom of the disease, or as a way to save face (a form of semiotic, or meaning-driven,

behavior) in a humorous way, given the speaker’s inability to recall the name of the

president. To interpret this response as also a socially acceptable communication behavior

is to appreciate it as a way to present oneself as a humorous person who has certain opinions

or political views.

Sociolinguistic studies also examine the language and conversational discourse of persons

with dementia in a naturalistic setting. The goal of these studies is to understand social and

psychological interactions through a linguistic analysis. In an important early study,

Hamilton (1994) described a nursing home resident, Elsie, who maintained the ability to

ask and answer questions into advanced stages of dementia. Elsie describes her own memory

loss by saying, ‘I’ve had so many names. . . sometimes they are hard to get’. Ramanathan

(1997) examined the coherence of the speech of people with dementia, noting that

interlocutors frequently ‘take over’ the conversation, reducing opportunities for subjects

to contribute to the conversation. Previous research by the author, Saunders (1998a,

1998b) analyzed the accounts (i.e., explanations) employed by persons with dementia

regarding their memory loss as a means through which to construct personal identity.

For instance, an example of a memory account is shown here:

Clinician: What floor are we on right now?

Patient: I don’t know because I wasn’t paying attention (ha ha).

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

4 Dementia 0(0)

Sociolinguistic studies as referenced above examine language as an analytical unit used by

persons with dementia. These studies shed light on how we understand social relationships of

people with dementia.

Friendships in persons with dementia in long-term care

Research on social relationships within dementia special care units examined dementia

residents’ relationships with staff members (Cohen-Mansfield & Marx, 1992), residents’

friendships related to agitated behaviors (Kutner, Brown, Stavisky, Clark, & Green,

2000), and staff members’ perceptions of residents’ characteristics and successful

social placement (Wood, Cooper, Richardson, & Forbes, 1992). Specifically, Cohen-

Mansfield and Marx (1992) studied relationships between residents with dementia and

‘outsiders’ (e.g. family, friends not living in the nursing home) but not social

relationships among residents. They found increased agitation was associated with

fewer outside social contacts. Kutner et al. (2000) studied friendship and agitated

behaviors among 59 residents of a dementia care unit. Like Cohen-Mansfield and

Marx (1992), Kutner and colleagues found an association between friendship and

lack of agitated behavior. However, these authors did not investigate qualities that

contribute to the formation of friendships, or characterize those friendships, such as

communicative ability, cognition, and physical function (Astell & Ellis, 2006; Chen,

Ryden, Feldt, & Savik, 2000).

Wood et al. (1992) investigated whether residents’ characteristics (specifically

cognition, affect, and mood and/or behavior) influenced staff members’ perceptions of

the residents’ successful placement in a care facility, and found that negative affect and

depressed mood, rather than cognitive function or behavior, were linked with residents’

being labeled ‘unsuccessfully placed’. These authors did not investigate social

interactions among residents but rather whether or not individual residents ‘fit in’ at

the facility.

Even fewer published studies to date have explored friendships specifically among people

with dementia in long-term care. Diaz Moore (1999) conducted participant observation, as

part of his study of social interaction in the dining room of a specialized dementia long-term

care unit, and described three types of social relationships between residents: (1) ‘congenial

friendships’ based on equality of the participants; (2) the ‘clique’ based on similarity or

power of personality; and (3) ‘confidants’ based on asymmetry. Diaz Moore also

characterized staff/resident negotiations as: ‘befriending’, a positive negotiation in which a

staff member is friendly and sociable with a resident; ‘suggesting’, a negotiation technique in

which staff attempts to convince the residents to do something; and ‘invading,’ a strategy in

which staff occupies residents’ space to socialize among themselves. Diaz Moore’s work

provides important insights into how to examine the types of friendships or social

interactions that may exist.

The above studies examine the discourse of persons with dementia using

frameworks that highlight the discourse and language used by persons with

dementia. The current study illustrates examples of social relationships that are

constructed and maintained through language and discourse among residents in the

long-term care setting.

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Saunders et al. 5

Methods

The Friendship Study takes place at Cedar Hill, which is a 20-bed, assisted-living, residential,

care unit for people with moderate to severe dementia. The dementia diagnoses were

determined by the clinical team and confirmed through scores on the Mini-Mental Status

Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). The research team collected data from

residents to characterize their cognition, language, communicative ability, and depression at

Cedar Hill (see the companion article by de Medeiros et al. in this issue). Cedar Hill is a

pseudonym to protect the privacy of the staff and resident participants of this study. The

Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine reviewed

and approved this study. Resident participants were recruited by first contacting their legally

authorized representative (LAR), then obtaining written informed consent from both LAR

and research participant, and then gaining oral assent from residents again at the time of

data collection (Black, Kass, Fogarty, & Rabins, 2007). Staff participants were recruited

through staff meetings where the research team described the study. Staff participants also

signed informed consent documents. The following sections describe in detail both

participant samples.

Participants

Residents. A total of 31 residents (21 women, 10 men) participated in the study over the

course of the 6-month period. Two participants described their race/ethnicity as African

American; the remainder (n ¼ 29) were European American. Years of education ranged from

8 to 20 years (mean 14 years, SD 3.6 years); see the companion article by de Medeiros, et al

in this issue for full details of the subject sample.

Staff. The staff participants (n ¼ 10) were from three Cedar Hill departments: activities

(n ¼ 3), social work (n ¼ 2), and nursing (n ¼ 5). The nursing staff included certified

nursing assistants and medication aids. Staff had to be employed for at least 1 month at

Cedar Hill with a weekly workload of at least 10 hours to be included in the study.

Ethnographic observations

This study conducted ethnographic observations of residents at Cedar Hill for 10 hours per

week for 24 weeks (6 months). The research team members sat quietly in background areas

and took field notes on interactions between residents, the general social environment, and

other overall impressions. The researchers were instructed to be as unobtrusive as possible to

avoid influencing the interaction between residents more than necessary. When possible, to

capture non-verbal data such as facial expressions, physical position, ‘body language,’ and

other cues to communication, the researchers obtained videotaped footage of residents.

Video-taping was limited to common, public areas of the assisted living wing (e.g., dining

room, television lounge, hallways). Residents’ assent to video-taping and/or audio-taping

was obtained at the start of each observational session. Members of the research team

conducted this additional assent process as extra protection for the residents with

dementia to ensure they were willing to be taped each time. Only written notes were used

if residents did not assent to taping or if residents, staff members, or visitors were present for

whom consent had not been obtained. If participating residents did not assent to taping, the

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

6 Dementia 0(0)

researcher took hand-written ethnographic notes. Multi-modal transcription techniques

used to transcribe videotapes include non-verbal communication such as images and

gestures (Baldry & Thibault, 2006; Iedema, 2003). Verbatim transcriptions (Du Bois,

1991) were made of audiotapes.

Most of the interactions reported in this study occurred in the dining room, which served

as the main social space for Cedar Hill residents. Since residents are free to sit in the dining

room at anytime during the day, often they lingered prior to and after meals. They would

walk through this centrally locating dinning space to their rooms and to reach the activity

rooms and other areas of the assisted-living wing. The doors of each wing were open for

residents to move freely between them.

Results

What is the motivation for people with dementia living in long-term care settings to talk to

one another? In the dining room, the present authors observed conversations around

mealtimes. These conversations resembled what one might expect to hear in any dining

room regardless of the diagnosis of the participants. The research team considered this an

important issue of inquiry: who talks to whom and why? Does it depend on similar personal

attributes of the residents, ambulatory function, language ability, or cognitive status?

One finding of the current study was that often the impetus for a conversation involved a

person or an object in the immediate surroundings. These ‘conversational objects’ were

animate items, inanimate items, and abstract concepts in the local surroundings serving to

promote interaction. Apart from the research team’s equipment (e.g., tape recorder), these

objects were part of the everyday décor at Cedar Hill. See Table 1 for a taxonomy of

conversational objects. An animate object includes people and animals. Inanimate objects

include physical or non-living objects that might be found in a home or office environment.

Conversations also focused on topics that are abstract concepts, such as ideas, feelings, or

sounds. Persons with dementia experience anomia (i.e., word-finding problems) and tend to

use function words (e.g., pronouns, determiners) more frequently than content words (e.g.,

nouns and verbs) as their disease progresses. Hence, the ways in which they referenced

conversational objects may be somewhat non-specific. The following examples will

illustrate the use of conversational objects using pronominal reference.

In the following example, Anna, a resident, is sitting with Mary, a staff member, at the

dining table. Anna initiates a conversation by indexing (i.e., pointing to) a tape recorder,

sitting in the center of the dining table. This tape recorder (an inanimate object) serves as a

conversational object. Example 1 begins with Anna’s reaching for the tape recorder and

Mary’s moving it out of Anna’s reach.1

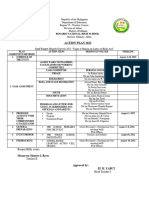

Table 1. Taxonomy of conversational objects.

Animate Inanimate Abstract

People Plants, Trees, Flowers, Activities

(Staff, Residents) Books, Food, Equipment, (Baking, Outings)

Animals (Dogs) Toys, Musical Instruments, Furniture

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Saunders et al. 7

Example 1

1 Anna: (Reaches for tape recorder)

2 Mary: Mm mm- That’s- That can’t be touched. Bet-

3 Anna: But that- it’s mine

4 Mary: No ma’am, it’s not yours. Not yours

5 Anna: I- I put one away like that she tells me

6 Laura: Alright S¼

7 Anna: ¼Like mine¼

8 Laura: ¼I’ll get you it, OK?

9 Anna: Ok, thank you

10 Laura: You’re welcome (Laura brings Anna a glass of water) (pause)

11 Here you go Anna. That one is yours

Anna starts the conversation about a novel object sitting on the dining table. Tape

recorders do not usually appear on the lunch table; thus, its presence is a reasonable

conversation starter. Mary, the staff person, knows the tape recorder belongs to the

research team and tries to keep Anna from touching it. On line 3, Anna claims it belongs

to her by saying, ‘that’s mine’; but Mary disagrees. Anna continues by insisting she had one

in her possession and constructs her story using indefinite terms ‘one’ and ‘that’. In addition,

she supports her story with the report of a third party ‘she tells me’.

Much of the talk in this example is punctuated with discourse deixis, which is the use of

pronouns to refer to people, places, and things (Levinson, 1983). Deictic pronouns are a way

of pointing to things in the environment (Lyons, 1977) using indefinite pronouns (e.g., that,

it). On line 3, Anna refers to the tape recorder with the pronouns, ‘that’ and ‘it’. The use of

non-content words, such as pronouns, is common in the speech of persons with dementia

since anomia is a symptom of the disease. Anna makes herself very clear, as this example

shows by Mary’s response on line 4. The use of pronominal reference allows the person with

dementia to feel that she has made herself clear and initiated a conversation. Such feeling is

an important part of being a social actor in any environment.

Moving from the textual level to the discourse level, Example 1 shows that Anna’s use of

deictic pronouns functions to create cohesion and coherence. Cohesion is what makes a text

semantically meaningful and is achieved through syntactic features, such as deictic,

anaphoric and cataphoric elements2 or a logical tense structure, as well as

presuppositions and implications connected to general world knowledge (Halliday &

Hasan, 1976). Coherence is a broader interpretation by interlocutors regarding the

understandability of the interaction. Anna and Laura together achieve cohesion and

coherence through the sequence of turn taking in which they accept and make sense of

each other’s utterances.

Up to a point, the conversation in Example 1 appears still to be about a tape recorder.

Then, on lines 6 and 8, Laura, another staff member who is serving lunch, says, ‘All right, I’ll

get you it’ and offers Anna a glass of water. Now the textual cohesion is complicated by

another interlocutor. It is unclear whether Laura is trying to distract Anna by offering her a

glass of water or if Laura perceives Anna’s claim ‘that’s mine’ to refer to a glass of water. In

line 9, Anna accepts Laura’s offer and her reinterpretation of the conversational object in

question. This re-framing (Goffman, 1974) is a technique used by caregivers to minimize

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

8 Dementia 0(0)

behavioral disturbances. Was Laura aware of her re-framing? Is this a conversational

diversion on the part of the staff member? The present authors suggest that Laura applied

her knowledge of the resident’s ambiguous discourse and found a solution to the issue of

tape recorder ownership.

In the following excerpt, Liz, a physical therapist at Cedar Hill, has just brought Bob, a

resident, back to the dining room after his therapy session. She assists Bob in navigating

the tables and chairs with his walker and then bids him goodbye. When Bob sits down, he

is joining John, another resident, who is already seated. The conversation with Liz,

the therapist, is included to contextualize the conversation that ensues between Bob

and John.

Example 2

1 Liz: You’re welcome. Thank you: Oops be careful of your walker.

Have a good lunch

2 Bob: OK

3 Liz: I’ll see you I’ll see you on Monday, ok?

4 Bob: OK

5 Liz: We’re going to work on this (points to walker) again

6 Bob: Today (speaks to John sitting across the table from him)

7 John: Shakes his head. I’m not even sure. I don’t know what day it is

8 Bob: No I said¼

9 John: ¼Oh¼

10 Bob: ¼She said, I’ll see you on Monday,

I said ‘today’ (smiles and laughs) (pause)

11 Takes me back about six years ago

12 Haha (Bob starts eating lunch)

13 John: (coughs)

This example illustrates the use of indexicality to create linguistic and social meaning. An

indexical behavior or utterance points to (or indicates) some state of affairs. Indexicality is a

phenomenon far broader than language, one that, independently of interpretation, points to

something, such as smoke as an index of fire (Peirce, 1932). In discourse analysis, indexicality

functions to show how speaker-meaning can be viewed on the sentence level and on the

discourse or interactional level.

In Example 2 on line 6, when Bob said ‘today’, he means he would rather not wait

until Monday to see the physical therapist. Then he addresses his comments to John in

an attempt to start conversation. Liz, the therapist, is the conversational object. The

presence of an attractive young woman serves as a way for one gentleman to initiate

conversation with another. The conversational object is indexed by the word3 ‘today’

and points backward to Liz’s comment on line 3 as well as forward to the present

moment of the lunch table with his dining companion. In pointing backward, Bob

uses an indexical to create meaning and continuity in his discourse. At the same time,

he uses an indexical to point forward. First, he points forward by moving the

conversational center to a new interlocutor, John, and second he points forward by

talking about himself. On line 11, he recalls himself in the past. From this example,

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Saunders et al. 9

we see Bob using language to create coherence in his discourse along a time continuum

from present to past. Bob’s cognitive status of being diagnosed with dementia in the

mild stages as defined by clinical criteria does not interfere with his ability to construct

his own identify as a gentleman who notices ladies and recalls himself as a younger man.

He uses this identity construction in his discourse and to construct his social

relationships.

The next example illustrates an inanimate item as the conversational object and highlights

the use of function words for indexing a social relationship. Here two residents were

sitting down for lunch when a staff member interrupts the conversation to offer a cup of

coffee.

Example 3

1 Bob: How are you doing?

2 Clara: OK.

3 Staff: Would you like a hot cup of coffee?

4 Bob: Yes, I would. [getting ready to sit down]

5 These things don’t move on the carpet at all. [Bob tries to move table]

6 Clara: Not too much. [laughing]

7 Bob: Not at all. [Bob begins to eat and silence returns to the table]

This is an example of a typical interaction between two residents. The conversational

object introduced on line 5, refers to the lunch table. The conversation is short and

punctuated by staff interjections as seen on line 3 when the staff member offers Bob a

cup of coffee. Bob and Clara align themselves with each other using linguistic devices such

as indefinite nouns as in line 5, when Bob says, ‘these things don’t move’. Alignment, as

described by Goffman (1974), is the way we position ourselves in a social interaction. This

may be done by shifting our footing, stance, or the positions that interlocutors take up in

relation to one another and their utterances. Shifts in footing can affect task, tone, social

roles, and interpersonal alignments (Goffman, 1981). Bob is constructing conversational

cohesion through his linguistic usage. Clara’s response ‘Not too much’ serves to support

the construction of coherence in that she agrees with Bob’s assessment that the table does

not move too much on the carpet. Bob continues to align himself with Clara when he

completes the interaction with a repetition of Clara’s statement on line 6, ‘Not too much’.

Indexicality, as a discursive component of the social relationship, is being co-constructed

by Bob and Clara when they align themselves using function words, adverbs, and

prepositions.

Despite the limited verbal exchanges of persons with dementia in long-term care settings,

repeatedly the data revealed that residents aligned themselves to their conversational

partners. Sometimes the work of making friendly conversation can be challenging when

staff members and meal logistics interrupt. Because these conversational interactions can

be so brief, staff members may overlook them and thus may not recognize them as examples

of friendships being created and maintained.

In the next example, two residents are engaged in a conversation that is recognizable as a

friendly interaction based on the topic of food and caring for others.

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

10 Dementia 0(0)

Example 4

1 Lilly: Listen, you better go get something for yourself to eat.

2 Anna: I am not hungry.

3 Lilly: You are very foolish.

4 Anna: My stuff can sit there.

5 If I get hungry

6 I can get it myself.

7 Lilly: You’re not at home now.

8 Anna: I am.

Here Lilly urged Anna to get something to eat and the conversational object is food, an

inanimate item. Lilly expressed, in line 1, her concern for Anna’s state of hunger. Caring for

one another is what friends do for each other. Anna disputed Lilly’s concern, ‘I am not

hungry’ and informed Lilly on line 4 what her plans are if she gets hungry. While Lilly and

Anna seemed to disagree on one level, this author proposes that the indexical behaviors

reveal friendship or, at least, caring between the speakers. Each line is similar in length,

about four or five words. The structure of the sentence follows a similar syntactic pattern

(subject–verb–object). The repetition of pronouns shows alignment. On lines 1, 2, and 5 Lilly

repeats the second person pronoun, ‘you’. Anna matches this pattern by responding

consistently on lines 2, 5, 6, 8 with the first person pronoun, ‘I’. This example illustrates

the concept of indexicality in that the speakers align themselves using language and syntax

that is synchronous and at the same time indexes their social identities: Lilly as the caregiver

and Anna as the self-sufficient.

Discussion

The conversations among persons with dementia reveal many of the elements of

conversation that one would expect in the conversation of non-impaired adults. The

topics chosen to talk about related to their environment: the food, the furniture, and the

people around them. Their discourse serves socially to construct the residents’ identities as

well as their social relationships. While staff members may subscribe to a person-centered

philosophy, may thoughtfully design the physical environment (Brawley, 2006; Briller &

Calkins, 2000), and may plan activities accordingly (Davis, Byers, Nay, & Koch, 2009),

even still, they may not then be aware of the ways in which language in conversational

interaction functions in the social relationships among persons with dementia.

Conversational interactions reveal that residents with dementia in long-term care do

develop and maintain relationships. These relationships focus on the mundane (e.g., the

furniture) as well as personal (e.g., taking care of oneself). The construction of these

relationships is revealed through the discourse: the use of conversational objects and

linguistic elements that show alignment between friends.

Conversational objects are indexed using definite and indefinite pronouns. Residents with

moderate to severe dementia use their linguistic resources to communicate with staff and

other residents, and this use of language is well within their conversational skill set. A

conversational object is an analytical tool to identify the start of a conversation. While

this study highlights the conversational discourse between residents, this same analytical

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Saunders et al. 11

tool can easily be applied to the conversations between resident and staff members. The

identification of conversational objects allows for the analysis of coherent conversations, as

well as of misunderstandings, as seen in Example 2, with Bob and John’s conversation about

the staff member. Bob is doing his best to have a friendly conversation with John about his

memories of himself at a younger age. John in turn is trying to make sense of what John was

saying. This misunderstanding reveals much about how persons with dementia communicate

despite cognitive impairments. That is, they communicate using indefinite linguistic reference

and use alignment of social identities (old self versus young self) thus revealing how social

relationships are constructed in this setting. That is, there may be misunderstandings, and

yet the relationship still perseveres as relationships do among non-diagnosed people who

experience misunderstandings in conversation.

While staff communication was not itself examined here, it was inevitable that it would

appear as part of the communicative interaction in the long-term care setting (Small, Gutman,

Makela, & Hillhouse, 2003). Between staff members and residents, conversational objects

motivate conversation and smooth interaction. In Example 1, the conversational object

starts out as a tape recorder. However, as the conversation ensued Laura, another staff

member, interprets the conversational object to be something else. While it is not clear

whether re-framing is a conscious move on Laura’s part, there was some resolution to the

issue when Anna accepted the glass of water. Vasse, Vernooij-Dassen, Spijker, Rikkert, and

Koopmans (2010) reviewed the literature on staff interventions designed to improve

communication strategies among residents in long-term care facilities. While the meta-

analysis found no overall effects, several of the single-task session interventions with

residents (e.g., life review) and one-on-one tasks embedded in activities of daily living

showed improved communication. Future studies of intervention should include

information for staff members about how persons with dementia use language to construct

their social relationships. In addition, such training should emphasize how the role of the staff

members themselves influences social interaction among residents and how such influence can

be improved further.

Conclusion

While research on the subjective experience of dementia is a growing field (Pearce et al.,

2002; Sabat, 2001; Woods, 2001; Clare, Rowlands, Bruce, Surr & Downs, 2008), additional

research is necessary to understand how the person diagnosed copes with the difficulties (the

realities of their) everyday life. The Friendship Study used both ethnographic and

neuropsychological assessments to explore communication and social relationships among

persons with dementia in the long-term care setting, as well as to examine individual views of

friendship (see the companion article be de Medeiros et al. in this issue), all while keeping the

perspective and the experience of the persons with dementia as a focus of this research.

Using discourse analysis, the conversational examples in this paper illustrate how persons

with dementia use specific linguistic behaviors to construct and maintain relationships with

their fellow residents. These conversational interactions are evidence of how these

individuals construct their own social identities and, in so doing, their social relationships.

Using language, these individuals align themselves with each other to form social bonds at

the conversational level. At the same time, using language in their daily conversations, they

indexically construct social meaning and social relationships with their table-mates. The

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

12 Dementia 0(0)

individuals observed herein are very capable of forming and maintaining friendships, or

pleasant social relationships despite their cognitive or physical impairments. Future

studies will examine interventional strategies with staff and family caregivers to improve

social interaction in long-term care settings.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association (NIRG-08-91764).

Many thanks are given to Philip A. Saunders for thoroughly proof-reading this and many

other manuscripts.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Notes

1. Transcription conventions are modified from Du Bois (1991).

2. Anaphora is an instance of one expression referring to another. A cataphoric reference is used to

describe an expression that co-refers with a later expression in the discourse.

3. ‘Today’ in this context may be analyzed as a noun or an adverb depending on the completion of

the sentence. Assuming the rest of the sentence was ‘Today I would like to have another

appointment’, then it would be an adverb modifying time.

References

Astell, A. J., & Ellis, M. P. (2006). The social function of limitation in severe dementia. Infant and Child

Development, 15, 311–319.

Baldry, A., & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis: A multimodal toolkit

and coursebook with associated on-line course. London: Equinox Publishing.

Black, B. S., Kass, N. E., Fogarty, L. A., & Rabins, P. V. (2007). Informed consent for dementia

research: The study enrollment encounter. IRB: Ethics and Human Research, 29(4), 7–14.

Brawley, E. (2006) Design Innovations for Aging and Alzheimer’s: Creating Caring Environments. New

York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Briller and Calkins (2000) Conceptualizing care settings as home, resort or hospital. Alzheimer’s Care

Quarterly, 1(1), 17–23.

Chen, Y., Ryden, M., Feldt, K., & Savik, K. (2000). The relationship between social interaction and

characteristics of aggressive, cognitively impaired nursing home residents. American Journal of

Alzheimer’s Disease, 15, 10–17.

Clare, L. (2002). We’ll fight it as long as we can: Coping with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging

and Mental Health, 6, 139–148.

Clare, L. (2003). Managing threats to self: The construction of awareness in early-stage Alzheimer’s

disease. Social Science and Medicine, 57, 1017–1029.

Clare, L., Goater, T., & Woods, B. (2006). Illness representations in early-stage dementia:

A preliminary investigation. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21, 761–767.

Clare, L., Rowlands, J., Bruce, E., Surr, C., & Downs, M. (2008). The experience of living with

dementia in residential care: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Gerontologist, 48,

711–720.

Clark, L. W. (1995). Intervention for persons with Alzheimer’s disease: Strategies for maintaining and

enhancing communicative success. Topics in Language Disorders, 15, 47–66.

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Saunders et al. 13

Cohen-Mansfield, J., & Marx, M. S. (1992). The social network of the agitated nursing home resident.

Research on Aging, 14, 110–123.

Cotrell, V., & Schulz, R. (1993). The perspective of the patient with Alzheimer’s disease: A neglected

dimension of dementia research. The Gerontologist, 33, 205–211.

Davis, S., Byers, S., Nay, R., & Koch, S. (2009). Guiding design of dementia friendly environments in

residential care settings: Considering the living experiences. Dementia, 8, 185–203.

Diaz Moore, K. (1999). Dissonance in the dining room: A study of social interaction in a special care

unit. Qualitative Health Research, 9, 133–155.

Downs, M. (1997). The emergence of the person in dementia research. Ageing and Society, 17, 597–607.

Du Bois, J. W. (1991). Transcription design principles for spoken discourse research. Pragmatics, 1,

71– 106.

Dunn, L. A., Rout, U., Carson, J., & Ritter, S. A. (1994). Occupational stress amongst care staff

working in nursing homes: An empirical investigation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 3, 177–183.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state: A practical method for

grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. New York: Harper & Row.

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gurland, B., Toner, J., Wilder, D., Chen, J., & Lantigua, R. (1994). Impairment of communication and

adaptive functioning in community-residing elderly with advanced dementia. Alzheimer Disease and

Associated Disorders, 8, 230–241.

Hamilton, H. (1994). Conversations with an Alzheimer’s patient: An interactional examination of

questions and responses. New York: Cambridge.

Harman, G., & Clare, L. (2006). Illness representations and lived experience in early-stage dementia.

Qualitative Health Research, 16, 484–502.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Harris, P. B. (Ed.) (2002). The person with Alzheimer’s disease: Pathways to understanding the

experience. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hughes, J., Louw, S. J., & Sabat, S. (Eds.) (2006). Dementia: Mind, meaning, and the person. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Iedema, R. (2003). Multimodality, resemioticization: Extending the analysis of discourse as a

multisemiotic practice. Visual Communication, 2, 29–57.

Kitwood, T. (1993). Towards a theory of dementia care: The interpersonal process. Aging and Society,

13, 51–67.

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia Reconsidered: The person comes first. Rethinking Aging. Buckingham:

Open University Press.

Kitwood, T., & Benson, S. (1995). The new culture of dementia care. London: Hawker Publications.

Kitwood, T., & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being.

Ageing Society, 12, 269–287.

Kutner, N. G., Brown, P. J., Stavisky, R. C., Clark, W. S., & Green, R. C. (2000). ‘‘Friendship’’

interactions and expression of agitation among residents of a dementia care unit: Six-month

observational data. Research on Aging, 22, 188–205.

Keady, J., & Nolan, M. (1995). IMMEL: Assessing coping responses in the early stages of dementia.

British Journal of Nursing, 4, 309–314.

Keady, J., Nolan, M. R., & Gilliard, J. (1995). Listen to the voices of experience. Journal of Dementia

Care, 3(May–June), 15–17.

Kontos, P. C. (2006). Embodied selfhood: An ethnographic exploration of Alzheimer’s disease.

In A. Leibing, & L. Cohen (Eds.), Thinking about dementia: Culture, loss, and the anthropology

of senility (pp. 195–217). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Leibing, A., & Cohen, L. (Eds.) (2006). Thinking about dementia: Culture, loss, and the anthropology of

senility. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics. Oxford: Cambridge University Press.

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

14 Dementia 0(0)

Lyons, J. (1977). Deixis, space and time. Semantics, 2, 636–724.

Mittelman, M. S., Ferris, S. H., & Steinberg, G. (1993). An intervention that delays institutionalization

of Alzheimer’s disease patients: treatment of spouse-caregivers. The Gerontologist, 33, 730–740.

Mobily, P. R., Maas, M. L., Buckwalter, K. C., & Kelley, L. S. (1992). Staff stress on an Alzheimer’s

unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing in Mental Health Services, 30, 25–31.

Orange, J. B. (1991). Perspectives of family members regarding communication changes.

In R. Lubinski (Ed.), Dementia and Communication (pp. 168–186). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby.

Orange, J. B., & Colton-Hudson, A. (1998). Enhancing communication in dementia of the Alzheimer’s

type. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 14(2), 56–75.

Pearce, A., Clare, L., & Pistrang, N. (2002). Managing sense of self: Coping in the early stages of

Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 1, 173–192.

Peirce, C. S. (1932). Division of signs. In Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Phinney, A. (2002). Living with the symptoms. In P. B. Harris (Ed.), The person with Alzheimer’s

disease (pp. 49–76). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ramanathan, V. (1997). Alzheimer Discourse: Some Sociolinguistic Dimensions. Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Richter, J. M., Roberto, K., & Bottenberg, D. J. (1995). Communicating with persons with

Alzheimer’s disease: Experiences of family and formal caregivers. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing,

9, 279–285.

Sabat, S. R. (2001). The experience of Alzheimer’s disease: Life through a tangled veil. Oxford:

Blackwell.

Sabat, S. R., & Harré, R. (1992). The construction and deconstruction of self in Alzheimer’s disease.

Aging and Society, 12, 443–461.

Saunders, P. A. (1998a). ‘‘You’re out of your mind!’’ An analysis of humor as a face saving strategy for

patients and clinicians during neuropsychological examinations. Health Communication, 10,

357–372.

Saunders, P. A. (1998b). ‘‘My brain’s on strike’’: The construction of identity through memory

accounts by dementia patients. Research on Aging, 20, 65–90.

Schulz, R., & O’Brien, A. T. (1994). Alzheimer’s disease caregiving: An overview. Seminars in Speech

and Language, 15, 185–194.

Small, J. A., Gutman, G., Makela, S., & Hillhouse, B. (2003). Effectiveness of communication

strategies used by caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease during activities of daily living.

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46, 353–367.

Van Dijkhuizen, M., Clare, L., & Pearce, A. (2006). Striving for connection: Appraisal and coping

among women with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 5(1), 73–94.

Vasse, E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Spijker, A., Rikkert, M. O., & Koopmans, R. (2010). A systematic

review of communication strategies for people with dementia in residential and nursing homes.

International Psychogeriatrics, 22(02), 189.

Williamson, G. M., & Schulz, R. (1993). Coping with specific stressors in Alzheimer’s disease

caregiving. The Gerontologist, 33, 747–755.

Wood, K. A., Cooper, J. A., Richardson, K., & Forbes, A. (1992). Affective behaviour and success of

EMI community home placement. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 7, 351–356.

Woods, R. T. (2001). Discovering the person with Alzheimer’s disease: Cognitive, emotional, and

behavioral aspects. Aging and Mental Health, 5, 7–S16.

Wright, L. W. (1993). Alzheimer’s Disease and Marriage. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Pamela A. Saunders, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Neurology and

Psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine. Her research focuses on the

identity, and the preserved, communicative abilities of persons with dementia. In addition,

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

XML Template (2011) [3.11.2011–3:08pm] [1–15]

K:/DEM/DEM 421187.3d (DEM) [PREPRINTER stage]

Saunders et al. 15

she teaches medical students how to communicate in clinical settings. She is the author of

multiple articles on language, communication, and dementia as well as in the arena of

medical education.

Kate de Medeiros, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Gerontology in the Department of

Sociology and Gerontology, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. Her research focuses

broadly on the construction of selfhood in old age and includes work on friendships and

self expression/performance through autobiographical writing for a variety of older

populations. She has published work on the complementary self in old age, narrative

explorations of selfhood, neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia, and the meaning of

suffering.

Patrick Doyle, MA, is a doctoral candidate in Gerontology at the University of Maryland,

Baltimore County. His research has focused on how caregiving practices, physical

environments, and social interactions influence the lived experience of people with

dementia residing in long-term care settings. In his dissertation research, he is examining

how a person-centered model of care is interpreted and applied by various stakeholders

within a dementia-specific long-term care setting.

Amanda Mosby graduated from Indiana University with a master’s degree in social and

cognitive psychology. She has directed a variety of research studies that have focused on

sociological, behavioral, and public health issues including memory performance in older

adults and the concept of generativity in childless older women. She is currently a research

associate at the University of Maryland Baltimore County in the Department of Sociology

and Anthropology.

Downloaded from dem.sagepub.com at Miami University Libraries on October 5, 2016

View publication stats

You might also like

- Savage Worlds MLP EditionDocument66 pagesSavage Worlds MLP EditionCarsten_Curren_7854100% (8)

- Introvert Extrovert QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesIntrovert Extrovert QuestionnaireJustin Oliver Hautea67% (3)

- Maiorescu 2017Document25 pagesMaiorescu 2017Ligia-Elena StroeNo ratings yet

- Comparision of Banking System of Us, Europe, India-1Document36 pagesComparision of Banking System of Us, Europe, India-1Rashmeet Kaur100% (2)

- Purpose of Summons in Action in Rem and Quasi in RemDocument4 pagesPurpose of Summons in Action in Rem and Quasi in Remjane100% (2)

- Miller 2014Document17 pagesMiller 2014dantealtighieriNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis PaperDocument24 pagesFinal Thesis PaperJessa D. SabudNo ratings yet

- Tomenyetal.2017 RIDD PreprintDocument35 pagesTomenyetal.2017 RIDD Preprintsanskriti gautamNo ratings yet

- AAC Interventions For Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders - State of The Science and Future Research DirectionsDocument13 pagesAAC Interventions For Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders - State of The Science and Future Research DirectionsLiamariasabauNo ratings yet

- Public Display of AffectionDocument2 pagesPublic Display of AffectionMicca MitraNo ratings yet

- Div Class Title Socioemotional Profiles of Autism Spectrum Disorders Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Disinhibited and Reactive Attachment Disorders a Symptom Comparison and Network Approach DiDocument10 pagesDiv Class Title Socioemotional Profiles of Autism Spectrum Disorders Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Disinhibited and Reactive Attachment Disorders a Symptom Comparison and Network Approach DiArnau Miquel CosNo ratings yet

- Everyday Conversation in Dementia A Review of The Literature To Inform Research and PracticeDocument15 pagesEveryday Conversation in Dementia A Review of The Literature To Inform Research and Practicexyang105No ratings yet

- Dissociation, Dissociative Disorders, and PTSD: January 2015Document17 pagesDissociation, Dissociative Disorders, and PTSD: January 2015Jorge LusagaNo ratings yet

- AJSLP BradyDocument14 pagesAJSLP BradygiselleprovencioNo ratings yet

- Morgan - Students' Perceptions of The Effect (AAM) 2016Document39 pagesMorgan - Students' Perceptions of The Effect (AAM) 2016Tarun SoniNo ratings yet

- Fears Article CCR 2012 April Dwyer DavidsonDocument11 pagesFears Article CCR 2012 April Dwyer DavidsonaachecheutautautaNo ratings yet

- Channels of Computer-Mediated Communication and Satisfaction in Long-Distance RelationshipsDocument17 pagesChannels of Computer-Mediated Communication and Satisfaction in Long-Distance RelationshipsgabbymacaNo ratings yet

- Wrzus Etal2017friendship AdulthoodDocument17 pagesWrzus Etal2017friendship AdulthoodRheivita Mutiara FawzianNo ratings yet

- ContentserverDocument18 pagesContentserverapi-406956380No ratings yet

- The Benefit of Contact For Prejudice-Prone Individuals: The Type of Stigmatized Outgroup MattersDocument14 pagesThe Benefit of Contact For Prejudice-Prone Individuals: The Type of Stigmatized Outgroup MattersSiti SurtiNo ratings yet

- Personality and Individual Di FferencesDocument6 pagesPersonality and Individual Di FferencesJefri ansyahNo ratings yet

- This Is Me: Evaluation of A Boardgame To Promote Social Engagement, Wellbeing and Agency in People With Dementia Through Mindful Life-StorytellingDocument23 pagesThis Is Me: Evaluation of A Boardgame To Promote Social Engagement, Wellbeing and Agency in People With Dementia Through Mindful Life-StorytellingNatalia Francisca ValdésNo ratings yet

- Marquardt Et Al 2014 Impact of The Design of The Built Environment On People With Dementia An Evidence Based ReviewDocument31 pagesMarquardt Et Al 2014 Impact of The Design of The Built Environment On People With Dementia An Evidence Based Reviewyfive soneNo ratings yet

- J DENT RES-2015-Schwendicke-10-8Document9 pagesJ DENT RES-2015-Schwendicke-10-8Tahir AliNo ratings yet

- Willingness To Communicate in A Second Language THDocument21 pagesWillingness To Communicate in A Second Language THBaihaqi Zakaria MuslimNo ratings yet

- Is Public Speaking Really More Feared Than Death?: Communication Research Reports April 2012Document11 pagesIs Public Speaking Really More Feared Than Death?: Communication Research Reports April 2012Gilang NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Navigating Thin' Dating Markets: Mid-Life Repartnering in The Era of Dating Apps and WebsitesDocument17 pagesNavigating Thin' Dating Markets: Mid-Life Repartnering in The Era of Dating Apps and WebsitescutkilerNo ratings yet

- 2020-InfluenceTraumaSymptomsonAlliance JCD1 PDFDocument13 pages2020-InfluenceTraumaSymptomsonAlliance JCD1 PDFIsaac AkakyinsimiraNo ratings yet

- When Online Meets Offline The Effect of Modality Switching On Relational CommunicationDocument25 pagesWhen Online Meets Offline The Effect of Modality Switching On Relational CommunicationAbdul WahabNo ratings yet

- Edwards Bybee Frost Harvey Navarro 2017Document24 pagesEdwards Bybee Frost Harvey Navarro 2017polandpoplawskaNo ratings yet

- Article - Evaluating The Efficacy of Drama Therapy in Teaching Social Skills To Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument20 pagesArticle - Evaluating The Efficacy of Drama Therapy in Teaching Social Skills To Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDespina Kalaitzidou100% (3)

- Sibling Relationship and Friendship in Adolescents With AutismDocument10 pagesSibling Relationship and Friendship in Adolescents With AutismNobodyNo ratings yet

- A Multi-Study Examination of Attachment and Implicit Theories of Relationships in Ghosting ExperiencesDocument24 pagesA Multi-Study Examination of Attachment and Implicit Theories of Relationships in Ghosting ExperiencesAquina Case SaymanNo ratings yet

- Love OnlineDocument14 pagesLove Onlineferrerkale13No ratings yet

- Intergroup Contact, Social Dominance and Environmental Concern: A Test of The Cognitive-Liberalization HypothesisDocument64 pagesIntergroup Contact, Social Dominance and Environmental Concern: A Test of The Cognitive-Liberalization HypothesisAbdülkadir IrmakNo ratings yet

- 3 - Acquiescence-Response-Styles - A-Multilevel-Model-Exp - 2017 - Personality-and-InDocument5 pages3 - Acquiescence-Response-Styles - A-Multilevel-Model-Exp - 2017 - Personality-and-InbelenNo ratings yet

- The Best PDF Ever Download It NowDocument7 pagesThe Best PDF Ever Download It Nowchiquinho.gaviao231No ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography SampleDocument9 pagesAnnotated Bibliography SampleIan Paul Hurboda DaugNo ratings yet

- Wan Muelleretal - gpsdementiaCareAcademia-Industryperspective ToCHI2016Document37 pagesWan Muelleretal - gpsdementiaCareAcademia-Industryperspective ToCHI2016Mharits FadhillaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Outline On Down SyndromeDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Outline On Down Syndromeegw4qvw3100% (1)

- Computers in Human Behavior: Brendan Dempsey, Kathy Looney, Roisin Mcnamara, Sarah Michalek, Eilis HennessyDocument9 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Brendan Dempsey, Kathy Looney, Roisin Mcnamara, Sarah Michalek, Eilis HennessyFulaneto AltoNo ratings yet

- Brand Loewenstein Spiegel Dispelling Myths DIDTreatment 2014Document23 pagesBrand Loewenstein Spiegel Dispelling Myths DIDTreatment 2014Inna RiegoNo ratings yet

- The Art of Breaking Up - Ending Romantic RelationshipsDocument45 pagesThe Art of Breaking Up - Ending Romantic Relationshipspaul tNo ratings yet

- Article 5Document24 pagesArticle 5syamimiNo ratings yet

- Can Digital Technology Enhance Social Connectedness Among Older Adults? A Feasibility StudyDocument24 pagesCan Digital Technology Enhance Social Connectedness Among Older Adults? A Feasibility Studydena dgNo ratings yet

- Disclosure of Stuttering and Quality of Life in People Who StutteDocument11 pagesDisclosure of Stuttering and Quality of Life in People Who Stuttephelie2008No ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-259529340No ratings yet

- New Nomenclature DementiaDocument7 pagesNew Nomenclature DementiaFernando lazzarettiNo ratings yet

- DEMTEC Health Care ProfessionalsDocument28 pagesDEMTEC Health Care ProfessionalsrajasinguNo ratings yet

- Decision Making Styles East and West Is It Time ToDocument9 pagesDecision Making Styles East and West Is It Time ToSharrme ChandranNo ratings yet

- 1.) Fear of Public Speaking - Perception of College Students and Correlates - ScienceDirectDocument6 pages1.) Fear of Public Speaking - Perception of College Students and Correlates - ScienceDirectwakinn lezgoNo ratings yet

- 1Document134 pages1ghizlane berradaNo ratings yet

- Loneliness Being AloneDocument17 pagesLoneliness Being AloneAsri PutriNo ratings yet

- DospertDocument12 pagesDospertAndreea LixandruNo ratings yet

- Comm Research Final PaperDocument19 pagesComm Research Final Paperapi-528626923No ratings yet

- Do You Have Anything To Hide Infidelity-Related BeDocument33 pagesDo You Have Anything To Hide Infidelity-Related BeDewwii AmbarwatiiNo ratings yet

- 2022 Duker - ReviewDocument19 pages2022 Duker - Reviewfabian.balazs.93No ratings yet

- Different Types of Internet Use, Depression, and Social Anxiety: The Role of Perceived Friendship QualityDocument16 pagesDifferent Types of Internet Use, Depression, and Social Anxiety: The Role of Perceived Friendship QualityTom ArrolloNo ratings yet

- Research On NarcissismDocument46 pagesResearch On NarcissismBen ApawNo ratings yet

- Trans and Family Therapy Edwards2018Document17 pagesTrans and Family Therapy Edwards2018Francisca Nilsson RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Lanzi Burshnic Bourgeois 2017Document15 pagesLanzi Burshnic Bourgeois 2017DivyaChettyNo ratings yet

- Workplace Relationships, Stress, and Verbal Rumination in OrganizationsDocument12 pagesWorkplace Relationships, Stress, and Verbal Rumination in OrganizationsHany A AzizNo ratings yet

- Mrug 09Document10 pagesMrug 09Savio RebelloNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Dementia and Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting conversationsFrom EverandFast Facts: Dementia and Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting conversationsNo ratings yet

- A Corpus Based Analysis of William BlakeDocument20 pagesA Corpus Based Analysis of William BlakeTamta NagervadzeNo ratings yet

- WS ARTIST Final Conference CUN Siol EilksDocument35 pagesWS ARTIST Final Conference CUN Siol EilksTamta NagervadzeNo ratings yet

- Speaking and Listening Skills DevelopmentDocument37 pagesSpeaking and Listening Skills DevelopmentTamta NagervadzeNo ratings yet

- Yesterday? I Walk To SchoolDocument6 pagesYesterday? I Walk To SchoolTamta NagervadzeNo ratings yet

- The Application of Translation Strategies and Predicate Transformations in Teaching Written TranslationDocument13 pagesThe Application of Translation Strategies and Predicate Transformations in Teaching Written TranslationTamta NagervadzeNo ratings yet

- A Critical Discourse Analysis of The Power RelatioDocument6 pagesA Critical Discourse Analysis of The Power RelatioTamta NagervadzeNo ratings yet

- Book Review by Azhar Kaz MiDocument3 pagesBook Review by Azhar Kaz Miappu kundaNo ratings yet

- Petition For Change of NameDocument44 pagesPetition For Change of NameLenNo ratings yet

- Case Study 4: Brothers MowersDocument2 pagesCase Study 4: Brothers MowersRayan HafeezNo ratings yet

- unit5-MB 0001Document12 pagesunit5-MB 0001yogaknNo ratings yet

- Somebody To LoveDocument3 pagesSomebody To LoveIksan PutraNo ratings yet

- Circulatory SystemDocument5 pagesCirculatory SystemMissDyYournurse100% (1)

- Universal Network Solutions IncDocument15 pagesUniversal Network Solutions IncChandu NsaNo ratings yet

- UOI V Indian Navy Civilian Design Officers Association & AnrDocument6 pagesUOI V Indian Navy Civilian Design Officers Association & Anrkhyati vermaNo ratings yet

- HRM WordDocument7 pagesHRM WordShaishav BhesaniaNo ratings yet

- IC5 L1 WQ U15to16 PDFDocument2 pagesIC5 L1 WQ U15to16 PDFRichie Ballyears100% (1)

- How To Use ArticlesDocument7 pagesHow To Use Articlescrazy about readingNo ratings yet

- Chemistry CrosswordDocument1 pageChemistry CrosswordHanifan Al-Ghifari W.No ratings yet

- WFDDocument97 pagesWFDajay WaliaNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlansDocument7 pagesLesson Plansapi-316237434100% (1)

- FPEBb6 Hadji Nabel FPE MidtermDocument5 pagesFPEBb6 Hadji Nabel FPE MidtermNadhif Radiamoda Hadji NabelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Solution 1Document4 pagesChapter 2 Solution 1Pragya PandeyNo ratings yet

- Action Plan - Brigada Eskwela 2022Document1 pageAction Plan - Brigada Eskwela 2022Anna Lou R. retubaNo ratings yet

- Mapping Toolbox GuideDocument1,710 pagesMapping Toolbox GuideAaron RampersadNo ratings yet

- Fantastics English Monday Letter Writing Powerpoint 41973Document17 pagesFantastics English Monday Letter Writing Powerpoint 41973Aryan KyathamNo ratings yet

- Fulltext 01Document54 pagesFulltext 01Shafayet UddinNo ratings yet

- Daily Painting and Observations On Art, Nature and Life, by Stefan BaumannDocument122 pagesDaily Painting and Observations On Art, Nature and Life, by Stefan BaumannStefan BaumannNo ratings yet

- Lecture Planner - Mathematics - LAKSHYA JEE 2022 PLANNER - MathematicsDocument5 pagesLecture Planner - Mathematics - LAKSHYA JEE 2022 PLANNER - MathematicsprekshaNo ratings yet

- UAS Pre ExerciseDocument2 pagesUAS Pre Exerciserain maker100% (2)

- English PunctuationDocument157 pagesEnglish Punctuationayman.barghash9635No ratings yet

- Secretary of Justice v. LantionDocument53 pagesSecretary of Justice v. LantionKristinaCuetoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 Activity CrashingDocument17 pagesLesson 4 Activity CrashingMuhammad Syahir BadruddinNo ratings yet